Abstract

Syndecan-1 is a heparan sulfate proteoglycan expressed on the surface of, and actively shed by, myeloma cells. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) is a cytokine produced by myeloma cells. Previous studies have demonstrated elevated levels of syndecan-1 and HGF in the serum of patients with myeloma, both of negative prognostic value for the disease. Here we show that the median concentrations of syndecan-1 (900 ng/mL) and HGF (6 ng/mL) in the marrow compartment of patients with myeloma are highly elevated compared with healthy controls and controls with other diseases. We show that syndecan-1 isolated from the marrow of patients with myeloma seems to exist in an intact form, with glucosaminoglycan chains. Because HGF is a heparan-sulfate binding cytokine, we examined whether it interacted with soluble syndecan-1. In supernatants from myeloma cells in culture as well as in pleural effusions from patients with myeloma, HGF existed in a complex with soluble syndecan-1. Washing myeloma cells with purified soluble syndecan-1 could effectively displace HGF from the cell surface, suggesting that soluble syndecan-1 can act as a carrier for HGF in vivo. Finally, using a sensitive HGF bioassay (interleukin-11 production from the osteosarcoma cell line Saos-2) and intact syndecan-1 isolated from the U-266 myeloma cell line, we found that the presence of high concentrations of syndecan-1 (more than 3 μg/mL) inhibited the HGF effect, whereas lower concentrations potentiated it. HGF is only one of several heparin-binding cytokines associated with myeloma. These data indicate that soluble syndecan-1 may participate in the pathology of myeloma by modulating cytokine activity within the bone marrow.

Introduction

Heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) are important regulators of cell development and behavior. They are expressed both on cell surfaces and in the extracellular matrix. Through their heparan sulfate side chains, HSPGs have the ability to bind numerous growth factors.1 Syndecan-1, the most abundant HSPG on myeloma cells,2,3 consists of a transmembrane core protein and both heparan sulfate and condroitin sulfate glucosaminoglycan (GAG) side chains. Interestingly, the entire ectodomain of syndecan-1 can be actively shed from myeloma cells in vivo as well as in vitro,4 5 resulting in a soluble form of syndecan-1.

Syndecan-1 may affect growth factor activity in several ways. Membrane-bound syndecan-1 mediates cell attachment to extracellular matrix,3,6,7 and may facilitate the binding of growth factors to their high-affinity receptors, as shown for basic fibroblast growth factor (b-FGF).8 It is possible that soluble syndecan-1 may mobilize cytokines in a manner similar to that of heparin, which releases hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) from its low-affinity heparan sulfate binding sites in extracellular matrix and on cell surfaces.9-12 Alternatively, soluble syndecan-1 could modulate the interaction between heparan-sulfate binding cytokines and their high-affinity cell-surface receptors.

Soluble syndecan-1 has been shown to induce apoptosis of myeloma cells and inhibit osteoclastogenesis in vitro,4,5,13 both potentially favorable effects for the patient. However, we have recently reported that elevated levels of syndecan-1 in serum is a strong and independent negative prognostic factor for patients with myeloma,14 suggesting that shed syndecan-1 could have harmful effects in vivo. Because multiple myeloma is a disease of the bone marrow, it is of interest to know whether there is soluble syndecan-1 in the bone marrow microenvironment, and whether soluble syndecan-1 can interfere with the activity of cytokines.

HGF is a 90-kd protein synthesized by mesenchymal cells, with activity primarily on epithelial cells in several organs.15 HGF is produced by myeloma cells,16,17 and elevated levels of HGF in the serum of patients with myeloma are associated with a poor prognosis.18 HGF in the bone marrow compartment may play a role in the increased bone resorption of multiple myeloma.19-21 HGF has a heparin-binding domain, and thus binds with low affinity (KD 260 pmol/L) to cell surface HSPGs,15,22 in addition to binding to the specific tyrosine kinase receptor, c-Met (KD 20-25 pmol/L).15,22 23

In this study, we examined the levels of syndecan-1 and HGF present in the bone marrow microenvironment of patients with myeloma. We discovered that HGF produced by the myeloma cells is bound to myeloma-derived syndecan-1, and that soluble syndecan-1 can modulate the biologic activity of HGF in vitro.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patient samples

Thirty-five patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma were included for the analysis of syndecan-1 and HGF in the bone marrow. Before treatment, after informed consent, bone marrow was aspirated from the crista iliaca or sternum. Aspirates were centrifuged and serum or plasma was frozen at −70°C until analysis.

Controls

Two sets of controls were included. Twenty-one patients with other diseases but normal bone marrow morphology, from whom bone marrow plasma or serum had been collected, served as the first set. In addition, 14 healthy volunteers aged 20 to 25 were included. This study was approved by the Norwegian Board of Ethics, health region 4. For all controls, bone marrow was collected and stored in an identical manner to the patients with myeloma.

Detection of syndecan-1 and hepatocyte growth factor by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

A syndecan-1 antibody pair (Diaclone, Besancon, France) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. All samples were run in duplicate. The standard curve was linear between 15 and 256 ng/mL, and samples were diluted to concentrations within this range. Internal standards were included in all analyses, and the interassay and intraassay coefficients of variation were less than 5%. The addition of HGF (1-50 ng/mL) to samples did not interfere with the detection of syndecan-1.

A sandwich HGF enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) developed in our laboratory was performed as described elsewhere.18 The sensitivity of this assay was 0.15 ng/mL HGF. The interassay coefficient of variation was less than 10% from the mean. The addition of syndecan-1 (250 ng/mL-3 μg/mL) to samples did not interfere with the detection of HGF.

