Abstract

To study constitutive Janus kinase signaling, chimeric proteins were generated between the pointed domain of the etstranscription factor TEL and the cytosolic tyrosine kinase Jak2. The effects of these proteins on interleukin-3 (IL-3)–dependent proliferation of the hematopoietic cell line, Ba/F3, were studied. Fusion of TEL to the functional kinase (JH1) domain of Jak2 resulted in conversion of Ba/F3 cells to factor-independence. Importantly, fusion of TEL to the Jak2 pseudokinase (JH2) domain or a kinase-inactive Jak2 JH1 domain had no effect on IL-3–dependent proliferation of Ba/F3 cells. Active TEL-Jak2 constructs (consisting of either Jak2 JH1 or Jak2 JH2+JH1 domain fusions) were constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylated but did not affect phosphorylation of endogeneous Jak1, Jak2, or Jak3. TEL-Jak2 activation resulted in the constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat1, Stat3, and Stat5 as determined by detection of phosphorylation using activation-specific antibodies and by binding of each protein to a preferential GAS sequence in electrophoretic mobility shift assays. Elucidation of signaling events downstream of TEL-Jak2 activation may provide insight into the mechanism of leukemogenesis mediated by this oncogenic fusion protein.

THE Jak-Stat SIGNALING pathway plays a critical role in hematopoiesis. Many constituents of this pathway are essential for normal hematopoietic development, including Jak1,1 Jak2,2,3 Jak3,4-7Stat3,8 Stat4,9,10 Stat5,11 and Stat6.10 12 Because arrested differentiation may contribute to leukemias, the role of this signaling pathway in leukemogenesis is of considerable interest.

Constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of Jak2 and Stat5 have been identified in cell lines derived from acute myelogenous leukemia (AML),13,14 acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL),14,15 chronic myelogeneous leukemia (CML),14 and Burkitt’s lymphoma14 patients. However, because many of these cell lines were isolated from relapsed patients, it is difficult to assess if the activation of the individual Jak and Stat molecules is a primary or secondary event. The direct involvement of Janus kinases in leukemogenesis was illustrated by the discovery of an activating mutation within the JH2 domain of the Drosophila Janus kinase homolog, hopscotch.16 A glutamate to lysine substitution at amino acid 695 causes an overproliferation of Drosophila plasmatocytes, resulting in a lethal phenotype.16 Introduction of a corresponding mutation within Jak2 produced an enzyme with increased catalytic activity, but when overexpressed in Ba/F3 cells offered no proliferative advantage.16

Activated tyrosine kinases have been shown to participate in leukemogenesis. In CML, the Bcr-abl fusion protein generated by a t(9;22) translocation mediates its biological effects through deregulated tyrosine kinase activity.17 The etstranscription factor TEL has been shown to undergo translocation to two different tyrosine kinases, abl18,19 and PDGF-Rβ,20 which results in constitutive activation of each kinase. We were interested in generating a constitutively active Jak to directly address its functional effect in hematopoietic cells. We reasoned that fusion of the helix-loop-helix domain of TEL to Jak2 may generate an active Jak molecule.

In this study, we have generated several TEL-Jak2 fusion proteins and have examined their functional properties by expression in the hematopoietic cell line, Ba/F3. Fusion of TEL to constructs expressing either the kinase (JH1) domain or the kinase and pseudokinase (JH2+JH1) domains of Jak2 results in constitutive activation. In addition, active TEL-Jak2 tyrosine phosphorylates the downstream transcription factors Stat1, Stat3, and Stat5. During the course of this research, 3 patients have been described that express TEL-JAK2 [t(9;12)(p24;p13)] translocations.21 22 This study characterizes the Jak-Stat activation profile mediated by TEL-Jak2 translocation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of TEL-Jak2 constructs.

The regions encompassing nt 1-462 of TEL, nt 1627-2535 ofJak2 (Jak2 JH2), nt 1627-3391 of Jak2 (Jak2 JH2+JH1), and nt 2536-3391 of Jak2 (Jak2 JH1 and KI-Jak2 JH1) were generated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using Vent Polymerase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA). A Kpn I site was incorporated into the forward TEL primer, a BamHI site was incorporated into the reverse TEL primer and each forward Jak2 primer, and an EcoRI site was added to each reverse Jak2primer. The templates for PCR corresponded to TEL,TEL-ΔPNT (TEL constructs were supplied by Dr D.G. Gilliland, Boston, MA), murine Jak2, or a kinase-inactive form of murine Jak2 (KI-Jak2) kindly provided by Dr D. Wojchowski (University Park, PA).23PCR products were subcloned into pCR-Script (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). TEL-Jak2 chimeras were generated by digestion with KpnI-BamHI (TEL) or BamHI-EcoRI (Jak2) and subcloned into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) digested withKpn I-EcoRI.

TEL-Jak2 constructs were tagged by the addition of an HA3-His6 epitope that was added by PCR overlap extension. One fragment corresponding to the HA3-His6 epitope and a second fragment corresponding to nt 1-462 of TEL were generated. Overlap extension was performed, and the resulting product was subcloned into pcDNA3-TEL-Jak2 digested with HindIII andEco47III. The sequence of all constructs was confirmed by sequencing both strands.

Antibodies.

A pan-specific Jak antibody was raised against the Jak2 JH1 domain, as previously described.24 Peptide-specific antibodies to Jak1, Jak2, and Jak3 were obtained from Upstate Biochemical Inc (Lake Placid, NY). Activation-specific Stat1,25Stat3,26 and Stat527 antibodies were raised to a phosphopeptide corresponding to the conserved site of tyrosine phosphorylation of each protein. A Stat1 polyclonal antibody was generously provided by Dr David Levy (New York , NY), Stat1 and Stat3 monoclonal antibodies were obtained from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY), a polyclonal Stat3 antibody was purchased from Zymed Laboratories (San Francisco, CA), and a peptide-specific Stat5 antibody was generously provided by Dr James Ihle (Memphis, TN).

COS cell expression.

COS-7 cells were transfected using the diethyl aminoethyl (DEAE)-dextran, chloroquine method.16 Cells were incubated for 3.5 hours in DEAE-dextran-chloroquine with 5 μg of each TEL-Jak2 construct. Cells were then incubated in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-10% dimethyl sulfoxide for 2 minutes, washed once in PBS, and incubated in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium for 72 hours before harvest. The plates were washed once in a solution containing 10 mmol/L HEPES, Hank’s Balanced Salts, 10 mmol/L Na2P2O7, 10 mmol/L NaF, 1 mmol/L Na3VO4, and 5 mmol/L EDTA. Lysates were then prepared in a buffer containing 50 mmol/L TrisHCl (pH 8.0), 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 10 mmol/L Na2P2O7, 10 mmol/L NaF, 10 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mmol/L Na3VO4, 1 μmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1 μg/mL aprotinin, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, and 2 μg/mL pepstatin A (buffer A). Fifty micrograms of lysate was resolved via sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to nitrocellulose. Tyrosine phosphorylation was detected by incubating the membrane with the monoclonal antiphosphotyrosine antibody, 4G10 (generously provided by Dr Brian Druker, Portland, OR), followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-sheep antimouse IgG. Immunoreactive proteins were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL).

Expression of TEL-Jak2 in Ba/F3 cells.

Various TEL-Jak2 constructs were electroporated into the interleukin-3 (IL-3)–dependent cell line, Ba/F3. Populations of G418-resistant cells were isolated and individual subclones were isolated via limiting dilution.

