In a variety of cell types, the transcription factor nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) functions as a mediator of stress and immune responses. In endothelial cells (ECs), it controls the expression of genes encoding, eg, cytokines, cell adhesion molecules, and procoagulatory proteins. This study investigates the effect of NF-κB suppression on several pathophysiologic functions of ECs, including inflammation, coagulation, and angiogenesis. A recombinant adenovirus was generated for expression of a dominant negative (dn) mutant of IκB kinase 2 (IKK2), a kinase that acts as an upstream activator of NF-κB. dnIKK2 inhibited NF-κB, resulting in strongly reduced nuclear translocation and DNA binding activity of the transcription factor and lack of expression of several proinflammatory markers, including E-selectin, intercellular adhesion molecule 1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, and interleukin-8. Concomitantly, inhibition of leukocyte binding to dnIKK2-expressing ECs could be demonstrated in a cell adhesion assay. Furthermore, expression of tissue factor as well as the ability to form capillary tubes in a matrigel assay was impaired in dnIKK2-expressing ECs. These data demonstrate that NF-κB is of central importance not only for the inflammatory response but also for a number of other EC functions. Therefore, this transcription factor as well as its upstream regulatory signaling molecules may represent favorable targets for therapeutic interference.

Introduction

Nuclear factor κB (NF-κB)/Rel transcription factors represent an ubiquitously expressed family that modulate the expression of genes involved in diverse cellular functions such as stress response, innate and adaptive immune reactions, and apoptosis. Examples include β-interferon, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, immunoglobulinκ light chain, interleukin-2 (IL-2), major histocompatibility complex I, T-cell receptor, A20, inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP), and acute phase genes (for recent reviews, see Baeuerle,1 de Martin et al,2 and Hatada et al3). Viruses, such as human immunodeficiency virus 1 or human T-cell leukemia virus 1, use NF-κB to control the transcription of their own genes and prevent their host cells from undergoing apoptosis.4 In endothelial cells (ECs), genes dependent on NF-κB include, among others, IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, E-selectin, intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), inducible nitric oxide synthase, cyclooxygenase 2, and tissue factor. In cells of the vasculature, NF-κB can be activated by inflammatory cytokines, bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS), oxidized low-density lipoprotein (LDL), advanced glycation end products, platelet-derived growth factor, and hypoxia/reoxygenation. Several disorders that involve endothelial and smooth muscle cells, such as acute and chronic inflammation and atherogenesis, have been associated with elevated levels of NF-κB.

The NF-κB family includes the mammalian proteins p65 (RelA), RelB, c-Rel, the viral oncogene v-Rel, p50 (NF-κB1), and p52 (NF-κB2), the latter 2 being synthesized as precursors p105 and p100, respectively. They form homodimers or heterodimers that display different affinities for variants of a decameric consensus binding site. In accordance with the importance of its target genes, the activity of NF-κB is tightly controlled. The main mechanism of activation is the regulated translocation of the transcription factor from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Cytoplasmic NF-κB is inactive because of complex formation with proteins of the IκB family (IκBα, IκBβ, and IκBε) that mask the NF-κB nuclear localization signal, thus retaining the NF-κB/IκB complex in the cytoplasm.5 Upon stimulation, IκBα is phosphorylated on 2 serine residues, S32 and S36.6 This activation-induced phosphorylation is accomplished by 2 specific kinases (IKKα/IKK1 and IKKβ/IKK2) and represents a signal for rapid degradation of IκBα through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, thus allowing nuclear translocation of NF-κB.7-11 The IKKs each consist of an amino-terminal kinase domain as well as a central leucine zipper and a carboxy-terminal helix-loop-helix domain. They are, in turn, activated by the upstream mitogen-activated protein 3 (MAP3) kinases NIK (NF-κB inducing kinase) and/or MEKK-1.12,13 However, other kinases have also been reported to be capable of activating the IKKs, including Akt, p90rsk, DNA-PKcs, protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms as well as TAK1 and NF-κB activating kinase (NAK).14-18 Recently, 2 additional IKK-like kinases have been identified, namely TBK1 that binds to TANK (a tumor necrosis factor-α [TNFα] receptor–associated factor) and IKK-i, a LPS-inducible kinase; however, their physiologic function remains to be established.19 20

In transient transfections that use reporter gene assays, mainly IKK2 has been shown to transmit the signal(s) elicited by inflammatory cytokines like TNFα and IL-1 as well as LPS that lead(s) to activation of NF-κB.8 However, biochemical characterization of the consequences of specific IKK2 inhibition in ECs has been difficult to demonstrate. We have used a recombinant adenovirus that allows highly efficient gene transfer into ECs to express a kinase-negative mutant of IKK2 (dnIKK2) that acts as a dominant negative (dn) molecule. ECs expressing dnIKK2 showed strongly impaired responses in different in vitro assays for 3 main properties of ECs, namely inflammation, coagulation, and angiogenesis. This suggests a common key regulatory role for NF-κB in apparently very distinct EC functions.

