Abstract

Lymphocytes of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected individuals undergo accelerated apoptosis in vitro, but the subsets of cells affected have not been clearly defined. This study examined the relationship between lymphocyte phenotype and apoptotic cell death in HIV-infected children by flow cytometry. Direct examination of the phenotype of apoptotic lymphocytes was accomplished using a combination of surface antigen labeling performed simultaneously with the Tdt mediated Utp nick end-labeling (TUNEL) assay. In comparison to live cells, apoptotic lymphocytes displayed an overrepresentation of CD45RO and HLA-DR expressing cells, while CD28 and CD95 expressing cells were underrepresented. Lymphocytes expressing CD4, CD8, and CD38 were equally represented in apoptotic and live populations. When percent lymphocyte apoptosis follow- ing culture was examined independently with lymphocyte subsets in fresh blood, apoptosis was negatively correlated with the percentage of CD4 cells, but not with specific CD4 T-cell subsets. Although not correlated with the percentage of total CD8 cells, apoptosis was positively correlated with specific CD8 T-cell subsets expressing CD45RO and CD95 and negatively correlated for CD8 T cells expressing CD45RA. These results provide direct evidence that a population of activated lymphocytes with the memory phenotype lacking the costimulatory molecule CD28 are especially prone to undergo apoptosis. The findings related to CD95 expression in fresh and apoptotic cells implicate Fas-dependent and Fas-independent pathways of apoptosis in HIV disease in children.

INFECTION WITH human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) results in accelerated lymphocyte apoptosis, identifiable in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) in adults1-3and children.4-6 The mechanism of HIV-induced cell death is still a subject of controversy and its role in disease pathogenesis remains unclear. An unresolved issue stems from the observation in an in vitro HIV infection system that apoptosis was limited to productively infected cells,7 while in vivo examination of lymphoid tissue suggested that uninfected bystander cells were dying.8 Apoptotic cell death was recently described in both productively infected cells and bystander cells by two different mechanisms.9 The large percentage of lymphocytes that undergo apoptosis in vitro in comparison to the low percentage of productively infected cells in peripheral lymphocytes argues in favor of bystander cell death as the major contributor to cell loss. One potential mechanism for apoptosis induction in HIV-infected individuals is attributable to signaling through the CD4 molecule10,11initiated by gp120/anti-gp120–induced cross-linking.12Another potential mechanism to explain the increased apoptosis is chronic immune activation due to the persistent nature of this viral infection. Lymphocyte progression to a memory phenotype has been associated with a decrease in expression of Bcl-213,14 and a similar phenomenon has been noted to occur in lymphocytes of HIV-infected adults.15 In concordance with these observations, Boudet et al16 described a subset of CD8 lymphocytes with low expression of Bcl-2 in conjunction with the activation markers CD45RO, HLA-DR, and CD38 in HIV seropositive donors. In addition, a significant correlation of anti-CD3–induced apoptosis with expression of CD45RO and HLA-DR has been reported in cells of HIV-infected subjects.17

Although the above findings support the notion that in vivo activated lymphocytes are the prime candidates for cell deletion in HIV-infected persons, direct proof of phenotypic identity of cells undergoing apoptosis is lacking. In this study, we used flow cytometry to directly identify the phenotypic expression of lymphocyte subsets undergoing apoptosis, as detected by the Tdt mediated Utp nick end-labeling (TUNEL) assay, in a cohort of HIV-infected children. We confirmed that both CD4 and CD8 lymphocytes undergo apoptosis, and that the dying subset is enriched for cells expressing HLA DR and CD45RO, while the live population is enriched for CD28 and CD95 expressing cells. These results provide direct evidence that apoptosis, which occurs during pediatric HIV infection, predominantly involves cellular activation together with a loss of costimulatory signaling. Concomitant studies of T-cell phenotypes in fresh blood in relation to apoptosis in cultured cells implicate Fas-dependent and Fas-independent mechanisms of cell death in this patient population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

This work is based on a cross-sectional study of HIV-infected children (n = 62) during visits to North Shore University Hospital between September 1996 and November 1997 for routine clinical testing as per Institutional Review Board approved protocols. Median age of the children in this study was 8 years (25th to 75th percentile 6 to 12 years; range, 2 months to 17 years) with a median absolute CD4 count of 388 (25th to 75th percentile 67 to 869) and a median virus load of 39,095 RNA copies/mL (25th to 75th percentile 12,020 to 87,183). None of the children in this cohort experienced an opportunistic infection during the study period.

