Abstract

This study examined the influence of the PlApolymorphism of glycoprotein IIIa (GPIIIa) in determining the response to an oral GPIIb/IIIa antagonist, orbofiban, in patients with unstable coronary syndromes. Genotyping for the PlA polymorphism was performed in 1014 patients recruited into the OPUS-TIMI-16 (orbofiban in patients with unstable coronary syndromes–thrombolysis in myocardial infarction 16) trial, in which patients were randomized to low- or high-dose orbofiban or placebo for 1 year. The primary end point (n = 165) was a composite of death, myocardial infarction (MI), recurrent ischemia requiring rehospitalization, urgent revascularization, and stroke. Overall, orbofiban failed to reduce ischemic events when compared with placebo, but increased the rate of bleeding. In the whole population, PlA2 carriers had a significant increase in MI (n = 33) during follow up, with a relative risk (RR) of 2.71 (95% CI, 1.37 to 5.38; P = .004). There was a significant interaction between treatment (placebo and orbofiban) and the PlA polymorphism for bleeding (n = 187; P = .05). Thus, while orbofiban increased bleeding in noncarriers (RR = 1.87, 1.29 to 2.71;P < .001) in a dose-dependent fashion, it did not increase bleeding events in PlA2 carriers (RR = 0.87, 0.46 to 1.64). There was no interaction between treatment (placebo and orbofiban) and the PlA polymorphism for the primary end point (P = .10). However, in the patients receiving orbifiban there was a higher risk of a primary event (RR = 1.55, 1.03 to 2.34; P = .04) and MI (RR 4.27, 1.82 to 10.03;P < .001) in PlA2 carriers compared with noncarriers. In contrast, there was no evidence that PlA2influenced the rate of recurrent events in placebo-treated patients. In patients presenting with an acute coronary syndrome, the PlA polymorphism of GPIIb/IIIa may explain some of the variance in the response to an oral GPIIb/IIIa antagonist.

Introduction

Platelet activation and subsequent aggregation play major roles in initiating coronary thrombosis, the underlying event in acute coronary syndromes such as unstable angina and myocardial infarction (MI). Platelet aggregation is mediated by glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa, the receptor for fibrinogen and von Willebrand factor (vWf). GPIIb/IIIa antagonists bind to the receptor and prevent platelet aggregation to all known agonists. Yet oral GPIIb/IIIa antagonists have proven ineffective and may be harmful when administered chronically to patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes.1 Three large-scale clinical trials have reported an increase in death and MI in patients on active treatment compared with placebo. In the OPUS-TIMI-16 (orbofiban in patients with unstable coronary syndromes–thrombolysis in myocardial infarction 16) trial of orbofiban, the study was terminated due to an increase in mortality.2 In the SYMPHONY II (sibrafiban versus aspirin to yield maximum protection from ischemic heart events post–acute coronary syndromes II) trial,3 there was an increase in MI and death in patients on sibrafiban.

Genetic factors are postulated to modulate drug response, either in determining efficacy or the risk of side effects. Intuitively, this is most likely where the genetic variation influences the drug target or enzymes responsible for drug metabolism. In this study, we examined the influence of the PlA polymorphism of GPIIIa on the response to the GPIIb/IIIa antagonist, orbofiban, in patients with unstable coronary syndromes.2 About 20% of the population are carriers of the PlA2 polymorphism, which results in a proline in place of a leucine at position 33 of GPIIIa.4PlA2 has been associated with MI, coronary thrombosis, and restenosis following coronary angioplasty and with stroke.5-11 However, many studies have failed to confirm any link between the PlA mutation and cardiovascular disease.12-14 It is also unclear whether the PlA2 variant alters receptor function. Several studies have shown enhanced fibrinogen binding to and aggregation of platelets from individuals either heterozygous or homozygous for PlA2.15-17 The PlA2 receptor also exhibits enhanced “outside-in” signaling when expressed in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells.18 Finally, carriers of PlA2 receiving aspirin have a blunted bleeding time response.19 However, other studies have failed to show any enhanced effect.20-22

