Using mice deficient of E-selectin and E/P-selectin, we have studied the requirement for endothelial selectins in extravasation of leukocytes at sites of viral infection, with major emphasis on the recruitment of virus-specific TC1 cells. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV)–induced meningitis was used as our primary experimental model. Additionally, localized subdermal inflammation and virus clearance in internal organs were analyzed during LCMV infection. The generation of CD8+ effector T cells in infected mutants was unimpaired. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of the inflammatory exudate cells in intracerebrally infected mice gave identical results in all strains of mice. Expression of endothelial selectin was also found to be redundant regarding the ability of effector cells to eliminate virus in nonlymphoid organs. Concerning LCMV-induced footpad swelling, absent or marginal reduction was found in E/P-sel −/− mice, compared with wild-type mice after local challenge with virus or immunodominant viral MHC class I restricted peptide, respectively. Similar results were obtained after adoptive transfer of wild-type effector cells into E/P-sel −/− recipients, whereas footpad swelling was markedly decreased in P-sel/ICAM-1 −/− and ICAM-1 −/− recipients. LCMV-induced footpad swelling was completely inhibited in ICAM-deficient mice transfused with donor cell preincubated with soluble VCAM-1-Ig chimeric protein. Taken together, the current findings strongly indicate that the migration of TC1 effector cells to sites of viral infection can proceed in the absence of endothelial selectins, whereas ligands of the Ig superfamily are critically involved in this process.

Leukocyte rolling is considered a pivotal element in the multistep cascade leading to cell extravasation at sites of inflammation.1,2 Rolling is mediated primarily by adhesion molecules belonging to the selectin family that comprises 3 members2: P- and E-selectin expressed on vascular endothelium and L-selectin expressed on leukocytes. All 3 members are cell surface molecules with a common structure containing an N-terminal lectin domain with a high affinity for certain glycosylated ligands. P-selectin is constitutively found in secretory granules of platelets and endothelial cells and on activation is rapidly mobilized to the plasma membrane.3,4 Moreover, transcription is upregulated in cytokine-activated endothelial cells in vivo.5 In contrast, E-selectin is only transcriptionally regulated and appears on the cell surface a few hours after exposure to cytokines.6,7 The third member, L-selectin, is found on most leucocytes8 and is involved in leukocyte rolling in addition to serving as the primary adhesion receptor for lymphocyte entry into peripheral lymph nodes.9-11 Several studies have suggested that P- and E-selectins are at least partially redundant and can replace each other at inflammatory sites in vivo.2,12 13

The use of neutralizing antibodies and genetic engineered mice with null mutations in the genes encoding E-, P-, or E/P-selectin have clearly evidenced the importance of these molecules in leukocyte extravasation and inflammatory reactions.2,13 From a functional point of view, it has been found that E/P-selectin deficient (E/P-sel −/−) mice are more susceptible to cutanous bacterial infections14,15 and show an impaired resistance to intraperitoneal challenge with Streptococcus pneumoniae, in addition to deficiency of leukocyte rolling and recruitment.14 In addition, altered hematopoiesis is observed in E/P-selectin −/− mice.15 In contrast, selectins seem to play only a minimal role in recruitment of leukocytes into inflamed liver microvasculature,16 and migration of neutrophils to lung alveoli can occur in the absence of all selectins.17

Few in vivo studies have been performed specifically addressing the role of endothelial selectins in recruitment of T cells to sites of inflammation. Migration of CD4+ T cells into inflamed skin is found to be dependent on expression of E- and P-selectin18,19 and, in addition, evidence has been presented indicating that P- and E-selectin may be critically involved in preferential recruitment of TH1 versus TH2 cells.20 Similarly, oxazolone-induced contact hypersensitivity, which is believed to be initiated by recruitment of TH1 cells, has been shown to be reduced in P-selectin deficient mice and almost absent in E- and P-selectin double mutant mice.21,22 However, to our knowledge similar specific information is not available for CD8+ effector T cells. Concerning the recruitment of mononuclear cells to the central nervous system (CNS), varied results have been obtained. Thus, CD4+lymphocytes appear to cross the blood-brain barrier independently of E- and P-selectin expression in mice with experimental autoimmune encephalitis.23 However, the influx of leukocytes in cytokine-induced meningitis has been shown to be severely impaired in E- and P-selectin double mutant mice.24

In the current study, the role of endothelial selectins in recruitment of leukocytes to infected sites during viral infection was analyzed, with a major emphasis on the recruitment of virus-specific TC1 cells (CD8+ T cells secreting the same cytokines as TH1 cells25). TC1 cells are a major arm of the antiviral host response, and play a significant role in the acute clearance of many viruses acting as killer cells and/or as local producers of antiviral cytokines, eg, interferon-γ.26,27 The model system applied was the murine lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection. LCMV is a noncytopathic virus that causes little or no inflammation in the absence of a virus-specific T-cell response.28,29 In immunocompetent mice, however, the appearance of effector T cells is associated with substantial inflammation in infected organs, and intracerebral (ic) infection leads to a fatal T-cell–mediated meningitis that has become a classical model for virus-induced immunopathologic disease.30 Previous studies have revealed that the inflammatory exudate consists mainly of activated CD8+ T cells and monocytes/macrophages, whereas it contains very few CD4+ T lymphocytes30; moreover, an inflammatory response is virtually absent in CD8-deficient mice.29 In vitro analysis of exudate cells has further disclosed that most recruited T cells are producers of interferon-γ, but not IL-5 or IL-10,31 and this cytokine profile matches the profile found in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of ic-infected mice.32,33 Thus, the effector T cells mediating LCMV-induced inflammation clearly belong to the TC1 subtype.31,34 Whereas we have previously established a role for integrins (VLA-4, LFA-1, Mac-1) and their ligands (VCAM-1, ICAM-1) in recruiting CD8+ effector cells to sites of infection,35-38 the importance of local expression of selectins in this process is unknown.

