Abstract

The presentation cytogenetic result was correlated with outcome for 999 patients with acute myeloblastic leukemia (AML) having bone marrow transplantation (BMT) in first complete remission (CR1). The karyotype at diagnosis was classified according to the modified Chicago classification. Allogeneic BMT (AlloBMT) was performed in 500 patients and autologous BMT (ABMT) in 499 patients. For both groups, an abnormal chromosome (abn) 5 and/or 7 or a hypodiploid karyotype had a poor outcome, whereas t(15; 17), pseudodiploidy, hyperdiploidy and diploidy were associated with a standard prognosis. Abn (16) and t(8; 21) were also of standard prognosis for ABMT, but favorable for AlloBMT. When comparing AlloBMT and ABMT in patients with favorable or standard cytogenetics, AlloBMT was of benefit for remission duration and leukemia-free survival (LFS). Patients with an unfavorable karyotype had a similar outcome, regardless of type of BMT. By multivariate analysis, cytogenetics at diagnosis had the strongest prognostic value for relapse, LFS, and survival in AlloBMT. In ABMT, cytogenetics influenced relapse and LFS. We concluded that the karyotype at diagnosis had important prognostic implication in AML grafted in CR1.

THERE IS CONTINUING debate on the optimal way of improving the outcome of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) who attain first remission (CR1). Intensification using high-dose chemotherapy (CT),1 autologous bone marrow transplantation (ABMT),2-6 or allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (AlloBMT)6-8 all have proved of value. However, these intensification therapies are associated with different antileukemic activity and toxicities. Therefore, prognostic factors would be useful to better adapt postremission therapy.

The prognostic implication of cytogenetics at diagnosis is well established for patients treated with chemotherapy.9-14 This influence of cytogenetics on outcome persists if the intention is to perform intensification therapy with BMT in CR1.15,16 Patients with monosomy or deletion of chromosome 5 and/or 7 have a recognized poor prognosis with AlloBMT.17 The effect on outcome of cytogenetics at diagnosis remains poorly documented for patients receiving ABMT. This is a report on the influence of cytogenetics on the outcome of a large number of patients with AML in CR1 intensified with either AlloBMT or ABMT. We believe the results may help in the design of a better treatment strategy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The study included 999 patients with de novo AML who had intensification with BMT in CR1 and in whom a cytogenetic report was available. These patients were transplanted between November 1980 and December 1993. For the AlloBMT group, only the patients who had a graft from an HLA-matched sibling were included. Seventy-five EBMT centers provided the data. The karyotypes were classified according to the modified Chicago classification18 on the basis of the initial cytogenetic report. The complexity classification18 has also been applied. This complexity classification includes four groups: normal, if no abnormal clone was found; simple, with a clone involving one chromosome or two chromosomes in a single translocation; complex, with clones involving two to five chromosomes; and very complex, if more than five chromosomes were involved in the abnormal clone. An abnormal clone has been defined as either (1) two or more metaphase cells with identical structural abnormalities or identical extra chromosomes, or (2) three or more metaphase cells with identical missing chromosomes. For the leukemia to be considered cytogenetically normal, at least 20 banded metaphase cells had to be analyzed and five karyotyped and found to be normal. When more than one clonal abnormality was identified, the karyotype was classified according to a single change in the hierarchical order described in the report of the sixth International Workshop on Chromosomes in Leukemia.18

Statistical methods. Data were analyzed as of September 15, 1995. Median follow-up was 4 years. Remission duration, leukemia-free survival (LFS), and survival duration from BMT were calculated by using the Kaplan and Meier product-limit method. Comparison of these data was based on results from log rank tests. The Cox regression model was applied to assess the prognostic value of patient characteristics and treatment in relation to relapse, LFS, and survival probability. Variables tested with cytogenetics at diagnosis were age, gender, white blood cell count (WBC) at diagnosis, French-American-British (FAB) classification, the time interval between diagnosis and complete remission (CR), the interval between CR and BMT, the interval between diagnosis and BMT, bone marrow purging, the conditioning for BMT, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), GVHD prophylaxis, and the year of BMT.

To detect possible influences of GVHD on outcome, patients were categorized into a group without GVHD (reference), a group with acute GVHD (aGVHD) only, a group who had acute and chronic GVHD (a/cGVHD), and a group with chronic GVHD (cGVHD) only. The endpoints were first modelled without the GVHD covariates. Subsequently, the GVHD variables were examined for additional predictive power.

