Abstract

Tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) is the primary physiological inhibitor that regulates tissue factor-induced blood coagulation. TFPI is thought to be synthesized, in vivo, primarily by microvascular endothelial cells. Little is known about how TFPI is regulated under pathophysiological conditions. In this study, we determined mechanisms by which TFPI expression is regulated by human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMC), because these cells contribute to remodeling of the pulmonary vasculature in disease. PASMC in culture constitutively synthesize and secrete TFPI. Exposure of PASMC to phorbol myristate acetate, lipopolysaccharide, tumor necrosis factor , thrombin, interleukin-1, and transforming growth factor-β had no significant effect on expression of TFPI by PASMC. By contrast, treatment of PASMC with serum and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF)/heparin markedly upregulated the expression of TFPI activity and antigen. On Western blot analysis, a protein consistent with full-length TFPI (42 kD) was identified in the conditioned media of PASMC, and the levels of the protein were much higher in the conditioned media of serum and bFGF/heparin-treated cells. Northern blot analysis showed that PASMC constitutively express TFPI mRNA, and treatment of cells with serum and bFGF/heparin had a minimal effect on the steady-state levels of TFPI mRNA. Nuclear run-on analysis did not show a significant increase in the transcriptional rate of TFPI gene in PASMC treated with serum or bFGF/heparin. Cycloheximide, but not actinomycin-D, treatment inhibited the serum and bFGF/heparin-induced increase in TFPI activity in PASMC. In conclusion, our data demonstrate that PASMC constitutively synthesize and secrete TFPI and serum or bFGF upregulate its expression, suggesting that growth factors that can stimulate the vessel wall in vivo might locally regulate TFPI expression. Our study also suggests that control of TFPI expression by serum or bFGF occurs via translational rather than transcriptional regulation.

THE PULMONARY ARTERIAL vasculature responds to various insults with a characteristic pattern of remodelling that includes hyperplasia of smooth muscle cells and an increase in connective tissue in the medial layer of the vessel wall.1 Although the pathogenetic mechanism(s) of medial hypertrophy is not fully characterized, the process appears to involve functional derangements of endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMC).2 Thrombosis plays an important role in pulmonary vascular injury.3 The tissue factor (TF) pathway of coagulation plays a primary role in hemostasis and the pathophysiology of many diseases, including coronary thrombosis, sepsis, and cancer.4-8 In particular, TF-induced procoagulant activity has been implicated in fibrin deposition and fibrosis associated with lung injury.9Furthermore, factor Xa and thrombin, the intermediary products of the TF-pathway of coagulation, promote vascular smooth cell proliferation10 11 and may thus play a role in the development of intimal hyperplasia.

Tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI), a multivalent protease inhibitor with three Kunitz-type domains, is the primary inhibitor of TF-mediated coagulation.12,13 TFPI directly inhibits factor Xa and blocks the procoagulant activity of the TF/VIIa complex by forming a quaternary TF/VIIa/Xa/TFPI complex.13 Under physiological conditions, TFPI is primarily synthesized by the microvascular endothelium and in relatively smaller amounts by megakaryocytes and macrophages.14-17 Human umbilical vein vascular smooth muscle cells and lung fibroblasts were found to synthesize only small amounts of TFPI.14 Little is currently known about how the expression of TFPI is regulated within the pulmonary vasculature.

In the present study, we sought to determine how the expression of TFPI is regulated in vascular smooth muscle cells in response to various agents implicated in the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hyperplasia. The data demonstrate that PASMC constitutively express TFPI and that serum and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) upregulate the expression of TFPI activity. Our data also provide evidence, for the first time, that the control of TFPI expression in PASMC occurs via translational rather than transcriptional regulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

The cytokines used in the present study (bFGF, transforming growth factor-β [TGF-β], tumor necrosis factor α [TNFα], and interleukin-1β [IL-1β]) were human recombinant proteins from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Escherichia coli serotype O111:B4) were obtained from Sigma Chemical and Co (St Louis, MO). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was from GIBCO-BRL (Grand Island, NY). TRI Reagent was obtained from Molecular Research Center Inc (Cincinnati, OH). [γ32P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol) and [α32P]dCTP (3,000 Ci/mmol) were from Dupont NEN (Boston, MA). Molecular biology grade chemicals were obtained from either Boehringer Mannheim (Indianapolis, IN) or US Biochemicals (Cleveland, OH). Other chemicals were obtained from Sigma and Fisher (Fair Lawn, NJ).

Purified proteins.

Recombinant factor VIIa and full-length TFPI were gifts from Novo-Nordisk (Gentofte, Denmark). Human plasma factor X18and factor Xa19 were purified as described earlier or purchased from Enzyme Research Laboratories Inc (Southbend, IN). Thrombin was purchased from Enzyme Research Laboratories Inc.

Cell culture.

Primary cultures of PASMC and coronary artery smooth muscle cells (CASMC) were obtained from Clonetics and cultured to confluency in SmGM-2 growth medium (Clonetics, San Diego, CA) at 37°C under 5% CO2. The cells were subcultured by first detaching the cells with trypsin solution and replating them in 24-well culture plates (for measurement of TFPI activity and antigen) or in T-75 flasks (for isolation of nuclei and RNA). When cells reached 90% confluency, the growth medium was replaced with basal medium, SmBM (Clonetics), supplemented with 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and cultured for 24 hours. Cells between 5 to 10 passages were used in the experiments.

Stimulation of PASMC.