Using primarily E-selectin deficient mice and E/P-selectin double deficient mice,14 we have studied the LCMV-induced inflammatory response assessed as susceptibility to ic infection and as footpad swelling after local challenge. Because clearance of LCMV is a direct result of effector T-cell homing to infected organs,39 40 virus elimination was used as an additional parameter for the efficiency and functional impact of the inflammatory response. We found the expression of endothelial selectins to be redundant concerning the formation, composition, and magnitude of the inflammatory exudate. Also with regard to the clinically relevant parameters such as susceptibilty to ic infection and virus clearance, endothelial selectins appeared superfluous. Consequently, our findings strongly indicate that the migration of TC1 effector cells to many sites of viral infection can proceed without local expression of selectins, and that TH1 and TC1 may differ in their requirements for extravasation.

Materials and methods

Mice

E/P-selectin deficient (E/P-sel −/−) and E-selectin deficient (E-sel −/−) mice14 were the progeny of breeder pairs kindly provided by Daniel Bullard, University of Alabama, whereas P-selectin (P-sel −/−) and P-selectin/ICAM-1 (P-sel/ICAM-1 −/−) deficient mice were obtained directly from the Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME. All knockout strains were on a C57BL/6 background, and wild-type C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Bomholtgaard Ltd, Ry, Denmark. Seven- to 10-week-old mice were used in all experiments, and animals from outside sources were always allowed to acclimatize to the local environment for at least 1 week. All animals were housed under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions as validated by testing of sentinels for unwanted infections, according to the Federation of European Laboratory Animal Science Association guidelines.

Virus

LCMV of the Traub strain, produced and stored as previously described,41 was used in all experiments. Mice to be infected intracerebrally (ic) received a dose of 103LD50 in a volume of 0.03 mL. This route of inoculation results in a fatal T-cell–mediated meningitis from which the animals succumb 6 to 8 days after infection (pi).30,38 Mice to undergo systemic infection were given the same virus dose intravenously (iv) in a volume of 0.3 mL. This type of inoculation results in a transient, immunizing infection.42

Virus titration

Virus titrations were carried out by ic inoculation of 10-fold dilutions of 10% organ suspension into young adult Swiss mice. Titration endpoints were calculated by the Kärber method and expressed as mean lethal doses (LD50).

Survival study

Mortality was used to evaluate the clinical severity of acute LCMV-induced meningitis. Mice were checked twice daily for a period of 14 days or until 100% mortality was reached.

Assay of LCMV-specific delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH)

Three different approaches were used to assess LCMV-specific DTH. (1) Mice were infected locally in the right hind footpad (fp) with 103 LD50 of LCMV, and the local swelling reaction was followed between day 6 and 17 pi. (2) Mice were infected iv with the same dose of virus and challenged in the right hind footpad with 30 μL of an immunodominant class I restricted peptide (LCMV GP33-41, 50 μg/mL) on day 8 pi; footpad swelling was measured 16, 24, 48, and 72 hours later. (3) Mice were inoculated in their right hind fP with 30 μL of virus containing 103 LD50 of LCMV. Four hours later they were injected iv with 5 × 107 splenic lymphocytes from wild-type donors, infected 8 days previously with the same dose of virus iv. Donor cells were routinely treated with mitomycin C (25 μg/mL, to prevent secondary expansion in the recipients) and depleted of plastic adherent cells by incubation for 1 hour at 37°C in tissue culture flasks. Footpad thickness was measured 16, 24, 48, and 72 hours after cell transfer, and to compensate for interexperimental variation wild-type recipients given the same donor cells were always included as a positive standard. Footpad thickness was measured with a dial caliper (Mitutoyo 7309, Mitutoyo Co, Tokyo, Japan), and virus-specific swelling was determined as the difference in thickness of the infected/challenged right and the uninfected/unchallenged left foot.42 43

Inhibition of adoptive DTH response with soluble VCAM-1-Ig chimeric protein (sVCAM-1)

LCMV-primed donor splenocytes treated as described previously were incubated with sVCAM-144(kindly provided by L. Burkly, Biogen Inc, Cambridge, MA) or human IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for control (0.5 mg/108 cells/mL) for 30 minutes before injection into preinfected recipients (see above).

Cell preparations

Spleens were removed from mice killed by ether anesthetization. Single-cell suspensions were obtained by pressing the organs through a fine steel mesh, and erythrocytes were lysed by 0.83% NH4Cl treatment (Gey's solution). CSF exudate cells were obtained from the fourth ventricle of mice that had been ether anesthetized and exsanguinated; background level in uninfected mice is < 100 cells/μL.29 43

Cytotoxic assays

Virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (TC) activity was assayed in a standard 51Cr-release assay using histocompatible MC57G cells infected with LCMV for 48 hours as specific targets; uninfected MC57G cells served as control targets. Assay time was 5 hours, and percent specific release was calculated as described previously.41 42

Monoclonal antibodies

The following mAb were all purchased from PharMingen (San Diego, CA) as rat antimouse antibodies: FITC conjugated anti-CD49d (common α-chain of LPAM-1 and VLA-4, R1-2), phycoerythrin (PE) conjugated anti-CD8a,53–67 biotin conjugated anti-CD62L (L-selectin, MEL-14), PE conjugated anti-CD162 (P-selectin glycoprotein-1, PSGL-1, 2PH1), FITC conjugated anti-Mac-1 (M1/70), and PE conjugated anti-IFN-γ (XMG1.2).

