Abstract

Recent studies have documented an increased risk of therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myelogenous leukemia (t-MDS/AML) after autologous bone marrow transplant (ABMT) for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL). To develop methods to identify patients at risk for this complication, we have investigated the predictive value of clonal bone marrow (BM) hematopoiesis for the development of t-MDS/AML, as defined by an X-inactivation based clonality assay at the human androgen receptor locus (HUMARA), in a group of patients undergoing ABMT for NHL from a single institution (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA). One hundred four female patients were analyzed. At the time of ABMT, the prevalence of polyclonal hematopoiesis was 77% (80/104), of skewed X-inactivation pattern (XIP) was 20% (21/104), and of clonal hematopoiesis was 3% (3/104). To determine the predictive value of clonality for the development of t-MDS/AML, a subgroup of 78 patients with at least 18 months follow-up was analyzed. As defined by the HUMARA assay, 53 of 78 patients had persistent polyclonal hematopoiesis, 15 of 78 had skewed XIP, and 10 of 78 (13.5%) either had clonal hematopoiesis at the time of ABMT or developed clonal hematopoiesis after ABMT. t-MDS/AML developed in 2 of 53 patients with polyclonal hematopoiesis and in 4 of 10 with clonal hematopoiesis. We conclude that a significant proportion of patients have clonal hematopoiesis at the time of ABMT and that clonal hematopoiesis, as detected by the HUMARA assay, is predictive of the development of t-MDS/AML (P = .004).

THE USE OF AUTOLOGOUS bone marrow transplant (ABMT) is increasing in the treatment of lymphoma and in solid tumors. ABMT is an accepted therapy for aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) and refractory Hodgkin's disease, with cures rates approaching 40% to 50% in patient subgroups in which the expected survival was lower than 20%.1-3 Based on this success and on the low treatment associated mortality, the role of ABMT is currently being investigated for low- and intermediate-grade NHL in relapse4 and in first remission.5 Furthermore, the use of ABMT is increasing in breast cancer patients with metastatic disease as well as in high-risk patients with early stage disease.6

A counterpoint to the success of intensive therapy has been the emergence of long-term complications in a significant number of cured patients, the most serious of which is an increased risk to develop a secondary neoplasm.7,8 Therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia (t-MDS/AML) account for a significant proportion of therapy-induced cancers in this population.9-11 The exact incidence of t-MDS/AML after ABMT for NHL is unknown, because ABMT is a relatively new procedure and follow-up is not sufficiently long. Nevertheless, this life-threatening complication has been reported with increasing frequency,12-14 with two groups reporting actuarial incidences as high as 15% to 18% at 5 and 6 years.12,13Of equal concern are the recent reports of t-MDS/AML after high-dose chemotherapy and ABMT in breast cancer patients.15 These reports are of particular concern in patients with metastatic breast cancer and high-risk patients with early stage disease, in which the benefit of ABMT is not yet clearly established.

The etiology of t-MDS/AML in this patient population is unresolved. Although t-MDS/AML in NHL patients has occurred as soon as several months after transplant, the interval from initial therapy to the development of t-MDS/AML ranges from approximately 4 to 7 years. This interval corresponds to the typical alkylating agent-related MDS incubation period in the nontransplant setting.16 Stone et al12 have suggested that bone marrow (BM) stem cell damage sustained before the transplant may be an important risk factor and that the increased risk of t-MDS/AML is primarily the result of the reinfusion of damaged stem cells. Other investigators believe that t-MDS/AML is primarily a consequence of cell damage caused by total body irradiation14 17 or the ABMT conditioning regimen. Further studies are needed to distinguish the role of prior therapy from the role of ABMT in the pathogenesis of t-MDS/AML.

MDS and AML are clonal disorders affecting an early hematopoietic progenitor cell. Preliminary data suggest that clonal derivation of hematopoietic cells is an early event in the development of t-MDS/AML and may be predictive of outcome.18-21 To address this question, we have performed clonality analysis in the BM of female patients with NHL undergoing ABMT at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI). X-chromosome inactivation–based clonality assays are ideally suited for this analysis, because they do not rely on any specific tumor marker. This study used the X-inactivation–based human androgen receptor clonality assay (HUMARA), which offers several advantages over other X-inactivation–based assays because it is polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based and has a high rate of heterozygosity (>90%) as a consequence of more than 20 alleles generated by the different number of trinucleotide repeats at this locus in the general population.22 Furthermore, this assay has been validated in the analysis of hematopoiesis and in various hematologic disorders.23-28 One potential limitation of X-inactivation assays is excessive Lyonization. Lyonization is the random inactivation of the X-chromosome in females that occurs early in embryogenic development. Excessive Lyonization refers to females who have randomly inactivated a preponderance of one X-chromosome (either the paternal X or the maternal X) relative to the other, leading to a skewed X-inactivation pattern (XIP). A pattern of skewed X-inactivation can mimic clonal derivation of cells. Recent studies have shown that skewed XIP occurs at a higher frequency than previously thought. Gale et al29 found significant skewed XIP in 23% of normal females using PGK and HPRT probes. In addition, skewed XIP has recently been shown to increase with age, with greater than 30% of the normal population having skewed XIP at 60 years.30 The significance of acquired skewed XIP remains to be determined, but this finding has important implications for X-inactivation clonality assays: constitutional excessive Lyonization as well as acquired skewed XIP of polyclonal cells can only be distinguished from clonal cells using appropriate tissue controls. Because X-inactivation patterns may vary from tissue to tissue,31 somatic control from embryologically related tissue (such as T lymphocytes or buccal mucosa cells) is needed to interpret skewed patterns of X-inactivation in BM cells. The goal of this study was to determine the incidence of clonal hematopoiesis in this patient population and whether clonal hematopoiesis, detected by X-inactivation clonality assays, was predictive of t-MDS/AML.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Selection and Study Design

BM and peripheral blood was collected from every female patient with NHL undergoing ABMT at the DFCI between 1987 and 1996 who had a BM sample before ABMT available. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. Patients were considered evaluable if they had a pre-ABMT BM sample available for analysis and mononuclear blood cells (MNBCs) in cases of skewed pattern of X-inactivation. MNBCs were analyzed in every patient with a preABMT BM ratio greater than 3. All patients with a polyclonal ratio or with skewed XIP pre-ABMT were assessed for clonal evolution using the most recent BM specimen available.