Patients, materials, and methods

Study population

The analysis was a substudy of OPUS-TIMI-16, a phase III multicenter, double-blind, and placebo-controlled trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of orbofiban, a GPIIb/IIIa antagonist, in patients with unstable coronary syndromes.2 Between October 1997 and November 1998, 10 288 patients were recruited from 888 hospitals in 29 countries. Of these, 1023 provided separate written, informed consent for genetic analysis and 1014 provided samples. Consent was obtained after randomization for analysis of genetic variation in relation to cardiovascular disease and therapy, with analysis performed on a database free of patient identifiers to protect anonymity. Patients who withdrew from the study prior to genetics sampling were not required to return to the clinic, and were therefore not sampled.

The protocol for the main study has been outlined in detail elsewhere.2 Briefly, the inclusion criteria were ischemic discomfort at rest for at least 5 minutes within the previous 72 hours with one of the following: (1) new or presumably new electrocardiographic changes (ST segment deviation ≥ 0.5 mm, T-wave inversion ≥ 3 mm in at least 3 contiguous leads, or left bundle branch block); (2) positive serum markers; (3) history of MI, angioplasty, bypass surgery, or coronary stenosis ≥ 50%; (4) age ≥ 65 years and a history of angina or positive stress test; (5) prior transient ischemic attack or nonhemorrhagic stroke; (6) peripheral vascular disease; or (7) diabetes mellitus.

Trial design

All patients received 150 to 162 mg aspirin daily and were randomized to one of 3 groups: (1) 50 mg orbofiban twice daily for 30 days, followed by 30 mg twice daily (n = 353) (denoted the 50mg/30mg group); (2) 50 mg orbofiban twice daily for 30 days, followed by 50 mg twice daily (n = 308) (denoted the 50mg/50mg group); (3) placebo (n = 353).

After randomization, patients received the drug as soon as possible, but within 72 hours of the index event. Treatment was to continue for a minimum of 6 months, and up to 24 months. The actual treatment period ranged from 1 month to a maximum of approximately 15 months.

The primary end point was a composite of death, MI, recurrent ischemia at rest leading to rehospitalization or urgent revascularization, or stroke. A clinical events committee adjudicated all end points. Additional analyses were performed for MI and for all recorded coronary ischemic events. Severe or life-threatening bleeding was defined as an intracranial hemorrhage or bleeding associated with severe hemodynamic compromise; major bleeding was that associated with >15% absolute reduction in hematocrit or requiring a blood transfusion; minor bleeding was (nonmajor) bleeding that required medical treatment or laboratory evaluation.2

Genetic analysis

Genetic analysis was performed at a mean of 157 days in 1014 patients, the majority of whom were from the USA (n = 537) and Canada (n = 276). Fifty-nine percent of the patients presented with acute MI as their index event and the remainder presented with unstable angina. Following DNA extraction,23 the PlApolymorphism was detected by capillary electrophoresis, as previously described.24

Statistical analyses

Means and proportions were compared using a t test or chi-square as appropriate. Survival analyses considered the time to the first primary end-point event, and also the time to the first severe, major, or minor bleeding event. All times were measured from the day of randomization. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. A Cox proportional hazards analysis was used when adjusting for the possible confounding effects of other prognostic factors. The nominal significance level of 0.05 was reduced to 0.025 for comparisons between each dose and placebo. Tests of interaction between genotype and treatment were performed by fitting terms within the survival analysis for genotype and treatment, and an interaction term. The P value of the interaction term was then calculated to interpret significance.

Sixty-four patients were removed from the study due to poor health or due to the wishes of the patient or medical provider. Fifty of those removed had not had a previous primary event. A Cox proportional hazards analysis assumes that censoring is noninformative. Clearly this is not the case for those removed prior to their first event. To assess how sensitive our conclusions were to those patients lost to follow-up, we performed an analysis where we considered all those patients lost to follow-up as censored event-free and then repeated the analysis assuming that observations on those lost to follow-up were complete and represented time to first event. The results were comparable, so we report only the first analysis.

Results

Among the 1014 patients for whom genetic material was available (Table 1), primary end-point events were recorded in 165 patients. Of these patients, 33 had a recurrent MI, 55 underwent urgent revascularization, and 72 were rehospitalized for recurrent ischemia. Six patients experienced a stroke and there were 3 deaths. Bleeding occurred in 187 patients.