Quiescent PASMC (serum and growth factor-starved for 24 hours) in 24-well culture plate were stimulated with 1 mL of fresh basal medium containing 10% (vol/vol) FBS or bFGF (10 ng/mL) in the presence of heparin (15 U/mL) or other agonists as described in Results. At specific intervals, 50 to 100 μL of supernatant was removed from the well and stored at −20°C to measure TFPI activity and antigen levels. As controls, cells were treated with basal medium for identical lengths of time. To induce TF activity, quiescent PASMC were treated for 8 hours with agonists. At the end of 8 hours, cell supernatants were removed and the monolayers were washed twice with phosphate buffer. Cell extracts were made by lysing PASMC in 0.25 mL of 15 mmol/L octyl glucopyranoside. All treatments were performed under sterile conditions, and the monolayers were allowed to stay in a culture incubator.

Measurement TFPI activity.

TFPI activity was determined in a two-stage chromogenic assay as described earlier using purified human coagulant proteins.20 A TFPI standard curve was obtained using dilutions of 0.125% to 4% pooled human plasma. TFPI activity present in 1 mL of normal plasma was taken as 1,000 mU. To measure TFPI activity in cell lysates, the above assay was modified to contain a limited concentration of factor VIIa (1 ng/mL) and an excess of TF (10 ng/mL) to avoid the interference of cell lysate TF in the assay. In this assay, recombinant TFPI (0.25 to 4 ng/mL) was used to generate the standard curve. Normal plasma contains 100 ng/mL TFPI, which is equivalent to 1,000 mU TFPI activity. TFPI activity measured in FBS was used to correct TFPI activity measurements of the conditioned media containing serum.

Measurement of TFPI antigen.

TFPI antigen was measured in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described earlier using rabbit antihuman TFPI IgG as a capturing antibody and biotinylated rabbit antihuman TFPI IgG as a reporter antibody.20 Monospecific rabbit antihuman TFPI antiserum was obtained by immunizing a rabbit with recombinant human TFPI protein. A TFPI antigen standard curve was obtained using dilutions of 0.625% to 10% pooled human normal plasma.

Measurement of TF activity.

TF activity was measured based as the ability of cell lysates to support the activation of factor X with the addition of VIIa. Briefly, cell lysates (45 μL) were incubated with a reagent mixture (5 μL) containing factor VIIa (0.5 μg/mL), factor X (10 μg/mL), and CaCl2 (5 mmol/L) in a microplate (all concentrations were final concentrations). At the end of 15 minutes, 50 μL of Chromozym X containing 25 mmol/L EDTA was added to each well and the initial rate of color development in mOD per minute at 405 nm was measured with a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Menlo Park, CA). Purified relipidated human TF (0.0625 to 1 ng/mL) was used to construct a standard curve.

Western blot analysis.

Cell supernatant samples (100 μL) were subjected to nonreduced sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on 12% acrylamide gels and blotted onto a PVDF membrane. The blot was probed with rabbit antihuman TFPI IgG (100 μg/mL) or rabbit antiserum against TFPI C-terminal peptide (100-fold dilution) (kindly provided by Dr George Broze, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, MO) and developed using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system kit (Amersham Life Sciences, Arlington Heights, IL).

RNA isolation and Northern blot analysis.

Total RNA was prepared from cells cultured in T-75 flasks by the acid phenol method using TRI reagent according to the manufacturer’s technical bulletin (Molecular Research Center, Inc, Cincinnati, OH). Ten micrograms of total RNA was size-fractionated by gel electrophoresis in 1% agarose/6% formaldehyde gels and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane by a capillary blot method. Northern blots were hybridized using a 32P-labeled TFPI cDNA probe described earlier.21 For quantitative purposes, the blot was also exposed to a phosphor screen and the exposed screen was analyzed in a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA) using ImageQuant software.

Nuclear run-on assay.

Nuclei from 4 to 6 × 106 PASMC were harvested and run-on assays were performed with [α-32P]UTP-labeled RNA as described previously.22

RESULTS

Effect of various agonists on TFPI and TF expression by PASMC.

