Abstract

Several lines of evidence indicate that macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α) modulates the proliferation of hematopoietic progenitor cells, depending on their maturational stages. To clarify the mechanisms for the modulation of hematopoiesis by this chemokine, we examined the expression of a receptor for MIP-1α, CCR1, on bone marrow cells of normal individuals using a specific antibody and explored the effects of MIP-1α on in vitro erythropoiesis driven by stem cell factor (SCF) and erythropoietin (Epo). CCR1 was expressed on glycophorin A-positive erythroblasts in addition to lymphocytes and granulocytes. CCR1+ cells, isolated from bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMNCs) using a cell sorter, comprised virtually all erythroid progenitor cells in the BMMNCs. Moreover, MIP-1α inhibited, in a dose-dependent manner, colony formation by burst-forming unit-erythroid (BFU-E), but not by colony forming unit-erythroid (CFU-E), in a methylcellulose culture of purified human CD34+ bone marrow cells. Although reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) showed the presence of CCR1, CCR4, and CCR5 transcripts in CD34+ cells in BM, anti-CCR1 antibodies significantly abrogated the inhibitory effects of MIP-1α on BFU-E formation both in a methylcellulose culture and in a single cell proliferation assay of purified CD34+ cells. Although the contribution of CCR4 or CCR5 cannot be completely excluded, these results suggest that MIP-1α–mediated suppression of the proliferation of immature, but not mature erythroid progenitor cells, is largely mediated by CCR1 expressed on these progenitor cells.

CHEMOKINES ARE A growing family of cytokines with the ability to attract and activate various types of leukocytes. Chemokines have four cysteines at well-conserved positions and can be subdivided into two subfamilies, depending on whether the first pair of cysteines is separated by one amino acid (C-X-C) or adjacent (C-C).1 A C-C chemokine, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α, was originally identified as the gene expressed in activated T cells.2-4 Subsequent studies demonstrated that a wide variety of cells can produce MIP-α in response to various stimuli.3,5,6 MIP-α in vitro chemoattracts monocytes, CD8+ T lymphocytes and activates eosinophils, basophils and mast cells,1 7-9 suggesting its potential role in inflammation.

The crucial role of MIP-α in inflammation has been substantiated by the observations that neutralizing antibodies to MIP-α alleviated the pathological changes in several inflammatory models such as Schistosoma manoni infection, endotoxemia, bleomycin-induced lung injury, and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis.10-13 Moreover, gene targeting of MIP-α impaired the response to Coxsackie and influenza virus infection, suggesting its involvement in virus-induced inflammation.14 Furthermore, a major coreceptor for macrophage-tropic human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has been identified as CCR5, a receptor for C-C chemokines such as MIP-α , MIP-1β, and RANTES.15-18 These observations indicate the potential role of MIP-α in various types of inflammation including virus infection.

In addition to its roles in inflammation, accumulating evidence indicates that MIP-α also exhibits effects on hematopoietic progenitor cells.19-28 Systemic injection of MIP-α mobilizes bone marrow (BM) progenitor cells rapidly into peripheral blood.22 In vitro proliferation of hematopoietic progenitor cells is affected by MIP-α in a complicated way.29 Broxmeyer et al20 proposed that MIP-α enhances the growth of mature myeloid progenitors, while it has direct suppressing activity for immature ones. The effects of MIP-α were proposed to be mediated by enhanced phosphocholine metabolism or protein kinase A activation.30 31 However, the identity of the chemokine receptor(s) engaged in MIP-α –mediated hematopoietic progenitor cell proliferation, remains to be established.

