Human dendritic cell (DC) precursors were engrafted and maintained in NOD/SCID- human chimeric mice (NOD/SCID-hu mice) implanted with human cord blood mononuclear cells, although no mature human DCs were detected in lymphoid organs of the mice. Two months after implantation, bone marrow (BM) cells of NOD/SCID-hu mice formed colonies showing DC morphology and expressing CD1a in methylcellulose culture with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α). The CD34−/CD4+/HLA-DR+ cell fraction in NOD/SCID-hu mouse BM generated CD1a+ cells that were highly stimulatory in mixed leukocyte reactions in culture with GM-CSF and TNF-α. These results suggest a strong potential for NOD/SCID-hu BM to generate human DCs, although DC differentiation may be blocked at the CD34−/CD4+/HLA-DR+ stage.

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) are families of antigen-presenting cells comprising at least 3 members—lymphoid DCs, myeloid DCs, and Langerhans cells.1 All are derived from hematopoietic stem cells and far exceed other similarly derived cells, such as B cells or macrophages, in their capacity to initiate a primary major histocompatibility complex–restricted immune response. DCs appear in small numbers in both lymphoid and nonlymphoid tissues, and their differentiation pathway(s) or specific hematopoietic lineage assignment(s) is not well known. Recently, several investigators successfully used cytokines in vitro to generate human DCs from human CD34+ peripheral and cord blood cells1,2 and human peripheral blood monocytes.3 In vivo differentiation of human DCs, however, has not been well studied. In this paper, we provide evidence that the maturation of human DCs proceeds up to the CD34−/CD4+/HLA-DR+ stage in the bone marrow (BM) of NOD/SCID-human chimeric mice (NOD/SCID-hu mice) and that these CD4+/HLA-DR+ cells can differentiate into phenotypically and functionally mature DCs in vitro in the presence of human cytokines.

Study design

Transplantation

Cord blood mononuclear cells (CBMNCs) were intravenously inoculated into 10- to 14-week-old NOD/SCID mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) that had been given whole-body X-irradiation (0.68 Gy/min, 2.5 to 3.5 Gy). The mice were housed under sterile conditions in air-filtering containers and killed 8 to 12 weeks after the inoculation.

Flow cytometry

Cell surface antigen expression of BM cells from NOD/SCID-hu mice were analyzed by 2- or 3-color flow cytometry with a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) after the cells were stained with various combinations of human-specific monoclonal antibodies to CD1a, CD3, CD4, CD11a, CD11c, CD14, CD 34, HLA-DR, HLA-DQ (Becton Dickinson), CD83 (Coulter Immunology, Hialeah, FL), and streptavidin-RED 670 (Gibco BRL, Rockville, MD), as described previously.4 Irrelevant murine immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) monoclonal antibody (Becton Dickinson) was used for control staining.

In vitro differentiation of DC precursors

BM cells from NOD/SCID-hu mice were cultured in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium with 1% methylcellulose and 20% fetal calf serum in the presence of 100 ng/mL granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and 10 ng/mL tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) (R&D Systems) for 14 days without replenishment of cytokines or medium. Cells of CD4+/HLA-DRlo and CD4+/HLA-DRhigh fractions, both of which were obtained from BM by cell sorting with FACStar (Becton Dickinson), were cultured similarly (but without methylcellulose) for 7 days.

Mixed leukocyte reaction

Cells of sorted and cultured CD4+/HLA-DRlo and CD4+/HLA-DRhigh fractions were washed and irradiated with 15 Gy of X-rays and then used as mixed leukocyte reaction (MLR) stimulator cells. Uncultured mononuclear cells obtained from human adult peripheral and cord blood were similarly irradiated and used. Graded numbers of stimulator cells were cultured for 5 days with 1 × 105 nylon-wool nonadherent allogeneic human T cells in 96-well round-bottom plates supplemented with RPMI 1640 containing 10% human serum. MLRs were evaluated by the level of [3H]-thymidine (NEN Life Science Products, Boston, MA) incorporation during the last 18 hours of culture.5

Results and discussion

Although we were unable to detect human CD1a+ DCs in the BM, spleen, peripheral blood, thymus, or lymph nodes of CBMNC-inoculated mice by flow cytometry, we could detect a significant number of cells exhibiting DC morphology when NOD/SCID-hu BM cells were cultured for 14 days in the presence of human GM-CSF and TNF-α. A significant proportion of the colony-forming cells expressed human CD1a and/or CD14 (data not shown), confirming the existence of human DC precursors in the BM of NOD/SCID-hu mice. Surface phenotypes of the colonies suggested 3 types of DCs—CD1a+/CD14−Langerhans cell-like DCs,1CD1a−/CD14+ monocyte/myeloid DC precursors,1 and CD1alo/CD14+cells, which are likely intermediates in the differentiation of CD1a−/CD14+ monocytes to CD1a+/CD14− DCs6-8 or a subpopulation of mature DCs9,10 that have been identified in the lymph of human skin.10

