Abstract

To further define the neonatal neutrophil's ability to localize to inflamed tissue compared with adult cells, we examined the neonatal neutrophil interactions with P-selectin monolayers under two conditions: (1) attachment under constant shear stress and flow and (2) detachment where cells were allowed to attach in the absence of shear stress and then shear stress is introduced and increased in step-wise increments. Cord blood and adult neutrophils had minimal interactions with unstimulated human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) at a constant shear stress of 2 dynes/cm2. There was a marked increase in the number of both neonatal and adult cells interacting (interacting cells = rolling + arresting) with HUVECs after histamine stimulation, although the neonatal value was only 40% of adult (P < .05). Neonatal neutrophils also had significantly decreased interaction with monolayers of Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells transfected with human P-selectin (CHO-P-selectin; 60% of adult values, P < .003). Of the interacting cells, there was a lower fraction of neonatal cells that rolled compared with adult cells on both stimulated HUVECs and CHO-P-selectin. That neonatal neutrophil L-selectin contributes to the diminished attachment to P-selectin is supported by the following: (1) Neonatal neutrophils had significantly diminished expression of L-selectin. (2) Anti–L-selectin monoclonal antibody reduced the number of interacting adult neutrophils to the level seen with untreated neonatal neutrophils, but had no effect on neonatal neutrophils. In contrast, L-selectin appeared to play no role in maintaining the interaction of either neonatal or adult neutrophils in the detachment assay. Once attachment occurred, the neonatal neutrophil's interaction with the P-selectin monolayer was dependent on LFA-1 and to other ligands to a lesser degree based on the following: (1) Control neonatal neutrophils had decreased rolling fraction compared with adult neutrophils, although the total number of interacting neutrophils was equal between groups. (2) Anti–LFA-1 treatment resulted in an increase in the rolling fraction of both neonatal and adult neutrophils. However, whereas the number of interacting adult neutrophils remained unchanged, the number of neonatal neutrophils decreased with increased shear stress. We speculate that this increased detachment of neonatal cells is due to differences in neutrophil ligand(s) for P-selectin.

THE LOCALIZATION OF neutrophils to vascular sites of inflammation involves several processes, including cell capture, rolling, activation, and arrest.1 This coordinated series of events is mediated by three families of adhesion receptors: selectins, integrins, and the Ig gene superfamily. Selectins, consisting of L-selectin (CD62-L) on neutrophils and E-selectin (CD62-E) and P-selectin (CD62-P) on endothelial cells, have been shown to mediate capture and rolling but not arrest of neutrophils on endothelial cells under conditions of flow.2-4 Although L-selectin is constitutively present on circulating leukocytes,5,6 P-selectin and E-selectin expression is induced by several inflammatory cytokines.7-9 The ligands for the selectins have not been fully identified, although all contain specific carbohydrate moieties, such as sialylated-fucosylated lactosamines, which are critical components for binding.10,11 One ligand for P-selectin, P-selectin-glycoligand-1 (PSGL-1), has been identified as a sialomucin; ie, it has a large number of O-linked sugar chains clustered together on the polypeptide backbone.12 It is expressed on leukocytes, including neutrophils, monocytes, lymphocytes, and eosinosphils.13-15 PSGL-1 may also serve as a ligand for E-selectin and L-selectin.16-18 The CD18 integrins, LFA-1 (CD11a/CD18, αLβ2) and Mac-1(CD11b/CD18, αMβ2), mediate arrest and transmigration, but are unable to mediate capture from the flow stream at shear rates found in the postcapillary venule (>1 dynes/cm2).19,20 Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1; CD54) is a member of the Ig gene superfamily. It is expressed constitutively on endothelial cells, although its expression increases when the endothelium is inflamed.21 ICAM-1 serves as a ligand for LFA-1 and Mac-1 and is required for leukocyte arrest and transmigration.22

The susceptibility of human neonates to localized soft tissue infections as well as systemic infections due to bacterial or fungal agents has prompted extensive investigations of neonatal host defense mechanisms. Among the most consistently observed functional abnormalities are those related to leukocyte migration.23In vivo studies using Rebuck skin windows in human neonates have provided limited data suggesting that inflammatory responses, as reflected by leukocyte exudation, may differ from those in older children and adults.24 Studies in experimental animals have been more extensive. Newborn rabbits, rats, and primates have diminished leukoctye exudation into inflamed sites compared with adult animals.25-28 The basis for this appears multifactorial and includes diminished cell deformability, decreases in f-actin polymerization, abnormalities of microtubule assembly, as well as qualitative and quantitative defects in the cell surface adhesion receptors.29

Several groups have demonstrated that the expression of Mac-1 on resting neonatal neutrophils is equal to that of adult neutrophils30-32; however, the total cell content of Mac-1 is decreased.32 In addition, neonatal neutrophils fail to upregulate Mac-1 surface expression to the same extent as adult neutrophils in response to chemotactic factor stimulation,26,30 and that which is present is functionally less active.26,30 Recently, Rebuk et al33 have reported a decrease in baseline expression of neonatal neutrophil Mac-1, but stimulated expression was equal to that of adult neutrophils. The discrepancies in these studies have not been well explained to date.33 More consistently reported is that neonatal neutrophil LFA-1 expression and function is equal to that of adult neutrophils.30,32-34 In addition, there appears to be a decreased expression of L-selectin on neonatal neutrophils.31,35 This decreased expression contributes to the diminished adherence of neonatal neutrophils to interleukin-1 (IL-1)–stimulated human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and monolayers of transfected cells expressing E-selectin under conditions of shear stress.4 35

In the current study, we sought to determine if the impairment in the neonatal neutrophil's ability to localize to inflamed tissue could also be due to decreased interaction with P-selectin. Therefore, we investigated the interaction of neonatal neutrophils with monolayers expressing P-selectin under defined hydrodynamic shear stress.35 Using a parallel plate flow system, the monolayers can support neutrophil attachment, rolling, and arrest at shear rates of 2 dynes/cm2. We provide evidence here that neonatal neutrophils have markedly decreased interactions with P-selectin monolayers compared with adult neutrophils when cells must be captured from a free-flowing stream at 2 dynes/cm2. This appears to be due in part to lower levels of neonatal neutrophil L-selectin. We also demonstrate that, of the interacting neonatal neutrophils, a lower fraction is rolling, ie, they are arrested, compared with adult neutrophils. Using a detachment assay in which neutrophils attach in the absence of shear and then shear is introduced and increased in a step-wise fashion, we demonstrate that neonatal and adult neutrophils are equally able to resist detachment with increasing shear. However, the interacting neonatal cells have a lower fraction of rolling cells than adult neutrophils. Decreased rolling (and therefore increased arrest) of neonatal neutrophils is dependent on LFA-1. If the rolling fraction is increased by treatment with anti–LFA-1 monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs), neonatal cells are less able to maintain rolling interactions compared with adult neutrophils and detach. We speculate that, under these conditions, the neonatal ligand(s) for P-selectin may be functionally impaired.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of isolated neutrophils.