Five homologous G-protein-coupled receptors for C-C chemokines designated CCR, have been identified.32-40 Among these five receptors, the transfection of CCR1, CCR4, and CCR5 cDNA confers responsiveness to MIP-α.32-34,37-40 Our previous immunofluorescence analysis using specific antibodies to CCR1 demonstrated that CCR1 expression is restricted to monocytes, CD4+ T lymphocytes, CD8+ T lymphocytes, CD16+ natural killer cells in peripheral blood, as well as CD34+ cells in BM and cord blood.41 Here, we demonstrate that mature erythroblasts and erythroid progenitor cells in BM also express CCR1. This led us to detect an in vitro effect of MIP-α on the proliferation of erythroid progenitor cells and the involvement of CCR1 in this activity of MIP-α.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.Human recombinant MIP-α and human recombinant erythropoietin (Epo) were generously provided by Ohtsuka Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd (Tokushima, Japan) and Chugai Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd (Tokyo, Japan), respectively. Recombinant human stem cell factor (SCF) and interleukin (IL)-3 were kind gifts from Kirin Brewery Company (Tokyo, Japan). Endotoxin was not detected in these preparations using a Toxicolor assay (Seikagaku-Kogyo, Tokyo, Japan). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated monoclonal antibody (MoAb) to CD34 and phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled MoAb to human glycophorin A were obtained from DAKO A/S (Glostrup, Denmark) and Pharmingen (San Diego, CA), respectively. An FITC-conjugated goat antirabbit IgG was purchased from Dainippon Pharmaceutical Co Ltd (Osaka, Japan). Specific polyclonal antibodies to CCR1 were prepared by immunizing rabbits with recombinant glutathione-S–transferase (GST) fused with the NH2-terminal portion of CCR1. The antibodies did not show any cross-reactivities against NH2-terminal portion of other chemokine receptors as described previously.41

Cell preparation procedures.Human BM was aspirated from the posterior iliac crest of normal healthy volunteers with their informed consent. Nucleated cells were obtained from BM by disrupting red blood cells using 0.83% ammonium chloride. Thereafter, BM mononuclear cells (BMMNCs) were recovered by a density-separation using Ficoll-Hypaque (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO). CD34+ cells were further isolated from BMMNCs stained with FITC-labeled anti-CD34 MoAb by using an EPICS ELITE cell sorter (Coulter Electronics, Hialeah, FL) as previously described.42

Immunofluorescence analysis.Immunofluorescence analysis was performed using an EPICS ELITE cell sorter as previously described.41 To analyze CCR1 expression, 5 to 10 × 105 cells were first incubated in a washing buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS], pH 7.4, 2.5% fetal bovine serum [FBS], 0.1% sodium azide) containing 5% normal goat serum and then treated with (Fab')2 fragments of rabbit anti-CCR1 receptor or anti-GST antibodies at a final concentration of 50 μg/mL. Subsequently, the cells were stained with a 400-fold diluted goat antirabbit IgG antibody conjugated with FITC. In two-color immunofluorescence analyses, the cells were simultaneously stained directly with the optimal dilution of PE-labeled MoAb to glycophorin A, to evaluate the expression of CCR1 on glycophorin A-positive population. In some experiments, anti-CCR1 antibody-stained cells present in BM nucleated cells were sorted based on the immunofluorescence intensity, for subsequent morphological evaluation on May-Grünwald-Giemsa stained preparations or a methylcellulose culture. All incubations were performed for 30 minutes on ice followed by two washes.

Methylcellulose culture of cells.Fifty thousand CCR1+ or CCR1- cells, or 1,000 CD34+ cells were plated into 12-well tissue plates in quadruplicate in 1 mL of Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM) containing 0.9% methylcellulose (Shinetsu Chemical Co, Tokyo, Japan), 30% heat-inactivated FBS, 1% deionized bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma Chemical) with various combinations of the indicated concentrations of Epo (2 U/mL), SCF (50 ng/mL), MIP-α, anti-CCR1 IgG, and control rabbit IgG and were placed in a humidified incubator at 37°C in 5% CO2. The purity of the cell populations to be cultured was higher than 98% as determined by an immunofluorescence analysis. The number of colony-forming unit-erythroid (CFU-E)–derived colonies consisting of 8 to 49 hemoglobin-containing cells was determined at day 7, while that of burst-forming unit-erythroid (BFU-E)–derived colonies consisting of more than 500 hemoglobin-containing cells was determined at day 14 of the cell culture using an inverted microscope.