Therapies before ABMT were heterogeneous, as patients were treated according to several institutionally approved protocols before ABMT. The ABMT conditioning regimen in all patients consisted of cyclophosphamide at 60 mg/kg/d for 2 days and total body irradiation administered in fractionated doses (total of 1,200 cGy for patients transplanted before 1995 and of 1,400 cGy after 1995). This was followed by reinfusion of the previously harvested autologous BM that had been purged with anti–B-cell monoclonal antibodies. Follow-up, including clinical status, complete blood count, BM report, and cytogenetics when available, was obtained from chart review. MDS was diagnosed using the standard French-American-British (FAB) criteria.

Sample Processing and DNA Isolation

DNA from BM and MNBCs was obtained as previously described.32 Cells were isolated by density gradient centrifugation on a Ficoll/Hypaque gradient (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). Granulocyte contamination of the MNBCs was less than 1% in greater than 90% of samples (range, 0% to 4%). Cells were centrifuged, the cell pellet was lysed, and DNA was extracted with phenol/chloroform, precipitated with 2 vol of absolute ethanol, 1/10 vol of 3 mol/L sodium acetate, and glycogen. DNA was then washed with ethanol 70% and resuspended in H2O.

HUMARA Clonality Assay

Clonality assay of the HUMARA gene. (A) HUMARA locus on X chromosome. The first exon of the human androgen receptor gene contains a highly polymorphic CAG repeat with more than 20 different alleles and a heterozygosity frequency of 90%. One hundred base pairs 5′ to the (CAG)n lies a site of differential methylation between Xa (X active) and Xi (X inactive). The HUMARA assay has reliable methylation patterns that have been documented using an androgen receptor expression assay at the same locus. Within the differential methylation site are 2 restriction sites for the methylation sensitive restriction endonuclease Hpa II. Hpa II will cleave unmethylated, active X alleles, precluding amplification of these alleles by PCR primers 1 and 2. (B) The HUMARA clonality assay. DNA is digested with Hpa II and amplified by PCR using 32P end-labeled primers. In a polyclonal population of cells (b), both the maternal (M) and paternal (P) X alleles (X inactive) will be amplified and discriminated as two bands of different molecular weight on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel by the variable CAG repeat. In contrast, for a clonal population of cells (a and c), in which all cells are derived from a single common progenitor, only the maternal or paternal allele (X inactive) will be amplified, giving a single band. In accordance with published literature, patients are considered to have clonal hematopoiesis if the corrected allelic ratio (Cr) is greater than 3:1. Ratios between 1:1 and 3:1 (ie, between 1 and 3) are considered to represent polyclonal hematopoiesis ([▪] paternal allele; [□] maternal allele; large open box denotes longer CAG expansion associated with paternal allele; small hatched box denotes shorter CAG expansion associated with maternal allele; slash mark indicates active unmethylated allele cleaved by Hpa II).

Clonality assay of the HUMARA gene. (A) HUMARA locus on X chromosome. The first exon of the human androgen receptor gene contains a highly polymorphic CAG repeat with more than 20 different alleles and a heterozygosity frequency of 90%. One hundred base pairs 5′ to the (CAG)n lies a site of differential methylation between Xa (X active) and Xi (X inactive). The HUMARA assay has reliable methylation patterns that have been documented using an androgen receptor expression assay at the same locus. Within the differential methylation site are 2 restriction sites for the methylation sensitive restriction endonuclease Hpa II. Hpa II will cleave unmethylated, active X alleles, precluding amplification of these alleles by PCR primers 1 and 2. (B) The HUMARA clonality assay. DNA is digested with Hpa II and amplified by PCR using 32P end-labeled primers. In a polyclonal population of cells (b), both the maternal (M) and paternal (P) X alleles (X inactive) will be amplified and discriminated as two bands of different molecular weight on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel by the variable CAG repeat. In contrast, for a clonal population of cells (a and c), in which all cells are derived from a single common progenitor, only the maternal or paternal allele (X inactive) will be amplified, giving a single band. In accordance with published literature, patients are considered to have clonal hematopoiesis if the corrected allelic ratio (Cr) is greater than 3:1. Ratios between 1:1 and 3:1 (ie, between 1 and 3) are considered to represent polyclonal hematopoiesis ([▪] paternal allele; [□] maternal allele; large open box denotes longer CAG expansion associated with paternal allele; small hatched box denotes shorter CAG expansion associated with maternal allele; slash mark indicates active unmethylated allele cleaved by Hpa II).

Kinasing primer protocol.

Two microliters (5 pmol/μL) of primer HUMARA I was added to 10× kinase buffer (1 μL; Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN), γ-32P dATP (6 μL, 3,000 μCi/ mmol), polynucleotide kinase (0.6 μL; Boehringer Mannheim), and H2O (0.8 μL), followed by incubation at 37°C for 30 minutes.

Precutting of genomic DNA.

Genomic DNA was precut by mixing sample DNA (100 ng to 1 μg in 2 μL) with Hpa II (1 μL, high concentration, 40 U/μL),Rsa I (0.5 μL, high concentration, 40 U/μL), L buffer (2 μL; Boehringer Mannheim), and H2O (14.5 μL). An auto-control was precut in the same way, except that Hpa II was omitted from the mix. Samples were incubated at 37°C overnight.