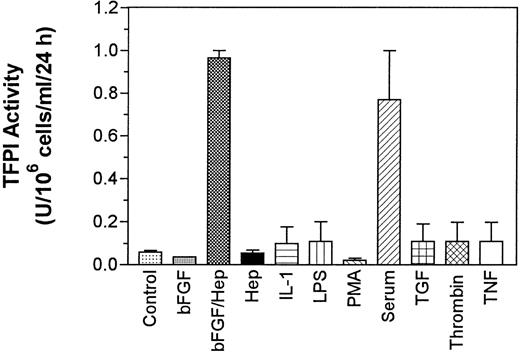

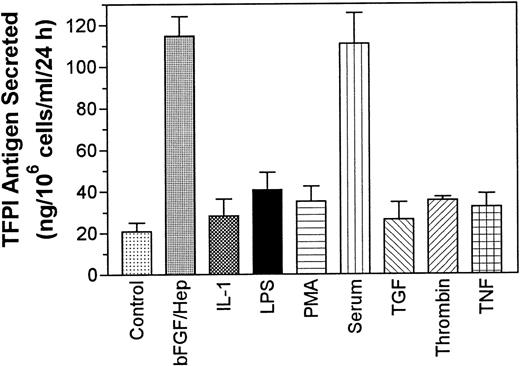

Quiescent monolayers of PASMC in 24-well culture plates were treated for 24 hours with basal medium alone (control) or the basal medium supplemented with various agonists and TFPI activity in the conditioned media and cell lysate was measured. The data obtained with the conditioned media showed that quiescent PASMC expressed low levels of TFPI (60 mU/106 cells/mL/24 h) constitutively and the treatment of cells with LPS, TNF-α, thrombin, TGF-β, and IL-1β slightly increased (<2-fold) the expression of TFPI activity. However, the levels of TFPI secretion obtained with these treatments was not statistically significantly higher than the level of TFPI secretion observed with the cells treated with the control basal medium (P values are in the range of .4 to .6, n = 3). By contrast, treatment of PASMC with either serum (10% vol/vol) or bFGF/heparin markedly enhanced (by 12- to 15-fold) the expression of TFPI activity (Fig 1). The treatment of PASMC with either bFGF or heparin alone had no effect on the expression of TFPI activity. Smooth muscle cells from another vascular site (CASMC) also responded to bFGF/heparin and serum treatments. Treatment of CASMC with bFGF/heparin or serum increased the secretion of TFPI activity by fourfold and fivefold, respectively. The actual levels of TFPI secreted from CASMC are as follows: control (no treatment), 32 ± 7.8 mU/106 cells/mL/24 h; bFGF/heparin treated, 121 ± 45 mU/106 cells/mL/24 h; and serum (10% vol/vol) treated, 159 ± 63 mU/106 cells/mL/24 hours (n = 3 to 6). Measurement of TFPI antigen in the conditioned media showed a fivefold to sixfold increase in TFPI antigen levels in PASMC treated with serum or bFGF/heparin over the cells treated with the basal medium alone (Fig 2). A small increase in TFPI antigen levels observed in PASMC treated with other agonists was not statistically significant over TFPI antigen levels secreted in untreated cells (P values varied between .15 and .65, n = 3).

Effect of various pathophysiological agents on the expression of TFPI activity by PASMC. Quiescent PASMC monolayers were treated for 24 hours with one of the following agents: PMA (10 ng/mL), serum (10% vol/vol), LPS (1 μg/mL), TNF- (10 ng/mL), thrombin (5 U/mL; 1.5 μg/mL), TGF-β (10 ng/mL), IL-1β (10 ng/mL), bFGF (10 ng/mL), and heparin (15 U/mL). In control, no agonist was added. The conditioned media, removed at the end of 24 hours of treatment, was assayed for TFPI activity. The data shown are the mean of three experiments performed in duplicate ± SD.

Effect of various pathophysiological agents on the expression of TFPI activity by PASMC. Quiescent PASMC monolayers were treated for 24 hours with one of the following agents: PMA (10 ng/mL), serum (10% vol/vol), LPS (1 μg/mL), TNF- (10 ng/mL), thrombin (5 U/mL; 1.5 μg/mL), TGF-β (10 ng/mL), IL-1β (10 ng/mL), bFGF (10 ng/mL), and heparin (15 U/mL). In control, no agonist was added. The conditioned media, removed at the end of 24 hours of treatment, was assayed for TFPI activity. The data shown are the mean of three experiments performed in duplicate ± SD.

Secretion of TFPI antigen by PASMC treated with various pathophysiological agents. PASMC monolayers were treated as described in Fig 1 and TFPI antigen levels in the conditioned media were determined as described in Materials and Methods (n = 3).

Secretion of TFPI antigen by PASMC treated with various pathophysiological agents. PASMC monolayers were treated as described in Fig 1 and TFPI antigen levels in the conditioned media were determined as described in Materials and Methods (n = 3).

The measurement of TFPI activity in cell lysates showed that a small fraction of TFPI activity was associated with cells (∼5 to 10 mU/106 cells/mL/24 h). Treatment of the cells with agonists, including serum and bFGF/heparin, did not increase TFPI activity in cell lysates.

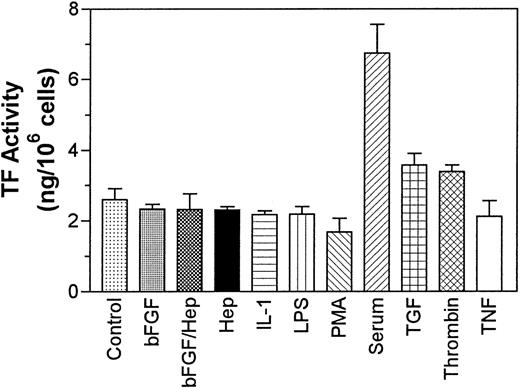

In addition to TFPI, we also measured the effect of various agonists on the expression of TF activity by PASMC. PASMC constitutively expressed substantial amounts of TF and serum treatment enhanced the expression of TF activity by 2.5-fold, whereas bFGF/heparin had no effect on the expression of TF activity. Thrombin and TGF-β treatments increased TF activity minimally (P = .095 for thrombin and P = .13 for TGF-β), and LPS, IL-1β, and TNF-α had no effect on the expression of TF activity by these cells (Fig 3).

Effect of various agonists on expression of TF activity by PASMC. Quiescent PASMC monolayers were treated for with various agonists as described in Fig 1 for 8 hours and the cell lysates were harvested to measure TF activity. In control, no agonist was added to cells. The data shown are the mean of three experiments performed in duplicate ± SD.

Effect of various agonists on expression of TF activity by PASMC. Quiescent PASMC monolayers were treated for with various agonists as described in Fig 1 for 8 hours and the cell lysates were harvested to measure TF activity. In control, no agonist was added to cells. The data shown are the mean of three experiments performed in duplicate ± SD.

