Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a common cause of liver disease among polytransfused thalassemics. We treated a cohort of subjects with β-thalassemia major and chronic hepatitis C with α-interferon. The aims of the study were to assess the long-term biochemical and virologic efficacy of α-interferon and to evaluate the influence of HCV type and liver siderosis on the outcome of therapy. Seventy subjects (mean age, 14.1 years) with chronic HCV infection and abnormal aminotransferases received recombinant α-interferon for 12 months and were observed after therapy for at least 24 months. Sixty-three subjects (90%) were HCV-RNA positive at the start of therapy. HCV type 1b was found in 41 subjects (65.1%), non-1b types in 13 (20.6%), and mixed HCV types in 9 (14.3%). Liver biopsy showed cirrhosis in 11 subjects (15.7%) and siderosis grade 3-4 in 24 patients (34.2%). Three patients stopped therapy due to adverse events. Twenty-eight subjects (40%) had normal aminotransferases and had cleared HCV-RNA when last observed (mean follow-up, 36.5 months; range, 25 to 49 months). Of 41 patients who did not normalize aminotransferases, 9 had become HCV-RNA negative at the end of follow-up. The absence of cirrhosis, low liver iron content, and infection with non-1b HCV type were independently associated to complete sustained response upon multivariable analysis. In conclusion, α-interferon may induce a sustained virologic and biochemical remission of hepatitis in β-thalassemic patients with chronic HCV infection and nonadvanced liver disease.

IRON OVERLOAD and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection are the main causes of chronic liver disease in people with β-thalassemia major (βTM). HCV infection is found in more than 60% of βTM patients throughout the world.1-3

Intensive, long-lasting chelation with deferoxamine prevents or reduces iron overload and may prevent organ damage and death due to secondary siderosis.4 5

α-Interferon (IFN) is currently the first-line treatment for patients with HCV-related chronic hepatitis.6 Absence of cirrhosis and short duration of disease,7 low levels of HCV viremia,8 and infection with non-1b HCV type9 are the main clinical and virologic predictors of therapeutic efficacy. The presence of liver siderosis has recently been related to poor responsiveness to IFN in nonthalassemic subjects.10-15

Preliminary studies16-18 have shown that, in young subjects with βTM and chronic hepatitis C, IFN is well-tolerated and may normalize alanine aminotransferases (ALT) and lead to prolonged remission of liver necroinflammation at a rate comparable to that of nonthalassemic subjects with chronic hepatitis C.6

To assess the long-term biochemical and virologic efficacy of IFN, we performed a study of prolonged therapy in a large cohort of βTM subjects with chronic hepatitis C. We also evaluated, along with other clinical and laboratory features, the role of HCV type and of iron overload on the outcome of treatment.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients.All patients from six thalassemia centers were considered eligible for the study if they satisfied the following conditions: (1) diagnosis of βTM; (2) regular blood transfusions according to a standardized protocol to maintain hemoglobin level at 10 to 13 g/dL and regular therapy with deferoxamine (40 to 60 mg/kg of body weight per day administered by continuous subcutaneous overnight infusion at least 5 days per week); (3) serum ALT at least twice normal values for more than 6 months; (4) seropositivity for antibodies to HCV (anti-HCV); and (5) percutaneous liver biopsy performed within the previous 3 months showing chronic hepatitis, with or without cirrhosis.

The main exclusion criteria were HBsAg and/or HIV positivity; clinical evidence of autoimmune or metabolic liver disease; advanced or decompensated cirrhosis; diabetes; and cardiomyopathy.

The study was approved by an ethical committee. Investigative procedures were explained to each patient or to his/her parents before obtaining written informed consent for inclusion in the study.

Virologic and histologic evaluation.Anti-HCV was tested by enzyme immunoassay (EIA) and confirmed by immunoblotting (ORTHO EIA/RIBA, later EIA2/RIBA2; Ortho Diagnostics, Raritan, NJ), HBsAg, and anti-HIV 1/2 by EIA (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL). Non–organ-specific autoantibodies (nuclear, smooth muscle/actin, liver/kidney microsomes, and mitochondrial) were tested by indirect immmunofluorescence on rat organ sections. Serum ferritin, ceruloplasmin, and α1 -antitrypsin were measured by commercial assays.

