Abstract

This study evaluated the anti-graft versus host disease (GVHD) potential of a combination of immunotoxins (IT), consisting of a murine CD3 (SPV-T3a) and CD7 (WT1) monoclonal antibody both conjugated to deglycosylated ricin A. In vitro efficacy data demonstrated that these IT act synergistically, resulting in an approximately 99% elimination of activated T cells at 10−8 mol/L (about 1.8 μg/mL). Because most natural killer (NK) cells are CD7+, NK activity was inhibited as well. Apart from the killing mediated by ricin A, binding of SPV-T3a by itself impaired in vitro cytotoxic T-cell cytotoxicity. Flow cytometric analysis revealed that this was due to both modulation of the CD3/T-cell receptor complex and activation-induced cell death. These results warranted evaluation of the IT combination in patients with refractory acute GVHD in an ongoing pilot study. So far, 4 patients have been treated with 3 to 4 infusions of 2 or 4 mg/m2 IT combination, administered intravenously at 48-hour intervals. The T1/2 was 6.7 hours, and peak serum levels ranged from 258 to 3210 ng/mL. Drug-associated side effects were restricted to limited edema, fever, and a modest rise of creatine kinase levels. One patient developed low-titer antibodies against ricin A. Infusions were associated with an immediate drop of circulating T cells, followed by a more gradual but continuing elimination of T/NK cells. One patient mounted an extensive CD8 T-cell response directly after treatment, not accompanied with aggravating GVHD. Two patients showed nearly complete remission of GVHD, despite unresponsiveness to the extensive pretreatment. These findings justify further investigation of the IT combination for treatment of diseases mediated by T cells.

Stem cell transplantation forms a widely accepted method for restoration of normal hematopoiesis of patients treated for a hematologic malignancy or otherwise suffering from a defective hematopoietic or immunologic system. For a successful engraftment, a minimal number of donor T cells in the graft appears to be a prerequisite. The underlying mechanism by which these cells promote engraftment is not fully understood, but probably includes the creation of an immunologically tolerogenic environment by eliminating the remainder of the patient's immune system.

In treatment of a malignancy, the cotransplantation of donor T cells confers additional benefit because they contribute to the so-called graft versus leukemia (GVL) effect, which involves the elimination of residual malignant cells.1 The basis of GVL forms the recognition by donor T cells of (minor or major) histocompatibility antigens expressed by the malignant recipient cells. Unfortunately, this antigenic disparity may also lead to graft versus host disease (GVHD), a major cause of morbidity and mortality after allogeneic stem cell transplantation.2 GVHD is thought to be initiated by alloactivation of donor T cells resulting in the production of cytokines (interleukin [IL]-2 and interferon [INF]-γ), which in turn activate additional effector cells, like monocytes, macrophages, and natural killer (NK) cells, to produce inflammatory proteins (IL-1, tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α, and IL-6).3 This may result in serious direct and indirect cytotoxicity to epithelial cells of skin, liver, and gut.

When prophylaxis has failed (typically cyclosporine, often combined with methotrexate), severe GVHD is usually treated with low-dose corticosteroids. If the reaction progresses, the dose may be increased (up to levels of 10-20 mg/kg/d) or, alternatively, polyclonal antithymocyte/antilymphocyte globulin (ATG/ALG) or experimental immunosuppressive drugs may be applied. An example of such an experimental reagent is Xomazyme-CD5 Plus, a murine CD5 monoclonal antibody (MoAb) conjugated to the A chain of the phytolectin ricin. Especially in the initial reports, Xomazyme-CD5 Plus demonstrated substantial efficacy in treating steroid-resistant acute GVHD.4,5 In more recent comparative trails, Xomazyme-CD5 Plus was not more effective than high-dose corticosteroids or ATG.6 7 Encouraged by its initial success, we developed a therapy based on the use of a combination of 2 anti-T-cell immunotoxins (IT): murine MoAb SPV-T3a (CD3) and WT1 (CD7), both conjugated to deglycosylated ricin A (dgA). We present the preclinical efficacy data and preliminary clinical results, both of which suggest that this IT combination has the potential for helping to control severe acute GVHD.

Materials and methods

Immunotoxins

The “IT combination” as referred to in this article consists of a 1:1 mixture (w/w) of murine MoAb SPV-T3a (CD3)8 and WT1 (CD7)9,10 both conjugated to dgA (Inland, Austin, TX) using the SMPT-cross-linker (Pierce, Rockford, IL), according to Ghetie et al.11 The preparation and validation were supervised by the institutional Department of Clinical Pharmacy. The major characteristics of the IT are summarized in Table1; details will be reported elsewhere (manuscript in preparation). Murine MoAb UPC-10 (IgG2a) and MOPC-141 (IgG2b) (both Sigma, St. Louis, MO) conjugated to dgA served as isotype-matched irrelevant controls for the in vitro experiments. Noteworthy, in vitro tissue screening unveiled a cross-reactivity of MoAb SPV-T3a with the basal epithelium of the human esophagus. To investigate potential in vivo consequences, the IT combination was administered to 2 cynomolgus monkeys sharing the same cross-reactivity. Subsequent esophagus biopsies revealed no toxicity toward the esophagus epithelium, nor could any localization of SPV-T3a-dgA be detected. Both monkeys demonstrated a transient rise of creatine kinase (CK)-levels on administration of the IT combination.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC)

PBMC were isolated from peripheral blood by Ficoll-Hypaque density centrifugation (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden), and cultured in Iscove's medium (Flow, Irvine, Scotland) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated pooled human serum (PHS), penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL). For generation of phytohemagglutinin (PHA)-activated T cells, PBMC were preincubated with 40 μg/mL PHA-HA15 (Murex, Dartford, UK) for 48 hours.