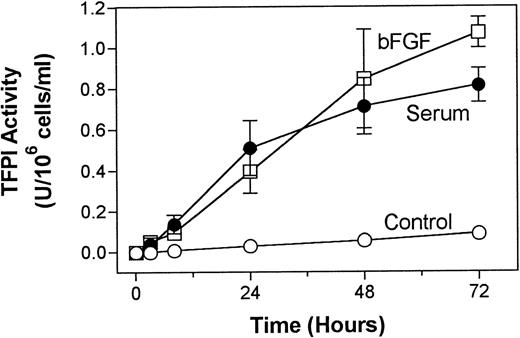

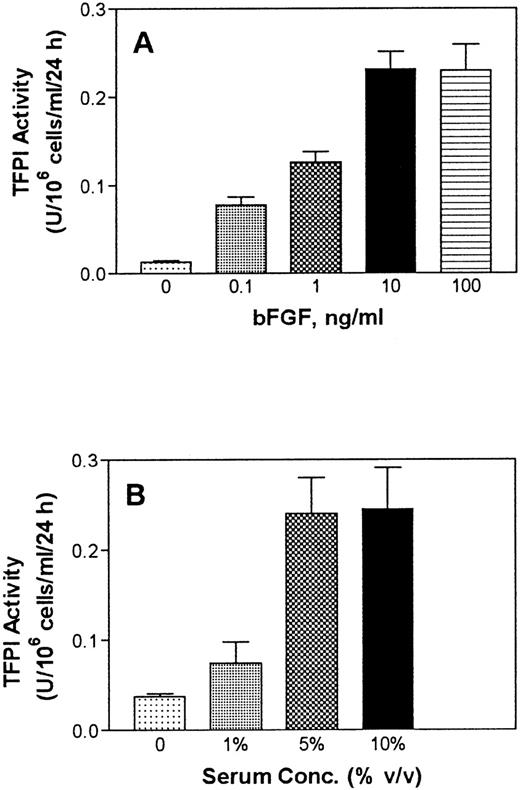

The effect of serum and bFGF/heparin on TFPI expression was found to be both time- and dose-dependent. TFPI secretion from PASMC in culture was increased, although not linearly but steadily, over a 72-hour experimental time period (Fig 4). Treatment of PASMC with varying concentrations of bFGF in the presence of a fixed concentration of heparin showed a dose-dependent increase in TFPI secretion. A concentration of 10 ng/mL bFGF enhanced TFPI expression maximally (Fig 5A). Similarly, serum treatment of PASMC enhanced the expression of TFPI in a dose-dependent manner, and the expression of TFPI was maximal in cells treated with 5% (vol/vol) serum (Fig 5B).

Time course of serum- and bFGF-enhanced TFPI secretion in PASMC. Quiescent PASMC monolayers were treated with basal medium alone (control) or with the basal medium containing serum (10% vol/vol) or bFGF/heparin (10 ng/15 U/mL). At various time points, 50 μL of aliquots was removed from the supernatant conditioned media and stored at −80°C until assayed for TFPI activity. The data shown are the mean of three experiments performed in duplicate ± SD.

Time course of serum- and bFGF-enhanced TFPI secretion in PASMC. Quiescent PASMC monolayers were treated with basal medium alone (control) or with the basal medium containing serum (10% vol/vol) or bFGF/heparin (10 ng/15 U/mL). At various time points, 50 μL of aliquots was removed from the supernatant conditioned media and stored at −80°C until assayed for TFPI activity. The data shown are the mean of three experiments performed in duplicate ± SD.

Serum and bFGF dose-dependent secretion of TFPI by PASMC. (A) Monolayers of quiescent PASMC were treated with basal medium alone (0) or with the basal medium containing varying concentrations of bFGF in the presence of a fixed concentration of heparin (15 U/mL). (B) PASMC were treated with basal medium alone (0) or varying concentrations (vol/vol) of serum. At the end of 48 hours, the conditioned media was removed and assayed for TFPI activity (n =3).

Serum and bFGF dose-dependent secretion of TFPI by PASMC. (A) Monolayers of quiescent PASMC were treated with basal medium alone (0) or with the basal medium containing varying concentrations of bFGF in the presence of a fixed concentration of heparin (15 U/mL). (B) PASMC were treated with basal medium alone (0) or varying concentrations (vol/vol) of serum. At the end of 48 hours, the conditioned media was removed and assayed for TFPI activity (n =3).

Western blot analysis of TFPI expressed by PASMC.

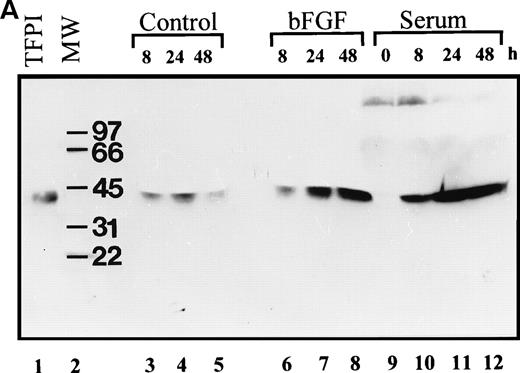

Western blot analysis of conditioned media from the cells with anti-TFPI IgG showed a protein of similar size (42 kD) to that of a full-length rTFPI isolated from transfected BHK cells (Fig 6A), suggesting that the TFPI secreted in PASMC was the full-length form. Furthermore, a mixture of rTFPI and the media containing TFPI was migrated as a single band on SDS-PAGE. Moreover, immunoblot analysis of the conditioned media from both bFGF and serum-treated cells with a TFPI C-terminal domain specific antibody showed that the PASMC-secreted TFPI contained C-terminal domain (Fig6B). Consistent with the measurements of TFPI activity and antigen, Western blot analysis also showed that quiescent PASMC constitutively express low levels of TFPI, and bFGF/heparin or serum markedly enhanced the expression of TFPI (Fig 6A).