Venous blood was drawn from the placental cord of normal, full-term (gestational age, 38 to 41 weeks) neonates and from the peripheral veins of healthy adult donors. All neonates were products of an uncomplicated pregnancy delivered by planned caesarean section. Mothers of these neonates received epidural anesthesia for the delivery. None of the mothers were in active labor at the time of delivery. Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minute were ≥8. Blood samples were drawn immediately after birth. Informed consent was obtained from healthy adult donors. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Experimentation at Baylor College of Medicine and St Luke's Episcopal Hospital.

Venous blood samples were anticoagulated with citrate phosphate dextrose (0.14 mL/mL blood: Abbot, North Chicago, IL) and sedimented in 6% (wt/vol in 0.87% NaCl) dextran (Spectrum Chemical, Gardena, CA) for 45 minutes at room temperature. Neonatal blood samples were diluted in Ca2+/Mg2+ free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; GIBCO Laboratories, Grand Island, NY), pH 7.4, 1:1, before sedimentation. Leukocyte-rich plasma was layered on Ficoll-Hypaque gradients and centrifuged (300g for 20 minutes at room temperature), as previously described.35 The resulting granulocyte-erythrocyte pellets were washed and resuspended in PBS containing 0.2% dextrose (DPBS) at a concentration of 1 × 107 cells/mL.

In some experiments, isolated neutrophils were activated by incubation with the chemotactic tripeptide n-formyl-methionine-leucine-phenylalanine (fMLP; 10 nmol/L; Sigma, St Louis, MO) at room temperature for 15 minutes, as previously described.4 Activation of the neutrophil results in cleavage of the portion of L-selectin distal to the cell membrane and a change in cell shape from round to bipolar.5 However, bipolar cells are at a disadvantage when compared with unstimulated spherical neutrophils for adhesion and especially rolling under conditions of flow. Therefore, at the end of fMLP incubation, the cell suspension was diluted 10-fold with DPBS, washed to remove stimulant, and incubated for an additional 15 minutes in DPBS without fMLP. The abrupt decrease in concentration of chemotactic factor causes a reversal in neutrophil shape change from bipolar to slightly ruffed and spherical.4

MoAbs.

For blocking experiments, intact antibody preparations were used. The anti–L-selectin antibody, DREG 56 (IgG1), was prepared as described and was the gift of Dr Takashi Kishimoto (Boehringer-Ingleheim Pharmaceuticals, Ridgefield, CT).36 The anti-CD11a, R7.1 (IgG1), and anti-CD18 MoAbs, R15.7 (IgG1), were prepared as described and were the gift of Dr Robert Rothlein (Boehringer-Ingleheim Pharmaceuticals).37,38 The control MoAbs, GAP8.3, an anti-CD45 (IgG1) and a nonblocking anti–LFA-1, TS2/4, were prepared from hybridoma supernatant, as was the anti-Mac-1, M1/70 (IgG2a; American Type Culture Collection [ATCC], Rockville, MD). All MoAbs directed against leukocyte adhesion markers were titered using flow cytometry (FACS-Scan; Becton Dickinson & Co, Mountain View, CA) to determine the concentration that saturated binding sites of unstimulated and stimulated cells as previously described.35 Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled goat-antimouse antibody was used as second antibody (Jackson Immuno-Research Laboratories, West Grove, PA). A panel of MoAbs against ICAM-1 were used in the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and in the static adhesion assay. These included murine antihuman ICAM-1, R6.5 (IgG2a) and CA7 (IgG1) (both provided by Dr Robert Rothlein39) murine antirat ICAM-1, 1A29 (IgG1) (kind gift of M. Miyasaka, Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science, Tokyo, Japan40); rat antimouse ICAM-1, YN-1 (IgG2b) (provided by M. Isobe, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan41); anticanine ICAM-1, CL18/1 (IgG1) and CL18/6 (IgG1).42 Control antibodies included anti–P-selectin, Cytel 1747 (PB1.3, IgG143; a gift of Dr J. Paulson, Cytel Corp, San Diego, CA); antihuman L-selectin, DREG 200 (IgG1; a gift of Dr Takashi Kishimoto36); antihuman VCAM-1, CL40 (murine IgG1)44; antihuman E-selectin, CL2/6 (murine IgG2a),45 and 7A9 (murine IgG1) and antihuman HLA-A,B,C, W6/32 (IgG2a). The latter two MoAbs were produced from hybridomas purchased from ATCC. Fab fragments of R6.5 were prepared with an ImmunoPure Fab preparation kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Anti–L-selectin MoAb, FITC-labeled Leu-8 (FITC-Leu-8, IgG2b), and anti-CD11b, phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled Leu 15 (PE-Leu15, IgG2b), as well as isotype-matched fluorescent controls were purchased from Becton Dickinson.

Preparation of monolayers.

Endothelial cells were harvested from five to eight collagenase-treated umbilical cords, pooled, and plated on fibronectin-coated (1 mL of 5 μg/mL human plasma fibronectin for 30 minutes; GIBCO) 35-mm diameter tissue culture dishes at sufficiently high density to form a confluent monolayer without cell division, as previously reported.3Monolayers were cultured in M199 (GIBCO) supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO-defined fetal bovine serum), hydrocortisone (1 μg/mL; Sigma), low molecular weight heparin (1 μg/mL; Sigma), gentamicin (25 μg/mL; Sigma), and amphotericin B (1.25 μg/mL as Fungizone; GIBCO). No growth factors were used. Cultures were maintained for 3 to 5 days at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

CHO cells expressing a phosphatidylinositol-glycan–linked form of P-selectin (CHO-P-selectin) were a gift of Dr Christine Martens (Affymax Research Institute, Palo Alto, CA).46 These cells were plated onto coverdishes or a 96-well microtiter plate and allowed to reach confluence within 3 days. For the static adhesion assay, cells were plated onto glass coverslips that had been treated with 0.1% gelatin (Sigma) for 30 minutes.

Flow cytometry.

The CD11b and L-selectin expression levels of adult and neonatal neutrophils were determined by flow cytometry using PE-Leu-15 and FITC-Leu8. As cells were prepared for infusion into the adhesion assay flow chamber, an aliquot was reserved, immediately cooled to 4°C, and labeled with the antibodies or fluorescent isotype-matched controls. The cells were washed, and the erythrocytes were lysed and fixed (BD lysing reagent; Becton Dickinson). The mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) for 5,000 particles/sample was obtained using linear detection settings. The levels of L-selectin and CD11b for each cell type for each experiment were normalized against the value of the isotype-matched control (background).

Cell surface ELISA.

