Abstract

To clarify the cellular origin of de novo CD5+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (CD5+ DLBL), particularly in comparison with other CD5+ B-cell neoplasms such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), we analyzed the nucleotide sequence of the Ig heavy chain variable region (IgVH) genes of de novo CD5+ DLBL cases. All 4 cases examined had extensive somatic mutations in contrast with CLL or MCL. The VH gene sequences of de novo CD5+ DLBL displayed 86.9% to 95.2% homology with the corresponding germlines, whereas those of simultaneously analyzed CLL and MCL displayed 97.6% to 100% homology. The VH family used was VH3 in 1 case, VH4 in 2 cases, and VH5 in 1 case. In 2 of 4 examined cases, the distribution of replacement and silent mutations over the complementarity determining region and framework region in the VH genes was compatible with the pattern resulting from the antigen selection. Clinically, CD5+DLBL frequently involved a variety of extranodal sites (12/13) and lymph node (11/13). Immunophenotypically, CD5+ DLBL scarcely expressed CD21 and CD23 (3/13 and 2/13, respectively). These findings indicate that de novo CD5+ DLBL cells are derived from a B-1 subset distinct from those of CLL or MCL.

HUMAN B CELLS CONSIST of two distinct subsets, B-1 cells and B-2 cells. B-1 cells are originally characterized by the expression of the CD5 antigen and are distinct from B-2 cells by anatomical localization, gene usage, function, and phenotype.1-4 B-1 cells may be developed early in ontogeny with restricted distribution on anatomical sites and often produce autoantibodies.1-5 The majority of the antibodies produced by B-1 cells are coded by relatively restricted repertories of Ig heavy chain variable region (IgVH) genes with little or no somatic mutation.2,3,4,6 However, recent analyses of the VH genes of B-1 cells presented controversial results that B-1 cells are encoded by hypermutated VH gene.7 8

CD5 is expressed in most cases of chronic lymphocytic leukemias (CLLs) and mantle cell lymphomas (MCLs) and in some cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBLs).9-11 Among the DLBLs, the CD5+ DLBLs have been recognized as Richter's syndrome as a consequence of a morphologic transformation of CLL.12However, some patients with CD5+ DLBL have no past history of lymphoproliferative disease (including CLL), and their DLBL is considered to arise de novo. We previously reported that patients with de novo CD5+ DLBL lacked cyclin D1 gene overexpression, a critical characteristic of MCL.13 Bcl-6 rearrangement, which is not seen in DLBL associated with Richter's syndrome, was exhibited in half of the cases of de novo CD5+ DLBL examined.14 These findings indicate that de novo CD5+ DLBL is distinct from other CD5+ B-cell lymphomas such as the CLLs and MCLs.

The VH genes are nonmutated in the majority cases of the CLLs and MCLs,15-17 although some exceptional cases of CLL with an isotype switch or with VH5-51(VH251) gene were reported.18 19 For the further clarification of the cellular origin of B-1 cell neoplasms, it is indispensable to know whether the VH genes of de novo CD5+ DLBL patients resemble those expressed in CLL and MCL. We therefore attempted to analyze the VH genes sequences of de novo CD5+ DLBL. We also evaluated the clinical and immunohistologic features of 13 patients with de novo CD5+ DLBL.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients/samples.

Two hundred twenty-five B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphomas of Japanese patients were selected from the lymphoma case files from the 10-year period between 1984 and 1993 in our laboratory. We studied the paraffin sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The snap-frozen specimens, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde-ethanol, were immunophenotyped using a labeled avidin-biotin alkaline phosphatase technique with the following antibodies: Leu1 (CD5), Leu4 (CD3), and CR2 (CD21) obtained from Becton Dickinson (San Jose, CA); CALLA (CD10), L26 (CD20), CD23, and anti-IgD from Dakopatts (Glostrup, Denmark); and biotinylated goat anti-human IgM, κ, λ antibodies from Tago (Burlingame, CA), as previously described.13 We diagnosed 133 DLBLs according to the REAL classification.20 Finally, 13 of 133 DLBL cases showed CD5+ phenotype (Table 1). None of these 13 patients had a past history of lymphoproliferative disorder. We obtained tissue specimens from 9 cases of these patients after their informed consent was obtained. The DNA and total RNA were extracted from the snap-frozen specimens. The cyclin D1 gene overexpression of these cases had been already investigated.13

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification.