Other virologic tests were performed on samples collected before, during, and after IFN treatment, which were stored unthawed at −30°C. HCV-RNA was detected in serum by nested polymerase chain reaction using a set of oligonucleotide primers synthesized from the untranslated 5′ noncoding region of the HCV genome.8 Results were expressed qualitatively. The assay detection limit was 102 to 103 genome equivalents/mL, as assessed by comparison to a EUROHEP standard.19 HCV types were identified in 63 HCV-RNA–positive subjects by reverse-hybridization line probe assay (LiPA; Innogenetics, Zwijnaarde, Belgium)20 and classified according to Simmonds et al.21

Percutaneous liver biopsies were performed with Menghini needles (Hepafix 1.6 mm; Braun Melsungen AG, Melsungen, Germany). All specimens were examined by the same pathologist and evaluated according to standardized criteria.22 Liver siderosis was graded on Perl's stained sections according to Brissot et al.23 Liver iron content (LIC) was measured in 54 subjects by atomic absorption spectrophotometry and expressed as micrograms per gram of dry tissue weight.24

Schedule of treatment and response criteria.All subjects received α2b -IFN (Intron-A; Schering-Plough, Kenilworth, NJ) at a dose of 5 MU/m2 three times weekly for 2 months, then 3 MU/msq for the following 10 months. Clinical and laboratory checks were performed monthly while on IFN and during the entire follow-up period.

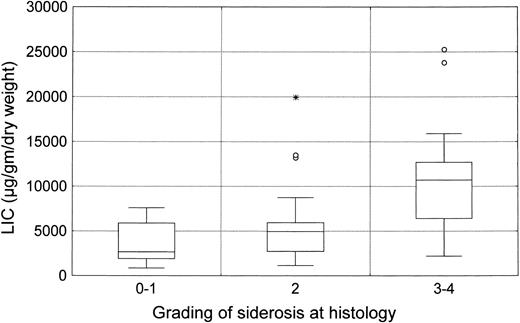

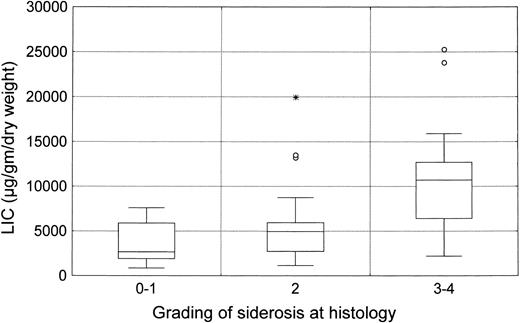

Scatter plot of the correlation between LIC and grading of liver siderosis at histology (R = .63, P < .0001).

Scatter plot of the correlation between LIC and grading of liver siderosis at histology (R = .63, P < .0001).

Evaluation of treatment efficacy was based on the effect of IFN on ALT levels and on the clearance of HCV-RNA from serum. Complete sustained response (CSR) was defined as ALT normalization persisting during the entire follow-up and negative HCV-RNA at end of follow-up. Abnormal ALT values during therapy and follow-up or any ALT relapse after stopping IFN were considered as nonresponse (NR), even if no serum HCV-RNA was detected at the end of follow-up.

Statistical analysis.Analysis of results was performed on an intention-to-treat basis. Continuous variables were expressed as the mean and standard deviation (SD). The differences between parametric data were analyzed by the Student's t-test. χ2 analysis was applied to dichotomous or categorical variables. Correlation between variables was calculated by Pearson's R for continuous and Spearman's R for categorical data. Actuarial curves were calculated according to Mantel-Haenszel's method and analyzed by the log-rank test. A multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to identify clinical features predicting CSR.

RESULTS

Features upon admission.Between January 1990 and February 1992, 70 subjects (mean age, 14.1 ± 6.5 years; range, 4 to 37 years) were enrolled by six thalassaemia centers in Western Sicily. Cirrhosis was present in 11 cases (15.7%), whereas among the subjects without cirrhosis, 16 (22.9%) had noncirrhotic fibrosis. The histologic degree of siderosis was mild in 14 (20%), moderate in 32 (45.7%), and severe in 24 (34.3%) subjects.