Flow cytometric analysis

One × 106 cells were stained with labeled mAbs in staining buffer (1% rat serum, 1% bovine-serum albumin [BSA], 0,1% NaN3 in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) for 20 minutes in the dark at 4°C and subsequently washed. Cells incubated with biotin-conjugated Ab were further incubated with steptavidin-Tri-color (Caltag Laboratories, San Francisco, CA) and washed. After washing twice, cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyd. For visualization of LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells, splenocytes (107 cells/mL) were incubated with an immunodominant MHC class I–resticted epitope (LCMV GP 33-41, 0.1 μg/mL), monensin (3 μmol) and IL-2 (100 IU/mL) for 5 hours, after which cells were surface labeled and fixed. Then the cells were permeabilized using PBS/saponin (0.05%), and anti-IFN-γ was added. After incubation for 20 minutes in the dark, cells were washed twice in PBS/saponin.31 Samples were analyzed using a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA), and 1 to 2 × 104viable mononuclear cells were gated using a combination of forward angle and side scatter to exclude dead cells and debris. Data analysis was carried out using the Cell Quest program, and results are presented as contour plots.45

Results

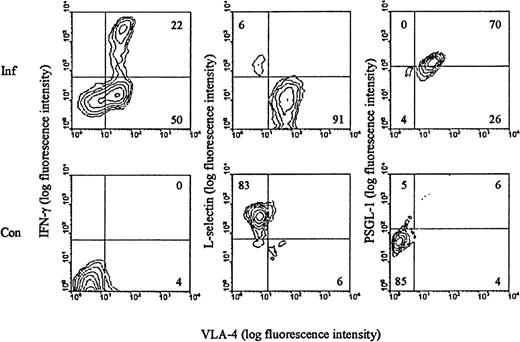

Cell surface phenotype of LCMV-activated T cells

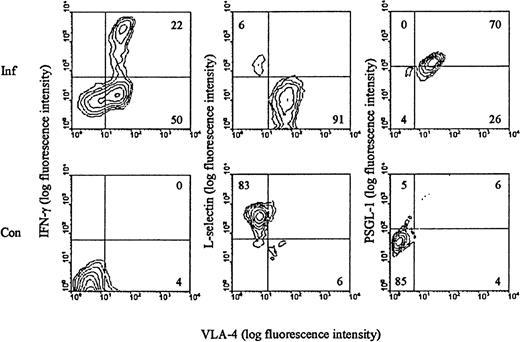

We have previously shown that LCMV infection induces the generation of a large subset of CD8+ T cells with an activated phenotype (CD44high LFA-1highVLA-4high L-sellow) and capacity to exert effector functions (cytolysis and IFN-γ release) (reviewed in Thomsen et al34). Most, if not all, of the expanded T-cell population represents antigen-specific cells as recently disclosed through staining with specific peptide/MHC class I tetramers.46 To evaluate these cells with regard to their ability to participate in selectin-dependent binding, splenocytes from day 8–infected mice were analyzed for expression of L-selectin and PSGL-1, the best described receptor for P-selectin.47 In addition, the surface phenotype of LCMV-specific T cells was visualized through brief stimulation with an immunodominant LCMV-derived peptide (LCMV GP 33-41), followed by staining for IFN-γ intracellularly. Our results (Figure 1) revealed, as expected, that all LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells are of the VLA-4high phenotype. In addition, we confirm that these cells express low levels of L-selectin. In contrast, the level of PSGL-1 was found to be increased on a large proportion of activated CD8+ T cells. As CD8+ T cells found at sites of inflammation are recruited exclusively from this activated subset (data not shown), we considered it pertinent to study the role of endothelial selectins in targeting of effector T cells to sites of infection.

Surface phenotype of LCMV-activated CD8+ T cells.

C57BL/6 mice were infected iv with 103 LD50 of LCMV, and on day 8 pi splenocytes were harvested (Inf). Cells were stained with anti-CD8-PE, anti-VLA-FITC, and either anti-IFN-γ, anti-L-selectin, or anti-PSGL-1. Spleen cells from uninfected mice were used as control (Con). Results representative of analyses of 3 to 5 mice/group are depicted.

Surface phenotype of LCMV-activated CD8+ T cells.

C57BL/6 mice were infected iv with 103 LD50 of LCMV, and on day 8 pi splenocytes were harvested (Inf). Cells were stained with anti-CD8-PE, anti-VLA-FITC, and either anti-IFN-γ, anti-L-selectin, or anti-PSGL-1. Spleen cells from uninfected mice were used as control (Con). Results representative of analyses of 3 to 5 mice/group are depicted.