Flow cytometric quantification of in vitro cell kill

Nonactivated as well as PHA-activated PBMC (106/mL) were incubated in triplicate with varying concentrations of IT (10−13-10−8 mol/L) at 37°C for 24 hours. After treatment, cells were washed and cultured in the presence of PHA (40 μg/mL) for an additional 4 days to enable full exposure of IT toxicity. Subsequently, cells were labeled with propidium iodine (PI) (Molecular Probes, Junction City, OR) and calceinam (Calc) (Molecular Probes) (both: 2 μg/mL for 30 minutes at room temperature), and analyzed on a flow cytometer (Coulter Epics Elite, Hialeah, FL). Cells being PI− and Calc+ were referred to as viable cells. Prior to flow cytometric analysis, a fixed amount of inert beads (Flow-Count fluorospheres, Coulter) was added to each sample (1 × 104/mL) to enable the quantification of surviving cells.

Reduction of cytotoxic T-cell toxicity by SPV-T3a

Cytotoxic T-cell (CTL) toxicity was assayed in vitro using an EBNA3C12-reactive CTL clone. The CTL clone was incubated with MoAb SPV-T3a (10−8 mol/L) or isotype-matched control MoAb MOPC-141 at 37°C for 24 hours. Subsequently, cells were washed and cultured in culture medium for another 72 hours. Remaining cytolytic activity was assayed with an autologous Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-transformed lymphoblastoid cell line (EBV-LCL), labeled with 100 μCi 51Cr (Amersham, Bucks, UK) at 37°C for 2 hours. Labeled EBV-LCL were plated in triplicate (103/well) in V-bottom microtiter plates (Greiner, Fickenhausen, Germany) and saturated with endogenous EBNA3C (5 μmol/L for 1 hour at 37°C) to enhance T-cell receptor (TCR)-mediated lysis. Subsequently, varying numbers of MoAb-treated CTL cells were added to each well in a final volume of 150 μL culture medium. Plates were centrifuged (50g, 1 minute) and further incubated at 37°C. After 4 hours, 100 μL supernatant was collected from each well and counted in a gamma counter. Specific lysis was expressed as percentage maximal lysis by detergent, both corrected for spontaneous51Cr release.

Modulation of the CD3-antigen by SPV-T3a

Surface CD3 expression of SPV-T3a-treated CTL was determined by indirect fluorescence staining with a saturating amount of SPV-T3a (10 μg/mL, 4°C 30 minutes), followed by a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated F(ab′)2 goat-antimouse IgG (American Qualex International, La Mirada, CA). CD3 antigen still bound by SPV-T3a used for treatment was identified by staining with the FITC-conjugated antibody only. Expression was indicated as percentage relative to untreated control cells.

In vitro reduction of NK activity

The PBMC (106/mL) were incubated with 10−8 mol/L MoAb or IT for 24 hours. Subsequently, cells were washed and cultured for 3 additional days without MoAb/IT (to enable full exposure of toxicity). PBMC were serially diluted in 96-well U-bottomed plates, and a fixed concentration of51Cr-labeled K562 cells was added (104/well) to yield effector/target ratios of 10:1 to 0.37:1 in a final volume of 150 μL culture medium. Plates were centrifuged (50g, 1 minute) and further incubated at 37°C. After 4 hours, 100 μL supernatant was collected from each well and counted in a gamma counter. NK activity was expressed as percentage maximum lysis by detergent, both corrected for spontaneous 51Cr release. Recombinant IL-2 (500 U/mL) (Cetus, Emeryville, CA) was present during the entire assay to increase NK activity.

Clinical pilot study

The first patients were treated in a single center, nonrandomized, open-labeled, dose-escalating study (ongoing) with the aim of obtaining estimates of the safety and efficacy of the IT combination administered to patients with life-threatening GVHD. Patients with acute GVHD wereeligible if they had received second-line high-dose corticosteroid therapy (methylprednisolone 1000 mg/d) for at least 3 days without a decrease in the severity of clinical symptoms. Patients were not eligible if they had evidence of intrapulmonary disease (which might aggravate the clinical severity of vascular leak syndrome [VLS]13), or had allergy or antibodies to mouse Ig or dgA. Before entering the trial, all patients gave informed consent in accordance with the institutional review board and ethics committee. For assessment of safety and responses, patients were evaluated daily during hospitalization, and weekly thereafter, with a physical examination and by obtaining serum chemistries, complete blood counts, and leukocyte differential. In addition, blood samples were collected for determination of the pharmacokinetics and immunogenicity of the IT combination. Toxicities were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (NCI-CTC; version 2.0).

Administration of the IT combination

Patients were supposed to receive 4 doses of the IT combination administered intravenously in 4-hour infusions at 48-hour intervals. Prior to therapy, an intravenous test dose of 200 μg IT combination was administered to rule out anaphylactic reactions. Immunosuppressive agents used for prophylaxis and initial treatment of GVHD were allowed to remain unchanged.

Pharmacokinetics

Plasma levels of intact IT were measured with an enzyme immunoassay. Affinity-purified rabbit antiricin antibody (Sigma) in carbonate buffer (pH 9.6) was adsorbed to 96-wells maxisorp plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark), and residual binding sites were blocked with 4% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Patient plasma samples were serially diluted in 50% PHS in the absorbed microtiter plates and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. Subsequently, plates were washed and alkaline-phosphatase conjugated goat antimouse IgG2b or IgG2a (SBA, Birmingham, MI) was added at 37°C for 1 hour to bind captured SPV-T3a-dgA or WT1-dgA, respectively. Plates were washed and the reaction was developed using p-nitrophenylphosphate. Optical densities were read at 450 nm, and levels of circulating IT were calculated from standard curves obtained with a known concentration of IT combination diluted in pretreatment plasma. The detection limit was 0.02 μg/mL for both SPV-T3a-dgA and WT1-dgA. Plasma concentration versus time data were analyzed using the nonlinear least square regression program WinNonlin version 1.1 (Scientific Consulting, Apex, NC).

