Abstract

Many malignancies of mature B cells are characterized by chromosomal translocations involving the immunoglobulin heavy chain(IGH) locus on chromosome 14q32.3 and result in deregulated expression of the translocated oncogene. t(2;14)(p13;q32.3) is a rare event in B-cell malignancies. In contrast, gains and amplifications of the same region of chromosome 2p13 have been reported in 20% of extranodal B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas (B-NHL), in follicular and mediastinal B-NHL, and in Hodgkin disease (HD). It has been suggested that REL, an NF-κB gene family member, mapping within the amplified region, is the pathologic target. However, by molecular cloning of t(2;14)(p13;q32.3) from 3 cases of aggressive B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)/immunocytoma, this study has shown clustered breakpoints on chromosome 2p13 immediately upstream of a CpG island located about 300 kb telomeric of REL. This CpG island was associated with a Krüppel zinc finger gene (BCL11A), which is normally expressed at high levels only in fetal brain and in germinal center B-cells. There were 3 major RNA isoforms ofBCL11A, differing in the number of carboxy-terminal zinc fingers. All 3 RNA isoforms were deregulated as a consequence of t(2;14)(p13;q32.3). BCL11A was highly conserved, being 95% identical to mouse, chicken, and Xenopus homologues.BCL11A was also highly homologous to another gene(BCL11B) on chromosome 14q32.1. BCL11Acoamplified with REL in B-NHL cases and HD lymphoma cell lines with gains and amplifications of 2p13, suggesting thatBCL11A may be involved in lymphoid malignancies through either chromosomal translocation or amplification.

Introduction

Many subtypes of malignancy are associated with specific chromosomal translocations, which play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of disease. In the leukemias and lymphomas of mature B-cells, these frequently involve the immunoglobulin (IG)loci and result in deregulated expression of the translocated oncogene, due, in part, to the presence of potent B cell–specific transcriptional enhancers within the IG loci.1All the common IG translocations have been cloned. Paradigms include the deregulation of cyclin D1 by t(11;14)(q13;q32.3), found in all cases of mantle cell lymphoma; BCL2 by t(14;18)(q32.3;q21.3), found in 80% of follicular lymphoma; andMYC by t(8;14)(q24.1;q32.3) and variant translocations in all cases of Burkitt lymphoma.1

On the basis of cytogenetics alone, several rare, but nonetheless recurrent IG translocations remain to be cloned, principally in aggressive large-cell B-NHL2; their molecular cloning continues to allow the isolation of novel dominant oncogenes and to define new pathogenic mechanisms.1,3-6 Chromosomal translocation t(2;14)(p13;q32.3) is one example and has been reported in a variety of B-cell malignancies ranging from B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia to myeloma. This translocation is frequently the sole cytogenetic abnormality within the neoplastic clone (Watson et al,7 Geisler et al,8 Sonoki et al,9 and http://cgap.nci.nih.gov/Chromosomes/Mitelman). We report here the recurrent involvement and deregulated expression of a Krüppel zinc finger gene, BCL11A, in 4 cases of B-cell malignancy with t(2;14)(p13;q32.3).

