Abstract

The nucleoside analogue, pentostatin, has demonstrated high complete response rates and long relapse-free survival times in patients with hairy cell leukemia, a disease that historically had been unresponsive to treatment. Long-term data on duration of overall survival and relapse-free survival and incidence of subsequent malignancies with this agent are lacking. Patients completing the treatment phase of a randomized, intergroup study who received pentostatin as an initial treatment or who crossed over after failure of interferon alpha were followed for survival, relapse, and diagnosis of subsequent malignancies. Two hundred forty-one patients treated with pentostatin as initial therapy (n = 154) or who crossed over after failure of interferon alpha (n = 87) were followed for a median duration of 9.3 years. Estimated 5- and 10-year survival rates (95% confidence interval) for all patients combined were 90% (87%-94%) and 81% (75%-86%), respectively. In the 173 patients with a confirmed complete response to pentostatin treatment, 5- and 10-year relapse-free survival rates were 85% (80%-91%) and 67% (58%-76%), respectively. Survival curves for patients initially treated with pentostatin and those crossed over were similar. Only 2 of 40 deaths were attributed to hairy cell leukemia. The mortality rate and incidence of subsequent malignancies were not higher than expected in the general population. Pentostatin is a highly effective regimen for hairy cell leukemia that produces durable complete responses. Subsequent malignancies do not appear to be increased with pentostatin treatment.

Introduction

Hairy cell leukemia is a rare, chronic B-cell malignancy characteristically unresponsive to traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy. Historically, hairy cell leukemia had been managed by splenectomy, but remissions generally were short-lived. In the last decade, the natural history of hairy cell leukemia has been significantly altered by the discovery of several highly effective treatments. Interferon alpha produces high overall objective response rates but the majority are partial responses.1,2 In contrast, 2 purine analogues, pentostatin (deoxycoformycin) and cladribine (2-chlorodeoxyadenosine), have recently been shown to be active in hairy cell leukemia, with complete response rates greater than 75% documented in small noncomparative trials.3-9Several long-term studies with cladribine demonstrate that these remissions are durable, with 3- to 5-year relapse-free survival rates of approximately 80%.6,8,10 11

There are little long-term data with pentostatin.12,13 Because of the promising data shown with pentostatin in early studies, an intergroup study organized by the National Cancer Institute was initiated in 1986 to compare the efficacy and safety of pentostatin and interferon alpha as an initial therapy of hairy cell leukemia in unsplenectomized patients. In this randomized, controlled trial, which enrolled patients between December 1986 and September 1989, patients who did not respond to initial treatment were crossed over so that they could potentially benefit from the other treatment arm of the study. The initial report of this study showed significantly higher complete response rates with pentostatin compared with interferon alpha (76% vs 11%;P < .0001).14 With a median follow-up duration of 57 months, remissions with pentostatin appeared to be durable: 10 of 117 patients responding to pentostatin treatment relapsed compared with 12 of 17 patients responding to interferon alpha (P < .0001).

With a median follow-up duration of 9.3 years, we now report the long-term survival results of patients treated with pentostatin on this study. In view of the concern of a potentially higher risk of secondary neoplasms in patients with hairy cell leukemia,15 16 the incidence of secondary malignancies was also evaluated in this study.

Patients and methods

Patients and treatment

Patients were participants in an intergroup phase 3 study comparing interferon alpha-2a with pentostatin conducted by the Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG), Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB), and National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group (NCIC CTG). Patients entered into the randomized study were adults (18 years or older) previously untreated with cytotoxic agents or interferon. Patients were required to have hairy cell leukemia confirmed by bone marrow biopsy, to not have had a splenectomy, and to have active disease documented by one or more of the following: hemoglobin less than or equal to 12 g/dL, absolute granulocyte count less than or equal to 1 500/μL, or platelet count less than or equal to 100 000/μL; recurrent infections requiring antibiotics; symptomatic splenomegaly; and circulating hairy cell count more than or equal to 20 000/μL. Patients also were to have adequate renal, hepatic, and cardiac function, and performance status less than or equal to 3 at the start of the study. Patients were not excluded on the basis of an active infection.

Patients were randomized to initial treatment with interferon alpha-2a or pentostatin for 6 months. Patients randomized to interferon alpha-2a received a self-administered study drug at a dose of 3 × 106 units subcutaneously 3 times per week. Treatment was continued for 6 months (or less if evidence of progressive disease). Patients with an objective partial response were treated for an additional 6 months or until complete response or disease progression. Patients with progressive disease or stable disease and those who had experienced toxicity with interferon alpha-2a not responsive to dose reduction were crossed over to pentostatin.