Cell lines and cell culture

The human myeloma cell line JJN-324 was a gift from Jennifer Ball, Department of Immunology, University of Birmingham, UK. The RPMI 8226 and U-266 cell lines were purchased at American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD). The ANBL-6 cell line was a kind gift from Diane Jelinek (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN). Syndecan-1–negative ARH-77 cells were transfected with either a control vector carrying the neomycin resistance gene (ARH-77neo) or a full-length murine syndecan-1 construct (ARH-77syn-1), as described elsewhere.7 All these cell lines were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium, supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS); ANBL-6 was also supplemented with 1 ng/mL IL-6. The OH-2 cell line was established in our laboratory,25 and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium, supplemented with 10% human A+ serum and 100 pg/mL IL-6.

Harvesting of myeloma cell medium

Six myeloma cell lines (JJN-3, OH-2, U-266, RPMI 8226 ANBL-6, and ARH-77) were seeded at 1 × 106 cells in 5 mL of medium. Supernatants were collected after 72 hours and analyzed for the presence of shed syndecan-1 by ELISA.

Flow cytometry

For the determination of syndecan-1 expression on the myeloma cell surface, 6 myeloma cell lines (JJN-3, OH-2, U-266, RPMI 8226, ANBL-6, and ARH-77) were seeded at 1 × 106 cells in 5 mL and cultured for 72 hours. The 106 cells from each cell line were labeled with anti–syndecan-1 antibody B-B42(Diaclone) or an irrelevant antibody. After washing, the cells were labeled with with fluorescein isothiocyante (FITC)-conjugated goat antimouse IgG (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA). In a FACSscan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson), 5000 cells from each sample were analyzed on a single cell basis. The relative expression of syndecan-1 on the cell surface was estimated as the mean fluorescence intensity of specific antibody-labeled cells divided by the mean fluorescence intensity of control-labeled cells.

To detect HGF on the cell surface, 2 experiments were performed. First, 1 × 106 JJN-3 cells, that are high producers of HGF, were washed with 1 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or 10 μg/mL heparin in PBS or 10 μg/mL syndecan-1 in PBS. Also, 2 × 106 ARH-77neo and 2 × 106ARH-77syn-1 cells were washed in complete media, resuspended in 100 μL PBS, and incubated with HGF (5 μg/mL) on ice for 30 minutes. To see whether heparan sulfate mediated the binding of HGF, 2 × 106 ARH-77syn-1 cells were also treated with 0.010 units heparitinase (Seikagaku, Tokyo, Japan) 30 minutes at 37°C in complete medium before HGF incubation. After 3 washes with 1 mL PBS, cells were labeled with unconjugated anti-HGF antibody 3F4 (developed in our laboratory16) and subsequently with FITC-conjugated goat antimouse IgG (Becton Dickinson). In a FACSscan flow cytometer, cells were analyzed as described previously and displayed as frequency distribution histograms.

Coprecipitation of syndecan-1 and hepatocyte growth factor

Medium from myeloma cell lines (JJN-3 and ANBL-6), and pleural fluid from 2 patients with myeloma, with extramedullary spread to the pleural cavity, were centrifuged at 10 000g for 10 minutes and supernatants were passed through a 0.45-μm sterile filter. Each sample was divided into 3 aliquots of 5 mL, and 5 μg of monoclonal anti–syndecan-1 antibody B-B4 was added to tubes 1 and 2. Heparin (Leo, Ballerup, Denmark) was added to tube 2 at a concentration of 50 μg/mL, and 5 μg of an irrelevant isotype-matched antibody was added to tube 3. The tubes were placed on a rolling tray for 1 hour. Twenty microliters of goat antimouse sepharose beads (Zymed Laboratories Inc, San Francisco, CA), prewashed in 10% FCS, were added to each tube. The samples were incubated overnight at 4°C. The sepharose beads were pelleted and washed twice with 10 mmol/L Tris/HCl pH 7.4, 0.15 mol/L NaCl and once with 10 mmol/L Tris/HCl pH 7.4. The beads were resuspended in SDS sample buffer, boiled for 2 minutes, centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected.

SDS-polyacrylamide gels were run and blotted onto nitrocellulose filters (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA). The filters were incubated with a polyclonal rabbit anti-HGF antibody developed in our laboratory at a dilution of 1:700, followed by goat antirabbit HRP conjugates and enhanced chemiluminiscence detection (Amersham, Aylesbury, UK). Purified HGF from the myeloma cell line JJN-3 served as a positive control.

Purification of syndecan-1 from culture medium

The cell line with the highest secretion of the soluble ectodomain of syndecan-1 and the highest cell growth rate (U-266) was selected for further production of soluble syndecan-1 for purification, with a procedure modified from Jalkanen et al.26 U-266 cells were cultured in 10% FCS in RPMI. The conditioned medium was brought to 2 mol/L in urea, 50 mmol/L in Na-acetate, pH 4.5. The mixture was clarified by centrifugation at 10 000g for 10 minutes, and then loaded onto a Q-sepharose column, previously equilibrated with this loading buffer, at 2 mL/min. The column was washed with 3 column volumes of the loading buffer and then eluted with a linear 0.2 to 1.0 mol/L NaCl gradient in the same buffer at 2 mL/min. After elution, aliquots from each 8-mL fraction were analyzed by ELISA for syndecan-1–positive material, as described previously. Positive fractions were pooled, and dialyzed at 4°C against PBS.