The cDNA was synthesized from 3 μg of lymphoma tissue-derived RNA using random hexamer nucleotides and Moloney murine leukaemia virus reversed transcriptase (Bethesda Research Laboratories, Gaithersberg, MD). One-fifteenth of the cDNA of these samples was amplified using a Program Temp Control System PC-800 (ASTEC, Fukuoka, Japan) with a 50 pmol specific upstream primer corresponding to one of the six human VH family leaders (VHL1, 5′-CCATG GACTG GACCT GGAGG-3′; VHL2, 5′-ATGGA CATAC TTTGT TCCAG C-3′; VHL3, 5′-CCATG GAGTT TGGGC TGAGC-3′; VHL4, 5′-ATGAA ACACC TGTGG TTCTT-3′; VHL5, 5′-ATGGG GTCAA CCGCC ATCCT-3′; and VHL6, 5′-ATGTC TGTCT CCTTC CTCAT-3′)21 and a 40 pmol downstream primer (LJH, 5′-TGAGG AGACG GTGAC C-3′)22 designed to match the 3′ ends of the six JH segments in a 50 μL volume (10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 50 mmol/L KCl, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.001% [wt/vol] gelatin, 200 μmol/L each dNTP, and 2.5 U AmpliTaq GOLD [Perkin Elmer, Branchburg, NJ]). After 10 minutes at 95°C, a 26-cycle PCR was performed under the following conditions: a denaturation step at 94°C for 30 seconds, an annealing step at 60°C for 45 seconds, and an extension step at 72°C for 60 seconds (7 minutes in the last cycle). Fifteen microliters of the reaction product was analyzed by electrophoresis in a 4% NuSieve GTG Agarose gel (FMC, Rockland, ME) and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide.

A seminested PCR was also performed with 500 ng genomic DNA. Samples were first amplified in a final volume of 100 μL reaction buffer (10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 50 mmol/L KCl, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.001% [wt/vol] gelatin, and 200 μmol/L each dNTP) containing 2.5 U of AmpliTaq GOLD, 50 pmol of an upstream primer [FR2A, 5′-TGG(A/G)T CCG(C/A)C AG(G/C)C(T/C) (T/C)CNGG-3′]22 designed using a sequence of framework region 2 (FR2), and 40 pmol of a downstream primer (LJH). Before the 30-cycle PCR, samples were heated at 95°C for 10 minutes. The cycling protocol was a denaturation step at 96°C for 15 seconds, annealing at 60°C for 45 seconds, and extension step at 72°C for 45 seconds. Reamplification of a 1-μL aliquot (1%) of the first PCR product with 40 pmol FR2A and 60 pmol VLJH (5′-GGTGA CCAGG GTCCC TTGGC CCCAG-3′)21 was performed for 24 cycles under the following conditions: after 10 minutes at 95°C, a denaturation step at 96°C for 15 seconds, an annealing step at 63°C for 45 seconds, and an extension step at 72°C for 45 seconds (7 minutes in the last cycle) in a reaction volume of 100 μL. The final concentrations of reagents in the solution were the same as described above except for 2.0 mmol/L MgCl2. The PCR products were electrophoresed as described above.

Cloning and sequencing of PCR products.

