Abstract

Partial deletion of the long arm of chromosome 5, del(5q), is the cytogenetic hallmark of the 5q-syndrome, a distinct subtype of myelodysplastic syndrome-refractory anemia (MDS-RA). Deletions of 5q also occur in the full spectrum of other de novo and therapy-related MDS and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) types, most often in association with other chromosome abnormalities. However, the loss of genetic material from 5q is believed to be of primary importance in the pathogenesis of all del(5q) disorders. In the present study, we performed fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) studies using a chromosome 5-specific whole chromosome painting probe and a 5q subtelomeric probe to determine the incidence of cryptic translocations. We studied archival fixed chromosome suspensions from 36 patients with myeloid disorders (predominantly MDS and AML) and del(5q) as the sole abnormality. In 3 AML patients studied, this identified a translocation of 5q subtelomeric sequences from the del(5q) to the short arm of an apparently normal chromosome 11. FISH with chromosome 11-specific subtelomeric probes confirmed the presence of 11p on the shortened 5q. Further FISH mapping confirmed that the 5q and 11p translocation breakpoints were the same in all 3 cases, between the nucleophosmin (NPM1) and fms-related tyrosine kinase 4 (FLT4) genes on 5q35 and the Harveyras-1–related gene complex (HRC) and the radixin pseudogene (RDPX1) on 11p15.5. Importantly, all 3 patients with the cryptic t(5;11) were children: a total of 3 of 4 AML children studied. Two were classified as AML-M2 and the third was classified as M4. All 3 responded poorly to treatment and had short survival times, ranging from 10 to 18 months. Although del(5q) is rare in childhood AML, this study indicates that, within this subgroup, the incidence of cryptic t(5;11) may be high. It is significant that none of the 24 MDS patients studied, including 11 confirmed as having 5q-syndrome, had the translocation. Therefore, this appears to be a new nonrandom chromosomal translocation, specifically associated with childhood AML with a differentiated blast cell phenotype and the presence of a del(5q).

IN ACUTE MYELOID leukemia (AML) the characteristic chromosome abnormalities are of two main types, which are believed to contribute to leukemogenesis in different ways.1 Balanced chromosome rearrangements (translocations or inversions) often result in the fusion of genes involved in regulation or differentiation, producing a chimeric protein with dramatically altered properties.2,3 Unbalanced chromosome rearrangements, particularly those involving chromosome loss or deletion, are believed to contribute to malignant transformation by the loss of tumor-suppressor function.4 Deletions of the long arm of chromosome 5, del(5q), are consistent cytogenetic findings in both de novo and therapy-related myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and AML. The incidence of 5q deletions is particularly high in leukemia arising as a late consequence of treatment of other malignant disease with alkylating agents.5-7 However, in all types of AML, del(5q) is usually found in association with other chromosome abnormalities.8 Del(5q) as a sole cytogenetic abnormality is one of the hallmarks of the 5q− syndrome, a distinct subtype of MDS with characteristic hematological features, including macrocytic anemia, modest leukopenia, normal or high platelet counts, and hypolobulated megakaryocytes.9,10 In contrast to del(5q) AML, the 5q− syndrome usually has an indolent clinical course, with a low rate of transformation to acute leukemia. Our previous studies indicate that the critical region of gene loss in 5q− syndrome patients is distinct from other critical deleted regions on 5q in other MDS and AML cases.11 12 This evidence all supports the notion that the 5q− syndrome is a distinct clinical entity.

