Abstract

The ex vivo expansion of hematopoietic progenitors is a promising approach for accelerating the engraftment of recipients, particularly when cord blood (CB) is used as a source of hematopoietic graft. With the aim of defining the in vivo repopulating properties of ex vivo–expanded CB cells, purified CD34+ cells were subjected to ex vivo expansion, and equivalent proportions of fresh and ex vivo–expanded samples were transplanted into irradiated nonobese diabetic (NOD)/severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice. At periodic intervals after transplantation, femoral bone marrow (BM) samples were obtained from NOD/SCID recipients and the kinetics of engraftment evaluated individually. The transplantation of fresh CD34+ cells generated a dose-dependent engraftment of recipients, which was evident in all of the posttransplantation times analyzed (15 to 120 days). When compared with fresh CB, samples stimulated for 6 days with interleukin-3 (IL-3)/IL-6/stem cell factor (SCF) contained increased numbers of hematopoietic progenitors (20-fold increase in colony-forming unit granulocyte-macrophage [CFU-GM]). However, a significant impairment in the short-term repopulation of recipients was associated with the transplantation of the ex vivo–expanded versus the fresh CB cells (CD45+repopulation in NOD/SCIDs BM: 3.7% ± 1.2% v 26.2% ± 5.9%, respectively, at 20 days posttransplantation; P < .005). An impaired short-term engraftment was also observed in mice transplanted with CB cells incubated with IL-11/SCF/FLT-3 ligand (3.5% ± 1.7% of CD45+ cells in femoral BM at 20 days posttransplantation). In contrast to these data, a similar repopulation with the fresh and the ex vivo–expanded cells was observed at later stages posttransplantation. At 120 days, the repopulation of CD45+ and CD45+/CD34+ cells in the femoral BM of recipients ranged between 67.2% to 81.1% and 8.6% to 12.6%, respectively, and no significant differences of engraftment between recipients transplanted with fresh and the ex vivo–expanded samples were found. The analysis of the engrafted CD45+ cells showed that both the fresh and the in vitro–incubated samples were capable of lymphomyeloid reconstitution. Our results suggest that although the ex vivo expansion of CB cells preserves the long-term repopulating ability of the sample, an unexpected delay of engraftment is associated with the transplantation of these manipulated cells.

THE BASIC RESEARCH on the biology of ex vivo expansion is now offering new advances in the field of hematopoietic cell transplantation. Data obtained in mouse models have shown an improved hematologic recovery in recipients transplanted with ex vivo–expanded versus fresh hematopoietic samples.1-5 In these models, the advantages and limitations derived from the transplantation of ex vivo–expanded samples are being progressively defined6 and data from the first clinical protocols already reported.7-11 In oncohematology, the conditions required for the purging of tumor-contaminated grafts during the in vitro incubation process are being dissected, and new promising results have been recently reported.12-15 Finally, in the field of gene therapy, the in vitro incubation with adequate combinations of growth factors is frequently used to facilitate the transduction of the primitive repopulating cells or the selection of the transduced population.16-20

Recent results from clinical cord blood (CB) transplantation have shown that the number of nucleated cells per kilogram is a major factor in the recovery of neutrophil and platelet counts.21 This study, together with others previously reported,22-24 has shown the efficacy of CB grafts for the transplantation of children, although suggested limitations for the transplantation of adults. The possibility of ex vivo expanding the progenitors present in CB grafts is, therefore, an attractive approach that may facilitate the engraftment of adult patients with these samples. To what extent the ex vivo expansion of CB cells will be clinically useful for this purpose and whether this will be a safe procedure for preserving the longevity of the self-renewing hematopoietic stem cells, is still unclear. In this respect some restrictions,25 and even marked failures in the repopulating function of in vitro–incubated long-term repopulating cells (LTRCs) have been reported in mouse hematopoietic grafts.26-28 However, other studies have shown that primitive repopulating cells from mouse bone marrow (BM) can be maintained29,30 and even modestly expanded in culture.31 Moreover, in human ex vivo–expanded CB samples, a modest amplification in the progenitors capable of repopulating nonobese diabetic (NOD)/severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice has been achieved,32 33 something that is consistent with the idea that ex vivo expansion protocols could at least preserve the human LTRCs during the amplification of the more mature progenitors.

Regarding the short-term repopulating ability of ex vivo–expanded grafts, our results with mouse BM indicated that the transplantation of these samples mediates an accelerated engraftment of recipients. Nevertheless, we showed that the speed of the engraftment was significantly below predictions made on the basis of the large granulocyte-macrophage colony-forming unit (CFU-GM) content, which characterizes the incubated grafts.6 Whether a similar conclusion is applicable to human ex vivo–expanded samples is unknown and, therefore, a risk in overestimating the functionality of human ex vivo–expanded grafts was deduced from that study.