The monoclonal anti–syndecan-1 antibody B-B4 was bound to a high-trap N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS)-activated sepharose column (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The column was equilibrated with PBS and the dialyzed proteoglycan sample was loaded at 20 mL/h. After washing with 2 column volumes of 0.5 mol/L NaCl and 3 column volumes of PBS, it was eluted with 50 mmol/L triethylamine pH 11 at 1 mL/min to release the bound material. Eluents were immediately neutralized with 1 mol/L Tris/HCl to pH 7.4. Aliquots were analyzed for syndecan-1 by ELISA. Positive samples were pooled, dialyzed against water, lyophilized, and kept frozen at −20°C until use.

Analysis of syndecan-1 purity

Syndecan-1–positive aliquots from each purification step were analyzed on 4% to 15% polyacrylamide gels on a Phast System (Pharmacia). Proteoglycans were detected by combined alcian blue/silver staining, as described by Møller et al.27 Briefly, immediately after electrophoresis, the gel was placed in the development chamber of the Phast system and washed with 25% ethanol, 10% acetic acid in water. The gel was then stained with 0.125% alcian blue in the above buffer for 15 minutes, and washed thoroughly. Subsequently, gels were stained according to a neutral silver staining protocol. As a parallel, gels were stained only by the neutral silver staining protocol.

Purification of syndecan-1 from patient material

To assess the size and to confirm the intactness of syndecan-1 detected in the marrow of patients with myeloma, syndecan-1 was isolated from bone marrow plasma of 3 patients with myeloma. In addition, syndecan-1 was isolated from the 2 pleural fluids mentioned previously. Samples (200-800 μL of marrow depending on availability and 5 mL of each pleural fluid) were diluted 1:1 with 4 mol/L urea and brought to 50 mmol/L Na-acetate, pH 4.5. The mixture was clarified by centrifugation at 10 000g for 10 minutes, and the supernatant was mixed with 100 μL washed DEAE beads (Pharmacia Biotech) per milliliter sample. The mixture was placed on a moving tray for 3 hours. Beads were washed 3 times in PBS and bound material eluted with 2 mol/L NaCl. After centrifugation, the supernatant was diluted to a final salt concentration of 0.2 mol/L NaCl.

For each sample, 5 μg of B-B4 antibody was adhered to 30 μL washed goat antimouse sepharose beads (Zymed Laboratories Inc). After washing, these beads were added to the DEAE eluate, and the mixture left on a moving tray overnight. Beads were spun and washed once in 0.5 mol/L NaCl, twice in PBS. Beads were resuspended in 20 μL of SDS-PAGE buffer and boiled. Samples were analyzed on 4% to 15% polyacrylamide gels stained for GAG chains by the method of Møller et al27 described previously.

Stimulation of IL-11 secretion from Saos-2 cells

Cells from the osteosarcoma cell line Saos-2 were seeded in 24-well plates at 5 × 104 cells per well in RPMI-8226 medium with 10% FCS. After 24 hours, the medium was replaced with 1 mL of fresh medium with 2% FCS and rabbit anti-HGF serum or preserum, as well as varying concentrations of HGF, heparin (Leo, 5000 IU/mL) or syndecan-1.

After 48 hours of culture, the supernatants were collected, centrifuged, and analyzed for IL-11 by ELISA. Samples were analyzed in duplicates by ELISA (RD Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The sensitivity of this assay is approximately 30 pg/mL.

Statistical methods

The SPSSX/PC computer program (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used for all statistical analyses. Correlations between groups were performed by the method of Spearman. Analyses of differences between groups were performed with the Mann-Whitney U test and Student t test. P values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Syndecan-1 and hepatocyte growth factor are present in high levels in the bone marrow of patients with myeloma

As shown in Figure 1A, 54% of patients with myeloma had elevated syndecan-1 levels in the marrow (ie, above mean + 2 SD of healthy controls = 847 ng/mL). The median level of soluble syndecan-1 in the marrow was 900 ng/mL in patients with myeloma (range 100-13 000 ng/mL). This was highly elevated, compared with the controls with other diseases (median 340 ng/mL, range 180-1000 ng/mL), P = .002 and healthy controls (median 300 ng/mL, range 195-1095 ng/mL), P = .001. The difference between the groups was also evident regarding mean values (mean 1771 ng/mL in patients with myeloma, 464 ng/mL in patient controls, and 379 ng/mL in healthy controls P = .007 andP = .004, respectively, Student ttest).

Elevated concentrations of syndecan-1 and HGF in the bone marrow of patients with myeloma.

Serum or plasma from bone marrow aspirates of 35 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM), 21 controls with other diseases, and 14 healthy controls were analyzed by ELISA for syndecan-1 (A). Median levels are indicated by the horizontal bars. The difference between patients with myeloma and patient controls was highly significant (P = .002). The difference between patients with myeloma and healthy controls was highly significant (P = .001). (B) HGF. Median levels are indicated by the horizontal bars. The difference between patients with myeloma and patient controls was highly significant (P = .004). The difference between patients with myeloma and healthy controls was also significant (P = .01).

Elevated concentrations of syndecan-1 and HGF in the bone marrow of patients with myeloma.

Serum or plasma from bone marrow aspirates of 35 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM), 21 controls with other diseases, and 14 healthy controls were analyzed by ELISA for syndecan-1 (A). Median levels are indicated by the horizontal bars. The difference between patients with myeloma and patient controls was highly significant (P = .002). The difference between patients with myeloma and healthy controls was highly significant (P = .001). (B) HGF. Median levels are indicated by the horizontal bars. The difference between patients with myeloma and patient controls was highly significant (P = .004). The difference between patients with myeloma and healthy controls was also significant (P = .01).