RESULTS

The disease characteristics of the patients are given in Table 1. The ABMT patients were older than the AlloBMT patients, and the WBC at diagnosis was greater in the ABMT group. The time intervals from diagnosis to BMT and from CR to BMT were longer in the ABMT group. More AlloBMT patients had total body irradiation (TBI) for conditioning, whereas a busulfan-based regimen was more often used before ABMT. Cytogenetic abnormalities were detected in 496 out of 927 bone marrow samples of patients in whom an evaluable karyotype was obtained at diagnosis. In 72 patients, there were no or insufficient mitoses. The karyotypes, as classified by the modified Chicago classification, are shown in Table 2. There were no statistically significant differences in cytogenetic classes between the AlloBMT and ABMT groups. Abnormal (abn) (16) included inversion (16)(p13q22), deletion (16)(q22), and t(16; 16). Among the 72 patients with a pseudodiploid karyotype, 6 had a t(9; 22). Seven of the 24 patients in the hypodiploid group had a missing sex chromosome. Twenty-six out of the 33 patients with an abnormality in 11q had a translocation involving chromosome band 11q23. Trisomy 8 was the most frequent abnormality in the group with hyperdiploidy (41 of 96 patients).

According to the complexity classification, 326 patients had a simple karyotype abnormality, 152 patients had a complex karyotype, and in 18 patients more than five chromosomes were involved (very complex).

Cytogenetic prognostic classification. With the modified Chicago classification as a base, the patients were then further subdivided in categories for relapse, LFS, and survival probabilities (Table 3).

For AlloBMT patients, three significantly different prognostic classes could be distinguished: a good prognosis group [abn (16) and t(8; 21)], a standard prognosis group [t(15; 17), pseudodiploid, hyperdiploid, and diploid], and a poor prognosis group (abn 5 and/or 7, abn 11q, and hypodiploid). In the group that had intensification with ABMT, the most predictive classification grouped patients with abn (16), t(15; 17), t(8; 21), abn 11q, hyperdiploidy, pseudodiploidy, and a diploid karyotype. These patients could be classified in a standard prognosis group for relapse, LFS, and survival probabilities. Patients with abn 5 and/or 7 and patients with hypodiploidy were in the poor prognosis group.

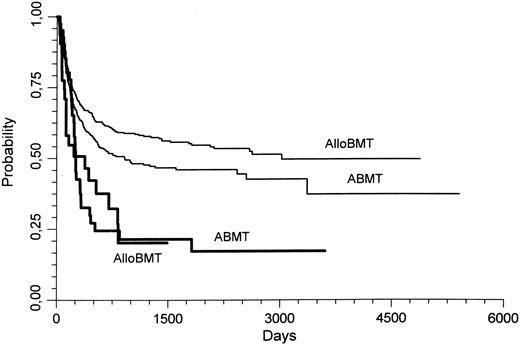

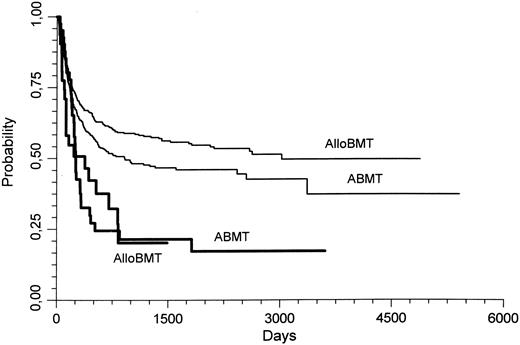

When comparing the outcome of AlloBMT and ABMT in the good and standard prognosis subgroup, the probability of relapse was significantly lower with AlloBMT (0.22 ± 0.02) than with ABMT (0.46 ± 0.02; P < .000001). This lower relapse rate persisted if only allografted patients in the standard prognosis group were considered (AlloBMT, 0.25 ± 0.02; ABMT, 0.46 ± 0.02; P = .000001). In these patients with a standard prognosis karyotype, the 3-year LFS was also better in the AlloBMT patients than in the ABMT patients (0.57 ± 0.02 v 0.48 ± 0.02, respectively, P = .04; Fig 1). However, the survival was not different.

Leukemia free survival (LFS) of patients transplanted for AML in CR1. Thin lines represent the patients who had standard prognosis cytogenetics, whereas the thick lines represent patients who had poor prognosis cytogenetics. AlloBMT, allogeneic bone marrow transplantation; ABMT, autologous bone marrow transplantation. In patients with a standard prognosis karyotype, the 3 year LFS was better with AlloBMT than with ABMT (P = .04).

