Abstract

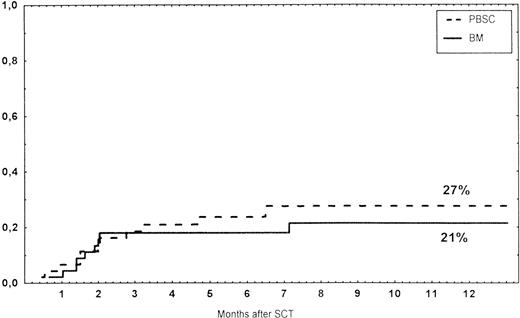

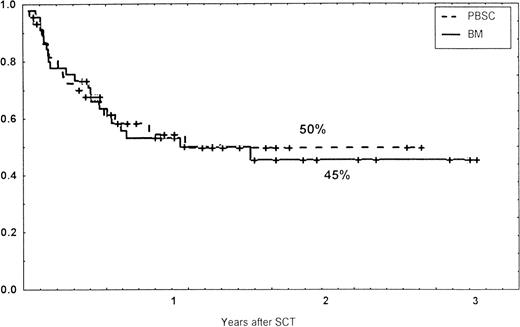

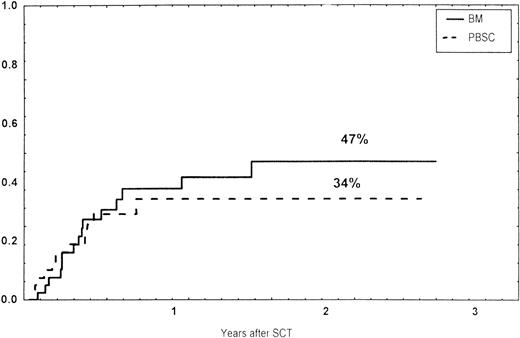

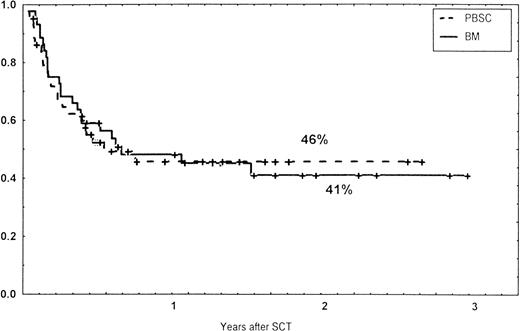

Peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) transplants from HLA-A, -B, and -DR compatible unrelated donors (n = 45) were compared with bone marrow (BM; BM group, n = 45). Eighteen patients received CD34-selected PBSC (CD34 group). The PBSCs contained more mononuclear cells, CD34+, CD3+, and CD56+cells compared with marrow (P < .001). Engraftment was achieved in all 45 patients in the BM group, in 43 of 45 (95%) in the PBSC group, and in 14 of 18 (78%) in the CD34 group (P < .01). In multivariate analysis, a short time to absolute neutrophil count (ANC) equal to 0.5 × 109/L was associated with the PBSC/CD34 groups (P < .001) and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) treatment (P = .017). A short time to platelets equal to 50 × 109/L was associated with PBSC (P = .003) and no methotrexate (P = .015). Grades II-IV acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) was 20% in the BM controls, 30% in the PBSC group, and 18% in the CD34 group (not significant [NS]). The probability of chronic GVHD was 85% in the BM group, 59% in the PBSC group, and 0% in the CD34 group (P < .01). One-year transplant-related mortality was 21% and 27% and survival was 53% and 54% in the BM and PBSC groups, respectively (NS). The 2-year relapse-free survival was 41% and 46% in the two groups, respectively.

PERIPHERAL BLOOD stem cells (PBSC) from HLA-identical siblings are increasingly used as an alternative source of hematopoietic stem cells to bone marrow (BM).1-10 In 1995, approximately 500 PBSC from HLA-identical siblings were reported to the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT); in 1996, the figure increased to more than 1,000.10 In contrast to PBSC from HLA-identical siblings, only a few patients have been reported who received PBSC from unrelated donors.11-14There have been several reasons for the reluctance to use PBSC from unrelated donors. One concern has been the ethics of using unrelated donors to mobilize PBSC, although the side-effects after the administration of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) to normal donors are tolerable after several years of follow-up.15 Another concern has been that the high T-cell content of PBSC would increase the risk of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).11,13 16 We report here the experience of PBSC from unrelated donors at four European Bone Marrow Transplant Units.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients.