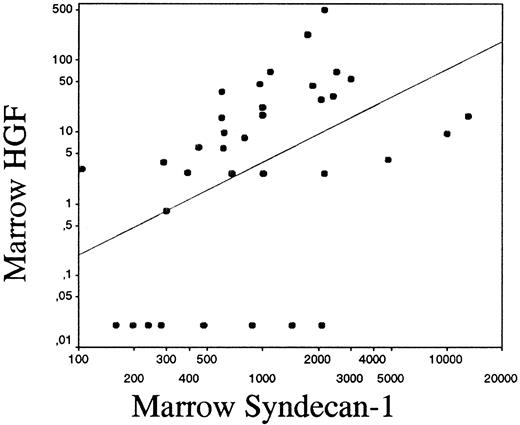

As shown in Figure 1B, 50% of patients with myeloma had elevated HGF levels in the marrow (ie, above mean + 2 SD of healthy controls = 11 ng/mL). The median level of HGF in the marrow was elevated (6 ng/mL, range 0.15-500 ng/mL), compared with the patient controls (1.4 ng/mL, range 0.15-14 ng/mL), P = .004 and healthy controls (1.1 ng/mL, range 0.15-17 ng/mL),P = .01. The difference between the groups was also significant regarding mean values (mean HGF 34 ng/mL, 3.45 ng/mL, and 2.4 ng/mL in the myeloma, patient control, and healthy control groups, respectively, P = .03 for both comparisons). Levels of HGF and syndecan-1 did not differ between plasma and serum. Furthermore, there was a significant correlation between HGF and syndecan-1 levels in the bone marrow of pateints with myeloma (r = 0.53,P < .001), even when the 8 samples that did not contain HGF were included in the statistical analysis, as shown in Figure2.

Correlation between syndecan-1 and HGF in the bone marrow.

Correlation between syndecan-1 and HGF in the bone marrow of patients with myeloma on a logarithmic scale (r = 0.53,P < .001). The drawn line indicates the best fit for linear regression.

Correlation between syndecan-1 and HGF in the bone marrow.

Correlation between syndecan-1 and HGF in the bone marrow of patients with myeloma on a logarithmic scale (r = 0.53,P < .001). The drawn line indicates the best fit for linear regression.

Syndecan-1 is present in supernatants and on the cell surface of myeloma cell lines

Five of 6 myeloma cell lines tested shed syndecan-1. The secretion varied from 10 ng/106 cells after 72 hours in the case of JJN-3 cells to 247 ng/106 cells after 72 hours in the case of U-266 cells. All 5 cell lines also expressed syndecan-1 on the cell surface, as depicted in Table 1.

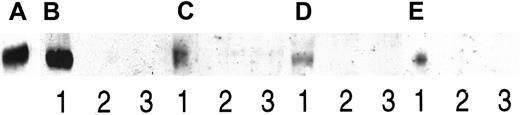

Coprecipitation of syndecan-1 and hepatocyte growth factor

For these experiments, 2 cell lines known to secrete both syndecan-1 and HGF were chosen. Also, pleural effusions from 2 patients with myeloma, known to contain both syndecan-1 and HGF, were included. In all 4 cases, HGF was precipitated by an antibody directed against syndecan-1, as demonstrated in Figure 3. No HGF could be detected when heparin was added in excess amounts to the samples, thus competitively displacing syndecan-1 from HGF, or when an irrelevant antibody was used for the precipitation. In conclusion, these results indicate that when both HGF and syndecan-1 are produced in soluble forms, a portion of the HGF exists in a noncovalent complex with syndecan-1.

Coprecipitation of syndecan-1 and HGF.

Two myeloma cell lines and pleural fluid from 2 patients with myeloma were examined for complexes of syndecan-1 and HGF by coprecipitation. Proteins on the blot were, in all cases, stained with anti-HGF antibodies. Protein was immunoprecipitated with the anti–syndecan-1 antibody BB-4 (lane 1), BB-4 in the presence of heparin (lane 2), and an irrelevant antibody (lane 3). Panels A-E consist of (A) 3 ng of purified HGF as a control, (B) immunoprecipitates from the ANBL-6 cell line, and (C) immunoprecipitates from the JJN-3 cell line. (D) and (E) are immunoprecipitates from patients with myeloma 1 and 2, respectively.

Coprecipitation of syndecan-1 and HGF.

Two myeloma cell lines and pleural fluid from 2 patients with myeloma were examined for complexes of syndecan-1 and HGF by coprecipitation. Proteins on the blot were, in all cases, stained with anti-HGF antibodies. Protein was immunoprecipitated with the anti–syndecan-1 antibody BB-4 (lane 1), BB-4 in the presence of heparin (lane 2), and an irrelevant antibody (lane 3). Panels A-E consist of (A) 3 ng of purified HGF as a control, (B) immunoprecipitates from the ANBL-6 cell line, and (C) immunoprecipitates from the JJN-3 cell line. (D) and (E) are immunoprecipitates from patients with myeloma 1 and 2, respectively.