Patients randomized to pentostatin received a study drug in an outpatient setting at a dose of 4 mg/m2 every 2 weeks by rapid intravenous injection. (The initial pentostatin dose could be reduced based on performance status and subsequent doses could be reduced based on renal function).8 Patients who achieved a complete response before 6 months received 2 additional doses of pentostatin 14 days apart and treatment was then stopped. Patients with an objective partial response were treated for a further 6 months or until complete response or disease progression. Patients with progressive disease or stable disease and those who had experienced toxicity with pentostatin not responsive to dose reduction were crossed over to interferon alpha-2a.

Patients whose hairy cell leukemia relapsed or progressed less than 3 months after discontinuing the initial therapy were crossed over to the alternative therapy. If relapse occurred more than 3 months after discontinuing the initial therapy, patients were retreated with the same therapy.

Follow-up assessments

Patients were assessed monthly during the first 2 years, at 3-month intervals for the next 3 years, and yearly thereafter. Patients who had achieved a complete response (as indicated by absence of disease-related symptoms and confirmed by bone marrow biopsy and aspirate and physical examination) lasting 28 days or more with initial pentostatin therapy or after crossover from interferon alpha-2a to pentostatin therapy were followed for relapse and survival. Relapse was defined as the reappearance of evidence of hairy cell leukemia in peripheral blood and bone marrow samples in a patient who previously achieved a complete response. All bone marrow aspirates and biopsy specimens were reviewed centrally by the hematopathologists of each cooperative group.

This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards set forth by the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 1983, and with the individual Institutional Review Boards that approved this study. All patients gave signed informed consent before participation.

Statistical analyses

The objectives of the follow-up phase of this study were to evaluate long-term survival, relapse-free survival, and incidence of subsequent malignancies in patients who received pentostatin as initial or crossover therapy in the randomized phase of the study. All patients were evaluated for survival. Survival was measured from the day of registration for pentostatin therapy until death from any cause (observations were censored for patients last known to be alive). Relapse-free survival was defined as the time interval between the date that complete response was established until first relapse or death from any cause. Observations of relapse-free survival were censored at the date of last contact for patients with no report of relapse who were last known to be alive. Distributions of relapse-free survival and overall survival were estimated by the method of Kaplan and Meier and compared between subgroups using the log rank test.17 18

Mortality and cancer incidence after registration for pentostatin therapy were compared with those of the general US population using standardized mortality and incidence ratios (SMRs and SIRs, respectively).19 Expected numbers of deaths were calculated from 1990 age- and sex-specific mortality rates for white patients reported by the National Center for Health Statistics.26 Corresponding cancer incidence rates for 1989-1993 were obtained from the US National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program.20

Results presented here are based on data available as of April 16, 1999.

Results

Patients

One hundred fifty-four eligible patients were randomized to initial pentostatin treatment at study entry. Of the 159 eligible patients randomized to initial interferon alpha-2a treatment, 87 patients failed treatment (84 because lack of response, 3 because toxicity) and were eligible for and crossed over to pentostatin (median time after randomization, 7 months; range, 2-64 months). Thus, a total of 241 patients were evaluable for long-term follow-up with pentostatin. Patients were primarily male, white, and had good performance status. Patients initially randomized to pentostatin and those crossed over from interferon alpha treatment were generally similar in pretreatment demographic and clinical characteristics (Table1).

Overall survival

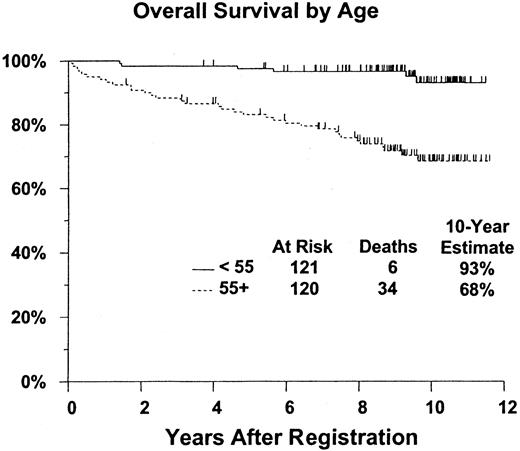

Of the 241 eligible patients, 40 have died (28 initially treated with pentostatin and 12 cross-overs). For the remaining 201 patients, median duration of follow-up is 9.3 years (range, 19 months-11.6 years, with only 6 having less than 4 years of follow-up). Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival (Table 2) were 90% (95% confidence interval [CI], 87%-94%) at 5 years and 81% (CI, 75%-86%) 10 years after initiation of treatment. Survival outcomes were similar for patients initially treated with pentostatin and those crossed over from interferon alpha-2a treatment (2-tailed log rankP = .59) (Figure 1).