Thirty-five children were tested at more than one time point. The time interval between testing varied from less than 1 month to 12 months with a median of 4 months. Twenty-two of these 35 children had advanced clinical and/or immunologic suppression at the time of testing, placing them in the most severe of clinical (category C) or immune (category 3) classifications. Three of the 35 children were not receiving any antiretroviral medications; all others at first testing had received several months of therapy with the longest duration being 83 months, and only four children had received less than 12 months of treatment. The treatment assignment consisted of reverse transcriptase inhibitor monotherapy in nine children and combination of two or more in 23 children. None of the children was receiving protease inhibitors at first testing, while four did at last testing.

A similar group of 27 unselected children had testing for apoptosis done at one time point only. Fourteen of these children had severe clinical disease or severe immunosuppression at the time of testing. Five subjects in this group were not receiving any treatment, one was treated with protease inhibitor, while all others were receiving combinations of two or more reverse transcriptase inhibitors. The duration of treatment was greater than 12 months for all but seven of these children.

Concurrent analysis of phenotype and apoptosis in cultured PBMC.

Blood was drawn after informed consent had been obtained and PBMC were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque (Lymphoprep; Nycomed, Oslo, Norway) density gradient centrifugation. Cells were cultured for 3 to 5 days based on a previous time course study3 in RPMI 1640 (Whittaker Bioproducts, Walkersville, MD), 10% fetal calf serum (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT), 2 mmol/L L-glutamine (Whittaker), 100 U/mL penicillin G, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Whittaker). At termination of culture, PBMC were labeled with allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated monoclonal antibody directed against either CD4, CD8, HLA DR, CD95, and with APC isotype control (Chromaprobe, Mountain View, CA) or with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated monoclonal antibody to either CD28, CD38, CD45RO, and PE isotype control (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Samples were then fixed with Permeafix reagent (Ortho, Raritan, NJ) for 40 minutes at room temperature, after which cells were incubated with the TUNEL labeling solution as per the manufacturer’s (Phoenix Flow Systems, San Diego, CA) directions. Negative and positive control cells were prepared with each experiment. Samples were stored at 4°C in the dark until flow cytometric analysis (Fig 1) on an Epics Elite ESP flow cytometer (Coulter Corp, Miami, FL). For measurement of CD95 expression on apoptotic lymphocytes following short-term culture, annexin labeling was used to detect surface phosphatidylserine. PBMC were incubated overnight and then labeled with anti-CD95 FITC (Immunotech, Westbrook, ME) and annexin biotin (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) followed by the secondary reagent streptavidin allophycocyanin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR).

Immunophenotyping of fresh PBMC.

A whole blood method was used to immunophenotype fresh PBMC using a previously described three-color panel.18 Briefly, samples were incubated with appropriate concentrations of monoclonal antibodies for 10 minutes at room temperature in the dark. Samples were lysed with a commercially available lysing reagent (Coulter lyse) and fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde until flow cytometric analysis. Monoclonal antibodies labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)/PE/peridinin chlorophyll protein (perCP) directed against the following combinations of antigens were used: CD45/CD14/CD3 to optimize the lymphocyte gate and determine purity, CD4/CD8/CD3 to quantitate helper and suppressor T-cell subsets, HLA DR/CD28/CD8 to measure activation and costimulation markers, HLA DR/CD38/CD4 or CD8 to determine levels of activation/maturation antigens, CD95/CD45RO/CD4 or CD8 to detect the apoptosis-associated marker Fas and memory cells.

Determination of virus load.

Virus load was measured by determining HIV RNA levels19 by quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction assay (Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburg, NJ). The lower limit of detection for this assay was 200 HIV RNA copies/mL.