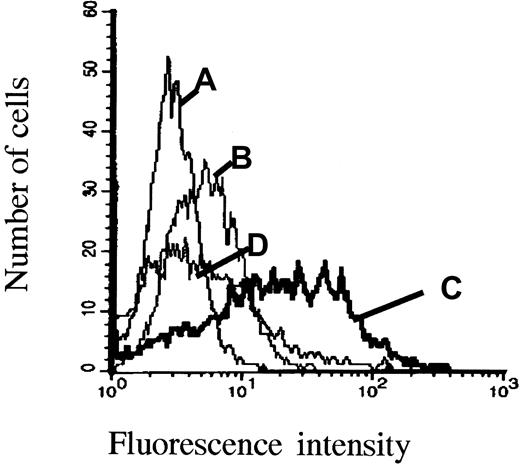

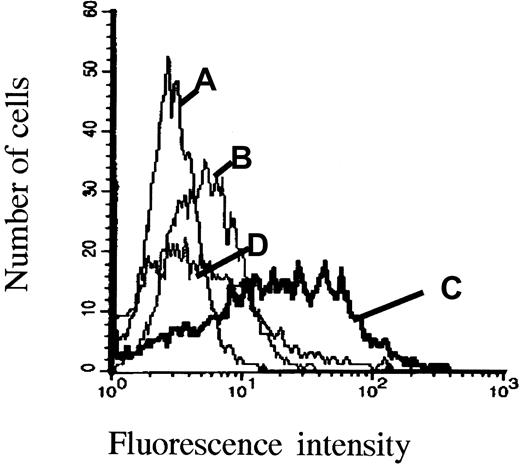

Cell surface syndecan-1 binds hepatocyte growth factor

ARH-77neo and ARH-77syn-1 cells were incubated with HGF. As shown in Figure 4, ARH-77neo cells, which do not express syndecan-1, bound little HGF on their surface as determined by flow cytometry (Figure4B). In contrast, the syndecan-1–transfected cells clearly bound HGF after HGF incubation (Figure 4C). Furthermore, removal of heparan sulfate chains from the surface of ARH-77syn-1 cells with heparitinase abolished HGF binding (Figure 4D).

Expresssion of cell surface syndecan-1 increases HGF binding by ARH-77 cells.

ARH-77neo and ARH-77syn-1 cells were incubated with HGF, washed, and labeled with the HGF antibody 3F4 and FITC-conjugated goat antimouse antibody. (A), ARH-77syn-1cells labeled with an irrelevant antibody and (B) ARH-77neocells, which do not express syndecan-1, were faintly stained with the anti-HGF antibody, in contrast to (C) ARH-77syn-1 cells, which express large amounts of syndecan-1 on the surface and were stained with the anti-HGF antibody. (D) ARH-77syn-1 cells do not bind HGF when they are treated with heparitinase (0.01 U/106 cells, 30 minutes) before HGF incubation.

Expresssion of cell surface syndecan-1 increases HGF binding by ARH-77 cells.

ARH-77neo and ARH-77syn-1 cells were incubated with HGF, washed, and labeled with the HGF antibody 3F4 and FITC-conjugated goat antimouse antibody. (A), ARH-77syn-1cells labeled with an irrelevant antibody and (B) ARH-77neocells, which do not express syndecan-1, were faintly stained with the anti-HGF antibody, in contrast to (C) ARH-77syn-1 cells, which express large amounts of syndecan-1 on the surface and were stained with the anti-HGF antibody. (D) ARH-77syn-1 cells do not bind HGF when they are treated with heparitinase (0.01 U/106 cells, 30 minutes) before HGF incubation.

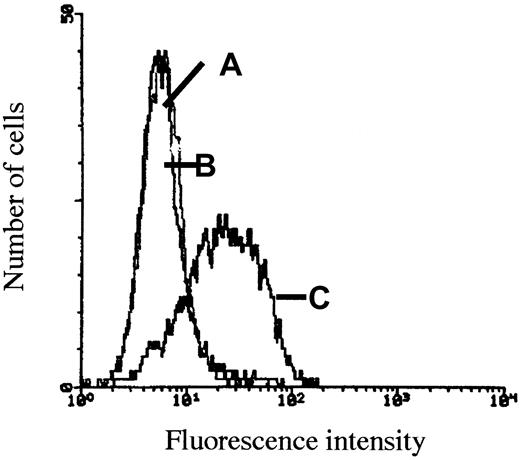

Mobilization of hepatocyte growth factor by soluble syndecan-1

The myeloma cell line JJN-3 produces large amounts of HGF, and HGF can readily be detected on the cell surface by flow cytometry. Washing the cells with soluble heparin releases the HGF from the cell surface.21 As shown in Figure5, washing the cells with purified syndecan-1 releases HGF from the cell surface in an identical manner, indicating that excess soluble syndecan-1 may displace cell-bound HGF.

Mobilization of cell-bound HGF by soluble syndecan-1.

The myeloma cell line JJN-3 produces large amounts of HGF that can be detected on the cell surface by flow cytometry. Before incubation with anti-HGF antibody 3F4 and labeling with FITC-conjugated antimouse antibody, cells were washed with (A) 10 μg/mL soluble heparin, which releases the HGF from the cell surface, (B) 10 μg/mL purified syndecan-1, which releases HGF from the cell surface in an identical manner, and (C) PBS, leaving HGF on the cell surface.

Mobilization of cell-bound HGF by soluble syndecan-1.

The myeloma cell line JJN-3 produces large amounts of HGF that can be detected on the cell surface by flow cytometry. Before incubation with anti-HGF antibody 3F4 and labeling with FITC-conjugated antimouse antibody, cells were washed with (A) 10 μg/mL soluble heparin, which releases the HGF from the cell surface, (B) 10 μg/mL purified syndecan-1, which releases HGF from the cell surface in an identical manner, and (C) PBS, leaving HGF on the cell surface.

