Abstract

The synthetic retinoid 6-[3-adamantyl-4-hydroxyphenyl]-2-naphthalene carboxylic acid (CD437), which was originally developed as an retinoic acid receptor (RAR)-γ agonist, induces rapid apoptosis in all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA)-sensitive and ATRA-resistant clones of the NB4 cell line, a widely used experimental model of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL). In addition, the compound is apoptogenic in primary cultures of freshly isolated APL blasts obtained from a newly diagnosed case and an ATRA-resistant relapsed patient. NB4 cells in the S-phase of the cycle are most sensitive to CD437-triggered apoptosis. CD437-dependent apoptosis does not require de novo protein synthesis and activation of RAR-γ or any of the other nuclear retinoic acid receptors. The process is preceded by rapid activation of a caspase-like enzymatic activity capable of cleaving the fluorogenic DEVD but not the fluorogenic YVAD tetrapeptide. Increased caspase activity correlates with caspase-3 and caspase-7 activation. Inhibition of caspases by z-VAD suppresses the nuclear DNA degradation observed in NB4 cells treated with CD437, as well as the degradation of pro–caspase-3 and pro–caspase-7. CD437-dependent activation of caspases is preceded by release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria into the cytosol of treated cells. Leakage of cytochrome c lays upstream of caspase activation, because the phenomenon is left unaffected by pretreatment of NB4 cells with z-VAD. Treatment of APL cells with CD437 is associated with a caspase-dependent degradation of promyelocytic leukemia-RAR-, which can be completely inhibited by z-VAD.

ACUTE PROMYELOCYTIC leukemia (APL) is a rare disease representing approximately 10% to 15% of all the acute myelogenous leukemias in the adult.1 APL is associated with a typical chromosomal translocation, which results in the synthesis of an aberrant form of the retinoic acid receptor RAR-α, known as promyelocytic leukemia (PML)–RAR-α.2PML–RAR-α is thought to play a crucial role in the clonal expansion and the differentiation block along the granulocytic pathway observed in the APL blast.2 Paradoxically, in spite of the derangement of the major form of RAR present in the hematopoietic system, the APL blast is exquisitely sensitive to the antiproliferative and cytodifferentiating action of all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA).3,4 The retinoid is extremely powerful in inducing granulocytic maturation of APL blasts in vitro.5 This cytodifferentiating effect is also observed in vivo and explains the efficacy of ATRA in the clinical management of APL.3

In vitro, ATRA-dependent granulocytic maturation of APL blasts is followed by a slow6 and relatively inefficient7process of apoptosis or programmed cell death (PCD),* which seems to be PML–RAR-α– or RAR-α–mediated.8 Furthermore, ATRA-induced apoptosis is entirely dependent on granulocytic maturation, as it is not observed in ATRA-resistant APL cell lines9,10 and freshly isolated leukemic cells obtained from ATRA-insensitive relapsed patients.11 These may be two important reasons as to why ATRA alone cannot eradicate the leukemic cells and current therapeutic protocols are based on combinations between ATRA and chemotherapeutic agents.12,13 The long time required for the completion of the apoptotic process set in motion by ATRA and the relative inefficiency of this retinoid in inducing apoptosis may be related to the fact that APL cells have prolonged cell survival,14 which is likely to be the consequence of the expression of the PML–RAR-α protein.15 Because apoptosis is probably the main modality by which leukemic cells are cleared from the body following treatment with pharmacologically active agents, the identification of new retinoid molecules inducing PCD in PML–RAR-α–expressing cells could be an important goal in APL therapy. The availability of new retinoids or combinations of retinoids that accelerate the process of apoptosis and/or render it granulocytic-maturation–independent would be advantageous in the setting of the first- and second-line clinical treatment of APL.

CD437 (6-[3-adamantyl-4-hydroxyphenyl]-2-naphthalene carboxylic acid) is a promising synthetic molecule, which seems to represent the prototype of a new class of retinoids with strong apoptogenic properties. The compound, which was originally developed as an RAR-γ–selective agonist,16 has recently been reported to induce apoptosis in human mammary carcinoma,17,18melanoma,19,20 and myeloid21 cell lines in vitro. The spectrum of CD437 activity may not be limited to these types of neoplasia and is likely to extend to other kinds of cancer and leukemia.22-25 In vivo preclinical studies indicate that the compound is well tolerated at the doses that show antitumor activity.19 All this prompted us to investigate the in vitro effects of CD437 on APL cells and to study the underlying mechanisms of action. In NB4 cells and primary cultures of APL blasts, the compound is capable of inducing a granulocytic maturation– and nuclear receptor–independent process of apoptosis. Apoptosis does not require de novo protein synthesis and is accompanied by degradation of PML–RAR-α. The process is associated with activation of caspases, an expanding family of cysteine proteases that play an important role in the execution phase of PCD triggered by various stimuli.26Activation of caspase-3 and caspase-7 seems to be of pivotal importance in CD437-induced apoptosis, a process that can be completely blocked by specific and cell-permeable caspase inhibitors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

The RAR-γ agonists 6-[3-adamantyl-4-hydroxyphenyl]-2-naphthalene carboxylic acid (CD437), CD232527 and CD2781, the pan-RAR reverse agonist CD3106 (AGN193109),28 the pan-RXR antagonist CD3159 (LG100754),29 and the RAR-β,γ antagonist CD266530 were synthesized by GALDERMA Research and Development (Sophia Antipolis, France). ATRA was purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Stock solutions of retinoids in dimethylsulfoxide (10−2 mol/L) were kept in aliquots at −80°C protected from the light until use.

Cell Culture and Treatment

The NB4 cell line31 was obtained from Dr Michel Lanotte (Unité INSERM 301, Hopital St Louis, Paris, France), and the ATRA-resistant NB4.30632,33 cell clone was provided by Dr Carlo Passerini-Gambacorti (Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori di Milano, Italy). PR9 and MT8 cells were obtained from Dr Pier Giuseppe Pelicci (Istituto Oncologico Europeo, Milano, Italy), and U937 cells were from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Rockville, MD). The cell lines were free from mycoplasma contamination, as assessed by staining with Hoechst 33258. Freshly isolated APL cells were obtained from the bone marrow of two APL patient as already described34-37 following informed consent and were characterized for the presence of the typical t(15:17) chromosomal translocation and for the expression of the PML–RAR-α transcript. Cell lines and freshly isolated cells were cultured in the presence of RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS).

Cell Viability, Apoptosis, and Determination of DEVD-amc Hydrolytic Activity

Cell viability was determined by counting the percentage of red/white cells in Burker chambers following staining with erythrosin (Sigma). For the determination of the apoptotic index, cells were fixed under methanol and stained with 4′-6-diamidine-2-phenylindole (DAPI).38 Following extensive washing in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), slides were scored in double-blind under the fluorescence microscope. The apoptotic index represents the percentage of fragmented nuclei and was determined on a microscopic field of at least 400 cells/each experimental point.

For the determination of DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity, cells (1 × 106) were resuspended in 100 μL of lysis buffer (10 mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.4; 0.1% CHAPS; 2 mmol/L EDTA; 2mmol/L dithiothreitol [DTT]). Following determination of the protein content by the Bradford method,39 a volume equivalent to 3 μg of proteins (generally 1 to 3 μL) was incubated in 500 μL of reaction buffer (20 mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.4, 10% [vol/vol] glycerol, 2 mmol/L DTT, and 20 μmol/L DEVD-amc [Peptide Co, Osaka, Japan]) in the dark at 37°C for 2 hours. At the end of the incubation time, reactions were stopped by the addition of 500 μL of the same reaction buffer without DEVD-amc. Samples were read in a Kontron spectrophotofluorometer (Kontron Instruments, Milano, Italy) at an excitation wavelength of 380 nm and an emission wavelength of 460 nm.40

Tdt-Mediated dUTP Nick End-Labeling (TUNEL) Assay

The TUNEL assay was performed with a commercially available kit according to the instructions of the manufacturer (In situ cell detection kit, Fluorescein; Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany). Briefly, 2 × 106 control and treated NB4 cells were obtained, fixed in 70% ethanol/saline, washed in PBS, and resuspended in 0.1% Triton X-100 in sodium citrate. Following incubation and staining with the components of the kit, the cell suspension was analyzed by flow cytometry using the FacSort system (Becton Dickinson, Sunnyvale, CA).

DNA Fragmentation

Diphenylamine assay.

Cells (1 × 106) were centrifuged in 1.5-mL tubes at 13,000g for 2 minutes, washed with cold PBS, and lysed with 10 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.5, 1 mmol/L EDTA, and 0.2% Triton X-100. After incubation on ice for 15 minutes, low– and high–molecular weight DNA (DNA from apoptotic and nonapoptotic cells) was separated by centrifugation at 13,000g at 4°C for 20 minutes. Centrifugation-resistant, low–molecular weight DNA in the supernatant was precipitated with 12.5% (vol/vol) trichloro acetic acid (TCA) for 18 hours,41 and pellets were resuspended in 300 μL cold 12.5% TCA. Samples were then centrifuged at 13,000g at 4°C for 5 minutes, and DNA in the precipitates was extracted with 20 μL 5 mmol/L NaOH and 20 μL 1 mol/L perchloric acid at 70°C for 20 minutes. Subsequently, 120 μL diphenylamine reagent (Sigma) was added and the samples were incubated at 37°C for 18 hours. From each sample, 120 μL was transferred to flat-bottomed 96-well plates and absorbance at 600 nm was measured on an automated plate reader (Titertek Multiskan, Flow ICN, Milano, Italy). Fragmentation was calculated as the percentage of total DNA (supernatant and pellet) recovered as low–molecular weight DNA in the supernatant.41

DNA electrophoresis.