Single cell colony assay.A single cell colony assay was performed as previously described.42 The isolated CD34+ cells were suspended in IMDM supplemented with 0.9% methylcellulose, 30% FBS, 1% BSA containing the various combinations of Epo, SCF, MIP-α, and anti-CCR1 antibodies. A total of 100 μL of cell suspensions was dispensed into each well of 96-multiwell plates (Nunc Inc, Roskilde, Denmark) at a cell concentration of one cell per well and were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. The numbers of wells in which colonies of BFU-E appeared were determined under an inverted microscope at day 14 of the incubation. The frequency was determined by dividing the number of wells with a colony by the total number.

Detection of C-C chemokine receptor transcripts by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).CD34+ cells from normal BM were collected using a cell sorter and the purity of the resultant cell population was higher than 98%. Using RNAzolTM B (Biotex Laboratories Inc, Houston, TX), total RNAs were extracted from 1.4 × 104 CD34+ cells according to the manufacturer's instructions. First-strand cDNA was synthesized in a 25-μL reaction volume using an RT-PCR kit (from Takara Shuzo, Kyoto, Japan) with random primers according to the manufacturer's instructions. Thereafter, cDNA was amplified for 40 cycles consisting of 94°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 1.5 minutes with a set of oligomers, which will amplify specifically the NH2-terminal portion of each C-C chemokine receptor (Table 1). After being amplified, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products were fractionated on a 5% polyacrylamide gel and were visualized by ethidium bromide staining. In some experiments, the nucleotide sequence of the resultant fragments was determined directly by a chain terminating method.

Statistical analysis.The data were analyzed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by multiple comparison by Fisher's method.

RESULTS

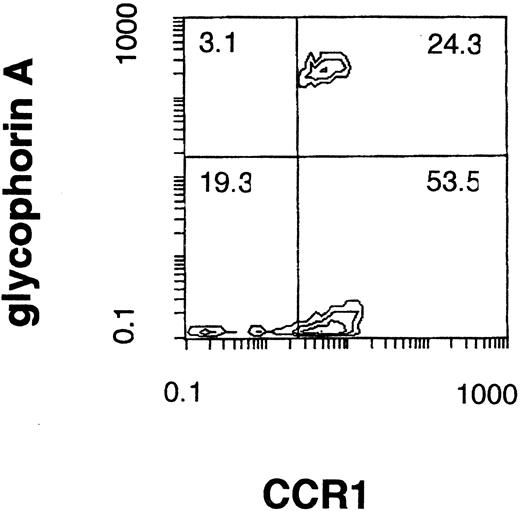

Morphology and phenotype of CCR1+ cells in normal BM.We previously observed that most of CD34+ BMMNCs expressed uniformly a C-C chemokine receptor, CCR1.41 Hence, we morphologically examined CCR1+ cells in BM cells after collecting positive cells using a cell sorter. Consistent with our previous observation, CCR1+ cells comprised lymphocytes and monocytes. Mature granulocytes, such as metamyleocytes, band, segmented granulocytes, barely expressed CCR1 (Table 2). In addition, unexpectedly, erythroblasts and plasma cells were contained in CCR1+ cells, in addition to immature granulocytes, such as blast cells and promyelocytes. Two-color immunofluorescence analysis further showed that most of the glycophorin A positive cells were stained with anti-CCR1 antibodies (Fig 1). These results indicate that most of the mature erythroblasts express CCR1.

CCR1 expression on glycophorin A positive BM nucleated cells. The normal BM nucleated cells were analyzed using a two-color immunofluorescence as described in Materials and Methods. The figure in each quadrant represents the percentage of cells.

CCR1 expression on glycophorin A positive BM nucleated cells. The normal BM nucleated cells were analyzed using a two-color immunofluorescence as described in Materials and Methods. The figure in each quadrant represents the percentage of cells.