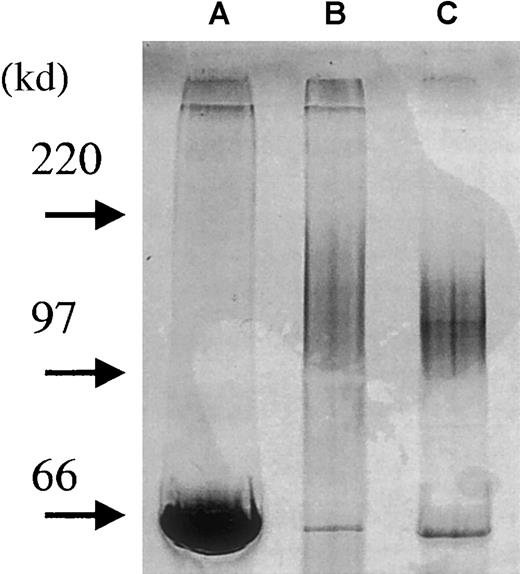

Isolation and purity of syndecan-1 ectodomain

To study the effects of soluble syndecan-1 ectodomain in a biologic system, we purified the proteoglycan from the supernatant of the U-266 myeloma cell line. Medium from U-266 cell cultures was subjected to Q-sepharose chromatography to remove serum proteins and reduce the volume of the sample. At 0.5 to 0.7 mol/L NaCl, a single peak was eluted containing syndecan-1 as assayed by ELISA. The positive fractions were pooled and further separated on a B-B4 immunoaffinity column. Figure 6 illustrates the purity of the samples at each level of this process, showing a broad but single smear on GAG staining of the final syndecan-1 product. There was no visible staining of other bands by a highly sensitive silver staining method (data not shown), suggesting a high degree of purity in the final product.

Purification of syndecan-1 from U-266 cell line.

Soluble syndecan-1 was purified from conditioned medium of U-266 myeloma cells. Four microliters of sample from each purification step was loaded onto a precasted gel (4% to15%). Proteoglycans were detected by combined alcian blue/silver staining.27 By this procedure, GAG chains stain before proteins. The development step was stopped after approximately 2 minutes in this experiment, therefore mainly GAG chains and albumin appear. Lane A: conditioned medium from U-266 cells. Lane B: after Q-sepharose column to remove serum proteins and reduce the volume of the sample. Lane C: after purification of the sample on a B-B4 immunoaffinity column (albumin added to sample after purification).

Purification of syndecan-1 from U-266 cell line.

Soluble syndecan-1 was purified from conditioned medium of U-266 myeloma cells. Four microliters of sample from each purification step was loaded onto a precasted gel (4% to15%). Proteoglycans were detected by combined alcian blue/silver staining.27 By this procedure, GAG chains stain before proteins. The development step was stopped after approximately 2 minutes in this experiment, therefore mainly GAG chains and albumin appear. Lane A: conditioned medium from U-266 cells. Lane B: after Q-sepharose column to remove serum proteins and reduce the volume of the sample. Lane C: after purification of the sample on a B-B4 immunoaffinity column (albumin added to sample after purification).

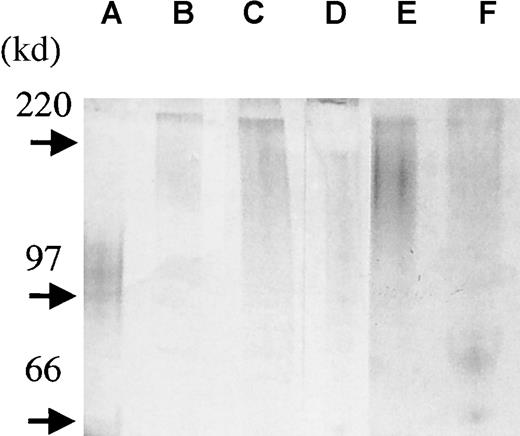

In addition, we isolated syndecan-1 from the bone marrow plasma of 3 patients with myeloma and the pleural fluid of 2 patients with myeloma to assess the size and to establish the intactness of the molecule. In this protocol, we acidified our samples before adding DEAE beads (pH 4.5). At this pH, only highly negatively charged molecules such as GAG chains remain negative and thereby bind the beads. We analyzed the presence of syndecan-1 by ELISA in the samples before DEAE bead purification, and levels varied between 700 ng/mL and 5 μg/mL. After the addition of DEAE beads, no syndecan-1 could be detected in these samples by ELISA, indicating that syndecan-1 had bound the beads and thus existed as an intact, GAG-carrying molecule. When samples were further purified with the anti–syndecan-1 antibody B-B4, syndecan-1 was visualized by GAG-chain staining and appeared as a broad smear between 250 to 150 kd (Figure 7). Thus, syndecan-1 in the marrow and pleural fluid at least in part exists in an intact form, somewhat larger than syndecan-1 purified from the U-266 myeloma cell line. Also, there seems to be a variation in syndecan-1 size among patients.

Syndecan-1 isolated from patient samples exists in an intact form.

To assess the size and to establish the intactness of the syndecan-1 in vivo, syndecan-1 was isolated from bone marrow plasma of 3 patients with myeloma (lanes b-d) and pleural fluid from 2 patients with myeloma (lanes e-f). Purified syndecan-1 from the U-266 cell line is shown in lane a. Four microliters of each sample was loaded onto a precasted gel (4% to 15%). Proteoglycans were detected by combined alcian blue/silver staining.27

Syndecan-1 isolated from patient samples exists in an intact form.