Materials and methods

EC culture

ECs were isolated from human umbilical veins as described previously21 and grown on gelatin-coated cell culture flasks (Iwaki, Gyondu, Japan) in complete medium 199 supplemented with 20% bovine calf serum, EC growth factor, and heparin. For stimulation, 500 U/mL human recombinant IL-1α, 200 U/mL human recombinant TNFα (both from Genzyme, Cambridge, MA) or 500 ng/mL LPS (Sigma, Vienna, Austria) were used unless indicated otherwise.

Construction of recombinant adenovirus (AdV-dnIKK2)

A human IKK2 complementary DNA (cDNA) was isolated by reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction with a Flag tag added to the 5′ end, using the following primers derived from the published sequence9: Flag-IKK2-1, 5′-aaaagaattcgccaccATGGACTACAAGGACGACGATGACAAGAGCTGGTCACCTTCCCTGA-3′; and Flag-IKK2-2, 5′-aaaatctagaTGAGGCCTGCTCCAGGCAG-3′. To generate dnIKK2, a mutation was introduced in the kinase domain that changed K44 to A, using the primer IKK2mut: 5′-aaaagtcgacgccggcACTGTGCAATTGCAATCTGCTCACCTGT-3′ in polymerase chain reaction and subcloning at the NaeI site. The construct was sequenced, inserted into the adenovirus transfer vector pACCMVpLpASR+, and cotransfected together with pJM17 into 293 cells as described previously.22,23 Resulting adenoviral plaques were tested for IKK2 expression by Western blotting, using an anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma) at a dilution of 1:1000. Purification of a large batch of the recombinant adenovirus was done by 2 consecutive cesium chloride centrifugations as described.24

Transduction of human umbilical vein–derived ECs

Postconfluent human umbilical vein–derived ECs (HUVECs) were washed once with complete phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with AdV-dnIKK2 or control adenovirus (AdV-GFP [green fluorescent protein]25) at a multiplicity of infection of 100 in PBS. After 30 minutes at 37°C, the adenovirus was washed off, and fresh growth medium was added. Cells were further cultivated for 2 to 3 days before stimulation with cytokines and performing the assay.

Immunofluorescence

Adenovirus-transduced or control HUVECs were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100, blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS, and stained with rabbit anti-p65 antibody (sc-109; Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, CA) at a dilution of 1:100 followed by incubation with goat antirabbit Cy3-labeled second antibody (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) at a dilution of 1:5000. Microscopic examination was carried out, using Rhodamine filters that allow discrimination of Cy3 fluorescence from the GFP control adenovirus.

RNA isolation and Northern blotting

Total RNA was extracted from HUVECs, fractionated on formaldehyde/agarose gels, transferred to Hybond N membranes (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), and hybridized to random-primed cDNA probes for IL-8, VCAM-1, E-selectin, and glyceraldehyde phophate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as described.26 Equivalent loading and transfer of RNA was confirmed by hybridization with a GAPDH probe.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in Laemmli buffer, separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on 12.5% Minigels (Mini-Protean II; Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The following antibodies were used in the respective dilutions: anti–ICAM-2 (Santa Cruz Biotech; 1:1500); anti-IκBα (Santa Cruz Biotech; 1:500); anti-Flag (Sigma; 1:1000); anti-IKK2 (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotech), and peroxidase-conjugated donkey antirabbit or donkey antimouse second antibodies (1:5000; Amersham) followed by enhanced chemiluminescence detection (ECL-Plus; Amersham).

Nuclear extracts and electrophoretic mobility shift assay

HUVECs were transduced either with control virus or with AdV-dnIKK2, stimulated 2 days later with 500 ng/mL TNFα for 1 hour, or left unstimulated, and nuclear proteins were extracted as described.27 A double-stranded oligonucleotide that represented the BS-2 NF-κB binding site (underlined) from the porcine IκBα promoter8 (5′-aattcGGCTTGGAAATTCCCCGAGCg-3′) was labeled by filling in the EcoRI overhangs with Klenow enzyme in the presence of radioactive nucleoside triphosphates, and 0.2 ng (100.000 cpm) was used per binding reaction. The resulting complexes were separated on 5% native polyacrylamide gels.