The expression of ICAM-1 or an ICAM-1–like molecule on CHO cells expressing P-selectin and nontransfected cells was determined by cell surface ELISA.47 The CHO cells were plated onto a 96-well plate. After confluence was reached, the plate was washed and fixed with 0.25% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) for 15 minutes at room temperature. The cells were then blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin (Sigma) for 2 hours at room temperature and labeled in duplicate with saturating concentrations of anticanine, antihuman, antirat, and antimurine ICAM-1; antihuman VCAM-1; antihuman L-selectin; antihuman HLA; and antihuman E-selectin MoAbs for 1 hour at 25°C. Bound antibody was detected by alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat antimouse or antirat IgG (Sigma) with 1 mg/mL p-nitrophenyl phosphate disodium (Sigma) in 1 mol/L diethanolamine (Sigma; pH 9.8), containing 0.5 mmol/L MgCl2 (Sigma) as the substrate. The plates were read at 405 nm by an automatic microplate reader (Cambridge Technology, Waterford, MA).

Adhesion assay under static conditions.

A visual static adhesion assay has been described in detail previously.48 Briefly, CHO cell monolayers grown on 25-mm round glass coverslips were washed three times in PBS and immediately inserted into a modified Sykes-Moore Chamber. In selected experiments, monolayers were treated for 15 minutes with control or anti–ICAM-1 MoAbs and then rinsed. Untreated neutrophils or neutrophils treated with MoAb and/or chemotactic stimulus (10 nmol/L fMLP for 10 minutes at room temperature) were injected into the chamber and allowed to settle on to the monolayer for 500 seconds. The number of neutrophils in contact with the monolayer was determined by counting 2 to 3 high-power fields (40× objective). The chamber was then inverted for an additional 500 seconds so that only adherent cells remained attached to the monolayer. The number of cells was again counted in 3 to 10 fields. Results are expressed as the percentage of cells initially in contact with the monolayer that remained adherent per field.

Adherence assay under continuous flow: attachment assay.

Neutrophil interaction with histamine-stimulated HUVECs was assessed under continuous flow, as previously described.3,4 Briefly, primary seeded HUVECs were grown to confluence on fibronectin-coated 35-mm tissue culture dishes, rinsed in DPBS (with calcium and magnesium), mounted in parallel plate flow chambers, and perfused for 2 to 3 minutes with DPBS to remove all soluble factors. Histamine in PBS (final concentration, 10−4 mol/L; Sigma) was perfused for 10 minutes, at which point neutrophils were added to the feed line at a final concentration of 1 × 106/mL and perfusion was continued for an additional 10 minutes. The HUVECs were stimulated with histamine for the 20-minute duration of the experiment. This concentration of histamine resulted in maximal adhesion, with no effect on HUVEC monolayer confluence or neutrophil activation as determined by assessing neutrophil morphology. Neutrophils were either untreated or pretreated with MoAbs at saturating concentrations 15 minutes before being added to the feedline. fMLP-treated neutrophils were prepared as described earlier. Flow was maintained at a shear stress of approximately 2 dynes/cm2. A temperature-controlled Lucite box surrounding the microscope and flow chamber assured that all flow experiments were performed at 37°C. Interactions between neutrophils and the endothelial monolayer were observed by phase-contrast videomicroscopy (Diaphot-TMD microscope [Nikon, Inc, Garden City, NY] and CCD Video camera [Sony Corp, Park Ridge, NJ]) and quantified with a digital image processing system (Optimas; BioScan, Edmonds, WA). For each experiment, approximately 6 fields of view were recorded with a 20× objective at 7.5 minutes at 20 seconds per field. The total number of cells interacting with the monolayer were determined and referenced per square millimeter of the monolayer. For the purposes of the present study, interacting cells were defined as cells rolling at a velocity less than the flow stream plus those that were arrested. Rolling cells moved more than one cell diameter during a 1.0-second interval that was determined by time-lapsed digital subtraction techniques.4 The number of arrested cells was derived from the arithmetic difference between the number of interacting and rolling cells. Attachment assays with monolayers of CHO-P-selectin were performed essentially as described in the endothelial experiments, except that histamine perfusion was eliminated.

Adherence assay detachment under increasing shear stress.

To further characterize the neonatal neutrophil's adhesion to P-selectin, we assayed the strength of the neutrophil interaction with the monolayer in a detachment assay, as previously described.49 The number of neutrophils that remained interacting after a static incubation was quantified as shear stress was increased, giving a measure of the strength of adhesion to the monolayer. In this assay, cells were allowed to settle onto the CHO-P-selectin monolayer for 2 minutes in the absence of shear. The flow was begun (shear stress of 0.6 dynes/cm2) and then increased every 20 seconds to achieve stepwise increases in shear stress (1.4, 2.8, 12.2, and 22.1 dynes/cm2). The number of interacting cells were determined in three random fields in the final 10 seconds before the next increase in shear stress. Results are expressed as the percentage of neutrophils remaining interacting at that shear stress referenced to the number of neutrophils that had settled onto the monolayer in the absence of shear stress (percentage of settled cells remaining interacting). As in the attachment assay described above, interacting neutrophils included those that were rolling and those arrested (ie, not rolling greater than 1 cell diameter during a 1-second observation period). The rolling fraction of neutrophils at each shear stress was determined by dividing the number of rolling neutrophils by the total number interacting at that shear stress.

Statistical analyses.

Results are reported as mean ± SEM. Statistical assessments were performed as follows. The unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test was used to examine expression of adhesion molecules under different treatment conditions; as repeated testing was performed, significance was considered at P < .005. For static adhesion assay and attachment assays under flow conditions, a one-way analysis of variance (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) was performed. The probability of statistical significance between interactions of adult and neonatal neutrophils was determined by the Student-Newmann-Keuls test. Probability values less than .05 were considered significant. For detachment assays, a two-way ANOVA was performed to determine the significance of increasing shear stress on the interactions of adult and neonatal neutrophils. Significance was set at P < .05.

RESULTS

Neonatal neutrophils have less interaction with monolayers expressing P-selectin.