To analyze the growth properties of each TEL-Jak2 construct, various Ba/F3 TEL-Jak2 subclones were washed three times in PBS and resuspended in RPMI complete medium. Cells were incubated at 5 × 104 cells/mL in the absence or presence of 100 pg/mL IL-3. The number of viable cells was enumerated during each day by trypan blue exclusion.

The expression of each TEL-Jak2 construct was confirmed by performing metabolic labeling and immunoprecipitation using a pan-specific Jak antibody. Cells were incubated in the presence of35S-cys/35S-met for 2 hours. After lysis and preimmune clearance overnight, 5 μL of pan Jak or 2 μL of a peptide-specific Jak2 antibody was added for 1 hour, followed by 30 μL of protein A-Sepharose. After washing, bound proteins were resolved via SDS-PAGE. The gel was fixed in glacial acetic acid, incubated in 50% (wt/vol) 2,5-diphenyloxazole prepared in glacial acetic acid, and dried, and labeled proteins were analyzed by PhosphorImager detection (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

Analysis of tyrosine phosphorylation.

Ba/F3 TEL-Jak2 subclones were depleted of cytokine for 4 hours and then stimulated in the presence or absence of 100 ng/mL IL-3 for 5 minutes. Lysates were prepared in buffer A.

For the analysis of TEL-Jak2 and endogeneous Jak kinase phosphorylation, 2 mg of lysate was incubated with the appropriate antibody and immune complexes were captured on protein A-Sepharose. Bound proteins were resolved via SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. After blocking, the membrane was incubated with a monoclonal antiphosphotyrosine antibody, 4G10. After washing, the membrane was incubated with HRP-sheep antimouse IgG. The membrane was washed extensively for 30 minutes and tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins were detected by ECL.

For analysis of Stat tyrosine phosphorylation, 100 μg of each lysate was resolved via SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. The membrane was blocked and then incubated with the appropriate activation-specific Stat antibody, followed by HRP-protein A and ECL detection. Each membrane was then stripped and reprobed with the appropriate Stat antibody.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs).

Nuclear extracts were prepared from Ba/F3 TEL-Jak2 subclones stimulated in the presence or absence of 100 ng/mL IL-3. Cell pellets were resuspended in 1.0 mL of buffer B (10 mmol/L HEPES [pH 7.9], 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 10 mmol/L KCl, 0.5 mmol/L dithiothreitol [DTT], 1 mmol/L PMSF, 5 μg of aprotinin per milliliter, 5 μg of leupeptin per milliliter, and 5 μg of pepstatin A per milliliter) and allowed to swell on ice for 10 minutes. Cells were then vortexed for 10 seconds and centrifuged at 10,000g for 10 seconds, and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was washed once in buffer B and then nuclear proteins were resuspended in an appropriate volume of buffer C (20 mmol/L HEPES [pH 7.9], 25% glycerol, 420 mmol/L NaCl, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.2 mmol/L EDTA, 0.5 mmol/L DTT, 1 mmol/L PMSF, 5 μg of aprotinin per milliliter, 5 μg of leupeptin per milliliter, and 5 μg of pepstatin A per milliliter).

Gel shift experiments were performed with a double-stranded32P-labeled oligonucleotide derived from the β-casein promoter (AGATTTCTAGGAATTCAAATC)28 or from the IRF-1 promoter (CTGATTTCCCCGAAATGAC).29 Two micrograms of nuclear extract was mixed with 0.25 ng of the 32P-labeled oligonucleotide in 20 μL of binding buffer [13 mmol/L HEPES (pH 7.9), 65 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L DTT, 0.15 mmol/L EDTA, 8% glycerol, 50 μg of poly (dI-dC) per milliliter] for 20 minutes at 4°C. For competition experiments, a 50-fold excess of either the unlabeled β-casein or IRF-1 oligonucleotide (specific) or an oligonucleotide derived from the DUB-1 promoter (nonspecific)30 was added to the binding reaction. For supershifting experiments, a peptide-specific Stat1 (Dr David Levy), Stat3 (Zymed), or a Stat5 antibody (Dr James Ihle) was added at the completion of the binding reaction and incubated for an additional 20 minutes at 4°C.

RESULTS

Generation of TEL-Jak2 constructs.

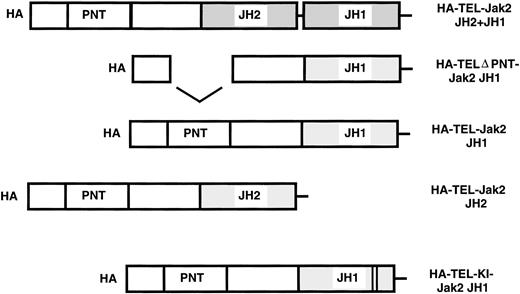

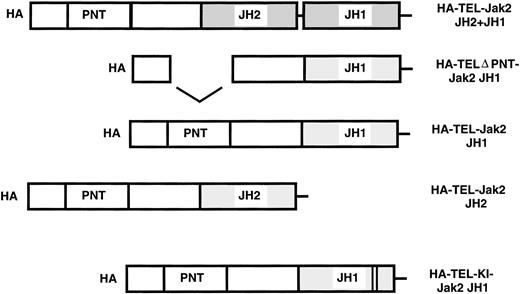

To assess the activity of TEL-Jak2 fusion proteins, five chimeric constructs were prepared. Fusions were generated between the exon 4 breakpoint of TEL at amino acid 154 to various regions of Jak2. Chimeric TEL-Jak2 proteins were generated to the functional kinase (JH1) domain of Jak2 (TEL-Jak2 JH1), the pseudokinase (JH2) and kinase (JH1) domain (TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1), and the pseudokinase domain (TEL-Jak2 JH2). To test for the involvement of the helix-loop-helix or pointed31 domain (conserved in a subset of ets proteins including TEL) in Jak2 activation, a construct was created that deletes amino acids 65-116 of TEL (TELΔPNT-TEL-Jak2 JH1).32 TEL was also fused to a kinase-inactive form of Jak2 (TEL-Jak2-KI-Jak2). Subsequently, the constructs were epitope tagged at the amino terminus with HA3HIS6 (HA) (see Materials and Methods for further details).

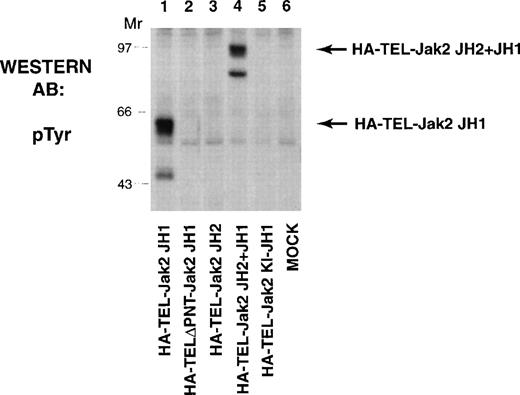

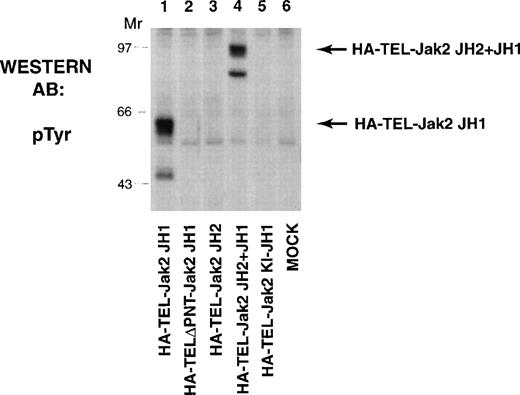

The TEL-Jak2 constructs (Fig 1) were first expressed in COS cells and tyrosine phosphorylation was analyzed to determine kinase activation (Fig 2). HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 (lane 1) and HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1 (lane 4) were both tyrosine-phosphorylated. However, the HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2 fusion protein was not tyrosine-phosphorylated (lane 3), indicating that fusion of TEL to the Jak2 pseudokinase domain did not result in an active kinase. Similarly, a fusion protein consisting of TEL and a kinase-inactive version of Jak2 was not tyrosine-phosphorylated (lane 5). The pointed domain of TEL is also required for TEL-Jak2 activation, because HA-TELΔPNT-Jak2 JH1 was not tyrosine-phosphorylated in this experiment (lane 2).