PCR amplification of the HUMARA locus.

Two microliters of digested DNA was added to 23 μL of a PCR mix containing buffer (10×: 500 mmol/L NaCl, 100 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.2, 15 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.1% gelatin); dNTPs (200 μmol/L each); primer HUMARA I (5′-GCTGTGAAGGTTGCTGTTCCTCAT-3′) and primer HUMARA II (5′-TCCAGAATCTGTTCCAGAGCGTGC-3′) (12.5 pmol each); dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; 0.75 μL; Sigma, St Louis, MO); γ-32P end-labeled HUMARA I primer (1.25 pmol); AmpliTaq polymerase (0.5 U; Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, CT); and H2O to final volume of 23 μL. Samples were amplified on a programmable thermal cycler (MJ Research, Inc, Watertown, MA) with initial DNA denaturation at 94°C for 3 minutes and then for 39 cycles starting with 94°C for 45 seconds, 60°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds. At the end of amplification, 12.5 μL of formamide loading buffer (95% formamide, 20 mmol/L EDTA, 0.05% bromophenol blue, 0.05% xylene cyanol) was added to each sample, and samples were denatured at 95°C for 3 minutes and chilled rapidly. Amplified PCR products (10 μL) were electrophoresed on a 4% acrylamide-urea-formamide denaturing gel at 70 W for 3 hours.

Samples in which no satisfactory PCR product was obtained were amplified using a nested PCR amplification. Reaction mixtures were essentially identical to the ones used for regular PCR, except that only 1 μL of digested DNA was added to the cold mix and only 29 cycles were performed. The primers used were primer HUMARA III (5′-GTTAGGGCTGGGAAGGGTCT-3′) and primer HUMARA IV (5′-TCTGGGACGCAACCTCTCTC-3′). Cold PCR was followed by a regular PCR using diluted (1/25) amplified products and, again, only 29 cycles were performed. Samples were then processed as described above.

Quantitation of Alleles

Dried gels were exposed to a phosphor screen for 24 hours and scanned on a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). Ratios between the two X-linked alleles were measured using ImageQuant software. The allele ratio was defined as the ratio between the two X-linked alleles in a given sample. The corrected ratio (Cr) was defined as the allele ratio of the precut sample divided by the allele ratio of the non-precut sample of the same specimen. This ratio compensates for potential preferential amplification of one of the two alleles. Samples were analyzed in duplicate with less than 5% variance in allelic ratios in replicate samples.

Clonality Ratios

The distinction between polyclonal and clonal hematopoiesis using the HUMARA assay was defined using the following criteria. A test result of polyclonal hematopoiesis was defined as BM ratios ≤3:1. BM ratios greater than 3:1 were considered to be consistent with either skewed XIP or clonal hematopoiesis. A test result of clonal hematopoiesis was defined as BM ratios greater than 3:1 with MNBC ratios ≤3:1, whereas a test result of skewed XIP was defined as BM ratios greater than 3:1 with MNBC ratios greater than 3:1. A BM ratio increasing threefold or greater in three serial measurements over time in a patient with skewed XIP was considered to represent clonal evolution. Polyclonal hematopoiesis or clonal hematopoiesis in the text refers to polyclonal hematopoiesis or clonal hematopoiesis as defined by the HUMARA assay. Skewed XIP in this context can be the consequence of either constitutional excessive Lyonization or acquired skewed XIP.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed to compare the MDS patients with HUMARA allelic BM ratios ≤ 3:1 (polyclonal group) to MDS patients with allelic BM ratios greater than 3:1 with MNBC ratio ≤ 3:1 (clonal group). The incidence of t-MDS/AML between the clonal population and the polyclonal population was compared using the two-tailed Fisher's exact test.

RESULTS

X-Inactivation Clonality Ratios

The incidence of clonality at the time of ABMT.

One hundred eleven patients had a BM sample available before ABMT. The median age of the patients was 48 years (range, 26 to 68 years). Of these 111 patients, 110 were evaluable based on availability of MNBC control and, of these 110 patients, 104 (94.5%) were informative for the HUMARA locus (heterozygous). MNBCs were analyzed in 36 of 104 cases, including all of the nonpolyclonal cases. Polyclonal hematopoiesis was present in 77% (80/104), skewed XIP in 20% (21/104), and clonal hematopoiesis, as defined by the HUMARA assay, in 3% (3/104). The cytogenetic analysis of these three clonal patients was as follows: 1 patient had no cytogenetics performed before ABMT, 1 patient had normal cytogenetics 1 month before ABMT, and the third patient (patient no. 34) had normal cytogenetics before ABMT but developed an abnormal clone with del(13) 7 months afterwards. Because patient no. 34 was transplanted before 1995, she was part of the cohort of patients analyzed for the predictive value of the HUMARA assay.

Clonal evolution in patients.