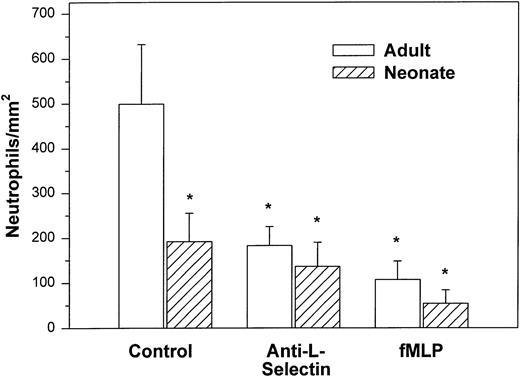

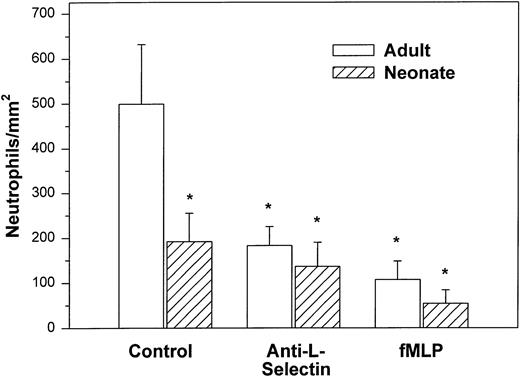

We initially examined the ability of the neonatal neutrophil to be captured by monolayers expressing P-selectin under hydrodynamic shear stress of 2 dynes/cm2. Both adult and neonatal neutrophils had minimal interaction with unstimulated HUVECs (9.8 ± 2.9v 29.3 ± 18.2 cells/mm2, respectively). Histamine causes rapid mobilization of P-selectin from the Weibel-Palade bodies to the surface of the endothelial cells and markedly increases neutrophil adhesion.3,50 In the present study, as seen in Fig 1, we also demonstrated a marked increase in the number of interacting adult neutrophils (499 ± 133 cells/mm2) to histamine-stimulated HUVECs. The peak number of interacting neutrophils occurred 5 to 10 minutes after the addition of cells and 47% ± 11% of the neutrophils exhibited rolling behavior. Arrested neutrophils did not roll for the 1-second observation period. None of the arrested neutrophils migrated through the monolayer.3There was also an increase in the number of neonatal neutrophils interacting with histamine-treated HUVECs compared with nonstimulated HUVECs, although there were significantly fewer neonatal neutrophils interacting than adult neutrophils (192 ± 63 cells/mm2, P < .05, Fig 1). The percentage of neonatal neutrophils that rolled during the observation period was 27% ± 6%. Rolling velocity was similar between neonatal and adult neutrophils (adult, 36.5 ± 5.8 μm/sec; neonate, 31.8 ± 5.4 μm/sec).

Adult (□) and neonatal (▨) neutrophil adhesion to HUVECs stimulated for 10 minutes with 10−4 mol/L histamine before the addition of neutrophils under shear stress of approximately 2 dynes/cm2. The total number of interacting neutrophils per square millimeter of monolayer includes both rolling and arrested cells. The number of interacting neutrophils was quantified beginning 7.5 minutes after the neutrophil suspension was introduced into the chamber. Neutrophils were left untreated (control) or were preincubated with anti–L-selectin MoAb, DREG 56 (50 μg/mL), or treated with 10 nmol/L fMLP as described. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM from 7 to 11 experiments. *P < .05 compared with adult control neutrophils.

Adult (□) and neonatal (▨) neutrophil adhesion to HUVECs stimulated for 10 minutes with 10−4 mol/L histamine before the addition of neutrophils under shear stress of approximately 2 dynes/cm2. The total number of interacting neutrophils per square millimeter of monolayer includes both rolling and arrested cells. The number of interacting neutrophils was quantified beginning 7.5 minutes after the neutrophil suspension was introduced into the chamber. Neutrophils were left untreated (control) or were preincubated with anti–L-selectin MoAb, DREG 56 (50 μg/mL), or treated with 10 nmol/L fMLP as described. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM from 7 to 11 experiments. *P < .05 compared with adult control neutrophils.

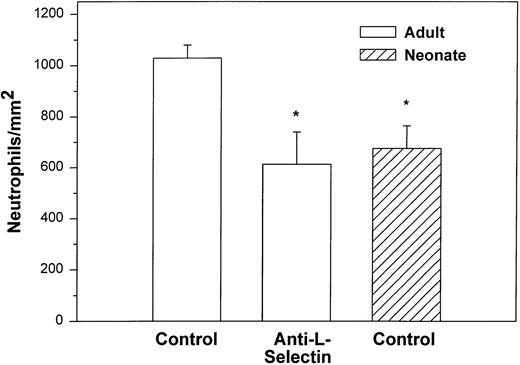

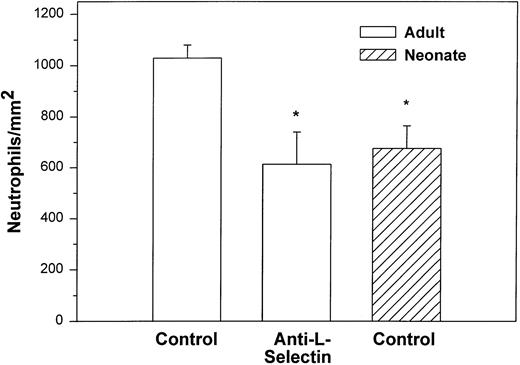

We also examined the adhesion of adult and neonatal neutrophils to confluent monolayers of CHO cells stably transfected with a phosphatidylinositol-glycan–linked form of human P-selectin (CHO-P-selectin).46 As demonstrated with histamine-stimulated HUVECs, there were significantly fewer neonatal neutrophils interacting with the CHO-P-selectin than adult neutrophils (P < .01; Fig 2). Whereas 63% ± 6% of adult neutrophils rolled, only 32% ± 8% of neonatal neutrophils did so (P < .01). Rolling velocity was less on CHO-P-selectin than on histamine-stimulated HUVECs for both neonatal and adult neutrophils, although there was no difference between the groups (neonate, 10.9 ± 1.6 μm/sec; adult, 8.6 ± 0.7 μm/sec).

Adult (□) and neonatal (▨) neutrophil adhesion on CHO cells stably transfected with human P-selectin under shear stress of approximately 2 dynes/cm2. The total number of neutrophils per square millimeter includes both rolling and arrested cells. Neutrophil treatment and analysis were performed as outlined in Fig 1. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM from 5 to 13 experiments. *P < .003 compared with adult control neutrophils.

Adult (□) and neonatal (▨) neutrophil adhesion on CHO cells stably transfected with human P-selectin under shear stress of approximately 2 dynes/cm2. The total number of neutrophils per square millimeter includes both rolling and arrested cells. Neutrophil treatment and analysis were performed as outlined in Fig 1. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM from 5 to 13 experiments. *P < .003 compared with adult control neutrophils.

Contribution of L-selectin to adult and neonatal neutrophil adhesion to P-selectin under continuous shear conditions.

We and others have published that L-selectin is important for attachment of neutrophils to P-selectin–bearing substrates.3,51 Additionally, we demonstrated that neonatal neutrophils have decreased expression of L-selectin, resulting in decreased adhesion of neonatal neutrophils to IL-1–stimulated HUVECs (which expresses both E-selectin and the L-selectin ligand35) as well as transfected cell monolayers expressing E-selectin.4 We hypothesized therefore that the decreased interaction of neonatal neutrophils with P-selectin monolayers under continuous shear conditions could at least partly be due to decreases in expression of L-selectin. Neonatal neutrophils obtained for our current studies also had significantly less L-selectin than adult neutrophils (Table 1). Neutrophil L-selectin function was inhibited by either blocking with the anti–L-selectin MoAb, DREG 56, or by stimulating with the chemotactic factor fMLP, which results in the cleavage of the extracellular portion of L-selectin.5 Incubation of either neonatal or adult neutrophils with the anti–L-selectin MoAb had no significant effect on the expression of the L-selectin epitope recognized by the MoAb, Leu8, or on the expression of Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18; Table 1). Stimulation of both neonatal and adult neutrophils with fMLP significantly decreased L-selectin and increased Mac-1 expression (P < .001v unstimulated controls for both neonatal and adult neutrophils).

