Abstract

Prognostic studies of primary cutaneous lymphomas (PCL) other than mycosis fungoides (MF) and the Sézary syndrome (SS; non–MF/SS PCL) have been mainly performed on subgroups or on small numbers of patients by using univariate analyses. Our aim was to identify independent prognostic factors in a large series of patients with non–MF/SS PCL. We evaluated 158 patients who were registered in the French Study Group on Cutaneous Lymphomas database from January 1, 1986 to March 1, 1997. Variables analyzed for prognostic value were: age; sex; type of clinical lesions; maximum diameter, location, and number of skin lesions; cutaneous distribution (ie, local, regional, or generalized); prognostic group according to the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) classification for PCL; B- or T-cell phenotype; serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level; and B symptoms. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed using a model of relative survival. Forty-nine patients (31%) died. The median relative survival time was 81 months. In univariate analysis, EORTC prognostic group, serum LDH level, B symptoms, and variables related to tumor extension (ie, distribution, maximum diameter, and number of skin lesions) were significantly associated with survival. When these variables were considered together in a multivariate analysis, EORTC prognostic group and distribution of skin lesions remained statistically significant, independent prognostic factors. This study confirms the good predictive value of the EORTC classification for PCL and shows that the distribution of skin lesions at initial evaluation is an important prognostic indicator.

PROGRESS IN therapeutic approach of Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) requires an accurate estimation of prognosis. Survival analyses have been performed in large series of patients with NHL (mainly nodal lymphomas) to identify prognostic factors.1-5 Main factors found to be associated with a poor prognosis were old age, low performance status, presence of B (systemic) symptoms, increased serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level, aggressive histological subtypes, and tumor extension. Methods to assess the tumor extension were variable and included the Ann Arbor classification, the evaluation of tumor bulk, largest diameter of tumors, and number of nodal or extranodal sites of the disease.

The evaluation of overall prognosis and prognostic factors of primary cutaneous lymphomas (PCL) other than mycosis fungoides (MF) and the Sézary syndrome (SS) met some difficulties. First, there has been confusion between PCL defined by the absence of extracutaneous disease at the time of diagnosis and nodal lymphomas presenting with skin tumors. Second, some parameters associated with a poor prognosis in nodal lymphomas, such as B symptoms or increased LDH level, are rarely present in PCL. Third, there is no consensus for evaluating the tumor extension in PCL other than MF and SS (non–MF/SS PCL). Finally, histological classification schemes used for nodal NHL seemed inadequate to classify PCL correctly. In particular, different types of PCL classified as “high-grade lymphomas,” according to the updated Kiel classification6 and to the Working Formulation,7 were found to have an indolent clinical course.8-10 These findings led the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Cutaneous Lymphoma Project Group to provide precise definitions of different subtypes of PCL, using a combination of clinical, histological, and immunophenotypic criteria, and to assign them to different prognostic groups.11,12 This resulted in a new classification for PCL whose validity was supported by a number of prognostic analyses in subgroups of PCL8,10,13-17 and by survival data of patients included in the registry of the Dutch Cutaneous Lymphoma Working group.12 The aim of our study was to test the clinical validity of the EORTC classification in an independent series of patients and to identify main prognostic factors of survival in non–MF/SS PCL.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients included in the registry of the French Study Group on Cutaneous Lymphomas (FSGCL) from January 1, 1986 to March 1, 1997 were selected for analysis if they met the following criteria: (1) diagnosis of cutaneous lymphoma other than classical MF, SS, and lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP), and (2) absence of extracutaneous disease detected by a comprehensive staging procedure at diagnosis. In each case, the diagnosis was made by an expert panel of pathologists and dermatologists during one of the quarterly meetings of the FSGCL and was based on a combination of clinical, histological, and immunophenotypical data. Classical criteria were used for the diagnosis of MF and SS.12 Clinical and histological data of all cases of MF undergoing transformation into a diffuse large-cell lymphoma18 were separately reviewed for distinction from non-MF primary cutaneous large T-cell lymphomas. Primary cutaneous pleomorphic small T-cell lymphomas were differentiated from classical MF using criteria that have been previously reported.15,17Primary cutaneous CD30-positive large T-cell lymphomas were differentiated from LyP on the basis of clinical and histopathologic data, as it was recommended.8,12,19 20 After exclusion of patients with MF, SS, and LyP, information regarding staging at diagnosis was reviewed for 204 cases. Staging procedure at diagnosis included physical examination (100% of cases), blood cell count and routine laboratory tests (100%), chest radiograph or thoracic computed tomographic (CT) scan (100%), abdominal ultrasound tomography or thoraco-abdominal CT scan (100%), and bone-marrow biopsy (93%). Nodal biopsies were only performed when enlarged lymph nodes were present (14%). Forty-one patients were excluded from further analysis because they had extracutaneous disease detected at diagnosis. Five patients were excluded because they consulted only once for initial advice in a reference center and were thereafter lost to follow-up. One hundred fifty-eight patients met the inclusion criteria and were selected for analysis.