The PCR products were purified by electrophoresis and recovered from the gel with QIAquick Gel Extraction Kits (QIAGEN, Chatsworth, CA). The recovered DNA was ligated into the pCR2.1 vector (TA cloning kit; Invitrogen, San Diego, CA), which was used to transfect INVαF′ competent cells. Using the method of blue-white selection with X-Gal (TaKaRa Biochem Co, Kyoto, Japan), 5 to 10 white colonies were picked at random and grown overnight in 2.5 mL of LB (Luria-Bertani) medium. Minipreps of plasmid were prepared from culture by alkaline lysis and purification on DNA affinity columns (QIAprep Spin Plasmid kit; QIAGEN) following the manufacturer's protocol. The double-stranded plasmid was sequenced in an automatic DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems 373; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) by using the dye terminator cycle sequencing method for usage solely with this system. For each patient, the same procedures of PCR and sequencing were performed with genomic DNA or total RNA at least two times independently.

Analysis of mutations.

The sequences obtained for each patient were compared with germline sequences using the BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool; National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD) homology search program to determine the usage of VH segments and to estimate the somatic mutations compared with the most proximal germline sequences. We then evaluated the numbers of mutations with amino acid replacement (R) or silent mutation (S) observed in the FR or complementarity determining region (CDR) of the VH gene. A sensitive binomial probability model was used to evaluate whether the observed replacement mutation in the CDR were selective.23

RESULTS

Clinical and histologic features.

Table 1 summarizes the clinical and histologic features of the 13 de novo CD5+ DLBL patients studied. Six of the 13 patients were men, and the age range was 54 to 81 years (median, 63 years). None of them showed a high titer for human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) or clinical findings of human immunodeficiency virus infections. All patients except 1 (case no. 11) showed extranodal involvement at various sites (the stomach, testis, bone marrow, spleen, liver, central nervous system, Waldeyer's ring, ileum, orbital mucosa, skin, lung, breast, kidney, and adrenal gland). Two patients (cases no. 1 and 9) presented localized extranodal disease without lymph node involvement.

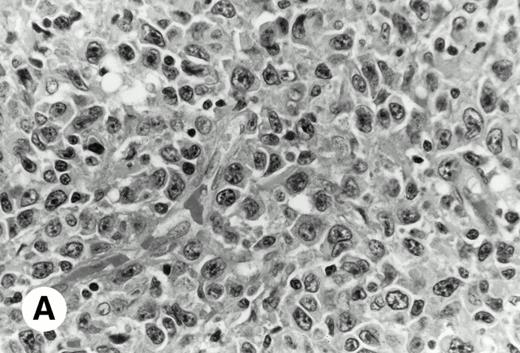

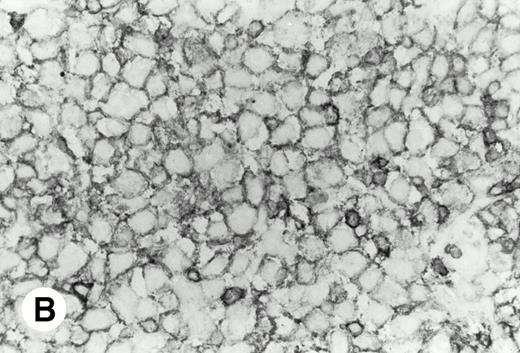

Histologically, in all cases, malignant lymphoid cells were large-sized and diffusely infiltrated. None of the samples had a proliferation center as seen in CLL or a residual germinal center as observed in MCL (Fig 1).

De novo CD5+ DLBL (case no. 1, stomach). (A) Diffuse infiltration of large neoplastic cells is observed (hematoxylin and eosin). (B) Frozen section stained for CD5 shows strong staining of atypical large cells and concomitant normal T cells.

De novo CD5+ DLBL (case no. 1, stomach). (A) Diffuse infiltration of large neoplastic cells is observed (hematoxylin and eosin). (B) Frozen section stained for CD5 shows strong staining of atypical large cells and concomitant normal T cells.

Phenotypic findings.

As shown in Table 2, in all cases, the neoplastic cells showed B-cell phenotypes bearing the pan-B–cell antigen CD20 and lacking CD10. The cells also stained for the pan-T–cell antigen CD5, but failed to stain for CD3. Ten cases were negative for CD21 and 11 cases were negative for CD23. Eleven cases expressed the IgM+/IgD− or IgM+/IgD+ phenotype, but 2 (cases no. 5 and 12) showed IgM−/IgD−.