Measurement of human antimouse antibodies (HAMA) and human antiricin antibodies (HARA)

An enzyme immunoassay was used for detection of antibody responses to components of the IT combination. Patient plasma samples were serially diluted (undiluted to 1:2048) in phosphate-buffered saline with 1% human serum albumin in 96-well maxisorp plates (Nunc) containing either adsorbed SPV-T3a, WT1, or dgA. Bound human antibodies were probed using alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat antihuman IgG/IgM (H+L) antibodies (Jackson, West Grove, PA), and the reaction was developed with p-nitrophenylphosphate. Optical densities were read at 450 nm, and the serum titer was expressed as the end-point dilution. Positive titers were considered to be at least 3 times background.

Flow cytometry

Lymphocyte phenotyping was performed by multicolor flow cytometry using directly fluorescent-labeled MoAb according to a whole blood lysis method (FACS lysing, Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). T cells and NK cells were identified simultaneously with a mixture of fluorescence-labeled CD2 and CD5 MoAb (MT910-PE and DK23-PE, respectively) (DAKO, Copenhagen, Denmark). The percentage T/NK cells relative to all leukocytes was determined by costaining with a CD45-FITC MoAb (J33-FITC) (Immunotech, Marseille, France), and converted to absolute numbers based on the leukocyte count. B cells were quantified accordingly, using a PE-conjugated CD19 MoAb (HD37-PE) (DAKO).

Staging of GVHD and definitions of clinical responses

Each organ system was staged grade 1 through 4 acute GVHD according to established criteria.14 Patients were also given an overall grade of acute GVHD (I through IV) based on severity of organ involvement.14 Responses to therapy were defined as follows:

• Complete response (CR)—the disappearance of symptoms in all organ systems

• Partial response (PR)—the improvement of 1 organ or more, with no worsening in other organs

• Mixed response (MR)—the improvement of 1 organ or more, with worsening in 1 other organ or morexix

• Stable disease (SD)—no significant change in any organ system

• Progressive disease (PD)—progression in 1 organ system or more without improvement in other organs

Results

In vitro elimination of T cells

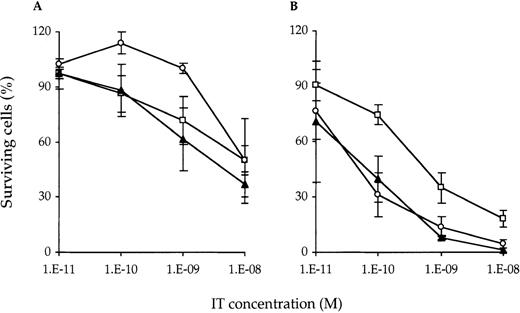

T cells may become more susceptible to dgA-IT on activation.15 This would be beneficial for the treatment of immunologic disorders. Ideally, such treatment inhibits ongoing or beginning immune responses without affecting the resting T-cell pool with its ability to counter future hazardous infections. To address this issue, nonactivated and PHA-activated PBMC were treated with IT for 24 hours and analyzed by flow cytometry for the number of surviving cells (Figure 1). Without prior PHA activation, treatment with SPV-T3a-dgA and WT1-dgA, either alone or in combination, resulted in a 2.0- to 2.7-fold reduction of viable cells at 10−8mol/L (about 1.8 μg/mL, the highest nontoxic concentration in vitro). After 48 hours of PHA activation, SPV-T3a-dgA, WT1-dgA, and the combination demonstrated an approximate 3-, 11-, and 34-fold increase in maximal killing capacity, respectively. The combination appeared very effective at concentrations above 10−9 mol/L, resulting in the elimination of 99% of activated T cells at 10−8 mol/L. Costaining with lineage-specific markers revealed no difference in vulnerability between CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets (data not shown). Neither incubation with isotype-matched control IT, nor with MoAb SPV-T3a or WT1, significantly reduced the number of viable cells (< 1.15-fold reduction at 10−8 mol/L; n = 3, data not shown).

Surviving T cells after treatement with IT.

Nonactivated (A) and PHA-activated (B) T cells were eliminated by SPV-T3a-dgA (□) and WT1-dgA (○), applied individually and in combination (▴) (half a dose each). Nonactivated and PHA-activated PBMC were incubated with various concentrations IT for 24 hours at 37°C. Following treatment, cells were washed and cultured for an additional 4 days in the presence of PHA to enable full exposure of IT toxicity. Subsequently, cells were stained with viability markers and analyzed by flow cytometry for the number of viable T cells relative to the untreated control. Data represent the mean ± SD as obtained with the PBMC of 3 healthy individuals.

Surviving T cells after treatement with IT.

Nonactivated (A) and PHA-activated (B) T cells were eliminated by SPV-T3a-dgA (□) and WT1-dgA (○), applied individually and in combination (▴) (half a dose each). Nonactivated and PHA-activated PBMC were incubated with various concentrations IT for 24 hours at 37°C. Following treatment, cells were washed and cultured for an additional 4 days in the presence of PHA to enable full exposure of IT toxicity. Subsequently, cells were stained with viability markers and analyzed by flow cytometry for the number of viable T cells relative to the untreated control. Data represent the mean ± SD as obtained with the PBMC of 3 healthy individuals.