Cells (1 × 106) were centrifuged in 1.5 mL tubes at 13,000g for 2 minutes, washed with cold PBS, and lysed in 0.5 mL hypotonic buffer (10 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.4, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 0.2% Triton X-100) for 15 minutes on ice. Lysates were centrifuged at 13,000g at 4°C for 20 minutes. Pellets containing high–molecular weight DNA were mixed with 0.4 mL 10 mmol/L EDTA, 50 mmol/L Tris, 0.5% N-lauryl-sarcosine, and 0.5 μg/mL proteinase K and were incubated at 48°C for 18 hours. Centrifugation-resistant low–molecular weight DNA was incubated with 20 μg/mL RNase at 37°C for 1 hour. Low– and high–molecular weight DNA were extracted with phenol/chloroform (1:1, vol/vol), precipitated with 0.5 mol/L NaCl and 1 vol propanol, resuspended in water, mixed with loading buffer (2.5% Ficoll, 0.025% bromophenol blue, and 0.025% xylene cyanol), heated at 75°C for 5 minutes, and electrophoresed in 1% agarose containing 1 μg/mL ethidium bromide.41

Cell Kinetics

To obtain a distinct evaluation of the cell cycle perturbations, exponentially growing NB4 cells were treated for 15 minutes with 20 μmol/L bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU). At the end of the incubation with BrdU, the medium was removed and cells were washed twice in PBS and treated for various amounts of time with CD437. After treatment, the drug-containing medium was removed, and the cells were washed twice with PBS and fixed in 70% ethanol. For the detection of BrdU incorporation into DNA, the fixed cells were washed with cold PBS and the DNA was denatured with 1 mL of 2 mol/L HCl for 20 minutes at room temperature. DNA denaturation was stopped by addition of 3 mL of 0.1 mol/L sodium tetraborate, pH 8.5. Following centrifugation, the pellet was incubated with 1 mL of 0.5% Tween-20 (Sigma) in PBS and 1% normal goat serum (Dako, Copenhagen, Denmark) for 15 minutes at room temperature. Incorporated BrdU was visualized by incubation with an anti-BrdU monoclonal antibody (MoAb; Becton Dickinson) diluted 1:10 in 0.5% Tween-20 in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark. Following centrifugation, the pellet was incubated with 1 mL of 0.5% Tween-20 and 1% NGS for 15 minutes at room temperature. This was followed by incubation with a fluorescent fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated F(ab′)2fragment of a goat anti-mouse IgG MoAb (Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories Inc, West Grove, PA) diluted 1:50 in 0.5% Tween-20 in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark. The cell pellet was finally resuspended in 2 mL of a PBS solution containing 2.5 μg/mL propidium iodide and 25 μg/mL RNAse (Boehringer) and stained overnight at 4°C in the dark. Monoparametric DNA and biparametric BrdU/DNA analyses were performed on at least 20,000 cells for each sample with the FacSort system (Becton Dickinson), and the data were analyzed with the Cell Quest software (Becton Dickinson). The fluorescence pulses were detected using a band pass 530 ± 30 nm and 620 ± 35 nm filter for the green and red fluorescence, respectively, in combination with a dichroic 570-nm mirror.

Intracellular Cytochrome c Redistribution

Cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions from NB4 cells were obtained essentially as described by Pastorino et al,42 the major difference being represented by the initial homogenization buffer and the added ultracentrifugation step at 100,000g. Briefly, approximately 4 × 106 cells per each experimental point were washed twice in PBS and the pellet was resuspended in 5 mL of ice-cold buffer (20 mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.5/1.5 mmol/L MgCl2/10 mmol/L KCl/1 mmol/L EDTA/1 mmol/L EGTA/1 mmol/L DTT/0.1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride/10 μg/mL leupeptin, aprotinin, and pepstatin A, 250 mmol/L sucrose). Cells were homogenized with 30 strokes of a teflon/glass potter until disruption of the cells, as assessed under the microscope. An aliquot of the homogenate (approximately 5%) was kept for the determination of the total amount of cytochrome c (cyt c) and for the determination of DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity. The remainder of the homogenate was centrifuged at 2,500g to eliminate nuclei and cell debris. The supernatant was centrifuged at 12,000g to sediment the microsomal fraction. The supernatant of this centrifugation was further centrifuged at 100,000g for 1 hour to obtain the cytosolic fraction, which was filtered through 0.2-μm Ultrafree MC filters (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The total homogenate and the two subcellular fractions were stored at −80°C until use.

Western Blot Analysis

For Western blot analysis, total cellular extracts from NB4 (approximately 3 × 106) were prepared at 4°C in 50 μL of suspension buffer containing 0.1 mol/L NaCl, 10 mmol/L Tris/HCl (pH 7.6), 1 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mg/mL aprotinin, 1 mg/mL leupeptin, 2.5 mg/mL soybean trypsin inhibitor, and 100 mg/mL phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride (all from Sigma). The cells were lysed by adding 50 μL of lysis buffer containing 100 mmol/L Tris/HCl (pH 6.8), 200 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 0.2% bromophenol blue, and 20% glycerol. Samples were then boiled for 10 minutes, sonicated, and centrifuged. Aliquots of the supernatants were fractionated by electrophoresis on 10% SDS acrylamide gel and electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membranes, blocked with 5% nonfat powdered milk in TBS-T (20 mmol/L Tris/HCl [pH 7.6], 137 mmol/L NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20) and then incubated for 2 hours at 37°C with commercially available rabbit polyclonal antibodies recognizing caspase-1 (ICE p10 [C-20], raised against a peptide corresponding to the carboxyl terminus of the caspase-1 precursor of human origin; cat no. sc-515), caspase-2 (ICH-1S/L[H-19], raised against a peptide corresponding to the amino terminus of the caspase-2 precursor of human origin; cat no. sc-623), caspase-3 (CPP32 p20 [N-19], raised against a peptide corresponding to the amino terminus of the p20 subunit of the caspase-3 precursor of human origin; cat no. sc-1226), caspase-4 (TX p20 [N-15], raised against a peptide corresponding to amino acids 95-109 mapping at the amino terminus of the p20 subunit of the caspase-4 precursor of human origin; cat no. sc-1229), caspase-10 (Mch4 p20 [C-16], raised against a peptide corresponding to the carboxyl terminus of the caspase-10 precursor of human origin; cat no. sc-6185), poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP; PARP [N-20], raised against a peptide corresponding to amino acids 1-20 of the amino terminus of the protein of human origin; cat no. sc-1561; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and caspase-7 (generated by immunizing rabbits with the synthetic peptide KPDRSSFVPSLFSKKKKN, corresponding to the amino terminal portion of the putative p20 subunit of caspase-7)43 (a kind gift of Dr Marta Muzio, Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri, Milano). Following extensive washing with TBS-T, the blots were incubated for 90 minutes with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG. After a brief rinsing with TBS-T, immunoreactive protein bands were visualized with a chemiluminescence-based procedure using the ECL detection kit (Amersham, Little Chalfont, UK) according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from NB4 cells as already described.34-37 Single-strand DNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA with reverse transcriptase (RT) and PCR amplified using couples of amplimers specific for the various caspase isoenzymes and for actin using a commercially available kit (Perkin Elmer, Norwalk, CT). The following amplimers were used: pro–caspase-1 (GenBank acc. No. X65019) 5′GGGTACAGCGTAGATGTGAAAAAAAATCTCACTGCTTCG3′ (nucleotide 596-634), 5′GCCCATTGTGGGATGTCTCCAAGAA3′ (complementary to nucleotide 1021-1045); pro–caspase-2 (GenBank acc. no. U13022), 5′GTGCACTTCACTGGAGAGAAA3′ (nucleotide 617-637), 5′GGGCAGTCTCATCTTCGGCAA3′ (complementary to nucleotide 1113-1133); pro–caspase-3 (GenBank acc. no. U13737), 5′AAGGTATCCATGGAGAACACTGAAAAC3′ (nucleotide 216-242), 5′AACCACCAACCAACCATTTCT3′ (complementary to nucleotide 1059-1079); pro–caspase-4 (GenBank acc. no. U28014), 5′CAGAGCACAAGTCCTCTGACA3′ (nucleotide 621-641), 5′AGGGCTGGGCTGCTTGTG3′ (complementary to nucleotide 1182-1199); pro–caspase-6 (GenBank acc. no. U20536), 5′CCGGCAGGTGGGGAAGAAAA3′ (nucleotide 112-131), 5′TGCAACAGAGTAACACATGAGGAAGTC3′ (complementary to nucleotide 691-717); pro–caspase-7 (GenBank acc. no. U37449), 5′GGGCTGTATTGAAGAGCAGC3′ (nucleotide 161-179), 5′GATCTGCATGATTTCCAGGT3′ (complementary to nucleotide 877-895); pro–caspase-8 (GenBank acc. no. U60520), 5′TAAACACTAGAAAGGAGGAGATGGAAAGGGAACT3′ (nucleotide 492-525), 5′CATGGGAGAGGATACAGCAGATGAAGCA3′ (complementary to nucleotide 1232-1259); pro–caspase-10 (GenBank acc. no. U60519), 5′ATGGGAGATTTGGAGCTGTC3′ (nucleotide 1091-1110), 5′TTAGTGTGAAAGCAGGCTGG3′ (complementary to nucleotide 1511-1530); β-actin,445′GCGCTCGTCGTCGACAACGG3′ (nucleotide 60-79), 5′GATAGCAACGTACATGGCTG3′ (complementary to nucleotide 430-449). These amplimers have already been described by Martins et al,45 and their use results in specific amplification products. PCR reactions were initiated under hot start conditions and continued for a total of 30 cycles under step-cycle conditions on Perkin-Elmer 9600 DNA thermal cycler using 95°C (45 seconds) for denaturation, 54°C (45 seconds) for annealing, and 72°C (60 seconds) for extension. At the end of the reaction one tenth of the sample was run on a 1.2% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide.

RESULTS

The Synthetic Retinoid CD437 Is Apoptogenic in NB4 Cells and Causes Rapid Activation of a Caspase-Like Activity

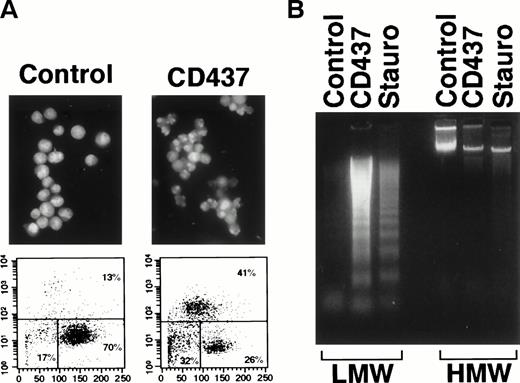

Treatment of the APL-derived NB4 cell line for 16 hours with CD437 (10−6 mol/L)16 results in the appearance of a large number of cells presenting typical signs of apoptosis or PCD, upon May-Grunwald-Giemsa staining (data not shown). The morphology of NB4 apoptotic cells includes membrane blebbing, cytoplasmic shrinking, and nuclear fragmentation. This last feature is highlighted by staining with the fluorogenic substrate DAPI and by flow cytometric analysis, following application of the TUNEL assay46(Fig 1A). In the experiment presented, the TUNEL assay shows that CD437 increases, by approximately threefold (41% v 13%), the number of cells showing signs of DNA fragmentation. Agarose gel electrophoresis of DNA isolated from NB4 cells treated with CD437 shows the typical internucleosomal fragmentation ladder observed during apoptosis (Fig 1B). The level of DNA fragmentation caused by CD437 is of the same order of magnitude as that observed after treatment with staurosporine, a classical and robust apoptogenic stimulus.