LCMV-induced CD8+ T cell activation in E/P-sel −/− and E-sel −/− mice

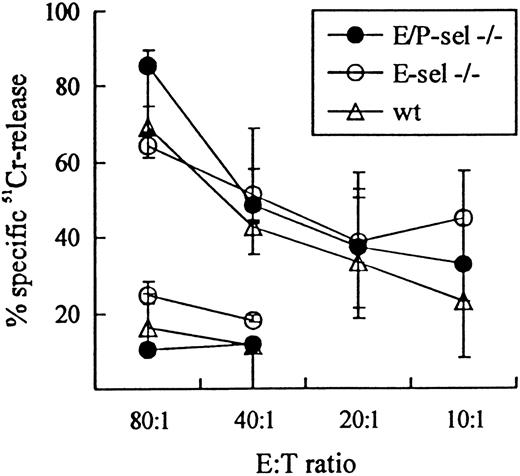

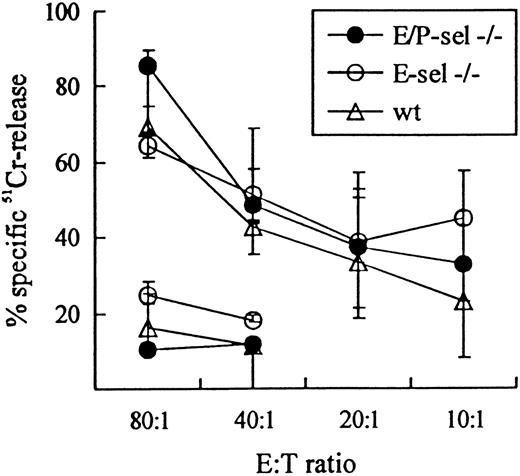

To validate the use of E-sel −/− and E/P-sel −/− mice in the analysis of CD8+T-cell–mediated inflammatory reactions, initial experiments were carried out to ascertain that there was no impairment in the ability of these mice to generate effector T cells belonging to this subset. Functional analysis of the effector cell capacity in mutant mice compared with wild-type mice revealed an unimpaired virus-specific cytotoxic T-cell response, as there was no significant difference in the ability of splenic T cells to lyse virus-infected MC57G target cells 8 days after iv infection with LCMV in either E/P-sel −/− or E-sel −/− compared with wild-type mice (Figure 2). Direct visualization of antigen-specific T cells through detection of IFN-γ+cells gave similar results (data not shown). Furthermore, because the inflammatory response in LCMV-infected mice has previously been found to directly correlate with the number of activated CD8+ T cells generated in the spleen,35 45 the frequency of splenic CD8+ T cell with this phenotype (VLA-4high) was analyzed in ic-infected mice on day 7 pi. The number of activated CD8+ T cells tended to be higher in E-sel −/− mice and slightly lower in E/P-sel −/− mice compared with wild-type mice (21% [15%-21%], 30% [27%-33%], and 26% [14%-30%] for E/P-sel −/−, E-sel −/− and wild type mice, respectively, medians (and ranges) of 4 mice), but none of these differences were statistically significant. Thus, the generation of CD8+ effector T cells seems to be unimpaired in infected mice lacking expression of endothelial selectins, allowing direct comparison of leukocyte migration to infected sites between these animals and wild-type mice.

LCMV-specific TC activity in E/P-sel −/−, E-sel −/−, and wild-type (wt) C57BL/6 mice 8 days after iv infection.

Mice were infected iv with 103 LD50 of LCMV, and splenic TC activity was assayed using MC57G cells infected 48 hours previously LCMV. Uninfected MC57G cells, assayed only at effector:target (E:T) ratio 80:1 and 40:1 were used as negative controls. Medians and ranges of 3 mice per group are depicted.

LCMV-specific TC activity in E/P-sel −/−, E-sel −/−, and wild-type (wt) C57BL/6 mice 8 days after iv infection.

Mice were infected iv with 103 LD50 of LCMV, and splenic TC activity was assayed using MC57G cells infected 48 hours previously LCMV. Uninfected MC57G cells, assayed only at effector:target (E:T) ratio 80:1 and 40:1 were used as negative controls. Medians and ranges of 3 mice per group are depicted.

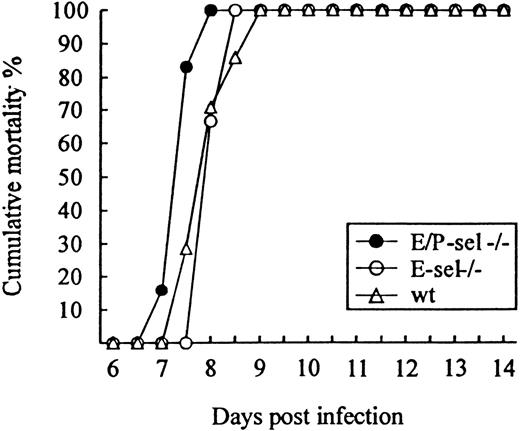

Role of endothelial selectins in the outcome of IC infection with LCMV

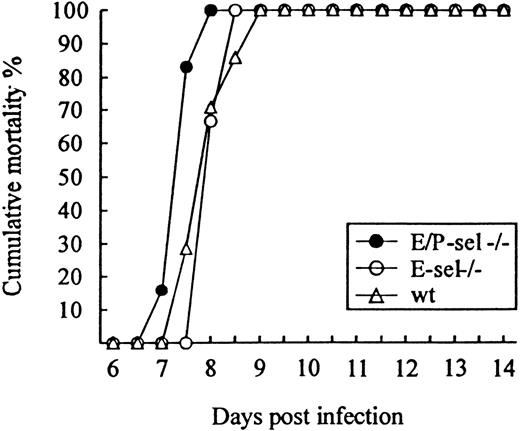

To study the role of E- and P-selectin in the recruitment of lymphocytes to the LCMV-infected meninges, E/P-sel −/−, E-sel −/−, and wild-type mice were infected ic with 103 LD50 of LCMV and clinical susceptibility to meningitis, measured as mortality, was determined. Surprisingly, both groups of mutant mice developed LCMV-induced meningitis and succumbed to the infection to the same degree as did wild-type mice (Figure3); if anything, E/P-sel −/− mice tended to die earlier than wild-type mice. Quantitative and qualitative analyses of the cellular exudate were performed in parallel. No significant differences in the number of mononuclear cells contained in the CSF were revealed either on day 6 or 7 pi, and the composition of the inflammatory exudate with regard to CD8+T cells and Mac-1+ monocytes/macrophages was found to be similar in all 3 strains of mice (Table 1). Altogether, the above findings indicate that recruitment of virus-activated CD8+ T cells to the LCMV-infected meninges do not require local expression of endothelial selectins.

Absence of selectins do not influence the time course or outcome of ic infection.

E/P-sel −/−, E-sel −/−, and wild-type (wt) mice were infected ic with 103 LD50 of LCMV, and mortality was registered. Groups consisted of 6 to 7 mice.

Absence of selectins do not influence the time course or outcome of ic infection.

E/P-sel −/−, E-sel −/−, and wild-type (wt) mice were infected ic with 103 LD50 of LCMV, and mortality was registered. Groups consisted of 6 to 7 mice.