The patients were eligible for transplant with PBSC if they had a disease for which marrow transplantation was indicated and after approved informed consent was obtained from the donor and recipient. In all, 63 patients received PBSC as an alternative to BM. Transplantations were performed between February 1993 and September 1998. Patients receiving PBSC were divided into two groups: those receiving unmanipulated grafts (PBSC group, n = 45) and those receiving CD34+-selected cells (CD34 group, n = 18). Among the PBSC patients, 17 were from Dresden (all CD34 selected), 16 were from Essen, 16 were from Huddinge, and 14 were from Idar-Oberstein (1 CD34 selected). Patients’ and donors’ characteristics are given in Table 1.

Informed consent.

Patients and donors were asked to participate in a study evaluating transplantation with PBSC as an alternative to BM. All patients and donors gave informed consent approved by the institutional review board at each center and also approved by the Ethics Committee at Huddinge Hospital and the Universities of Essen, Dresden, and Idar-Oberstein.

BM control group.

A control group of 45 patients who received BM from unrelated donors was selected. Each patient who received an unrelated PBSC was matched with a patient who received BM. As many variables as possible were matched between the control receiving BM and the patient receiving unmanipulated PBSC. The following prognostic factors were matched: HLA compatibility, diagnosis, disease stage, age (less than or greater than 20 years of age), GVHD prophylaxis, and transplant center. The patient transplanted with BM closest in time to each PBSC patient was selected. Among the controls, 15 were from Essen, 16 were from Huddinge, and 14 were from Idar-Oberstein. Various characteristics of the controls are given in Table 1.

Donors.

All donors were HLA-A and -B compatible with the recipient. All donor-recipient pairs were in addition DRB1 compatible, except for 2. In these 2 patients, a DRB1 subtype mismatch was present. One recipient was DRB1 1303 and the donor was 1302. The other recipient was 0408 and the donor was 0404. Both patients received PBSC in Essen. DRB3 typing was not performed in all patients. HLA-typing was serological for class I and polymerase chain reaction–single-stranded polymorphism (PCR-SSP) for class II.17 All PBSC donors received G-CSF (Rhône-Poulenc Rorer [Lyon, France] or Amgen-Roche Inc [Thousand Oaks, CA]). The G-CSF dose ranged from 9 to 12.5 μg/kg/d, administered subcutaneously once daily. G-CSF was administered for 4 days to 14, for 5 days to 42, and for 6 days to 7 donors. Among the donors producing unmanipulated PBSC, one leukapheresis was performed in 29 cases and two leukaphereses in 16. Among the donors providing CD34-selected cells, two leukaphereses were performed in 17 patients and one leukapheresis was performed in 1 patient. The donors complained of skeletal pain from G-CSF, which was relieved by paracetamol, but no other adverse effects were reported.

CD34 selection.

The apheresis products were T-cell depleted by positive selection of CD34+ cells, using immunomagnetic beads (Isolex 300 SA; Baxter, Deerfield, IL).18

Treatment regimens.

Conditioning and immunosuppression are shown in Table 2. Detailed descriptions of the myeloablative therapy, immunosuppression, and patient care at the different centers have been reported elsewhere.18-20 Most patients receiving BM or PBSC were conditioned with cyclophosphamide (CY) at 60 mg/kg/d, administered for 2 consecutive days, combined with total body irradiation (TBI) at a dose ranging from 10 to 13.5 Gy. All patients receiving CD34-selected PBSC were treated with busulfan (BU) at 16 mg/kg administered over 4 days, combined with CY at 200 mg/kg in 17 patients and at 120 mg/kg in 1 patient. As additional pretransplant immunosuppression, antithymocyte globulin (ATG) or OKT-3 was administered to all patients in the CD34 group and to some of the other patients (Table 2). Among the recipients of BM or unmanipulated PBSC, cyclosporine (CsA), combined with a short course of methotrexate, was the commonest regimen.21

Evaluation and definition.