Statistical analysis.

The percentage of apoptotic cells expressing a particular marker as compared with the percentage of live cells expressing that marker was first checked for normality of distribution by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and then compared in a paired manner using either the Student’st-test or the Wilcoxon Signed Rank test as appropriate (Sigmastat, Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA). Relationship of apoptosis to virus load and phenotypic profile of fresh PBMC was determined using Spearman’s Correlation Coefficient.

RESULTS

Characterization of phenotype of live and apoptotic cells.

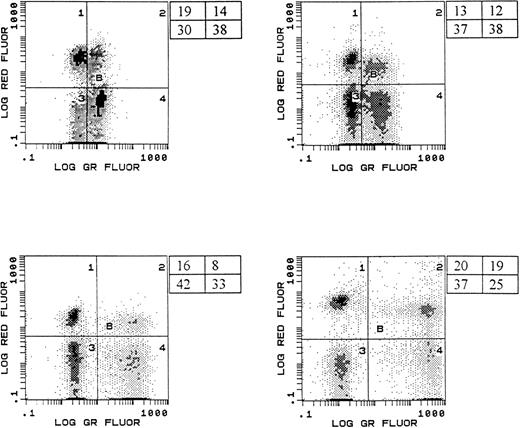

Our analysis determined whether a particular phenotype was differentially represented in either the live or dying cell population by comparing its percentage in the viable gate with its percentage in the apoptotic gate in a paired manner (Fig1). Based on the fluorescence pattern, cells that were TUNEL positive were identified as apoptotic, while those that were TUNEL negative were designated as “live” cells. CD4 and CD8 T cells were equally represented in the apoptotic and viable lymphocyte populations (Fig 2). Although the data were suggestive of an enhancement of CD38 negative cells undergoing apoptosis (median CD38+ in the live population = 68%, median CD38+ in the dead population = 48%, P = .07), there was no significant difference in the percentage of live or dead cells expressing CD38 (Fig 2). The apoptotic lymphocyte population was significantly enriched for cells expressing HLA-DR (median HLA-DR+ in the live population = 14%, median HLA-DR+ in the dead population = 44%, P < .001) and CD45RO (median CD45RO+ in the live population = 23%, median CD45RO+ in the dead population = 34%, P = .03) as compared with the viable population (Fig 2). In addition, there was a disproportionate representation of cells lacking CD28 in the apoptotic population (median CD28+ in the live population = 59%, median CD28+ in the dead population = 15%, P < .001).

Representative histograms showing simultaneous measurement of apoptosis and immunophenotype. Histograms shown represent samples from four different HIV-infected children. PBMC were labeled with anti-CD4 APC (log red fluorescence, y-axis) and then subjected to the TUNEL procedure (log green fluorescence, x-axis) to enumerate apoptotic cells. The percentage of cells in each region is shown.

Representative histograms showing simultaneous measurement of apoptosis and immunophenotype. Histograms shown represent samples from four different HIV-infected children. PBMC were labeled with anti-CD4 APC (log red fluorescence, y-axis) and then subjected to the TUNEL procedure (log green fluorescence, x-axis) to enumerate apoptotic cells. The percentage of cells in each region is shown.

Differential phenotype representation in live and apoptotic lymphocytes from HIV-infected children. Populations of live and apoptotic cells (as assessed by the TUNEL method) were examined for their expression of the indicated surface antigens. Data are presented as median with 25th and 75th percentile. Preferential selection of certain populations is indicated (*) and was calculated by comparing the percentage of a particular phenotype in the apoptotic population with the percentage in the viable population by the paired Student’st-test or the Wilcoxon Rank Sign test with P < .05 (*) considered significant.

Differential phenotype representation in live and apoptotic lymphocytes from HIV-infected children. Populations of live and apoptotic cells (as assessed by the TUNEL method) were examined for their expression of the indicated surface antigens. Data are presented as median with 25th and 75th percentile. Preferential selection of certain populations is indicated (*) and was calculated by comparing the percentage of a particular phenotype in the apoptotic population with the percentage in the viable population by the paired Student’st-test or the Wilcoxon Rank Sign test with P < .05 (*) considered significant.