Using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), we have previously found that a proportion of abnormalities reported by G-banding as deletions of chromosome 7, del(7q), are in fact cryptic translocations or other rearrangements involving the del(7q) chromosome.13Other studies have confirmed this for both 7q and 5q deletions, at least when these abnormalities are part of a complex karyotype.14 15 In the present study, we applied FISH with a whole chromosome 5 paint to a series of patients with myeloid disorders and del(5q) as a sole cytogenetic abnormality to determine whether simple del(5q) karyotypes also harbor cryptic translocations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Thirty-six patients with myeloid disorders (predominantly MDS and AML) and del(5q) as the sole abnormality were studied. These were referred from diagnostic cytogenetics laboratories in the United Kingdom and Europe. The majority of patients were adults, with only 5 being children. Twenty-four patients were diagnosed as MDS, of which 11 had the characteristic hematological features of the 5q− syndrome. Nine patients had AML, with 1 case of acute leukemia (unclassified), 1 of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), and 1 case of myeloproliferative disorder (MPD).

Probes

The probes used were as follows: (1) a commercially available biotinylated whole chromosome 5 painting probe (Cambio, Cambridge, UK); (2) chromosome 5 and 11p-specific cosmid and YAC probes (Table 1); (3) subtelomeric probes for 5p (cosmid 84C11), 5q (cosmid B22a4), 11p (cosmid 2209a2), and 11q (cosmid 2072c1)16; and (4) for the t(5;11) breakpoint mapping a 5p probe, cos 113-112 was used to identify both chromosomes 5 to ensure that metaphases being scored contained the del(5q).

FISH

For FISH studies, metaphases were prepared from 24-hour unstimulated bone marrow cultures or after overnight exposure to colcemid. Whole chromosome painting was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Cambio). FISH was performed essentially as previously described, using probes labeled with either biotin-16-dUTP or digoxigenin-11-dUTP.13 The hybridization mixture contained 100 ng labeled cosmid DNA or 400 ng labeled YAC DNA and 2.5 μg (for cosmids) or 7.5 μg (for YACs) unlabeled human Cot1 DNA. For the subtelomeric probes, hybridization was performed according to the Multiprobe protocol, using 4 ng each of the differentially labeled p and q arm subtelomeric probes and 0.25 μg Cot1 DNA in 2 μL hybridization buffer per square of the Multiprobe slide.17Dual-color detection was performed using the following layers: (1) avidin-Texas Red (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK) plus monoclonal antidigoxin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich Co Ltd, Dorset, UK), (2) biotinylated antiavidin plus rabbit antimouse Ig-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; Sigma-Aldrich Co Ltd), and (3) avidin-Texas Red plus monoclonal antirabbit-FITC (Sigma-Aldrich Co Ltd). Slides were mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories) containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 1.5 μg/mL). Results were analyzed using an Olympus BX-60 fluorescence microscope (Olympus Optical Co (UK) Ltd, London, UK) and images were captured using a cooled CCD imaging system and MacProbe version 3.3 software (Perceptive Scientific International, Chester, UK). At least 10 metaphases were evaluated for each probe used.

RESULTS

Identification of a Cryptic t(5;11)