The use of the human-NOD/SCID mouse model20 now offers the possibility of analyzing the short-term, as well as the long-term, repopulating ability of human hematopoietic samples in an in vivo experimental system. Therefore, with the aim of comparing the in vivo repopulating properties of fresh and ex vivo–expanded CB cells, we have followed the kinetics and stability of engraftment of NOD/SCID mice transplanted with both types of samples. Data presented in this work are consistent with the idea that the ex vivo expansion of CB is compatible with an overall preservation of their long-term repopulating ability. However, an unexpected delay of engraftment was associated with the transplantation of these ex vivo–expanded samples.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human samples and isolation of CD34+ cells.

Cells were obtained from umbilical CB after a normal full-term delivery and the informed consent of the mother. Samples were collected at dawn and processed during the next 12 hours postpartum. Mononuclear (MN) cells were obtained by layering the blood onto Ficoll-Hypaque (1.077 g/mL; Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden), and centrifuging at 400g for 30 minutes. The interface layer was then collected, washed three times, and resuspended in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (IMDM; GIBCO-BRL, Grand Island, NY). To purify the CD34+ cells, the MN fraction was subjected to immunomagnetic separation using the VarioMACS CD34 progenitor cell isolation kit (Myltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA), following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Briefly, MN were washed and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Fraction V; Sigma, St Louis, MO) and 5 mmol/L EDTA. Cells were incubated first with QBEND-10 antibody (mouse anti-human CD34) (Miltenyi Biotech) in the presence of human IgG as a blocking reagent and then with an anti-mouse antibody coupled with MACS microbeads. Labeled cells were filtered through a 30-μm nylon mesh before loading onto a column installed in the magnetic field. Trapped cells were eluted after the column was removed from the magnet and further depleted of contaminant CD34− cells by a second MACS column passage. The purity of the CD34+population ranged from 95% to 98% as evaluated by flow cytometry using an EPICS Elite ESP analyzer (Coulter, Hialeah, FL). CD34+ cells were cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen, with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS). After thawing, CD34+ cells were diluted 1:1 with human albumin 2.5% (Behring, Hoecht Iberica, Spain) and dextran 40, 5% (Rheomacrodex 10%; Pharmacia Biotech), and maintained at room temperature for 10 minutes. Cells were then diluted with medium and centrifuged at 800g for 15 minutes.34 Freshly isolated CD34+ cells, as well as cells that had been cultured for various time intervals, were phenotyped by flow cytometry as previously described.35 Antibodies used for the cytometric analysis included anti-CD34 labeled with phycoerythrin (PE) and anti-CD38 labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

Animals.

NOD/LtSz-scid/scid (NOD/SCID) mice (deficient in Fc receptors, complement function, natural killer, B-, and T-cell function) were used as recipients of the human hematopoietic cells. Mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). All animals were handled under sterile conditions and maintained under microisolators. Before transplantation, 6- to 8-week-old mice were total body irradiated with 2.5 to 3.0 Gy of x-rays (300 kV, 10 mA; Philips MG-324, Hamburg, Germany).

Ex vivo expansion of CD34+ cells.

Purified CD34+ cells were incubated in 25-cm2tissue culture flasks (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) at 2.5 × 104 cells/mL in IMDM containing 20% FBS (GIBCO Laboratories), recombinant human interleukin-3 (IL-3), IL-6, and stem cell factor (SCF) at a final concentration of 100 ng/mL (all of them kindly provided by Immunex, Seattle, WA). At weekly intervals, cell cultures were diluted with fresh complete medium to reach the initial cell concentration. In some experiments cells were incubated under the same experimental conditions using SCF, FLT-3 Ligand (FL; kindly provided by Immunex), and IL-11 (a kind gift from Genetics Institute, Cambridge, MA). At the indicated time points, cells were collected for performing cytologic and cytometric studies, CFU-GM cultures, and transplantation into NOD/SCID mice.

Cytological analyses and CFU-GM assays.

Fresh CD34+ CB cells and 6-day cultured cells were cytocentrifuged onto slides, fixed in 100% methanol for 10 minutes, dried at room temperature, and stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining solution. CFU-GM colonies were grown in enriched semisolid culture media from StemBio Research SG*1d (a kind gift of StemBio Research, Villejuif, France). The appropriate number of cells was seeded and cultured for 14 days at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere at 5% of CO2 in air.

Analysis of human cell engraftment.