In an attempt to determine the role of Fas-dependent apoptosis, the expression of CD95 was examined in the apoptotic and live populations. The percentage of CD95 expressing cells in the live population was significantly greater (34% v 22%, P = .001) than that in the apoptotic population (Fig 2). To rule out the possibility that lymphocytes may have been dying rapidly by a Fas-dependent pathway during the duration of culture, apoptosis, as detected by annexin labeling, and CD95 expression were simultaneously examined after overnight culture of PBMC. These results confirmed that CD95 was overrepresented in the live population (median CD95+ in the live population = 43%, median CD95+ in the dead population = 27%, P = .016).

Relationship of phenotype expression in fresh cells with apoptosis.

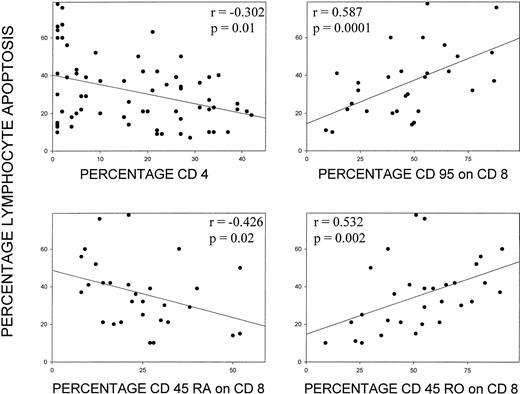

Results of an extended three-color immunophenotyping panel performed on fresh lymphocytes in a subset of patients were analyzed in relation to independent analysis of spontaneous lymphocyte apoptosis measured after 3 to 5 days culture of PBMC. The percentage of CD4 cells was negatively correlated with the percentage of lymphocytes undergoing apoptosis (r = −.302, P = .01, n = 67, Fig 3). Percentages of total T cells or of CD8+ cells did not show a correlation with apoptosis. Among specific lymphocyte subsets, no particular subset of the CD4 population showed a correlation with apoptosis. However, expression of specific markers, CD95 (r = .587, P = .0001, n = 30) and CD45RO (r = .532, P = .002, n = 30) on fresh CD8 T cells correlated with the percentage of cells undergoing apoptosis, whereas the expression of CD45RA on fresh CD8 lymphocytes (r = −.426, P = .02, n = 29) was negatively correlated with apoptosis (Fig 3).

Correlation of percent apoptosis after culture and expression of specific lymphocyte surface antigens. Apoptosis is plotted against the percentage of CD4+ cells and the percentage of CD95, CD45RA, and CD45RO+ cells in the CD8 subset measured in fresh lymphocytes. Spearman’s test was used to calculate the correlation coefficient.

Correlation of percent apoptosis after culture and expression of specific lymphocyte surface antigens. Apoptosis is plotted against the percentage of CD4+ cells and the percentage of CD95, CD45RA, and CD45RO+ cells in the CD8 subset measured in fresh lymphocytes. Spearman’s test was used to calculate the correlation coefficient.

Relationship of apoptosis to virus load, antiretroviral therapy, age, and disease stage.

Plasma HIV RNA determinations were performed in a subset of patients on the same sample used to quantify apoptosis. We compared the percentage apoptosis with virus load at one time point for each individual and found no correlation (r = .220, P = .197, n = 36). We next tested for a relationship between the change in virus load in those patients assessed at multiple time points and the corresponding change in percentage apoptosis, but were unable to detect a correlation. There was also no correlation between the change in percentage apoptosis and the change in percentage CD4 or absolute CD4 count. An additional analysis focused on patients with significant changes in virus load (defined as >0.5 log), CD4 percentage (defined as >10% CD4), or CD4 count (defined as >100 CD4 cells/μL) again showed no correlation with change in apoptosis. We also found no significant differences in the change in percentage apoptosis when children were classified into broad treatment categories (one reverse transcriptase inhibitor, two or more reverse transcriptase inhibitors, or protease inhibitor). Because T-cell numbers and subset distribution vary with age, a group of young children was compared with an older group. The subset of younger children (<72 months, n = 18) exhibited less apoptosis (median 25% v 36%, P = .046) when compared with the older children (>120 months, n = 24). The majority of the older children were classified with severe immunosuppression (17 of 24 were immune category 3), while fewer of the younger group fell into this category (7 of 18). Also of potential interest is the observation that the three children with clinically stable disease receiving no treatment who were assayed at two different time points showed absolutely no change in percentage lymphocyte apoptosis.