Apoptotic effects of CD437 on NB4 cells. NB4 cells (200,000/mL) were treated with vehicle alone (DMSO, Control), CD437 (10−6 mol/L), or Staurosporine (Stauro, 10−6 mol/L) for 16 hours. (A) Fluorescence microphotographs of DAPI-stained cells (original magnification × 40) are shown in the top two panels. The bottom panels show flow cytometric TUNEL analyses with forward scatter on the horizontal axis and fluorescence intensity on the vertical axis. The percentage of apoptotic, necrotic, and viable cells is indicated on the top-right, bottom-left, and bottom-right, respectively. (B) Intranucleosomal DNA fragmentation, as assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis. LMW, centrifugation-resistant low–molecular weight DNA; HMW, high–molecular weight DNA.

Apoptotic effects of CD437 on NB4 cells. NB4 cells (200,000/mL) were treated with vehicle alone (DMSO, Control), CD437 (10−6 mol/L), or Staurosporine (Stauro, 10−6 mol/L) for 16 hours. (A) Fluorescence microphotographs of DAPI-stained cells (original magnification × 40) are shown in the top two panels. The bottom panels show flow cytometric TUNEL analyses with forward scatter on the horizontal axis and fluorescence intensity on the vertical axis. The percentage of apoptotic, necrotic, and viable cells is indicated on the top-right, bottom-left, and bottom-right, respectively. (B) Intranucleosomal DNA fragmentation, as assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis. LMW, centrifugation-resistant low–molecular weight DNA; HMW, high–molecular weight DNA.

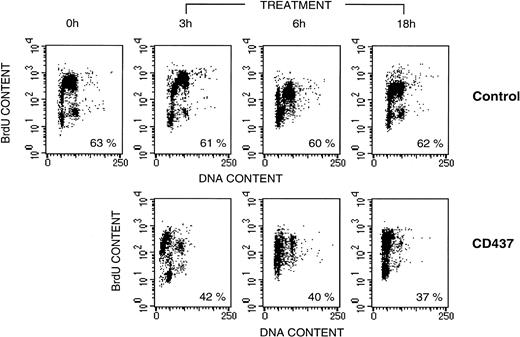

To investigate whether CD437 has any effect on the cell cycle and whether apoptosis is phase-specific, we pulse-labeled NB4 cells with BrdU, a pyrimidine analog that is incorporated into DNA (Fig 2). In control conditions, approximately 60% of the cells are in S-phase and become labeled with BrdU. The length of the NB4 cell cycle is approximately 18 hours, as calculated by the time intervening between two successive S-phases. The number and the proportion of BrdU-labeled cells does not significantly change within the time frame of our experiment. Treatment of cells with CD437 for 3 hours is associated with a lower percentage of BrdU-positive cells (approximately 40%), suggesting early death of a proprtion of cells in the S-phase of the cycle. At the same time point, CD437 causes the appearance of a detectable proportion (22%) of BrdU-labeled cells with a hypodiploid content of DNA (presumably apoptotic cells). At 6 and 18 hours, the percentage of BrdU-positive and hypodiploid cells has increased to 26% and 46%, respectively. By 18 hours, the BrdU-negative cells and the remaining BrdU-positive cells are blocked in G1 or are hypodiploid. Taken together, the results suggest that NB4 cells in the S-phase of the cycle are the ones that are most susceptible to the apoptogenic effects of CD437.

NB4 cell kinetics following treatment with CD437. NB4 cells were seeded at 200,000/mL in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS, allowed to enter the exponential phase of growth by incubation for 12 hours in the same medium. Subsequently cells were pulse-labeled with BrdU for 15 minutes as described in Materials and Methods before incubation with vehicle (DMSO), alone (Control), or with 10−6 mol/L CD437 for the indicated amount of time. Cells were analyzed for the content of DNA following staining with propidium iodide (horizontal axis) or for the amount of BrdU incorporated into DNA (vertical axis) by flow cytometry. Numbers below each panel indicate the percentage of BrdU-positive cells.

NB4 cell kinetics following treatment with CD437. NB4 cells were seeded at 200,000/mL in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS, allowed to enter the exponential phase of growth by incubation for 12 hours in the same medium. Subsequently cells were pulse-labeled with BrdU for 15 minutes as described in Materials and Methods before incubation with vehicle (DMSO), alone (Control), or with 10−6 mol/L CD437 for the indicated amount of time. Cells were analyzed for the content of DNA following staining with propidium iodide (horizontal axis) or for the amount of BrdU incorporated into DNA (vertical axis) by flow cytometry. Numbers below each panel indicate the percentage of BrdU-positive cells.

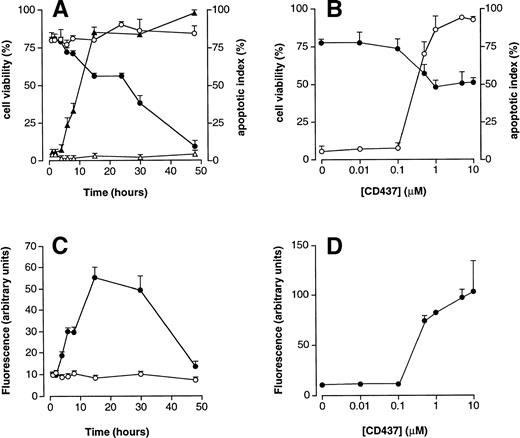

PCD is the major mechanism by which CD437 causes cell demise (Fig 3A). In fact, before undergoing death, the majority of the cells in culture (approximately 80% at 15 hours) present signs of nuclear fragmentation and apoptosis. Cells showing clear signs of nuclear fragmentation by DAPI staining start to be evident following 2 hours of treatment and reach a plateau at 15 hours. This is followed by a progressive decrease in the number of viable cells that completely disappear from the culture by 48 hours. The concentration curve for the apoptogenic effects of CD437 is shown in Fig 3B, along with the effects of the retinoid on the percentage of viable cells in culture. Following 16 hours of treatment, CD437 is maximally apoptogenic at 10−6 mol/L with a calculated EC50 of approximately 3 × 10-7 mol/L. Apoptosis is accompanied by activation of caspases, as assessed by an increase in DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity (Fig 3C), whereas YVAD-amc hydrolytic activity is barely detectable in untreated NB4 cells and is left unaffected by CD437 (data not shown). Considering that DEVD is a relatively specific substrate for caspase-3–like proteases (caspase-2, caspase-3, caspase-6, and caspase-7), whereas YVAD is recognized predominantly by caspase-1,47 our data indicate that CD437 activates the first type of proteolytic enzymes. The time course of caspase activation parallels that of DNA fragmentation, although a dramatic drop in DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity caused by cell distruction is observed between 30 and 48 hours of treatment. The EC50 of CD437 for the increase in DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity in NB4 cell extracts (Fig 3D) is very similar to that causing a 50% reduction in cell viability and half-maximal increase in the number of apoptotic cells. Taken together, our data indicate that CD437-dependent apoptosis, loss of cell viability, and caspase activation are three strictly related processes.

Effects of CD437 on NB4 cell viability, apoptosis, and DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity. (A) NB4 cells (300,000/mL) were treated for the indicated amount of time with vehicle (DMSO, open symbols) or with 10−6 mol/L CD437 (solid symbols). Circles indicate the percentage of viable cells (erythrosin staining), whereas triangles indicate the percentage of apoptotic cells (DAPI staining). (B) NB4 cells (300,000/mL) were treated for 16 hours with the indicated concentration of CD437. Solid circles indicate the percentage of viable cells, whereas open circles indicate the percentage of apoptotic cells. (C and D) Extracts from the cells of the experiments presented in (A) and (B), respectively, were assayed for DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity. Open circles represent extracts from vehicle-treated cells, whereas solid circles represent CD437-treated cells. Results are the mean ± SD of three separate culture dishes.

Effects of CD437 on NB4 cell viability, apoptosis, and DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity. (A) NB4 cells (300,000/mL) were treated for the indicated amount of time with vehicle (DMSO, open symbols) or with 10−6 mol/L CD437 (solid symbols). Circles indicate the percentage of viable cells (erythrosin staining), whereas triangles indicate the percentage of apoptotic cells (DAPI staining). (B) NB4 cells (300,000/mL) were treated for 16 hours with the indicated concentration of CD437. Solid circles indicate the percentage of viable cells, whereas open circles indicate the percentage of apoptotic cells. (C and D) Extracts from the cells of the experiments presented in (A) and (B), respectively, were assayed for DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity. Open circles represent extracts from vehicle-treated cells, whereas solid circles represent CD437-treated cells. Results are the mean ± SD of three separate culture dishes.

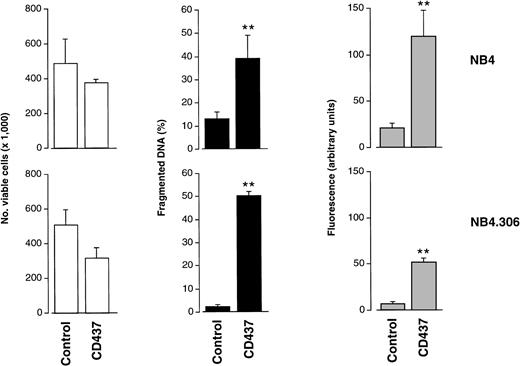

The Apoptogenic Effects of CD437 Are Independent of Retinoic Acid Sensitivity

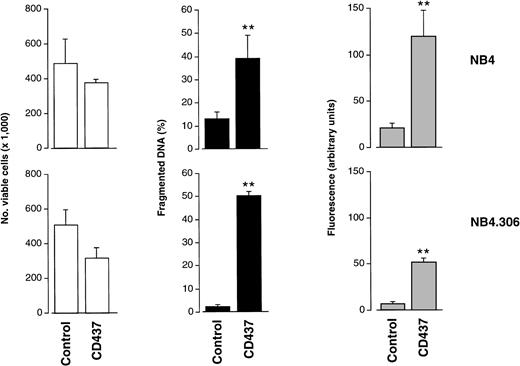

The apoptogenic effects of CD437 are independent of cell sensitivity to ATRA (Fig 4). After 10 hours of treatment at a concentration of 10−6 mol/L, the retinoid causes similar levels of nuclear fragmentation and apoptosis in both NB4 cells and the ATRA-resistant NB4.306 cell line.32 Consistent with the results in Fig 3, at this early time point, there is only a slight decrease in cell viability; however, at later time points the kinetics of cell demise in the two cell lines are similar (data not shown). Even in the case of NB4.306 cells, CD437-induced apoptosis is associated with the appearance of DEVD-amc but not YVAD-amc hydrolytic activity (data not shown). This suggests that the effector phase of the apoptotic process triggered by CD437 in both NB4 and NB4.306 cells is likely to be regulated by the same type of caspase isoenzymes. This is supported by the fact that the two cell lines express the same complement of caspases in basal conditions (see Fig 7 and data not shown).