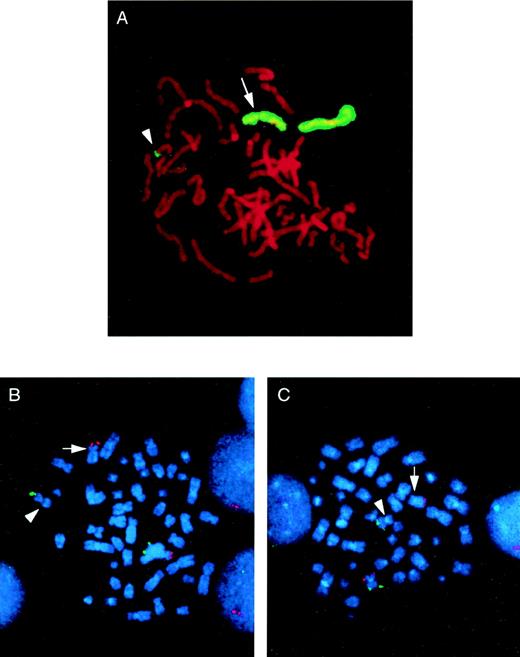

In 33 cases, the chromosome 5 whole chromosome painting probe highlighted only the del(5q) and the normal chromosome 5 homologue. In all of these, the del(5q) was confirmed as an interstitial deletion, with the 5q subtelomeric probe retained. Interestingly, in 3 AML cases, the chromosome 5 paint also highlighted the tip of the short arm of chromosome 11 (11p; Fig 1A). FISH with subtelomeric probes for 5p, 5q, 11p, and 11q confirmed the presence of 5q subtelomeric sequences on 11p and 11p subtelomeric sequences on the shortened 5q in all 3 cases (Fig 1B and C). This is therefore a cryptic translocation involving reciprocal exchange of 5q and 11p subtelomeric regions, with the 5q deletion and translocation occurring on the same chromosome 5. A partial G-banded karyotype of chromosomes 5 and 11 for all 3 patients is shown in Fig 2. Rescreening of the remaining 33 cases by FISH using the 5q and in some cases the 11p subtelomeric probe showed no further examples of the t(5;11).

Identification of a cryptic t(5;11) by whole chromosome painting and FISH with subtelomeric probes. (A) The whole chromosome 5 paint highlights the normal chromosome 5 homologue, the del(5q) (arrow), and the tip of an apparently normal chromosome 11 (arrowhead) in a metaphase from patient no. 3. Subtelomeric probes for 5p, 5q (B) and 11p, 11q (C) confirm the t(5;11) in metaphases from patient no. 2. In each case, the p arm subtelomeric probe is detected in Texas Red (red fluorescent signal) and the q arm subtelomeric probe is detected in fluorescein (green fluorescent signal). In both cases, the normal chromosome homologue has fluorescent signal corresponding to both the p and q arm subtelomeric probes. In (B), the del(5q) has only the p arm signal present (arrow), with the 5q subtelomeric probe present on the the short arm of the der(11) (arrowhead). Similarly, in (C), the der(11) (arrowhead) shows only the q arm signal, with the 11p subtelomeric probe sequences present on the del(5q) (arrow).

Identification of a cryptic t(5;11) by whole chromosome painting and FISH with subtelomeric probes. (A) The whole chromosome 5 paint highlights the normal chromosome 5 homologue, the del(5q) (arrow), and the tip of an apparently normal chromosome 11 (arrowhead) in a metaphase from patient no. 3. Subtelomeric probes for 5p, 5q (B) and 11p, 11q (C) confirm the t(5;11) in metaphases from patient no. 2. In each case, the p arm subtelomeric probe is detected in Texas Red (red fluorescent signal) and the q arm subtelomeric probe is detected in fluorescein (green fluorescent signal). In both cases, the normal chromosome homologue has fluorescent signal corresponding to both the p and q arm subtelomeric probes. In (B), the del(5q) has only the p arm signal present (arrow), with the 5q subtelomeric probe present on the the short arm of the der(11) (arrowhead). Similarly, in (C), the der(11) (arrowhead) shows only the q arm signal, with the 11p subtelomeric probe sequences present on the del(5q) (arrow).

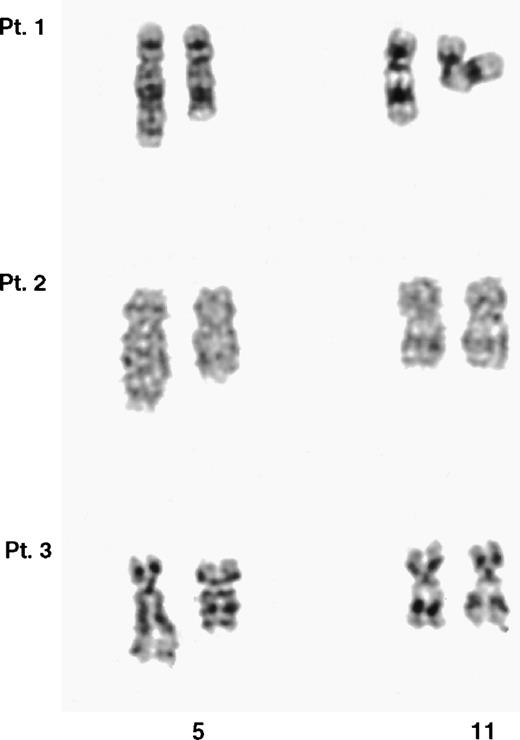

Partial G-banded karyotype of the chromosomes 5 and 11 from the 3 t(5;11) patients. In each case, the der(5) is shown on the right. It was not possible to unequivocally identify the der(11) in any of the 3 cases.