Treatment with anti–L-selectin MoAb resulted in a 64% decrease in the number of adult neutrophils interacting with histamine-stimulated HUVECs (P < .05; Fig 1) and a 40% decrease in the number on CHO-P-selectin compared with untreated adult cells (P < .01; Fig 2). The number of treated adult neutrophils interacting with either histamine-stimulated HUVECs or CHO-P-selectin was equal to that of untreated neonatal neutrophils. Treatment of neonatal neutrophils with the anti–L-selectin MoAb did not decrease the number of interacting cells (Fig 1). Although there was marked loss of functional L-selectin from the surface of both neonatal and adult neutrophils with chemotactic factor stimulation (Table 1), there was no further decrease in the number of either neonatal or adult neutrophils interacting with histamine-stimulated HUVECs compared with DREG 56-treated neutrophils (Fig 1).

Neonatal neutrophils resist detachment from P-selectin with increased shear stress, but have different rolling behaviors than adult neutrophils.

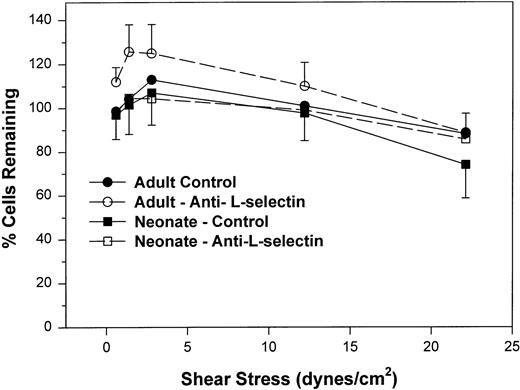

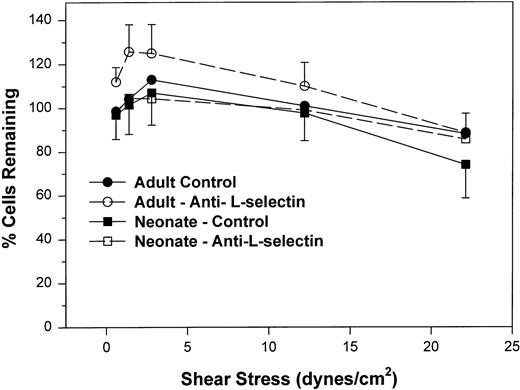

We next examined the resistance to detachment of neonatal and adult neutrophils to P-selectin substrates (see detachment assay in the Materials and Methods). In this protocol, neutrophils were allowed to settle onto the CHO-P-selectin monolayer for 2 minutes in the absence of shear stress. Shear stress was then applied in a stepwise fashion from 0.6 to 22 dynes/cm2 every 20 seconds. The number of interacting neutrophils were counted at the end of each 20-second period in three fields and referenced to the number of neutrophils that had settled onto the monolayer in the absence of shear stress (percentage of settled cells remaining interacting; Fig 3). Interacting neutrophils included those that were rolling and those arrested (ie, not rolling greater than 1 cell diameter during a 1-second observation period). When neonatal cells are allowed to attach to CHO-P-selectin before shear stress is introduced and are then subjected to increased shear stress, neonatal neutrophils had an equal percentage of settled cells that remained interacting compared with adult and were able to resist detachment to the same extent as adult neutrophils (Fig 3). There was no contribution of L-selectin to this interaction, because an anti–L-selectin MoAb had no effect on either adult or neonatal neutrophils. Thus, it appears that, once neonatal and adult neutrophils interact with CHO-P-selectin, both are equally able to resist detachment from the monolayer. This interaction is not dependent on L-selectin.

The percent of adult (○, •) and neonatal (□, ▪) neutrophils initially attached to CHO cells expressing P-selectin in the absence of shear stress that remain interacting as shear stress is then applied and increased. Neutrophils are allowed to settle onto the monolayer for 2 minutes, at which point the flow is begun and increasing shear stress is applied every 20 seconds. The number of neutrophils that remain attached in the last 10 seconds before the next step up in shear stress is compared with the number of cells that had originally settled (percentage of interacting cells remaining). Neutrophils were left untreated (•, ▪) or were preincubated with anti–L-selectin MoAb, DREG 56 (○, □). Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM from 7 to 14 experiments.

The percent of adult (○, •) and neonatal (□, ▪) neutrophils initially attached to CHO cells expressing P-selectin in the absence of shear stress that remain interacting as shear stress is then applied and increased. Neutrophils are allowed to settle onto the monolayer for 2 minutes, at which point the flow is begun and increasing shear stress is applied every 20 seconds. The number of neutrophils that remain attached in the last 10 seconds before the next step up in shear stress is compared with the number of cells that had originally settled (percentage of interacting cells remaining). Neutrophils were left untreated (•, ▪) or were preincubated with anti–L-selectin MoAb, DREG 56 (○, □). Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM from 7 to 14 experiments.