Patients, materials, and methods

Patient material

Four patients with B-cell malignancies and t(2;14)(p13;q32) were studied. Patient material was studied after obtaining written informed consent and local ethical committee approval. Two unusual pediatric patients with CLL (referred to here as patients AS and LH) who exhibited this translocation have been reported on previously10; the translocation breakpoints in these 2 cases were cloned using bacteriophage cloning.11 In addition, 2 adult patients identified from our cytogenetic databases with identical translocations were also studied. Patient 3 was a previously well 62-year-old female who presented in July 1993 with generalized lymphadenopathy, 4-cm splenomegaly, and a white blood cell count (WBC) of 396 × 109/L, whose morphology and immunophenotype were consistent with CLL. She was treated with chlorambucil and subsequently with intravenous fludarabine but failed to respond to either and died with progressive disease in October 1995. Cytogenetics of this case showed 46,XX,t(2;14)(p13;q32)[14]/46,idem,t(3;6)(p21;q25),del(11)(q22q23)[2]/46,idem,add(8)(p23)[2] indicating that t(2;14)(p13;q32) was the primary cytogenetic abnormality. Patient 4 presented in February 1986 with generalized lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and a white blood cell count of 38.3 × 109/L with 84% lymphocytes. The clinical diagnosis of CLL was established. However, a lymph node biopsy was consistent with a lymphoplasmacytic immunocytoma according to the Kiel classification with increased proliferation activity and monoclonal IgM kappa expression. Cytogenetic analysis of both the lymph node specimen and of the peripheral blood showed the karyotype: 46,XY,t(2;14)(p13;q32),t(18;21)(p11;q21). In February 1992, the patient presented with clinical progression including lymphadenopathy, B-symptoms, and a WBC of 76.5 × 109/L with 85% lymphocytes. Histopathology of a repeat lymph node biopsy again revealed lymphoplacmacytic immunocytoma with increased proliferation activity. Chromosome analyses showed the tumor cells to contain the karyotype: 46,XY,t(2;14)(p13;q32),t(18;21)(p11;q21)[6]/46,idem,t(13;15)(?q12∼13;?q21)[3]. The patient died in 1999 due to progressive disease.

B-NHL and HD cell lines

The Wien 133 B-NHL cell line used in this study has been described.12 The NAB-2 Burkitt lymphoma cell line13 was kindly provided by Dr N Popescu, (National Institutes on Health [NIH], Bethesda, MD). The Raji B-NHL and the HD cell lines as well as the HEK293 human fibroblast cell line were obtained from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ), Braunschweig, Germany (Drexler14 andhttp://www.dsmz.de) or from Dr Stefan Joos, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg, Germany.

Long-distance inverse polymerase chain reaction

Long-distance inverse polymerase chain reaction (LDI-PCR) for rearrangements involving the IGHJ segments was performed as previously described.15 To amplify translocations involving the IGHS regions, primers were designed to amplify rearrangements of 5′ switch μ (Sμ). DNA was digested to completion with HindIII and ligated at low concentration followed by nested PCR using the following primers: SAE 5′-ACATAAATGAGTCTCCTGCTCTTCATCAAG-3′, SAI 5′-GCAATTAAGACCAGTTCCCCTTCTAGTG-3′, SME 5′-GGACTCAGATGGGCAAAAC-TGACCTAA-3′, SMI 5′-CTAGACTAAACAAGGCTGAACT-3′. These primers should detect the reciprocal translocation toIGHS translocations in which both derivative chromosomes are retained, so long as the translocation event occurred after regular class-switching (Figure 1A) (T.S., T.G.W., R.S., M.J.S.D., et al, unpublished data, December 2000). LDI-PCR products were cloned into and sequenced as previously described.3 16

Cloning of t(2;14)(p13;q32.3) breakpoint by 5′ Sμ LDI-PCR.

(A) Ideogram showing strategy used for LDI-PCR cloning of 5′ Sμ breakpoints. Top panel represents normal chromosome 14 with class-switched IGH VDJ fragment; middle panel, der(2)t(2;14)(p13;q32.3); and lower panel, der(14)t(2;14)(p13;q32.3). Class-switching results in 5′ Sμ sequences being retained whereas 3′ Sμ sequences are deleted. Most IGHS translocation breakpoints occur within switch regions that have already undergone class-switching, leaving the 5′ Sμ intact on the other derivative chromosome. These sequences can then be used to amplify the translocated allele using 5′ Sμ primers. Black horizontal lines represent chromosome 14; red lines, chromosome 2. The vertical red arrow represents the translocation breakpoint. Vertical lines representHindIII sites. (B) The left panel shows 1.6 kb LDI-PCR product obtained with 5′ Sμ primers; lane M denotes molecular weight markers. The right panel shows southern blot of DNA from patient 4 and DNA from a healthy individual (lane C) digested withHindIII and probed with a 5′ Sμ probe.34 An arrow points to a 2.1 kb rearranged band in patient 4. This was shown to be an illegitimate IGHS recombination event by reprobing with a 3′ Sμ probe (data not shown). Given the location of the DNA primers within 5′ Sμ this is the size of the LDI-PCR product anticipated from the southern blot results. (C) Location of translocation breakpoints within 2p13. Breakpoints derived from either bacteriophage cloning or LDI-PCR are shown in red. All 3 cloned breakpoints fell within 125 bp of each other.