Cell enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

HUVECs were grown in 6-well plates and transduced with AdV-dnIKK2 or AdV-GFP, passaged the next day into 96-well microtiter plates, and 2 days later cell enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed after stimulation with LPS essentially as described.24 Briefly, cells were fixed with glutaraldehyde and blocked overnight in PBS/5% BSA. Expression of cell adhesion molecules was determined by using the respective antibodies (anti–VCAM-1, anti–E-selectin, anti–ICAM-1) at 1:500 dilution (R&D Systems, Abingdon, United Kingdom), anti–ICAM-2 (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotech), and peroxidase-coupled second antibodies (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), followed by o-nitrophenylene-diamine detection. Equal numbers of cells in the assay were determined by staining with sulforhodamine B (Sigma).

Cell adhesion assay

HUVECs grown in 24-well microtiter plates were infected with AdV-dnIΚΚ2 or with control virus. Three days later, cells were stimulated with 500 U/mL IL-1α (Genzyme) for 4 hours or left unstimulated. HL-60 cells were labeled with 5-chloromethylfluorescein diacetate (CMFDA; Molecular Probes Inc, Eugene, OR) at a final concentration of 5 μM for 20 minutes at 37°C as recommended by the manufacturer. Labeled HL-60 cells (1 × 106) were added to the HUVEC cultures in a total volume of 0.4 mL and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. After 2 washes with PBS, pictures from the adhered HL-60 cells were taken under the fluorescence microscope, using fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) filters.

Determination of procoagulant activity

AdV-GFP– and AdV-dnIKK2–transduced HUVECs were stimulated for 6 hours with 500 ng/mL LPS, harvested, collected by centrifugation, and resuspended in clotting buffer (12 mM Na-acetate/7 mM Na-barbital/130 mM NaCl, pH = 7.4). Cell suspension (100 μL) was combined with 100 μL plasma (Sigma) and 100 μL of 20 mM CaCl2 and incubated at 37°C. Time until clot formation was recorded and transformed into thromboplastin units, using a standard curve. Mean values and standard deviations were calculated from triplicate experiments.

Tube formation assay

Formation of endothelial capillary tubelike structures was analyzed, using basement membrane matrix (Matrigel; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Wells of 48-well culture cluster dishes (Costar, Cambridge, MA) were coated with 100 μL/well and allowed to solidify for 30 minutes at 37°C. HUVECs, after being starved for 24 hours in 5% SCS M199, were seeded on polymerized Matrigel (2 × 104 cells/well) and further propagated for 16 hours, then fixed in PBS containing 3% formaldehyde and 2% sucrose.28 As a control for viability after adenovirus treatment, aliquots of transduced cells were plated on gelatin-coated plates.

Results

Construction and characterization of a recombinant dnIKK2-expressing adenovirus

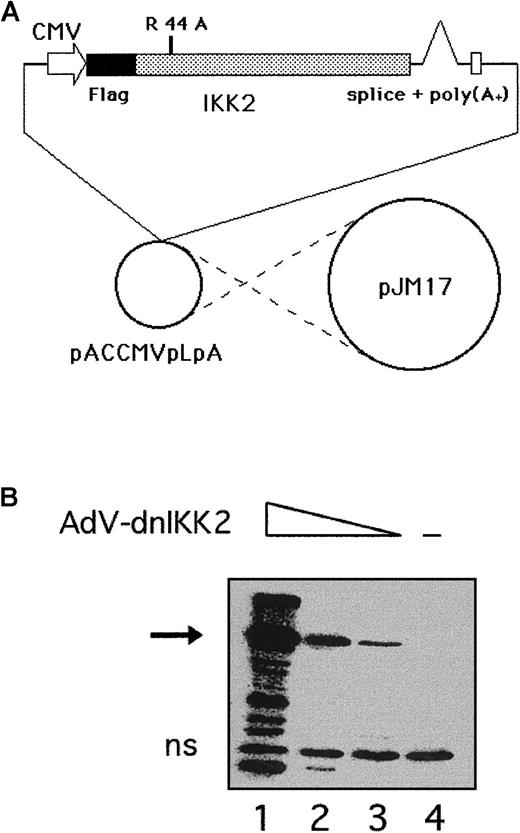

Cotransfection of Flag-tagged dnIKK2, cloned into the adenovirus transfer vector pACCMVpLpASR+, together with the plasmid pJM17 into 293 cells resulted in the generation of recombinant adenovirus (Figure 1A). After subcloning of the virus pool, individual clones were obtained, 293 cells were infected with different amounts of virus and analyzed by Western blotting for dnIKK2 expression (Figure 1B). A large batch of virus was prepared from one positive clone and used in the subsequent experiments. To achieve expression of dnIKK2 in ECs, a multiplicity of infection of 100 with AdV-dnIKK2 was used for HUVECs to obtain 90% to 100% positive cells as determined by immunoperoxidase staining of Flag-dnIKK2, using an anti-Flag antibody (not shown).

Construction of a recombinant adenovirus for expression of dnIKK2 (AdV-dnIKK2).