Leukemia free survival (LFS) of patients transplanted for AML in CR1. Thin lines represent the patients who had standard prognosis cytogenetics, whereas the thick lines represent patients who had poor prognosis cytogenetics. AlloBMT, allogeneic bone marrow transplantation; ABMT, autologous bone marrow transplantation. In patients with a standard prognosis karyotype, the 3 year LFS was better with AlloBMT than with ABMT (P = .04).

In the patients with a poor prognosis karyotype, there were no significant differences between AlloBMT and ABMT for relapse, LFS, or survival probabilities.

When examining the outcome after AlloBMT and ABMT according to the cytogenetic abnormality, the differences were as follows: Among the patients with abn (16), AlloBMT patients had a better outcome than ABMT patients for relapse and LFS probability. AlloBMT patients with t(8; 21) and with hyperdiploidy had a lower relapse probability than the patients who had ABMT, but their LFS and survival probability were not significantly different. With a diploid karyotype, AlloBMT had a better outcome than ABMT for relapse, LFS, and survival probabilities. ABMT gave a better survival probability than AlloBMT in the patients with a t(15; 17) (Table 4).

The patients in whom no or insufficient mitoses were found had a relapse, LFS, and survival probability of 0.42 ± 0.02, 0.44 ± 0.06, and 0.44 ± 0.06, respectively.

With the complexity classification, only the 18 patients with a very complex karyotype had a worse outcome for remission duration, LFS, and survival, regardless of the type of BMT.

Cytogenetics did not influence the treatment-related mortality.

Associations with cytogenetics. Associations with cytogenetics and other disease characteristics were FAB classification M3 with t(15; 17)(P < .0000001) and t(8; 21) with M2 (P = .002). There was also an association between abn (16) and M4 (P < .0000001) and a relationship between abn 11q and M4/M5 (P = .0002). No other significant associations were found.

Prognostic factors other than cytogenetics: Univariate analysis. In the AlloBMT patients, cytogenetics, cGVHD, and FAB classification had prognostic value for relapse, LFS, and survival. Age had influence on LFS and survival. A longer interval between diagnosis and the attainment of CR adversely affected LFS and survival. A lower relapse rate was observed with a longer time interval between CR1 and BMT. Patients who had an allograft later than January 1, 1989 had a better survival probability (Table 5).

In the ABMT patients, cytogenetics, FAB M3, and the time interval between CR1 and ABMT influenced relapse, LFS, and survival (Table 6).

Conditioning, bone marrow purging, or the type of GVHD prophylaxis did not influence outcome.

Prognostic factors: Multivariate analysis. For AlloBMT, cytogenetics, the occurrence of a/cGVHD and cGVHD not preceded by a GVHD had independent value for relapse, LFS, and survival. Age remained a significant prognostic factor for survival, and a long time interval between CR and AlloBMT was of favorable prognosis for remission duration (Table 7).

In the ABMT patients, cytogenetics retained prognostic importance for relapse and LFS, but not for survival. FAB M3 was of favorable prognosis for survival, LFS, and relapse. A long delay between CR and ABMT was associated with longer survival (Table 8).

DISCUSSION

An important question in the field of stem cell transplantation is whether prognostic factors previously recognized to predict for response to CT might also predict for response to transplantation. Particularly, it would be important to define the patients who would not need a transplant, and conversely select patients who, despite poor results with CT, would be advantaged by intensive therapy followed by stem cell transplantation.

In AML, the prognostic value of cytogenetics has been established in patients treated with chemotherapy.9-14 The relevance of cytogenetics for stem cell transplantation has been reported recently by the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry (IBMTR)17: abn 5 and/or 7, known to be associated with secondary leukemias and with a poor prognosis in patients treated with CT, also predict for poor outcome with AlloBMT. However, this study did not consider ABMT and therefore, could not compare the potential prognostic value of cytogenetics in relation to the type of transplant performed.

We reviewed the registered data from 999 patients reported to the EBMT, in whom results of cytogenetics were available. We first classified the karyotypes according to the modified Chicago classification18; we then subdivided the patients into groups discriminating best for outcome post-AlloBMT and post-ABMT; finally, we tested in a Cox regression model all factors possibly influencing the outcome, including cytogenetics.

Three cytogenetic categories were defined for AlloBMT (good, standard, and poor) and only two categories for ABMT (standard and poor). Abn (16) and t(8; 21), defining the good risk category for AlloBMT, were standard risk for ABMT. Abn 5 and/or 7, already recognized as poor risk factors for AlloBMT as well as hypodiploidy, so far not classified in this respect, were also poor risk factors for both AlloBMT and ABMT. With the exceptions noted above, the standard risk group was similar for both transplant modalities, including t(15; 17), pseudodiploidy, hyperdiploidy, and diploidy.