Immunosuppressive activity of native MoAb SPV-T3a

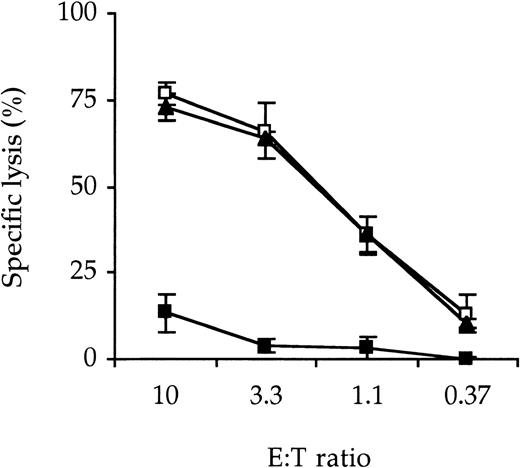

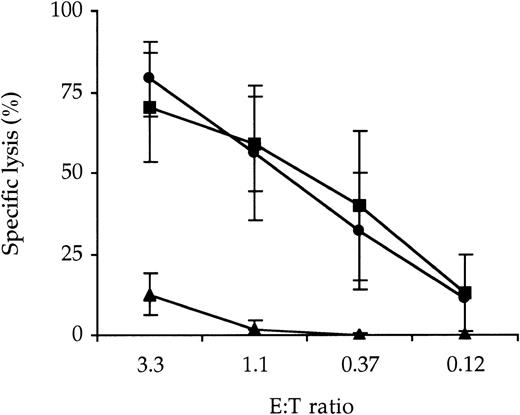

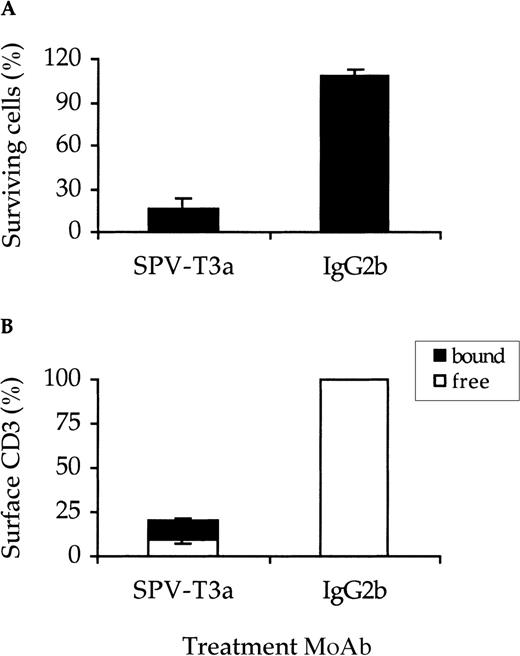

SPV-T3a may deliver an immunosuppressive effect, irrespective of its conjugation to dgA, by modulation of the T-cell receptor/CD3 complex (TCR/CD3 complex) or by induction of Fas-mediated apoptosis according to the process described as activation-induced cell death (AICD).16 To mimic the alloactivation induced in a transplantation setting, a CTL clone reactive with minor histocompatibility antigen, EBV-peptide EBNA3C, was stimulated with an autologous EBV-LCL. Incubation of this CTL with MoAb SPV-T3a for 24 hours abrogated almost completely its cytolytic activity as measured in a 51Cr-release assay (Figure2). Flow cytometric analysis (Figure3) revealed that this may be attributed to both (1) AICD of the CTL clone (to 16% of the untreated control) and (2) modulation of the CD3 antigen (to 20% of the untreated control). In addition, about half of the nonmodulated CD3 antigen was still occupied by SPV-T3a.

Reduction of CTL cytotoxicity by native MoAb SPV-T3a.

An EBNA3C-reactive CTL clone was incubated with 10−8mol/L MoAb SPV-T3a (▴), isotype-matched irrelevant MoAb MOPC-141 (◍) or culture medium (▪) for 24 hours at 37°C. Subsequently cells were washed and cultured for another 72 hours in culture medium. CTL cytotoxicity was then assayed by specific lysis of a51Cr-loaded autologous EBV-LCL and expressed as percentage relative to maximum lysis by detergent. Data represent the mean ± SD of 3 experiments performed in triplicate.

Reduction of CTL cytotoxicity by native MoAb SPV-T3a.

An EBNA3C-reactive CTL clone was incubated with 10−8mol/L MoAb SPV-T3a (▴), isotype-matched irrelevant MoAb MOPC-141 (◍) or culture medium (▪) for 24 hours at 37°C. Subsequently cells were washed and cultured for another 72 hours in culture medium. CTL cytotoxicity was then assayed by specific lysis of a51Cr-loaded autologous EBV-LCL and expressed as percentage relative to maximum lysis by detergent. Data represent the mean ± SD of 3 experiments performed in triplicate.

AICD and CD3-modulation by native SPV-T3a.

The EBNA3C-reactive CTL clone was incubated with 10−8mol/L MoAb SPV-T3a, or isotype-matched control MoAb MOPC-141, for 24 hours at 37°C. Subsequently, cells were washed and cultured for another 72 hours in culture medium. The number of surviving cells was then determined by viability staining and flow cytometric analysis, and expressed as percentage relative to the untreated control (A). Membrane expression of free and SPV-T3a-bound CD3-antigen was determined as described in Materials and methods and indicated as percentage relative to control cells (B). Data represent the mean ± SD of 3 experiments performed in triplicate.

AICD and CD3-modulation by native SPV-T3a.

The EBNA3C-reactive CTL clone was incubated with 10−8mol/L MoAb SPV-T3a, or isotype-matched control MoAb MOPC-141, for 24 hours at 37°C. Subsequently, cells were washed and cultured for another 72 hours in culture medium. The number of surviving cells was then determined by viability staining and flow cytometric analysis, and expressed as percentage relative to the untreated control (A). Membrane expression of free and SPV-T3a-bound CD3-antigen was determined as described in Materials and methods and indicated as percentage relative to control cells (B). Data represent the mean ± SD of 3 experiments performed in triplicate.