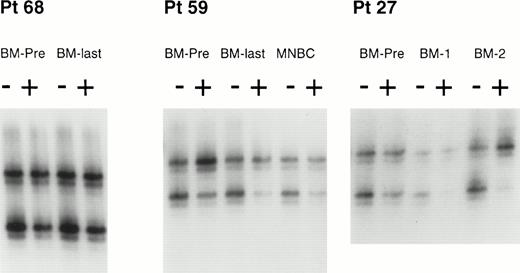

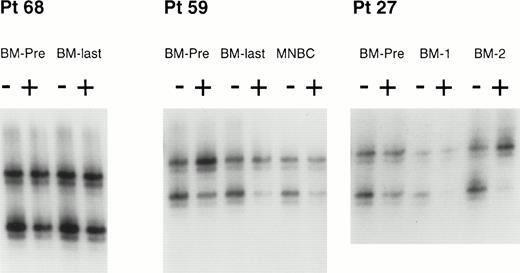

To determine the predictive value of the clonality assay, we analyzed a subgroup of 84 patients with a BM sample available before ABMT and at least 18 months of follow-up for the development of t-MDS/AML (ABMT before 1995). Of 83 evaluable patients, 78 (94%) were informative at the HUMARA locus. Polyclonal hematopoiesis was found in 59 patients and skewed XIP was found in 18; 1 patient had clonal hematopoiesis, by test criteria, before ABMT. However, during the posttransplant course, 6 patients with prior polyclonal hematopoiesis and 3 patients with skewed XIP developed clonal derivation of cells (Table 1). Thus, altogether, 10 of 78 (13.5%) patients developed clonal hematopoiesis at some point in their clinical course. An example of clonality analysis by the HUMARA assay in 3 selected patients is shown in Fig 2.

Clonal analysis by the HUMARA assay of BM and MNBCs from 3 patients. HUMARA alleles were amplified by PCR in the absence (−) or in the presence (+) of Hpa II. The ratio of digested DNA/undigested DNA allows to correct for the potential preferential amplification of one allele over the other that occurs frequently. Shadow bands result from slippage of DNA polymerase during PCR amplification. In patient no. 68, both the pre-ABMT BM sample (BM-PRE) and the last available BM (BM-LAST) showed balanced methylation patterns, consistent with polyclonal hematopoiesis before and after ABMT. In patient no. 59, the pre-ABMT BM sample, the last available BM sample, and the MNBC control sample showed an inbalanced methylation pattern, with the predominance of the upper allele, consistent with a skewed XIP. In patient no. 27, the pre-ABMT BM sample showed a balanced methylation pattern (polyclonal hematopoiesis), but subsequent BM samples obtained after ABMT (BM-1 and BM-2) showed a progressive predominance of the upper allele. Thess results are consistent with the development of clonal hematopoiesis after ABMT. See text for definitions of skewed XIP, polyclonal hematopoeisis, and clonal hematopoiesis.

Clonal analysis by the HUMARA assay of BM and MNBCs from 3 patients. HUMARA alleles were amplified by PCR in the absence (−) or in the presence (+) of Hpa II. The ratio of digested DNA/undigested DNA allows to correct for the potential preferential amplification of one allele over the other that occurs frequently. Shadow bands result from slippage of DNA polymerase during PCR amplification. In patient no. 68, both the pre-ABMT BM sample (BM-PRE) and the last available BM (BM-LAST) showed balanced methylation patterns, consistent with polyclonal hematopoiesis before and after ABMT. In patient no. 59, the pre-ABMT BM sample, the last available BM sample, and the MNBC control sample showed an inbalanced methylation pattern, with the predominance of the upper allele, consistent with a skewed XIP. In patient no. 27, the pre-ABMT BM sample showed a balanced methylation pattern (polyclonal hematopoiesis), but subsequent BM samples obtained after ABMT (BM-1 and BM-2) showed a progressive predominance of the upper allele. Thess results are consistent with the development of clonal hematopoiesis after ABMT. See text for definitions of skewed XIP, polyclonal hematopoeisis, and clonal hematopoiesis.

Predictive Value of the Clonality Assay for the Development of t-MDS/AML

Incidence and characteristics of t-MDS/AML.

The median clinical follow-up for this cohort of 84 patients was 32 months, with a range of 1 to 102 months. Eight patients have developed t-MDS/AML, for a crude incidence of 9.5%. By FAB classification, t-MDS/AML were classified as refractory anemia (7 cases) and refractory anemia with excess of blasts (1 case). Clonality analysis of the 8 t-MDS/AML patients was as follows: 4 patients (patients no. 23, 29, 34, and 42) had clonal hematopoiesis by HUMARA test criteria, 1 patient (patient no. 2) had skewed XIP, 2 patients (patients no. 35 and 41) had polyclonal hematopoiesis, and 1 patient was homozygous for the HUMARA locus. However, in 1 of the 2 polyclonal patients who developed t-MDS, the last sample available for analysis was a BM from 20 months before diagnosis of MDS; therefore, clonal evolution during this time interval cannot be excluded. The serial clonality ratios of the seven informative patients are described below.

Patient no. 34 had clonal hematopoiesis at the time of ABMT (BM ratio = 4.9; MNBC ratio = 2). Cytogenetic analysis was normal before ABMT, but 7 months later, an abnormal clone with a del(13) (q12q14) was detected in 4 of 7 metaphases. This clone was present in 19 of 20 metaphases 15 months after ABMT, when a diagnosis of t-MDS/AML was made. This patient presents a persistent severe transfusion-dependent pancytopenia more than 1 year after transplantation, and her last clonality ratio was 16.5.

Patient no. 42 has been described previously33 and had polyclonal hematopoiesis before ABMT (BM ratio = 1.2) and then developed clonal hematopoiesis 14 months later (BM ratio = 5.8). Seven months after clonality was detected, t-MDS was diagnosed with trilineage BM dysplasia and monosomy 7 in 16 of 18 metaphases. At that time, t-MDS of the RA type was diagnosed. One year after the diagnosis of RA, her BM clonality ratio was 14.