Data collection.

Variables analyzed for prognostic value were: age at diagnosis; sex; type of clinical lesions (plaques, nodules, or tumors); anatomic site (head and neck, upper limb, anterior aspect of the trunk, posterior aspect of the trunk, or lower limb); largest diameter and number of skin lesions; cutaneous distribution (namely “local” when skin lesions involved a surface less than or equal to 100 cm2 on one anatomic site, “regional” for a surface greater than 100 cm2 on one anatomic site, and “generalized” when several anatomic sites were involved); prognostic group according to the EORTC classification (ie, indolent, intermediate, aggressive, or provisional, as defined in Table 1); B- or T-cell phenotype; serum LDH level; and B symptoms. Information regarding these variables was complete in all patients, except 8 cases for whom LDH level at diagnosis was unknown. For the classification according to diagnosis and EORTC prognostic groups, there was an agreement among pathologists to use distinctive criteria that have been proposed by Willemze et al.11 12 In particular, differentiation between CD30-positive large T-cell lymphomas and CD30-negative large T-cell lymphomas was based on the presence of more or less than 75% CD30-positive large T cells. This distinction was often easy because most CD30-negative large T-cell lymphomas had very few (<20%) CD30-positive large T cells. Differentiation between pleomorphic large T-cell lymphomas and pleomorphic small T-cell lymphomas was based on the presence of more or less than 30% large tumor cells. B-cell lymphomas composed of small centrocytes, large centrocytes, centroblasts, and/or immunoblasts were classified as follicle center-cell lymphomas, whatever the predominant cytological feature. However, those located on the legs were classified separately, as large B-cell lymphomas of the leg, if more than 50% of the neoplastic B cells were large cells. B-cell lymphomas composed of lymphocytes, lymphoplasmocytoid cells, and plasma cells with a monotypic cytoplasmic Ig were diagnosed as immunocytomas. We did not use the terms marginal zone B-cell lymphoma or mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas and classified all indolent B-cell lymphomas either as follicle center-cell lymphomas or immunocytomas, as defined above. Cases for whom a general agreement among pathologists was not achieved were reviewed using a multihead microscope and finally classified by consensus.

Follow-up.

Follow-up information was recorded until June 15, 1997 and included initial therapy, achievement of a complete response, cutaneous relapse, extracutaneous progression of the disease, and date and cause of death. Ascertainment of vital status was 96% complete on June 15, 1997. For the 6 patients (4%) lost to follow-up, the median follow-up time was 12 months (range, 3 to 26 months).

Statistical analysis.

Endpoint was death of the patient, whatever the cause. Survival duration was calculated from diagnosis to date of death or censoring. The study endpoint was June 15, 1997 for surviving patients with complete follow-up and date last known alive for the 6 patients lost to follow-up. Continuous variables were categorized for analysis as indicated in Table 2. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed with the Relsurv program,21 using a model of relative survival according to Esteve et al,22 which provides an objective estimate of the patients’ survival corrected for the effects of causes of death independent from lymphoma itself. The relative survival was estimated using a table of general mortality by age and sex in France. Factors significant at the 0.2 level in univariate analysis were included in a stepwise regression multivariate analysis.

RESULTS

One hundred patients (63%) were men and 58 (37%) were women. Age ranged from 12 to 95 years (mean: 61.5; median: 68). The other clinical characteristics of patients at diagnosis are summarized in Tables 2 and3. The distribution of cases according to diagnostic and prognostic groups of the EORTC classification is shown in Table 1. Initial therapies according to diagnosis are shown in Table3. Eighteen patients (11%) did not receive any specific treatment after initial evaluation, either because of a poor general condition or because of spontaneous regression of skin lesions. Among 108 patients (69%) who achieved a complete response, 60 (56%) had no relapse, whereas 48 (44%) experienced one or several relapses. Nodal or visceral progression of the disease was documented in 30 patients (19%).

Forty-nine patients (31%) died. The proportion of death, whatever the cause, was 6.7% among patients who achieved a complete response without relapse, 33% among patients who experienced relapses, 58% among patients who did not achieve a complete response, and 80% among patients who developed extracutaneous disease. The median relative survival time was 81 months. The 5-year overall relative survival rate was 73%.