Survival does not differ significantly between patients receiving pentostatin as initial induction, compared with those crossed over from interferon therapy.

P = .59. Figure shows estimated distributions of overall survival (Kaplan-Meier estimates) from date of registration for pentostatin therapy, by phase of treatment. Tick marks indicate patients who were alive at last contact.

Survival does not differ significantly between patients receiving pentostatin as initial induction, compared with those crossed over from interferon therapy.

P = .59. Figure shows estimated distributions of overall survival (Kaplan-Meier estimates) from date of registration for pentostatin therapy, by phase of treatment. Tick marks indicate patients who were alive at last contact.

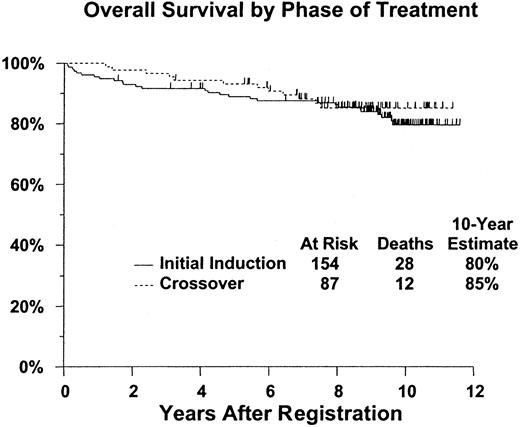

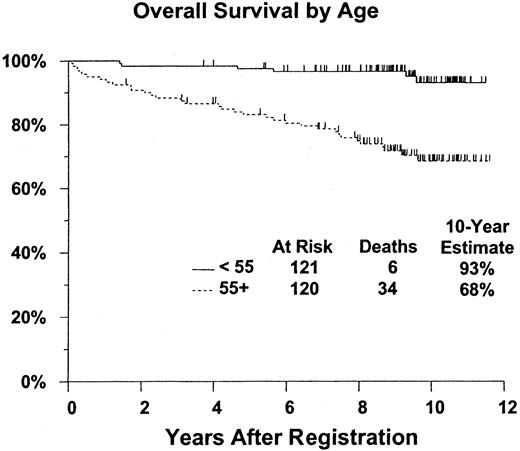

Overall survival was also evaluated according to patient age group (younger than 55 years of age [n = 121] vs 55 years of age or older [n = 120]). Ten-year survival rate was 93% (CI, 87%-99%) for patients younger than 55 years of age compared with 68% (CI, 59%-78%) for patients 55 years of age and older (Figure2). This difference was statistically significant in favor of the younger-age patients (2-tailed log rankP < .0001).

Survival is significantly better for patients younger than age 55. P < .0001. Figure shows estimated distributions of overall survival (Kaplan-Meier estimates) from date of registration for pentostatin therapy, by age at start of initial therapy. Tick marks indicate patients who were alive at last contact.

Survival is significantly better for patients younger than age 55. P < .0001. Figure shows estimated distributions of overall survival (Kaplan-Meier estimates) from date of registration for pentostatin therapy, by age at start of initial therapy. Tick marks indicate patients who were alive at last contact.

A total of 40 patients died, 7 within 1 year after registration for pentostatin treatment and 33 after 1 year. The reasons for death are summarized in Table 3. Of the 40 patients who died, only 2 deaths were attributed to hairy cell leukemia. (Both patients had crossed over to pentostatin after failure of interferon alpha-2a treatment. One patient achieved a complete remission with pentostatin, which was maintained for 32 months. The other patient was noncompliant with follow-up studies and was withdrawn from treatment.) To evaluate the mortality experience of the study patients, an SMR was calculated and compared with that of the general population. On the basis of the 1990 age- and sex-specific mortality rates for the white population in the United States,20 the expected number of deaths among these 241 patients is 38.0. With 40 deaths observed, the SMR for the study cohort is 1.05 (CI, 0.75-1.43).