Partial G-banded karyotype of the chromosomes 5 and 11 from the 3 t(5;11) patients. In each case, the der(5) is shown on the right. It was not possible to unequivocally identify the der(11) in any of the 3 cases.

Clinical Reports of t(5;11) Patients

Patient no. 1.

Patient no. 1 was a 3-year-old female patient who presented with a six-week history of aching pains in her limbs and back. The blood count at presentation showed a hemoglobin (Hb) level of 2.8 g/dL, a white blood count (WBC) of 49 × 109/L, and a platelet count of 19 × 109/L. The bone marrow aspirate showed 70% blasts, which had Auer rods and was classified as AML-M2. She was treated on the MRC AML-10 trial and went into remission, but a hematological relapse was confirmed again after 4 months. She did not respond to further treatment and died 18 months after diagnosis.

Patient no. 2.

Patient no. 2 was a 3-year-old male patient who presented with a Hb level of 7.8 g/dL, a WBC of 113 × 109/L, a platelet count of 137 × 109/L, and 64% blasts in the peripheral blood. The bone marrow aspirate showed 71% blasts and a diagnosis of AML-M4 was made. Enlarged liver and spleen were seen at presentation. This child was treated according to the AML-BFM-87 protocol18 19 with additional HAM. Blasts were present after induction, consolidation, and additional HAM; therefore, this patient was classed as a nonresponder. He died 10 months after diagnosis.

Patient no. 3.

This 12-year-old male patient was referred to the hospital with suspicious appendicitis. The blood count at presentation showed a Hb level of 5.2 g/dL, a WBC of 520 × 109/L, 90% blasts, and a platelet count of 62 × 109/L. The bone marrow aspirate showed 77% blasts with Auer rods and a diagnosis of AML-M2 was made. Massive hepatosplenomegaly was seen at presentation. The patient was treated initially with leukapheresis and 5-hydroxyurea and subsequently with the ongoing AML-BFM-93 protocol. He died 10 months after diagnosis.