According to the referring physician, death was related to the lymphoma in 31 of 49 cases (63%), to an unrelated cause in 9 cases (18%), and to an unknown cause in 9 cases (18%). Twenty-five of 49 patients died without evidence of extracutaneous progression of disease. The median age of these patients was 77 years. Eight of them (32%) had a large B-cell lymphoma of the leg. According to the referring physician, 40% (10 of 25) of these patients died from lymphoma, most often from cutaneous tumor progression, sepsis, or treatment-related toxicity. The others died from unrelated (8 cases) or unknown causes (7 cases).

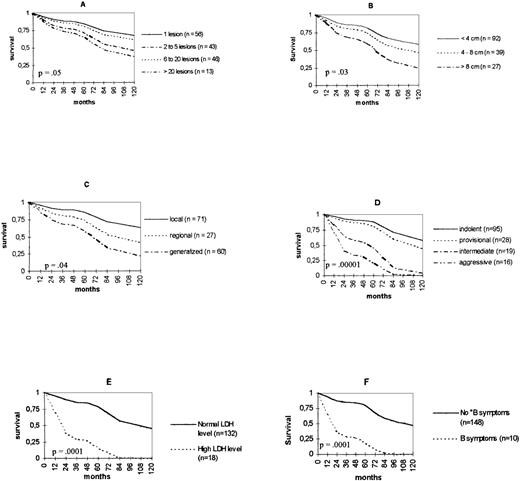

Univariate analysis of relative survival showed that the following variables were related to death from lymphoma: a high number of skin lesions (P = .05); a large maximum diameter of skin lesions (P = .03); a generalized distribution (P = .04); the classification in the EORTC prognostic groups “intermediate” or “aggressive” (P = .00001); an increased LDH level (P = .0001); and the presence of B symptoms (P = .0001). Age, sex, type of clinical lesions, anatomic site, and immunophenotype (B or T) had no significant effect on death from lymphoma. Relative survival curves for the different categories of each variable significantly related to survival are shown in Fig1. The 5-year survival rates, according to diagnosis, are shown in Table4. When multivariate analysis was performed, only the classification in the EORTC groups “intermediate” or “aggressive” (P = .0001) and a generalized distribution (P = .03) had a significant effect on death from lymphoma (Table 5).

Relative survival curves according to (A) number and (B) maximum diameter of skin lesions, (C) distribution, (D) EORTC prognostic group, (E) LDH level, and (F) B symptoms.

Relative survival curves according to (A) number and (B) maximum diameter of skin lesions, (C) distribution, (D) EORTC prognostic group, (E) LDH level, and (F) B symptoms.

DISCUSSION

Few overall prognostic studies have been performed in non–MF/SS PCL.15,23-26 The histological subtype was found to be related to survival in most,15,23,24,26 but not all25 studies. Some authors found the dissemination of cutaneous lesions to be an adverse prognostic factor,24,26whereas others did not.15,25 The serum LDH level was a significant prognostic factor in 124 of 224,26studies. Age,15,26 B- or T-cell phenotype,23,25location of the disease,26 and maximum tumor size26 were not found to have a significant effect on survival. However, these studies only included univariate analyses in about 50 patients or less and used various classification schemes and inclusion criteria. In particular, some of them included patients with extracutaneous disease detected at diagnosis,23,26 whereas others excluded patients with initial15 or even subsequent extracutaneous lesions within 324 or 625months.

In the present study, primary cutaneous lymphomas were defined by the absence of extracutaneous disease detected at the time of diagnosis. A 3- or 6-month survival time without extracutaneous progression was not required, because exclusion of patients according to events occurring within the first months after diagnosis and treatment may introduce biases in the evaluation of prognosis. Furthermore, a pragmatic approach of cutaneous lymphomas requires an evaluation of prognostic parameters before the first treatment choice.

We found the classification according to EORTC prognostic groups to be the most pertinent prognostic factor. The usefulness of this classification has been first suggested by studies that have focused attention on separate subgroups of PCL.8,10,13-17CD30-positive large T-cell lymphomas8,9 and follicle center-cell lymphomas10,14 were found to have an indolent clinical course, whereas studies of small numbers of patients with CD30-negative large T-cell lymphomas15 and large B-cell lymphomas of the leg16 suggested that they had, respectively, an aggressive and an intermediate behavior. These earlier reports were supported by survival data of a larger number of patients derived from the registry of the Dutch Cutaneous Lymphoma Working Group.12 The present study performed on an independent series of patients provides further evidence of the validity of this classification. Five-year survival rates according to diagnosis observed in this study were close to those of Dutch patients (Table 4), and slight variations may have only resulted from chance. However, some discrepancies may have been a result of variations in inclusion criteria, because the 6-month interval without extracutaneous progression was not required in our study as in Dutch survival analyses. Lastly, survival rates may be affected by the hospital selection of patients, even in a multicentric study, and population-based studies would be required for a more accurate estimation of survival in PCL. The largest difference in survival rates between French and Dutch cases concerns pleomorphic small T-cell lymphomas (Table 4). Dutch data suggests an intermediate prognosis, whereas the present report shows a more indolent clinical course. However, only 18 Dutch and 27 French cases were included in these analyses. Further studies are required to better evaluate the prognosis of this rare subtype of PCL.