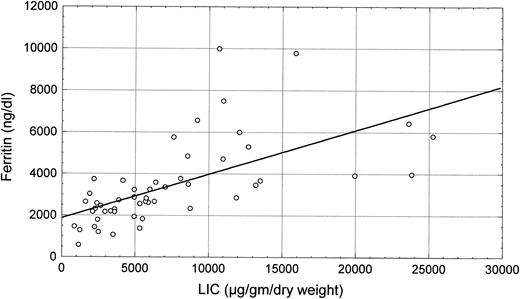

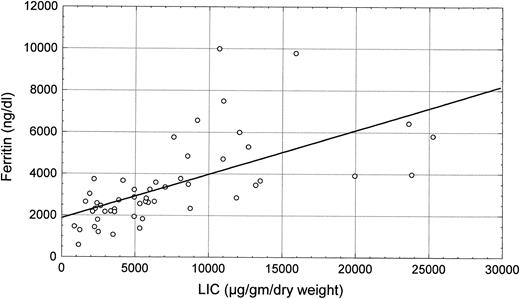

LIC (mean level, 7,255 ± 5,833 μg/g dry liver weight) was closely related to serum ferritin levels (R = .63, P < .0001; Fig 1) and to histologic siderosis (R = .56, P < .0001; Fig 2). No significant correlations were found between LIC and age (R = −.13, P = not significant [NS]) or liver structure (R = .10, P = NS).

Box plot of the relationship between LIC and serum ferritin (P < .0001 by ANOVA).

Box plot of the relationship between LIC and serum ferritin (P < .0001 by ANOVA).

Sixty-three of the 70 subjects (90%) were HCV-RNA positive when tested immediately before starting therapy. The remaining 7 who tested negative had been HCV-RNA positive both 1 to 3 months before biopsy and at biopsy itself.

Forty-one (65.1%) of the HCV-RNA–positive subjects were infected by HCV type 1b. Non-1b HCV types (type 1a, 1; type 2a/c, 7; type 3, 3; and type 4, 2) were found in 13 (20.6%) subjects. Mixed infections with different HCV types (type 1b + 2a/c, 7; type 1b + 4, 1; type 1a + 4, 1) were found in 9 (14.3%) subjects.

Pattern of response to IFN.Sixty-seven subjects completed the intended schedule of treatment. Twenty-eight (40%) subjects normalized ALT during treatment or within 3 months after stopping IFN and remained with normal ALT up to the end of the posttreatment follow-up period (mean, 36.4 months; range, 25 to 49 months). At their last follow-up visit, all 28 were HCV-RNA negative, thus fulfilling the definition of CSR.

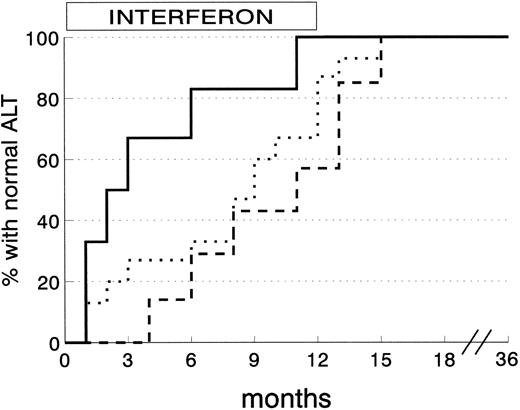

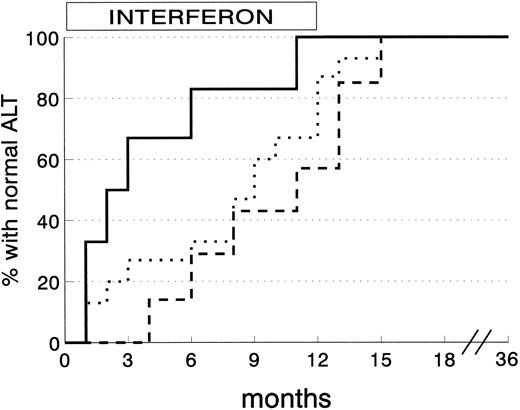

ALT normalization among 28 CSR subjects was obtained within 3 months in 8 subjects (28.6%), 6 months in 5 (17.9%), and the end of therapy in another 10 (35.6%). The remaining 5 CSR subjects (17.9%) reached normal ALT levels within 3 months of stopping IFN. The degree of liver siderosis markedly affects the kinetics of response (Fig 3). Almost all the CSR patients with mild degrees of liver iron overload responded within 4 months of therapy, whereas those with more severe siderosis were late responders.

Kinetics of ALT normalization in complete sustained response patients according to grading of liver siderosis at histology. (Solid line) siderosis grade 0-1 (6 patients); (dotted line) siderosis grade 2 (15 patients); (dashed line) siderosis grade 3/4 (7 patients) (P = .03 by log-rank test).