NK activity after IT treatment

Although initiated by CTL, GVHD is thought to be aggravated by less specific cytokine-stimulated “bystander cells” like NK cells.3,17 18 The capacity of the described MoAb or IT to reduce NK activity was assayed by inhibition of lysis of51Cr-loaded K562 cells. Figure4 shows the NK activity of PBMC incubated with IT for 24 hours. As expected, treatment with SPV-T3a-dgA did not affect the NK activity (NK cells being CD3−). In contrast, NK activity was almost completely abolished 3 days after incubation with WT1-dgA. Similar results were obtained with cell line Daudi, which is predominantly vulnerable for lymphokine-activated killer cells (data not shown). Neither nonconjugated MoAb WT1, nor isotype-matched control IT UPC-10-dgA, impaired the lysis of K562 or Daudi cells (data not shown, n = 3).

Effect of IT treatment on NK activity.

PBMC were treated with 10−8 mol/L WT1-dgA (▪) or SPV-T3a-dgA (▴) or without IT (□), for 24 hours at 37°C. After treatment, cells were washed and cultured for an additional 3 days in culture medium without IT. Subsequently, remaining NK activity was determined by specific lysis of 51Cr-labeled K562 blasts and expressed as percentage relative to untreated cells. During the experiment, 50 U/mL recombinant IL-2 was added to the culture medium to increase NK activity. Data represent the mean ± SD of 3 experiments performed in triplicate.

Effect of IT treatment on NK activity.

PBMC were treated with 10−8 mol/L WT1-dgA (▪) or SPV-T3a-dgA (▴) or without IT (□), for 24 hours at 37°C. After treatment, cells were washed and cultured for an additional 3 days in culture medium without IT. Subsequently, remaining NK activity was determined by specific lysis of 51Cr-labeled K562 blasts and expressed as percentage relative to untreated cells. During the experiment, 50 U/mL recombinant IL-2 was added to the culture medium to increase NK activity. Data represent the mean ± SD of 3 experiments performed in triplicate.

Pilot study participants

So far, 4 patients, all white men, have been enrolled in the study. The clinical features of these patients are summarized in Table2. Patients 1 and 2 have been treated at the lowest dose level (2 × 2 mg/m2 followed by 2 × 4 mg/m2) and patients 3 and 4 at the second dose level (4 × 4 mg/m2). Due to their early deaths, patients 1 and 4 received only 3 of the 4 planned infusions.

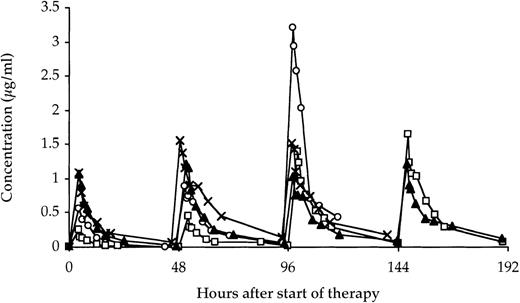

Pharmacokinetics

The plasma clearance curves best fitted a 1-compartment model with a constant rate infusion and a first-order elimination rate for both SPV-T3a-dgA and WT1-dgA individually and given in combination. The pharmacokinetic parameters determined over the entire courses are listed in Table 3. The mean T1/2 was 6.5 ± 2.4 hours for SPV-T3a-dgA, 7.5 ± 1.7 hours for WT1-dgA, and 6.7 ± 2.1 hours for the IT combination. Peak plasma levels were attained directly after each infusion and decreased (nearly) to baseline level in about 48 hours (Figure 5). The maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) for the IT combination ranged from 258 ng/mL after the first dose for patient 2 (2 mg/m2) to 3210 ng/mL after the third dose for patient 1 (4 mg/m2). The latter seemed to be an exception because the maximum peak plasma level in the other patients fell within the relative narrow range of 1220 to 1650 ng/mL (all attained after a dose of 4 mg/m2). The 2-fold higher level in patient 1 may be explained by his aggravating multiorgan failure interfering with the IT plasma clearance. When comparing the separate infusions, the mean T1/2 of the IT combination almost doubled over the complete treatment course (Table4). This may be explained by a reduction of available target antigens, which act as an antigen sink especially during the first infusion(s).

Plasma clearance curves.

IT combination plasma clearance curves are shown from patient 1 (treated with 2, 2, and 4 mg/m2) (○); patient 2 (2, 2, 4, and 4 mg/m2) (□); patient 3 (4, 4, 4, and 4 mg/m2) (▴); and patient 4 (4, 4, and 4 mg/m2)5 (×). IT combination plasma concentrations were deduced by summation of the individual values as determined for SPV-T3a-dgA and WT1-dgA.

Plasma clearance curves.

IT combination plasma clearance curves are shown from patient 1 (treated with 2, 2, and 4 mg/m2) (○); patient 2 (2, 2, 4, and 4 mg/m2) (□); patient 3 (4, 4, 4, and 4 mg/m2) (▴); and patient 4 (4, 4, and 4 mg/m2)5 (×). IT combination plasma concentrations were deduced by summation of the individual values as determined for SPV-T3a-dgA and WT1-dgA.

Safety

The adverse events noted during the first 6 weeks following initiation of therapy are listed in Table5. Because of the advanced disease of the patients, the etiology of the observed clinical events was obscured by multiple medical complications and concomitant medications. Patients 1 and 4 died during therapy due to worsening of complications already existing before start of the treatment, patient 1 from progressive multiorgan failure and patient 4 from generalized aspergillosis in combination with a cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Symptoms thought to be related to the IT combination were mild and transient. Patient 1 demonstrated edema in his shoulder not associated with weight gain, potentially due to limited capillary leakage. Patient 3 experienced episodes of fever during and between the IT combination infusions. This fever may have been caused by a viral infection as well (see biologic responses). Patient 4 demonstrated a rise of plasma CK levels (not accompanied by myalgia) to 280 U/L on day 9 of therapy, being 1.45 times the upper limit of the normal range for men. The increase was not accompanied by a rise in the heart muscle isomer creatine kinase MB (CK-MB). Patient 4 had aphasia of short duration (< 1 hour) 1 day after the first infusion of the IT combination. At that time he was taking cyclosporine and had hemolysis with high reticulocyte counts, progressive thrombocytopenia, and fragmented red cells in the blood smear. It was concluded that aphasia was associated with cyclosporine-induced thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) and was not caused by the IT combination (aphasia has been reported as a side effect of other immunotoxins19-21). Cyclosporine was withdrawn and aphasia did not recur despite the further administration of the IT combination.