At periodic intervals after transplantation, BM samples were aspirated from one femur by puncture through the knee joint, according to a previously described procedure.36 At the end of the experiments, mice were killed and peripheral blood and spleen were also analyzed by flow cytometry for the presence of human cells. Aliquots of 1 to 5 × 105 cells/tube were stained for 25 minutes at 4°C with anti-human–CD45-FITC (clone HI30, Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) or -PECy5 (Clone J33, Immunotech, Marseille, France) in combination with anti-human–CD34-PE (Anti-HPCA-2; Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry, San Jose, CA), anti-human–CD33-PE (Anti-Leu-M9; Becton Dickinson), or anti-human–CD19-PE (Anti-Leu-12; Becton Dickinson). Thereafter, red blood cells were lysed by adding 2.5 mL of lysis solution (0.155 mol/L NH4Cl + 0.01 mol/L KHCO3 + 10−4mol/L EDTA) and incubation at room temperature for 10 minutes. Cells were then washed in PBA (phosphate-buffered salt solution with 0.1% BSA and 0.01% sodium azide), resuspended in PBA + 2 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI), and analyzed by flow cytometry. For each analysis, a total of 10,000 viable (PI−) cells with appropriate forward scatter (FS)/side scatter (SSC) were collected. As controls of nonspecific staining, cells were labeled with conjugated-nonspecific isotype antibodies. Additionally, cells from nontransplanted NOD/SCID mice were stained with anti-CD45, anti-CD34, anti-CD33, and anti-CD19 antibodies.

Statistics.

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. The significance of differences between groups was determined by using the two-tailed Student’s t-test. The processing and statistical analysis of the data were performed by using the software SPSS V6.1.2. (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Ex vivo expansion of CD34+ CB cells incubated with IL-3/IL-6/SCF.

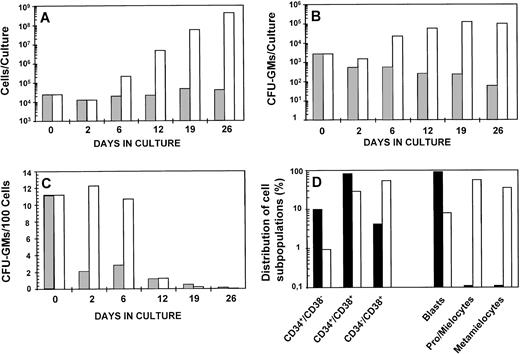

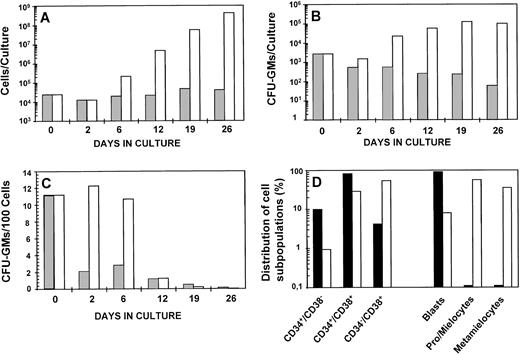

Data in Fig 1 show the kinetics of CD34+ CB cells incubated with or without IL-3/IL-6/SCF as the stimulatory source. As shown in Fig 1A, a progressive amplification in the cellularity of stimulated cultures was observed during the study period. At the end of the incubation, a 17,000-fold increase over input values was observed. The growth of the CFU-GM population reached a plateau on day 19 of incubation, when the number of CFU-GMs generally exceeded 45-fold the input value (Fig 1B). When the proportion of CFU-GMs was evaluated, similar values of CFU-GM/105 cells were observed during the first 6 days in culture (Fig 1C), suggesting a modest differentiation pressure at this time of incubation. A more detailed analysis of the composition of fresh CD34+ cells and 6-day incubated cells is shown in Fig1D, which shows an evident increase in the more differentiated cells (CD34−/CD38+ and morphologicaly differentiated forms) at the expense of a reduced proportion in the primitive precursors (ie, CD34+/CD38− or blast cells). This time of incubation was selected for all the subsequent experiments of transplantation into NOD/SCID mice. The average amplification in cells and CFU-GM at this time was 15.9 ± 3.9-fold and 19.8 ± 7.9-fold, respectively (n = 7).

Ex vivo expansion kinetics of purified CD34+ cord blood cells. Cells were cultured in IMDM supplemented with 20% FBS (▩) or FBS plus IL-3, IL-6, and SCF (□). The figure shows the evolution of the cellularity (A) and CFU-GM (B) of cultures established with an initial input of 2.5 × 104cells; the proportion of CFU-GM along the culture (C), and (D) the total composition of fresh (▪) and 6-day incubated samples in the presence of FBS plus IL-3/IL-6/SCF (□). At weekly intervals, cell cultures were diluted with fresh complete medium to reach the initial cell concentration. The figure represents data obtained from one representative experiment.

Ex vivo expansion kinetics of purified CD34+ cord blood cells. Cells were cultured in IMDM supplemented with 20% FBS (▩) or FBS plus IL-3, IL-6, and SCF (□). The figure shows the evolution of the cellularity (A) and CFU-GM (B) of cultures established with an initial input of 2.5 × 104cells; the proportion of CFU-GM along the culture (C), and (D) the total composition of fresh (▪) and 6-day incubated samples in the presence of FBS plus IL-3/IL-6/SCF (□). At weekly intervals, cell cultures were diluted with fresh complete medium to reach the initial cell concentration. The figure represents data obtained from one representative experiment.