Kinetics of ALT normalization in complete sustained response patients according to grading of liver siderosis at histology. (Solid line) siderosis grade 0-1 (6 patients); (dotted line) siderosis grade 2 (15 patients); (dashed line) siderosis grade 3/4 (7 patients) (P = .03 by log-rank test).

Five subjects (7.2%) who normalized ALT during IFN had an ALT relapse within 6 months of stopping IFN. Abnormal ALT persisted during follow-up in these patients and all were HCV-RNA positive at their last observation.

Thirty-six subjects (51.4%) remained with abnormal ALT over the entire treatment and follow-up period. Nine of these were HCV-RNA negative at the end of follow-up.

One subject (1.4%) normalized ALT during IFN and remained with normal ALT over the entire follow-up, but was HCV-RNA positive at her last observation.

Among the 7 subjects who were HCV-RNA negative at the time of starting IFN, 5 became CSR, whereas 2 did not respond.

In 25 subjects, serial sera were available for HCV-RNA testing at 3, 6, and 12 months of therapy and at 12, 24, and 36 months of post-IFN follow-up. Twenty-three of these were HCV-RNA positive before IFN. Sixteen were CSR subjects and only 2 of these were still HCV-RNA positive at 3, 6, and 12 months of therapy. During the post-IFN follow-up, all 16 subjects were HCV-RNA negative. Nine subjects who did not normalize ALT were HCV-RNA positive before IFN. Three of these became HCV-RNA negative under therapy, but HCV-RNA reappeared in serum during the follow-up in all 3.

Predictors of CSR.To minimize potential effects of cofactors of liver damage such as siderosis, only CSR was chosen as an end-point. Clinical, laboratory, and histologic features differentiating CSR and NR subjects are shown in Table 1. Absence of cirrhosis in the pretreatment liver biopsy and infection by a non-1b HCV type were significantly more common among CSR subjects at univariate analysis. A low LIC was just short of statistical significance. Multivariate analysis confirmed absence of cirrhosis, infection by non-1b HCV type, and low LIC as variables independently associated to CSR (Table 2).

Side effects of therapy.A mild flu-like syndrome was observed in all subjects during the first 2 weeks of treatment and resolved spontaneously or after therapy with paracetamol. Two subjects discontinued IFN at 4 weeks because of persistent flu-like symptoms. One subject developed a moderate hemolytic anemia after 7 weeks of treatment, with hemoglobin levels less than 10 g/dL and positive direct and indirect Coomb's tests. Hyperhemolysis resolved after stopping IFN.

DISCUSSION

Before the introduction of compulsory testing for HCV, adolescent and adult patients with βTM received multiple blood transfusions with a high risk of HCV trasmission. Sixty percent to 80% of βTM subjects have anti-HCV–positive chronic liver disease. In 10% to 30% of these, liver biopsy shows cirrhosis.1-3 Transfusional iron overload in the liver acts as a cofactor in determining the severity of liver damage in these patients. The biochemical mechanisms involved in iron-induced hepatotoxicity and ensuing fibrosis are partially unclear. The amount of unbound transferrin iron may be directly related to the mechanism of damage.25 The increase of the pool of iron stored in the liver can alter the turnover of glutathion available to protect liver cells from lipid peroxidative processes.26 Accumulation of other trace elements or vitamin E depletion27 may be a cofactor of liver damage in iron-overloaded subjects. βTM patients with chronic hepatitis, with or without cirrhosis, may not have severe siderosis in the liver. This suggests that, particularly among the youngest βTM patients, other causes of liver damage such as hepatitis C virus may be the main offending factor, as already shown in patients with hereditary hemochromatosis.28

Because the development of cirrhosis is a multifactorial process, involving iron overload and HCV infection, both factors must be corrected to improve long-term prognosis by prevention of liver-related morbidity in older βTM subjects.29 Moreover, severe liver fibrosis limits survival after bone marrow transplantation, the only cure for βTM in young patients.30 31

Nowadays, intensive, long-lasting chelation can prevent severe hepatic iron overload and may reduce liver-related deaths due to secondary hemochromatosis.4 5

IFN is, to date, the only effective therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Meta-analysis of clinical trials6 has shown that IFN leads to sustained biochemical and virologic response in about 25% of patients. Features such as the presence of cirrhosis, long disease duration, high levels of HCV viremia, and infection by HCV type 1b7-9 are strictly related to low response to IFN. Hepatic iron overload has also been shown to correlate with a poor response to IFN in nonthalassemic patients.10-15