Immunogenicity

Patient plasma samples were measured frequently before, during, and after the trial for HAMA and HARA. No antibodies against SPV-T3a nor WT1 were detected in any of the cases. Patient 4 demonstrated a weakly positive HARA titer, 8 times the pretreatment value, on day 8 (1 day before his death).

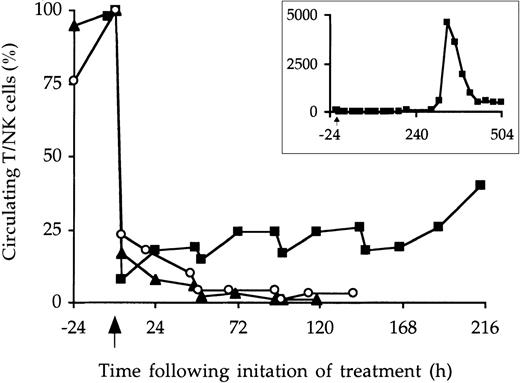

Biologic responses

Biologic responses were monitored by flow cytometric evaluation of circulating T cells or NK cells or both. The concentrations of NK cells were too low to enable a reliable quantification with NK-specific markers. Therefore, NK cells and T cells were identified simultaneously using a mixture of a fluorescent-labeled CD2 (binding T cells and NK cells) and a CD5 MoAb (binding T cells). Figure 6 shows the amount of circulating T/NK cells expressed as a percentage relative to the concentration at start of therapy. Patient 2 could not be adequately monitored due to the low initial number of circulating T/NK cells (about 6 × 107/L). All 3 evaluable patients already demonstrated a remarkable reduction of T/NK cells during the first administration of the IT combination. Immediately after the 4 hours of infusion, the number of circulating T/NK cells of patients 1, 3, and 4 had dropped to 17%, 8%, and 24% of the pretreatment level, respectively. For patients 1 and 4, this number gradually declined to 1% to 3% after the third infusion. Patient 3, in contrast, showed signs of a rebound of NK/T cells between the infusions. After the last infusion, a progressive expansion of T/NK cells was observed resulting in a peak concentration of about 45 times the pretreatment value at day 14. Flow cytometric analysis with CD4/CD8 MoAb and a T-cell receptor Vβ-panel pointed out that these cells were virtually all CD8+ and oligoclonal in origin. At day 18, the number of T cells had decreased again to about 5 times the pretreatment level (probably by apoptosis as suggested by annexin staining, data not shown). These observations, combined with the episodes of fever patient 3 experienced during the first week, are suggestive of a T-cell response after a viral infection.

Number of T/NK cells after IT combination treatment.

Patients 1 (▴) and 4 (○) received 3 and patient 3 (▪) received all of the 4 planned IT combination doses, given as 4-hour infusions at 48-hour intervals. The arrow beneath the x axis indicates the start of the first infusion. T/NK cells were identified by being CD2+ or CD5+ or both. Their number was expressed as percentage relative to the concentration at start of therapy (being 0.7, 1.0, and 0.2 × 109 cells/L for patients 1, 3, and 4, respectively). The inlay figure represents the amount of T/NK cells of patient 3 as determined over a longer period.

Number of T/NK cells after IT combination treatment.

Patients 1 (▴) and 4 (○) received 3 and patient 3 (▪) received all of the 4 planned IT combination doses, given as 4-hour infusions at 48-hour intervals. The arrow beneath the x axis indicates the start of the first infusion. T/NK cells were identified by being CD2+ or CD5+ or both. Their number was expressed as percentage relative to the concentration at start of therapy (being 0.7, 1.0, and 0.2 × 109 cells/L for patients 1, 3, and 4, respectively). The inlay figure represents the amount of T/NK cells of patient 3 as determined over a longer period.

The slow B-cell repopulation following stem cell transplantation prevented a reliable quantification of circulating B cells in patients 1, 2, and 3. The concentration of peripheral blood B cells of patient 4 showed a normal biologic fluctuation (0.1- 0.2 × 109/L), which was not affected by the IT combination. Moreover, the complete blood counts and leukocyte differential of all patients revealed no toxicity toward any of the other hematopoietic lineages (data not shown), thereby illustrating the selectivity of treatment for T/NK cells.

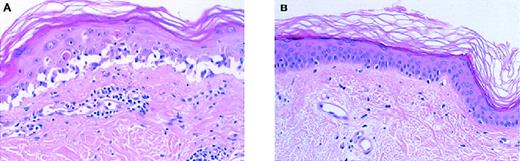

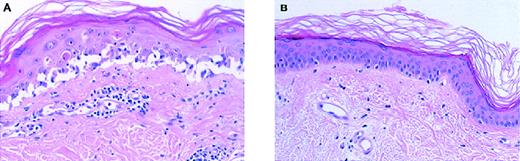

Skin biopsy specimens from patient 2 clearly demonstrated the biologic efficacy of the IT combination treatment (Figure7). The microscopic appearance before treatment is typical for severe acute GVHD, with scattered infiltration of lymphocytes and a severely affected epidermal basal layer. After treatment, no remaining signs of lymphocyte infiltration could be detected, and the basal epidermis had regained its natural well-organized configuration. The intestinal GVHD of patient 3 was confirmed by a biopsy from the colon performed at day −5 (grade 3). When repeated at day 31, biopsy demonstrated a marked reduction of lymphocyte infiltrates without further signs of active GVHD. In patient 4 only a postmortem liver sample could be taken. Microscopic analysis revealed extensive cholestasis. Notably, no infiltrating lymphocytes could be detected.