NOD/SCID repopulating ability of ex vivo–expanded grafts.

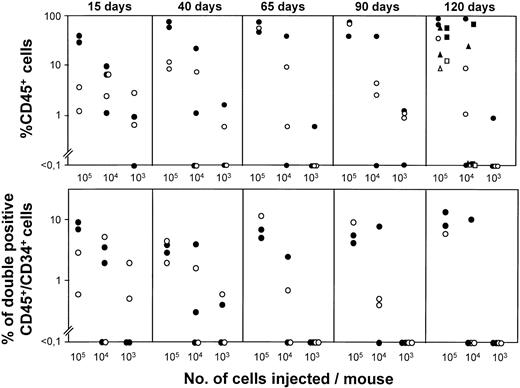

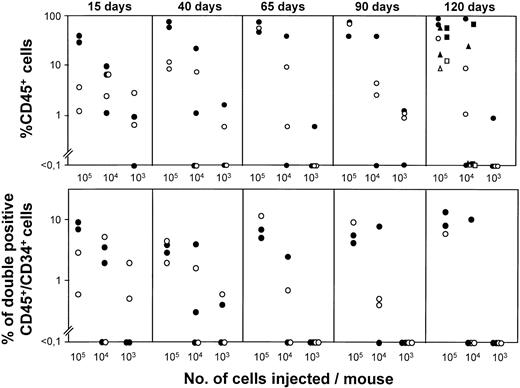

With the aim of evaluating the repopulating properties of ex vivo–expanded versus fresh CB samples, purified CD34+cells were subjected to a 6-day incubation period under the conditions described above. To confirm a relationship between the engraftment level of recipients versus the transplanted cell dose, aliquots consisting of 105, 104, and 103fresh CD34+ cells were transplanted into three groups of NOD/SCID mice. In addition, the populations that corresponded to the incubation of 105, 104, and 103fresh CD34+ cells were transplanted into further groups of irradiated mice. At different times posttransplantation, small samples of BM were obtained from the femora of NOD/SCID recipients, and the proportion of CD45+ and CD45+/CD34+ cells evaluated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis.

As shown in Fig 2, when fresh samples are considered, a good relationship between the size of the transplanted sample and the engraftment of the animals is deduced for all of the posttransplantation periods analyzed, both for CD45+ and CD45+/CD34+ determinations. When ex vivo–expanded samples were transplanted, a dose-dependent engraftment was seen from day 40 to day 120 posttransplantation. At day 15 posttransplantation, however, increases of 10-fold and even 100-fold in the graft size did not significantly modify the modest repopulation associated with the transplantation of 103CD34+ expanded cells.

Cell dose-dependent engraftment of NOD/SCID mice transplanted with fresh or ex vivo–expanded human CD34+ CB cells. The figure represents the proportion of CD45+ and double-positive CD45+/CD34+ cells in the femoral BM of NOD/SCID mice transplanted with 105, 104, and 103 fresh CD34+ CB cells (•) or with the IL-3/IL-6/SCF ex vivo–expanded populations, which corresponded to the incubation of 105, 104, and 103fresh CD34+ cells (○). BM was periodically sampled from day 15 to day 120 posttransplantation. At day 120 posttransplantation, data from spleen (squares), and PB (triangles) are also represented. Samples were ex vivo–expanded with FBS plus IL-3/IL-6/SCF, as indicated in Fig 1.

Cell dose-dependent engraftment of NOD/SCID mice transplanted with fresh or ex vivo–expanded human CD34+ CB cells. The figure represents the proportion of CD45+ and double-positive CD45+/CD34+ cells in the femoral BM of NOD/SCID mice transplanted with 105, 104, and 103 fresh CD34+ CB cells (•) or with the IL-3/IL-6/SCF ex vivo–expanded populations, which corresponded to the incubation of 105, 104, and 103fresh CD34+ cells (○). BM was periodically sampled from day 15 to day 120 posttransplantation. At day 120 posttransplantation, data from spleen (squares), and PB (triangles) are also represented. Samples were ex vivo–expanded with FBS plus IL-3/IL-6/SCF, as indicated in Fig 1.

