Abstract

Platelet GP Ibα and leukocyte P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 (PSGL-1) are membrane mucins with a number of structural and functional similarities. It was investigated whether, like GP Ibα, PSGL-1 is affected by a variable number of tandem repeat polymorphism in its mucin-like region. By polymerase chain reaction amplification of the genomic region encoding the PSGL-1 repeats, 3 allelic variants were identified in the human population. The 3 alleles—A, B, and C—from largest to smallest, contained 16, 15, and 14 decameric repeats, respectively, with the B variant lacking repeat 2 and the C variant retaining repeat 2 but lacking repeats 9 and 10. Allele frequencies were highest for the A variant and lowest for the C variant in the 2 populations studied (frequencies of 0.81, 0.17, and 0.02 in white persons and 0.65, 0.35, and 0.00 in Japanese). Thus, PSGL-1 is highly polymorphic and contains a structural polymorphism that potentially indicates functional variation in the human population.

Introduction

Platelet glycoprotein (GP) Ibα and leukocyte P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 (PSGL-1) have a number of interesting similarities. Both mediate the attachment of blood cells from the bulk flow onto the blood vessel wall—GP Ibα attaching platelets to the subendothelium through binding von Willebrand factor (vWF)1 and PSGL-1 tethering leukocytes to P-selectin on the surface of activated endothelium.2 Both also mediate rolling interactions over surfaces coated with their respective ligands.3,4 To tether cells to these surfaces, each receptor has independently evolved a mucin-like stalk that allows the ligand-binding region to be extended above the forest of other proteins on the plasma membrane. Both stalks have arisen by similar mechanisms: tandem repetition of short amino acid stretches containing threonine, serine, and proline within heavily glycosylated, mucin-like sequences. The basic repeated unit in GP Ibα comprises 13 amino acids, and in PSGL-1 it contains 10 amino acids. In human populations, GP Ibα is polymorphic based on variable numbers of these tandem repeats (VNTRs),5 a polymorphism that has been shown to be a marker for increased susceptibility to cardiovascular disease.6 We hypothesized that PSGL-1 could similarly be affected by a VNTR polymorphism.

Study design

Study population

All subjects signed informed consent documents, and the institutional review board of the Baylor College of Medicine approved the protocols. Two independent populations were studied, the first comprising 141 unrelated persons in the CEPH (Centre d'Etude du Polymorphisme Humain) population and the second comprising 68 apparently healthy Japanese blood donors.

Genotyping

A set of oligonucleotide primers was designed to encompass the decameric consensus repeat sequences in exon 2 of the PSGL-1gene. The sequences of the forward and reverse primers were 5′-CCTGTCCACGGATTCAGC-3′ and 5′-GGGAATGCCCTTGTGAGTAA-3′ (corresponding to nucleotide sequences 576-593 and 1134-1115, respectively).7 DNA was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using 100 ng DNA, 200 nM each primer, 200 μM each dNTP, 1.0 μM MgCl2, and 1.5 U Taq DNA polymerase for 35 cycles. The melting temperature was 94° C for 30 seconds, annealing temperature was 62°C for 45 seconds, and the extension temperature was 72°C for 90 seconds. PCR products were separated on 2% agarose gels and were visualized by ethidium bromide staining. PCR products from homozygous persons were sequenced.

Results and discussion

Identification, frequency, and molecular basis of a PSGL-1 VNTR polymorphism

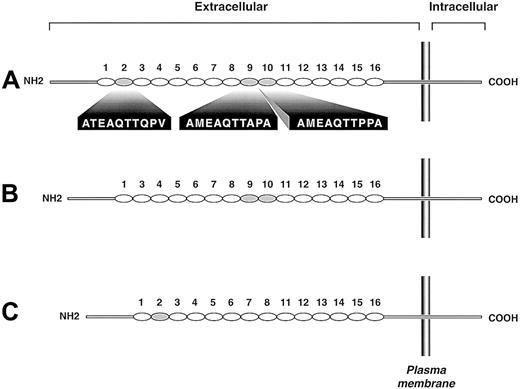

Genotyping was successfully completed in all 141 subjects in the CEPH population and 68 Japanese blood donors. Gel electrophoresis of the PCR products identified 3 bands—558 bp, 528 bp, and 498 bp (not shown)—which were labeled as alleles A, B, and C, respectively. Sequence analysis showed that the A allele was identical to the form stored in the GenBank database (accession number U25956), the B allele lacked the second tandem repeat (ATEAQTTQPV), and allele C retained the second tandem repeat but lacked repeats 9 and 10 (AMEAQTTAPA and AMEAQTTPPA, respectively) (Figure 1). Allele and genotype frequencies are shown in Table1. For these studies, thePSGL-1 genes were sequenced from 2 AA homozygotes, 1 BB homozygote, 1 CC homozygote, and 1 BC heterozygote. Thus, 4 A alleles and 3 each of the B and C alleles were sequenced. Although only 3 PCR products were detected in 209 subjects, it remains possible that other alleles exist of the same length but lack other repeats or that the polypeptide is also polymorphic at the level of single amino acid changes.

Schematic depiction of the 3 PSGL-1 polymorphic variants.

Each decameric repeat is depicted as an oval. The largest variant (A) has 16 repeats, the B variant has 15 repeats (repeat 2 of the A form is missing), and the C variant has 14 repeats (repeats 9 and 10 of the A form are missing). Repeats of the A variant missing in the smaller variants are shaded gray; their sequences are given below the A variant.

Schematic depiction of the 3 PSGL-1 polymorphic variants.

Each decameric repeat is depicted as an oval. The largest variant (A) has 16 repeats, the B variant has 15 repeats (repeat 2 of the A form is missing), and the C variant has 14 repeats (repeats 9 and 10 of the A form are missing). Repeats of the A variant missing in the smaller variants are shaded gray; their sequences are given below the A variant.

This polymorphism thus bears a striking analogy to the VNTR polymorphism of the GP Ibα gene.5,8 Based on analogy to mucins for which physicochemical studies have been carried out, it has been predicted that each added amino acid in the mucin-like region of GP Ibα adds 2.5 Å to the length of the macroglycopeptide stalk, with the addition of three 13-amino acid repeats adding approximately 100 Å to the length of the region.5 With PSGL-1, the difference between the shortest and longest form would not be expected to be as great (approximately 50 Å). Nevertheless, this difference may have an even greater effect on the actual receptor because PSGL-1 forms disulfide-linked dimers and heterozygosity could lead to a disparity in the spatial relationship of the ligand-binding sites on the individual polypeptides of the dimer. One study has suggested that PSGL-1 dimerization is required for the interaction of PSGL-1 with P-selectin,9 but this requirement was not supported by another study.4 Thus, either by changing the distance of important ligand-binding regions from the leukocyte plasma membrane or by affecting the relationship between ligand-binding regions on adjacent polypeptide chains (in a heterozygous person), the PSGL-1 polymorphism is likely to subtly affect binding to P-selectin and, therefore, leukocyte function.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL54218, 9-640-133N, and 96-012-670. J.A.L. and A.J.M. are Established Investigators of the American Heart Association.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

José A. López, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, BCM286, N1319, One Baylor Plaza, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: josel@bcm.tmc.edu.