(A) A dominant-negative form of IKK2 was generated by mutating K44 to A, and a Flag tag engineered to its 5′ end. The construct was cloned into the adenovirus transfer vector pACCMVpLpASR and cotransfected together with pJM17 into 293 cells.22 (B) Western blot analysis of Flag-dnIKK2 expression in 293 cells. Cells were incubated with deceasing amounts of plaque-purified AdV-dnIKK2 (lanes 1-3; lane 4: no virus). The Flag-dnIKK2–specific band is indicated by an arrow. ns indicates nonspecific.

Construction of a recombinant adenovirus for expression of dnIKK2 (AdV-dnIKK2).

(A) A dominant-negative form of IKK2 was generated by mutating K44 to A, and a Flag tag engineered to its 5′ end. The construct was cloned into the adenovirus transfer vector pACCMVpLpASR and cotransfected together with pJM17 into 293 cells.22 (B) Western blot analysis of Flag-dnIKK2 expression in 293 cells. Cells were incubated with deceasing amounts of plaque-purified AdV-dnIKK2 (lanes 1-3; lane 4: no virus). The Flag-dnIKK2–specific band is indicated by an arrow. ns indicates nonspecific.

Expression of dnIKK2 inhibits NF-κB activation

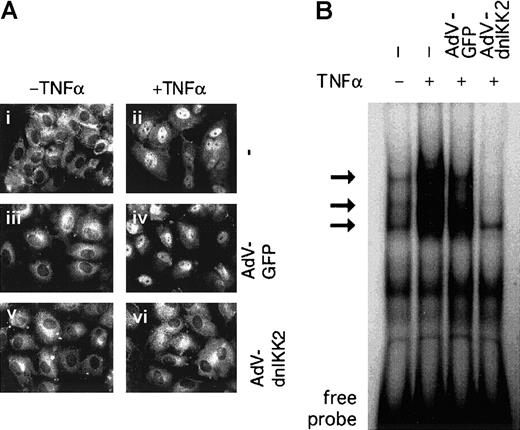

The activation of NF-κB is mainly controlled by translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, resulting in binding of the transcription factor to its DNA binding site(s). We have, therefore, first analyzed dnIKK2-expressing HUVECs by immunostaining with an anti-p65 antibody (Figure 2A). p65–NF-κB was located in the cytoplasm in unstimulated HUVECs but translocated to the nucleus within 1 hour after stimulation both in control (AdV-GFP) or transduced cells. In contrast, in dnIKK2-expressing HUVECs, NF-κB remained in the cytoplasm even after stimulation. Second, DNA binding activity of NF-κB was analyzed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (Figure 2B). Whereas nuclear extracts from noninfected, as well as control virus-infected cells showed strong inducible activity of NF-κB, no detectable binding of the transcription factor was observed in AdV-dnIKK2–infected and –stimulated cells.

Activation of NF-κB is inhibited in dnIKK2-expressing cells.

(A) Nuclear translocation of p65–NF-κB. Control HUVECs (i-ii) or HUVECs that had been transduced with control virus (iii-iv) or AdV-dnIKK2 (v-vi) were stimulated with TNFα for 1 hour (ii,iv,vi) or left unstimulated (i,iii,v). Nuclear translocation of NF-κB was revealed by immunofluorescence, using an anti-p65 antibody. (B) Nuclear extracts were prepared from control cells, AdV-GFP, and from AdV-dnIKK2–transduced HUVECs and were analyzed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay. The NF-κB–specific bands are indicated by arrows.

Activation of NF-κB is inhibited in dnIKK2-expressing cells.

(A) Nuclear translocation of p65–NF-κB. Control HUVECs (i-ii) or HUVECs that had been transduced with control virus (iii-iv) or AdV-dnIKK2 (v-vi) were stimulated with TNFα for 1 hour (ii,iv,vi) or left unstimulated (i,iii,v). Nuclear translocation of NF-κB was revealed by immunofluorescence, using an anti-p65 antibody. (B) Nuclear extracts were prepared from control cells, AdV-GFP, and from AdV-dnIKK2–transduced HUVECs and were analyzed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay. The NF-κB–specific bands are indicated by arrows.