Skin biopsy specimens.

Skin biopsies were obtained from patient 2 just before (A) and 2 weeks after (B) treatment with the IT combination. The appearance of the skin before treatment is typical for severe GVHD. A scattered infiltration of lymphocytes can be observed, localized primarily around the blood vessels and the junctional region of dermis (lower side) and epidermis (upper side). The epidermal basal layer is destroyed and the epidermis is disrupted from the basal lamina. Following treatment, no remaining signs of lymphocyte infiltrations were detectable. The basal layer had regained its natural well-organized configuration (original magnification × 100, hematoxylin-eosin).

Skin biopsy specimens.

Skin biopsies were obtained from patient 2 just before (A) and 2 weeks after (B) treatment with the IT combination. The appearance of the skin before treatment is typical for severe GVHD. A scattered infiltration of lymphocytes can be observed, localized primarily around the blood vessels and the junctional region of dermis (lower side) and epidermis (upper side). The epidermal basal layer is destroyed and the epidermis is disrupted from the basal lamina. Following treatment, no remaining signs of lymphocyte infiltrations were detectable. The basal layer had regained its natural well-organized configuration (original magnification × 100, hematoxylin-eosin).

Clinical responses

Patient 1 showed a slight but clear improvement of his skin, from grade 4 to 3, starting at day 4. His (abnormal) liver functions remained stable; his gastrointestinal tract could not be objectively monitored due to administration of morphine. After 7 days of therapy, he died as a consequence of multiorgan failure. Patient 2 showed a dramatic reduction of his grade 4 GVHD of the skin to grade 0/1, starting 4 days after the first infusion and lasting for about 1.5 months. He then developed a modest relapse, GVHD grade 2 of the skin, which responded well to standard therapy with relatively low-dose corticosteroids supplemented with UV-B radiation. Patient 2 died 8 months after the IT combination administration due to generalized aspergillosis and toxoplasmic encephalitis. Patient 3 showed strong improvement of his intestinal GVHD, grade 2 to grade 0, within 7 days after initiation of therapy. Apart from a mild and controllable GVHD reaction of his skin, grade 1 to 2 responding to low-dose corticosteroids, he showed no further signs of active GVHD. Two months after initiation of therapy, patient 3 died of a bacterial infection. Patient 4 showed a more or less stable GVHD of his liver during the 7 days of treatment. He died from a generalized aspergillosis in combination with a CMV infection on day 8.

Discussion

The in vitro efficacy data demonstrate that simultaneous application of SPV-T3a-dgA and WT1-dgA results in a synergistic cytotoxicity, leading to an approximately 99% elimination of activated T cells. A comparable synergism has been described for other IT combinations as well.15,22-28 The most obvious advantage above single IT treatment is that fewer target cells will be negative for multiple antigens than for a single antigen. In addition, the cells that express substantial levels of multiple target antigens may be loaded with more IT molecules. When the respective IT follow a different intracellular routing, the chance to escape the cytotoxic activity of the IT may be further reduced. With respect to anti-T-cell IT, reports addressing the combination approach are thus far focused on in vitro applications, including the purging of bone marrow grafts.15 22-24 In this resport, we state that the combination of SPV-T3a-dgA and WT1-dgA appears appropriate for the in vivo elimination of unwanted T cells as well. This particular combination affords important benefits that surpass the “common synergism” as observed with the combinations of anti-T-cell IT described so far.

SPV-T3a was selected as CD3 MoAb based on its IgG2b-isotype which strongly reduces the risk of cytokine release syndrome.29,30 The presence of a CD3-IT provides instant immunosuppression independent of dgA-based cytotoxicity (Figures 2 and3). This may be of vital importance in vivo during treatment of acute life-threatening situations such as refractory GVHD. The limited (AICD) as well as temporal nature (blocking and modulation of CD3/TCR) of the underlying mechanisms provide arguments for making a “real killer” of SPV-T3a by conjugating it to dgA. The inclusion of the CD7-IT is essential, apart from the above-mentioned synergism, because it makes NK cells a target for the IT combination as well (Figure 4). Accumulating evidence points to a distinctive role of NK cells in the pathophysiology of GVHD.17 18

The pioneer work of Vitetta and colleagues was of great value in designing the clinical pilot study. They thoroughly studied the in vivo efficacy of RFB4-dgA (CD22) and HD37-dgA (CD19) in treating patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma in relation to different dose regimens.13,20,21,31-33 In the present study, 4 patients with refractory acute GVHD have been treated with individual doses of 2 or 4 mg/m2 IT combination, according to their intermittent bolus infusion protocol. The mean T1/2 of SPV-T3a-dgA and WT1-dgA resembled those of RFB4-dgA and RFB5-dgA (6.1-7.8 hours), the latter being a CD25-IT for the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma.34 The blood clearance of these IT is more than twice as fast as reported for HD37-dgA (T1/2 of 18.2 hours). As with RFB4-dgA and RFB5-dgA, the clearance appeared to be influenced by circulating target cells. In contrast to RFB4-dgA and RFB5-dgA, this did not result in large interpatient variations. Instead, the T1/2 of the IT combination increased about 2-fold during the entire treatment course, probably due to (1) the rapid elimination of “MoAb-capturing” target cells (Figure 6), or (2) by a reduction of available binding sites per cell (modulation/occupation). The latter possibility especially holds true for CD3 (see also Figure 3B). The CD7 antigen, in contrast, demonstrates a rapid re-expression of free antigen, resulting in the restoration of pretreatment expression levels within 48 hours (in vitro and in vivo observations, data not shown). Three patients suffered from severe GVHD that was more or less restricted to the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and liver, respectively. Their relative narrow-ranged T1/2 and Cmax demonstrate that the type of organ involved has no major impact on the pharmacokinetics. The single exception was the patient suffering from a generalized GVHD (affecting skin, liver, and gastrointestinal tract) in combination with a severe kidney failure. His about 2-fold higher Cmax may reflect a different IT handling due to his worsening multiorgan failure.