Western blot analysis of PASMC-secreted TFPI. (A) Quiescent PASMC were treated with basal medium alone (lanes 3 through 5) or the basal medium containing bFGF/heparin (10 ng/15 U/mL; lanes 6 through 8) or serum (10% vol/vol; lanes 10 through 12) for 8 (lanes 3, 6, and 10), 24 (lanes 4, 7, and 11), and 48 hours (lanes 5, 7, and 12). Other lanes are as follows: lane 1, full-length recombinant TFPI from BHK cells; lane 2, molecular weight markers; and lane 9 (zero time), aliquot from the serum-containing medium that was removed immediately after its addition to the cells. The blot was probed with monospecific polyclonal anti-TFPI IgG. (B) One hundred microliters of conditioned media from cells treated for 48 hours with serum-free (control), bFGF (10 ng/mL)/heparin (15 U/mL) (bFGF), and serum (10% vol/vol)-containing media were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis. Other lanes are as follows: full-length recombinant TFPI from BHK cells, diluted either in a buffer (rTFPI) or in control serum (10% vol/vol). The blot was probed with a 100-fold diluted rabbit antiserum raised against TFPI C-terminal domain peptide. Molecular weight markers are Bio-Rad prestained markers (low range).

Western blot analysis of PASMC-secreted TFPI. (A) Quiescent PASMC were treated with basal medium alone (lanes 3 through 5) or the basal medium containing bFGF/heparin (10 ng/15 U/mL; lanes 6 through 8) or serum (10% vol/vol; lanes 10 through 12) for 8 (lanes 3, 6, and 10), 24 (lanes 4, 7, and 11), and 48 hours (lanes 5, 7, and 12). Other lanes are as follows: lane 1, full-length recombinant TFPI from BHK cells; lane 2, molecular weight markers; and lane 9 (zero time), aliquot from the serum-containing medium that was removed immediately after its addition to the cells. The blot was probed with monospecific polyclonal anti-TFPI IgG. (B) One hundred microliters of conditioned media from cells treated for 48 hours with serum-free (control), bFGF (10 ng/mL)/heparin (15 U/mL) (bFGF), and serum (10% vol/vol)-containing media were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis. Other lanes are as follows: full-length recombinant TFPI from BHK cells, diluted either in a buffer (rTFPI) or in control serum (10% vol/vol). The blot was probed with a 100-fold diluted rabbit antiserum raised against TFPI C-terminal domain peptide. Molecular weight markers are Bio-Rad prestained markers (low range).

Effect of serum and bFGF/heparin on the expression of TFPI mRNA in PASMC.

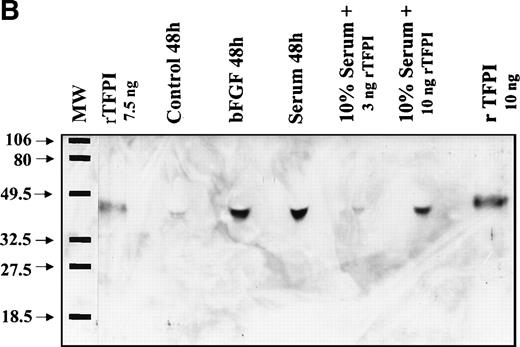

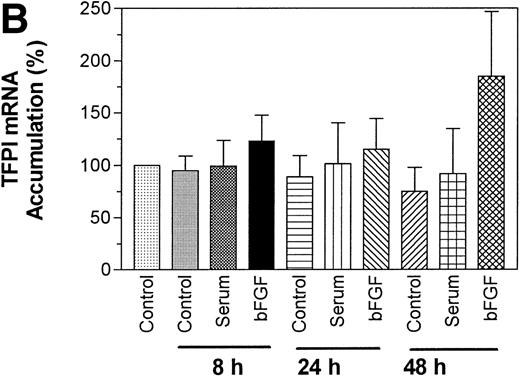

Because serum and bFGF/heparin treatments enhanced TFPI activity and antigen levels in PASMC, we next investigated the effect of these treatments on the expression of TFPI mRNA by Northern blot analysis. As shown in Fig 7, quiescent PASMC constitutively express TFPI mRNA. Treating PASMC with serum or bFGF/heparin for 8 and 24 hours did not increase the level of TFPI mRNA expression, although at these time points we observed a marked increase in the expression of TFPI activity and antigen in PASMC (see Figs 1, 2, and 4). It is interesting to note that TFPI mRNA levels were slightly but consistently higher (2-fold, P = .046, n = 4) in PASMC treated with bFGF/heparin for 48 hours. Although both 4- and 1.4-kb messages were present in PASMC, the predominant TFPI mRNA in smooth muscle cell was 4 kb (∼80%).

Effect serum and bFGF on TFPI mRNA accumulation in PASMC. Quiescent PASMC were treated with basal medium alone or the basal medium containing serum (10% vol/vol) or bFGF/heparin (10 ng/15 U/mL) for 8, 24, and 48 hours. Total RNA was isolated from the cells, 10 μg of each RNA sample was used for Northern blot analysis, and the blot was hybridized with a radiolabeled TFPI cDNA probe and exposed to x-ray film (A). Because the TFPI 1.4-kb message in these cells was about 20% of the total TFPI message and migrated as a diffused band, it was not visible clearly in the figure. Ethidium bromide staining of 28S and 18S ribosomal RNA of the same samples indicates equal RNA loading. (B) Quantitative analysis of hybridization signal obtained with PhosphorImager (n = 3). The symbols are as follows: C, control treated (basal medium alone); S, serum treated; F, bFGF treated.