Cloning of t(2;14)(p13;q32.3) breakpoint by 5′ Sμ LDI-PCR.

(A) Ideogram showing strategy used for LDI-PCR cloning of 5′ Sμ breakpoints. Top panel represents normal chromosome 14 with class-switched IGH VDJ fragment; middle panel, der(2)t(2;14)(p13;q32.3); and lower panel, der(14)t(2;14)(p13;q32.3). Class-switching results in 5′ Sμ sequences being retained whereas 3′ Sμ sequences are deleted. Most IGHS translocation breakpoints occur within switch regions that have already undergone class-switching, leaving the 5′ Sμ intact on the other derivative chromosome. These sequences can then be used to amplify the translocated allele using 5′ Sμ primers. Black horizontal lines represent chromosome 14; red lines, chromosome 2. The vertical red arrow represents the translocation breakpoint. Vertical lines representHindIII sites. (B) The left panel shows 1.6 kb LDI-PCR product obtained with 5′ Sμ primers; lane M denotes molecular weight markers. The right panel shows southern blot of DNA from patient 4 and DNA from a healthy individual (lane C) digested withHindIII and probed with a 5′ Sμ probe.34 An arrow points to a 2.1 kb rearranged band in patient 4. This was shown to be an illegitimate IGHS recombination event by reprobing with a 3′ Sμ probe (data not shown). Given the location of the DNA primers within 5′ Sμ this is the size of the LDI-PCR product anticipated from the southern blot results. (C) Location of translocation breakpoints within 2p13. Breakpoints derived from either bacteriophage cloning or LDI-PCR are shown in red. All 3 cloned breakpoints fell within 125 bp of each other.

Radiation hybrid mapping

Radiation hybrid (RH) mapping was performed with DNA primers 669 (5′-AATGGAGAGAGAGCGACAGG-3′) and 670 (5′-CTGCAGAAAGGCGAGAGG-3′) as well as 673 (5 TCCCAGTACAGCCCACATC -3′) and 674 (5′-GCAGGCGGCTGTTTATTC -3′) derived from the breakpoint sequence of the cloned LDI-PCR fragment by means of the Stanford G3 Panel (Research Genetics, Huntsville, AL). Map localization was calculated on the Stanford Human Genome Center RH server (http://www.shgc.stanford.edu).

Southern and Northern blotting

Southern and Northern blotting were carried out as described previously.3,16,17 EH3.0P was a 940-bp fragment from clone EH3.0.11,16 3′Sγ was a PCR product as previously described.18 The cDNA probe for BCL11A was clone 35.1XE, a 1.6-kb cDNA fragment containing the 5′ end ofBCL11A. RNA samples from normal adult and fetal human tissues were obtained from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA).

Fluorescence in-situ hybridization

Bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) and cosmid DNA and Alu-PCR products from yeast artificial chromosome (YAC) clones were labeled with biotin or digoxigenin using a random prime labeling kit (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) and fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) was carried out as previously described.19

In-situ hybridization studies

The 5′ 341 bp of BCL11A common to all 3 RNA isoforms was cloned into pCRII (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA), then amplified from this vector by PCR using M13 forward and reverse primers. A probe was generated from the PCR product by incubation for 1 hour in a 20-mL reaction containing 1 μg template DNA, 0.5 mM CTP, 0.5 mM GTP, 0.5 mM ATP, 0.005 mM UTP, 63 mCi (2331 MBq)35S-UTP, 2 U of either SP6 (sense) or T7 polymerase (antisense), and a 1X transcription buffer (Maxiscript; Ambion, Austin, TX). DNA was removed by addition of 2 U DNAse I for 15 minutes, and unincorporated nucleotides were removed by spin column. Tonsils were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde-phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) overnight at 4°C. Tissue was placed in 70% ethanol, dehydrated through graded ethanol solutions, cleared with xylene and infused with paraffin. Contiguous sections were probed with sense and antisense transcripts or stained, as described previously.20