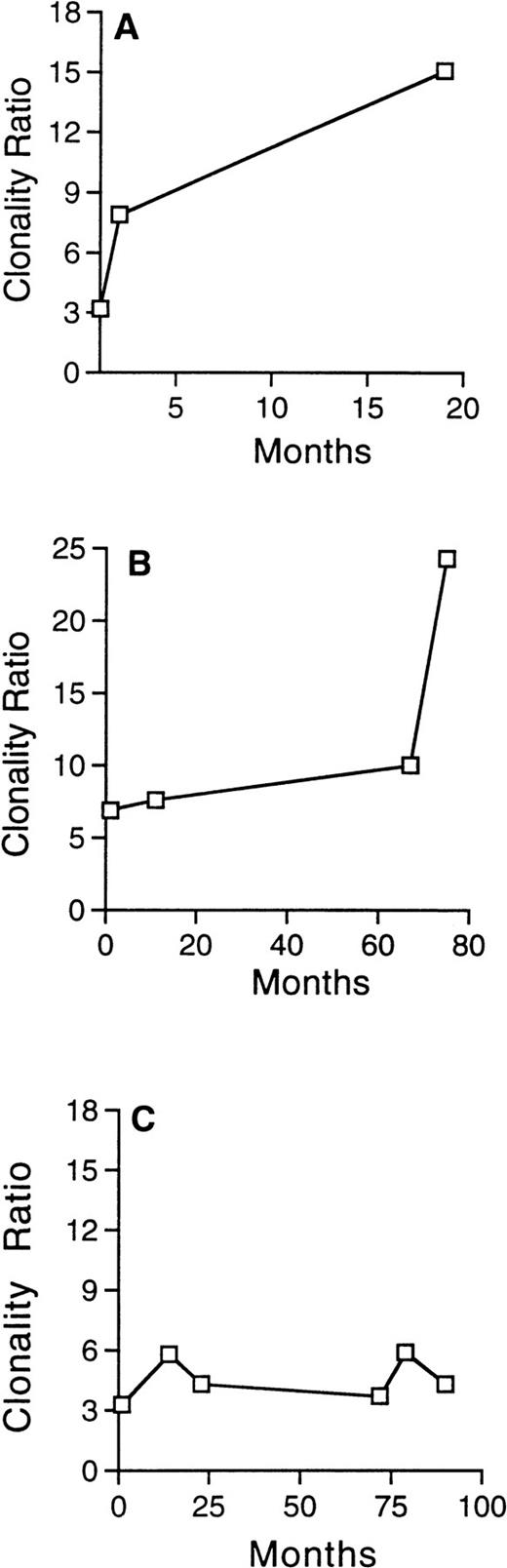

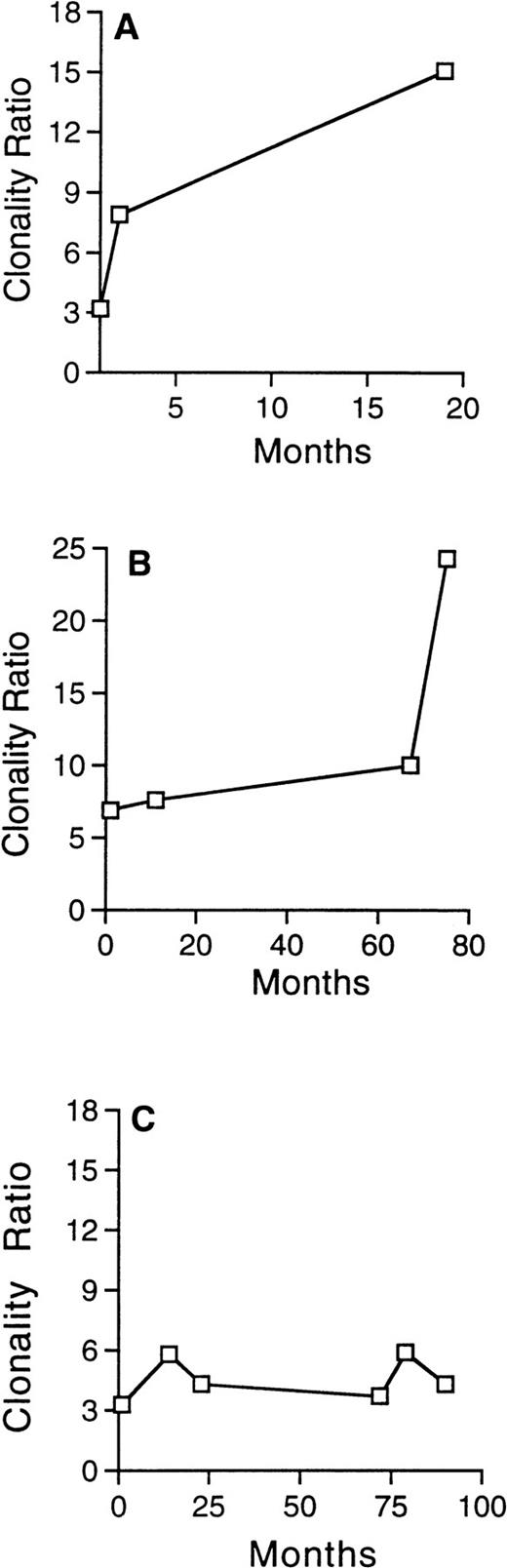

Patient no. 29 had skewed XIP before ABMT, with a BM ratio of 3.2 (MNBC ratio = 9.1). Nineteen months later, her BM ratio increased to 15.1, diagnostic of clonal hematopoiesis, but without morphologic evidence of BM dysplasia. Concomittently, cytogenetic analysis showed the presence of del(7) (q11q34) in 11 of 22 metaphases associated with the persistence of severe transfusion-dependent pancytopenia, and a diagnosis of t-MDS was made. The difference between the BM and the MNBC ratios is puzzling in this case. There are several possible explanations, including (1) the observed differences are related to a clonal population of cells in the BM; (2) because peripheral MNBCs are composed primarily of T lymphocytes, the difference observed is related to the stochastic depletion of stem cells in the BM compared with longer-lived T cells in the peripheral blood; or (3) increased variance in the assay with severe skewed XIP related to signal to noise ratio in the underrepresented allele.