TEL-Jak2 constructs. The various TEL-Jak2 constructs that were used in this study. TEL-Jak2 JH1 corresponds to TEL (amino acids 1-154) fused to the JH1 domain of Jak2 (amino acids 846-1129). The TEL▵PNT construct fuses TEL deleted in amino acids (65-116) to the Jak2 JH1 domain (amino acids 846-1129). TEL-Jak2 JH2 encompasses a fusion of TEL (1-154) to amino acids 543-845 of Jak2. The TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1 construct fuses TEL (1-154) to amino acids 543-1129 of Jak2. TEL-KI-Jak2 JH1 fuses TEL (1-154) to a kinase-inactive form of Jak2 (amino acids 846-1129). All constructs were epitope tagged at the amino terminus with HA3His6 (HA). For additional details, please refer to Materials and Methods.

TEL-Jak2 constructs. The various TEL-Jak2 constructs that were used in this study. TEL-Jak2 JH1 corresponds to TEL (amino acids 1-154) fused to the JH1 domain of Jak2 (amino acids 846-1129). The TEL▵PNT construct fuses TEL deleted in amino acids (65-116) to the Jak2 JH1 domain (amino acids 846-1129). TEL-Jak2 JH2 encompasses a fusion of TEL (1-154) to amino acids 543-845 of Jak2. The TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1 construct fuses TEL (1-154) to amino acids 543-1129 of Jak2. TEL-KI-Jak2 JH1 fuses TEL (1-154) to a kinase-inactive form of Jak2 (amino acids 846-1129). All constructs were epitope tagged at the amino terminus with HA3His6 (HA). For additional details, please refer to Materials and Methods.

TEL-Jak2 JH1 and TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1 are constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylated in COS cells. COS cells were transfected with the constructs as indicated. Fifty micrograms of lysate was resolved via SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. The membrane was incubated with a monoclonal antiphosphotyrosine antibody followed by HRP-sheep antimouse IgG. The position of each tyrosine-phosphorylated protein and molecular weight standards are indicated.

TEL-Jak2 JH1 and TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1 are constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylated in COS cells. COS cells were transfected with the constructs as indicated. Fifty micrograms of lysate was resolved via SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. The membrane was incubated with a monoclonal antiphosphotyrosine antibody followed by HRP-sheep antimouse IgG. The position of each tyrosine-phosphorylated protein and molecular weight standards are indicated.

Expression of TEL-Jak2 JH1 results in conversion of Ba/F3 cells to factor independence.

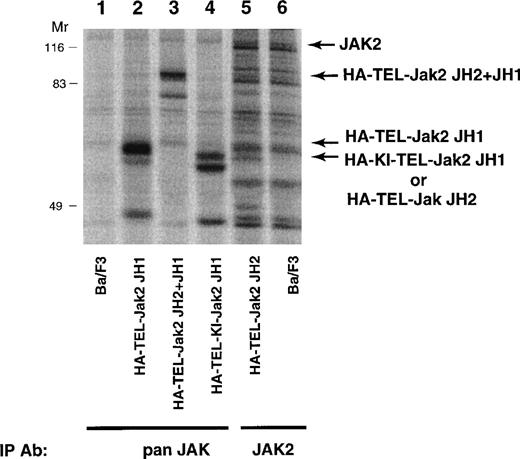

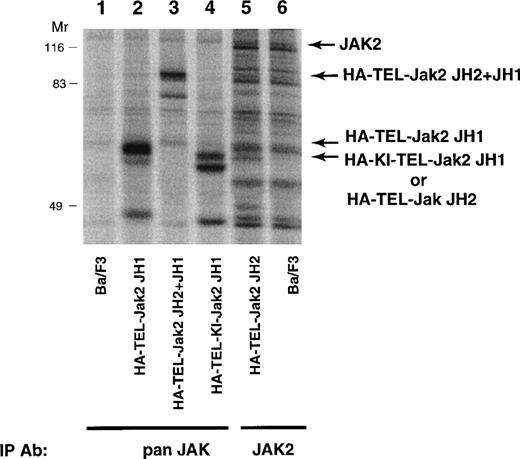

To determine the biological activity of these fusion proteins, TEL-Jak2 constructs were expressed in the IL-3–dependent murine cell line, Ba/F3. Individual G418-resistant subclones were isolated by limiting dilution and the level of expression was examined by metabolic labeling (Fig 3). Labeled lysates were either immunoprecipitated with an anti-Jak2 JH2 domain antibody (HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2) or an anti-Jak2 JH1 domain antibody (remaining constructs) and, after SDS-PAGE, proteins were visualized by fluorography. The expected molecular weights for each of the fusion proteins are HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 (56 kD), HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2 (55 kD), HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1 (95 kD), and HA-TEL-KI-Jak2 JH1 (56 kD). Because of tyrosine phosphorylation, HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 and HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1 migrated at a slightly higher molecular weight. Subclones that had similar expression levels were selected for the remaining studies.

Expression of TEL-Jak2 fusion proteins in Ba/F3 cells. Ba/F3 (lanes 1 and 6), Ba/F3-HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 subclone 36 (lane 2), Ba/F3-HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1 subclone 23 (lane 3), Ba/F3-HA-TEL-KI-Jak2 JH1 subclone 11 (lane 4), and Ba/F3-HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2 subclone 4 (lane 5) were metabolically labeled with35S-cys/35S-met. Immunoprecipitations were conducted with Jak2 antibodies that recognized the Jak2 JH1 domain (pan Jak, lanes 1 through 4) or Jak2 JH2 domain (Jak2, lanes 5 and 6). Immunoreactive species were analyzed via PhosphorImager detection.

Expression of TEL-Jak2 fusion proteins in Ba/F3 cells. Ba/F3 (lanes 1 and 6), Ba/F3-HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 subclone 36 (lane 2), Ba/F3-HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1 subclone 23 (lane 3), Ba/F3-HA-TEL-KI-Jak2 JH1 subclone 11 (lane 4), and Ba/F3-HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2 subclone 4 (lane 5) were metabolically labeled with35S-cys/35S-met. Immunoprecipitations were conducted with Jak2 antibodies that recognized the Jak2 JH1 domain (pan Jak, lanes 1 through 4) or Jak2 JH2 domain (Jak2, lanes 5 and 6). Immunoreactive species were analyzed via PhosphorImager detection.