To assess the size and to establish the intactness of the syndecan-1 in vivo, syndecan-1 was isolated from bone marrow plasma of 3 patients with myeloma (lanes b-d) and pleural fluid from 2 patients with myeloma (lanes e-f). Purified syndecan-1 from the U-266 cell line is shown in lane a. Four microliters of each sample was loaded onto a precasted gel (4% to 15%). Proteoglycans were detected by combined alcian blue/silver staining.27

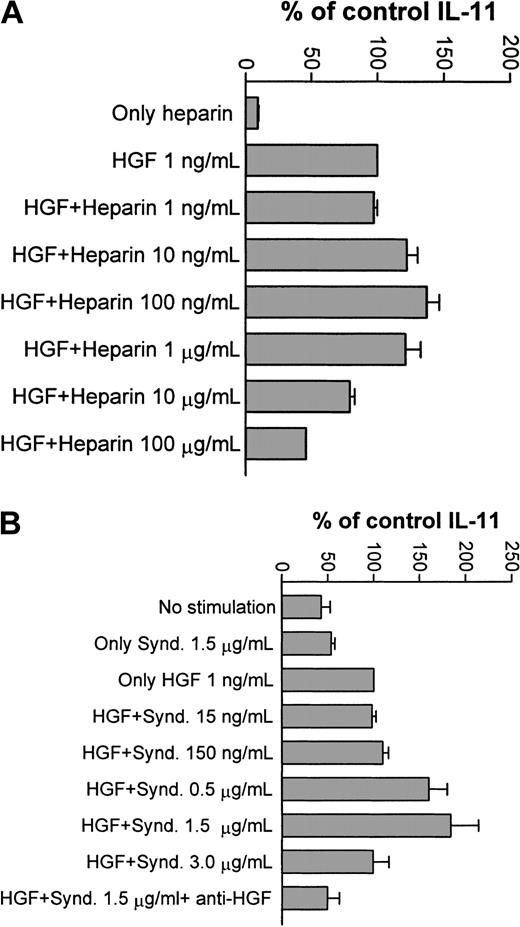

Syndecan-1 modulates hepatocyte growth factor bioactivity in vitro

As recently reported, HGF is a potent stimulator of IL-11 secretion by the osteoblastic cell line Saos-2.21 Effects of HGF can be discerned at concentrations as low as 0.3 to 1 ng/mL, with optimal effects in the 1 to 10 ng/mL range. To study whether the binding of HGF to heparin and syndecan-1 influences this biologic activity of HGF, 2 types of experiments were performed.

First, heparin at varying concentrations was added to the culture medium. As demonstrated in Figure 8A, the effect of 1 ng/mL HGF was potentiated at 10 to 1000 ng/mL of heparin. In contrast, higher concentrations of heparin (10 and 100 μg/mL) inhibited the HGF effect. Heparin alone, at any of the studied concentrations, had no influence on IL-11 production (not shown). Thus, low concentrations of heparin potentiated the biologic activity of HGF, whereas higher concentrations had an inhibitory effect on HGF activity.

Effects of heparin and syndecan-1 on HGF-induced IL-11 production by Saos-2 cells.

(A) Saos-2 cells were stimulated with HGF 1 ng/mL and varying concentrations of heparin, and IL-11 concentration in the supernatants were determined by ELISA. Bars represent percentage of control IL-11 production in cells receiving only HGF (1 ng/mL). Results are graphed as mean + SD of 3 experiments. A potentiation of the HGF effect was seen at 10 to 1000 ng/mL of heparin. Higher concentrations of heparin inhibited the HGF effect. Heparin alone had no effect on IL-11 production. (B) Saos-2 cells were stimulated with HGF 1 ng/mL and varying concentrations of purified syndecan-1 (Synd.). IL-11 concentrations in the supernatants were determined by ELISA. Bars represent percentage of control IL-11 production measured in cells receiving only HGF (1 ng/mL). Results are graphed as mean + SD of 4 experiments. A potentiation of the HGF effect was seen at 150 to 1500 ng/mL of syndecan.

Effects of heparin and syndecan-1 on HGF-induced IL-11 production by Saos-2 cells.

(A) Saos-2 cells were stimulated with HGF 1 ng/mL and varying concentrations of heparin, and IL-11 concentration in the supernatants were determined by ELISA. Bars represent percentage of control IL-11 production in cells receiving only HGF (1 ng/mL). Results are graphed as mean + SD of 3 experiments. A potentiation of the HGF effect was seen at 10 to 1000 ng/mL of heparin. Higher concentrations of heparin inhibited the HGF effect. Heparin alone had no effect on IL-11 production. (B) Saos-2 cells were stimulated with HGF 1 ng/mL and varying concentrations of purified syndecan-1 (Synd.). IL-11 concentrations in the supernatants were determined by ELISA. Bars represent percentage of control IL-11 production measured in cells receiving only HGF (1 ng/mL). Results are graphed as mean + SD of 4 experiments. A potentiation of the HGF effect was seen at 150 to 1500 ng/mL of syndecan.

Next, similar experiments were performed with purified syndecan-1. As shown in Figure 8B, the same bell-shaped stimulation and inhibition of IL-11 secretion was seen, with a clear potentiation of the effect at 1.5 μg/mL syndecan-1. This effect was readily inhibited by the addition of anti- HGF polyclonal antibody. Syndecan-1 alone did not influence the IL-11 production. Taken together, these results indicate that the observed effect required a complex of both syndecan-1 and HGF.

Discussion

A number of cytokines with proven or possible effects on the biology of multiple myeloma bind to heparin and heparan sulfate (review in Taipale and Keski-Oja1). They include cytokines with effects on myeloma cell proliferation (b-FGF28), on angiogenesis (vascular endothelial growth factor,29 b-FGF, HGF), and on bone metabolism, (HGF,21 transforming growth factor-β30 bone morphogenetic protein-2,31osteoprotegerin32). Thus, soluble syndecan-1 may participate in the pathology of the disease by modulating cytokine activity within the bone marrow, as shown here for HGF.