Relapse-free survival

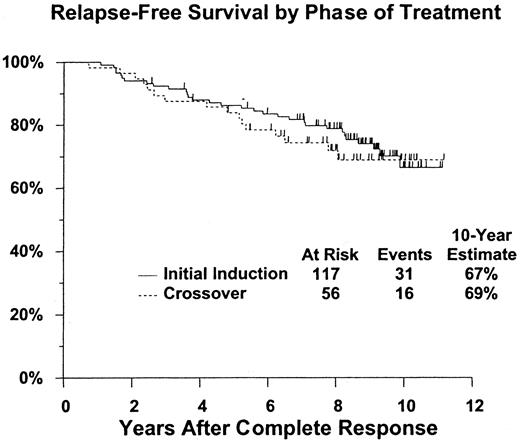

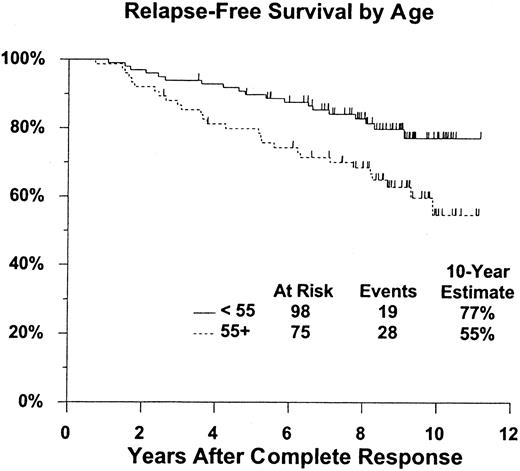

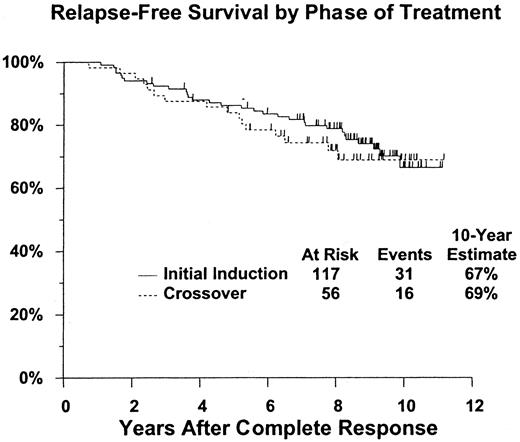

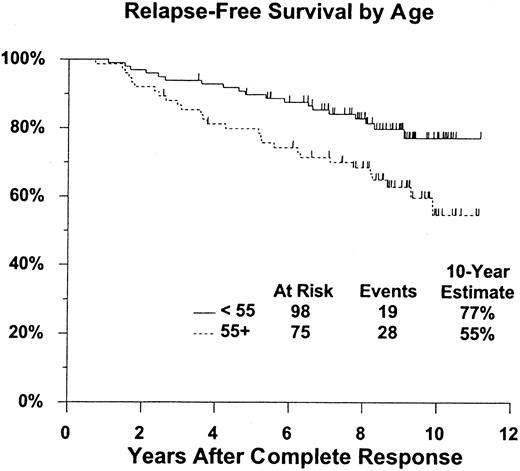

The analysis of relapse-free survival is based on 173 patients who achieved a confirmed complete response (117 after initial treatment with pentostatin and 56 who crossed over from interferon alpha-2a to pentostatin treatment). A total of 32 patients have relapsed (20 initial pentostatin, 12 crossed over), 4 of whom have died (3 initial pentostatin, 1 crossed over); 15 additional patients have died without documented relapse (11 initial pentostatin, 4 crossed over). Estimated 5- and 10-year relapse-free survival rates are 85% (CI, 80%-91%) and 67% (CI, 58%-76%), respectively, with similar outcomes regardless of initial treatment (2-tailed log rank P = .57) (Table 2, Figure 3). Relapse-free survival was also evaluated according to patient age group (younger than 55 years of age [n = 98] vs 55 years of age or older [n = 75]). The 10-year relapse-free survival rate was 77% (CI, 68%-87%) for patients younger than 55 years of age compared with 55% (CI, 40%-70%) for patients 55 years of age and older (Figure4). This difference was statistically significant (2-tailed log rank P = .012).