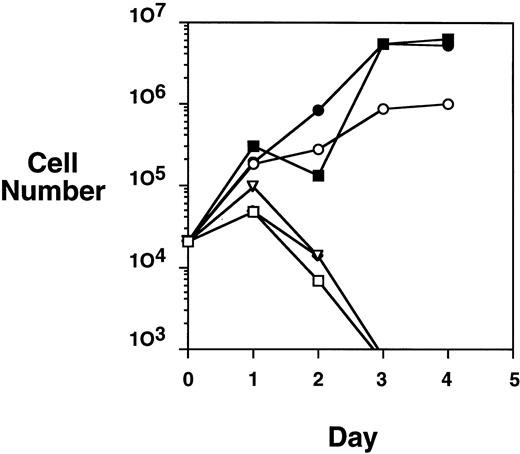

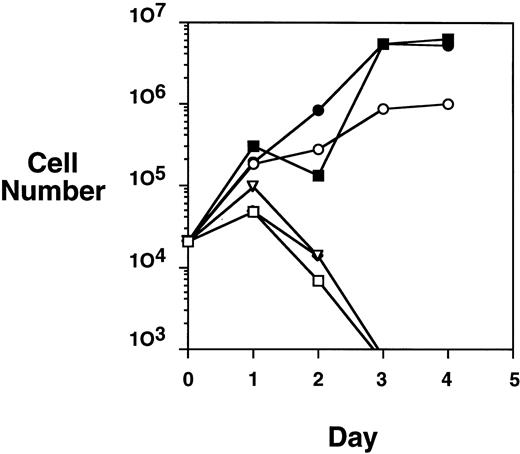

Because the HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 construct was constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylated in COS cells, we were interested in determining if this construct offered a proliferative advantage when expressed in the Ba/F3 cell line. A proliferation assay was performed by monitoring the numbers of cells accumulated over a 4-day period when Ba/F3-TEL-Jak2 subclones were incubated in the presence or absence of IL-3 (Fig 4). HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 subclone cells grew in the absence of IL-3 during the period of this experiment. As expected, the expression of HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2 had no effect on IL-3–dependent growth, and this cell line was incapable of proliferation in the absence of exogenous cytokine. Importantly, Ba/F3 cells expressing HA-TEL-KI-Jak2 JH1 did not display factor-independent growth in RPMI complete medium and there was no alteration in IL-3–dependent growth when compared with untransfected Ba/F3 cells (data not shown). This indicates that a kinase-inactive TEL-Jak2 fusion protein does not interfere with the IL-3–dependent activation of endogeneous Jak1 or Jak2. Ba/F3 cells expressing untagged versions of the identical TEL-Jak2 constructs were tested in the same assay and showed identical growth properties. As a result, HA-tagged constructs were used in the remainder of the study.

TEL-Jak2 JH1 transforms Ba/F3 cells to factor-independence. Ba/F3 cells (5 × 104 cells) expressing various TEL-Jak2 constructs were incubated in the presence or absence of 100 pg/mL IL-3 for 4 days. Viable cells were enumerated by Trypan blue exclusion. (□) Ba/F3, no IL-3; (▪) Ba/F3, plus IL-3; (○) Ba/F3-HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 subclone 36, no IL-3; (•) Ba/F3-HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 subclone 36, plus IL-3; (▵) Ba/F3-HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2 subclone 4, no IL-3; (◊) Ba/F3-HA-TEL-KI-Jak2 subclone 11, no IL-3. The IL-3–dependent growth of Ba/F3-TEL-Jak2 JH2 and Ba/F3-TEL-KI-Jak2 JH1 was exactly similar to that of Ba/F3 cells and has been omitted for clarity.

TEL-Jak2 JH1 transforms Ba/F3 cells to factor-independence. Ba/F3 cells (5 × 104 cells) expressing various TEL-Jak2 constructs were incubated in the presence or absence of 100 pg/mL IL-3 for 4 days. Viable cells were enumerated by Trypan blue exclusion. (□) Ba/F3, no IL-3; (▪) Ba/F3, plus IL-3; (○) Ba/F3-HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 subclone 36, no IL-3; (•) Ba/F3-HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 subclone 36, plus IL-3; (▵) Ba/F3-HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2 subclone 4, no IL-3; (◊) Ba/F3-HA-TEL-KI-Jak2 subclone 11, no IL-3. The IL-3–dependent growth of Ba/F3-TEL-Jak2 JH2 and Ba/F3-TEL-KI-Jak2 JH1 was exactly similar to that of Ba/F3 cells and has been omitted for clarity.

Activated TEL-Jak2 constructs are constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylated in Ba/F3 cells.

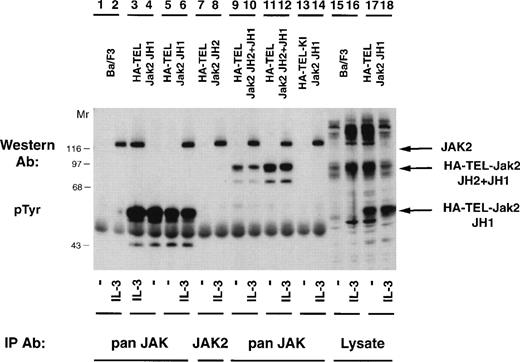

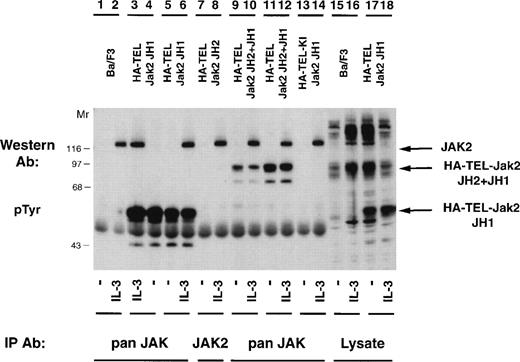

Once it was determined that activated TEL-Jak2 constructs resulted in IL-3–independent proliferation in Ba/F3 cells, tyrosine phosphorylation of the chimeric proteins was examined (Fig 5). Individual Ba/F3 subclones expressing each TEL-Jak2 construct were incubated in the presence or absence of IL-3 and the tyrosine phosphorylation of each construct was analyzed. Two subclones of Ba/F3-HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 cells displayed constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of a 56-kD protein (lanes 4 and 5). Similarly, Ba/F3-HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1 subclones expressed a 95-kD protein that was constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylated (lanes 9 and 11). As observed in the COS cell experiments, the HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2 (lanes 7 and 8) and HA-TEL-KI-Jak2 JH1 (lanes 13 and 14) chimeras were not tyrosine-phosphorylated when expressed in Ba/F3 cells. Whereas IL-3 activated the tyrosine phosphorylation of Jak2 in all cell lines, IL-3 did not stimulate the tyrosine phosphorylation of HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2 (lane 8) or HA-TEL-KI-Jak2 JH1 (lane 14), indicating that the IL-3 receptor does not couple to TEL-Jak2 in Ba/F3 cells.

TEL-Jak2 fusion proteins are constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylated in Ba/F3 cells. Ba/F3 (lanes 1, 2, 15, and 16), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 subclone 18 (lanes 3, 4, 17, and 18), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 subclone 36 (lanes 5 and 6), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2 subclone 4 (lanes 7 and 8), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1 subclone 23 (lanes 9 and 10), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1 subclone 31 (lanes 11 and 12), and Ba/F3 HA-TEL-KI-Jak2 subclone 11 (lanes 13 and 14) cells were depleted of cytokine and stimulated in the presence or absence of IL-3. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with an antibody that recognizes the Jak2 JH1 domain (pan Jak, lanes 1 through 6 and 9 through 14) or the Jak2 JH2 domain (Jak2, lanes 7 and 8) and tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins were detected by immunoblotting with a monoclonal antiphosphotyrosine antibody. Lysate controls are shown in lanes 15 through 18. The mobility of tyrosine-phosphorylated Jak2, HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1, and HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1 are indicated.