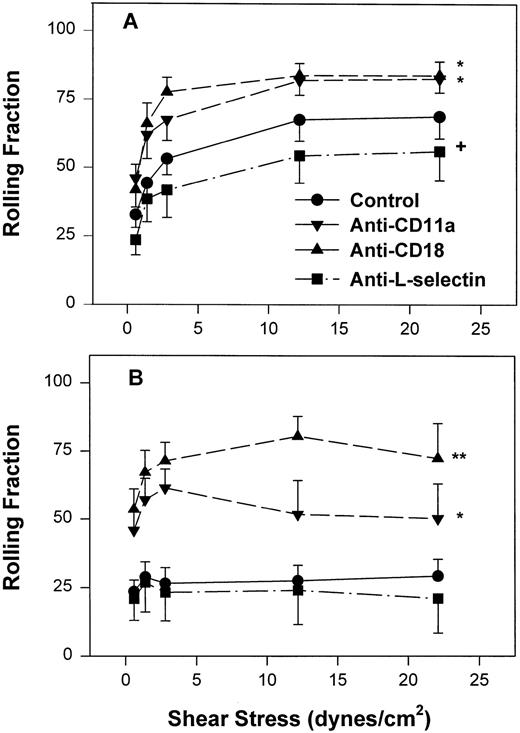

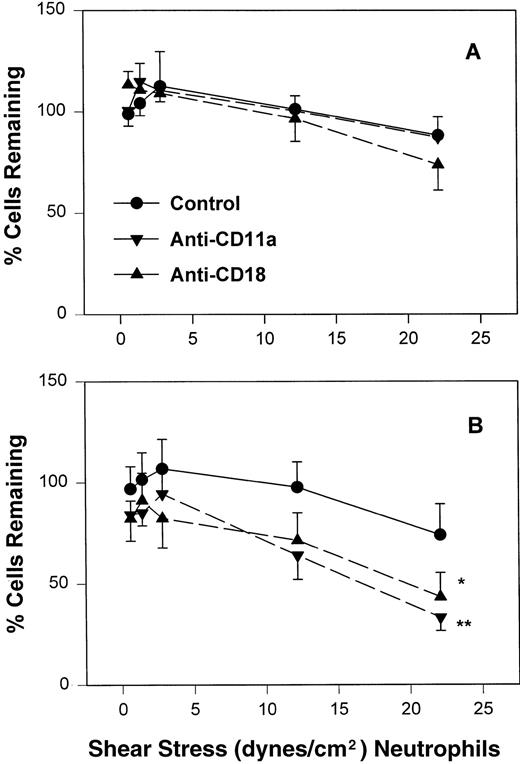

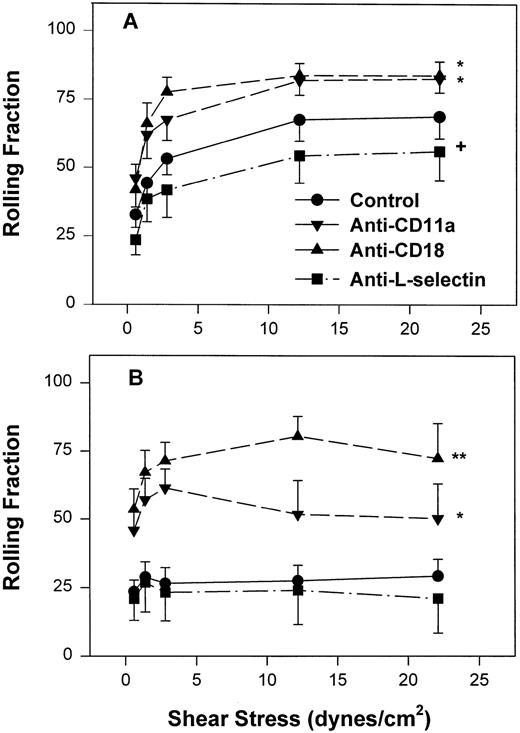

However, as with neonatal neutrophils that attached under continuous flow conditions, neonatal neutrophils demonstrated markedly different rolling behaviors compared with adult neutrophils under increasing shear conditions. The rolling fraction of neutrophils was determined by dividing the number of rolling cells by the number of interacting cells at that shear stress. As seen in Fig 4A, adult neutrophils had a significantly increased rolling fraction as shear stress increased from 0.6 dynes/cm2 (32% ± 4.7%) to 22 dynes/cm2 (69% ± 8%, P < .01, one-way ANOVA). In contrast, there was a lower fraction of neonatal neutrophils that rolled at all shear stresses. This low amount of rolling did not change with increasing shear stress (Fig 4B) and was significantly less than adult neutrophils (P < .0001, two-way ANOVA). Treatment of neonatal neutrophils with the anti–L-selectin MoAb, DREG 56, had no effect on the rolling behavior (Fig 4B). However, treatment with the anti–L-selectin MoAb resulted in a small but significant decrease in the rolling fraction of adult neutrophils (P < .05, Fig 4A).

Fraction of interacting adult (A) and neonatal (B) neutrophils that rolled on CHO-P-selectin after a 2-minute stationary contact period with increasing shear stress. Neutrophils were left untreated (•) or were preincubated with anti-CD11a MoAb, R7.1 (10 μg/mL; ▾), anti-CD18, R15.7 (10 μg/mL; ▴), or anti–L-selectin, DREG 56 (50 μg/mL; ▪). Data are expressed as the mean rolling fraction ± SEM from 7 to 14 experiments. *P < .005 compared with control neutrophils. +P < .05 compared with control. **P < .02 versus anti-CD11a–treated neutrophils.

Fraction of interacting adult (A) and neonatal (B) neutrophils that rolled on CHO-P-selectin after a 2-minute stationary contact period with increasing shear stress. Neutrophils were left untreated (•) or were preincubated with anti-CD11a MoAb, R7.1 (10 μg/mL; ▾), anti-CD18, R15.7 (10 μg/mL; ▴), or anti–L-selectin, DREG 56 (50 μg/mL; ▪). Data are expressed as the mean rolling fraction ± SEM from 7 to 14 experiments. *P < .005 compared with control neutrophils. +P < .05 compared with control. **P < .02 versus anti-CD11a–treated neutrophils.

Adhesion of neonatal and adult neutrophils to nontransfected CHO monolayers under static conditions is CD18-dependent.

We had shown previously that, under continuous shear stress, adult neutrophil arrest on histamine-stimulated HUVECs is CD18/ICAM-1–dependent.3 To avoid CD18/ICAM interactions, we therefore used CHO cells transfected with P-selectin in the previous set of experiments. Nonetheless, only 60% to 70% of interacting adult neutrophils rolled and even fewer neonatal neutrophils did so (22% to 27%) in both the attachment assay under continuous shear and the detachment assay. We speculated that the arrest of both adult and neonatal neutrophils on CHO-P-selectin could also be CD18-ICAM-1 dependent.

We sought to determine if CHO cells have an ICAM-1–like molecule using an ELISA and a panel of MoAbs directed against mouse, human, dog, and rat ICAM-1. We were unable to detect consistent cross-reactivity between any of the anti-ICAM, E-selectin, L-selectin, VCAM-1, or HLA MoAbs on either nontransfected CHO or CHO-P-selectin, although we could consistently detect increased binding of the anti-P-selectin MoAb (Cytel 1747) on the transfected cell line. We hypothesized that, if the interaction between the ICAM-like molecule on CHO and the anti-ICAM MoAbs were of a low-affinity type, this interaction would be susceptible to the vigorous washing steps of the ELISA. Therefore, we performed a static adhesion assay in which fMLP-stimulated adult neutrophils were allowed to adhere to CHO cell monolayers pretreated with anti-ICAM or control (W6/32) MoAbs that were then gently washed (3 dips in PBS) before insertion into the Sykes-Moore adhesion chamber. Treatment with anticanine ICAM (CL18/1, CL18/6) and antihuman ICAM MoAbs (R6.5 Ig, R6.5 Fab) resulted in a 30% decrease in neutrophil adhesion compared with PBS- or W6/32-treated monolayers (Table 2). If we maintained the anti-ICAM MoAb, R6.5 Fab, or control antibody, W6/32, in the reaction mix in addition to pretreating the monolayers, adhesion was decreased further (Table 2). Thus, it appears that CHO cells express a molecule(s) that can function in cell adhesion and that this adhesion can be blocked by several anti-ICAM MoAbs.