Nucleotide sequence analysis of VH genes of tumor cells.

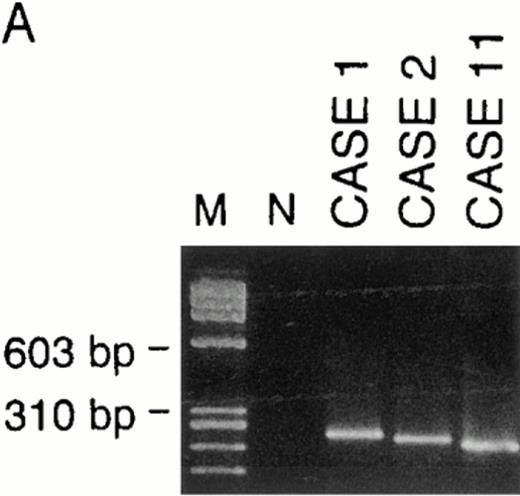

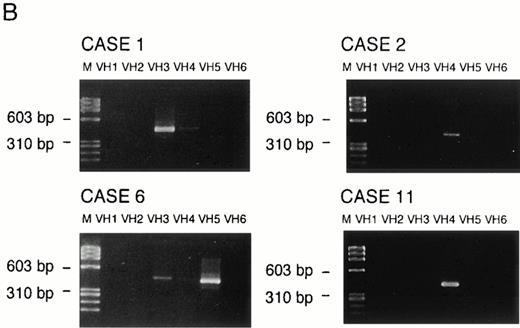

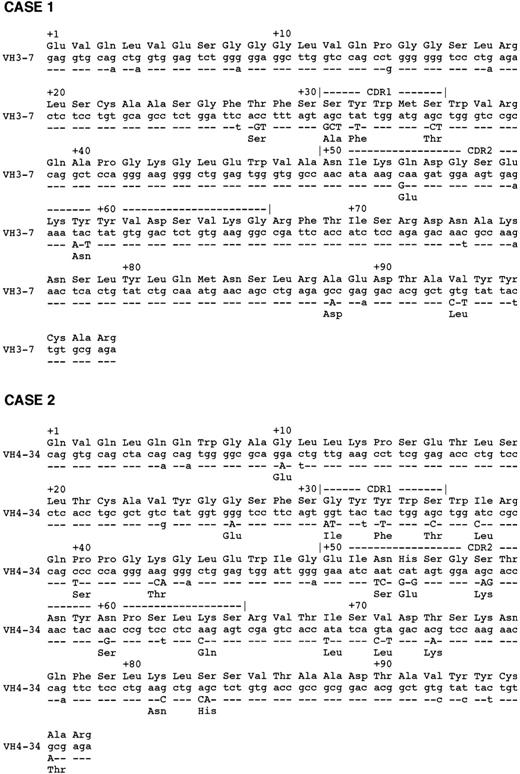

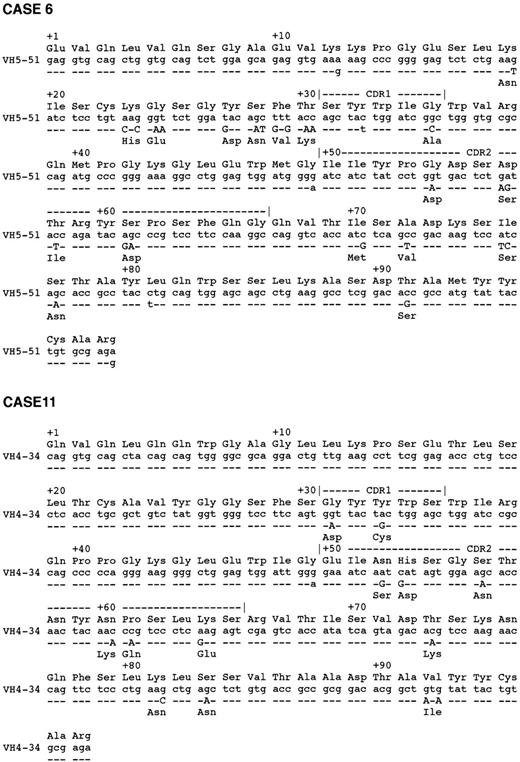

VH genes were amplified in both genomic DNA and cDNA by the use of the corresponding primer sets as described in the Materials and Methods. In cDNA, a monoclonal pattern of PCR products were obtained in 4 (cases no. 1, 2, 6, and 11) of 9 cases (cases no. 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 11, 12, and 13), whose examples are shown in Fig 2. Sequencing of those PCR products presented clonal sequences of VH segments in all of those 4 cases, as shown in Fig 3. PCR amplifications and sequencings were independently repeated two to three times, by which essentially identical clonal sequences were obtained.

Examples of PCR amplification of de novo CD5+ DLBLs with genomic DNA of cases no. 1, 2, and 11 (A) and with cDNA of cases no. 1, 2, 6, and 11 (B). PCR products were electrophoresed on a 4% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized under UV light. Lane M, molecular weight standard ◊X174/Hae III. Lane N, negative control. (A) Cases no. 1, 2, and 11 all presented monoclonal patterns whose VH genes were amplified. (B) VH1 through VH6 were amplified with corresponding VH1 to VH6 gene family-specific leader primer and a JH primer, respectively. In cases no. 1, 2, and 11, monoclonal patterns were obtained only in one of VH families, whereas in case no. 6, they were obtained in two VH families (VH3 and VH5). However, PCR products of VH3 in case no. 6 were polyclonal, as confirmed by sequencing.

Examples of PCR amplification of de novo CD5+ DLBLs with genomic DNA of cases no. 1, 2, and 11 (A) and with cDNA of cases no. 1, 2, 6, and 11 (B). PCR products were electrophoresed on a 4% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized under UV light. Lane M, molecular weight standard ◊X174/Hae III. Lane N, negative control. (A) Cases no. 1, 2, and 11 all presented monoclonal patterns whose VH genes were amplified. (B) VH1 through VH6 were amplified with corresponding VH1 to VH6 gene family-specific leader primer and a JH primer, respectively. In cases no. 1, 2, and 11, monoclonal patterns were obtained only in one of VH families, whereas in case no. 6, they were obtained in two VH families (VH3 and VH5). However, PCR products of VH3 in case no. 6 were polyclonal, as confirmed by sequencing.