In studying effects of both treatment and genotype in a population, it is important to consider possible interactions between genotype and treatment. In the absence of an interaction between genotype and treatment, analysis of independent effects are appropriate. However, when there is evidence of an interaction, subpopulations should be analyzed separately. For this reason, we present first the independent genotypic effects, and then consider possible interactions, presenting genotypic effects in treated and untreated subpopulations.

Prevalence of the PlA polymorphism

The frequency of the PlA2 allele in all 1014 patients was similar to that found in several previous studies,14,15 although lower than the 50% reported in young patients with acute MI.6 The frequencies of the PlA1 and the PlA2 allele were 0.86 and 0.14, respectively. Thus, 26.3% of patients carried at least one PlA2 allele and 2.2% of patients were homozygous for PlA.2 The PlA2 allele was evenly distributed among the racial groups (data not shown). A higher proportion of the PlA2 carriers were male (80.5% vs 73.8% for noncarriers; P = .03). PlA2 carrier frequency varied between countries (P = .03), with the most notable difference between Canadian (21.9% of 265 patients) and US Caucasians (30.0% of 477 patients). Among the 30 blacks in the study, the PlA2 frequency was similar to that of Caucasians (18.3%).

Primary end point and MI: genotypic effects

The median follow-up time for patients without a primary end point was 203 days with lower and upper quartiles of 150 and 303 days, respectively. There were 165 patients (16.5%) who had a primary event. This is lower than the 22.9% observed in the overall study of 10 288 patients followed to 10 months,2 possibly as the subpopulation studied had a lower risk profile, being younger and less often diabetic. Alternatively, some patients with serious events may have been removed from the study prior to genetic sampling.

The time to first primary event was analyzed using a proportional hazards model, which adjusted for age and sex. Considering the total population, there was no significant association between PlA carrier status and the risk of a primary event (relative risk [RR], 1.26; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.91 to 1.76; P = .17). However, the rate of MI was significantly higher among PlA2 carriers (RR = 2.71; 95% CI, 1.37 to 5.38; P = .004). This remained true even after adjusting for possible confounding effects of treatment, country of origin, and/or race. The risk of a primary end-point event increased slightly with the number of PlA alleles carried: 15.4% of PlA1/PlA1 patients had events, compared with 18.4% of the 245 PlA1/PlA2 heterozygotes and 22.7% of the 22 PlA2/PlA2 genotypes, although this trend was not statistically significant.