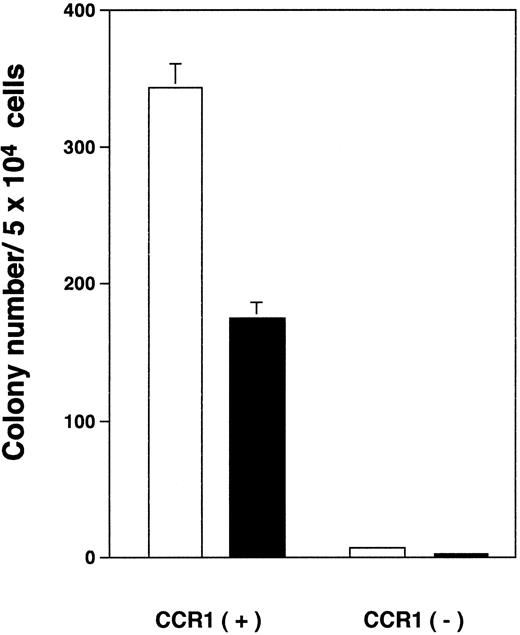

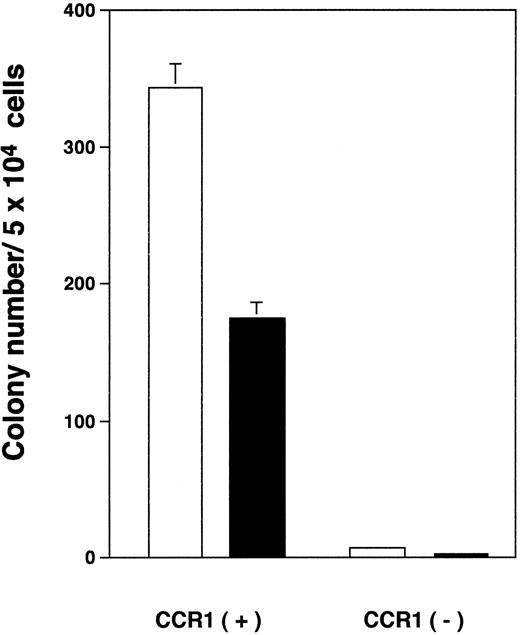

CFU-E– and BFU-E–derived colony formation from CCR1+ BM cells.To determine whether CCR1 is expressed by erythroid progenitor cells, we examined purified CCR1+ cells in BM for the presence of BFU-E and CFU-E using a methylcellulose culture. CCR1+ cells gave rise to BFU-E, as well as CFU-E–derived colony in the presence of Epo + SCF, whereas few CFU-E– and BFU-E–derived colonies appeared from CCR1- cells (Fig 2). The incubation with Epo + SCF, however, consistently increased to less than 20 colony-forming unit–granulocyte-macrophage (CFU-GM) colonies even at 14 days of the culture (data not shown). These results suggest that immature erythroid progenitor cells also express CCR1.

CFU-E– and BFU-E–derived colony formation by CCR1 positive or negative normal BMMNCs in the presence of Epo plus SCF. The purified CCR1 positive or negative normal BMMNCs were plated in a methylcellulose medium containing Epo and SCF. The numbers of CFU-E (open bar) and BFU-E (closed bar) were determined at day 7 or day 14 of culture, respectively. The data are representative of three independent experiments with quadruplicate determinations.

CFU-E– and BFU-E–derived colony formation by CCR1 positive or negative normal BMMNCs in the presence of Epo plus SCF. The purified CCR1 positive or negative normal BMMNCs were plated in a methylcellulose medium containing Epo and SCF. The numbers of CFU-E (open bar) and BFU-E (closed bar) were determined at day 7 or day 14 of culture, respectively. The data are representative of three independent experiments with quadruplicate determinations.