Results

Molecular cloning of t(2;14)(p13;q32.3) translocation breakpoints

Four cases with t(2;14)(p13;q32.3) were studied; 3 cases exhibited t(2;14)(p13;q32.3) as the sole or primary cytogenetic abnormality. Cloning of 2 cases of pediatric CLL was performed using conventional bacteriophage cloning and has been reported previously.11In both cases the IGH breaks fell within theIGSγ2 region. The third case, of leukemic transformation of immunocytoma (patient 4), which exhibited t(18;22)(p11;q21) in addition to t(2;14)(p13;q32.3), was studied using LDI-PCR methods.15 Two rearranged IGHJ alleles were observed on Southern blotting (data not shown); both were amplified, cloned, and sequenced. Neither contained the translocation breakpoint (T.S. et al, unpublished data, December 1999).

These data therefore raised the possibility that the IGHbreak might fall within the switch (IGHS) regions. There are 9 IGHS regions. To clone all possible IGHStranslocations using LDI-PCR would require a large number of primer pairs. In an attempt to simplify the process we devised an LDI-PCR method designed to amplify the other derivative chromosome. Briefly, in cases of IGHS translocations where both derivative chromosomes are retained, so long as the translocation occurred after regular IG class-switching, it should be possible to LDI-PCR amplify from the translocated 5′Sμ sequence onto the other derivative chromosome, since the 5′Sμ sequence should remain intact. The strategy for cloning such translocations from 5′Sμ is depicted schematically in Figure 1A.

PCR primers were designed to this region and in an attempt to amplify the der(2)t(2;14)(p13;q32.3) from patient 4. High-molecular-weight DNA was digested with HindIII and ligated overnight to promote circularization of DNA fragments after restriction endonuclease inactivation. Using 5′Sμ primers, a product of 1.6 kb was obtained, cloned, and sequenced (Figure 1B). Sequence analysis showed loss of homology with IG sequences beyond Sμ and identity to a partially sequenced BAC clone RP11-440P05. Comparison of the derived sequence showed that this break fell in close proximity to those previously described for the 2 cases of pediatric CLL (Figure 1C). To confirm that no artifacts had been introduced during the LDI-PCR, cloning, and sequencing, Southern blot with probes spanning theIGH locus and a single-copy probe from the translocation breakpoint showed comigration of rearranged IGH and 2p13 fragments (data not shown).

To confirm that the novel sequence was genuinely derived from chromosome 2p13, RH mapping was performed. According to RH mapping, the breakpoint sequence was closely linked (0 cRs; LOD 6.88) to marker SHGC-21466 (AFMa126yd1, D2S2160). This marker is located 84.0 cM from top of chromosome 2 according to the genetic map (http://carbon.wi.mit.edu:8000/), which refers approximately to 2p12 to 16 in the cytogenetic map (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genemap99). In addition, BAC clones containing the breakpoint were mapped to chromosome 2p13 on metaphase spreads from healthy individuals and from patients with t(2;14)(p13;q32) by FISH. Results for a single BAC clone are shown in Figure 2A. In metaphase and interphase preparations from patient 4, BAC clones were shown to span the translocation breakpoint (Figure 2B). In patient 3, an adult with rapidly progressive and chemotherapy-resistant CLL in which t(2;14)(p13;q32.3) was the primary cytogenetic abnormality, it was not possible to amplify the translocation breakpoint using the same LDI-PCR method. However, this case also showed split of the FISH probe for theBCL11A locus as well as rearrangement and comigration of the 2p13 probe on Southern blot, indicating that the 2p13 breakpoint also fell within the same cluster region (Figure 2C,D).