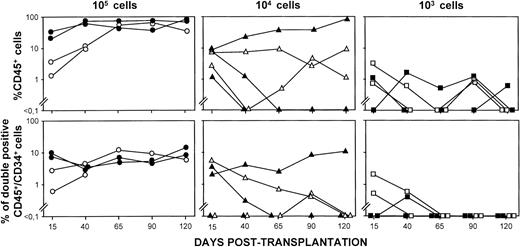

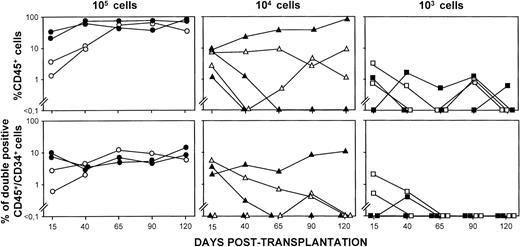

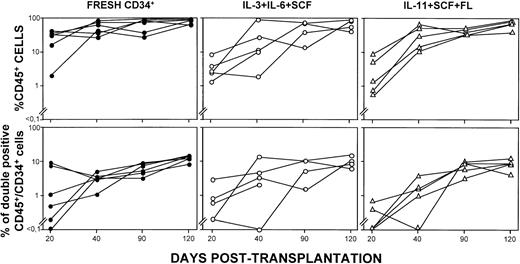

To compare more directly the kinetics of repopulation of fresh and ex vivo–expanded samples, the proportion of CD45+ and CD45+/CD34+ cells corresponding to the individually analyzed mice was represented (Fig 3). The analysis of animals corresponding to the 105 CD34+ cell group shows a gradual increase in CD45+ cells that reached very high and stable values by day 40 posttransplantation. The rate of increase was most significant in mice transplanted with the ex vivo–expanded samples, as the initial values of CD45+ cells in this group were well below the values obtained in the control group. At later stages posttransplantation, high and stable engraftments were also observed in NOD/SCIDs transplanted with the cultured cells. Similar conclusions were deduced from the analysis of the double-positive CD45+/CD34+ cells, although in this case, differences between both groups of recipients were only apparent in the first BM sampling (15 days posttransplantation). When mice were transplanted with smaller grafts, 104 and 103fresh CD34+ cells or the equivalent ex vivo–expanded populations, repopulation differences between the fresh and the ex vivo–expanded grafts could not be established because very heterogeneous and very poor engraftments were observed, respectively.

Kinetics of engraftment of individual NOD/SCID mice transplanted with fresh or ex vivo–expanded CD34+ cells. The figure represents the individual kinetics of engraftment of NOD/SCID mice shown in Fig 2, which were transplanted with fresh (closed symbols) or with the equivalent cell product generated after incubation with IL-3/IL-6/SCF (open symbols). For further details, see legend to Fig 2.

Kinetics of engraftment of individual NOD/SCID mice transplanted with fresh or ex vivo–expanded CD34+ cells. The figure represents the individual kinetics of engraftment of NOD/SCID mice shown in Fig 2, which were transplanted with fresh (closed symbols) or with the equivalent cell product generated after incubation with IL-3/IL-6/SCF (open symbols). For further details, see legend to Fig 2.

With the aim of confirming differences in the engraftment of mice transplanted with fresh and ex vivo–expanded samples, three further experiments were conducted, although in this case, purified CD34+ cells were divided in three aliquots. One aliquot was transplanted before incubation (105 CD34+cells/mouse), while the second and the third ones were previously incubated for 6 days with IL-3/IL-6/SCF and IL-11/SCF/FL, respectively. In these two cases, each recipient was transplanted with the expanded cell product generated by 105 fresh CD34+cells. The average number of cells present in IL-3/IL-6/SCF and IL-11/SCF/FL ex vivo–expanded grafts exceeded 18-fold and 6-fold, respectively, the cell numbers present in the fresh samples. Regarding the CFU-GM content of each of the ex vivo–expanded samples, average increases of 13-fold and 3-fold were obtained, respectively, with respect to the fresh samples (not shown).

Data in Fig 4 show the engraftment of individual NOD/SCIDs transplanted with each of the three populations considered in this new study. The kinetics of engraftment of mice transplanted with fresh CD34+ cells were essentially the same as those described in Fig 3 (see data corresponding to 105 CD34+ cells), although in this case, a heterogeneous repopulation of CD45+/CD34+ cells was seen at 20 days posttransplantation. As it happened in the previous experiment, analyses made soon after the transplantation (day 20 posttransplantation) showed that the CD45+ repopulation of mice transplanted with the IL-3/IL-6/SCF ex vivo–expanded samples was clearly below the corresponding values found in the control group. Significantly, this was also the case in mice transplanted with samples, which had been incubated with IL-11/SCF/FL. As shown in Fig 4, recipients transplanted with either the fresh or the ex vivo–expanded grafts showed a high and stable repopulation of CD45+ cells in the long-term posttransplantation. Regarding the repopulation of CD45+/CD34+ cells in mice transplanted with the ex vivo–expanded populations, a particular delayed engraftment was apparent in the IL-11/SCF/FL group.