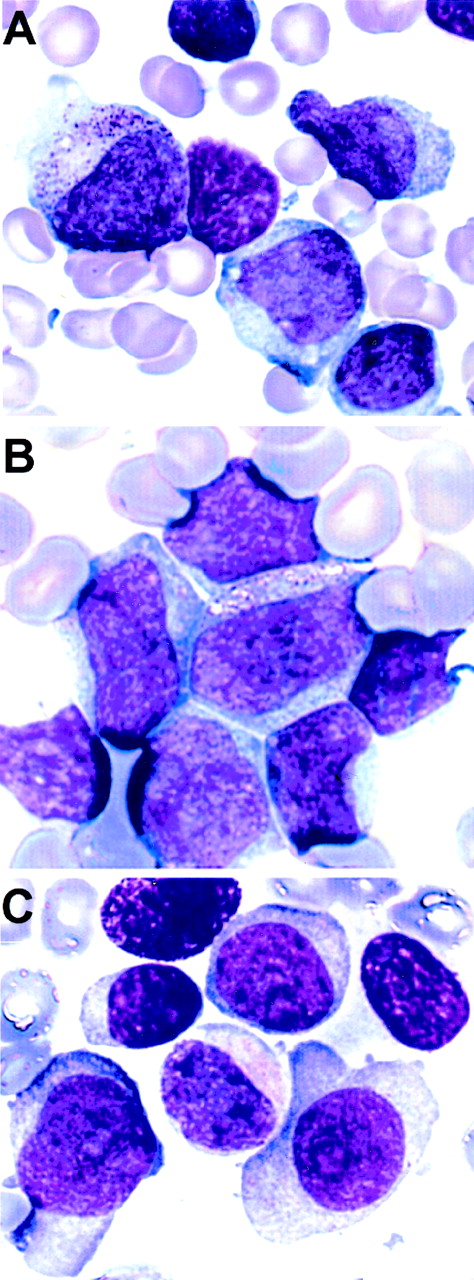

Representative images of May-Grünwald-Giemsa–stained bone marrow and peripheral blood smears from the 3 patients are given in Fig 3.

Morphology of the leukemic blasts from the 3 patients with a t(5;11). (A) Patient no. 1, bone marrow, AML-M2. (B) Patient no. 2, peripheral blood, AML-M4. (C) Patient no. 3, bone marrow, AML-M2.

Morphology of the leukemic blasts from the 3 patients with a t(5;11). (A) Patient no. 1, bone marrow, AML-M2. (B) Patient no. 2, peripheral blood, AML-M4. (C) Patient no. 3, bone marrow, AML-M2.

Localization of the 5q and 11p Breakpoints

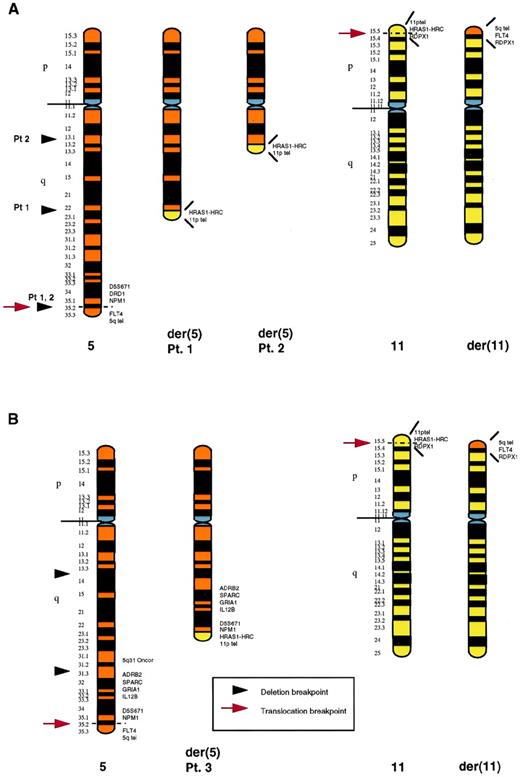

To further localize the distal breakpoint of the 5q deletion and the t(5;11) translocation breakpoints, we performed FISH with a series of cosmids and YACs from 5q31-q35 and 11p15.5 (Table 1). In 2 patients (nos. 1 and 2), the 5q translocation and distal deletion breakpoints were indistinguishable. In these 2 cases, probes immediately centromeric to the nucleophosmin (NPM1) gene were deleted from the der(5), with the fms-related tyrosine kinase 4 (FLT4) gene retained, but translocated to 11p15.5. In the third patient (no. 3), the distal breakpoint of the 5q deletion was between the 5q31 Oncor probe and the adrenergic receptor β2 (ADRB2) (5q31.3). In this case, the sequence corresponding to the 5q31 probe was deleted from the der(5), with the ADRB2, SPARC,GRIA1, IL12B, and NPM1 genes all present on the der(5). The FLT4 gene was also present, but was translocated to the der(11). Therefore, the 5q translocation breakpoint was within the same region in all 3 patients, between the NPM1 and FLT4genes. The 11p translocation breakpoint was also identical in all 3 patients, between the sequence corresponding to YAC yRP12a3 containing the pseudogene radixin (RDPX1) and cos 91G2 (containing the Harvey ras-1 gene, HRAS1, and HRAS1-related complex gene, HRC; http://shows.med.buffalo. edu20). An ideogram of the three rearrangements is given in Fig 4. The proximal breakpoints of the 5q deletion were not defined by FISH. However, based on banding studies and the size of the der(5), both the proximal breakpoint and the extent of the deletion was different in each case (Fig 4). The revised karyotype after FISH studies for all three cryptic translocation patients is given in Table 2.