dnIKK2 prevents expression of inflammatory markers and leukocyte adhesion

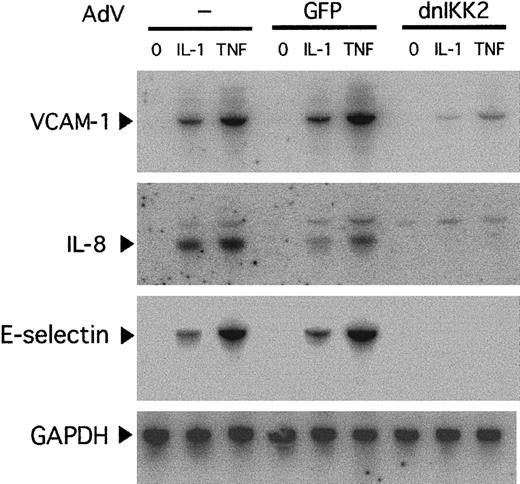

Because several genes that are characteristic for the inflammatory response in ECs contain functional NF-κB binding sites in their promoter regions,3 we first analyzed messenger RNA (mRNA) levels of some of them by Northern blotting in nonstimulated or stimulated, either noninfected, AdV-dnIKK2–infected, or control virus–infected ECs. VCAM-1, IL-8, and E-selectin mRNAs were inducible in noninfected and control virus–infected HUVECs but showed strong reduction of their steady-state levels in AdV-dnIKK2–infected cells (Figure 3). In contrast to IL-8 and E-selectin, small amounts of VCAM-1 mRNA were detected in stimulated dnIKK2-expressing cells. This may indicate that other signaling pathways or transcription factors distinct from NF-κB might be responsible for a small part of VCAM-1 expression.

Northern blot analysis of inflammatory markers.

HUVECs were transduced with AdV-dnIKK2 or control virus (AdV-GFP) or left without virus and after 2 days stimulated with IL-1 or TNFα for 4 hours as indicated. VCAM-1–, IL-8–, and E-selectin–specific bands are indicated. Equivalent loading and transfer of RNA was confirmed by hybridization with GAPDH.

Northern blot analysis of inflammatory markers.

HUVECs were transduced with AdV-dnIKK2 or control virus (AdV-GFP) or left without virus and after 2 days stimulated with IL-1 or TNFα for 4 hours as indicated. VCAM-1–, IL-8–, and E-selectin–specific bands are indicated. Equivalent loading and transfer of RNA was confirmed by hybridization with GAPDH.

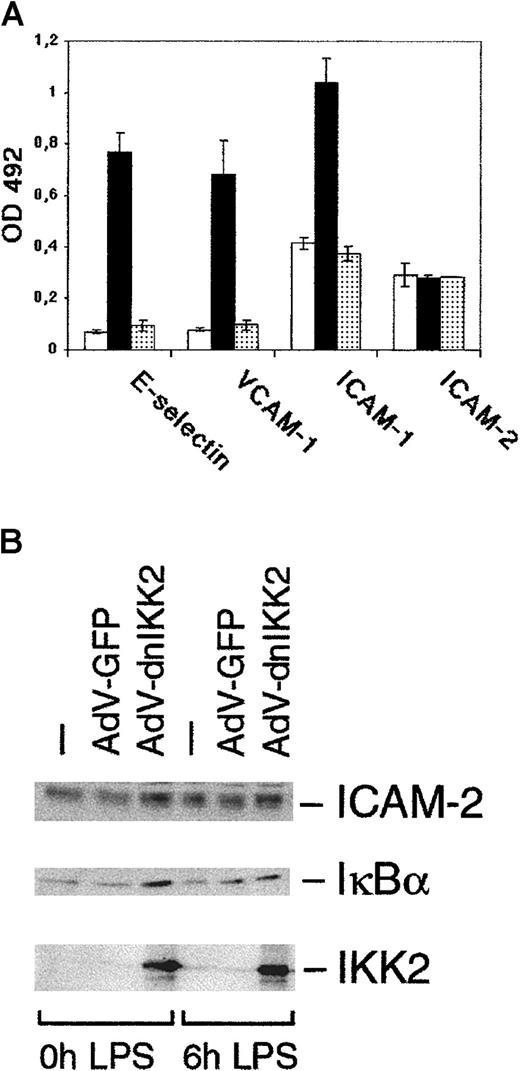

Next, we determined protein expression of cell adhesion molecules (E-selectin, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1), using a cell ELISA. The inhibitory effect of dnIKK2 on VCAM-1 and E-selectin mRNAs was reflected on the protein level. ICAM-1 expression was reduced to basal levels as well (Figure 4A). Interestingly, the higher basal expression levels of ICAM-1, which are in accordance with published observations, were not affected by dnIKK2, suggesting that the constitutive part of ICAM-1 expression occurs independently of NF-κB. As a control, we also determined expression of ICAM-2, a constitutively expressed gene. Both in the cell ELISA (Figure 4A) and in the Western blot (Figure 4B), ICAM-2 expression was not affected by AdV-dnIKK2. Because IκBα is the direct target of IKK2 and is also (re)expressed in a NF-κB–dependent manner following degradation,29 we have analyzed IκBα levels in dnIKK2-expressing cells. As shown by Western blot (Figure 4B), IκBα expression was not diminished in the presence of dnIKK2 on stimulation. In contrast, amounts even appeared to be slightly increased, indicating that dnIKK2 successfully inhibited degradation and possibly stabilized IκBα protein.