TEL-Jak2 fusion proteins are constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylated in Ba/F3 cells. Ba/F3 (lanes 1, 2, 15, and 16), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 subclone 18 (lanes 3, 4, 17, and 18), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 subclone 36 (lanes 5 and 6), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2 subclone 4 (lanes 7 and 8), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1 subclone 23 (lanes 9 and 10), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1 subclone 31 (lanes 11 and 12), and Ba/F3 HA-TEL-KI-Jak2 subclone 11 (lanes 13 and 14) cells were depleted of cytokine and stimulated in the presence or absence of IL-3. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with an antibody that recognizes the Jak2 JH1 domain (pan Jak, lanes 1 through 6 and 9 through 14) or the Jak2 JH2 domain (Jak2, lanes 7 and 8) and tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins were detected by immunoblotting with a monoclonal antiphosphotyrosine antibody. Lysate controls are shown in lanes 15 through 18. The mobility of tyrosine-phosphorylated Jak2, HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1, and HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1 are indicated.

TEL-Jak2 tyrosine phosphorylation does not activate tyrosine kinase activity of endogenous Janus kinases.

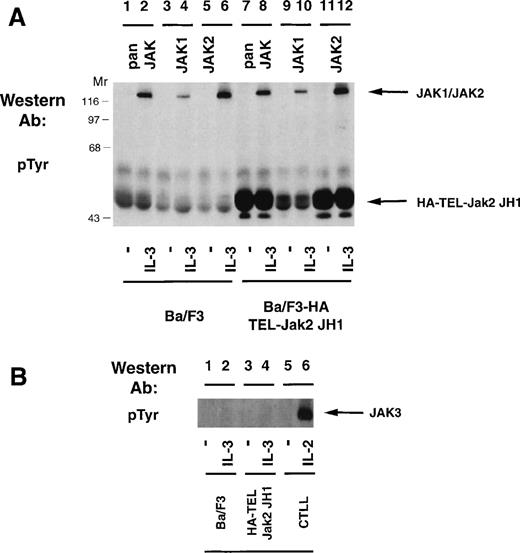

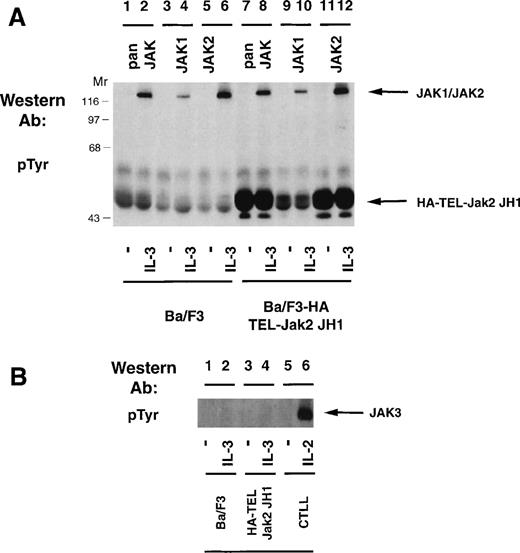

Because expression of HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 in Ba/F3 cells resulted in factor-independent proliferation and constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of the resulting fusion protein, we were interested in determining whether the HA-TEL-Jak2 chimeras could activate the tyrosine phosphorylation of the endogenous Jak kinases. Ba/F3 or Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 cells were incubated in the absence or presence of IL-3 and the tyrosine phosphorylation of Jak1 and Jak2 was assessed (Fig 6A). IL-3 stimulation resulted in the tyrosine phosphorylation of Jak1 (lane 4) and Jak2 (lane 6) in Ba/F3 cells. Despite constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 in the absence of IL-3 stimulation (lanes 7 and 11), no tyrosine phosphorylation of Jak1 or Jak2 was observed using a pan-Jak antibody (lane 7), a Jak1 antibody (lane 9), or a Jak2 antibody (lane 11). Ba/F3, Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1, and CTLL cells were examined for Jak3 activation (Fig 6B). IL-2 activates the tyrosine phosphorylation of Jak3 in CTLL cells (lane 6), as previously reported.24,33However, no constitutive activation of Jak3 was observed in HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 cells in the absence of IL-3 stimulation (lane 3). Thus, the HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 protein does not activate endogenous Jak1, Jak2, or Jak3. Furthermore, no Jak kinases are observed to be tyrosine-phosphorylated in the pan-Jak immunoprecipitation (Fig 6A, lane 7). This antibody specifically recognizes the JH1 domain of all mammalian Jak kinases, including Tyk2.24 Therefore, we believe that fusion of TEL to Jak2 results in constitutive activation, independent of endogenous JAK tyrosine kinase activity.

TEL-Jak2 expression does not activate tyrosine phosphorylation of Jak1, Jak2, or Jak3. (A) Ba/F3 (lanes 1 through 6) or Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 subclone 36 (lanes 7 through 12) cells were depleted of cytokine and stimulated in the presence or absence of IL-3. Immunoprecipitations were performed with a pan-specific Jak antibody, a Jak1 antibody, or a Jak2 antibody. Tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins were detected by immunoblotting with a monoclonal antiphosphotyrosine antibody. The migration of endogenous Jak proteins and TEL-Jak2 JH1 and molecular weight standards are indicated. (B) Ba/F3 (lanes 1 and 2) or Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 subclone 36 (lanes 3 and 4) or CTLL (lanes 5 and 6) cells were depleted of cytokine and stimulated in the presence or absence of IL-3 (lanes 1 through 4) or IL-2 (lanes 5 and 6). Immunoprecipitations were performed with a Jak3 antibody. Tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins were detected as described above.

TEL-Jak2 expression does not activate tyrosine phosphorylation of Jak1, Jak2, or Jak3. (A) Ba/F3 (lanes 1 through 6) or Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 subclone 36 (lanes 7 through 12) cells were depleted of cytokine and stimulated in the presence or absence of IL-3. Immunoprecipitations were performed with a pan-specific Jak antibody, a Jak1 antibody, or a Jak2 antibody. Tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins were detected by immunoblotting with a monoclonal antiphosphotyrosine antibody. The migration of endogenous Jak proteins and TEL-Jak2 JH1 and molecular weight standards are indicated. (B) Ba/F3 (lanes 1 and 2) or Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 subclone 36 (lanes 3 and 4) or CTLL (lanes 5 and 6) cells were depleted of cytokine and stimulated in the presence or absence of IL-3 (lanes 1 through 4) or IL-2 (lanes 5 and 6). Immunoprecipitations were performed with a Jak3 antibody. Tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins were detected as described above.

Activation of TEL-Jak2 results in constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat5.

Constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of Janus kinases and, subsequently, Stat transcription factors has been documented in cell lines isolated from CML,14 AML,14,34ALL,14,15 and Burkitt’s lymphoma patients.14Many cytokines, including IL-2,35,36 IL-3,37,38IL-5,38 granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF),38,39 erythropoietin (EPO),35,39-42Prolactin,28 and growth hormone,39 activate the tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat5. Thus, we were interested in determining whether activated TEL-Jak2 fusion proteins could phosphorylate Stat proteins. Because of the important role of Stat5 in cytokine signaling, we first examined Stat5.