Determinations of CD34+, CD3+, and CD56+ cells were performed on unseparated BM or leukapheresis product by flow cytometry, as previously described.14 Neutrophil engraftment was defined as occurring on the first of 2 consecutive days, with an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) greater than 0.5 × 109/L. Platelet engraftment was defined as on the first day of a platelet count greater than 50 × 109/L without platelet transfusions. Acute GVHD was graded according to standard criteria.22 Bacteremia was defined as the first positive blood culture related to a febrile episode during the first month after transplantation. Chronic GVHD was assessed in patients alive after day 90.23 Cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation was determined with PCR.24 In addition, patients in Idar-Oberstein and Essen were followed weekly by the pp 65 antigen in blood leukocytes. Transplant-related mortality (TRM) was defined as death with no relapse. Relapse was diagnosed on BM specimens taken at regular intervals and when clinically indicated.

Statistics.

Analysis was performed on October 9, 1998, with a median follow-up of 12 months (range, 1 to 37 months). The Mann-Whitney U-test was used to compare cell yield, time to engraftment, transfusions, and hospitalization. The probability of GVHD, TRM, relapse, leukemia-free survival (LFS), and survival were compared using the method of Kaplan-Meyer with a log-rank test (Mantel-Haenszel).25Cox’s regression model was used for multivariate analysis.26 Factors with P = .1 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. The following factors were analyzed: methotrexate, cell dose, CD34 dose, CD3 dose, G-CSF posttransplant, BM group, PBSC group, CD34 group, age, disease, and disease stage. For TRM, relapse, and survival, GVHD was also included. Only patients surviving more than 30 days were included in the analysis of acute GVHD. A minimum of 90 days of follow-up was the criterion for chronic GVHD.

RESULTS

Cell yield in grafts.

Nucleated cells (NC), CD34+, CD3+, and CD56+ cells were significantly higher in the PBSC leukapheresis product than in the BM control grafts (Table 3, P < .001). The CD3+ and CD56+ cell contents in PBSC were more than 10-fold higher than in BM. The CD34 cell-selected grafts contained the same number of CD34+ cells as the BM grafts. The contents of NC, CD3+, and CD56+ cells were significantly lower in the CD34 group than in the other two groups. Patients in the CD34 group received a median of 1.8 × 105 CD3+ cells/kg.

Engraftment, transfusions, and hospitalization.