These categories were highly predictive for relapse with, for AlloBMT, increasing relapse rates from 9% in the good risk group to 25% in the standard risk group and to 61% in the poor risk group. After ABMT, the relapse incidences were higher, ie, 46% in the standard group and 77% in the poor risk group. The higher frequencies of relapse in the standard risk categories resulted in a reduced LFS after ABMT compared with AlloBMT. However, poor risk patients showed similar unfavorable LFS and survival after AlloBMT and ABMT.

By multivariate analysis, poor cytogenetics was the strongest unfavorable prognostic factor for relapse in the AlloBMT group with a relative risk of 2.66. The other independent poor risk factors were the absence of aGVHD and/or cGVHD and a short interval from CR to BMT. Besides cytogenetics, the only other independent poor risk factor for relapse after ABMT was a FAB type other than M3. The favorable impact of M3 in ABMT has already been noted.19

Patients with poor cytogenetics had a similar bad outcome with either AlloBMT or ABMT. In contrast, the vast majority of patients that constitute the standard group had a better LFS after AlloBMT than after ABMT. Furthermore, the relapse rate was very low after AlloBMT for abn (16) or t(8; 21).

The study from the IBMTR suggested that the prognostic factors for AlloBMT, including cytogenetics, were not different from those recorded with chemotherapy.17 Indeed, patients with abn 5 and/or 7 did poorly in this study both with AlloBMT and ABMT. Comparison of published data on the outcomes after chemotherapy and the present BMT data shows that the prognostic implication of abn (16) was similar with both intensification modalities.9,10,14-16 However, the present study shows that BMT patients with a hypodiploid karyotype did also have a poor prognosis. For the majority of patients, ie, those with a diploid karyotype, the outcome appears better with BMT than with CT.9,12,14 In addition, patients with a hyperdiploid and a pseudodiploid karyotype also had a better outcome with BMT than that expected with CT.9-12 Nevertheless, it is clear that an advantage of BMT in CR1 over CT in these patients with either a pseudodiploid, a hyperdiploid, or a diploid karyotype can only be proven by a prospective randomized trial.

It is tempting to speculate that the 23% survival probability equivalent for AlloBMT and ABMT in the poor risk group may still offer some advantage over CT. The similarly poor prognosis in AlloBMT and ABMT patients would not justify a search for an unrelated donor in absence of a family donor. Considering the good prognosis of patients with abn (16) or t(8; 21) with CT, it is reasonable to spare them the toxicity of BMT, and especially the toxicity of AlloBMT in CR1. In view of the promising results of all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA)-based regimens in patients with t(15; 17),20 the indications for BMT in CR1 may disappear in these patients, except perhaps in those presenting with a high WBC, with blasts expressing CD13 or with bcr3-type rearrangement.21 The low toxicity of ABMT in patients with M3 is noteworthy.

Both cytogenetics and GVHD had prognostic value in AlloBMT patients. There was however no association between karyotype and GVHD, and therefore, the favorable effect of a standard or good prognosis karyotype on relapse, in comparison with ABMT, is largely because of GVHD and/or graft-versus-leukemia (GVL).22-24 Why patients with a standard or good prognosis karyotype were more prone to these favorable effects than patients with a poor prognosis karyotype remains a matter of speculation.

The cytogenetic classification on which this study was based was the modified Chicago classification. This classification individualizes the most frequent cytogenetic abnormalities in AML, and offers more detailed information than the NN, AN, AA classification (only normal cells, admixture of normal and abnormal cells, only abnormal cells); the complexity classification; or other classifications. However, it will be improved with further knowledge of the cytogenetics of AML.25-30 In this respect, it is probable that t(9; 22) and t(6; 9) will have to be withdrawn from the heterogeneous pseudodiploidy group. Lumping together patients with different rare cytogenetic abnormalities into broad prognostic categories is a further simplification. These prognostic categories might have their inclusion criteria modified and their significance better precised when more patients with these infrequent cytogenetic abnormalities will have been studied.

As with all studies from registries, the present one has limitations: Cytogenetic studies were performed at many laboratories and selection of patients was likely. Nonetheless, the high level of significance observed makes cytogenetics the most important prognostic factor to consider with regard to transplant. Randomized prospective studies addressing the comparative value of intensification with CT, AlloBMT, and ABMT, with stratification of the patients by cytogenetics, are now needed to better define the optimal indication for each treatment modality.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr Lucienne Michaux for her advice in the classification of the karyotypes.