Effects of CD437 on viability, DNA fragmentation, and DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity in the ATRA-resistant NB4.306 cell line. NB4 or NB4.306 cells (300,000/mL) were treated for 10 hours with vehicle (DMSO, Control) or with 10−6 mol/L CD437. At the end of the treatment cells were obtained and processed for analysis. White columns indicate the number of viable cells (erythrosin staining), black columns indicate the amount of fragmented DNA (diphenylamine assay), and shaded columns indicate DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity. Results are the mean ± SD of three separate culture dishes.

Effects of CD437 on viability, DNA fragmentation, and DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity in the ATRA-resistant NB4.306 cell line. NB4 or NB4.306 cells (300,000/mL) were treated for 10 hours with vehicle (DMSO, Control) or with 10−6 mol/L CD437. At the end of the treatment cells were obtained and processed for analysis. White columns indicate the number of viable cells (erythrosin staining), black columns indicate the amount of fragmented DNA (diphenylamine assay), and shaded columns indicate DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity. Results are the mean ± SD of three separate culture dishes.

CD437 Induces Caspase Activity and Cell Death in Freshly Isolated APL Cells

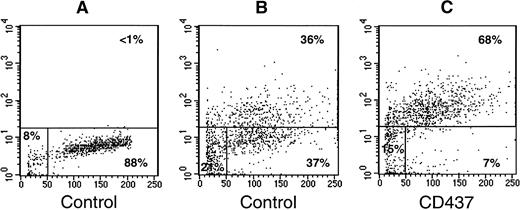

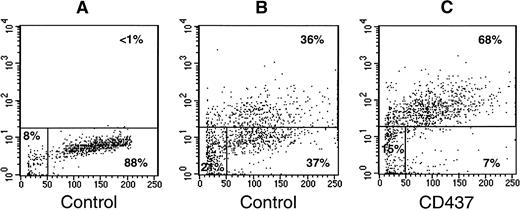

To support the significance of the results obtained in the NB4 model, we evaluated the ability of CD437 to cause in vitro cell death and to induce activation of caspases in freshly isolated blasts obtained from two APL patients representing a newly diagnosed case (patient 1) and an ATRA-resistant relapsed case (patient 2; Table 1). In both cultures, exposure of blasts to CD437 (10−6 mol/L) for 16 hours does not result in a significant decrease in the number of viable cells relative to control conditions. Following 68 hours, treatment of blasts from patient 1 with the retinoid results in a remarkable decrease in the number of viable cells. A similar effect is also observed in blasts from patient 2, although, in this case, it is necessary to slightly protract the exposure time to CD437 to observe a significant diminution in the number of viable cells. Noticeably, exposure of cells from patient 2 to ATRA (10−6 mol/L) for the same amount of time has no effect on the number of cells or viability relative to control conditions (data not shown). In patient 1, an increase in DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity is evident 68 hours after challenge with CD437, whereas in patient 2, caspase activation is already observed at 16 hours and is maintained, albeit at slightly lower levels at least until 60 hours (fluorescence arbitrary units: CD437 = 6.2 ± 0.2, control = 2.5 ± 0.7; mean ± SD of three replicates), decreasing to almost background levels by 84 hours (Table 1). Although we could not get a quantitative assessment of the degree of nuclear fragmentation in the blasts from patient 1, we performed a TUNEL assay on the cells obtained from patient 2 (Fig5). Following 60 hours of treatment, CD437 causes a significant increase in the percentage of TUNEL positive blasts relative to what is observed in blasts maintained in medium containing vehicle alone (68% v 36%). Taken together, the results show that primary cultures of APL blasts are responsive to CD437 regardless of their in vivo sensitivity to ATRA. Furthermore, our data are consistent with the fact that a bona fide process of apoptosis is responsible for at least part of the cytocidal effect of CD437 in cultures of freshly isolated APL cells. Finally, relative to what is observed for NB4 blasts, the longer exposure time necessary to cause cell demise in primary cultures of APL promyelocytes is probably due to the very low proliferation rate typical of these cells in standard culture conditions.

CD437-dependent apoptosis in primary cultures of freshly isolated APL blasts, as assessed by the TUNEL assay. Freshly isolated APL blasts (300,000/mL) from patient 2 (Table 1) were treated with vehicle (DMSO), alone (Control; A and B), or with CD437 (10−6 mol/L; C) for 60 hours. The panels show flow cytometric TUNEL analyses with forward scatter on the horizontal axis and fluorescence intensity on the vertical axis. (A) Negative control for the TUNEL assay, showing the level of background fluorescence in samples treated with fluorescent dUTP in the absence of TdT. The results shown were obtained on an aliquot of the control culture, but similar results were obtained on an aliquot of the CD437 culture (not shown). The percentage of apoptotic, necrotic, and viable cells is indicated on the top-right, bottom-left, and bottom-right, respectively.

CD437-dependent apoptosis in primary cultures of freshly isolated APL blasts, as assessed by the TUNEL assay. Freshly isolated APL blasts (300,000/mL) from patient 2 (Table 1) were treated with vehicle (DMSO), alone (Control; A and B), or with CD437 (10−6 mol/L; C) for 60 hours. The panels show flow cytometric TUNEL analyses with forward scatter on the horizontal axis and fluorescence intensity on the vertical axis. (A) Negative control for the TUNEL assay, showing the level of background fluorescence in samples treated with fluorescent dUTP in the absence of TdT. The results shown were obtained on an aliquot of the control culture, but similar results were obtained on an aliquot of the CD437 culture (not shown). The percentage of apoptotic, necrotic, and viable cells is indicated on the top-right, bottom-left, and bottom-right, respectively.

Apoptosis and Induction of Caspase Activity by CD437 Are Receptor-Independent Events and Do Not Require De Novo Protein Synthesis

To verify whether the strong apoptogenic activity of CD437 is a peculiarity of this compound or is a feature observed in other RAR-γ–selective agonists, the effect of this retinoid on NB4 cells was compared with that of CD2325 and CD2781 (Table 2). These two selective RAR-γ agonists were chosen because the affinity of CD2325 and CD2781 for RAR-γ (Ki of 53 nmol/L and 76 nmol/L, respectively) is not different from that of CD437 (77 nmol/L). In addition, the transactivation potential of the three compounds on RAR-γ is similar (EC50: CD437, 7 nmol/L; CD2325, 12 nmol/L; CD2781, 20 nmol/L). When cells were treated for 16 hours at a concentration of 10−6 mol/L, CD437 is more apoptogenic than CD2325, whereas CD2781 does not cause any sign of apoptosis, at this concentration or at any of the concentrations tested (Table 2 and data not shown). Thus, apoptosis is not related to the binding affinity or transactivation potential of the three compounds for RAR-γ. The degree of apoptosis triggered by CD437 and CD2325 is quantitatively correlated with the level of induction of DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity. This indicates that caspase activation is fundamental for the apoptogenic activity of both CD437 and CD2325.

Although CD437, CD2325, and CD2781 are selective agonists of RAR-γ, they show residual transactivating activity in the presence of RAR-α and RAR-β. In addition, binding of the three compounds to RXRs has not been studied in detail. Thus, it is possible that the apoptogenic activity of CD437 is mediated by activation of any of these retinoic acid receptors. However, the effects of CD437 on NB4 cells are not due to activation of RARs or RXRs (Table 3). In fact, challenge of the promyelocytic blasts with the pan-RAR reverse agonist CD3106, the RAR-β,γ selective antagonist CD2665, or the RXR antagonist CD3159 has no effect on the level of nuclear fragmentation and caspase activation observed following treatment of NB4 cells with CD437 for 6 hours. At the 10:1 molar ratio of antagonist/agonist used, CD3106, CD2665, and CD3159 readily block the transactivation of RAR-α, RAR-γ, and RXR-α by their respective agonists AM580, CD437, and 9-cis retinoic acid in transient transfection assays performed in COS-7 cells using appropriate reporter constructs (data not shown). Furthermore, the pan-RAR antagonist CD3106 completely blunts the cytodifferentiating and growth inhibitory effects of AM580 or ATRA in NB4 cells (E.G., unpublished results, January 1998).

In various biological systems, the process of apoptosis requires de novo protein synthesis and is blocked by protein synthesis inhibitors, such as cycloheximide (CHX). In addition, in melanoma cells,19 CD437 has been shown to increase the AP1 transcriptional complex, which can trigger apoptosis in certain conditions. On the other hand, drug-induced apoptosis has been reported to occur in the presence of protein synthesis inhibitors.48 49 For all these reasons, we tested the effects of CHX on CD437-dependent PCD in NB4 cells (Table 4). In our experimental conditions, CHX inhibits protein synthesis by more than 90% and is not toxic. Pretreatment of cells for 2 hours with CHX before addition of CD437 has only minimal effects on the number of apoptotic cells present in the culture following 6 hours of treatment with the retinoid. Similarly, the protein synthesis inhibitor does not affect the level of caspase activation observed in the presence of CD437. These data indicate that de novo protein synthesis is not necessary to produce caspase activation and subsequent apoptosis.