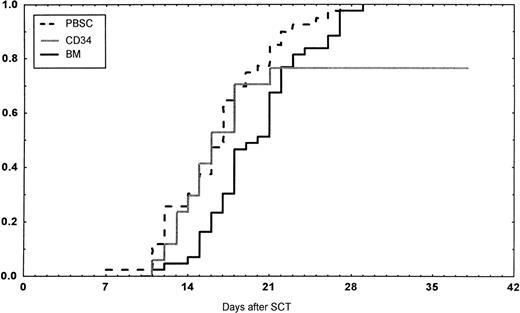

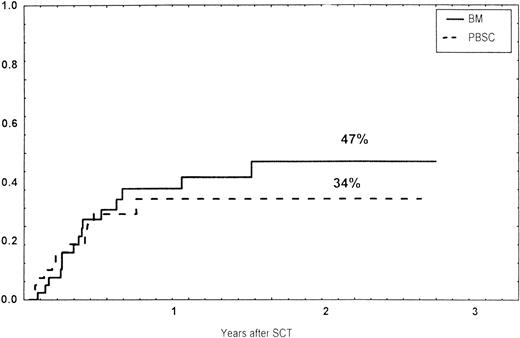

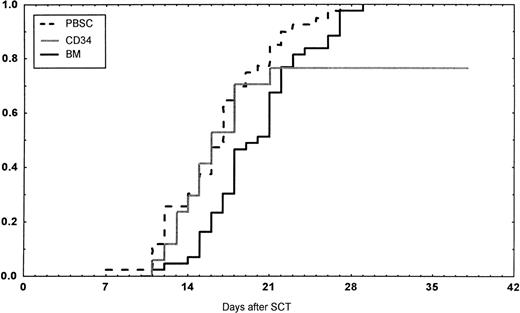

Engraftment (ANC >0.5 × 109/L) occurred in all patients in the BM group, in 43 of 45 (95%) in the PBSC group, and in 14 of 18 (78%) in the CD34 group (P < .01 v BM). However, one later graft failure occurred in the BM controls. Time to ANC greater than 0.5 × 109/L was significantly faster in the PBSC than in the BM group (Table 4,P < .001, Fig 1). Time to reach a platelet count greater than 50 × 109/L, without platelet transfusions, also was longer in the patients receiving BM than in the other two groups (P < .01). The CD34 group required fewer platelet transfusions than the BM group (P = .014). No other difference in the number of transfusions was detected between the three groups. The median time of discharge from hospital was on day 38 after transplantations in all groups.

Days to and ANC recovery to greater than 0.5 × 109/L after stem cell transplantation (SCT) with unmanipulated PBSC, BM, or CD34-selected peripheral blood stem cells (CD34). PBSC group versus BM group, P < .001. BM versus CD34 group, P = .08.

Days to and ANC recovery to greater than 0.5 × 109/L after stem cell transplantation (SCT) with unmanipulated PBSC, BM, or CD34-selected peripheral blood stem cells (CD34). PBSC group versus BM group, P < .001. BM versus CD34 group, P = .08.

In the univariate analysis, the following factors were associated with a faster ANC greater than 0.5 × 109/L: cell dose (P = .005), CD34 dose (P = .02), G-CSF posttransplant (P = .016), PBSC or CD34 group versus BM group (P < .001), and PBSC group versus others (P = .005). In the multivariate analysis, PBSC and CD34 groups versus BM group and G-CSF treatment were associated with a shorter time to ANC equal to 0.5 × 109/L (Table 5). Short time to a platelet count equal to 50 × 109/L was associated with PBSC and CD34 group versus BM group (P = .005) and PBSC group versus the other two groups (P = .02) in univariate analysis. In the multivariate analysis, the PBSC group and no methotrexate were significant (Table 5).

Infections.

Bacteremia occurred during the first 30 days in 49% of the patients receiving BM, in 38% in the PBSC group, and in 11% of those receiving CD34-enriched cells. In the BM group, 18 patients had a positive coagulase-negative staphylococcal infection, compared with 10 in the PBSC group. Bacteremia caused by α-streptococci, occurred in 3 and 2 patients in the two groups, respectively. Other types of septicemia were seen in 1 patient in the BM group, in 5 in the PBSC group, and in 2 in the CD34 group. A positive CMV PCR was found in 13 patients in the BM group, in 16 in the PBSC group, and in 4 in the CD34 group. CMV interstitial pneumonitis occurred in 1 each of the first two groups and in 2 in the CD34 group. In the latter group, 2 also had had CMV hepatitis.

One patient each in the three groups had Aspergillus infection. Two patients in the PBSC group had invasive Candida infections.

Acute and chronic GVHD.