APPENDIX

The following EBMT centers contributed to this study by reporting patients with cytogenetic reports: Cliniques Universitaires St Luc, Bruxelles, Belgium: 75; Ospedale San Martino, Genova, Italy: 53; Hôpital Saint-Antoine, Paris, France: 52; Royal Free Hospital, London, UK: 48; Hôpital Jean Minjoz, Besançon, France: 46; Institut Paoli-Calmettes, Marseille, France: 42; Hôpital du Haut-Levêque, Pessac, France: 41; Ospedale St Orsola, Bologna, Italy: 35; Hospital Universitari La Fe, Valencia, Spain: 34; University Hospital, Leuven, Belgium: 32; Dr Daniel den Hoed Kliniek, Rotterdam, The Netherlands: 32; University Hospital St Radboud, Nijmegen, The Netherlands: 28; Centre Hospitalier Universitaire, Nancy, France: 25; University College Hospital, London, UK: 24; University Hospital, Utrecht, The Netherlands: 24; Hôpital St Jacques, Nantes, France: 24; Hôpital Edouard Herriot, Lyon, France: 22; Hôpital de Purpan, Toulouse, France: 20; Hôpital de Hautepierre, Strasbourg, France: 20; Huddinge Hospital, Huddinge, Sweden: 18; Rikshospitalet, Oslo, Norway: 17; Kantonsspital, Basel, Switzerland: 14; Hôpital Claude Hurriez, Lille, France: 13; Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander, Spain: 12; Hôpital Nord, St Etienne, France: 12; Medizinische Hochschule, Hannover, Germany: 12; Universitätsspital, Innsbruck, Austria: 11; Ospedale San Camillo, Roma, Italy: 11; Clinical Hospital Center-Rebro, Zagreb, Yugoslavia: 11; Centre Hospitalier, Angers, France: 10; Hôpital Saint-Louis, Paris, France: 9; Hôpital Henri Mondor, Créteil, France: 9; Royal Infirmary, Edinburgh, UK: 8; Università de Milano, Milano, Italy: 8; University Hospital, Uppsala, Sweden: 8; University Hospital, Leiden, The Netherlands: 8; Università Cattolica S. Cuore, Roma, Italy: 7; Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa: 7; Hôpital de Cimiez, Nice, France: 7; Centre Georges François Leclerc, Dijon, France: 7; Università degli Study, Parma, Italy: 6; Hospital Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona, Spain: 6; Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle, UK: 6; University Hospital, Lund, Sweden: 6; Klinikum Grosshadern, München, Germany: 6; The Queen Elisabeth Hospital, Woodville, Australia: 6; Glasgow Royal Infirmary, Glasgow, UK: 5; Hôpital Bretonneau, Tours, France: 5; Instituto Portugues de Oncoligia, Lisbon, Portugal: 5; Hospital Clinic, Barcelona, Spain: 4; St James's Hospital, Dublin, Ireland: 4; East Birmingham Hospital, Birmingham, UK: 4; Silesian Medical Academy, Katowice, Poland: 4; Pitié-Salpétrière, Paris, France: 3; The George Papanicolaou Hospital, Thessaloniki, Greece: 3; Academic Hospital, Maastricht, The Netherlands: 3; Hôpital Paul Brousse, Villejuif, France: 3; University Central Hospital, Turku, Finland: 2; Centre Jean Perrin, Clermont-Ferrand, France: 2; Ospedale di Niguarda, Milano, Italy: 2; Charing Cross-Westminster, London, UK: 2; Hospital Nostra Senora del Pino, Las Palmas, Spain: 2; Hôpital Augustin Morvan, Brest, France: 2; Medizinisches Universitäts-Klinik, Ulm, Germany: 1; Università di Torino, Torino, Itlay: 1; Hôpital Cantonnal Universitaire, Genève, Switzerland: 1; Centro Leucemie Infantili, Padova, Italy: 1; Ospedale San Maurizio, Bolzano, Italy: 1; National Institute of Hematology, Budapest, Hungary: 1; Hospital M. Infantil Vall d'Hebron, Barcelona, Spain: 1; Royal South Hants Hospital, Southampton, UK: 1; Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge, UK: 1; Klinikum Nürnberg, Nürnberg, Germany: 1; Institut Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France: 1; Centre Hospitalier Universitaire, Reims, France: 1.

Supported by Grants No. 7.4555.95, FNRS Télévie, No. 6113 ARC, Villejuif, and EBMT funds.

Address reprint requests to A. Ferrant, MD, Department of Hematology, Cliniques Universitaires St Luc, 10 avenue Hippocrate, 1200 Brussels, Belgium.