DISCUSSION

It is well established that accelerated lymphocyte apoptosis occurs in HIV-infected individuals, but its role in disease pathogenesis and the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. In this study, a direct identification of phenotypic expression of lymphocytes undergoing apoptosis was performed in HIV-infected children. The major finding of this study was that the lymphocytes undergoing apoptosis consist primarily of activated cells that lack CD28, suggesting that inability to receive costimulatory signaling may play a major role in this process.

The presence of activated lymphocytes expressing HLA-DR20and a shift toward the CD45RO phenotype21,22 are characteristic findings in HIV-infected persons. Studies in HIV-infected children have indicated that increased lymphocyte apoptosis is indirectly correlated with HLA-DR expression4and constant cellular differentiation from resting naive cells to primed memory cells during infection in these children increases the propensity of T lymphocytes to undergo apoptosis.23 In agreement with these findings, we observed that expression of CD45RO on CD8 cells in fresh blood correlates with induction of apoptosis. A direct examination of apoptotic cells indicated that they preferentially expressed CD45RO and HLA-DR. These results conflict with a previous report, which directly measured the phenotype of apoptotic cells in HIV-infected adults,24 including detection of the surface antigens HLA-DR and CD45RO, and concluded that lymphocyte cell death was not confined to a specific subset. These conclusions were based on analysis of a small number of adults, some of whom were in primary infection. Potentially, differences in disease stage or age of the subjects studied could explain these contradictory observations. However, the current findings demonstrate that lymphocyte activation plays a major role in apoptotic cell death during HIV infection. In fact, lack of chronic immune activation, as defined by low HLA-DR and CD45RO expression, in HIV-infected chimpanzees is correlated with resistance to apoptosis and absence of disease progression.25 These findings lead to the concept that the host response, resulting in chronic immune activation, may be the driving force behind pathogenesis of apoptosis in HIV disease. Death of activated lymphocytes has been suggested as a means of rapidly removing those cells which have served their roles in the immune response.26 Thus, this mechanism of death may represent a normal physiologic process during resolution of an infection. However, the chronic course of HIV infection may allow this process to occur in the absence of viral clearance, setting up a vicious cycle, which ultimately leads to lymphopenia, a contention supported by our observation of a correlation between loss of CD4 cells and increased apoptosis and by our finding that a group of older children, most of whom had severe disease, manifested higher levels of lymphocyte cell death than a group of younger children with less severe immune suppression.

The percentage of both CD427 and CD820 cells expressing CD38 is increased during HIV infection in adults. Expression of CD38 on CD8 cells has been implicated as an adverse prognostic marker for disease progression.28 Increases in the percentage of CD8 cells, which coexpress CD38, have also been demonstrated for a group of HIV-infected children under 2 years of age,29 as well as older infected children.30Lymphocytes expressing CD38 in children may represent two populations: (1) newly recruited immature lymphocytes and (2) mature, activated lymphocytes31; thus, our finding indicates that CD38 expression per se does not specifically detect cells primed to undergo apoptosis.

Another major feature of disease progression in HIV infection is that of a substantial increase in T cells lacking the costimulatory molecule CD28.32,33 The potential role of costimulation in protecting cells from undergoing apoptosis derives from the observations that ligation of the CD28 molecule influences long-term T-cell survival by upregulating the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-xL34 and prevents T-cell death in response to TCR stimulation, Fas cross-linking, or interleukin-2 (IL-2) withdrawal.35 Furthermore, apoptosis of CD8 T lymphocytes was shown to be related to loss of CD28 in patients with HIV36 and herpes virus37 infections. In the present study, we provide direct evidence that lymphocytes lacking CD28 preferentially undergo apoptosis in HIV-infected children. Although the basis for the progressive loss of CD28 in HIV infection is unclear, cytotoxic T-cell function has been ascribed to the CD8+CD28- subset38; preferential apoptosis of this subset thus may contribute to effector cell depletion during HIV disease progression.