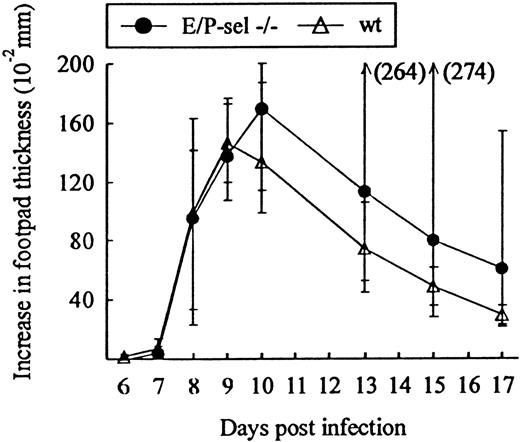

Virus-induced DTH in the absence of endothelial selectins

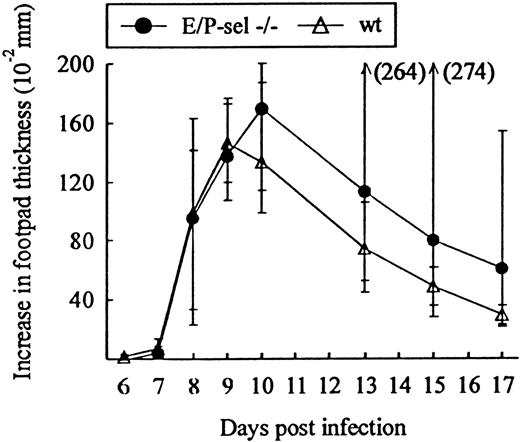

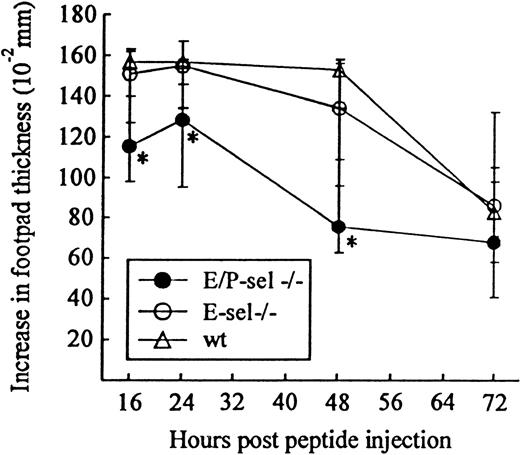

Another classical model of LCMV-induced CD8+T-cell–mediated inflammation is the primary footpad swelling reaction that is the response to subdermal viral challenge.43,48,49To study the role of endothelial selectins in this DTH-like reaction, E/P-sel −/− mice and wild-type B6 mice were infected in the right hind footpad with 103 LD50 of LCMV, and footpad swelling was measured between day 6 and 17 pi. No significant difference in the response pattern of mutants and wild-type mice was observed (Figure 4), indicating that, also, this subdermal inflammatory response could proceed in the absence of endothelial selectins. However, a relatively high degree of interindividual variation is intrinsic to this type of assay and this may mask minor differences in the kinetics. Some of the interindividual variation is likely to result from small variations in local virus replication and the time point of subsequent generalized virus spread. Therefore, we additionally measured the response of iv-infected mice to local challenge (on day 8 pi) with an immunodominant viral MHC class I–restricted peptide (LCMV GP33-41); previous results have clearly established that this is a valid way of assessing CD8+ T-cell dependent responses.33 50 Under these conditions, a slightly reduced response was observed in E/P-sel −/− mice, but not in E-sel −/− mice (Figure5). However, in all mice, a very substantial inflammatory reaction was induced, and similar results were obtained in mice primed 2 months earlier (data not shown), demonstrating that the redundancy of endothelial selectins did not simply result from the high number of recently activated effector cells present in mice undergoing acute infection.

Time course of footpad swelling in E/P-sel −/− and wild-type (wt) mice after local LCMV infection.

Mice were infected with 103 LD50 of LCMV in the right hind footpad, and footpad swelling was measured from day 6 to 17 pi. Groups consisted of 6 mice; medians and ranges are presented.

Time course of footpad swelling in E/P-sel −/− and wild-type (wt) mice after local LCMV infection.

Mice were infected with 103 LD50 of LCMV in the right hind footpad, and footpad swelling was measured from day 6 to 17 pi. Groups consisted of 6 mice; medians and ranges are presented.

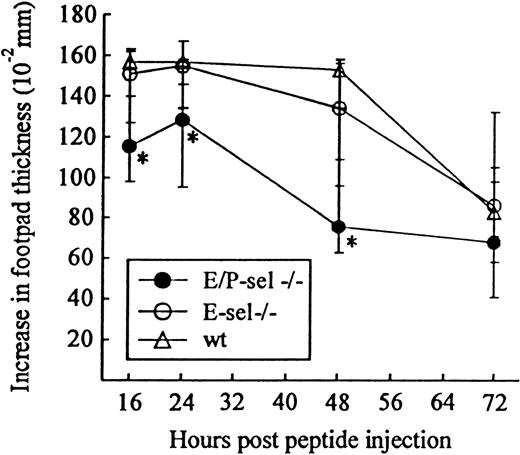

Time course of peptide-induced footpad swelling in infected E/P-sel −/−, E-sel −/−, and wild-type (wt) mice.

Mice were infected iv with 103 LD50 of LCMV and challenged in the right hind footpad with LCMV GP 33-41 (50 μg/mL, 30 μL) on day 8 pi; this peptide represents an immunodominant class I–restricted peptide in H-2b mice. Groups consisted of 4 to 6 mice; medians and ranges are presented. * denotesP < .05 relative to wild-type mice.

Time course of peptide-induced footpad swelling in infected E/P-sel −/−, E-sel −/−, and wild-type (wt) mice.

Mice were infected iv with 103 LD50 of LCMV and challenged in the right hind footpad with LCMV GP 33-41 (50 μg/mL, 30 μL) on day 8 pi; this peptide represents an immunodominant class I–restricted peptide in H-2b mice. Groups consisted of 4 to 6 mice; medians and ranges are presented. * denotesP < .05 relative to wild-type mice.