Our trial confirms and extends previous studies in βTM patients with chronic HCV infection16-18 that reported that a course of IFN can produce a high rate of end-of-treatment response. The sample size of our study also allows us to show good tolerability at the rather high doses used. Over a long follow-up period, we were able to show that a high CSR rate follows the end-of-treatment response. A new finding was that the rate of relapse after achieving an end-of-treatment response was definitely lower in βTM patients (18%) than that observed in nonthalassemics (50%).6

Persistent ALT normalization was usually paralleled by long-lasting HCV-RNA clearance from serum. Data obtained in the subset of patients for whom serial HCV-RNA testing was available show that, in CSR subjects, viral clearance is usually an early event, even if ALT remain abnormal for a longer period. These data also confirm that, once the virus is cleared from serum, it does not reappear while ALT remain normal.

Some patients who did not achieve a biochemical response cleared HCV-RNA after IFN therapy. The persistence of abnormal ALT in these subjects might be explained by on-going iron-induced liver damage. However, because their mean LIC was not significantly different in the pretreatment biopsy from that of CSR patients, other mechanisms of liver damage, such as HGV, might be involved.

The fact that 7 of 70 patients were HCV-RNA negative at the time of beginning IFN therapy, but had been HCV-RNA positive at the time of biopsy, might be due to fluctuations of viraemia at subliminal levels or to other interfering viral agents.

Response to IFN takes, on average, longer in βTM patients than in adult patients without hemoglobinopathies.32 If βTM subjects with CSR are analyzed according to the degree of liver iron overload, it is apparent that patients with mild siderosis tend to have an early response, similar to that of nonthalassemics. Subjects with more severe siderosis respond later, sometimes just before the end of therapy or immediately after stopping it. A practical consequence of this pattern of response is that IFN therapy for chronic hepatitis C in βTM patients should not be stopped after 3 to 4 months if ALT are still raised, as current practice dictates for nonthalassemic subjects.33 Almost 70% of CSR would probably be lost by stopping therapy after 3 months in βTM subjects with persistently abnormal ALT.

Large amounts of iron in the liver clearly reduce response to IFN, as already shown by Clemente et al.18 However, even a high LIC cannot invariably predict likelihood of nonresponse in the individual βTM patient. Hence, we believe that, when there is no evidence of severe damage in other organs, IFN therapy should not be denied even if liver iron overload is severe.

HCV is a highly heterogeneous virus21 with widely varying biologic and clinical behavior. Type 1b has been related to a more severe progression of liver disease,34 although this is not universally accepted.35 HCV 1b definitely shows less sensitivity to IFN.9 Patients with βTM included in this study had a very high rate of infection with HCV 1b, which is the most common strain in the general population in Southern Italy,36 and many of our CSR patients were also infected by this type. This is further confirmation that no single predictor of low responsiveness to IFN can be applied in clinical practice at an individual level. A point of interest is the relative paucity of mixed infections. In fact, only about 1 in 7 patients was simultaneously infected by different HCV strains. The genotyping system used in this study20 is currently acknowledged as sensitive and specific. A possible explanation might be a viral takeover phenomenon, ie, displacement of pre-existing infection by a more replication-competent HCV type. Studies are in progress on mixed infection in the liver and peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

In conclusion, our experience indicates that the cure of HCV-related liver disease in βTM patients is not an unrealistic aim and may be reached by IFN therapy in a sizable proportion of cases, especially when chronic hepatitis has not progressed to cirrhosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank David Holmes for his assistance with the preparation of this manuscript.

APPENDIX

Other clinical investigators: M. Ferraro, G. Tancredi, Centro Trasfusionale e Talassemia, Ospedale di Sciacca, Agrigento, Italy; F. Fiorenza, Centro Talassemia, Ospedale S. Elia, Caltanissetta, Italy; S. Grutta, Centro di Microcitemia, Ospedale Pediatrico G. Di Cristina, Palermo, Italy; P. Rigano, Servizio Talassemia, Ospedale V. Cervello, Palermo, Italy; L. Pitrolo, Centro di Talassemia, Ospedale Villa Sofia, Palermo, Italy; and A. Carollo, Centro di Talassemia, Ospedale S. Antonio, Trapani, Italy.

Address reprint requests to V. Di Marco, MD, Cattedra di Medicina Interna, Istituto di Clinica Medica I, Piazza delle Cliniche 2, 90127, Palermo, Italy.