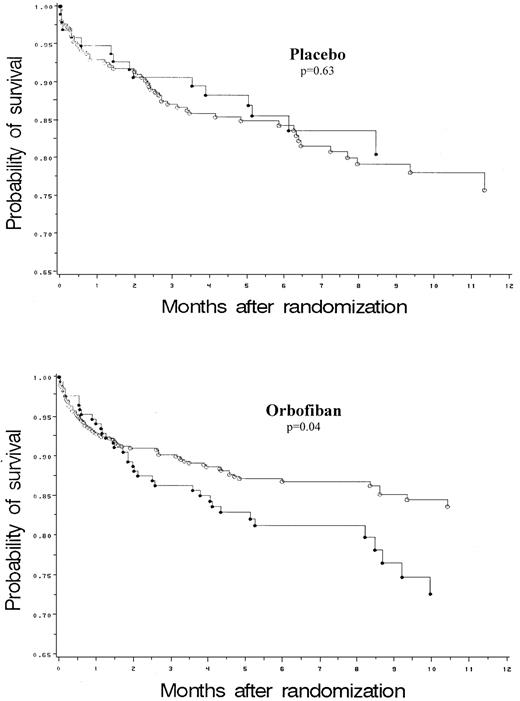

Interaction between the PlA polymorphism and treatment: primary end point and MI

Overall, treatment with orbofiban did not affect the primary end point or the rate of MI irrespective of the genotype (Tables2 and 3). The interaction between the effects of genotype and treatment (Tables 3and 4) approached significance for the primary end point (P = .10) and for MI (P = .08). The RR of a primary end-point event on orbofiban compared with placebo among PlA2 carriers was 1.37 (95% CI, 0.75 to 2.51) (Table 3), and among noncarriers RR was 0.73, (95% CI, 0.51 to 1.06) (Figure 1). Although among PlA2 carriers on orbofiban there was a trend toward a higher RR (2.46) of MI (95% CI, 0.70 to 8.67) (Table 3), this did not achieve statistical significance. In addition to examining the effect of treatment (placebo and orbofiban), we also examined the genotypic effects separately in the placebo and active treatment arms. When PlA2 carriers and PlA2 noncarriers were compared while on orbofiban, PlA2 carriers had an RR of a primary event of 1.55 (95% CI, 1.03 to 2.34, P = .04) (Table 4). In contrast, the primary event rate was not influenced by genotype in patients on placebo. There was also a significantly higher risk of MI in PlA2 carriers on active orbofiban, but not in those on placebo (Table 4).

Kaplan-Meier estimates of the primary event survival for PlA2 carriers (●) and noncarriers (○) on placebo and orbofiban.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of the primary event survival for PlA2 carriers (●) and noncarriers (○) on placebo and orbofiban.

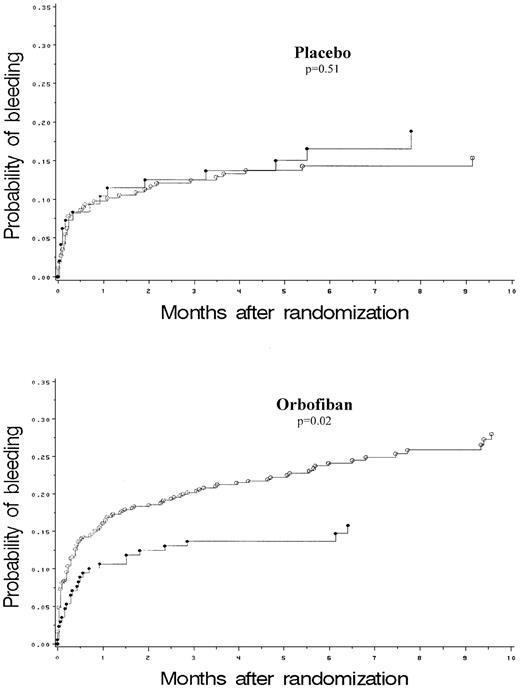

Interaction between the PlA polymorphism and treatment: bleeding

Severe, major, recurrent, or minor bleeding occurred in 18.4% of patients during the study (Tables 2 and 3). For the total cohort studied, bleeding was increased with orbofiban relative to placebo (P < .002). A Cox analysis of the time to first bleeding was performed, adjusting for age and sex and stratified by country (Table 3). The risk of bleeding relative to placebo (RR and 95% CI) was 1.35 (0.94 to 1.93) and 1.88 (1.33 to 2.67) for the low dose and high dose orbofiban groups, respectively. The interaction between genotype and treatment (placebo and orbofiban) on the risk of bleeding was significant. Thus, while there was a highly significant, dose-dependent increase in bleeding events in PlA1homozygous patients, there was no increase in PlA2 carriers (Table 3, Figure 2). As with the efficacy end points, we also examined the genotypic effects separately in the placebo and active treatment arms. When PlA2 carriers and PlA2 noncarriers while on orbofiban were compared, the risk of bleeding was lower for PlA2 carriers relative to PlA2 noncarriers (RR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.39 to 0.92;P = .02, Table 4). PlA2 carriers were protected against bleeding most clearly in the high dose group, since their bleeding rate was no higher than that of placebo, whereas PlA1/A1 homozygotes had a large increase in bleeding risk (Table 2). The results may be explained by a partial agonist effect of the drug in carriers of PlA2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of the probability of bleeding for PlA2 carriers (●) and noncarriers (○) on placebo and orbofiban.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of the probability of bleeding for PlA2 carriers (●) and noncarriers (○) on placebo and orbofiban.