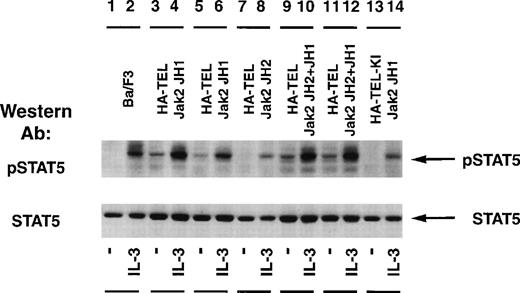

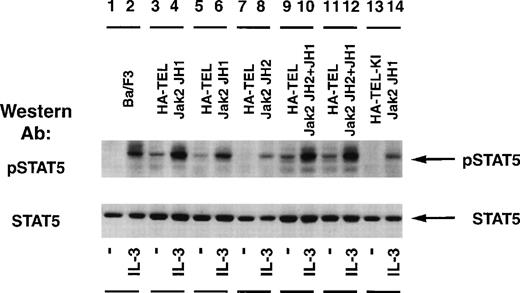

The status of Stat5 tyrosine phosphorylation was tested using an activation-specific Stat5 antibody that selectively recognizes Stat5 tyrosine-phosphorylated at position 694 (Fig 7). Stimulation of Ba/F3 cells with IL-3 resulted in a rapid tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat5 (lane 2) when compared with unstimulated cells (lane 1). Isolated subclones of Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 (lanes 3 and 5) and Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1 (lanes 9 and 11) demonstrated constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat5. As observed above, HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2 or HA-TEL-KI-Jak2 JH1 were not tyrosine-phosphorylated and failed to activate the tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat5 under resting conditions. Stripping and reprobing the membrane with an antibody that recognized Stat5A and B showed that equal amounts of protein were expressed in each cell line (Fig 7, lower panel).

Stat5 is constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylated in Ba/F3 cells expressing activated TEL-Jak2. Ba/F3 (lanes 1 and 2), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 subclone 18 (lanes 3 and 4), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 subclone 36 (lanes 5 and 6), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2 subclone 4 (lanes 7 and 8), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1 subclone 23 (lanes 9 and 10), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1 subclone 31 (lanes 11 and 12), and Ba/F3 HA-TEL-KI-Jak2 subclone 11 (lanes 13 and 14) cells were depleted of cytokine and stimulated in the presence or absence of IL-3. One hundred micrograms of lysate was resolved via SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Tyrosine-phosphorylated Stat5 was detected using an activation-specific Stat5 antibody. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with a peptide-specific Stat5 antibody.

Stat5 is constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylated in Ba/F3 cells expressing activated TEL-Jak2. Ba/F3 (lanes 1 and 2), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 subclone 18 (lanes 3 and 4), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 subclone 36 (lanes 5 and 6), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2 subclone 4 (lanes 7 and 8), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1 subclone 23 (lanes 9 and 10), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1 subclone 31 (lanes 11 and 12), and Ba/F3 HA-TEL-KI-Jak2 subclone 11 (lanes 13 and 14) cells were depleted of cytokine and stimulated in the presence or absence of IL-3. One hundred micrograms of lysate was resolved via SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Tyrosine-phosphorylated Stat5 was detected using an activation-specific Stat5 antibody. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with a peptide-specific Stat5 antibody.

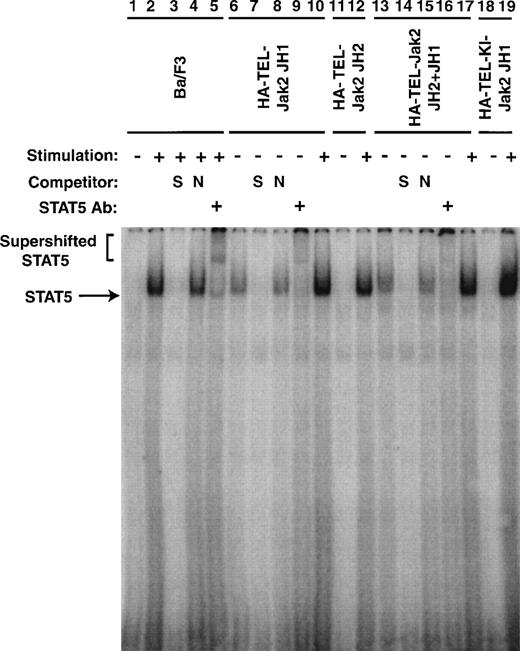

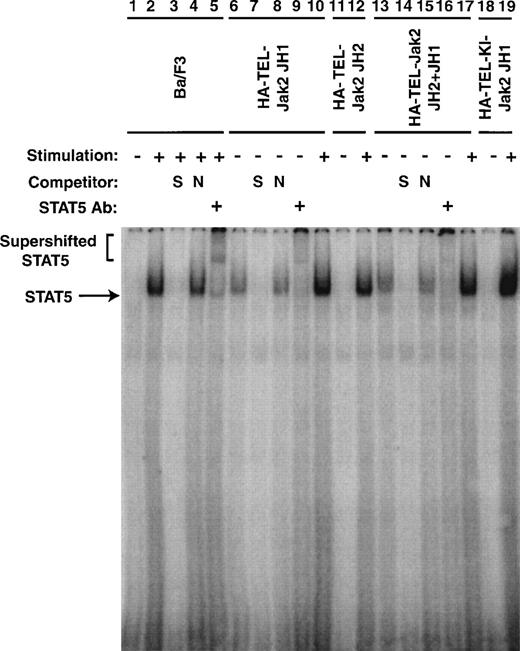

To confirm that the tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat5 was associated with an increase in DNA binding, EMSAs were performed (Fig 8). Nuclear extracts were prepared from the cell lines described in Figs 5 and 7. The ability of Stat5 to bind to a consensus 32P-labeled oligonucleotide from β-casein gene was examined. In the absence of IL-3 stimulation of parental cells, no protein-DNA complex was observed (lane 1). When the cells were stimulated with IL-3 for 5 minutes, a complex was observed (lane 2). This complex could be competed with an excess of unlabeled β-casein oligonucleotide (lane 3), but was not affected by the addition of an excess of a nonspecific oligonucleotide (lane 4). This DNA-protein complex contained Stat5 as a peptide-specific Stat5 antibody could supershift this complex (lane 5). Nuclear extracts prepared from Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 and Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1 cells possessed constitutive Stat5 DNA binding activity (lanes 6 and 13). The specificity of this Stat5 complex was demonstrated in an identical manner by the inhibition of protein-DNA binding by specific (lanes 7 and 14) but not by nonspecific (lanes 8 and 15) oligonucleotide competitors and by the supershifting of the complex by a peptide-specific Stat5 antibody (lanes 9 and 16). Stat5 binding was only IL-3–inducible in Ba/F3 cells expressing HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2 (lane 12) or HA-TEL-KI-Jak2 JH1 (lane 19). Therefore, Stat5 is activated basally only in the presence of an activated TEL-Jak2 chimera.

Stat5 DNA binding is constitutively activated in TEL-Jak2 transformed Ba/F3 cells. Nuclear extracts were prepared from Ba/F3 (lanes 1 through 5), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 subclone 36 (lanes 6 through 10), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2 subclone 4 (lanes 11 and 12), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1 subclone 23 (lanes 13 through 17), and Ba/F3 HA-TEL-KI-Jak2 subclone 11 (lanes 18 and 19) cells stimulated in the presence (+) or absence (−) of IL-3. EMSAs were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Complexes were resolved on a 5% native polyacrylamide gel. The specificity of DNA binding was determined by the addition of unlabeled β-casein oligonucleotide (S) or a nonspecific oligonucleotide from the DUB-1 promoter (N) and by incubation with a peptide-specific Stat5 antibody. Complexes were analyzed via PhosphorImager detection.