Kinetics of engraftment of individual NOD/SCID mice transplanted with fresh and two different types of ex vivo– expanded CD34+ cells. The figure represents the individual kinetics of engraftment of NOD/SCID mice transplanted with fresh CD34+ cells (105 cells/mouse; closed symbols) or with the ex vivo–expanded product generated after a 6-day incubation of 105 fresh CD34+ cells in the presence of IL-3/IL-6/SCF (○) and IL-11/SCF/FLT3L (▵).

Kinetics of engraftment of individual NOD/SCID mice transplanted with fresh and two different types of ex vivo– expanded CD34+ cells. The figure represents the individual kinetics of engraftment of NOD/SCID mice transplanted with fresh CD34+ cells (105 cells/mouse; closed symbols) or with the ex vivo–expanded product generated after a 6-day incubation of 105 fresh CD34+ cells in the presence of IL-3/IL-6/SCF (○) and IL-11/SCF/FLT3L (▵).

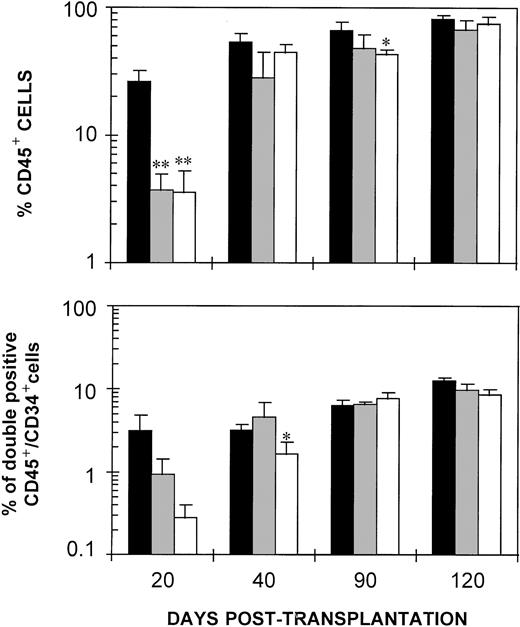

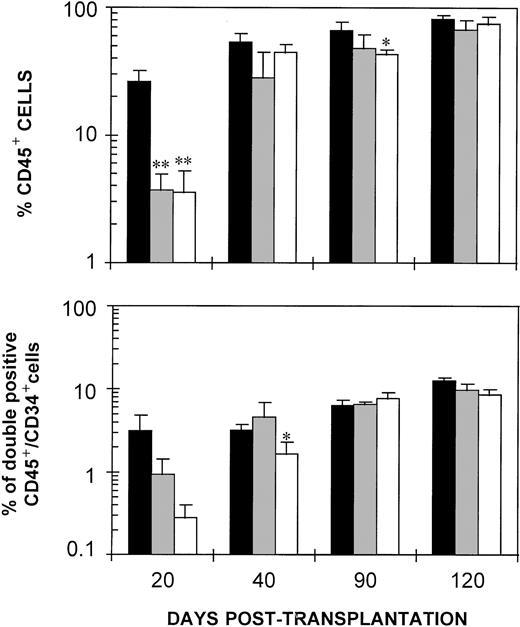

Differences between the engraftment of the three groups of NOD/SCID mice is best seen in Fig 5, which represents the mean values of CD45+ and CD45+/CD34+ cells from day 20 to day 120 posttransplantation. Marked and highly significant reductions (P < .005) in the repopulation of CD45+ cells were observed at day 20 posttransplantation in recipients transplanted with both types of in vitro incubated samples, when compared with recipients of fresh CB. Differences were maintained when the myeloid CD45+/CD33+ cells were analyzed (not shown). In contrast to these data, only minor differences between the fresh and the ex vivo–expanded groups were seen at later stages posttransplantation. When CD45+/CD34+ values were considered, a trend of delayed engraftment of mice transplanted with the ex vivo–expanded samples was also observed, although statistical differences with the control group were only obtained in mice transplanted with the IL-11/SCF/FL-stimulated CB and sampled at 40 days posttransplantation.

Delayed engraftment of NOD/SCID mice transplanted with fresh and ex vivo–expanded CD34+ cells. The figure represents the mean values of CD45+ and double-positive CD45+/CD34+ cells in the femoral BM of NOD/SCID mice shown in Fig 4, which were transplanted with fresh (▪) and with cells incubated in the presence of IL-3/IL-6/SCF (▩) and IL-11/SCF/FL (□). For further details, see legend to Fig 4.

Delayed engraftment of NOD/SCID mice transplanted with fresh and ex vivo–expanded CD34+ cells. The figure represents the mean values of CD45+ and double-positive CD45+/CD34+ cells in the femoral BM of NOD/SCID mice shown in Fig 4, which were transplanted with fresh (▪) and with cells incubated in the presence of IL-3/IL-6/SCF (▩) and IL-11/SCF/FL (□). For further details, see legend to Fig 4.

Long-term differentiation ability of fresh and ex vivo–expanded CD34+ CB cells.