DnIKK2 inhibits the expression of cell adhesion molecules.

(A) AdV-dnIKK2–transduced (░), AdV-GFP–transduced (▪), or control (■) HUVECs were seeded in 96-well plates. AdV-dn IKK2– and AdV-GFP–transduced cells were stimulated with LPS for 6 hours and control HUVECs were left unstimulated; cells were then analyzed for expression of E-selectin, ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and ICAM-2 using a cell ELISA as described in “Materials and methods.” (B) Western blot analysis of dnIKK2, GFP-expressing, or control HUVECs. Two days after transduction with the respective viruses, cells were stimulated with LPS for 6 hours as indicated and extracts analyzed for expression of ICAM-2, IκBα, and (dn)IKK2. IKK2 was detected with an anti-IKK2 antibody to allow comparison of the levels of transfected and endogenous IKK2.

DnIKK2 inhibits the expression of cell adhesion molecules.

(A) AdV-dnIKK2–transduced (░), AdV-GFP–transduced (▪), or control (■) HUVECs were seeded in 96-well plates. AdV-dn IKK2– and AdV-GFP–transduced cells were stimulated with LPS for 6 hours and control HUVECs were left unstimulated; cells were then analyzed for expression of E-selectin, ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and ICAM-2 using a cell ELISA as described in “Materials and methods.” (B) Western blot analysis of dnIKK2, GFP-expressing, or control HUVECs. Two days after transduction with the respective viruses, cells were stimulated with LPS for 6 hours as indicated and extracts analyzed for expression of ICAM-2, IκBα, and (dn)IKK2. IKK2 was detected with an anti-IKK2 antibody to allow comparison of the levels of transfected and endogenous IKK2.

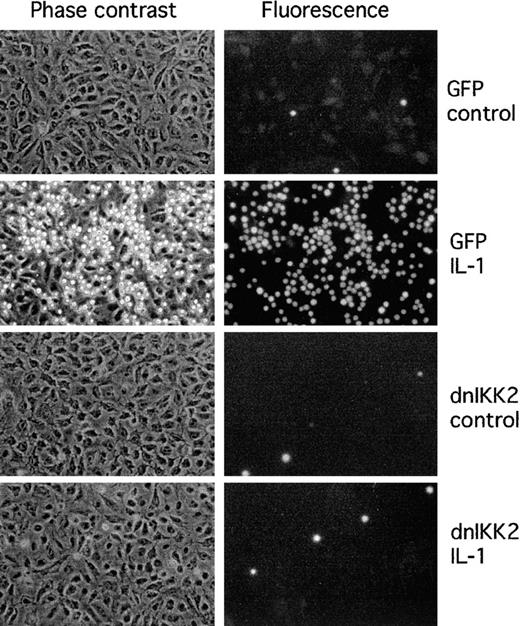

The functional consequences of inhibition of cell adhesion molecule expression are shown in a cell adhesion assay. Binding of human promyelocytic HL-60 cells to activated dnIKK2-expressing HUVECs was strongly inhibited (Figure 5). No major effect of the control virus in comparison to nontransduced cells was observed.

Adhesion of HL-60 cells to HUVECs is inhibited by expression of dnIKK2.

HUVECs were transduced with AdV-dnIKK2 (dnIKK2) or control virus (GFP) as indicated and 3 days later stimulated with IL-1 for 4 hours. Adhered CMFDA-labeled HL-60 cells were viewed in phase contrast (left row) and under the fluorescence microscope in the FITC channel (right row).

Adhesion of HL-60 cells to HUVECs is inhibited by expression of dnIKK2.

HUVECs were transduced with AdV-dnIKK2 (dnIKK2) or control virus (GFP) as indicated and 3 days later stimulated with IL-1 for 4 hours. Adhered CMFDA-labeled HL-60 cells were viewed in phase contrast (left row) and under the fluorescence microscope in the FITC channel (right row).

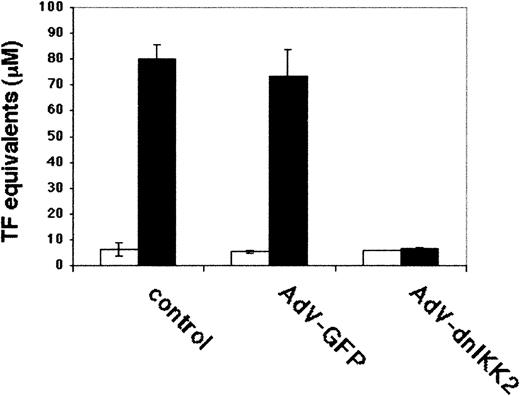

Inhibition of coagulation and capillary tube formation in dnIKK2-expressing cells

We have performed functional assays to test the effect of dnIKK2 overexpression on 2 other important properties of ECs. With the use of a clotting assay as read-out for tissue factor expression, virtually complete inhibition of procoagulant activity was observed in dnIKK2-expressing cells (Figure 6).