Patient no. 23 had skewed XIP at the time of ABMT, with a BM ratio of 6.9. Subsequently, the BM ratio increased to 7.6, then to 10, and finally to 24.3, diagnostic of clonal hematopoiesis. At that time, the BM was consistent with t-MDS, refractory anemia with excess of blasts (RAEB) subtype. Cytogenetic analysis was normal.

Patient no. 2 had skewed XIP before ABMT (BM ratio = 3.3; MNBC ratio = 3.8) and developed t-MDS 3 years after transplantation, with hypocellular BM associated with del(7) (p13p21) in 18 of 18 metaphases. There was no significant change in her clonality ratios over time in this patient, as seen in Fig 3C, suggesting that clonality analysis may be less sensitive in patients with skewed XIP.

Evolution of the clonality ratio in 3 patients with skewed XIP before ABMT, who subsequently developed t-MDS/AML. The progressive and significant increase of the clonality ratio, detected in serial analysis in patient no. 29 (A) and in patient no. 23 (B), attest to the clonal evolution. In contrast, no significant change is detected in the clonality ratio of patient no. 2 (C), despite development of t-MDS/AML 36 months after ABMT.

Evolution of the clonality ratio in 3 patients with skewed XIP before ABMT, who subsequently developed t-MDS/AML. The progressive and significant increase of the clonality ratio, detected in serial analysis in patient no. 29 (A) and in patient no. 23 (B), attest to the clonal evolution. In contrast, no significant change is detected in the clonality ratio of patient no. 2 (C), despite development of t-MDS/AML 36 months after ABMT.

Two of 53 patients with polyclonal hematopoiesis developed t-MDS/AML. In patient no. 41, polyclonal hematopoiesis persisted at the time of diagnosis of t-MDS (RA subtype) when monosomy 7 was detected in 9 of 27 metaphases. These data are consistent with published reports34 35 that a subset of MDS patients have residual polyclonal BM cells at the time of diagnosis, presumably reflecting chimerism between normal progenitors and MDS cells. Patient no. 35 had polyclonal hematopoiesis 20 months before a diagnosis of t-MDS (RA), but no samples were available to monitor clonal evolution during this time period.

Outcome of clonal patients transplanted before 1995.

Characteristics of the 10 patients with clonal hematopoiesis who were transplanted before 1995 are listed in Table 2. The 4 clonal patients that developed t-MDS/AML have been described above. Two of 6 clonal patients that did not develop t-MDS/AML had clinical, hematological, and/or cytogenetic status suggestive of t-MDS. However, the lack of frank BM dysplastic features precluded the diagnosis of t-MDS/AML in these 2 patients, as described below.

Patient no. 5 had polyclonal hematopoiesis at the time of ABMT (BM = 2.1). Nine months after ABMT, clonal hematopoiesis was documented (BM = 4.7) concomitant with del(7) (q22q36) in 16 of 28 cells, and several months later this clone constituted 32 of 32 metaphases. Three years after ABMT, the patient had mild leukopenia without BM dysplasia, persistent clonal hematopoiesis, and cytogenetic analysis showing 2 different abnormal clones, del(13)(q11q14) in 7 of 14 metaphases and del(7) (q22q36) in 1 of 14.

Patient no. 52 had skewed XIP before ABMT (BM = 6.4; MNBC = 4.6) and, 4 years later, the BM ratio decreased to 1.4, representing a decrease in the clonal population of cells from 86% to 40% The shift from a skewed XIP to a polyclonal ratio is consistent with a shift to clonal hematopoiesis with the statistically rare event of the clonal population arising from a cell with the underrepresented XIP. This patient had relapsed NHL, with severe transfusion-dependent thrombocytopenia and del(13) (q12q14) in 15 of 28 metaphases. Although these findings are consistent with a diagnosis of t-MDS, BM morphology lacked the characteristic dysplasia necessary for diagnosis. These data are also consistent with detection of the clonal NHL in the BM.

Clonal hematopoiesis as defined by the HUMARA assay is predictive of an outcome of t-MDS/AML.

t-MDS/AML developed in 2 of 53 patients with polyclonal hematopoiesis and in 4 of 10 patients with clonal hematopoiesis, as defined by the HUMARA assay. Incidence of t-MDS/AML between the clonal and the polyclonal population was compared with the Fisher's exact test, which showed that development of t-MDS/AML was strongly associated with the presence of clonal hematopoiesis (P = .004).

The relationship between clonal hematopoiesis and cytogenetics.

Thirty-seven of 78 patients had cytogenetic analysis performed after ABMT; of these 37, 16 had the presence of an abnormal clone (Table 3). Cytogenetics were obtained in 7 of the 10 patients with clonal hematopoiesis. Of these 7 patients, 5 of 7 (71%) had an abnormal clone, which in each case was present in greater than 50% of metaphases, and in 4 the abnormal clone involved chromosomes 7 and 13, as seen in t-MDS.36 37 In contrast, only 9 of 28 (32%) non-MDS patients with nonclonal hematopoiesis had abnormal cytogenetics, and in only 1 of 10 was the abnormal clone present in more than 50% of metaphases. Compared with nonclonal non-MDS patients, MDS/clonal patients were associated with abnormal cytogenetic results by the Fisher's exact test (P = .02). Furthermore, when abnormal cytogenetics were present, MDS/clonal patients were most likely to have a clone comprising ≥50% metaphases compared with nonclonal non-MDS patients (P = .001).