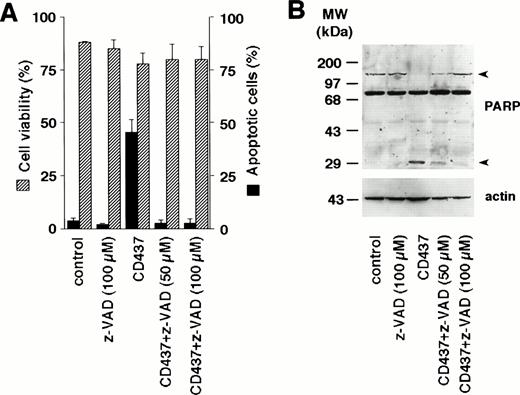

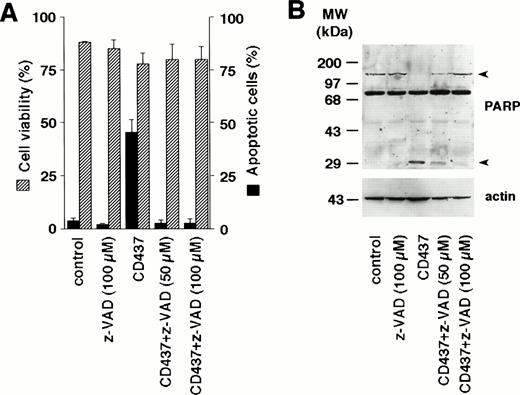

Inhibition of Caspases Blocks CD437-Induced Apoptosis

As CD437 causes a rapid increase in DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity, we investigated the effects of Z-Val-Ala-DL-Asp-fluoromethylketone (z-VAD), a general inhibitor of caspases, on CD437-induced apoptosis in NB4 cells (Fig 6A). At the two concentrations used (50 and 100 μmol/L), challenge of NB4 blasts for 6 hours with z-VAD alone does not change the number of cells showing signs of apoptosis. However, the caspase inhibitor completely blunts the appearance of apoptotic cells following treatment with CD437. Suppression of the apoptotic process is the consequence of specific caspase inhibition, as shown by the Western blot experiment conducted with antibodies recognizing PARP, a substrate protein specific for various caspase isoenzymes (Fig 6B). PARP is rapidly cleaved by CD437 into two fragments of approximately 80 and 30 kD (only the latter fragment is evident in our blot, as the 80-kD proteolytic fragment of PARP is masked by a nonspecific band). Cotreatment with CD437 and z-VAD results in a dose-dependent decrease in the amount of the 30-kD proteolytic fragment. The CD437-dependent cleavage of PARP is also partially blocked by the inhibitor of caspase-3–like enzymes, DEVD-cho, whereas it is left totally unaffected by the caspase-1 inhibitor YVAD-cho (data not shown). This further supports the concept that CD437 causes activation of caspase-3 and/or caspase-3–like proteolytic activity.

Inhibition of apoptosis and PARP cleavage by the caspase inhibitor z-VAD in NB4 cells. NB4 cells (300,000/mL) were treated for 6 hours with vehicle (DMSO, Control) or with 10−6 mol/L CD437 following pretreatment for 2 hours in the presence or absence of the indicated concentration of z-VAD. (A) Dashed columns indicate the percentage of viable cells (erythrosin staining), whereas solid columns indicate the percentage of apoptotic cells (DAPI staining). Results are the mean ± SD of three separate culture dishes. (B) Extracts from cells treated as in (A) were subjected to Western blot analysis using an anti-PARP–specific antibody. Filters were reprobed with actin to ensure that similar amounts of protein were loaded in each lane. Arrowheads on the right indicate the position of the PARP intact protein and one of its proteolytic fragments. The molecular weight of protein standards is indicated on the left. The results were replicated in a separate experiment.

Inhibition of apoptosis and PARP cleavage by the caspase inhibitor z-VAD in NB4 cells. NB4 cells (300,000/mL) were treated for 6 hours with vehicle (DMSO, Control) or with 10−6 mol/L CD437 following pretreatment for 2 hours in the presence or absence of the indicated concentration of z-VAD. (A) Dashed columns indicate the percentage of viable cells (erythrosin staining), whereas solid columns indicate the percentage of apoptotic cells (DAPI staining). Results are the mean ± SD of three separate culture dishes. (B) Extracts from cells treated as in (A) were subjected to Western blot analysis using an anti-PARP–specific antibody. Filters were reprobed with actin to ensure that similar amounts of protein were loaded in each lane. Arrowheads on the right indicate the position of the PARP intact protein and one of its proteolytic fragments. The molecular weight of protein standards is indicated on the left. The results were replicated in a separate experiment.

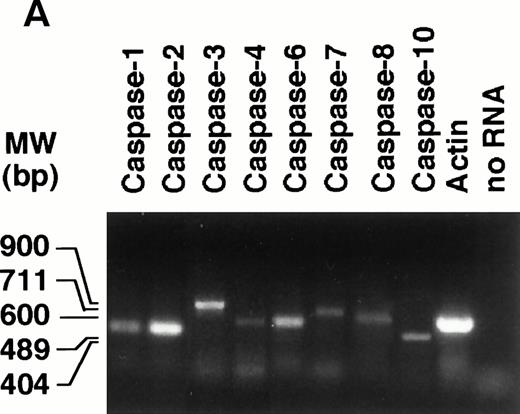

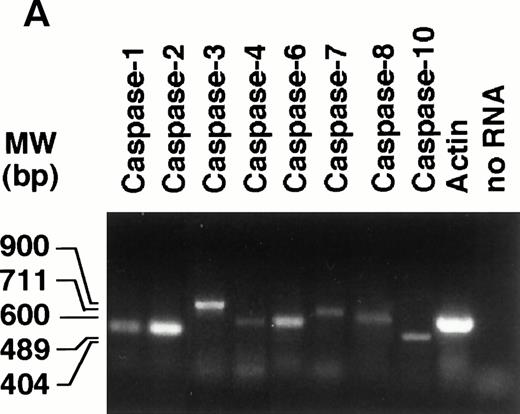

CD437 Causes Degradation of Various Types of Caspase Precursors

To gain insight into the type(s) of caspase responsible for the elevation of DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity in NB4 cell extracts treated with CD437, we first studied the profile of expression of the mRNAs coding for 8 of the 11 known members of the caspase family by RT-PCR. Undifferentiated NB4 cells express transcripts coding for all the members of the caspase family taken into consideration (Fig 7A). The amounts of caspase mRNAs are left unaffected by treatment with CD437 for 6 hours (data not shown). Expression at the mRNA level is generally accompanied by synthesis of the respective precursor protein, as assessed by Western blot analysis performed with available antibodies (Fig 7B). Treatment of NB4 cells with CD437 (10−6 mol/L) for 2 hours results in the prompt disappearance of pro–caspase-1 and in a dramatic reduction in the levels of pro–caspase-7, whereas the kinetics of degradation of pro–caspase-3 is relatively slower. Although a slight degradation of pro–caspase-2 is observed in the experiment presented, in most experiments, the effect is barely detectable and of minor significance. The amounts of pro–caspase-4 and -10 are not affected by CD437 challenge.

Expression of caspase mRNA and proteins in untreated and CD437-treated NB4 cells. NB4 cells (300,000/mL) were grown in basal conditions (A) and treated for the indicated amount of time (B) with vehicle (DMSO, Control) or with 10−6 mol/L CD437. (A) One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed and PCR amplified with couple of amplimers specific for the indicated caspase cDNAs or for actin cDNA. One tenth of the PCR reaction mixture was run on a 1.2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. Appropriate blanks reverse transcribed in the absence of RNA (no RNA) were set up for each RT-PCR reaction; only the blank corresponding to actin is shown. The molecular weight of DNA standards is indicated on the left. (B) Aliquots of the NB4 homogenates containing an equivalent amount of protein were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies specific for the indicated caspases or for actin. The molecular weight of protein standards is indicated on the left. The data are representative of those obtained in three separate experiments.

Expression of caspase mRNA and proteins in untreated and CD437-treated NB4 cells. NB4 cells (300,000/mL) were grown in basal conditions (A) and treated for the indicated amount of time (B) with vehicle (DMSO, Control) or with 10−6 mol/L CD437. (A) One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed and PCR amplified with couple of amplimers specific for the indicated caspase cDNAs or for actin cDNA. One tenth of the PCR reaction mixture was run on a 1.2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. Appropriate blanks reverse transcribed in the absence of RNA (no RNA) were set up for each RT-PCR reaction; only the blank corresponding to actin is shown. The molecular weight of DNA standards is indicated on the left. (B) Aliquots of the NB4 homogenates containing an equivalent amount of protein were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies specific for the indicated caspases or for actin. The molecular weight of protein standards is indicated on the left. The data are representative of those obtained in three separate experiments.

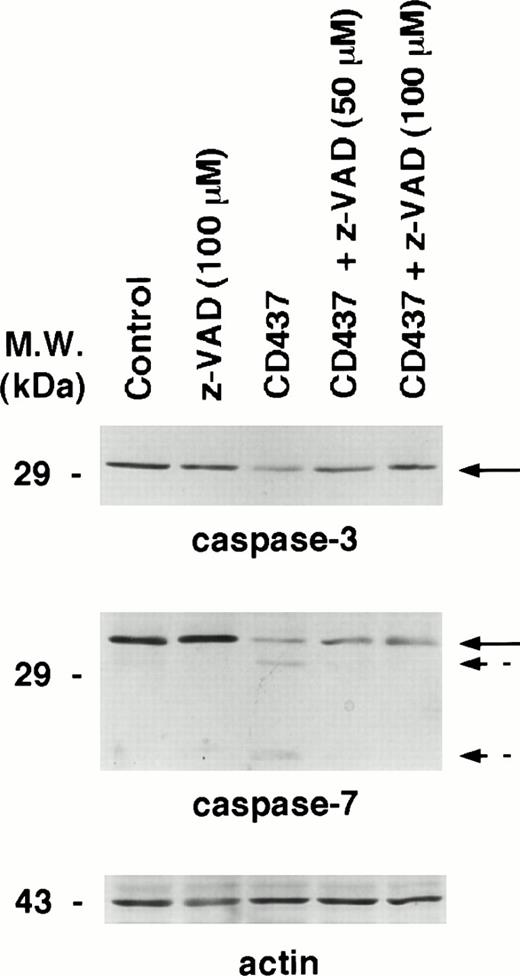

Activation of caspases is accompanied by the appearance of two specific proteolytic bands corresponding to the large and small subunit of the catalitically active enzyme.47,50 The process is blocked by caspase inhibitors, as cleavage of individual caspases is an autocatalytic process or is triggered by other members of the caspase family in a cascade fashion.47 50 To establish whether CD437-dependent degradation of pro–caspase-3 and pro–caspase-7 is accompanied by activation of the two enzymes, we performed the Western blot experiments presented in Fig 8. The data obtained confirm that treatment of NB4 cells with CD437 for 6 hours results in the degradation of pro–caspase-3. Although z-VAD pretreatment does not have any effect on the basal level of the precursor protein, the compound dose-dependently inhibits degradation of pro–caspase-3. However, in our experimental conditions, we were not able to document the presence of specific caspase-3 proteolytic fragments (data not shown). This may be related to the particular type of antibody used in our experiments or to the very short half-life of the activated form of caspase-3 in NB4 cells. In the case of caspase-7, CD437 treatment of NB4 cells results in the appearance of two bands whose apparent molecular weight is consistent with the large and small subunits of the active enzymatic form. In addition, pretretreatment of NB4 cells with z-VAD results in the disappearance of the two degradation bands.