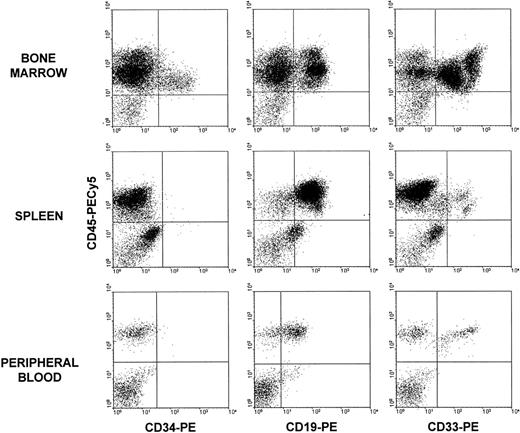

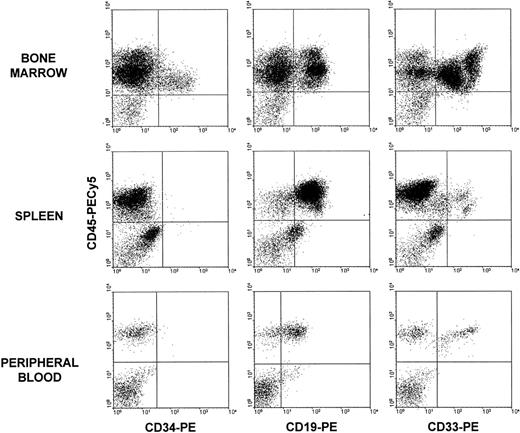

The multilineage differentiation capacity of fresh CD34+and 6-day ex vivo–expanded samples was investigated at 120 days posttransplantation. Thymus was routinely reconstituted by less than 1% of CD45+ cells and therefore it was not considered in this analysis. Figure 6 shows the hematopoietic differentiation pattern in the BM, spleen, and peripheral blood (PB) of representative NOD/SCID mice transplanted with IL-3/IL-6/SCF ex vivo–expanded cells. As shown in Fig 6, in addition to a high expression of the CD34 marker in the BM, an evident lymphomyeloid engraftment was observed in the three tissues analyzed. Similar histograms were also obtained in all recipients transplanted with fresh and IL-11/SCF/FL cultured cells (not shown).

Multilineage repopulation ability of IL-3/IL-6/SCF ex vivo–expanded samples. BM, spleen, and PB of NOD/SCID mice were examined at 120 days posttransplantation. Histograms represent cells labeled with anti–CD45-PECy5 and anti–CD34-PE, anti–CD19-PE, or anti–CD33-PE antibodies. Quadrants were set according to isotype-matched negative control stainings.

Multilineage repopulation ability of IL-3/IL-6/SCF ex vivo–expanded samples. BM, spleen, and PB of NOD/SCID mice were examined at 120 days posttransplantation. Histograms represent cells labeled with anti–CD45-PECy5 and anti–CD34-PE, anti–CD19-PE, or anti–CD33-PE antibodies. Quadrants were set according to isotype-matched negative control stainings.

A detailed analysis of the lymphohematopoiesis of NOD/SCIDs transplanted with fresh and ex vivo–expanded samples is shown in Table 1. These data confirm the capacity of either of the ex vivo–expanded samples to repopulate NOD/SCIDs with lymphomyeloid cells. As shown, T-cell reconstitution was significantly below B-cell and myeloid repopulation in all analyzed tissues, regardless of the manipulation of the graft. It is worth mentioning that a trend of increased B-cell over myeloid reconstitution was found in the BM and spleen, but not in PB, of mice transplanted with the ex vivo–expanded samples. Also, a trend of reduced T-cell repopulation was associated with the in vitro incubation process, although no significant data were obtained in this respect.

DISCUSSION

Two main aspects in the biology of ex vivo–expanded CB cells will ultimately define the applicability of these grafts in human hematopoietic transplantation. The first one relates to the actual efficacy of the ex vivo–expanded samples for improving the short-term engraftment of recipients. The second point relates to the possibility of preserving the longevity and the multipotentiality of CB cells subjected to ex vivo expansion.

Data obtained with mouse BM cells have shown an accelerated engraftment of recipients transplanted with ex vivo–expanded samples,1-6 while also showing some limitations in the short-term functionality of these grafts.6 The experiments presented in this study aimed to confirm these observations using human CB cells. Nowadays, the human-NOD/SCID mouse model20 offers one of the best approaches for investigating the in vivo repopulating ability of human hematopoietic samples.20 In addition, the possibility of monitoring the engraftment of these animals after the transplantation of human hematopoietic samples36 allowed us to investigate for the first time the kinetics of engraftment associated with the transplantation of CB cells before and after ex vivo expansion.