DISCUSSION

We report that clonal hematopoiesis, defined by the HUMARA assay, is present in a significant number of NHL patients before ABMT (3%). If prospective studies confirm that clonal hematopoiesis predicts t-MDS/AML, alternative therapies other than ABMT should be considered in these patients, including the withholding of intensive therapy in low/intermediate-grade lymphoma and allogeneic bone marrow transplant in relapsed NHL patients. Clonal hematopoiesis in this group of patients must result from previous antilymphoma therapy. Most patients who developed clonal hematopoiesis did so after ABMT (9/10). This could suggest an important role of the conditioning regimen and/or the reinfusion of damaged stem cells in the pathogenesis of clonal hematopoiesis and t-MDS/AML. In these patients, we cannot assess with our assay the risk of t-MDS/AML before ABMT. Altogether, 13.5% (10/78) patients developed clonal hematopoiesis at some point during their course, which is in accordance with the previously described incidence of t-MDS/AML in this patient population.12 In this retrospective analysis, clonal hematopoiesis, detected with the X-inactivation–based clonality assay at the HUMARA locus, was predictive of the development of t-MDS/AML (P = .004).

t-MDS/AML developed in 4 of 10 patients with clonal hematopoiesis, as defined by the HUMARA assay, transplanted before 1995. In 3 of 4 patients, the HUMARA assay would have predicted this complication 7, 13, and 15 months before the diagnosis, respectively. However, t-MDS/AML could not be predicted in 1 patient with skewed XIP who developed t-MDS/AML without significant change in her BM ratio over time (Fig 3C). Similarly, despite polyclonal hematopoiesis, 2 patients subsequently developed t-MDS/AML. In the first case, we cannot exclude a shift to clonal hematopoiesis between the time of our last analysis and the diagnosis of t-MDS/AML (20 months). However, in the second case, polyclonal hematopoiesis was present at the time of t-MDS/AML, illustrating that polyclonal hematopoiesis can persist in some cases of MDS. The interpretation of clonality assays in patients transplanted for lymphoma is also potentially complicated by the possible recurrence of the primary disease in the BM and/or peripheral blood, and the assay may have less usefulness and less clinical relevance in this context. Furthermore, X-inactivation assays are not minimal residual disease assays. The HUMARA assay, which requires determination of allelic ratios, is insensitive to the presence of less than 10% clonal cells in a polyclonal background. Therefore, the assay may lack sensitivity for detection of early clonal hematopoiesis. However, when clonal hematopoiesis is detectable with this assay, there must be a substantial proportion of cells (>10%) present with acquired mutation conferring proliferative advantage. Therefore, although not sensitive, the assay is likely to be highly specific, and, as demontrated in this study, has a high predictive value for development of t-MDS/AML. In addition, the use of MNBC or T-cell controls for skewed XIP may allow for the more accurate assessment of patients with clonality ratios less than 3:1.

The presence of an abnormal clone in cytogenetic analysis is not a rare finding after ABMT for lymphoma, but its significance remains to be determined. Traweek et al38 reported a risk of developing clonal cytogenetic abnormalities typical of t-MDS of 9% at 3 years, with only 5 of 10 patients with an abnormal clone having developed t-MDS. Stone et al12 found that 50% of sporadically tested posttransplant hematologically normal patients harbor clonal karyotypic abnormalities. Although we cannot make any definitive statements on the relationship between clonality and cytogenetics from this study, 5 of 7 patients with clonal hematopoiesis who had cytogenetic analysis had a clonal karyotypic abnormality. This clone constituted 50% or more of metaphases analyzed in all 5 patients with clonal hematopoieisis by the HUMARA assay, whereas this was the case in only 1 of 10 nonclonal non-MDS patients with a clonal karyotypic abnormality.

Skewed XIP is a potential limitation in any study using X-inactivation–based clonality analysis. In this study, 24 of 104 patients had a skewed BM pattern and 21 were confirmed to have skewed XIP with MNBC control. Clonality analysis is less sensitive in an individual with skewed XIP, because it is necessary to assess further skewing to detect clonal evolution. Nevertheless, clonal evolution can be determined in patients with skewed XIP when a progressive and significant increase of the dominant allele is detected from serial analysis,20 as in the case of patients no. 23 and 29 (Fig3). A decrease in the relative intensity of the dominant allele in a patient with skewed XIP can also be diagnostic of clonal evolution.39 For example, patient no. 52, who had skewed XIP before ABMT, developed an apparently polyclonal ratio 4 years later. This is thought to be the consequence of a somatic mutation conferring a proliferative advantage occurring in a cell with the nondominant allele. In this case, an individual polyclonal ratio could have been misinterpreted as polyclonal hematopoiesis, whereas it in fact represents the emergence of a clone derived from a cell not expressing the predominant allele, a statistically infrequent event. These examples emphasize the value of serial analysis for the detection and interpretation of a clonal shift in patients with skewed XIP. Similarly, the increase of a ratio in serial samples from, eg, 1.2 to 2.8 would not meet conventional criteria for clonal hematopoiesis.40 However, the increasing ratio may well be indicative of the presence of a clonal population of cells (from 9% to 47%). Prospective studies with careful follow-up are needed to address this question to set criteria for diagnosing a clonal shift when progressive changes in clonality ratios are detected in sequential samples.

Clonality analysis is a promising method to detect patients at risk for t-MDS/AML. The analysis may have value not only in patients with NHL undergoing ABMT, but also in patients being treated with intensive therapy for Hodgkin's disease, breast cancer, and other solid tumors. A potential limitation of this technique is skewed XIP, representing either constitutional excessive Lyonization or acquired skewing, although careful analysis of serial samples can demonstrate a shift to clonal hematopoiesis in some of these patients. ABMT may be relatively contraindicated in the cohort of patients with clonal hematopoiesis before ABMT, because this retrospective study indicates that clonality, as detected by an X-inactivation assay, is predictive of the development of t-MDS/AML. However, prospective studies with large number of patients are needed to confirm that clonal hematopoiesis predicts t-MDS/AML. These data emphasize the importance of performing ABMT on monitored protocols until these questions are resolved.