Effect of the caspase inhibitor z-VAD on the degradation of caspase-3 and caspase-7 in CD437-treated NB4 cells. NB4 cells (300,000/mL) were treated for 6 hours with vehicle (DMSO, Control) and with 10−6 mol/L CD437 following 2 hours preincubation in the absence or in the presence of the indicated concentration of z-VAD. Aliquots of the NB4 homogenates containing an equivalent amount of protein were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies specific for caspase-3, caspase-7, and for actin. Solid arrows indicate the position of the band corresponding to pro–caspase-3 and pro–caspase-7, whereas broken arrows indicate the bands corresponding to the large and small subunit of activated caspase-7. The molecular weight of protein standards is indicated on the left. The results were replicated in a separate experiment.

Effect of the caspase inhibitor z-VAD on the degradation of caspase-3 and caspase-7 in CD437-treated NB4 cells. NB4 cells (300,000/mL) were treated for 6 hours with vehicle (DMSO, Control) and with 10−6 mol/L CD437 following 2 hours preincubation in the absence or in the presence of the indicated concentration of z-VAD. Aliquots of the NB4 homogenates containing an equivalent amount of protein were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies specific for caspase-3, caspase-7, and for actin. Solid arrows indicate the position of the band corresponding to pro–caspase-3 and pro–caspase-7, whereas broken arrows indicate the bands corresponding to the large and small subunit of activated caspase-7. The molecular weight of protein standards is indicated on the left. The results were replicated in a separate experiment.

Taken together the data indicate that caspase-3 and caspase-7 are activated upon treatment of NB4 cells with CD437. In addition, they suggest that the two enzyme are responsible for the appearance of DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity observed upon treatment with CD437. In fact, DEVD-amc is a good substrate for caspase-3 and caspase-7, but a poor substrate for caspase-1.

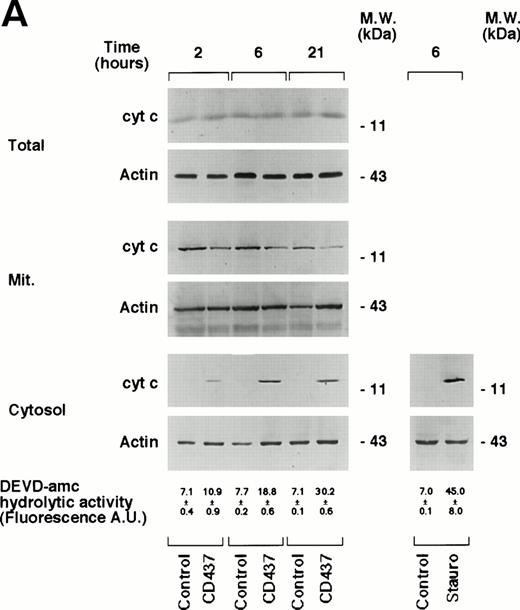

CD437 Induces Release of Cytochrome c From the Mitochondria Into the Cytosol: The Phenomenon Accompanies Caspase Activation and Is Caspase-Independent

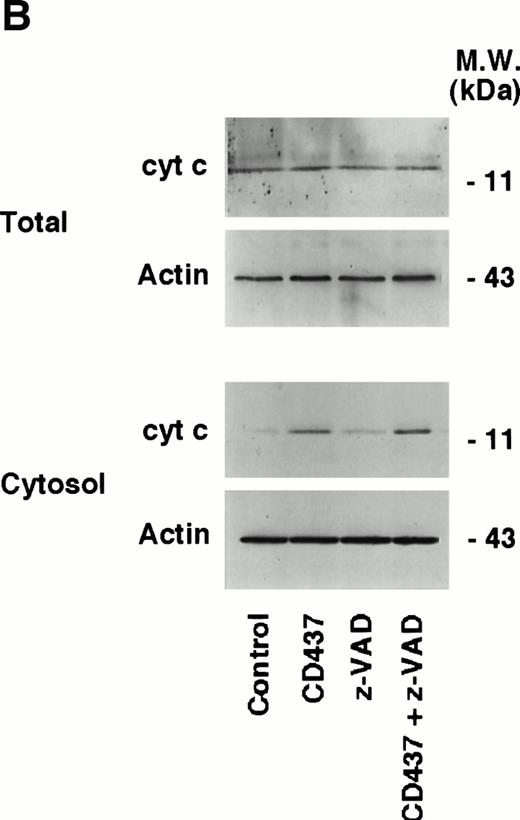

Activation of caspases can be triggered by different types of mechanisms, which are dependent on the type of apoptotic stimulus considered.50 Release of cyt c from the mitochondria into the cytosol results in activation of caspases and apoptosis.51 52 Thus, the subcellular localization of this protein was investigated in NB4 cells grown for various amounts of time in the absence or presence of CD437 (Fig 9A). The total intracellular pool of cyt c observed in control conditions is left unaffected by CD437, as assessed by Western blot analysis of unfractionated NB4 cell extracts. Only trace amounts of cyt c (visible on longer exposures of the films) are present in the cytoplasm of cells grown in control conditions, and these background levels are probably due to leakage from the mitochondria during the process of subcellular fractionation. Treatment of NB4 promyelocytes with CD437 results in a significant increase in the levels of cytoplasmic cyt c. Release into the cytoplasm is accompanied by a decrease in the amount of cyt c associated with the mitochondria, which is consistent with a redistribution of the protein in the two intracellular compartments. The redistribution of cyt c from the mitochondria to the cytoplasm is a relatively rapid event, being observed already following 2 hours of challenge with the retinoid and gradually increasing thereafter. The phenomenon accompanies the increase in DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity, and it is of the same order of magnitude as that observed in the presence of apoptogenic concentrations of staurosporine. To examine whether cyt c release from the mitochondria is affected by caspases, we evaluated the effects of z-VAD on the process (Fig 9B). Until 6 hours of treatment, z-VAD has no effect on the intracellular levels of cyt c observed in the absence or in the presence of CD437. In addition, the caspase inhibitor does not significantly affect the redistribution of cyt c into the cytosol observed in the presence of the retinoid. These data indicate that the leakage of cyt c from the mitochondria is independent of caspase activation.

Intracellular redistribution of cyt c in NB4 cells following treatment with CD437. (A) NB4 cells (300,000/mL) were treated for the indicated amount of time with vehicle (DMSO, Control) and with 10−6 mol/L CD437. Following harvesting and homogenization, a small aliquot of the homogenate was directly processed for Western blot analysis (total) and for the determination of DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity. The remaining amount of homogenate was subjected to differential ultracentrifugation to separate the mitochondrial fraction (Mit.) from the cytosol before Western blot analysis. Aliquots of the various fractions containing an equivalent amount of protein (30 μg) were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies specific for cyt c and actin. The molecular weight of protein standards is indicated on the right. The values of DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity are the mean ± SD of three replicates of the same homogenate. (B) NB4 cells (300,000/mL) were treated for 6 hours with vehicle (DMSO, Control) and with 10−6 mol/L CD437 following 2 hours preincubation in the absence or in the presence of z-VAD (100 μmol/L). Aliquots of the NB4 homogenates (total) or the cytosol fraction as in (A) containing an equivalent amount of protein were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies specific for cyt c and for actin. The molecular weight of protein standards is indicated on the right. The experiments are representative of at least four other experiments giving essentially the same results.

Intracellular redistribution of cyt c in NB4 cells following treatment with CD437. (A) NB4 cells (300,000/mL) were treated for the indicated amount of time with vehicle (DMSO, Control) and with 10−6 mol/L CD437. Following harvesting and homogenization, a small aliquot of the homogenate was directly processed for Western blot analysis (total) and for the determination of DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity. The remaining amount of homogenate was subjected to differential ultracentrifugation to separate the mitochondrial fraction (Mit.) from the cytosol before Western blot analysis. Aliquots of the various fractions containing an equivalent amount of protein (30 μg) were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies specific for cyt c and actin. The molecular weight of protein standards is indicated on the right. The values of DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity are the mean ± SD of three replicates of the same homogenate. (B) NB4 cells (300,000/mL) were treated for 6 hours with vehicle (DMSO, Control) and with 10−6 mol/L CD437 following 2 hours preincubation in the absence or in the presence of z-VAD (100 μmol/L). Aliquots of the NB4 homogenates (total) or the cytosol fraction as in (A) containing an equivalent amount of protein were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies specific for cyt c and for actin. The molecular weight of protein standards is indicated on the right. The experiments are representative of at least four other experiments giving essentially the same results.

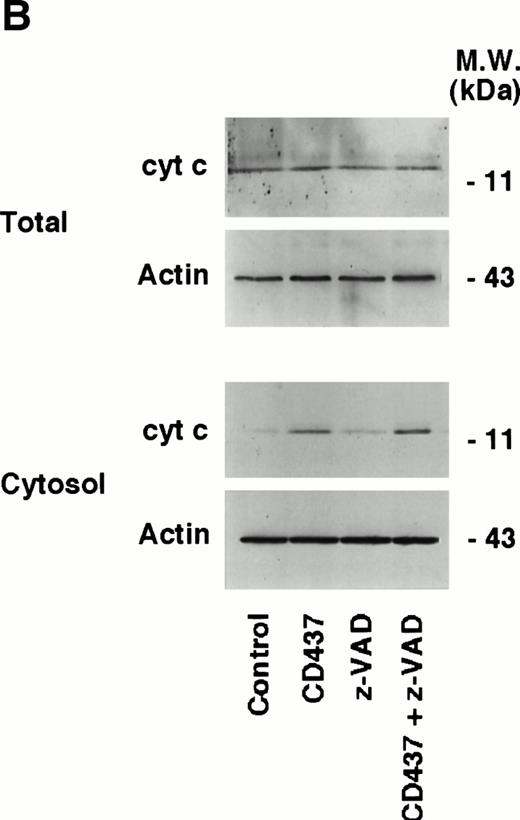

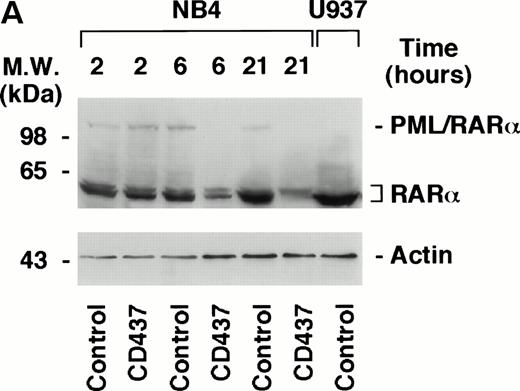

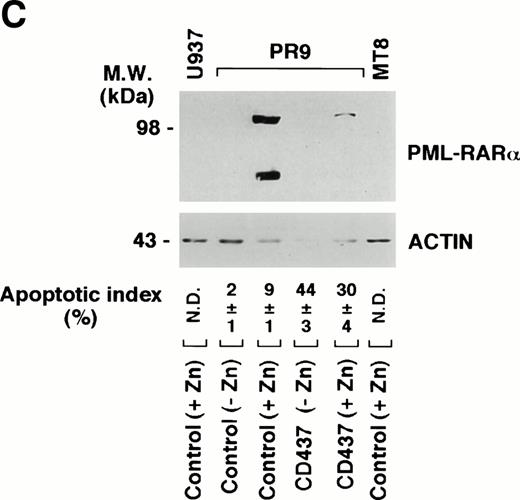

PML–RAR-α Is Degraded by CD437 and Degradation Is Blocked by the Caspase Inhibitor z-VAD