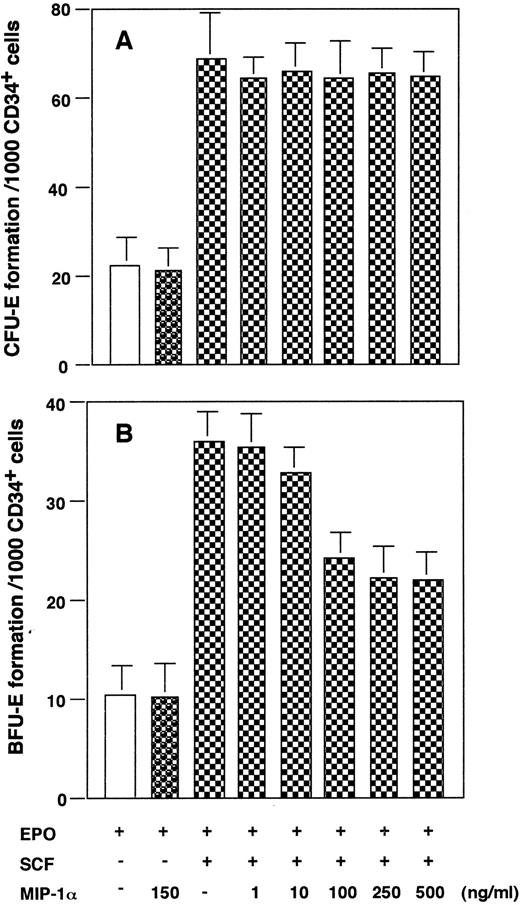

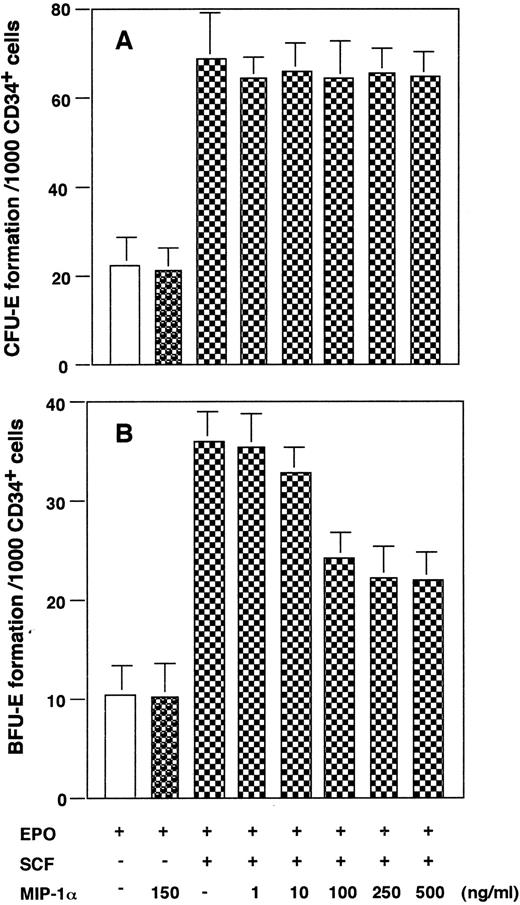

Effect of MIP-α on CFU-E– and BFU-E–derived colony formation.The presence of CCR1 on erythroid lineage cells prompted us to investigate the effects of MIP-α, a major ligand for CCR1, on in vitro erythroid colony formation by purified CD34+ cells. Epo alone induced colony formation by a small number of CFU-E, while SCF enhanced CFU-E colony formation synergistically with Epo (Fig 3A). Similar results were obtained for BFU-E–derived colony formation (Fig 3B). MIP-α inhibited BFU-E formation induced by Epo + SCF in a dose-dependent manner, exhibiting the maximal inhibition level at 100 ng/mL (Fig 3B), whereas MIP-α had negligible effects on BFU-E formation in response to Epo (Fig 3B) or CFU-E colony formation (Fig 3A). Furthermore, MIP-α decreased the frequency of BFU-E colony induced by Epo + SCF in a single cell colony assay (Table 3). These results suggest that MIP-α inhibits BFU-E–derived colony formation induced by Epo + SCF by acting directly on CD34+ erythroid progenitor cells.

Effects of MIP-α on CFU-E (A) and BFU-E (B) formation by CD34+ BMMNCs. The purified CD34+ BMMNCs were plated in a methylcellulose medium containing growth factor(s), with or without indicated concentrations of recombinant human MIP-α. The number of CFU-E and BFU-E was determined at day 7 and day 14 of culture, respectively. The data are representative of three independent experiments with quadruplicate determinations.

Effects of MIP-α on CFU-E (A) and BFU-E (B) formation by CD34+ BMMNCs. The purified CD34+ BMMNCs were plated in a methylcellulose medium containing growth factor(s), with or without indicated concentrations of recombinant human MIP-α. The number of CFU-E and BFU-E was determined at day 7 and day 14 of culture, respectively. The data are representative of three independent experiments with quadruplicate determinations.