Discussion

Previous studies have implicated PlA2 in acute MI, even among patients who are heterozygous for the mutation.5-10 This might be expected if the mutation enhanced the function of the receptor and indeed several studies demonstrate a modest increase in platelet activity as a consequence of the PlA polymorphism.15-19 Thus, there is an increase in fibrinogen binding to platelets of patients homozygous for the PlA2 allele and enhanced platelet aggregation to low concentrations of agonists.15-17 PlA2 carriers are also reported to have increased thrombin generation when on aspirin compared with noncarriers.25 However, other studies have failed to show any functional effect of the PlA2polymorphism.20-22

In this substudy of the OPUS trial of orbofiban, the frequency of the PlA2 allele was no higher in patients presenting with an unstable coronary syndrome compared with that reported by several investigators in stable coronary syndromes or noncardiac patients.14,16 Moreover, there was no association between the PlA polymorphism and the subsequent occurrence of the primary end point of the study, a composite of death, MI, recurrent ischemia at rest leading to rehospitalization or urgent revascularization, or stroke. However, of these only MI has been consistently linked to coronary thrombosis and our data demonstrated an association between the PlA polymorphism and subsequent MI. In previous studies,5 9 PlA2 has shown an interaction with age (an increased risk of developing MI at a young age) and smoking. We found no significant interaction with age, although the combination of the PlA2 allele and smoking or diabetes mellitus was weakly associated with an increased event rate (data not shown).

The underlying hypothesis for the study was that the PlAgenotype would influence the response to a GPIIb/IIIa antagonist. Orbofiban had no significant impact on the frequency of primary events in the subset of patients studied. Although the overall interaction of genotype with treatment was not quite significant, among patients on active treatment there was an increase in events among PlA2carriers that was particularly striking for MI, with an RR of 4.27. In contrast, within the placebo group PlA2 carriers were not at a higher risk. The results of the analyses for bleeding and for MI are internally consistent and suggest that at the very least the PlA2 variant blunts response to treatment. The results are also consistent with the hypothesis that PlA2 is a prothrombotic variant, increasing events and reducing bleeding, although in this study such effects are absent in the placebo arm and only observed in the treated groups.

The OPUS-TIMI-16 trial showed an increase in death that was evident in both active treatment arms.2 Subsequent analysis has shown that many of the deaths reflected new coronary events. Two other large-scale clinical trials of oral GPIIb/IIIa antagonists in patients with unstable coronary syndromes confirm these findings (SYMPHONY I and II).3 Our study shows that it is possible that the increase in coronary events occurs largely in PlA2carriers. Why oral GPIIb/IIIa antagonists increase cardiac events is unknown. GPIIb/IIIa is not a passive receptor, but upon fibrinogen binding it transmits signals that amplify platelet activation, so-called “outside-in” signaling. This signaling is critical for platelet activity, as defects in outside-in signaling prevent platelets from aggregating despite fibrinogen binding.26

There is evidence that GPIIb/IIIa antagonists may also trigger outside-in signaling and so act as partial agonists.27,28Thus, increased platelet activity, detected as expression of CD62 (P selectin), has been reported in patients on orbofiban.29,30 Compared with the PlA1variant, the PlA2 variant of GPIIb/IIIa exhibits greater outside-in signaling detected as phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase when cells expressing the mutated receptor are exposed to fibrinogen.18 Whether the PlA2 variant of GPIIb/IIIa is also more susceptible to the partial agonist activityinduced by smaller ligands, such as GPIIb/IIIa antagonists, and whether this explains why the response to GPIIb/IIIa antagonists is modified in patients carrying the variant, has yet to be addressed. It is worth noting that primary events and MI were more common at the low dose of orbofiban (Table 3), where partial agonism would be more evident.

In conclusion, the PlA genotype may modify the response to an oral GPIIb/IIIa antagonist and may in part explain the variance in the response to these drugs in humans. Whether this applies also to short-term intravenous administration of this class of drugs is as yet unknown.

We thank the OPUS-TIMI-16 investigators for their immense effort in the collection of the clinical data and blood samples for DNA used in this study.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Desmond J. Fitzgerald, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, 123 St Stephen's Green, Dublin 2, Ireland; e-mail: dfitzgerald@rcsi.ie.