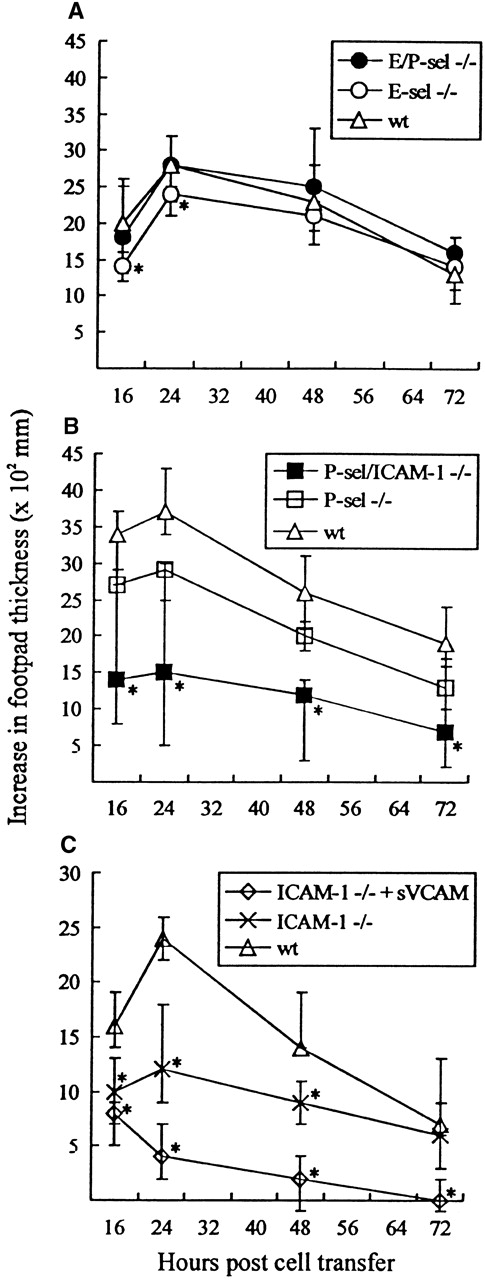

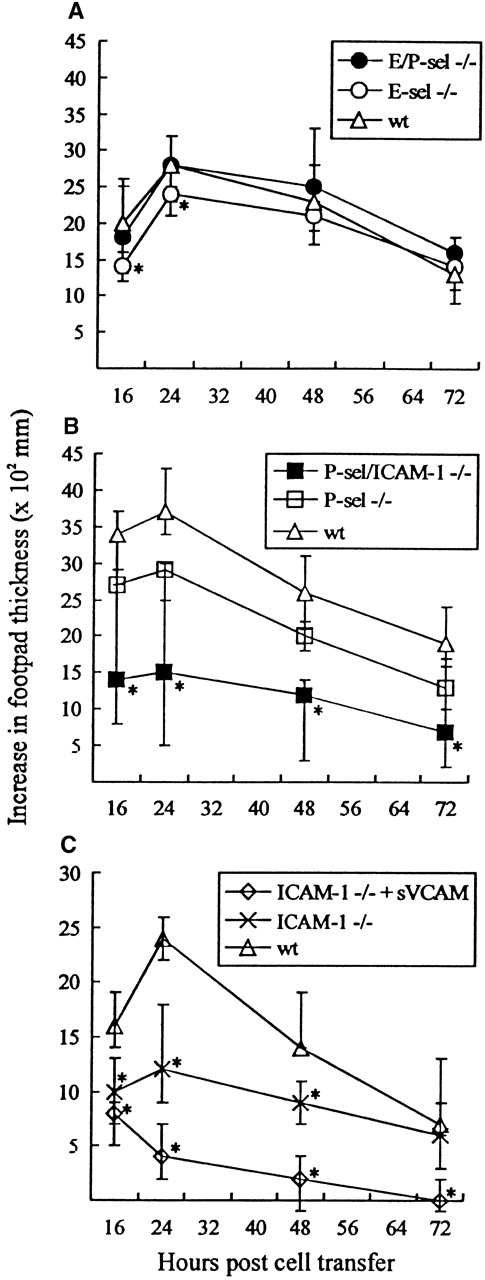

A criticism often raised against the use of gene-targeted mice is that functional redundancy not relevant in wild-type mice may conceal the true importance of the targeted molecule. To minimize the risk that this argument might be valid in the case of selectin knockout mice, adoptive transfer experiments, using infected wild-type mice as cell donors and selectin-deficient mice as recipients, were performed. Mice were challenged with 103 LD50 in the right hind footpad and subsequently transplanted 4 hours later with primed lymphocytes from wild-type donor mice infected iv 8 days previously with the same dose of virus. Footpad swelling was measured for the next 3 days; previous results have clearly established that this response is dependent on transfer of virus-specific CD8+ T cells.38 49 As seen from Figure6A, significant footpad swelling was induced in all recipients, and no major difference in the swelling reaction was observed between mutant and wild-type recipients, although in some experiments marginal reductions in the initial responses of especially E-sel −/− recipients were noted. These findings further suggest that virus-induced lymphocyte homing to infected areas can proceed without local expression of selectins. For comparison, the same reaction was also followed in recipients deficient of P-selectin (P-sel −/−) alone and of P-selectin together with ICAM-1 (P-sel/ICAM-1 −/−). A significantly reduced footpad swelling reaction was observed in P-sel/ICAM-1 −/− mice when compared with wild-type recipients. In contrast, little if any reduction was observed using P-sel −/− recipients (Figure 6B). Together, this indicates a dominant role for endothelial ligands of the Ig superfamily in the formation of this inflammatory response. To confirm this view, additional experiments were carried out in which the primed donor cells preincubated with soluble VCAM-1-Ig chimeric protein. Under these conditions, footpad swelling in ICAM-1 −/− recipients was virtually absent (Figure 6C).

Time course of adoptively transferred virus-specific footpad swelling.