Schematic representation of the rearranged chromosomes 5 and 11 in patients no. 1, 2 (A), and 3 (B). In each case, the normal chromosome homologue is shown on the left. The proximal breakpoints of the deletions are based on banding studies. In (A), the distal 5q deletion breakpoint and the 5q translocation breakpoint could not be distinguished: both were distal to NPM1. TheNPM1 gene sequence was deleted from the der(5), with theFLT4 sequence present, although translocated to the der(11). The 5q translocation breakpoint in (B) was also between theNPM1 and FLT4 genes. However, in this case, the 5q deletion was proximal to the translocation, with a distal breakpoint between the 5q31 probe and the ADRB2 gene (5q31.3). The 11p translocation breakpoint was the same in all 3 cases, between theHRC and RDPX1 genes on 11p15.5.

Schematic representation of the rearranged chromosomes 5 and 11 in patients no. 1, 2 (A), and 3 (B). In each case, the normal chromosome homologue is shown on the left. The proximal breakpoints of the deletions are based on banding studies. In (A), the distal 5q deletion breakpoint and the 5q translocation breakpoint could not be distinguished: both were distal to NPM1. TheNPM1 gene sequence was deleted from the der(5), with theFLT4 sequence present, although translocated to the der(11). The 5q translocation breakpoint in (B) was also between theNPM1 and FLT4 genes. However, in this case, the 5q deletion was proximal to the translocation, with a distal breakpoint between the 5q31 probe and the ADRB2 gene (5q31.3). The 11p translocation breakpoint was the same in all 3 cases, between theHRC and RDPX1 genes on 11p15.5.

DISCUSSION

We have identified a new nonrandom translocation, t(5;11)(q35;p15.5), involving translocation and deletion of the same chromosome 5 homologue, in a subset of AML children. This translocation is undetectable by conventional cytogenetic analysis and requires FISH for definitive identification. New multicolor karyotyping techniques, such as multiplex FISH (M-FISH) and spectral karyotyping (SKY), provide the promise of uncovering new nonrandom translocations associated with specific types of leukemia.21-23 Indeed, both M-FISH and SKY have already proven valuable in clarifying the origin of marker and unbalanced translocation chromosomes in tumor cell lines and leukemia.21-23 However, our results using M-FISH indicate that multicolor painting methods may be relatively insensitive for the detection of translocations involving telomeric regions.24Although the translocated segment of 5q was visible by single-color painting, the reciprocal piece of 11p on the der(5) was not detected using a chromosome 11-specific paint (results not shown). We believe that the t(5;11) would be difficult to detect unequivocally using the new multicolor karyotyping techniques. FISH with 5q and 11p-specific subtelomeric probes provides a more specific, sensitive alternative for the detection of this new rearrangement.

All 3 of the patients in whom we identified the t(5;11) were children with AML. None of the remaining 6 AML cases or any of the 24 MDS cases analyzed (including 11 with the specific clinical and hematological features of 5q− syndrome) had the translocation. The 3 children with the t(5;11) were classified according to the French-American-British (FAB) criteria as M2 (patients no. 1 and 3) and M4 (patient no. 2). Retrospective analysis of the bone marrow and peripheral blood smears by a single investigator showed some similarities (Fig 3). All 3 cases showed large blasts with more than one nucleolus and definite differentiation to promyelocytes. The two M2 cases were indistinguishable on morphological grounds, and both showed blasts with prominent eccentrically placed cytoplasm (Fig 3C). All 3 children had a poor response to treatment and short survival times, which were between 10 and 18 months. There were 2 other children with del(5q) in the study. These were a 4-year-old boy with MDS-RAEB and a 16-year-old boy with AML-M0. Although the numbers are small, it may be significant that the only AML child without the t(5;11) had no evidence of maturation in his leukemic blasts. We also used FISH with subtelomeric probes to screen apparently normal karyotypes in 4 AML children (results not shown). No cases of t(5;11) were found. Therefore, the t(5;11) appears to be specifically associated with the del(5q) aberration. The incidence of cryptic t(5;11) in AML children with a del(5q) appears to be high (3 of 4 in the present series) and associated with some blast cell differentiation. Screening of a larger series of AML children with del(5q) karyotypes is necessary to determine the true incidence of t(5;11) and to evaluate the characteristic clinical and hematological features.