Relapse-free survival does not differ significantly between those receiving pentostatin as initial induction, compared with those crossed over from interferon therapy (

P = .57). Figure shows estimated distributions of relapse-free survival (Kaplan-Meier estimates) from date of complete response, by phase of treatment. Tick marks indicate patients who were alive without report of relapse at last contact.

Relapse-free survival does not differ significantly between those receiving pentostatin as initial induction, compared with those crossed over from interferon therapy (

P = .57). Figure shows estimated distributions of relapse-free survival (Kaplan-Meier estimates) from date of complete response, by phase of treatment. Tick marks indicate patients who were alive without report of relapse at last contact.

Relapse-free survival is significantly better for patients younger than age 55.

P = .012. Figure shows estimated distributions of relapse-free survival (Kaplan-Meier estimates) from date of complete response, by age at start of initial therapy. Tick marks indicate patients who were alive without report of relapse at last contact.

Relapse-free survival is significantly better for patients younger than age 55.

P = .012. Figure shows estimated distributions of relapse-free survival (Kaplan-Meier estimates) from date of complete response, by age at start of initial therapy. Tick marks indicate patients who were alive without report of relapse at last contact.

Subsequent malignancies

Thirty-nine of the 241 eligible patients had documented subsequent malignancies (Table 4). A total of 33 malignancies other than basal/squamous cell skin cancers were reported in 31 patients (23 men), with a median age at first subsequent diagnosis of 66 years (range, 32-84 years) and a median of 3.8 years between the start of pentostatin treatment and diagnosis of malignancy (range, 12 days-9.4 years). Thirteen (42%) of these 31 patients had been crossed over from interferon (IFN) to pentostatin, a somewhat higher proportion than among the remaining patients (74 of 210 patients, or 35%). This increase was attributable to the 8 patients whose subsequent malignancies were hematologic, 5 (63%) of whom had prior IFN (leaving 8 of 23, or 35%, among the patients with solid tumors). The responses of 6 of the 31 patients to pentostatin therapy were unknown: Three were removed from pentostatin treatment because of their subsequent diagnoses, and the assessments of 3 others were inadequate to determine response. Of the remaining 25 patients, 17 (including 15 with solid tumors) had subsequent malignancies diagnosed while their hairy cell leukemia (HCL) was in continuous complete remission from their first pentostatin therapy. Two other malignancies (including one solid tumor) were diagnosed during complete remissions, induced by retreatment with pentostatin on study, in patients whose first pentostatin-induced remissions had ended in relapse. One patient's subsequent malignancy was diagnosed while his hairy cell leukemia was in a partial response that eventually converted to complete remission. The remaining 5 patients' diagnoses occurred after disease progression or failure to achieve complete remission; information on further therapy for HCL in these patients is not available. On the basis of sex- and age-specific incidence rates during 1989-1993 for white patients, as reported by the US SEER registries,20 the expected total number of diagnoses of invasive cancer in this group of patients is 26.3, giving an SIR of 1.26 (95% CI, 0.86-1.77).

Because of uncertainty about whether subsequent diagnoses of lymphoma, myeloma, or leukemia might actually be misdiagnoses of hairy cell leukemia, the expected numbers of total diagnoses (all invasive malignancies) of solid tumors were calculated. When lymphoid and hematologic malignancies were excluded, there were 25 cases of solid tumors diagnosed in 23 patients occurring at a median of 4.1 years after initiation of treatment (range, 12 days-9.4 years). The expected number of diagnoses of solid, invasive tumors is 24.4, giving an SIR of 1.02 (95% CI, 0.66-1.52). Thus, the incidence of overall second malignancies and of solid tumors was not increased among patients treated with pentostatin in this study.

Discussion

With a median follow-up duration of 9.3 years after initiation of treatment, this study provides the longest duration of follow-up information in patients treated for hairy cell leukemia. Median overall and relapse-free survival in this population of previously untreated, unsplenectomized patients treated with pentostatin has not yet been reached. Estimated 5- and 10-year overall survival rates of 90% and 81%, respectively, represent a significant prolongation of life in a disease that remained unresponsive to therapy before the introduction of purine nucleoside analogues.21 Other long-term data currently available with pentostatin (median follow-up times of 38-82 months) in hairy cell leukemia show similar long survivals, although in studies with small numbers of patients (n ≤ 50).12,13Because the younger age was previously shown to be a significant favorable prognostic factor for complete remission rate,14we also analyzed long-term overall and relapse-free survival in pentostatin-treated patients classified by age group. In this study, there also appears to be a more favorable outcome for younger patients (ie, younger than 55 years of age).