A generalized distribution of skin lesions was the second adverse prognostic factor found in multivariate analysis. To our knowledge, the independent prognostic value of variables related to tumor extension has not been demonstrated previously in non–MF/SS PCL. Although tumor extension is an important prognostic parameter in nodal lymphomas3 and seemed useful in PCL, there has been no consensus for its evaluation in non–MF/SS PCL. Distribution, diameter, and number of skin lesions, or a clinical index resulting from a combination of these parameters are candidate variables for assessment of skin tumor burden. Although they were significantly associated with survival in univariate analysis, maximum diameter and number of skin lesions had no independent prognostic value when the EORTC prognostic group was taken into account. In addition, patients with skin lesions localized on one anatomic site showed no difference in survival according to the cutaneous surface involved. Finally, only the involvement of more than one anatomic site was a significant, independent indicator of a poor prognosis. This finding confirms and extends results of previous univariate analyses in small series of patients.24 26 Therefore, a generalized distribution at diagnosis should be recorded as a pertinent prognostic reflect of tumor extension when comparing survival data or evaluating the efficacy of treatments in further studies.

In the present study, age was not a significant prognostic factor. This result seems in contrast with studies that found age to be significantly related to survival in many cancers, including lymphomas.4,5 However, it is noteworthy that age was identified as a prognostic factor in studies that included a large number of older patients4 and that most of these studies used a Cox proportional-hazards model, which is unsatisfactory to clarify the real impact of age in mortality, strictly because of the disease.27 Using a Cox model in our series (data not shown), we found an older age to be significantly related to death (P < .0001). This and the result of the relative survival analysis indicate that elderly patients had an increased mortality from unrelated causes, but no increased risk of death from direct and indirect consequences of lymphoma.

The presence of B symptoms and a high LDH level have been associated with a poor prognosis in large series of patients with nodal lymphomas.1 3-5 Although these parameters were strongly related to survival in univariate analysis in our study, they showed no independent prognostic value in multivariate analysis, because many patients with B symptoms or a high LDH level had an aggressive or intermediate lymphoma according to the EORTC classification or a generalized distribution of skin lesion (Table6). However, these parameters remain useful prognostic indicators that should be recorded at initial evaluation of every patient with PCL.

Optimal treatments of non–MF/SS PCL are still to be determined on the basis of appropriate clinical trials. However, preliminary guidelines may be proposed with regard to previous reports and the present study. Localized CD30-positive large T-cell lymphomas and localized indolent B-cell lymphomas have a very good prognosis and are best treated with radiation therapy alone. CD30-negative large T-cell lymphomas and lymphomas involving more than one anatomic site should be preferentially treated with chemotherapy. However, optimal chemotherapeutic regimens have yet to be defined. Large B-cell lymphomas of the leg have an intermediate prognosis that makes a multiagent chemotherapy more suitable; however, radiotherapy may be considered, especially in elderly patients with localized tumors. Interferon or chemotherapy has been proposed for pleomorphic small T-cell lymphomas,17 but a more accurate evaluation of clinical outcome and treatment is required for this subtype. Treatment of relapses represents a special challenge and should be carefully considered. Although overall 5-year relative survival in our study was 73%, death from lymphoma beyond 5 years was not rare, and relative survival curves do not reach a plateau within a period of 10 years. New treatment modalities may be required to improve long-term survival in PCL.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Khaldoun Kuteifan for technical and linguistic assistance, and the following clinicians, pathologists, and epidemiologists who actively participated in the study: B. Audhuy, S. Briançon, M.P. Cambie, A. Carlotti, A. Colson, P. Courville, P. Dechelotte, A. Durlach, S. Fraitag, Y. Fonck, J.C. Guillaume, F. Husseini, F. Maı̂tre, A. de Muret, T. Petrella, P. Schaffer, B. Schubert, P. Souteyrand, E. Thomine, and M.C. Tortel.

Supported by a grant from the Société Française de Dermatologie.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to F. Grange, Service de Dermatologie, Hôpital Pasteur, 39 avenue de la Liberté 68024 Colmar Cedex, France.