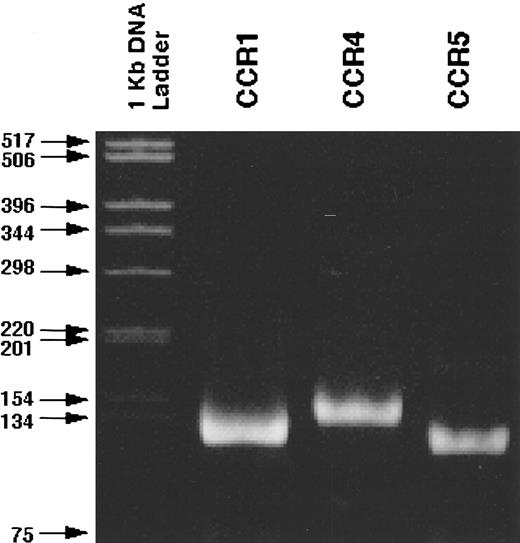

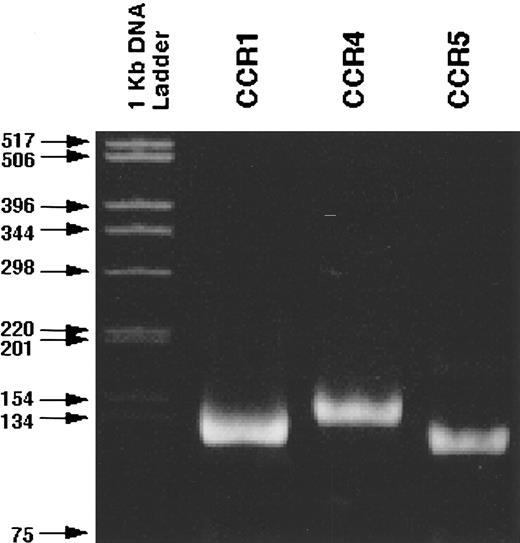

RT-PCR analysis of C-C chemokine receptor expression by CD34+ marrow cells.Because three distinct types of MIP-α receptors, CCR1, CCR4, and CCR5, have been identified, we next examined the expression of these receptor genes by RT-PCR in purified CD34+ cells using those sets of primers, which can amplify specific transcripts of each receptor gene. RT-PCR gave rise to the bands with the expected size of CCR1, CCR4, and CCR5 (Fig 4). The specificity of the amplified bands was confirmed by the determination of the nucleotide sequences of the PCR products (data not shown). Thus, CD34+ cells constitutively express all three C-C chemokine receptor genes, which can respond to MIP-α.

Detection of the transcripts of CCR1, CCR4, and CCR5 in CD34+ normal BMMNCs. RT-PCR was performed as described in Materials and Methods. The specificity of the PCR products was confirmed by the determination of their nucleotide sequence (data not shown).

Detection of the transcripts of CCR1, CCR4, and CCR5 in CD34+ normal BMMNCs. RT-PCR was performed as described in Materials and Methods. The specificity of the PCR products was confirmed by the determination of their nucleotide sequence (data not shown).