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant No. 1 PO1 CA 6696-01A1, by Leukemia Society of America Grant No. 6081-96, and by a Swiss National Science Foundation Grant (to S.M.-P). D.G.G. is the Stephen Birnbaum Scholar of the Leukemia Society of America and is an Assistant Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Address reprint requests to D. Gary Gilliland, MD, PhD, Brigham and Women's Hospital, HIM 421, 4 Blackfan Circle, Boston, MA 02115.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

![Fig. 1. Clonality assay of the HUMARA gene. (A) HUMARA locus on X chromosome. The first exon of the human androgen receptor gene contains a highly polymorphic CAG repeat with more than 20 different alleles and a heterozygosity frequency of 90%. One hundred base pairs 5′ to the (CAG)n lies a site of differential methylation between Xa (X active) and Xi (X inactive). The HUMARA assay has reliable methylation patterns that have been documented using an androgen receptor expression assay at the same locus. Within the differential methylation site are 2 restriction sites for the methylation sensitive restriction endonuclease Hpa II. Hpa II will cleave unmethylated, active X alleles, precluding amplification of these alleles by PCR primers 1 and 2. (B) The HUMARA clonality assay. DNA is digested with Hpa II and amplified by PCR using 32P end-labeled primers. In a polyclonal population of cells (b), both the maternal (M) and paternal (P) X alleles (X inactive) will be amplified and discriminated as two bands of different molecular weight on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel by the variable CAG repeat. In contrast, for a clonal population of cells (a and c), in which all cells are derived from a single common progenitor, only the maternal or paternal allele (X inactive) will be amplified, giving a single band. In accordance with published literature, patients are considered to have clonal hematopoiesis if the corrected allelic ratio (Cr) is greater than 3:1. Ratios between 1:1 and 3:1 (ie, between 1 and 3) are considered to represent polyclonal hematopoiesis ([▪] paternal allele; [□] maternal allele; large open box denotes longer CAG expansion associated with paternal allele; small hatched box denotes shorter CAG expansion associated with maternal allele; slash mark indicates active unmethylated allele cleaved by Hpa II).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/91/12/10.1182_blood.v91.12.4496/4/m_blod41214001x.jpeg?Expires=1763546955&Signature=iMZDAviNE2i3HxqD8w3GM~BQjCx1p1~LBoR4UvWs1UzvCQDBEnyR69ym4VcV7Elv~gavJJaXMQlepLP2Ut0dZ1peC0bvl5JP2OydBgLHZrXyjmeOa02g~2K3KK04drYLyEVcG9bAsn4K2i6MsAmttserhYJ3AoUmlfYl5d4k-vYSDmqRqgMVnIEaS~aMmfUBay8DlR4WvHQ0laPeLm9siluIHGVByejb5zUIsaon9vGDHhiW2pSvPy6-Srjl-oOtvDOmVzascochvs51RCOy4L5YSODshPPLfpLeKlZxk1bDLXTWVHM5PO7-YY1U7N1D-4-M6vgwKrpYK55~Iyje6Q__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 1. Clonality assay of the HUMARA gene. (A) HUMARA locus on X chromosome. The first exon of the human androgen receptor gene contains a highly polymorphic CAG repeat with more than 20 different alleles and a heterozygosity frequency of 90%. One hundred base pairs 5′ to the (CAG)n lies a site of differential methylation between Xa (X active) and Xi (X inactive). The HUMARA assay has reliable methylation patterns that have been documented using an androgen receptor expression assay at the same locus. Within the differential methylation site are 2 restriction sites for the methylation sensitive restriction endonuclease Hpa II. Hpa II will cleave unmethylated, active X alleles, precluding amplification of these alleles by PCR primers 1 and 2. (B) The HUMARA clonality assay. DNA is digested with Hpa II and amplified by PCR using 32P end-labeled primers. In a polyclonal population of cells (b), both the maternal (M) and paternal (P) X alleles (X inactive) will be amplified and discriminated as two bands of different molecular weight on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel by the variable CAG repeat. In contrast, for a clonal population of cells (a and c), in which all cells are derived from a single common progenitor, only the maternal or paternal allele (X inactive) will be amplified, giving a single band. In accordance with published literature, patients are considered to have clonal hematopoiesis if the corrected allelic ratio (Cr) is greater than 3:1. Ratios between 1:1 and 3:1 (ie, between 1 and 3) are considered to represent polyclonal hematopoiesis ([▪] paternal allele; [□] maternal allele; large open box denotes longer CAG expansion associated with paternal allele; small hatched box denotes shorter CAG expansion associated with maternal allele; slash mark indicates active unmethylated allele cleaved by Hpa II).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/91/12/10.1182_blood.v91.12.4496/4/m_blod41214001x.jpeg?Expires=1763546956&Signature=e6-u6emZXiLXg01NH-9u40~97MyqHKYh5KeRusXmEuoahuihXiuVic0~PQ~KEPzXZTMnoc7JdJag-BE9ho7-7BCapF9H5mfRsOwUspgLHUto82OlvJye31xQsUVCVMPx2ew90emN69BCHDION~r1e61FhXFyZLOMww56tpyuxODDlbjpaO3dSjBCnfz0wZJ8s5jOeSemZ5Bls~KAKRlrXCQ5ZN2Prq8tVldNwhBSvJeReWUKRIoFdjWa~LVqAMWr6t~fTNRL3ISepxbvdj47P9TzDfzaL6YIG3pwm1wS7YaFm7DZmctqjyfd85hRacwY-QExr9Pp-sBIZy8r9BQrug__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)