Measurement of procoagulant activity.

DnIKK2-expressing, GFP-expressing, or control HUVECs were assayed for LPS-induced tissue factor activity, using a clotting assay. Time until clot formation was transformed into thromboplastin units, using a standard curve. ▪, LPS; ■, uninduced. Values are from triplicate experiments.

Measurement of procoagulant activity.

DnIKK2-expressing, GFP-expressing, or control HUVECs were assayed for LPS-induced tissue factor activity, using a clotting assay. Time until clot formation was transformed into thromboplastin units, using a standard curve. ▪, LPS; ■, uninduced. Values are from triplicate experiments.

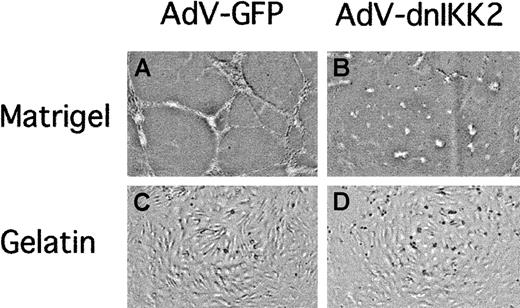

In the adult organism, neoangiogenesis occurs mainly during wound healing or in the female reproductive cycle. Moreover, the formation of new capillaries is a prerequisite for the growth of solid tumors. We, therefore, investigated the effect of dnIKK2 overexpression on capillary tube formation in a matrigel-based assay system,28 one of several assays that have been developed to study angiogenesis in vitro. EC-expressing dnIKK2 was unable to form tubelike structures, whereas cells transduced with the control virus (AdV-GFP) retained this ability (Figure7). Inhibition of tube formation was not due to decreased viability of adenovirus-transduced cells, because they adopted a normal cobblestonelike morphology when plated on gelatin.

Expression of dnIKK2 inhibits capillary tube formation.

HUVECs were transduced with either the control virus AdV-GFP (A,C) or with AdV-dnIKK2 (B,D) and after 2 days plated on matrigel (A-B) or gelatin (C-D) as indicated. Pictures were taken 16 hours after plating.

Expression of dnIKK2 inhibits capillary tube formation.

HUVECs were transduced with either the control virus AdV-GFP (A,C) or with AdV-dnIKK2 (B,D) and after 2 days plated on matrigel (A-B) or gelatin (C-D) as indicated. Pictures were taken 16 hours after plating.

Discussion

Under physiologic conditions, the endothelium functions to supply nutrients, oxygen, and macromolecules to the underlying tissue and to maintain an anticoagulant surface that ensures unobstructed blood flow. However, this situation changes dramatically during inflammation: ECs diminish their barrier function resulting in increased passage of electrolytes and express chemokines and cell adhesion molecules that lead to the attraction and transmigration of cells of the immune system to fight bacterial or viral infections.30 In a variety of diseases, this beneficial response of the immune system may be exaggerated and, because of the expression of inflammatory mediators, drive the endothelium into a vicious circle of stimulation and restimulation that results in tissue damage and impaired vascular function.

The complexity of this response is executed mostly by de novo expression of genes, the vast majority of which, especially on inflammatory challenge, appears to be regulated by NF-κB.31 However, most studies have used transient transfections of reporter genes for the analysis of the respective promoters or low molecular weight inhibitors to demonstrate their NF-κB dependence.32-35 Whereas reporter gene studies may not reflect the behavior of the endogenous genes, presently available NF-κB inhibitors, such as antioxidants, radical scavengers, or proteasome inhibitors, often lack specificity.36 37 We have, therefore, used a highly specific genetic approach of NF-κB inhibition by using a recombinant adenoviral vector to study the expression of endogenous genes as well as selected functional parameters of endothelial cells.

From the point of both efficiency and specificity, IKK2 appears to be an ideal target for inhibition of NF-κB. It is part of the IκB kinase complex that directly phosphorylates IκBα on the aminoterminal serine residues, a key regulatory signal for the ubiquitination-dependent proteolytic degradation of IκBα that results in liberation of NF-κB from the inactive cytoplasmic complex and its translocation to the nucleus. In transient transfections, dnIKK2 but not dnIKK1 was shown to inhibit signals generated by inflammatory cytokines or LPS8; moreover, no crosstalk with other signaling pathways has been reported on the level of the IKKs. Genetic data from IKK2 knock-out mice revealed that IKK2−/− mice display a very similar phenotype as RelA (p65–NF-κB)-deficient animals, which is embryonic lethality at day 13.5.38,39 Because of this phenotype, the role of IKK2 in ECs has not been studied, but it indicates that deletion of IKK2 strongly impairs NF-κB function. In contrast, IKK1−/− mice present with skin and limb abnormalities but show normal NF-κB activation,40 41suggesting that IKK1 is dispensable for cytokine-stimulated NF-κB activation.