FISH analysis demonstrating recurrent involvement of

BCL11A in cases with t(2;14)(p13;q32.3). (A) mBAC RP11-440P05 (AC009970) (red signal) hybridized to metaphases derived from a healthy individual maps to chromosome region 2p13. A centromeric probe for chromosome 2 (green) is also shown. (B) FISH with RP11-440P05 (red) on a t(2;14)(p13;q32.3) positive metaphase from patient 4. Apart from the intact chromosome 2, signals for the BAC were detected on both derivative chromosomes, indicating that it spanned the breakpoint. Inset: FISH with cosIgCα1 (green) hybridizing to theIGH-locus and RP11-440P05 (red signal) on interphase cells from patient 4. The cell lacking the translocation contains 2 isolated red and green signals. The fusion signal in the other cell represents the der(14) t(2;14)(p13;q32.3). The minor signal remaining on the der(2) chromosome could not be detected reliably in interphase cells. (C) FISH with pooled BCL11A-specific clones RP11-440P05 and RP11-158I21 (green AC007831) and 2 pooledREL-specific YAC clones 747H5 and 927G9 (red) on interphase nuclei of patient 3 with t(2;14)(p13;q32.3). On an intact chromosome 2 the REL- and BCL11A-specific signals colocalized. Translocation led to the disruption of the greenBCL11A-specific signal with a minor part remaining colocalized with the REL-signal on the der(2) and the major part on the der(14) separated from the REL-specific signal. (D) Southern blot analysis of t(2;14)(p13;q32.3) from patient 3. DNA from patient 3 digested with HindIII and probed withIG 3′Sγ probe and derived 2p13 breakpoint probe, EH3.0P31 showing comigration of one rearranged Sγ and 5′BCL11A sequences in this case. Left lane denotes control DNA; right lane, DNA from patient 3.

FISH analysis demonstrating recurrent involvement of

BCL11A in cases with t(2;14)(p13;q32.3). (A) mBAC RP11-440P05 (AC009970) (red signal) hybridized to metaphases derived from a healthy individual maps to chromosome region 2p13. A centromeric probe for chromosome 2 (green) is also shown. (B) FISH with RP11-440P05 (red) on a t(2;14)(p13;q32.3) positive metaphase from patient 4. Apart from the intact chromosome 2, signals for the BAC were detected on both derivative chromosomes, indicating that it spanned the breakpoint. Inset: FISH with cosIgCα1 (green) hybridizing to theIGH-locus and RP11-440P05 (red signal) on interphase cells from patient 4. The cell lacking the translocation contains 2 isolated red and green signals. The fusion signal in the other cell represents the der(14) t(2;14)(p13;q32.3). The minor signal remaining on the der(2) chromosome could not be detected reliably in interphase cells. (C) FISH with pooled BCL11A-specific clones RP11-440P05 and RP11-158I21 (green AC007831) and 2 pooledREL-specific YAC clones 747H5 and 927G9 (red) on interphase nuclei of patient 3 with t(2;14)(p13;q32.3). On an intact chromosome 2 the REL- and BCL11A-specific signals colocalized. Translocation led to the disruption of the greenBCL11A-specific signal with a minor part remaining colocalized with the REL-signal on the der(2) and the major part on the der(14) separated from the REL-specific signal. (D) Southern blot analysis of t(2;14)(p13;q32.3) from patient 3. DNA from patient 3 digested with HindIII and probed withIG 3′Sγ probe and derived 2p13 breakpoint probe, EH3.0P31 showing comigration of one rearranged Sγ and 5′BCL11A sequences in this case. Left lane denotes control DNA; right lane, DNA from patient 3.