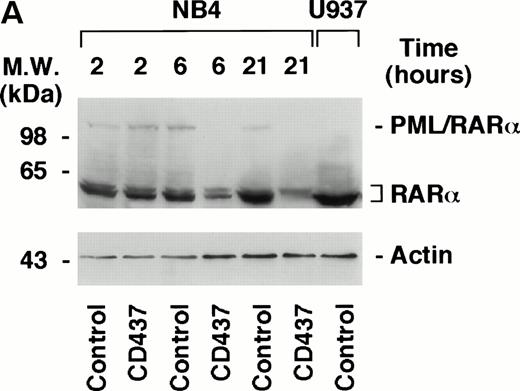

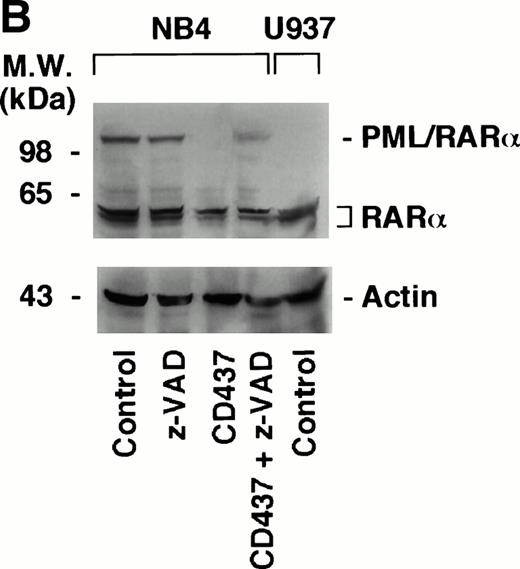

The APL-specific oncogene PML–RAR-α has antiapoptotic activity,14,15 and it has been proposed that the proteasome-dependent degradation of the protein observed following treatment of APL cells with retinoic acid53 and arsenic54 55 may be important for the clinical activity of the two compounds. Because the levels of PML–RAR-α may also be critical in the process of apoptosis triggered by CD437, we were prompted to examine the effects of the retinoid on the protein in the NB4 cell line. Challenge of cells with CD437 for 6 and 21 hours results in the degradation of PML–RAR-α and to a lesser extent of RAR-α as well (Fig 10A). The effect is relatively specific, because the levels of actin are left unaltered by the retinoid. PML–RAR-α and RAR-α degradation is blocked by pretreatment with z-VAD (Fig 10B). This indicates that caspases are directly or indirectly responsible for the proteolytic cleavage of the two receptors.

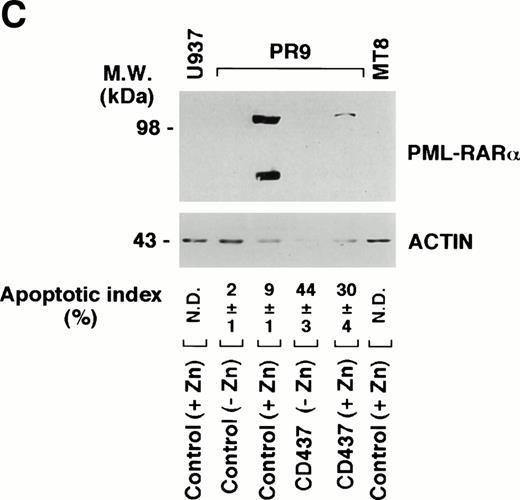

Degradation of PML–RAR- by CD437 in PR9 and NB4 cells. (A) NB4 cells (300,000/mL) were treated for the indicated amount of time with vehicle (DMSO, Control) or with 10−6 mol/L CD437. (B) NB4 cells (300,000/mL) were treated for 6 hours with vehicle (DMSO, Control) or with 10−6 mol/L CD437 following pretreatment for 2 hours in the absence or presence of z-VAD (100 μmol/L). (C) U937, PR9, and MT8 cells (300,000/mL) were treated for 16 hours with vehicle (DMSO, Control) or with 10−6 mol/L CD437 in the presence or absence of zinc sulfate (Zn, 100 μmol/L) as indicated. The percentage of cells showing nuclear fragmentation upon staining with DAPI was scored on parallel cultures. Each value represents the mean ± SD of three replicate cultures. ND, not determined. For Western blot analysis, cells were obtained, homogenized, and aliquots of the homogenate containing an equivalent amount of protein were subjected to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, electrotransfer to nitrocellulose membranes, and incubation with antibodies recognizing human RAR- and human actin (A). Alternatively, blots were sequentially probed with the two antibodies (B and C). The molecular weight of protein standards is indicated on the left. The results were replicated in a separate experiment.

Degradation of PML–RAR- by CD437 in PR9 and NB4 cells. (A) NB4 cells (300,000/mL) were treated for the indicated amount of time with vehicle (DMSO, Control) or with 10−6 mol/L CD437. (B) NB4 cells (300,000/mL) were treated for 6 hours with vehicle (DMSO, Control) or with 10−6 mol/L CD437 following pretreatment for 2 hours in the absence or presence of z-VAD (100 μmol/L). (C) U937, PR9, and MT8 cells (300,000/mL) were treated for 16 hours with vehicle (DMSO, Control) or with 10−6 mol/L CD437 in the presence or absence of zinc sulfate (Zn, 100 μmol/L) as indicated. The percentage of cells showing nuclear fragmentation upon staining with DAPI was scored on parallel cultures. Each value represents the mean ± SD of three replicate cultures. ND, not determined. For Western blot analysis, cells were obtained, homogenized, and aliquots of the homogenate containing an equivalent amount of protein were subjected to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, electrotransfer to nitrocellulose membranes, and incubation with antibodies recognizing human RAR- and human actin (A). Alternatively, blots were sequentially probed with the two antibodies (B and C). The molecular weight of protein standards is indicated on the left. The results were replicated in a separate experiment.

To support the data obtained in NB4 cells in a different model of PML–RAR-α expression, we evaluated degradation of the protein in PR9 cells. This is a U937-derived clone stably transfected with an inducible form of the PML–RAR-α cDNA,14 which expresses elevated amounts of the protein upon induction with zinc sulfate (Zn). As expected, whereas the parental cell line U937 and the MT8 clone (stably transfected with the empty vector) do not express the protein upon treatment with Zn, treatment of PR9 with appropriate concentrations of the metal ion results in the synthesis of PML–RAR-α, which can be easily detected under the form of a 110-kD protein by Western blot analysis (Fig 10C). Challenge of PR9 cells with Zn and CD437 (10−6 mol/L), for 16 hours, results in a dramatic reduction in the levels of the PML–RAR-α protein, which is the consequence of a progressive degradation of the oncogene product, as the levels of the respective transcript do not change significantly in the same experimental conditions (data not shown). Similarly to what observed in NB4 cells, PML–RAR-α degradation in PR9 blasts is accompanied by a remarkable elevation in DEVD-amc–hydrolyzing activity (fluorescence arbitrary units: 45 ± 7 in CD437 + Zn–treated cellsv 10 ± 2 in cells treated with Zn alone) and by the appearance of a significant number of cells showing signs of nuclear fragmentation and apoptosis (Fig 10C).

Taken together the results obtained in NB4 and PR9 cells indicate that CD437-dependent caspase activation, apoptosis, and PML–RAR-α degradation are three strictly related phenomena, regardless of the cellular context taken into consideration.

DISCUSSION

In this article, we report on the apoptogenic effects, in APL cells, of CD437, a new retinoid originally developed as a selective RAR-γ agonist16 and characterized by promising in vitro and in vivo antitumor activity in human and mouse experimental models.19 The compound is devoid of cytodifferentiating activity,36 yet is capable of inducing apoptosis in both ATRA-sensitive and ATRA-resistant APL cells, as shown in the NB4 and NB4.306 models and confirmed in primary cultures of APL blasts. The apoptogenic activity of CD437 in APL cells is not related to the ability of the retinoid to interact with RAR-γ or any of the other retinoic acid receptors belonging to the family of RARs or RXRs. In fact, the RAR-γ mRNA is not expressed at detectable levels in NB4 cells, as assessed by the Northern blot technique.56Furthermore, CD2871, another RAR-γ agonist with binding and trans-activating activity for the receptor similar to that of CD437, is completely incapable of inducing apoptosis in NB4 cells. Finally, specific pan-RAR; RAR-β,γ; and pan-RXR antagonists or reverse agonists do not inhibit CD437-dependent apoptosis.