(A) In E/P-sel −/−, E-sel −/−, and wild-type (wt) recipients. (B) In P-sel/ICAM-1 −/−, P-sel −/−, and wild-type recipients. (C) In ICAM-1 −/− mice given donor cells preincubated with soluble VCAM-1-Ig chimeric protein (sVCAM) or human Ig for control. Mice were inoculated in their right footpad with 103 LD50of LCMV. Four hours later they were injected with 5 × 107adherent cell-depleted splenocytes from wild-type donors, infected 8 days earlier with the same dose of virus iv. Groups consisted of 4 to 6 mice; medians and ranges are presented. * denotesP < .05 relative to wild-type mice.

Time course of adoptively transferred virus-specific footpad swelling.

(A) In E/P-sel −/−, E-sel −/−, and wild-type (wt) recipients. (B) In P-sel/ICAM-1 −/−, P-sel −/−, and wild-type recipients. (C) In ICAM-1 −/− mice given donor cells preincubated with soluble VCAM-1-Ig chimeric protein (sVCAM) or human Ig for control. Mice were inoculated in their right footpad with 103 LD50of LCMV. Four hours later they were injected with 5 × 107adherent cell-depleted splenocytes from wild-type donors, infected 8 days earlier with the same dose of virus iv. Groups consisted of 4 to 6 mice; medians and ranges are presented. * denotesP < .05 relative to wild-type mice.

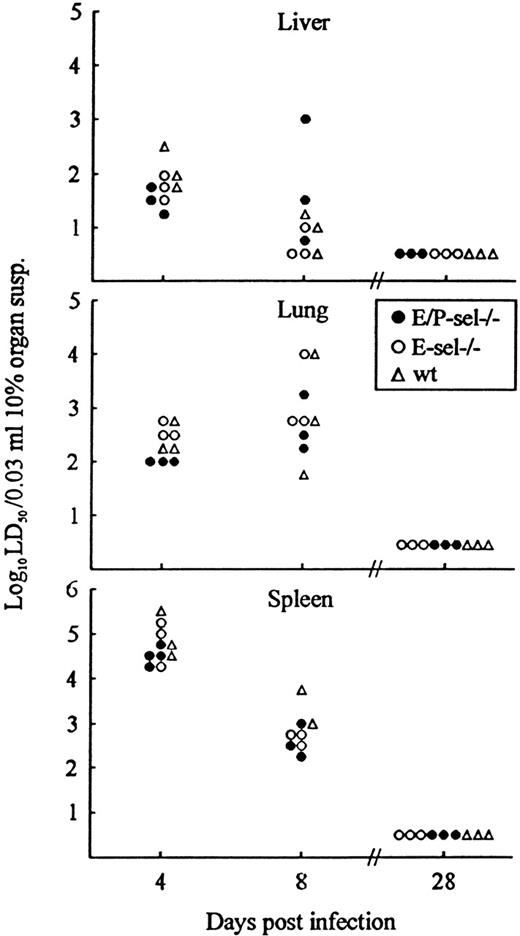

Virus clearance in nonlymphoid organs is independent of E- and P-selectin expression

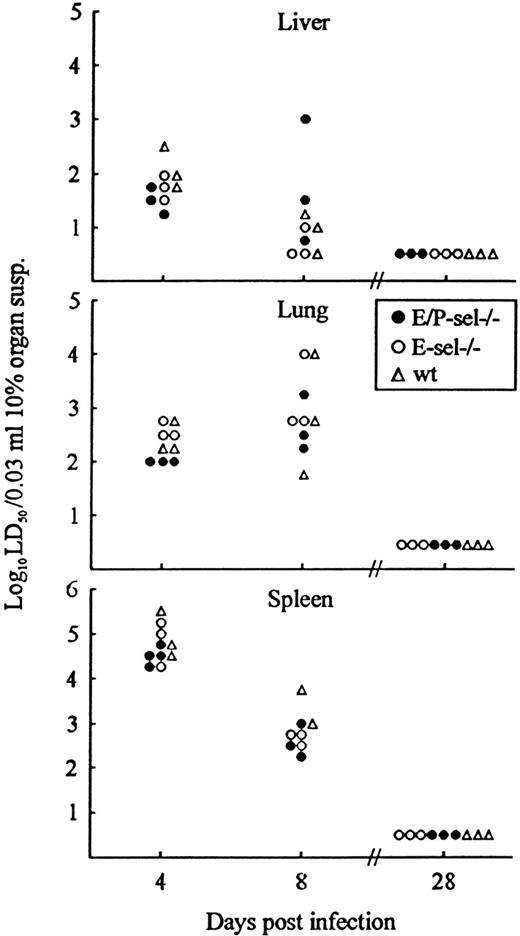

As a final experiment, lymphocyte recruitment in the absence of endothelial selectin expression was indirectly analyzed by evaluating the kinetics of virus clearance in nonlymphoid organs (liver and lungs). Virus clearance in infected organs is a relevant measure of the capacity of CD8+ T cells to extravasate and exert their function locally.39 40 Because identical cytotoxic T-cell responses in mutant mice and wild-type controls have been documented above (Figure 1), a direct comparison between the capacity to clear virus from liver and lungs is valid. Mice were infected with 103 LD50 iv and, on the indicated days, 3 to 4 mice per group were killed, and organs (spleen, liver, and lungs) were removed and assayed for virus content (Figure7). Virus content in the spleen was used as an internal control indicative of T-cell effector capacity in the mice. Compared with wild-type mice, similar levels of virus was found in organs from E-sel −/− mice and E/P-sel −/− mice both before, during, and after the peak of the effector CD8+ T-cell response (∼day 8 pi). This pattern further suggests that effector T-cell migration to infected sites can proceed in the absence of local selectin expression and that, if there is a minor delay under these conditions, it is of marginal biologic relevance.

Organ virus titers in E/P-sel −/−, E-sel −/−, and wild-type (wt) mice infected iv with 103LD50 of LCMV Traub.

Organs (splen, liver, and lungs) were harvested on the indicated days relative to virus inoculation and virus titers were determined. Points represent individual mice.