In our initial experiments, CB samples were stimulated with IL-3/IL-6/SCF, a growth factor combination widely used in ex vivo expansion and retroviral-mediated gene transfer protocols.19,37-40 Consistent with earlier studies,36 41 maximum values of human repopulation were reached in about 40 days after the transplantation of fresh CB. In comparison to the kinetics of engraftment observed in these recipients, the human repopulation of mice transplanted with IL-3/IL-6/SCF–incubated CB was markedly delayed (see Figs 3 through5). Significantly, this was produced even though the cellularity and CFU-GM content of the incubated samples was highly increased (16-fold and 20-fold, respectively) with respect to the fresh samples. To determine whether the delayed repopulation was a direct consequence of the IL-3/IL-6/SCF stimulation, a different combination of growth factors was also used. However, as observed after the transplantation of IL-3/IL-6/SCF–stimulated CB, a significant delay of engraftment was also observed in recipients transplanted with IL-11/SCF/FL–incubated cells (Fig 5).

Although a relative engrafting defect, as a per CFU-GM basis, was observed in ex vivo–expanded mouse BM,6 an overall improved engraftment was associated with the transplantation of these samples. In the current experiments with human CB, the engrafting defect of the cultured cells was apparent not only in a per CFU-GM basis, but also in absolute terms when comparing the engrafting ability of the samples before and after the ex vivo expansion.

Whether the engraftment delay associated with the incubation process is related to the xenogenic transplantation model used in these assays or on the contrary, whether our results are actually predicting the behavior of the ex vivo–expanded samples in human recipients is still unclear. However, consistent with our results, recent data in myeloablated baboons have shown that the transplantation of autologous ex vivo–expanded BM also results in a delayed engraftment of recipients.42 The possibility of impairing rather than improving the engraftment of patients transplanted with in vitro–incubated samples is clearly deduced from these findings and would be considered in the design of new clinical trials related to ex vivo expansion. These experimental data also suggest that other biological properties apart from the content in hematopoietic progenitors are modulating the grafting ability of the sample. This hypothesis is consistent with the current clinical results, which have not demonstrated a significant shortening in the engraftment of patients transplanted with ex vivo–expanded grafts.8-11The extent to which the proliferative activation of the progenitors26,28 or changes in the expression of adhesion molecules,43 chemokine receptors,44 or other unknown molecules are critical for the correct seeding of the hematopoietic grafts in the recipient BM is currently unknown.

Although the experiments conducted in this study cannot discriminate the generation of small changes in the content of LTRCs, our data show that no changes in the long-term engraftment of the animals are observed as a result of the transplantation of in vitro–incubated samples (Fig 5). This observation, together with the dose-dependent engraftment shown in Fig 2, indicates that no overall changes in the long-term repopulating ability of the grafts are produced during the incubation process. The generation of relative alterations in the homing and in the size and self-renewal ability of the LTRC compartment cannot be deduced, however, from our study.

Consistent with earlier studies, a lymphomyeloid engraftment of recipients was observed both when fresh41,45 and ex vivo–expanded CB cells were transplanted.32,33 The quantitative analysis of data obtained at 120 days postengraftment showed, however, a trend of reduced myeloid and T-cell reconstitution at the expense of an increased B-cell repopulation (see Table 1). Taking into account that the T-cell repopulation of NOD/SCIDs is most probably the consequence of the in vivo amplification of inoculated T cells,46 the reduced T-cell engraftment observed in the ex vivo–expanded groups could be explained by considering that residual T cells present in the CD34+ population are being purged during the incubation of the samples; something, which could be exploited in T-cell depletion strategies. The reason why recipients of ex vivo–expanded grafts contained a reduced repopulation of myeloid over B cells in BM and spleen, but not in PB, is currently unknown and should be subject of further studies.

Taken together, our data indicate that although no changes in the long-term repopulation of NOD/SCID mice are produced after the transplantation of ex vivo–expanded CB cells, a very significant delay in the engraftment of these recipients is associated with the in vitro incubation of the samples. Our observations have direct implications in the design of new clinical protocols of ex vivo expansion and emphasize the relevance of investigating more deeply the biological insights involved in the ex vivo expansion of hematopoietic progenitors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank I. Ormán for expert assistance with the flow cytometry, S. Garcı́a for excellent technical collaboration, and J. Martı́nez for careful maintenance of the animals. We also thank Dr C. Garaulet, D. Monteagudo, and N. Somolinos and the staff of midwives from Hospital General de Móstoles for umbilical cord blood collection.

Supported by Grant No. SAF 98-0008-C04-01 from the Comisión Interministerial de Ciencia y Tecnologı́a and Fundación Ramón Areces.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to J.A. Bueren, PhD, Unidad de Biologı́a Molecular y Celular, CIEMAT, Avenida Complutense 22, 28040 Madrid, Spain; e-mail: bueren@ciemat.es.