CD437-induced apoptosis is mediated by caspases, a growing family of proteases involved in the effector phase of various types of PCD.47,50 In fact, CD437 induces caspase activity and caspase inhibitors delay the process. A DEVD-amc caspase-type hydrolytic activity is rapidly increased by the retinoid, and the cell-permeable caspase inhibitor z-VAD affords complete protection from CD437-induced NB4 apoptosis. Caspases are enzymes normally present in various cell types under the form of inactive precursor proteins that need to be activated by specific proteolytic cleavage.26,47,50 Often, individual caspases are activated by other members of the caspase family in a cascade fashion. Although NB4 cells express the precursors for at least 6 of the 11 known caspase isoforms, activation of a few selected caspase isoenzymes is likely to be of paramount importance for the appearance of DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity in NB4 cell extracts. First, following treatment with CD437, the levels of the precursors for caspase-4 and caspase-10 are left unaltered. Second, though caspase-1 is the first caspase to disappear from the cytosol of CD437-treated cells, degradation is not associated with activation of the enzyme. In fact, CD437 does not cause the appearance of YVAD-amc hydrolytic activity, which would be expected in case of caspase-1 activation, as the fluorogenic tetrapeptide is a good substrate for the protein.47 At present we cannot rule out a role for caspase-2, although degradation of this enzyme is not dramatic and is just appreaciable in some experiments. By contrast, degradation of the caspase-7 and the caspase-3 precursors is likely to be associated with activation of the two enzymes. The active forms of these two proteases are probably responsible for the appearance of DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity in the cytosol of CD437-treated NB4 cells. In addition, activation of caspase-3 and caspase-7 is likely to be important for the effector phase of the apoptotic process triggered by CD437, since these two isoenzymes, as well as caspase-6, have been implicated in other types of drug-induced apoptosis in leukemia cell.45 57-59 Proteolytic cleavage and activation of caspase-3 and caspase-7 are either the consequence of an autocatalytic process or are the result of the activity of another caspase. As caspase-3 and caspase-7 can cleave each other, it would be important to establish the order of activation of the two enzymes. However, based on the kinetics of cleavage of the precursor, it seems that activation of caspase-7 precedes the activation of caspase-3 (see Fig 7B). Nevertheless, it is important to notice that CD437 acts on caspase isoenzymes that are different from those involved in the process of PCD induced by ATRA. For instance, whereas caspase-3 is degraded and activated by CD437, we did not observe any sign of degradation or activation of caspase-3 by ATRA (E.G., unpublished results, January 1998). This supports the concept that the apoptogenic and cytotoxic processes triggered by the two retinoids are intrinsically different, which is consistent with the fact that CD437 induces apoptosis also in the ATRA-resistant NB4.306 cell line.

The rapidity by which CD437 induces caspase-like activity and APL cell death suggests that the compound directly activates the effector phase of apoptosis. In NB4 cells, the process of CD437-triggered apoptosis and the associated activation of caspases do not require gene expression and de novo protein synthesis as they are left unaffected by the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide. This indicates that the machinery necessary for the demise of NB4 cells is already present in basal conditions, as observed in other paradigms of PCD,48,49 and the phenomenon is in line with the fact that caspase activation and apoptosis are not mediated by activation of the nuclear retinoic acid receptors. Interestingly Piedrafita et al60 reported that CD437 causes rapid and caspase dependent degradation of the SP1 transcription factor through a pathway that is also cycloheximide-insensitive. Thus, the retinoid either directly activates caspases or sets in motion intracellular second messenger pathways that lead to activation of this type of proteases through posttranslational events. As to the first possibility, in vitro incubation of control cell extracts with CD437 does not result in the appearance of DEVD-amc cleavage (E.G., unpublished results, January 1998), indicating that the compound is not capable of causing direct activation of caspases. As to the second possibility, experiments conducted with inhibitors of intracellular second messanger pathways involved in different types of apoptotic processes are consistent with the following conclusions. Activation of caspases and subsequent apoptosis in NB4 cells are not mediated by an increase in the intracellular levels of toxic oxygen radicals, a purported cause of PCD.61 In fact, the only radical scavanger tested showing protection from CD437 cellular effects is N-acetyl cysteine (NAC). However, the compound acts downstream of caspase activation and through a mechanism which is not related to radical scavenging activity (E.G., unpublished results, March 1998). Similarly, tyrosine kinases do not seem to be activated by CD437, as genistein and erbstatin, two relatively specific inhibitors of this class of kinases, have no effect on the processes of apoptosis and caspase activation observed in NB4 cells following treatment with the retinoid (E.G., unpublished results, January 1998). Furthermore, activation and downregulation of protein kinase C by phorbol esters do not alter the kinetics or the levels of caspase activation and subsequent apoptosis in NB4 cells challenged with CD437 (E.G., unpublished results, January 1998). By contrast, certain types of phosphatases may play a role in NB4 PCD, as shown by the results obtained with calyculin A (Cal), a phosphatase inhibitor acting preferentially on phosphatase 2A. Inhibition of a Cal-dependent phosphatase reduces by approximately 70% the increase in DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity observed in CD437-treated NB4 cells. Interestingly, in the presence of CD437, Cal is partially necrogenic to NB4 cells, suggesting that inhibition of phosphatase 2A may tip the balance between apoptosis and necrosis toward the latter modality of cell death (E.G., unpublished results, March 1998).

Although the intracellular signals leading to caspase activation and apoptosis in APL cells treated with CD437 are still unknown, these very signals influence the activity of the mitochondria and lead to the release of cyt c into the cytosol. Release of cyt c into the cytosol is likely to be responsible for the proteolytic degradation and activation of caspase-3 and caspase-7. In fact, it is known that cyt c, in concert with apoptosis activated factor 1 (apaf1) and caspase-9, triggers specific proteolysis and activation of effector caspases in various models of apoptosis.51 In addition, the release of cyt c from the mitochondria triggered by CD437 in NB4 cells cannot be blocked by the caspase inhibitor z-VAD, at least during the early phase of the process, suggesting that the phenomenon lays upstream of caspase activation. This is similar to what was reported by Kim et al62 for Ara-C–induced release of cyt c. Finally, the kinetics of cyt c release from the mitochondria are consistent with its possible causative role in the appearance of DEVD-amc hydrolytic activity in the cytosol of NB4 cells treated with CD437. At present, it is unknown whether CD437-dependent leakage of cyt c from the mitochondria is the result of an increase in membrane permeability consequent to the opening of the mitochondrial pore complex regulated by members of the Bcl-2 family of proteins63 or is a pore complex–independent process, as recently suggested by Bossy-Wetzel et al64 in other paradigms of cytochrome c release. With respect to this, however, we observed that pretreatment with cyclosporin, a ligand of one of the components of the pore complex and a known inhibitor of mitochondrial permeability transition,63 reduces by approximately 50% CD437-induced apoptosis in NB4 cells. In addition, Hsu et al21 very recently reported that CD437 downregulates expression of Bcl-2 in HL-60 cells.

Because PML–RAR-α is an antiapoptotic protein14,15 and its degradation has been implicated as a possible cause of the therapeutic efficacy of ATRA and arsenic,53,54 we analyzed the effects of CD437 on the protein in NB4 and PR9 cells. Treatment of the NB4 cell line with CD437 results in the degradation of PML–RAR-α and to a minor extent of RAR-α as well. This is similar to what has been observed for arsenic54 and to what has been very recently reported for ATRA.55 The data obtained with z-VAD indicate that the degradation of PML–RAR-α triggered by CD437 is directly or indirectly a caspase-dependent process. At present, we do not know whether PML–RAR-α is a direct target for the activity of caspases or its degradation is the consequence of a caspase-triggered activation of other as yet unknown downstream proteases. With respect to this, there are examples of downstream proteases that can be activated by caspases during the process of apoptosis.65Nevertheless, our data indicate that the receptor can be degraded by CD437 through a pathway that is different from the proteasome-dependent pathway triggered by ATRA.53 As to the role that PML–RAR-α degradation plays in the process of apoptosis triggered by CD437, it is unlikely that disabling of the protein is necessary to induce this type of PCD. First, in NB4 cells, degradation of PML–RAR-α is not observed at 2 hours (E.G., unpublished results, March 1998), a time at which DEVD-hyrolizing activity is not yet induced by CD437 (see Fig 3). Thus, proteolysis of PML–RAR-α seems to accompany rather than preceed caspase activation in NB4 cells. Secondly, disabling of the receptor is blocked by a caspase inhibitor like z-VAD, further supporting the concept that PML–RAR-α degradation lies downstream of the activation of the same caspases that are responsible for the apoptotic process triggered by CD437. Thirdly and more importantly, in PR9 cells, CD437 induces caspase activation and apoptosis also in the absence of PML–RAR-α induction (see Fig10C). In addition, the compound is also active in the NB4.306 cell line that has lost expression of the PML–RAR-α protein.32However, the situation may not be so simple. In fact, in PR9 cells, overexpression of PML–RAR-α obtained by raising the concentration of Zn seems to initially protect from CD437-induced apoptosis (E.G., unpublished results, March 1997). Although caution should be exercised in interpreting the results because of the ability of Zn to inhibit caspase-366 as well as other types of caspases,67 these data are in line with the general antiapoptotic effect of the APL oncogene.2,14,15 68 This antiapoptotic effect seems to be operative also in the case of CD437-induced PCD, although the phenomenon is eventually overcome by the caspase-dependent degradation triggered by the retinoid.

In conclusion, the data reported in this article support the idea that CD437 may find clinical application in the treatment of APL, given a mechanism of action that looks substantially different from that of other retinoids and possibly also of other chemotherapeutic agents. It is possible to envision the use of the compound in association with ATRA in the first-line treatment of APL patients to obtain rapid clearance of ATRA-differentiated APL cells by apoptosis. In addition, CD437 may find application in the second-line treatment of ATRA-resistant APL relapses, as suggested by in vitro activity on blasts obtained from an ATRA-resistant relapsed patient. However, two PML–RAR-α negative myeloid cell lines HL-60 and U937 have been recently proven sensitive to the apoptogenic action of CD437.21 Furthermore, we observed morphological apoptosis and caspase activation in freshly isolated blasts of two AML cases (interestingly one of the two cases analyzed was a chemotherapy-resistant and relapsed patient) and one ALL case treated in vitro with pharmacologically active concentrations of the retinoid (E.G., unpublished results, April 1998). Thus, the therapeutic potential of CD437 is certainly not limited to APL and the compound may be clinically useful for other types of acute myeloid and nonmyeloid leukemia.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr M. Lanotte (Unité INSERM 301, “Genetique cellulaire et moleculaire des leucemies,” Centre G; Hayem, Hopital St Louis, Paris, France) for supplying us with the NB4 acute promyelocytic cell line. We are grateful to Dr Carlo Gambacorti-Passerini (Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Milano) for the kind gift of the ATRA-resistant NB4.306 cell line. We thank Dr Marta Muzio (Istituto “Mario Negri,” Milano) for providing us with the polyclonal antibodies against caspase-7 and Dr Pier Giuseppe Pelicci (Istituto Oncologico Europeo, Milano) for the PR9 cell line. Finally, we are also grateful to Prof S. Garattini, Dr M. Salmona, and Dr Eugenio Erba for the critical reading of the manuscript.

Throughout the text, the terms “apoptosis” and “programmed cell death (PCD)” are used indifferently.

Supported by a grant to E.G. from the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca contro il Cancro (AIRC). I.P. is the recipient of an “Alfredo Leonardi” fellowship.

L.M. and I.P. contributed equally to the results presented in this report.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Enrico Garattini, MD, Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Centro Catullo e Daniela Borgomainerio, Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche “Mario Negri,” via Eritrea, 62, 20157 Milano, Italy; e-mail: egarattini@irfmn.mnegri.it.