We show that ectopic expression of a kinase-inactive mutant of IKK2 (dnIKK2) resulted in impaired nuclear translocation of p65–NF-κB and in strong reduction of nuclear DNA binding of the transcription factor in stimulated HUVECs. Consecutively, we performed a series of analyses to determine the effect of dnIKK2 on 3 major functions of the endothelium, namely inflammation, coagulation, and angiogenesis.

As the inflammatory response in ECs is characterized by the transient expression of chemokines and cell adhesion molecules that serve as chemoattractants and docking molecules, respectively, for cells of the immune system, we have analyzed the expression of some of these markers on the mRNA, protein, and functional level. In Northern blots, expression of IL-8, VCAM-1, and E-selectin were reduced to basal levels in dnIKK2-expressing cells. Likewise, on the protein level, the inducible expression of the cell adhesion molecules VCAM-1 and E-selectin was strongly decreased. Expression of ICAM-1, which shows a higher constitutive expression on HUVECs, was reduced to its preactivation level as well, indicating that this constitutive part of ICAM-1 expression occurs independently of NF-κB. In contrast, levels of ICAM-2 that is constitutively expressed on ECs remained largely unchanged. IκBα, which is an NF-κB–dependent gene29and whose protein levels may, therefore, be expected to be down-regulated in dnIKK2-expressing cells, appeared to be even higher, possibly due to a stabilizing effect of dnIKK2. The functional consequences of the lack of cell adhesion molecule expression were reflected in a cell adhesion assay: HL-60 cells showed complete lack of adhesion to cytokine-stimulated HUVECs that expressed dnIKK2.

The regulation of procoagulant properties is central to the function of the endothelium. One of the key regulatory molecules in this regard, tissue factor, has been shown to contain NF-κB regulatory element(s) in its promoter region, along with other transcription factor binding sites, such as SP-1 and Egr-1.42 43 Tissue factor is expressed on the EC surface in response to cytokines (IL-1, TNFα) or LPS. Expression of dnIKK2 inhibited clot formation in LPS-stimulated HUVECs, demonstrating that inhibition of NF-κB is sufficient to prevent hemostasis in this coagulation assay.

The process of angiogenesis involves multiple steps, including EC proliferation and migration. Although the involvement of NF-κB in angiogenesis has not been studied in detail, several lines of evidence suggest a functional role for this transcription factor: NF-κB was found to be necessary for capillary tube formation in vitro and in a retinal neovascularization model in mice.44,45Furthermore, inhibition of NF-κB by antisense oligonucleotides blocked capillary tube formation in collagen gels.46Possible mechanisms include the inhibition of NF-κB–dependent IL-8 expression as well as inhibition of survival signals that are normally elicited through αvβ3 integrin engagement.44,46 In addition, the induction of matrix metalloproteinases and of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor flk-1 has been shown to be NF-κB dependent.47 In our in vitro model of angiogenesis, a matrigel assay, HUVECs expressing dnIKK2 but not cells transduced with a control virus showed a strongly reduced ability to form capillary tubelike structures. Although these experiments do not allow us to determine which step in this in vitro angiogenesis model is dependent on NF-κB, they substantiate earlier findings on the involvement of NF-κB, using a specific genetic inhibitor.

Thus, it appears that in ECs NF-κB is crucially involved not only in inflammatory reactions but also in aspects of coagulation and (neo)angiogenesis. A common denominator of these functions is their requirement in situations of attack or injury of an organism by exogenous challenges. They may, therefore, be summarized as reactions of defense and repair. The activation of NF-κB is, thereby, consistent with its role as a stress response factor. Apart from certain developmental functions, it is up-regulated only on demand to govern the organism's response and afterward returns to preactivation levels.48 Pharmacologic or genetic inhibition of NF-κB may thus offer the possibility to modulate overshooting reactions, such as chronic inflammation, or detrimental processes, such as tumor angiogenesis.

The authors wish to thank Michaela Kind and Sonja Novak for excellent technical assistance, Diana Undeutsch for help with the manuscript, and the members of our department for valuable discussion.

Supported by research grants SFB 05-08 and SFT 05-12 from the Austrian Science Foundation and grant 6912 from the Austrian Nationalbank.

W.O. and R.H.-W. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Rainer de Martin, Department of Vascular Biology and Thrombosis Research, University of Vienna, Vienna International Research Cooperation Center (VIRCC), Brunnerstr. 59, A-1235 Vienna, Austria; e-mail: rainer.de.martin@univie.ac.at.