Alignment of VH regions. Alignment of VH sequences of 4 cases of CD5+ DLBLs, their closest germline, and amino acids from the beginning framework region 1 to the end of framework region 3 are shown.

Alignment of VH regions. Alignment of VH sequences of 4 cases of CD5+ DLBLs, their closest germline, and amino acids from the beginning framework region 1 to the end of framework region 3 are shown.

We were also able to examine genomic DNA of 7 cases (cases no. 1, 2, 3, 4, 11, 12, and 13). Clonal PCR products were obtained in 3 cases (cases no. 1, 2, and 11), as also shown in Fig 2. Independently repeated PCR and subsequent sequencings of PCR products of cases no. 1, 2, and 11 showed clonal VH sequences exactly compatible with those obtained in the analysis of cDNA samples. Genomic DNA of case no. 6 was not available for this analysis.

Table 3 shows the comparison of the rearranged VH segments found in our samples with the most proximal germline genes reported. Three different VH families (VH 3, VH 4, and VH 5) were used, and the VH genes of two patients (cases no. 2 and 11) were closest to the VH4-34 gene.

The VH genes of de novo CD5+ DLBLs were extensively mutated, showing 86.9% to 95.2% identities to their corresponding germlines. This finding is in contrast with VH gene sequences of simultaneously examined CLL and MCL cases, in which either no or much less somatic mutations were observed as previously reported (Table 3). In all de novo CD5+ DLBL patients, the sequences of clones derived from independent bacterial plaques were essentially identical, with 1 base difference if there was any, which suggests that intraclonal variability is improbable. These reproducible observations of extensive mutations in CD5+ DLBL, in contrast with mutations in CLL and MCL samples, argue against PCR errors in the sequencing procedures.