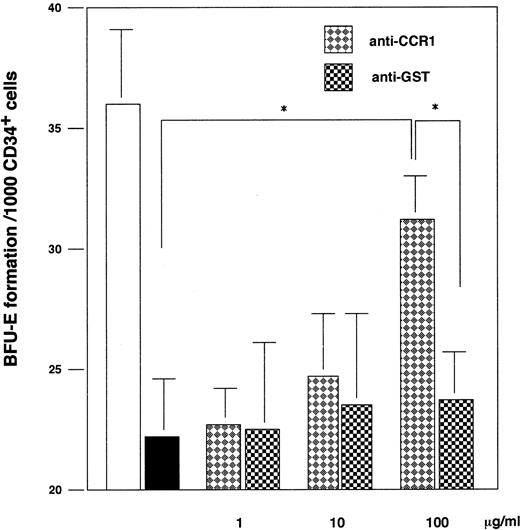

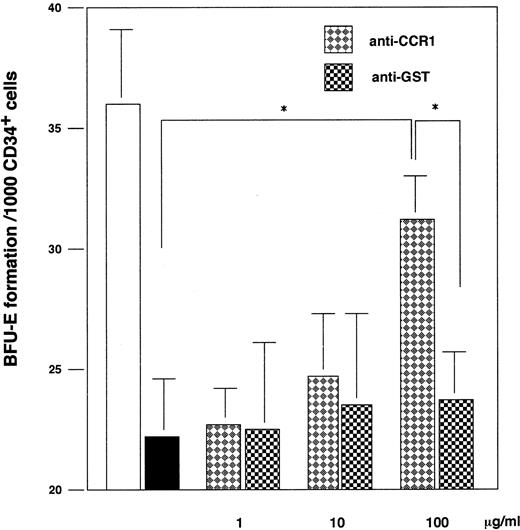

Involvement of CCR1 in MIP-α–mediated suppression of BFU-E colony formation.Finally, we explored whether CCR1 was involved in MIP-1α–mediated suppression of BFU-E–derived colony formation. In a methylcellulose culture of CD3+ cells, anti-CCR1, but not anti-GST antibodies, significantly reversed the inhibitory effects of MIP-α on BFU-E–derived colony formation in a dose-dependent manner, although the reversal was not complete (Fig 5). Similarly, anti-CCR1 antibodies significantly abrogated the inhibitory effects of MIP-α in a single cell proliferation assay (Table 3). Consequently, MIP-α suppresses BFU-E–derived colony formation by acting mainly on CCR1 on CD34+ erythroid progenitor cells, although the involvement of CCR4 and CCR5 cannot be completely excluded.

The inhibitory effects of MIP-α on BFU-E formation from CD34+ BM cells was partially abrogated by anti-CCR1 antibodies. Purified CD34+ BMMNCs were plated in a methylcellulose medium containing Epo and SCF with (solid bar) or without (open bar) recombinant human MIP-α, or a combination of the growth factors and recombinant human MIP-α with the indicated doses of anti-CCR1 antibodies (diamond bar) or control antibodies (square bar). The number of BFU-E was determined at day 14 of culture. The data are representative of three independent experiments with quadruplicate determinations. * Indicates significant difference from control culture without anti-CCR1 antibody by using one-way ANOVA analysis and multiple comparison by Fisher's method.

The inhibitory effects of MIP-α on BFU-E formation from CD34+ BM cells was partially abrogated by anti-CCR1 antibodies. Purified CD34+ BMMNCs were plated in a methylcellulose medium containing Epo and SCF with (solid bar) or without (open bar) recombinant human MIP-α, or a combination of the growth factors and recombinant human MIP-α with the indicated doses of anti-CCR1 antibodies (diamond bar) or control antibodies (square bar). The number of BFU-E was determined at day 14 of culture. The data are representative of three independent experiments with quadruplicate determinations. * Indicates significant difference from control culture without anti-CCR1 antibody by using one-way ANOVA analysis and multiple comparison by Fisher's method.

DISCUSSION

Evidence is accumulating that MIP-α has profound effects on the in vitro proliferation of hematopoietic progenitor cells, depending on their maturational stages.19-21,24 Broxmeyer et al29 observed that MIP-α suppressed BFU-E and CFU-granulocyte erythrocyte megakaryocyte macrophage (GEMM)–derived colony formation with enhancing effects on CFU-GM–derived colonies. Keller et al24 also reported that MIP-α selectively suppressed the proliferation of immature hematopoietic progenitor cells. Moreover, MIP-α is presumed to exert its myeloprotective effect through inducing immature stem cells into a quiescent state during chemotherapy.43 44 Hence, clarification of the molecular mechanism of MIP-α–mediated suppression of progenitor cell proliferation should help establish a myeloprotective regimen using MIP-α.