We performed a static adhesion assay with neonatal neutrophils on nontransfected CHO cell monolayers. Baseline adhesion of neonatal neutrophils treated with a control anti-CD45 (GAP8. 3) MoAb was 18% ± 5.4%; treatment with the anti-CD11a MoAb (R7.1) decreased adhesion significantly (2.7% ± 0.7%, P < .05). In contrast, adult control neutrophils (treated with anti–LFA-1 nonblocking MoAb, TS2/4) had low baseline adhesion (3.7% ± 1.0%). Adhesion of TS2/4-treated adult neutrophils was significantly increased to 13.9% ± 1.5% (P < .01) with 10 nmol/L fMLP stimulation. Stimulated adhesion could be reduced to unstimulated levels (4.9% ± 3.8%, P < .01 compared with stimulated) only with coincubation of anti–Mac-1 (M1/70) and anti–LFA-1 (R7. 1) MoAbs and not with either individually (8.5% ± 4.3% and 8.2% ± 4.2%, respectively). Under static conditions, adult neutrophils have low baseline adhesion, although adhesion can be increased with stimulation of the neutrophils. Stimulated adhesion of adult neutrophils is dependent on LFA-1 and Mac-1 and an ICAM-1–like molecule. In contrast, unstimulated neonatal neutrophils have increased adherence to nontransfected CHO cells, and this adhesion is dependent on LFA-1.

Inhibition of CD11a/CD18 results in increased neonatal neutrophil rolling fraction and increased detachment with increased shear stress.

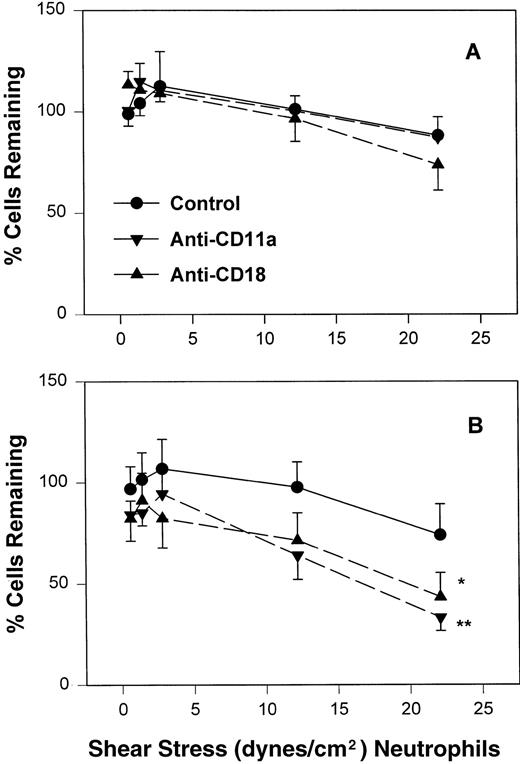

To assess the contribution of CD11a/CD18 to neonatal and adult neutrophil rolling on CHO-P-selectin, neutrophils were treated with MoAbs against either CD11a (R7.1) or the common CD18 subunit (R15.7) of LFA-1 and Mac-1. Such treatments had no effect on the expression of L-selectin or Mac-1 (Table 1). Neutrophils attached to CHO-P-selectin monolayers in the absence of shear stress, and then shear stress was initiated and increased every 20 seconds as outlined (detachment assay, see the Materials and Methods). The number of total interacting cells and those rolling were counted and the rolling fraction was determined. The fraction of rolling neutrophils significantly increased when either adult or neonatal cells were treated with either R7.1 or R15.7 compared with the age-matched controls (Fig 4A and B). Although the rolling fraction of adult neutrophils increased with inhibition of LFA-1, the percentage of cells remaining interacting as shear stress increased did not change significantly (Fig 5A). Therefore, with anti–LFA-1 treatment, adult neutrophils had increased rolling; however, these neutrophils were able to resist detachment with increasing shear stress and continued to roll. In contrast, as the rolling fraction of anti–LFA-1–treated neonatal neutrophils increased with shear stress (Fig 4B), the total number of interacting cells decreased significantly compared with untreated neonatal cells (Fig5B). Thus, the rolling neonatal neutrophils were less resistant to shear stress than adult neutrophils and had increased detachment.

The percentage of adult (A) and neonatal (B) of those initially attached to CHO-P-selectin in the absence of shear stress that remain interacting as shear stress is applied. Adult and neonatal neutrophils were treated with the anti-CD11a (▾) or anti-CD18 (▴) MoAb or left untreated (•). Data are expressed as the mean percentage of initially interacting cells remaining ± SEM from 7 to 14 experiments. *P < .05 compared with control neutrophils. **P < .005 compared with control neutrophils.

The percentage of adult (A) and neonatal (B) of those initially attached to CHO-P-selectin in the absence of shear stress that remain interacting as shear stress is applied. Adult and neonatal neutrophils were treated with the anti-CD11a (▾) or anti-CD18 (▴) MoAb or left untreated (•). Data are expressed as the mean percentage of initially interacting cells remaining ± SEM from 7 to 14 experiments. *P < .05 compared with control neutrophils. **P < .005 compared with control neutrophils.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we demonstrate that neonatal neutrophils have distinct differences compared with adult neutrophils in their interactions with monolayers expressing P-selectin. Neonatal neutrophils perfused over monolayers of P-selectin at a constant shear stress of approximately 2 dynes/cm2 demonstrated a decrease in the total number of cells that interacted with the monolayer compared with adult neutrophils. Of those cells interacting, there was a decreased fraction of neonatal neutrophils that rolled during the 1-second observation period compared with adult neutrophils. These two effects were demonstrated on both histamine-stimulated HUVECs as well as on CHO cells stably transfected with human P-selectin, although the differences in the rolling fractions was significant only on the CHO-P-selectin monolayer. When neonatal and adult neutrophils attached to CHO-P-selectin monolayers in the absence of shear stress and then shear stress was introduced, equal numbers of cells interacted with the monolayer. However, their rolling behavior again was significantly different in that neonatal neutrophils had a decreased rolling fraction compared with adult neutrophils. Treatment with anti–LFA-1 MoAbs resulted in an increase in the fraction of both neonatal and adult cells that were rolling. However, under these conditions, neonatal cells detached as shear stress increased, whereas adult neutrophils continued to roll and did not detach.

Neutrophil attachment to and rolling along the endothelia under shear flow is mediated by selectins. We have previously demonstrated that, under shear flow conditions, neonatal neutrophils have a diminished ability compared with adult neutrophils to interact with HUVECs stimulated with IL-1 (which express both E-selectin and an L-selectin ligand)35 as well as murine L cells transfected with human E-selectin.4 We and others have shown that neonatal neutrophils have diminished levels of L-selectin compared with adult neutrophils (Table 1 and previous studies33,35,52,53). This decrease in neonatal neutrophil L-selectin appears to contribute to diminished interaction with monolayers expressing the L-selectin ligand and/or E-selectin.4 35

In the present study, we demonstrate for the first time that neonatal neutrophils also have a diminished ability to interact with monolayers expressing P-selectin under continuous shear flow. That this may also be due to decreased amounts of L-selectin on neonatal neutrophils (Table 1) is supported by the finding that treatment of adult neutrophils with the anti–L-selectin MoAb decreases the number of interacting cells compared with adult control neutrophils. Furthermore, as demonstrated previously with IL-1–stimulated HUVECs35and E-selectin monolayers,4 the number of interacting anti–L-selectin–treated adult neutrophils was equal to that seen with control neonatal neutrophils (Figs 1 and 2). L-selectin has been demonstrated to be located at the tips of the microvillus of adult51 and neonatal neutrophils (M. Mariscalco and A. Burns, unpublished observations). This location of L-selectin is particularly advantageous for capturing of the neutrophils from the free-flowing stream. However, L-selectin does not contribute to continued neutrophil interaction with the P-selectin monolayer once attachment has already occurred (Fig 3). The requirement for L-selectin in the initial capture of neutrophils from the free-flowing stream to E-selectin has been described by Lawrence et al.49 However, as with this present study, once neutrophils were attached, L-selectin was not required to maintain the interaction.