This study shows that soluble syndecan-1 is present at high concentrations in the bone marrow of patients with myeloma. We also show that this syndecan-1 appears in the marrow as an intact form with GAG chains. Osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and myeloma cells are thus constantly exposed to syndecan-1. In addition, we show that the multipotent cytokine HGF, produced by the myeloma cells, is present in this environment. There was a steep gradient from bone marrow to peripheral blood of both syndecan-1 and HGF (data not shown) in all but 2 patients, suggesting that the marrow was a major source of production of the syndecan-1 and HGF found in the sera of patients with myeloma.18

HGF produced by myeloma cells was shown to form a complex with syndecan-1 shed by the same cells. This phenomenon was present in cell lines as well as in pleural fluid derived from patients with myeloma, and is thus not only an in vitro phenomenon but actually seems to occur in vivo. Furthermore, the interaction was inhibited by excess amounts of heparin, confirming that it was noncovalent and presumably mediated by GAGs. We also found that in ARH-77 cells, the expression of syndecan-1 on the cell surface markedly increased their ability to bind HGF. Previous studies have shown that HGF purified from normal serum exhibits a large molecular form,33,34 suggesting that it is bound to heparin-like molecules found in human blood and on the cell surface.33 However, to our knowledge this is the first study to establish that one such naturally occurring molecule is soluble syndecan-1.

We also demonstrated that HGF bound to the myeloma cell surface is displaced by soluble syndecan-1, as shown by the disappearance of HGF after washing cells with the purified syndecan-1 ectodomain. The displacement of bound HGF from cell surfaces by exogenous heparin,15,21,35 with a resulting rise of HGF in serum of heparin-treated individuals has been extensively studied.9-12 Here we show that in multiple myeloma, soluble syndecan-1 is present in the marrow in up to microgram concentrations. Presumably it can act in a manner analogous to soluble heparin, carrying HGF to locations distant from the myeloma cell. In addition, HGF in an unbound form is rapidly cleared from the circulation,36 but bound to heparin, its half-life is considerably increased,36 37 Thus, the soluble syndecan-1 probably keeps the myeloma-derived HGF in solution both within the bone marrow compartment and in the circulation.

It is known that the binding of HGF to its signaling receptor, c-Met, is modulated by cell surface heparin-like molecules.35,38Cells lacking heparan sulfate respond to HGF with reduced efficiency, and exogenous GAG has been shown to enhance HGF activity.39,40 It has recently been reported that HGF signaling may not only be modulated by HSPGs but in some systems actually requires an intact proteoglycan structure located in close apposition to cell surface c-Met for signaling.41 However, the effect of soluble heparin is dependent on the stochiometric relationship between HGF and GAG. The HGF effect may be potentiated at low GAG concentrations that favor receptor dimerization42,43 but be inhibited at high GAG concentrations, where receptor dimerization is prevented.35 44-46

We found that the stochiometric relationship between syndecan-1 and HGF was important for the biologic activity of HGF. We have previously reported that HGF alone induces IL-11 secretion from osteoblasts in a dose-dependent fashion.21 Interestingly, at syndecan-1 concentrations similar to those present in the bone marrow microenvironment (in the order of 1 μg/mL), the HGF effect on IL-11 production was potentiated, whereas it was inhibited by higher concentrations of syndecan-1. This was in agreement with our findings that used heparin in the same system. IL-11 has been shown to stimulate the formation of osteoclast-like cells,47 and thus the interaction between syndecan-1 and HGF could play a role in the regulation of osteoclast formation in myeloma. However, the fact that syndecan-1 modulates HGF activity as shown here may also be important for the angiogenic48-50 and “scattering”46,51 52 effects of this cytokine.

Importantly, a recent publication28 shows that physiologic degradation of syndecan-1 can alter its functional interactions with cytokines. We have shown here that syndecan-1 isolated from patients at least in part appears as an intact form with GAG chains and thus the biologic effects of marrow syndecan-1 can be expected to resemble that of intact syndecan-1 isolated from the myeloma cell line. However, our model system with the Saos-2 cell line can only draw conclusions about the effects of this intact cell-line– derived syndecan-1. So, although we have now also shown that the syndecan-1 shed in the marrow is present in an intact form, we cannot exclude the possibility that this syndecan-1 is also partly cleaved in the marrow. We have not studied the effects of such possible cleavage products. These important, but complex, issues are subject to further study.

In conclusion, the high levels of soluble syndecan-1 found in the bone marrow in multiple myeloma may have at least 2 consequences; one is the mobilization of growth factors from cell surfaces and extracellular matrix as shown here for HGF. In addition, it may modulate the biologic activity of growth factors either in a positive or negative manner, depending on the stochiometric relationship between syndecan-1 and growth factor.

Acknowledgments

We thank Berit Flatvad-Størdal and Hanne Hella for excellent technical assistance. We also thank Dr Tore Amundsen for his enthusiastic participation in the bone marrow sampling.

Supported by grants from the Norwegian Cancer Society (C.S., M.B., Ø.H., H.H.-H.), Rakel and Otto Kr. Bruuns legat, Blix legat and The Cancer Fund, University Hospital of Trondheim.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Carina Seidel, Institute of Cancer Research and Molecular Biology, Medisinsk-Teknisk Senter, 7489 Trondheim, Norway; email: carinas@medisin.ntnu.no.