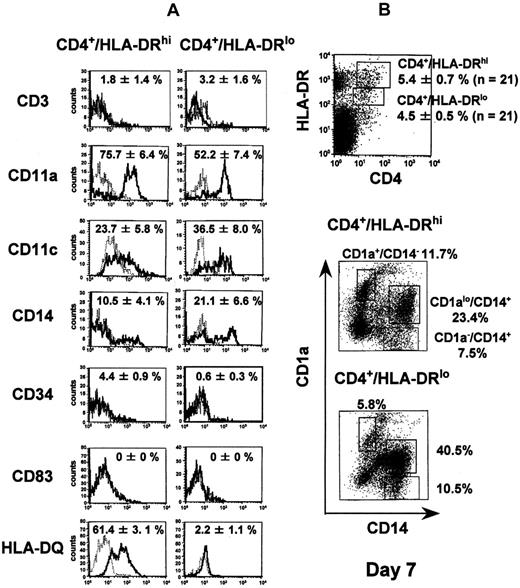

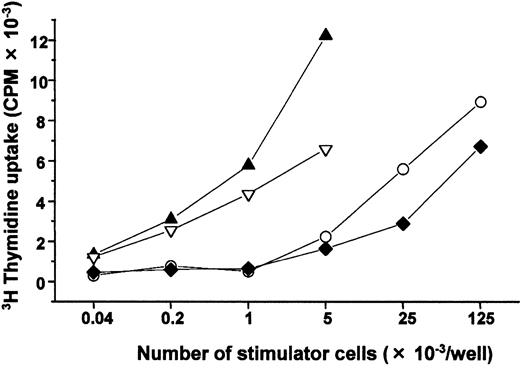

We next examined CD4+/HLA-DR+ cells in the NOD/SCID-hu BM because immature DCs freshly isolated from human peripheral blood are reported to express those antigens.11We subdivided the cells into 2 populations—CD4+/HLA-DRhi and CD4+/HLA-DRlo cells—both of which appeared in about 5% of the nucleated marrow cells. Representative flow cytometry patterns of both populations before and after culture are shown in Figure 1. Both showed significant expression of CD11c but not of CD3, CD34, CD1a, or CD83. Remarkably, only CD4+/HLA-DRhi cells expressed HLA-DQ, and CD14 expression was lower in the CD4+/HLA-DRhifraction than in the CD4+/HLA-DRlo fraction (Figure 1A). Cells cultured from both CD4+/HLA-DRhi and CD4+/HLA-DRlo fractions with GM-CSF and TNF-α contained discrete fractions of CD1a+/CD14−, CD1alo/CD14+, and CD1a−/CD14+ cells on day 7 (Figure 1B) and resembled DCs (showing polarized lamellipodia or homogeneous distribution of dendrites on the cell surface). The preferential expression of HLA-DQ12 and the lower expression of CD14 in CD4+/HLA-DRhi cells, and, following in vitro culture, the higher expression of CD1a+/CD14−in CD4+/HLA-DRhi cells, all suggest that that fraction contained more CD1a+/CD14− DC precursors than did the CD4+/HLA-DRlo fraction. Allogeneic MLRs demonstrated that cultured cells from both fractions were potentially capable of inducing a primary T-cell response (Figure 2). These results suggest that the NOD/SCID-hu BM has a strong potential to generate human DCs, although DC differentiation may be blocked at the CD34−/CD4+/HLA-DR+ stage.

Cell-surface phenotypes of CD4+/HLA-DRhi and CD4+/HLA-DRlo human dendritic cell precursors before and after in vitro culture in the presence of human GM-CSF and TNF-α.

(A) BM cells obtained from NOD/SCID mice that had been inoculated with human CBMNCs were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled irrelevant murine IgG1, anti-CD3, anti-CD11a, anti-CD14, anti-CD34, or anti–HLA-DQ antibody, and phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled anti–HLA-DR antibody and biotinylated anti-CD4 antibody plus streptavidin-RED 670, or, for analysis of CD11c or CD83 expression, with PE-labeled irrelevant murine IgG1, anti-CD11c, or anti-CD83 antibody, and FITC-labeled anti–HLA-DR antibody and biotinylated anti-CD4 antibody plus streptavidin-RED 670. Data acquisition and analysis were performed with Cellquest software (Becton Dickinson). The solid and dotted lines show specific antigen expression and the isotype-matched controls, respectively. The positive rates (mean ± standard error) obtained from 3 independent experiments are represented in the panels. (B) Cells in the CD4+/HLA-DRhi fraction and the CD4+/HLA-DRlo fraction were sorted and cultured for 7 days in the presence of 100 ng/mL GM-CSF and 10 ng/mL TNF-α, and the cultured cells were stained with FITC-labeled CD14 antibody and PE-labeled CD1a antibody. A replicate experiment yielded similar results.