Effect serum and bFGF on TFPI mRNA accumulation in PASMC. Quiescent PASMC were treated with basal medium alone or the basal medium containing serum (10% vol/vol) or bFGF/heparin (10 ng/15 U/mL) for 8, 24, and 48 hours. Total RNA was isolated from the cells, 10 μg of each RNA sample was used for Northern blot analysis, and the blot was hybridized with a radiolabeled TFPI cDNA probe and exposed to x-ray film (A). Because the TFPI 1.4-kb message in these cells was about 20% of the total TFPI message and migrated as a diffused band, it was not visible clearly in the figure. Ethidium bromide staining of 28S and 18S ribosomal RNA of the same samples indicates equal RNA loading. (B) Quantitative analysis of hybridization signal obtained with PhosphorImager (n = 3). The symbols are as follows: C, control treated (basal medium alone); S, serum treated; F, bFGF treated.

Because quiescent PASMC were found to express TFPI, we used these cells to determine the half-life of TFPI mRNA. Quiescent PASMC were treated with actinomycin-D (2.5 μg/mL) to inhibit transcription, and the decay of TFPI mRNA with time was analyzed by Northern blot analysis. The data showed that TFPI mRNA in PASMC appeared to decrease very slowly, and the apparent half-life appears to be between 48 and 72 hours (data not shown). Because prolonged treatments of PASMC with actinomycin-D resulted in significant cell death, we were unable to determine the half-life of TFPI mRNA in a more quantitative manner.

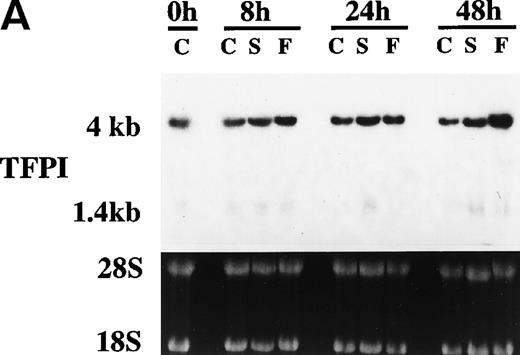

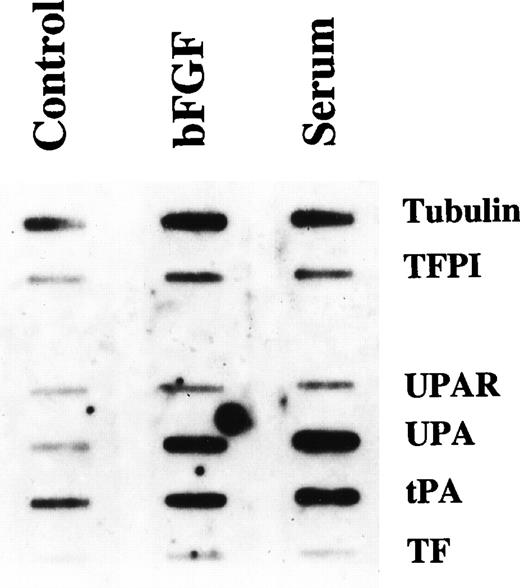

Effect of serum or bFGF/heparin on the transcription of TFPI.

Although, as described above, Northern blot analysis of TFPI mRNA accumulation failed to show a significant increase in the steady-state levels of TFPI mRNA in PASMC treated with serum or bFGF/heparin, it is possible that serum or bFGF/heparin could have exerted their effect on TFPI gene transcription. We, therefore, sought to determine if treatment with bFGF/heparin or serum enhanced the transcription rate of TFPI gene. Nuclear run-on experiments were performed to compare the rate of TFPI transcription in control quiescent PASMC and PASMC treated with serum or bFGF/heparin. As shown in Fig8, minimal transcription of TFPI was observed in control PASMC, and the rate of transcription of TFPI gene was minimally changed after either serum or bFGF/treatment. Quantitation of hybridization signal using a PhosphorImager showed only a 10% to 20% increase in TFPI gene transcription (corrected to transcription of house-keeping gene, tubulin) in cells treated with bFGF/heparin or serum. In a positive control, the transcription urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) gene was increased by 4.5- to 13-fold upon treatment with bFGF/heparin and serum, respectively.

Effect of serum and bFGF on nuclear run-on transcription of TFPI gene. Quiescent monolayers of PASMC were treated with control basal medium (Control), bFGF/heparin (10 ng/15 U/mL), or serum (10% vol/vol) for 8 hours. Three identical blots containing TFPI and other target DNAs were hybridized with equal amounts of labeled transcripts of nuclear RNA. DNAs used were as follows: -tubulin (-Tub), TFPI, urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR), urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA), tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA), and TF.

Effect of serum and bFGF on nuclear run-on transcription of TFPI gene. Quiescent monolayers of PASMC were treated with control basal medium (Control), bFGF/heparin (10 ng/15 U/mL), or serum (10% vol/vol) for 8 hours. Three identical blots containing TFPI and other target DNAs were hybridized with equal amounts of labeled transcripts of nuclear RNA. DNAs used were as follows: -tubulin (-Tub), TFPI, urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR), urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA), tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA), and TF.