We previously observed that most CD34+ progenitor cells in BM and cord blood, expressed CCR1.41 Moreover, we detected CCR1 expression on glycophorin A+ erythroblasts, but not mature erythrocytes (data not shown). Because the expression of glycophorin A was restricted to basophilic normoblasts and later stages of erythrocyte differentiation, these results indicated that mature erythroblasts, but not erythrocytes, expressed CCR1. The lack of a specific MoAb to erythroid progenitor cells has prevented us from directly demonstrating CCR1 expression on immature erythroid progenitor cells by an immunofluorescence analysis. However, the CCR1- population of BM failed to give rise to BFU-E– and CFU-E–derived colonies even under the optimal condition, which was sufficient to induce BFU-E–derived colony formation in our single cell proliferation assay system. Thus, the capacity of CCR+ cells to generate erythroid colonies strongly suggests the presence of CCR1 on erythroid progenitor cells at the early committed stages. Moreover, CCR1+, but not CCR1- cells, generated a large number of CFU-GM–derived colonies when stimulated with the combination of GM-CSF, G-CSF, and IL-3, and anti-CCR1 antibodies reversed significantly MIP-α–mediated inhibition of this CFU-GM colony formation (our unpublished data). Overall, our data shows that functional CCR1 is expressed from immature erythroid progenitor cells to mature erythroblasts, in addition to immature myeloid-lineage progenitor cells.

Consistent with previous reports,20,28 the suppressive effects of MIP-α were observed for BFU-E, but not for CFU-E. Hence, BFU-E may possess a larger number of MIP-α binding sites than CFU-E, although direct demonstration was hindered by unavailability of appropriate purified cells. Alternatively, as CCR1 is a G-protein–coupled receptor, G-protein associated with CCR1 may change as progenitor cells differentiate, culminating in divergent responses to MIP-α. Moreover, because RT-PCR detected the gene expression of other MIP-α binding receptors, CCR4 and CCR5, in CD34+ cells, the relative number of each MIP-α receptor on erythroid progenitor cells may change as they differentiate, resulting in the changing sensitivity to MIP-α. This possibility is supported by the observation that the inhibitory effect of MIP-α on BFU-E formation was only partially reversed by anti-CCR1 antibodies at the dose sufficient to completely inhibit MIP-α–induced calcium mobilization in CCR1-transfectants.41 Hence, the preparation and use of specific neutralizing antibodies to CCR4 and CCR5 should facilitate a more detailed analysis of the mechanism of MIP-α–mediated suppression of erythropoiesis.

Several in vitro studies, including ours, supported the possible roles for MIP-α in hematopoiesis. However, mice deficient in MIP-α exhibited no change in peripheral blood and BM cell components,14 raising questions concerning the roles of MIP-α in normal hematopoiesis. The discrepancy may be explained by the existence of two additional MIP-α–related genes,3 which can compensate for the loss of one gene. A similar discrepancy has been observed for the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) cytokines. TNF receptor p55-deficient mice exhibited no changes in hematopoiesis despite the data showing that TNF-α modulates the in vitro proliferation of BM progenitor cells. However, our analysis showed an increase in lineage phenotype (Lin)-Sca1+c-kit+ hematopoietic stem cells in TNF receptor p55-deficient mice as compared with wild type mice, implicating TNF as a physiological negative regulator of hematopoiesis.42 Thus, a more detailed analysis of MIP-α–deficient mice might show changes in hematopoiesis, particularly concerning the differentiation pathways of erythroid cells.

Mononuclear cells from aplastic anemia patients produced a larger amount of MIP-α in response to phytohemagglutinin or lipopolysaccharide as compared with normal subjects.45,46 Moreover, an increase in MIP-α transcript expression was observed in nucleated BM cells from patients with aplastic anemia or myelodysplastic syndrome.47 These observations suggested the involvement of MIP-α overexpression in depressed erythropoiesis in these conditions. Thus, elucidation of the mechanism of MIP-α–mediated suppression of erythropoiesis, particularly with respect to the involvement of chemokine receptors, might help develop a novel type of treatment for these intractable diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Dr J.J. Oppenheim (NCI-FCRDC, Frederick, MD) for his critical review of the manuscript.

Address reprint requests to Kouji Matsushima MD, Department of Molecular Preventive Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Tokyo, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113, Japan.