Distribution of mutations in VH sequences.

The distribution of the somatic mutations in VH segments is shown in Table 4. In cases no. 1 and 2, the R/S ratios in the FRs were smaller than 1.5. The R/S ratios in the CDRs of cases no. 1, 2, 6, and 11 were greater than 2.9, and the probabilities of the clustering of R mutations in the CDRs were significant in cases no. 1, 2, and 11 according to the binomial model.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, all 4 de novo CD5+ DLBL cases we analyzed contained somatic mutations in the VH genes. The rearranged IgVH was detectable in 4 of 9 de novo CD5+ DLBL samples using the optimized PCR-based method. One possible explanation for this low frequency of detecting the IgVH rearrangement by PCR is the presence of high somatic diversification at sites complementary to the primers.22,24 A specific member of the VH4 family, the VH4-34 gene, was detected in 2 patients. Autoantibodies directed against the i and I carbohydrate antigen on red blood cells, a so-called cold agglutinin, are encoded by VH4-34 gene.25Idiotypes of heavy chains encoded by the VH4-34 gene are present on B cells in the mantle zone of lymph nodes and CD5+ B cells in the cord blood.26,27 A relatively high incidence of the VH4-34 gene has been reported in a minor subset of CLL with an isotype switch.18 26

The distribution of mutations in the VH regions may reflect the antigen selection of B cells. It has been suggested that an R/S ratio greater than 2.9 in the CDR accompanied by a lower ratio in the FR indicates an antigen selection of the somatically generated substitution in B cells.28 The results of the present sequence analysis of 2 de novo CD5+ DLBLs (cases no. 1 and 2) were consistent with the frequently observed mutation patterns resulting from antigen selection in B-2 cells, and cases no. 6 and 11 did not follow this pattern. In recent studies, the mutation with unusual R/S ratios was sometimes observed in human peripheral B-1 cells and in the malignant B-1 cells of patients with CLL and B-cell lymphoma with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.7,18,29 Repeated or chronic exposure to the same antigen is suggested to result in the accumulation of neutral mutations that do not affect the affinity of the Ig molecule, as is the case with allergens and autoantigens.30 31 Whether somatic mutations of B-1 cells are developed in mechanisms similar to selected mutations of B-2 cells requires further analyses.

Most cases of CLLs and MCLs might arise from B-1 cells containing nonmutated IgVH genes, with some exceptional cases of CLL. In contrast, de novo CD5+ DLBL might be derived from B-1 cells containing mutated VH genes. Phenotypically, the neoplastic cells from CLL and MCL express CD21 and/or CD23,32 whereas neoplastic cells in our de novo CD5+ DLBL cases seldom expressed either CD21 or CD23. These differences in cellular characteristics clearly indicate that de novo CD5+ DLBL are raised in B-1 cells distinct from those from which MCL and CLL arise.

The clinical characteristics of de novo CD5+ DLBL were also different from those of CLL and MCL. Patients with CLL and MCL often have an involvement of peripheral blood, bone marrow, or lymphoid organs, including lymph nodes, spleen, and tonsils. In contrast, most of the present de novo CD5+ DLBL patients showed an involvement of various extranodal sites with lymphadenopathy. These observations suggest that the precursor of the malignant cells of de novo CD5+ DLBL represents a subset of normal B-1 cells localizing at particular anatomical sites, possibly at a more differentiated stage. Alternatively, de novo CD5+ DLBL may have originated from B-1 cells of unique lineages. Although more investigation is necessary, CD5+ DLBLs might constitute a discrete subgroup that is distinguished from other DLBL derived from germinal center cells or other B-2 cells.

Supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Cancer Research (9-10) from the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Japan and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (08307003) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture.

Address reprint requests to Hiroshi Shiku, MD, The Second Department of Internal Medicine, Mie University School of Medicine, 2-174 Edobashi, Tsu 514, Japan.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.