Stat5 DNA binding is constitutively activated in TEL-Jak2 transformed Ba/F3 cells. Nuclear extracts were prepared from Ba/F3 (lanes 1 through 5), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 subclone 36 (lanes 6 through 10), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2 subclone 4 (lanes 11 and 12), Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1 subclone 23 (lanes 13 through 17), and Ba/F3 HA-TEL-KI-Jak2 subclone 11 (lanes 18 and 19) cells stimulated in the presence (+) or absence (−) of IL-3. EMSAs were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Complexes were resolved on a 5% native polyacrylamide gel. The specificity of DNA binding was determined by the addition of unlabeled β-casein oligonucleotide (S) or a nonspecific oligonucleotide from the DUB-1 promoter (N) and by incubation with a peptide-specific Stat5 antibody. Complexes were analyzed via PhosphorImager detection.

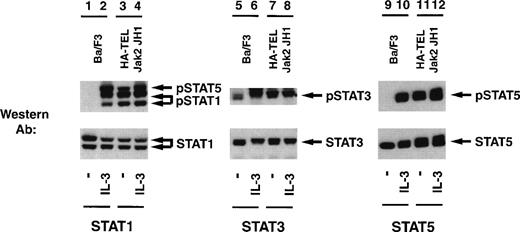

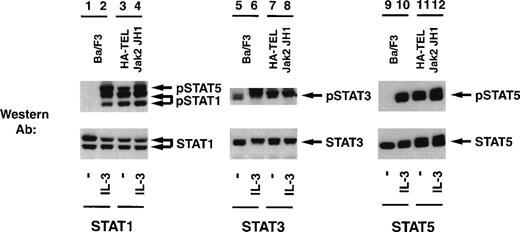

Given the potential importance of other Stat proteins in cell proliferation, we also tested for the ability of HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 to constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylate Stat1, Stat3, Stat5, and Stat6 using a panel of activation-specific antibodies (Fig 9). Lysates were prepared from Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 and untransfected Ba/F3 cells after stimulation with IL-3. Tyrosine-phosphorylated Stat proteins were detected with each respective activation-specific antibody. Constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of both Stat1 and Stat5 was detected using the activation-specific Stat1 antibody (lane 3), which cross-reacts with phosphorylated Stat5.25 Similarly, Stat3 was constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylated in the absence of IL-3 stimulation in Ba/F3 cells expressing HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 (lane 7). However, there are low levels of basal Stat3 tyrosine phosphorylation in unstimulated Ba/F3 cells (lane 5). As demonstrated previously, Stat5 is constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylated in Ba/F3 cells expressing HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 (lane 11). We observed no constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat6 in Ba/F3-HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 cells (data not shown). Stripping and reprobing each membrane with an antibody that recognized either total Stat1, Stat3, or Stat5, respectively, confirmed equal loading in each lane (Fig 9, lower panels). We have performed similar experiments with peptide-specific antibodies to Stat1, Stat3, and Stat5 and have shown that, after detection with 4G10 immunoblotting, HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylates Stat1, Stat3, and Stat5 (data not shown). Thus, multiple Stats become tyrosine-phosphorylated in cells expressing activated TEL-Jak2 fusion proteins.

TEL-Jak2 JH1 expression results in constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat1, Stat3, and Stat5. Ba/F3 (lanes 1, 2, 5, 6, 9, and 10) and Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 subclone 36 cells (lanes 3, 4, 7, 8, 11, and 12) were depleted of cytokine and stimulated in the presence or absence of IL-3. One hundred micrograms of lysate was resolved via SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Tyrosine-phosphorylated Stat proteins were detected using an activation-specific Stat1 antibody (lanes 1 through 4, upper panel), activation-specific Stat3 antibody (lanes 5 through 8, upper panel), or an activation-specific Stat5 antibody (lanes 9 through 12, upper panel). The membrane was stripped and reprobed with peptide-specific antibodies that recognized Stat1 (lanes 1 through 4, lower panel), Stat3 (lanes 5 through 8, lower panel), or Stat5 (lanes 9 through 12, lower panel).

TEL-Jak2 JH1 expression results in constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat1, Stat3, and Stat5. Ba/F3 (lanes 1, 2, 5, 6, 9, and 10) and Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 subclone 36 cells (lanes 3, 4, 7, 8, 11, and 12) were depleted of cytokine and stimulated in the presence or absence of IL-3. One hundred micrograms of lysate was resolved via SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Tyrosine-phosphorylated Stat proteins were detected using an activation-specific Stat1 antibody (lanes 1 through 4, upper panel), activation-specific Stat3 antibody (lanes 5 through 8, upper panel), or an activation-specific Stat5 antibody (lanes 9 through 12, upper panel). The membrane was stripped and reprobed with peptide-specific antibodies that recognized Stat1 (lanes 1 through 4, lower panel), Stat3 (lanes 5 through 8, lower panel), or Stat5 (lanes 9 through 12, lower panel).

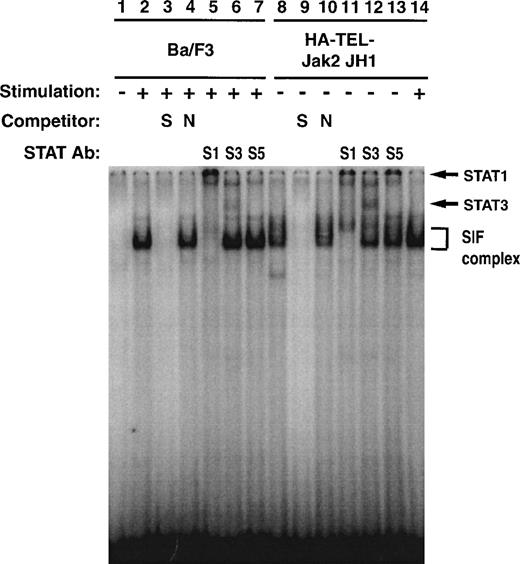

To further investigate the specificity of TEL-Jak2–mediated Stat1 and Stat3 activation, EMSA experiments were performed using32P-labeled IRF-1 as a probe (Fig 10). Ba/F3 cells respond to interferon-α (IFN-α) and assemble an SIF complex (lane 2) that can be supershifted with Stat1 (lane 5), Stat3 (lane 6), but not Stat5 (lane 7) antibodies. Ba/F3-HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 cells also activate an SIF complex (lane 8) in the absence of IFN-α stimulation, which can be supershifted by peptide-specific Stat1 (lane 11) and Stat3 (lane 12) antibodies. The IFN-α–inducible complex is indicated in lane 14. In sum, the experiments presented in Figs 7 through 10 indicate that HA-Tel-Jak2 JH1 activates Stat1, Stat3, and Stat5.

Stat1 and Stat3 DNA binding is constitutively activated in TEL-Jak2 transformed Ba/F3 cells. Nuclear extracts were prepared from Ba/F3 (lanes 1 through 7) and Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 subclone 36 (lanes 8 through 14) cells stimulated in the presence (+) or absence (−) of IFN-. EMSAs were performed as described in Materials and Methods using a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide from the IRF-1 promoter. Complexes were resolved on a 5% native polyacrylamide gel. The specificity of DNA binding was determined by the addition of unlabeled IRF-1 oligonucleotide (S) or a nonspecific oligonucleotide from the DUB-1 promoter (N) and by incubation with peptide-specific Stat1 (S1), Stat3 (S3), or Stat5 (S5) antibodies. Complexes were analyzed via PhosphorImager detection.