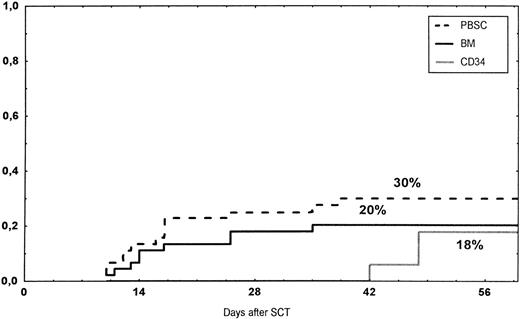

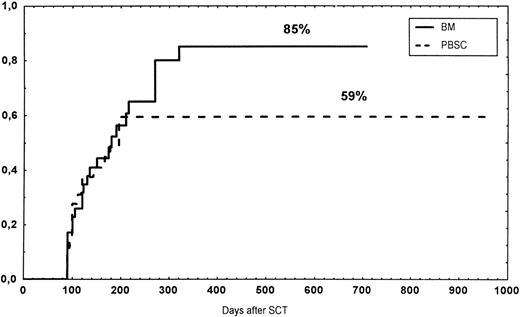

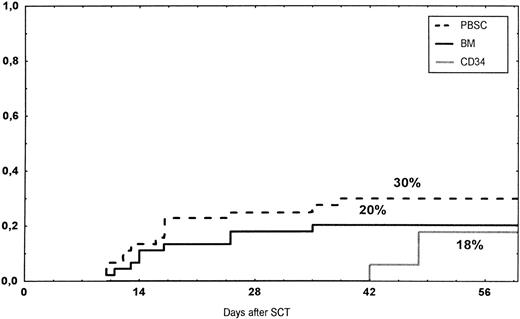

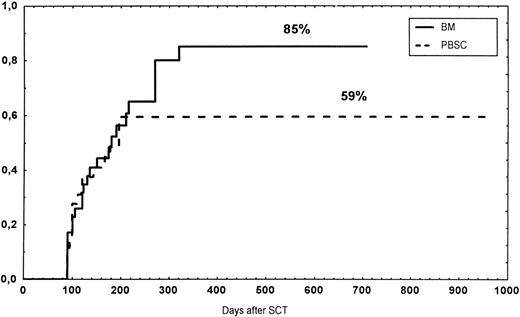

The incidence and grading of acute GVHD in the various groups are shown in Table 4. The cumulative incidence of acute GVHD grades II-IV did not differ significantly between the three groups (Fig 2). The cumulative incidences in grades III-IV acute GVHD were 16% in the BM group, 14% in the PBSC group, and 6% in the CD34 group. In the CD34 grafts, the number of CD3+ cells given to patients with grades 0-I acute GVHD was a median of 1.8 × 105/kg (range, 0.2 to 3.9 × 105/kg) versus 1.8 × 105/kg (range, 0.9 to 3.2 × 105/kg) in those with grades II-IV. In multivariate analysis, acute GVHD grades II-IV was associated with OKT3 treatment, age greater than the median (30 years), and donor CMV seropositivity (Table 5). The number of patients with chronic GVHD is also shown in Table 4. No patient in the CD34 group developed chronic GVHD, which was significant versus the BM group (P < .001) and the PBSC group (P = .004). The 1-year cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD in the BM group was 77%, compared with 65% in the PBSC group (Fig 3).

Time to and cumulative incidence of grades II-IV acute GVHD after stem cell transplantation (SCT) of unrelated PBSC (30%), BM (20%), or CD34 selected PBSC (CD34; 18%).

Time to and cumulative incidence of grades II-IV acute GVHD after stem cell transplantation (SCT) of unrelated PBSC (30%), BM (20%), or CD34 selected PBSC (CD34; 18%).

Time to and cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD in recipients of BM (85%) or PBSC (59%; P = .4).

Time to and cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD in recipients of BM (85%) or PBSC (59%; P = .4).

Causes of death, relapse, and survival.

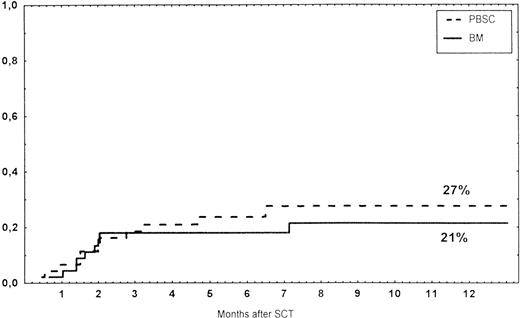

Causes of death are shown in Table 6. Overall TRM and patient survival rates did not differ significantly between the three groups (Figs 4 and5). The 1-year survival rates were 53% in the BM group and 54% in the PBSC group. At 2 years, the actuarial survival rates were 45% in the BM group versus 50% in the PBSC group. In patients with hematological malignancies, the probability of relapse did not differ significantly between the two groups (Fig 6). At 1 year, the probabilities of relapse were 38% in the BM controls and 34% in the PBSC patients. For early disease, relapse probability was 14% in both groups. In high-risk patients, the corresponding figures for the BM group was 74%, compared with 53% for the PBSC group (not significant [NS]). Relapse-free survival rates did not differ significantly between the two groups (Fig 7). One year after transplantation, relapse-free survival rates were 48% in the BM controls and 46% in the PBSC group. In patients with low-risk disease, LFS at 1 year was 63% in the PBSC group and 70% in the BM group. In patients with high-risk disease, the corresponding figures were 33% and 31% in the two groups, respectively.

Survival rates of patients grafted with BM or unmanipulated PBSC from unrelated donors.