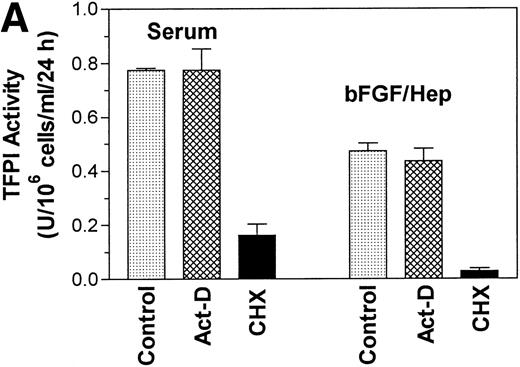

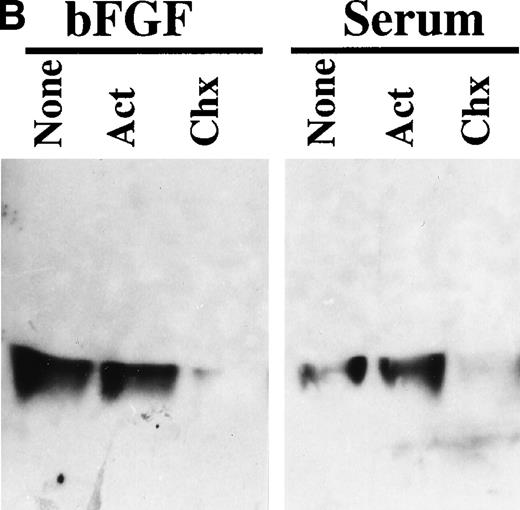

Effect of actinomycin-D and cycloheximide on upregulation of TFPI expression.

To examine the contribution of transcriptional and translational regulation to serum and bFGF-induced increase in TFPI activity, cells were treated with either serum or bFGF/heparin in the presence and absence of actinomycin-D and cycloheximide. As shown in Fig 9A, actinomycin-D had no significant effect on the serum and bFGF/heparin-induced TFPI activity, whereas cycloheximide markedly inhibited the serum and bFGF/heparin-induced TFPI expression. The data were further corroborated by Western blot analysis (Fig 9B), which showed a minimal decrease in TFPI antigen in the conditioned media from the cells treated with actinomycin-D before stimulation with either bFGF/heparin or serum. In contrast, no demonstrable TFPI antigen was secreted into the conditioned media if the cells were treated with cycloheximide before their stimulation.

Effect of actinomycin-D and cycloheximide on bFGF- and serum-induced TFPI expression. Quiescent PASMC monolayers were pretreated with actinomycin-D (5 μg/mL) or cycloheximide (10 μg/mL) for 1 hour and then treated with serum (10% vol/vol) or bFGF/heparin (10 ng/15 U/mL) for 24 hours. Conditioned media was assayed for TFPI activity (A) or analyzed for TFPI antigen by Western blot analysis (B). Control (in panel A) and none (in panel B) represent serum or bFGF/heparin treatments in the absence of inhibitor.

Effect of actinomycin-D and cycloheximide on bFGF- and serum-induced TFPI expression. Quiescent PASMC monolayers were pretreated with actinomycin-D (5 μg/mL) or cycloheximide (10 μg/mL) for 1 hour and then treated with serum (10% vol/vol) or bFGF/heparin (10 ng/15 U/mL) for 24 hours. Conditioned media was assayed for TFPI activity (A) or analyzed for TFPI antigen by Western blot analysis (B). Control (in panel A) and none (in panel B) represent serum or bFGF/heparin treatments in the absence of inhibitor.

DISCUSSION

Endothelial cells have been thought to be the primary source of TFPI within the vasculature.14 Megakaryocytes and macrophages are shown to express small amounts of TFPI, whereas circulating monocytes and fibroblasts express none to negligible amounts of TFPI.17 In this study, we show that human PASMC in culture constitutively synthesize and secrete TFPI. The levels of TFPI secreted by PASMC (60 mU/106 cells/mL/24 h) is relatively similar to the levels of TFPI secreted by endothelial cells (65 to 110 mU/106 cells/mL/24 h) but much higher than the level of TFPI secreted by human umbilical vein SMC (5 mU/106cells/mL/24 h).14,16 The difference in TFPI levels secreted by PASMC in the present study and the earlier study14 could be due to the difference in the vascular origin of SMC. Most of the TFPI synthesized in PASMC was secreted, with less than 10% being associated with cells. Although it had originally been thought that TFPI synthesized in endothelial cells is primarily associated with cells,23-25 recent data showed that virtually all TFPI synthesized in endothelial cells26,27 and vascular smooth muscle cells27 is secreted.

Little is known about how TFPI is regulated by the pulmonary vasculature. Earlier studies with endothelial cells failed to provide much information about the regulation of TFPI, because TFPI synthesis in these cells is minimally affected by inflammatory agents, such as TNF, IL-1, PMA, and LPS.16 In a preliminary report, Bajaj et al28 reported that serum stimulation of human fetal lung fibroblasts increased the expression of TFPI by sixfold. While the present manuscript was under review, Caplice et al27reported that serum stimulation of coronary vascular smooth cells resulted in a fivefold increase in TFPI antigen and activity levels in conditioned medium at 48 hours. A number of cytokine and growth factors, including IL-1, TGF-β, thrombin, and bFGF, have been implicated in the pathogenesis of hyperplasia of the arterial vascular wall. Therefore, we tested a range of cytokines and growth factors to define their ability to regulate the expression of TFPI in PASMC. Our data show that serum and bFGF/heparin caused a marked increase in the expression of TFPI activity, whereas other agents, such as thrombin, TNF-α, TGF-β, IL-1, and LPS, minimally increased the expression of TFPI. The increase in TFPI activity is associated with an increase in TFPI antigen levels. However, we found some discrepancy between TFPI activity and TFPI antigen levels. For example, we found a 12- to 15-fold increase in TFPI activity in cells treated with serum and bFGF, whereas the measurement of TFPI antigen levels showed a fivefold to sixfold increase. It is unlikely that the difference could be due to a possible contribution TFPI-2 to our functional activity assay, because monospecific anti-TFPI antibodies completely neutralized the VIIa/TF inhibitory activity of the conditioned media. Thus, the difference could be due to a difference in the sensitivity of the activity and the antigen assays. Although we cannot entirely rule out the possibility, it is unlikely that the specific activity of TFPI secreted by PASMC treated with serum or bFGF varies from the specific activity of constitutively expressed TFPI. Western blot analysis showed that both constitutively expressed TFPI and TFPI-induced by serum and bFGF were full-length and contain C-terminal domain.