The contribution of L-selectin– to P-selectin–mediated rolled has been described by us previously.3 There has been considerable controversy as to whether L-selectin can function as a ligand for P-selectin. Picker et al51 were able to inhibit by 40% to 60% neutrophil attachment to P-selectin–transfected COS cells with the anti–L-selectin MoAb, DREG 56. In contrast, Patel et al16 were unable to inhibit adult neutrophil attachment to CHO cells expressing P-selectin at continuous shear stress with DREG 56. It is unclear as to why our findings differ from those of Patel et al,16 because our experimental procedures were remarkably similar. One explanation for our findings may be that the anti–L-selectin MoAb, DREG 56, inhibits a functional domain of P-selectin. There are reports of MoAbs which cross-react with one or more selectin molecules.4,54 55 We were unable to detect binding of DREG 56 to the transfected cell line expressing P-selectin using an ELISA, although this does not rule out low-affinity interactions. Nonetheless, pretreatment of neutrophils resulted in very low concentrations of DREG 56 in the flow assays itself, making low-affinity interactions extremely unlikely.

Others have described the contribution of leukocyte-leukocyte interactions in amplifying the capture of leukocytes from a free-flowing stream.56 This interaction appears to involve PSGL-1 on one cell and L-selectin on another.17,57 It is possible that our findings reflect a decreased L-selectin–PSGL-1 interaction due to inhibition of L-selectin (treatment of adult neutrophils with DREG 56) or decreased amount of L-selectin (neonatal neutrophils). We were unable to demonstrate leukocyte-leukocyte recruitment from a review of our videotapes, although our protocol was not designed specifically to examine these interactions.17

We had demonstrated previously that neutrophils roll on histamine-stimulated HUVECs expressing P-selectin. In that study, some interacting neutrophils did not roll. This arrest was dependent on neutrophil CD18 and the ICAM-1 constitutively present on the HUVECs.3 CHO-P-selectin also supports rolling interactions.16 Unexpected, however, was the observation here that CHO cells can also support LFA-1–dependent arrest of both neonatal and adult neutrophils. Based on our findings, we suggest that CHO cells express a molecule that can function in a manner similar to ICAM-1.

Neonatal neutrophils have increased baseline adhesion to nontransfected CHO cells compared with adult neutrophils in the static adhesion assay. This adhesion could be blocked by treatment with anti–LFA-1 MoAbs. In addition, neonatal neutrophils attached to the CHO-P-selectin in the absence of shear had a significantly decreased rolling fraction compared with adult neutrophils when shear was introduced and then increased. Rolling fraction of neonatal neutrophils could be increased to that seen with adult neutrophils by treatment with anti–LFA-1 MoAbs. These findings suggest that neonatal LFA-1 is functionally more active than adult LFA-1, because, to date, there have been no reports of quantitative differences in LFA-1 expression between neonatal and adult neutrophils.30,32,33 Activation of the integrins leads to an increase in avidity for their respective ligands.58 This process has been described in lymphocytes for LFA-1 and in neutrophils for Mac-1.59-62 Only recently has there been evidence that activation of the neutrophil may also result in the affinity modulation of LFA-1.47 Is increased LFA-1 function due to the fact that resting neonatal neutrophils are activated compared with adult neutrophils? There are several studies that support this. Kjeldsen et al63 recently demonstrated the augmented release of both gelatinase and specific granules from neonatal neutrophils isolated from cord blood compared with adult neutrophils, suggesting that neonatal cord neutrophils appeared primed compared with control adult cells. Others have reported that neonatal cord neutrophils had increased oxidative burst activity.64It is unclear if the increased activity of LFA-1 can compensate for the decreased ability of neonatal neutrophils to be captured from the free-flowing stream. Our data suggest that it does not. To answer whether these observations will ultimately result in neutrophil emigration defects in vivo will require direct examination of leukocyte localization in neonatal animal models.

The rolling of neutrophils on purified P-selectin or P-selectin monolayers (CHO-P-selectin) has been reported to be dependent primarily on PSGL-1.13 16 Whereas inhibition of LFA-1–mediated arrests results in the increased rolling fraction of adult and neonatal neutrophils as shear stress increases, the number of interacting neonatal cells decrease. We propose that the decreased rolling of neonatal neutrophils is due to quantitative or qualitative differences in PSGL-1 (or other P-selectin ligands) compared with the adult. These results remain speculative until neonatal PSGL-1 function is evaluated directly.

Finally, we demonstrate that there is no statistical difference in the stimulated expression of Mac-1 on our sample of adult versus neonatal neutrophils. This may be interpreted as a discrepancy with previous findings.26,30,34,65 We suggest that this reflects instead the wide sampling variability in stimulated expression of Mac-1 in neonatal cord blood and adult samples (Table 1). That this may be so is supported by our retrospective review of the results of clinical testing of whole blood from infants (<2 months old) whom we had examined for the presence of Mac-1 and LFA-1. None of the infants had leukocyte adhesion deficiency type I or other known neutrophil defects.66 The average MFI of stimulated neutrophils stained for Mac-1 ± SD was 1,747 ± 657 for adults versus 1,042 ± 663 for infants (n = 14, P < .01; M. Mariscalco and R.N. Bennett, unpublished observations). Thus, any individual neonate can have adult levels of Mac-1. Nonetheless, in such an infant, Mac-1 function may still be depressed, because our previous study demonstrated that neonatal neutrophil Mac-1 function was decreased comparable to an adult group with equivalent levels of stimulated Mac-1 expression.34

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the nurses and physicians in the Labor and Delivery Unit of St Luke's Episcopal Hospital, without whose assistance this project would not be possible. We also thank Drs Robert Rothlein and Takashei Kishimoto for supplying antibodies, Dr Christine Martens for the P-selectin transfected cell line, and Bonnie Hughes, Jia Mei, Carol Knight, and Michelle Swarthout for their continued technical and administrative assistance.

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grant No. NIH-AI-19031.

Address reprint requests to M. Michele Mariscalco, MD, Baylor College of Medicine, CNRC, 1100 Bates, Room 6014, Houston, TX 77030-2600.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" is accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.