The finding that CD95+ cells were enriched in the live population was unexpected. CD95 (Fas)-mediated death signals have been strongly implicated in the accelerated lymphocyte apoptosis occurring in HIV disease.39-43 Supporting this idea are the findings that the percentage of T cells expressing CD95 is increased in HIV-infected adults44 and children,5,6 and that these cells are increasingly susceptible to anti-CD95–mediated apoptosis.45 Blocking the CD95 interaction with its ligand in vitro has been reported by some investigators to reduce HIV-mediated lymphocyte apoptosis,39,42 others have been unable to do so.7,46,47 Expression of CD95 alone, however, is not sufficient for susceptibility to apoptosis, as Fas can transduce activation signals in normal T lymphocytes,48 and cells only become sensitive to Fas signaling after they have been primed after repeated antigenic stimulation49-52 or after CD4 cross-linking.11,53 54 Thus, in our study, in the direct phenotypic analysis of live and apoptotic cells, the preferential expression of CD95 in live cells may be representative of lymphocytes that had not been primed for apoptosis in vivo and possibly were further protected by a rescue signal generated through CD28. The CD95 expressing cells in the apoptotic cell population most likely represent cells that were primed for apoptosis in vivo. The association between degree of apoptosis and percentage of CD95 expressing CD8 lymphocytes in fresh blood supports the participation of Fas-dependent apoptosis contributing to the death of CD8 T cells.

The presence of CD95 negative cells in the apoptotic population suggests that Fas-independent mechanisms are also involved in exaggerated lymphocyte apoptosis seen in HIV-infected patients. Mechanisms other than Fas/Fas ligand signaling are supported by the observations that monocytes of HIV+ patients are deficient in Fas ligand55 and that blocking CD95 in patient samples47 or during in vitro infection7,46fails to inhibit apoptosis. A recent report noted that contact of uninfected CD4 T lymphocytes with HIV envelope glycoprotein expressing cells56 led to death of both infected and bystander cells not mediated by CD95. Many new death receptors have recently been described.57,58 One candidate for the death effector molecule in HIV disease is TRAIL, a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) family member, which has been implicated in HIV-induced apoptosis.59 60 However, the death effector mechanisms may differ by disease stage, intensity of the host immune response, or the lymphocyte subset involved; these factors merit further consideration.

Therapy-induced reduction in virus load has been shown to result in increases in lymphocyte cell number61,62 and reductions in virus load, including the amount of virus in lymphoid tissue.63 Although we were unable to detect a change in lymphocyte apoptosis due to the effect of concurrent antiretroviral therapies, highly active therapy has been shown to reduce the proportion of HLA-DR expressing T cells concomitant with a trend toward normalization of CD28 expression.64 The current study was not designed to address this issue, with pretreatment values for apoptosis not available for this cohort and changes to combination therapy not necessarily coinciding with cell death determinations. However, data from our laboratory from a longitudinal study of well-defined adult treatment groups suggest that reduced lymphocyte apoptosis occurs subsequent to therapy-induced reduction of virus load (S. Chavan and S. Pahwa, submitted). It is reasonable to suggest, with highly effective combination therapies now being used to treat HIV-infected children, that dramatic changes in virus load might be accompanied by decreases in lymphocyte apoptosis. In light of our findings that HIV-mediated lymphocyte apoptosis appears to be predominantly activation-induced cell death, decreased levels of antigen may serve to decelerate this process.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Regina Kowalski and Maria Marecki for technical assistance and Caroline Nubel for assistance with patient information.

Supported by Grants No. AI28281 and DA05161 from the National Institutes of Health.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Savita Pahwa, MD, North Shore University Hospital, 350 Community Dr, Manhasset, NY 11030; e-mail:spahwa@nshs.edu.