The consistent translocation breakpoints on both 11p and 5q in the t(5;11) imply that this is an important event in the pathogenesis of the disease in these patients. The 11p15.5 breakpoint region (between the HRC and RDPX1 genes) is estimated to be 1.8 Mb. This region of 11p is of interest for a number of reasons. First, it contains the breakpoints for translocations and inversions in Beckwith-Wiedeman syndrome, a fetal overgrowth syndrome with predisposition to a range of embryonal tumors.25,26 Second, loss of heterozygosity for several loci within this region of 11p15.5 has been observed in a range of pediatric and adult tumor types.27-30 There is also an important cluster of imprinted genes within 11p15.5.31 Finally, the nucleoporin geneNUP98 lies at the centromeric end of the 11p15.5 breakpoint in the t(5;11). NUP98 is disrupted as a result of both the t(7;11)(p15;p15) (resulting in the NUP98/HOXA9 fusion) and inv(11)(p15q22) (NUP98/DDX10 gene fusion) in myeloid malignancies.32-34

The 5q35 breakpoint of the t(5;11) could not be precisely defined, because it lies within a 3-Mb gap in our YAC contig for 5q35.1-q35.3.35 The NPM1 gene, which is rearranged as a result of the t(3;5)(q25.1;q35) in a subset of MDS and AML cases,36 was found to be proximal to the breakpoint in the t(5;11) and therefore not involved. The tight association between the del(5q) and the t(5;11) implies a role for the deletion as well as the translocation in the development or progression of the disease in these patients. Identification of the critical genes involved in both the deletion and translocation events may shed some light on the pathogenesis of all del(5q) disorders.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Dr Norma Nowack (Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY) and Dr Larry Brody (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) for 11p15.5 probes; Prof Ursula Creutzig (Children’s University Hospital, Muenster, Germany) for the AML-BFM trial data; Prof Kevin Gatter and Robin Gant (John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK) for digital imaging of the bone marrow and peripheral blood smears; and Veronica Buckle for critical reading of the manuscript. The UKCCG Laboratories participating in the study were as follows: the ICRF Department of Medical Oncology, St Bartholomew’s Hospital (London, UK); the Centre for Human Genetics (Sheffield, UK); the Division of Human Genetics, University of Newcastle upon Tyne (Newcastle, UK); the Wessex Regional Genetics Laboratory (Salisbury, UK); the Cytogenetics Laboratory, Department of Haematology, Royal Free Hospital (London, UK); the Department of Medical Genetics, Belfast City Hospital (Belfast, UK); and Oxford Medical Genetics Laboratories, The Churchill Hospital (Oxford, UK).

Supported by The Leukaemia Research Fund, UK (R.J.J, J.B., J.M.B, and J.S.W), the Medical Research Council (L.K.), and Oesterreichische Kinderkrebsforschung (O.A.H.). B.W.K and U.M. were supported by the European Union (Contract GENE-CT93-0050 DG 12 SSMA).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Lyndal Kearney, PhD, MRC Molecular Haematology Unit, Institute of Molecular Medicine, John Radcliffe Hospital, Headington, Oxford OX3 9DS, UK; e-mail:lkearney@hammer.imm.ox.ac.uk.