Stat1 and Stat3 DNA binding is constitutively activated in TEL-Jak2 transformed Ba/F3 cells. Nuclear extracts were prepared from Ba/F3 (lanes 1 through 7) and Ba/F3 HA-TEL-Jak2 JH1 subclone 36 (lanes 8 through 14) cells stimulated in the presence (+) or absence (−) of IFN-. EMSAs were performed as described in Materials and Methods using a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide from the IRF-1 promoter. Complexes were resolved on a 5% native polyacrylamide gel. The specificity of DNA binding was determined by the addition of unlabeled IRF-1 oligonucleotide (S) or a nonspecific oligonucleotide from the DUB-1 promoter (N) and by incubation with peptide-specific Stat1 (S1), Stat3 (S3), or Stat5 (S5) antibodies. Complexes were analyzed via PhosphorImager detection.

DISCUSSION

It has now been documented that the pointed domain of TEL acts as a dimerization interface that is capable of activating several tyrosine kinases, including PDGF-Rβ,20,32,43 ABL,19ARG,44 TRKC,45,46 STK-1,47 and JAK2.21,22 48 In this study, fusion of TEL to Jak2 generated a constitutively activated tyrosine kinase that converted IL-3–dependent Ba/F3 cells to factor independence. In addition, active TEL-Jak2 products were tyrosine-phosphorylated and resulted in the constitutive activation of Stat1, Stat3, and Stat5.

Fusion of the TEL-pointed domain to either the Jak2 JH1 or Jak2 JH2+JH1 domains was sufficient to cause constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of each chimeric protein. A TEL-Jak2 JH2 fusion was not active, confirming that the Jak2 JH2 domain does not possess catalytic activity. Importantly, a TEL-KI-Jak2 JH1 domain construct was not tyrosine-phosphorylated and did not inhibit IL-3–dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of endogenous Jak2.

Expression of TEL-Jak2 in the hematopoietic cell line Ba/F3 resulted in constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of the fusion protein in the absence of IL-3. We failed to observe TEL-Jak2–dependent phosphorylation of the IL-3 R βc (data not shown) or endogeneous Jak149 or Jak2,49,50 which are known to be activated in an IL-3–dependent manner. We failed to observe activation of Jak3 by TEL-Jak2, and no antibodies are available that immunoprecipitate murine Tyk2. However, no Jak activation was observed in immunoprecipitations using a pan-Jak antibody, a reagent that recognizes all murine Jak proteins.24 Other studies have shown that Stat proteins, including Stat5, can be activated in a receptor-independent fashion, suggesting that the tyrosine kinase or kinase-specific substrate can recruit Stat5.41,51 Published studies have shown that the binding specificity for docking of Stat5 is pYXXL/V41,52,53 and the TEL-Jak2 JH1 sequence contains at least six putative Stat5 docking sites. In addition, we have also observed that TEL-Jak2 JH1 mediates constitutive Stat1 and Stat3 tyrosine phosphorylation. The TEL-Jak2 JH1 sequence contains one Stat1 binding site (pYXXQ)54 and two putative Stat3 binding sites (pYXXP).55 56 Therefore, TEL-Jak2 JH1 could potentially directly recruit and activate Stat1, Stat3, and Stat5. The significance of Stat activation awaits the elucidation of target genes specific to TEL-Jak2–mediated transformation.

Other studies have reported that Stat5 tyrosine phosphorylation and DNA binding activity is also observed downstream of Bcr-abl.57-61 This suggests that Stat5 activation may be implicated in Bcr-Abl–mediated leukemogenesis. Interestingly, a constitutively active Stat5 molecule was recently identified that, when overexpressed in Ba/F3 cells, resulted in factor-independent proliferation.62 In addition, among other phenotypes, the Stat5A/B gene-targetted mice demonstrate a profound inability to modulate a T-cell response.11 It is possible that constitutive Stat5 activation leads to inappropriate activation of an IL-2 target gene. The crucial role of Stat5 in leukemogenesis may be best evaluated by expressing activated tyrosine kinases into a Stat5-deficient background to determine if the lack of Stat5 expression affects the latency of leukemogenic oncogenes such as BCR-ABL or TEL-JAK2.

Patients harbouring TEL translocations to activated tyrosine kinases, including TEL-PDGF-Rβ,20 TEL-ABL,18,19 and TEL-JAK2,21,22 have been reported. Unlike TEL-AML1 translocations, which constitute 20% to 30% of pediatric ALL cases,63 64 fusion of TEL to activated tyrosine kinases appears to be a rather infrequent event. We have examined a cytogenetic database consisting of 10,350 patients that have been observed at several Toronto hospitals since 1986 and have discovered no evidence for additional TEL-JAK2 [t(9;12)(p24;p13)] translocations.

These studies were initiated to develop a model to examine constitutive Jak2 activation. During the course of this research, two groups have demonstrated that TEL-Jak2 chromosomal translocations do occur.21,22 To date, 3 patients have been described: 2 with pediatric ALL who express TEL-JAK2 fusions21,22 and a third patient with atypical CML or CMML who has a compound translocation resulting in the fusion of one allele of TEL to EVI165 and the other allele forming a TEL-JAK2 fusion.21 In the former case, the two translocations generate a fusion protein containing the JH1 domain, whereas in the latter case, a chimeric product fuses the JH2 and JH1 domains of Jak2 to TEL. In this study, we have generated two activated fusion proteins: TEL-Jak2 JH1 (which is missing the TEL exon 5 sequence and 33 amino acids from one of the observed ALL products) and TEL-Jak2 JH2+JH1 (which is missing 37 amino acids from the CMML translocation). The constructs described in this study express exons 1-4 of TEL. Both TEL-ABL18,19 and TEL-JAK221 22 translocations have been described with either exons 1-4 or exons 1-5 of TEL. It is apparent that the TEL exon 5 sequence does not play a direct role in affecting transformation. Therefore, we feel confident that these fusions are representative of two of the previously reported TEL-JAK2 fusions.

Targets of TEL-Jak2 other than the Stat proteins remain to be identified. Recent studies have shown the critical importance of Jak2 in the development of the myeloid lineage.2 Interestingly, Stat5 does not appear to be essential for the development of these hematopoietic lineages.11 This suggests that Jak2 is required for the activation of other Stats or unique transcription, cell cycle, or apoptotic targets necessary to promote differentiation of myeloid cells. Thus, deregulated Jak2 activity may result in the inappropriate or prolonged activation of these downstream targets. Expression of TEL-Jak2 in a hematopoietic background such as Ba/F3 cells allows us to delineate between normal cytokine-regulated and deregulated Jak2 signaling pathways.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Gary Gilliland and Martin Carroll for ongoing discussion and support and Mark Wong and Eleanor Fish for assistance with EMSA experiments. We appreciate helpful comments on the manuscript from Jane McGlade, Sonya Penfold, and members of the Barber laboratory.

J.M.-Y.H. and B.K.B. contributed equally to this work.

Supported by Medical Research Council MT-13612, the Cancer Research Society, Inc, and the University of Toronto Connaught New Staff Matching Grant. D.L.B. is a Special Fellow of the Leukemia Society of America.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Dwayne L. Barber, PhD, Ontario Cancer Institute, Division of Cellular and Molecular Biology, 610 University Ave, Toronto, Ontario, M5G 2M9, Canada; e-mail:dbarber@oci.utoronto.ca.