Cell-surface phenotypes of CD4+/HLA-DRhi and CD4+/HLA-DRlo human dendritic cell precursors before and after in vitro culture in the presence of human GM-CSF and TNF-α.

(A) BM cells obtained from NOD/SCID mice that had been inoculated with human CBMNCs were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled irrelevant murine IgG1, anti-CD3, anti-CD11a, anti-CD14, anti-CD34, or anti–HLA-DQ antibody, and phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled anti–HLA-DR antibody and biotinylated anti-CD4 antibody plus streptavidin-RED 670, or, for analysis of CD11c or CD83 expression, with PE-labeled irrelevant murine IgG1, anti-CD11c, or anti-CD83 antibody, and FITC-labeled anti–HLA-DR antibody and biotinylated anti-CD4 antibody plus streptavidin-RED 670. Data acquisition and analysis were performed with Cellquest software (Becton Dickinson). The solid and dotted lines show specific antigen expression and the isotype-matched controls, respectively. The positive rates (mean ± standard error) obtained from 3 independent experiments are represented in the panels. (B) Cells in the CD4+/HLA-DRhi fraction and the CD4+/HLA-DRlo fraction were sorted and cultured for 7 days in the presence of 100 ng/mL GM-CSF and 10 ng/mL TNF-α, and the cultured cells were stained with FITC-labeled CD14 antibody and PE-labeled CD1a antibody. A replicate experiment yielded similar results.

Stimulator activity of cultured CD4+/HLA-DRhi and CD4+/HLA-DRlo human DC precursors in MLR.

Cells in the CD4+/HLA-DRhi fraction (▴) and the CD4+/HLA-DRlo fraction (▿) were cultured under the same conditions described in Figure 1B and analyzed for their stimulatory activity to allogeneic human T cells. Freshly isolated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (○) and allogeneic CBMNC (♦) were also used as MLR stimulator cells. Two replicate experiments yielded similar results. CPM indicates counts per minute.

Stimulator activity of cultured CD4+/HLA-DRhi and CD4+/HLA-DRlo human DC precursors in MLR.

Cells in the CD4+/HLA-DRhi fraction (▴) and the CD4+/HLA-DRlo fraction (▿) were cultured under the same conditions described in Figure 1B and analyzed for their stimulatory activity to allogeneic human T cells. Freshly isolated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (○) and allogeneic CBMNC (♦) were also used as MLR stimulator cells. Two replicate experiments yielded similar results. CPM indicates counts per minute.

In vitro studies suggest that CD34+ CBMNCs differentiate into mature DCs through CD34−/CD1a−/CD14+ or CD34−/CD1a−/CD14− DC precursors and that these precursors require human cytokine stimulation to mature fully.13 Thus, the CD4+/HLA-DRhiand CD4+/HLA-DRlo cells observed in NOD/SCID-hu BM may be arrested at a premature stage of surface phenotype CD34−/CD1a−CD14± since NOD/SCID-hu mice lack the human cytokines. There are other possible explanations for the developmental arrest of DC cells in NOD/SCID-hu mice. The microenvironment may not be suitable for full development of the DC precursors. For example, transendothelial trafficking is essential for DC differentiation,14 but DC precursor migration from BM might be impaired in NOD/SCID-hu mice because of lack of interaction between human adhesion molecules expressed on the DC precursors and mouse endothelial cells. Alternatively, NOD/SCID-hu mice lack human T cells that may be required for the functional maturation of DCs in vivo. It has been reported that the reduced numbers and impaired antigen-presenting ability of DCs in recombination-activating gene-2–deficient mice can be corrected by reinoculating these mice with T cells from normal mice.15 Although further studies are necessary to fully elucidate the DC differentiation process, the NOD/SCID-hu mouse seems to be a suitable model for human DC development in vivo.

We thank Mayumi Maki, Mayumi Mukai, and Makiko Hamamura for their technical assistance, and Drs Gen Suzuki and Donald G. MacPhee for critical advice. This paper is based on research performed at Radiation Effects Research Foundation, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan. Radiation Effects Research Foundation is a private nonprofit foundation funded equally by the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare and the United States Department of Energy through the National Academy of Sciences.

Supported in part by funds for Research Promotion on AIDS Control from the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Masaharu Nobuyoshi, Department of Hematology and Oncology, Division of Clinical Research, Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine, Hiroshima University, 1-2-3 Kasumi, Minami Ward, Hiroshima, 734-8553 Japan; e-mail:nobuyosi@hiroshima-u.ac.jp.