Survival rates of patients grafted with BM or unmanipulated PBSC from unrelated donors.

Time to and cumulative incidence of relapse in patients with hematological malignancies and those receiving BM or unmanipulated PBSC from unrelated donors.

Time to and cumulative incidence of relapse in patients with hematological malignancies and those receiving BM or unmanipulated PBSC from unrelated donors.

Relapse-free survival (RFS) of patients grafted with unmanipulated PBSC or BM from unrelated donors.

Relapse-free survival (RFS) of patients grafted with unmanipulated PBSC or BM from unrelated donors.

At 1 year, the CD34 group had a TRM of 60%, a survival rate of 31%, a relapse rate of 48%, and an LFS of 25%. The Kaplan-Meier curves did not differ significantly from the other two groups.

Multivariate analysis for TRM, relapse, and survival.

For TRM, the following risk-factors were significant in multivariate analysis, no methotrexate, and acute GVHD grades II-IV (Table 5). Relapse was associated with high risk disease and absence of chronic GVHD in multivariate analysis. The following factors were significant in the multivariate analysis of survival: low-risk disease, chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) versus acute leukemia, age less than 35 years, and acute GVHD grades 0-I. For LFS, low-risk disease and chronic GVHD were significant in the multivariate analysis.

DISCUSSION

This study shows that PBSC from unrelated HLA-A, -B, -DR compatible donors can be safely administered as an alternative to BM. The PBSC group had a significantly faster engraftment of ANC and platelets than that in the BM controls. This is in agreement with several studies comparing PBSC with BM from HLA-identical siblings and is also in line with the preliminary experience using PBSC from unrelated donors.4-6,13 The vast majority of patients in the BM and PBSC groups were treated with GVHD prophylaxis, including methotrexate, which prolongs engraftment more than cyclosporine used alone.27 G-CSF posttransplant, which enhances engraftment, was also administered to similar percentages of patients in the BM and PBSC groups. Patients in the BM group received G-CSF for a longer time (Table 2). However, a randomized trial in recipients of unrelated BM showed no difference in time to ANC, if G-CSF was started at 0, 5, or 10 days after transplantation.28 The reason for the faster engraftment in the PBSC patient than in those receiving BM is probably because of the higher graft content of CD34+ cells. For engraftment of ANC and platelets, the CD34 content of the graft appears to be of utmost importance.14,29 Therefore, it may seem surprising that the patients receiving CD34-selected cells had as fast an engraftment as those receiving PBSC, despite fewer CD34 cells in the graft (Tables 4 and 5). The reason for this is probably that only one third of the patients receiving CD34-selected cells received methotrexate posttransplant (Table 2). In a randomized trial by the EBMT, there was no difference in time to ANC and platelet engraftment in HLA-identical siblings receiving PBSC as compared with BM.10 This is probably because the CD34 contents were the same in the two groups. However, despite the faster engraftment in the PBSC and CD34 groups, time to discharge from hospital did not differ from the BM group (Table 4). The reason for this may be that there are several other problems, such as infections, nutrition, and GVHD, that must be dealt with before the patients can be discharged. Moreover, PBSC from unrelated donors is a new procedure and, because of lack of experience, at least in the beginning, discharge may have been delayed in some patients.

Graft failure was more common in the CD34 group than in recipients of unmanipulated grafts in this study (P < .01). This is in accordance with the experience that T-cell depletion increases the risk of graft failure.30 31

An important finding is that there was no difference in acute GVHD between patients receiving PBSC compared with those receiving BM, despite the 10-fold higher content of T cells (Table3).13,16 In HLA-identical siblings, we found no correlation between T-cell dose in T-replete BM grafts and the probability of moderate-to-severe acute GVHD, which is in agreement with this.32 Overall, roughly one third of the patients receiving unrelated PBSC or BM developed moderate-to-severe acute GVHD, which is less than that reported by others using unrelated marrow.33,34 One reason for this may be that, in addition to methotrexate and cyclosporine, some patients received ATG, which may reduce the incidence of acute GVHD.35 However, an increased incidence of GVHD was seen in the OKT3 group. The low incidence of GVHD in the group receiving CD34-enriched cells is expected because of the effective CD3 depletion in this group (Table 3). If T-cell depletion of the graft is performed, the T-cell dose seems important for the development of GVHD.36 In HLA-identical siblings, a threshold dose for acute GVHD is estimated to be approximately 5 × 105 CD3+ cells/kg. All of the patients receiving CD34-enriched PBSC received a lower dose. However, the CD3+ dose was not important for acute GVHD in this limited material. Moreover, the patients receiving CD34-selected grafts also received ATG.