In 3 patients, Cmax exceeded 1.2 to 1.6 times and in 1 patient Cmax exceeded 3.5 times the “clinically save threshold level” as defined for RFB4-dgA and HD37-dgA (1 μg/mL).13,20,32 Drug-related toxicities appeared to be restricted to limited capillary leakage and a modest rise of CK levels (both n = 1). This may be the result of the IT combination encompassing 2 distinct IT, each having a different spectrum of side effects (resulting in a distribution and, thereby, reduction in severity of drug-related toxicities). This is in agreement with observations of Vallera et al35 and Onda et al,36 who both reported on comparable IT (directed against the same target cell/antigen and containing the same toxin), that displayed different toxicity profiles when tested in the same mouse model. None of the 4 patients treated with the IT combination developed detectable HAMA. Only 1 patient showed a positive HARA titer (8 times baseline level). Apart from the small population size, this may be attributed to the huge dosages of corticosteroids administered and to incomplete reconstitution of the B-cell compartment early after transplantation.

The design of the pilot study does not allow an estimation of long-term toxicities (eg, increase in opportunistic infections or secondary malignancies). Three of the 4 patients treated so far eventually died of an infection. The IT combination cannot be excluded as a contributing factor to the underlying immunosuppression. However, a realistic long-term safety profile can only be obtained when the IT combination is applied without extensive preceding and concomitant second-line medication. At least theoretically, based on its short T1/2 and narrow specificity range, the IT combination is expected to accomplish a relatively limited immunosuppression by only temporarily affecting the T/NK cell compartment. Moreover, the composition of the IT combination is better defined and expected to vary less than that of ATG/ALG,37-39 which use is often associated with sustained T-cell depletion.40,41 From this viewpoint, it appears encouraging that the third patient showed a strong oligoclonal T-cell expansion directly after treatment with the IT combination. The presumed antiviral T-cell response was not associated with a relapse of GVHD. This suggests a strong immunogenicity of the respective antigen or some form of treatment selectivity toward activated cells. The latter is in agreement with the in vitro observations and might be explained by the fact that on activation T cells show an increased expression of the CD7 target-antigen9,10 and become vulnerable for CD3-triggered AICD.42 43

All patients showed a response, ranging from the elimination of the majority of circulating T/NK cells, to the dramatic clinical responses as observed in the patients 2 and 3. The biphasic pattern of T/NK cell removal indicates that multiple mechanisms are involved, some of which have not been observed in vitro. As for the in vitro efficacy data, the IT combination needs several days before it displays its full killing capacity. This is in accordance with observations of Beyers et al,5 who reported that it took 5 daily infusions of H65-ricin A (CD5) to achieve a more or less gradual reduction of T cells to 20% of the initial number. In contrast, the IT combination induced in vivo a massive and rapid reduction of T/NK cells already during the first 4 hours of infusion. Comparable biologic responses have been described for native murine MoAb,44-46 including anti-CD3/TCR MoAb of IgG2b isotype.47 48 The underlying mechanism is not fully clear yet. Some indirect evidence is provided that MoAb SPV-T3a is responsible for this initial rapid T-cell reduction. Tax and colleagues (unpublished observation, W.J.M.T.) demonstrated that nonconjugated MoAb WT1 did not influence the number of circulating T cells when administered in vivo to renal patients for the treatment of graft rejection. In addition, flow cytometry analysis of blood samples of the first patient demonstrated that the minor population of CD3−CD7+ cells (mostly NK cells) was reduced at a much slower rate (up to 2 days) than the CD3+CD7+ T cells (data not shown). In general, reduction of lymphocytes by native murine MoAb is often transient, a few days or less. In the present study, the initial rapid elimination was followed by a more gradual but sustained reduction of T/NK cells. This suggests a dgA-based elimination of target cells, which is supported by the in vitro killing capacity of the IT combination observed at concentrations obtained in vivo.

It is impossible from the clinical data to determine the exact contribution of SPV-T3a-dgA and WT1-dgA (or their MoAb moieties) to the observed biologic and clinical responses. Unfortunately, no animal models are available that allow an efficacy evaluation of the individual components (SPV-T3a does not bind monkey-CD3). The high tolerability of the IT combination argues against the clinical testing of theoretically less effective individual components (being single IT or MoAb). Instead, further studies should be focused on elucidating the full potency of the IT combination in its present form. Apart from dose optimization and application in an earlier phase of GVHD, this may include the treatment of alternative indications that potentially benefit from the in vivo elimination of T cells.

The authors are aware of the limited nature of the clinical data obtained so far. However, the major finding that emerged from these data is that the IT combination concept might work. Substantial biologic as well as clinical responses have been observed in the absence of acute severe toxicities. This is especially meaningful considering the extensive pretreatment of the enrolled patients. Ideally, further studies will point out that the IT combination forms a safe and effective tool for helping control certain diseases mediated by T cells.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr Harry Dolstra who generously provided the EBNA3C-reactive CTL-cell clone, to Dr Elly van de Wiel-van Kemenade for helpful advice throughout the project, and to Arie Pennings, Cathy Maass, Mary Leenders, and Jacky Greene for technical assistance.

Supported in part by a grant from the Technology Foundation STW, Nieuwegein, The Netherlands (NGN55.3949).

Reprints:Ypke van Oosterhout, Department of Hematology, University Hospital St Radboud, Geert Grooteplein 8, 6525 GA Nijmegen, The Netherlands; e-mail: y.vanoosterhout@chl.azn.nl.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.