Remarkably, the mortality experience of the patients in this study did not differ significantly from that predicted for the general population. However, this should not be interpreted as conclusive evidence that hairy cell leukemia has no impact on life expectancy. There may be unknown factors in the selection of patients for this study that introduce bias into their comparison with the general population. In fact, mortality was greater in patients with hairy cell leukemia than in the general population in a retrospective analysis of 350 patients, primarily because of disease-related infections and secondary malignancies.22 However, it should be noted that only 2 patients in the current study subsequently died from hairy cell leukemia.

The number of diagnoses of all invasive malignancies and of solid tumors are also consistent with predicted numbers and the SIRs for these events are not significantly greater than 1.0. This is true even though the numbers of reported malignancies may be somewhat inflated by cases of lymphoma, myeloma, or leukemia that might actually be misdiagnoses of hairy cell leukemia. In addition, 3 of 31 patients with subsequent malignancies other than basal/squamous cell skin cancers were diagnosed within 135 days after registration for pentostatin therapy, including one patient who had colon cancer diagnosed 28 days after registration. However, the inclusion of all subsequent diagnoses is conservative (ie, probably inflates the SIRs). Because the SIRs were not significantly greater than 1.0, these data are consistent with the report of no apparent increased incidence of secondary malignancies in other studies of patients with hairy cell leukemia treated with pentostatin.12,13,22 23

Pentostatin is a purine analogue that inhibits the catabolic enzyme, adenosine deaminase, which is responsible for conversion of adenosine to inosine. The exact mechanism by which pentostatin exerts its cytotoxic effects, however, is uncertain, but may include intracellular dATP accumulation, depletion of deoxynucleotides and inhibition of DNA synthesis, depletion of ATP, inhibition of RNA transcription, and other cellular reactions. Long-term studies with cladribine, an adenosine deaminase-resistant purine analogue, also produced long-term remissions.5,7,10,11,24,25 However, direct comparisons of the current results with those produced by cladrabine are difficult, given the differences in the designs of trials with the 2 agents. These studies of cladrabine are either small (approximately 50 patients in each) or have a significantly shorter median follow-up than the 9.3-year median follow-up duration in this study. However, the estimated probability of survival results at 48 months in this trial for the pentostatin patients in this study (93%, 95% CI, 89%-96%) is similar to what has been reported in a large, single-center study with cladrabine (96%, 95% CI, 94%-98%).24

This study provides important long-term data on survival and durability of complete responses with pentostatin in hairy cell leukemia. With a median follow-up of 9.3 years, 83% of patients treated with pentostatin are still alive and only 18% of patients who achieved a complete relapse have relapsed. It is possible that some patients with microscopic evidence of marrow relapse have gone undetected, as the methods of minimal residual disease detection have been refined since the design of this protocol. However, such relapses are of uncertain clinical significance. There has been no increase in secondary malignancies seen over this extended follow-up period from that expected in the general population. Pentostatin has had a significant impact on the management of this disease. With the advent of purine nucleosides, the natural history of hairy cell leukemia has clearly been improved. In fact, few people now actually die of hairy cell leukemia after remission induction. Infection and secondary malignancies had been shown in previous studies to be the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in patients with this disease. More importantly, results with pentostatin in hairy cell leukemia emphasize the impact of achieving a high complete remission on changing the natural history of a malignant disease. Although this rare form of leukemia is exquisitely sensitive to a single agent, novel strategies to effect a high complete response rate in other indolent lymphoid malignancies hopefully will achieve similar success.

Acknowledgment

We express our appreciation to Linda Mattucci Schiavone, MSc, for editorial assistance.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants CA38926, CA20319, CA04920, CA46441, CA35117, CA12644, CA58686, CA22433, CA04919, CA20319, CA45377, CA35176, CA46136, CA45200, CA46368, CA35261, CA46113, CA35128, CA35431, CA42777, CA35090, CA12213, CA35192, CA35178, CA35262, CA32734, CA58658, CA46282, CA27057, CA16385, CA13612, CA37981, CA32102, CA11083, CA15488, CA13650, CA21060, CA41287, and CA11028. Financial support for data analysis was provided by Supergen, Inc, San Ramon, CA.

M.R.G. has declared a financial interest in a company whose product was studied in the present work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG-8691), Operations Office, 14980 Omicron Dr, San Antonio, TX 78245-3217.