So far, no patient in the CD34 group has developed chronic GVHD. This may be due to the close correlation between acute GVHD and chronic GVHD.37,38 The probability of chronic GVHD was the same in the PBSC and the BM groups. It was thought that PBSC, because of its high cell content, would increase the risk of chronic GVHD. For instance, treatment with donor buffy coat cells in association with transplantation increases the risk of chronic GVHD.37 Two studies found an increased risk of chronic GVHD in HLA-identical siblings receiving PBSC compared with BM.39,40 This was not seen in our study of unrelated PBSC versus BM. The reason for this may be the high risk of chronic GVHD even with unrelated BM, which is greater than 80%, compared with approximately 40% in HLA-identical siblings.33,34,37 38

With regards to survival, relapse, and relapse-free survival, there was no difference between outcome in patients receiving PBSC compared with the BM controls (Figs 5, 6, and 7). This is in agreement with the experience of PBSC versus BM in HLA-identical siblings.6,10It was hoped that the higher T-cell content in PBSC would have a stronger antileukemic effect than that seen with BM. However, the antileukemic effect may be induced by activated T cells during acute and chronic GVHD rather than inactive T cells of a T-replete graft.41-43 Our follow-up of the patients was rather short, and the survival and relapse data must therefore be viewed with caution. However, the outcome is in line with the experience in HLA-identical siblings.6,10 Because the number of patients receiving CD34-selected cells was small, they were not matched with the other two groups, and the observation time was short, care should be taken regarding the interpretation of the outcome. There was a trend for more high-risk patients in the CD34 group, compared with the other two groups (Table 1). The risk-factors for survival and LFS in this study (disease-stage, age, acute leukemia versus CML, acute GVHD, and absence of chronic GVHD) are in accordance with previous publications.33,34,41 43

Despite the limitations of the study, we conclude that transplantation of PBSC from unrelated donors is a safe procedure and results in a faster engraftment than with BM. It was also reported previously that PBSC resulted in a better immune reconstitution than with BM.44 Apart from these advantages for the recipient, there may be several advantages for the donor than with donation of BM. There is no need for hospitalization, general anesthesia, and blood transfusions. Instead, the donors are subjected to the risks of treatment with G-CSF, which include skeletal pain and thrombocytopenia after leukapheresis. A rare complication in one donor was splenic rupture.45 Thrombosis may be a risk, and 2 patients developed vascular side effects after donation of PBSC: 1 cerebrovascular accident and 1 myocardial infarction.46 In the long term, there will probably be little risk for the donor. Although unlikely, the question has been raised as to whether G-CSF mobilization of PBSC may increase the risk of leukemia. It has also been discussed whether repeated treatment of G-CSF can cause marrow exhaustion and pancytopenia. Because of these concerns, it is important to observe PBSC donors for several years after the donations. In the Nordic countries, PBSC donors will be observed and registered at 3-year intervals and compared with BM donors and registered to the national survival and cancer registries. However, a large number of PBSC donors and a long follow-up will be required before these issues can be settled.

It is expected that the use of PBSC from unrelated donors will increase in the same way as PBSC from HLA-identical siblings because of its benefits for the recipient and the donor.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the staff at the various units for expert patient care. We thank Inger Hammarberg for excellent typing of the manuscript.

Supported by grants from the Swedish Cancer Foundation (0070-B95-09XCC), the Children’s Cancer Foundation (1995/035), the Swedish Medical Research Council (B96-16X-05971-16C), the FRF Foundation, the Tobias Foundation, and the Ellen Bachrach Foundation.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to O. Ringdén, MD, PhD, Department of Clinical Immunology, Huddinge Hospital, F79, SE-141 86 Huddinge, Sweden; e-mail: olle.ringden@immunlab.hs.sll.se.