The presence of heparin is required for bFGF to stimulate the expression of TFPI. One should note that heparin or bFGF treatment alone had no effect on the secretion of TFPI activity and total cell-associated TFPI levels. This rules out the possibility that bFGF/heparin-mediated increase in TFPI secretion stems from the release of cell-associated TFPI. Heparin was shown to potentiate FGF activity by either directly interacting with growth factor itself or with the FGF-receptor. It has been shown that heparin and heparan sulfate interact structurally with bFGF to induce conformational change in the polypeptide that stabilizes or increases its biological activity.29-31 Heparin has also been shown to decrease the kd for FGF binding to its receptor.31

Serum and bFGF-induced increase in TFPI expression in PASMC appears to involve transcriptional regulation to a very small degree. Northern blot analysis showed that PASMC constitutively express TFPI mRNA. The level of TFPI mRNA accumulation was not changed or only minimally increased after treatments with serum or bFGF for 8 and 24 hours, whereas the TFPI antigen and activity levels were increased by sixfold and 12-fold, respectively, after 24 hours of treatment. These data were further supported by nuclear run-on analysis that showed a minimal increase in the rate of activation of TFPI gene transcription. In addition, the inability of actinomycin-D to inhibit the increased levels of TFPI activity and antigen in serum- and bFGF-treated cells suggested that the regulation of TFPI could involve posttranscriptional or translational regulation. However, we cannot completely rule out some transcriptional regulation of TFPI, particularly in cells exposed to bFGF for prolonged periods, because we consistently observe a small increase in TFPI mRNA levels in these treatments.

Because TFPI mRNA appears to be relatively stable in the absence of any treatment32 (and present data), we inferred that it would be unlikely that an increase in TFPI mRNA stability could explain the increased expression of TFPI activity and antigen in serum-or bFGF-treated cells. Furthermore, we found no change in TFPI mRNA stability in serum- or bFGF-treated cells over 48 hours after transcriptional blockade. In addition, our data showed that cycloheximide, but not actinomycin-D, treatment fully inhibited both serum- and bFGF-induced increase in TFPI activity and TFPI antigen. Overall, these data suggest that the regulation of TFPI gene expression by serum and bFGF in PASMC is mainly regulated at the translational level. Further experiments are needed to establish the mechanism(s) by which serum and bFGF affects the translation of TFPI mRNA into a mature functionally active protein.

The observed effect of serum and bFGF on the expression of TFPI could be physiologically relevant in vascular remodelling associated with a number of diseases, including pulmonary hypertension and atherosclerosis. Several cytokines implicated in the pathogenesis of these diseases stimulate expression of TF in endothelial cells, macrophages, and SMC, and the aberrant expression of TF in these cells could lead to arterial thrombosis.3,5,7 Furthermore, thrombin10 and factor Xa,11 intermediary products generated in TF-pathway of coagulation, are shown to promote vascular smooth cell proliferation and thus may play a role in the development of intimal hyperplasia.7 Serum- and bFGF-stimulated expression of TFPI could inhibit the aberrant expression of TF activity, which could restore hemostasis and temper the factor Xa and thrombin-mediated proliferation of SMC. In this regard, it may be important to note that our recent studies showed that bFGF could suppress the aberrant expression of TF in endothelial cells.33 Both endothelial cells and SMC were shown to synthesize bFGF.34-36 Endothelial cell-derived bFGF is associated with endothelial cells, subendothelial cell extracellular matrix, and basement membrane.34 The denudation of endothelium associated with vascular injury allows the circulating constituents of plasma to access the media and also leads to the release of stored bFGF, which would then be available for SMC in neighboring intima.34,37,38 This bFGF could interact with heparin-like molecules produced by endothelial cells39 or derived from degradation of extracellular matrix and basement membrane.

In summary, our data provide evidence that SMC could synthesize and secrete functional TFPI, and the levels of TFPI synthesized by SMC are similar to those of endothelial cells, the cells that were thought to be the principal source of vascular TFPI. Our study also demonstrates, for the first time, that the expression of TFPI in SMC is regulated by serum and bFGF by a posttranscriptional mechanism. Serum- and bFGF-mediated upregulation of TFPI in SMC could be physiologically important for regulation of TF-coagulation pathway within the vessel wall and thereby influence the course of hyperplasia associated with pulmonary hypertension and atherosclerosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Jason Voigt for his technical assistance.

Supported in parts by Grants No. HL 45018 and HL 58869 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Usha R. Pendurthi, PhD, Department of Molecular Biology, The University of Texas Health Center at Tyler, 11937 US Highway 271, Tyler, TX 75708; e-mail: usha@uthct.edu.