Organ virus titers in E/P-sel −/−, E-sel −/−, and wild-type (wt) mice infected iv with 103LD50 of LCMV Traub.

Organs (splen, liver, and lungs) were harvested on the indicated days relative to virus inoculation and virus titers were determined. Points represent individual mice.

Discussion

Selectins are generally assumed to play an essential role in the recruitment of leukocytes to inflamed tissue by mediating the initial tethering and rolling required before firm adhesion can be established.1 Several studies that use monoclonal antibody against selectins, as well as studies from knockout mice, have evidenced the general importance of these molecules in inflammatory reactions (recently reviewed in 2). Moreover, recent evidence indicates that endothelial selectins (E- and P-selectin) are needed for CD4+ T cells to migrate into inflamed skin.18 19 However, no studies have previously systematically addressed the role of these selectins in the migration of CD8+ effector T cells, which are central to clearance of many viral infections. Consequently, the current study was undertaken to investigate the requirement for local expression of selectins in extravasation of TC1 cells at sites of viral infection.

As our primary experimental model, we used LCMV-induced meningitis, which is the direct result of antiviral TC1–mediated inflammation of the meninges and ependyma in ic-infected mice.26,29,30,51 Additionally, localized subdermal inflammation (footpad swelling), as well as virus clearance in internal organs, was analyzed; both these reaction types are known also to be critically dependent on the recruitment of TC1 cells.26,39,40,43 On the basis of previous observations concerning TH1 cells,18,19 we had expected E- and P-selectins to be important for extravasation and the subsequent biologic effects of LCMV-specific TC1 cells. However, careful quantitative and qualitative analyses of the inflammatory cells present in CSF of ic-infected mice failed to reveal any significant differences between knockouts and wild-type mice. Therefore, our results strongly indicate that migration of TC1 cells to the infected meninges do not require local expression of endothelial selectins, and that other molecules must suffice in mediating the initial contact between CD8+ effector T cell and local endothelium, at least in this organ site. These findings are in variance with studies of cytokine-induced meningitis, in which it was demonstrated that the development of meningitis is inhibited in E/P-sel −/− mice.24 However, differences in the involved cytokines and/or the composition of the inflammatory exudate may be the cause of this difference. Expression of endothelial selectins was additionally found to be redundant regarding the ability of effector cells to eliminate virus in nonlymphoid organs. Virus clearance in infected organs is an direct measure of the capacity of TC1 cells to function in situ,26,42 and the fact that we do not see any substantial delay in this parameter (day 8 pi values represent virus levels found at the steep slope of the virus elimination curve42) in selectin double knockout mice, further support the suggestion that TC1 cells can be recruited to sites of infection in the absence of selectin-mediated rolling.

Using another model of LCMV-induced T-cell–mediated inflammation, virus-induced footpad swelling, we found that this subdermally induced inflammatory reaction was at most slightly impaired in E/P-sel −/− mice compared with wild-type mice. Similar results were obtained in LCMV-immune mice (mice primed 2 months earlier), demonstrating that redundancy of endothelial selectins could not be explained simply by the high numbers of effector cells or their activation state (effector vs memory cells). After adoptive transfer of wild-type effector cells into E/P-sel −/− recipients, the difference in the magnitude of footpad swelling was marginal or absent. Since it is our general experience that the adoptive approach is a very sensitive method of establishing the functional importance of a given adhesion molecule,34 the latter finding strongly indicates that endothelial selectins play, at most, a marginal role in the extravasation of TC1 cells. The adoptive transfer experiments using primed wild-type donor cells should also partially counter the objection, that leukocytes in mutant mice could have adapted alternative ways to migrate to infected sites. In contrast to the intact responsiveness of E- and P-selectin–deficient mice, markedly impaired footpad swelling was observed in recipients deficient in expression of ICAM-1. Furthermore, the DTH response in the latter mice was completely inhibited by preincubation of the donor cells with soluble VCAM-1-Ig chimeric protein. Thus, in contrast to lack of endothelial selectins, preventing interactions with ligands of the Ig superfamily may completely inhibit the DTH response. This clearly confirms a pivotal role for endothelial ligands of the Ig superfamily,36 and may be taken to support recent findings suggesting that ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 may serve an auxiliary function in leukocyte rolling.52-55 Previous immunohistochemical analysis has clearly demonstrated the up-regulation of these molecules on the endothelium.29 35

In other experimental models, eg, oxalone-induced DTH, absence of E- and P-selectin expression has been found to markedly inhibit the subdermal inflammatory response,22 and homing of TH1 cells to inflamed skin has recently been found to be critically dependent on expression of these selectins.18-20Given that we have also investigated the capacity of E/P-sel −/− mice to support inflammation in this localization, our findings indicate that TH1 and TC1 differ in their requirements for extravasation at sites of subdermal inflammation. More important, using the present model system, we demonstrate that clinically relevant parameters such as virus elimination and susceptibility to ic infection as well as the formation, magnitude, and composition of an inflammatory exudate in the CNS during a viral infection is unaffected by deficiency of endothelial selectins. Additionally, our results suggest that other adhesion molecules suffice for rolling of TC1 cells. As the level of L-selectin expression is down-regulated to a similar degree on activated CD8+ T cells in LCMV-infected E/P-sel −/− mice (data not shown), L-selectin would not appear to be the most obvious candidate. In contrast, α4 integrin is likely to play a role.52 53

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Grethe Thørner Andersen and Lone Malte for expert technical assistance. Daniel Bullard is gratefully acknowlged for providing us with breeder pairs of E- and E/P-selectin knockout mice and Linda Burkly for providing soluble VCAM-1-Ig chimeric protein.

Supported by the Danish Medical Research Council, The Biotechnology Center for Cellular Communication, the Foundation for Advancement of Medical Science, and the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

Reprints:Allan Randrup Thomsen, Institute of Medical Microbiology and Immunology, Panum Institute, 3C Blegdamsvej, DK-2200 N, Copenhagen, Denmark.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.