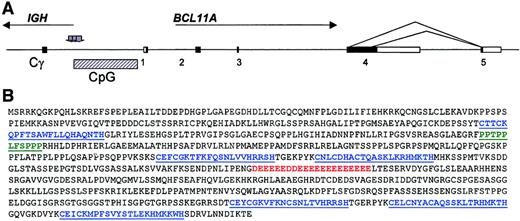

Identification of BCL11A

Comparison of the breakpoint sequences from the 3 cloned cases showed that all were clustered immediately centromeric to a CpG island associated with the 5′ end of a gene. Due to the direct involvement of this gene in 4 cases of B-cell malignancy with t(2;14)(p13;q32.3), we termed this gene BCL11A (B-cell lymphoma/leukemia 11A). An ideogram of the structure of the translocation and theBCL11A transcripts is shown in Figure3A. In B-NHL, IG chromosomal translocation breakpoints frequently fall in the vicinity of CpG islands.1 CpG islands are associated with genes, which are often expressed in a tissue-specific fashion.21 To identify the associated gene, a combination of extensive cDNA library screening using derived genomic probes was used17; probing a fetal brain cDNA library with genomic probes adjacent to the CpG island allowed the identification of the 5′ end of the gene. Additionally, genomic and EST DNA database searching (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/dbEST/), Northern blotting, and 3′ reverse transcriptase (RT)–PCR methods were used to define the full-length transcripts. A longest transcript of 5941 bp was identified, containing an open-reading frame of 835 amino acids, with a predicted molecular weight of 91.3 kd. The predicted amino acid sequence is shown in Figure 3B.

Ideogram of the genomic organization of the

BCL11A gene, the structure of the t(2;14)(p13;q32.3) translocation, and the predicted primary amino acid sequence ofBCL11A. (A) Ideogram of t(2;14)(p13;q32.3). All 4IGH breaks occurred within Sγ regions, whereas the 2p13 breaks clustered centromeric of a CpG island. Sequence comparison of genomic and expressed sequences from chromosome 2p13 showed the presence of 5 exons with the alternative splices indicated. Shaded arrows denote sites of breakpoints in cloned cases. Comparison of the derived cDNA sequences with the genomic sequence NT_005399.3 showed the presence of 3 common exons to all common BCL11A RNA isoforms: exon 1 represented nucleotides 370479-370761; exon 2, 377671-378005; and exon 3, 455146-455254. The longest isoform comprised exons 1-4 (exon 4, nucleotides 461558-466783), whereas the 2 common shorter isoforms exhibited alternative splicing from within exon 4 to an additional exon (exon 5, 471315-472815). (B) Predicted amino acid sequence of the longest detected BCL11A RNA isoform showing the presence of 6 C2H2 motifs (shown in blue), a sequence of 21 consecutive acidic amino acids shown in red, and a proline-rich region between the first and second zinc fingers, shown in green (accession no. AJ404611).

Ideogram of the genomic organization of the

BCL11A gene, the structure of the t(2;14)(p13;q32.3) translocation, and the predicted primary amino acid sequence ofBCL11A. (A) Ideogram of t(2;14)(p13;q32.3). All 4IGH breaks occurred within Sγ regions, whereas the 2p13 breaks clustered centromeric of a CpG island. Sequence comparison of genomic and expressed sequences from chromosome 2p13 showed the presence of 5 exons with the alternative splices indicated. Shaded arrows denote sites of breakpoints in cloned cases. Comparison of the derived cDNA sequences with the genomic sequence NT_005399.3 showed the presence of 3 common exons to all common BCL11A RNA isoforms: exon 1 represented nucleotides 370479-370761; exon 2, 377671-378005; and exon 3, 455146-455254. The longest isoform comprised exons 1-4 (exon 4, nucleotides 461558-466783), whereas the 2 common shorter isoforms exhibited alternative splicing from within exon 4 to an additional exon (exon 5, 471315-472815). (B) Predicted amino acid sequence of the longest detected BCL11A RNA isoform showing the presence of 6 C2H2 motifs (shown in blue), a sequence of 21 consecutive acidic amino acids shown in red, and a proline-rich region between the first and second zinc fingers, shown in green (accession no. AJ404611).

Most of the BCL11A gene sequence was contained within BAC RP11-158I21. Comparison of the cDNA and genomic sequences showed the presence of 5 exons. The structure of the translocation was a “head-to-head” arrangement, with the breakpoints falling centromeric to the first exon (Figure 3A). In the 2 cases with t(2;14)(p13;q32.3) of pediatric CLL in which there was adequate material, Northern blotting showed overexpression of this gene in comparison with other normal and malignant lymphoid tissues (Figure4B and data not shown). Neither of these 2 cases showed REL overexpression on Northern blot.11 Given the clear overexpression ofBCL11A in cases with t(2;14)(p13;q32) and the close physical association of the gene to the translocation breakpoints, we now consider the 2.85-kb transcript originally reported to be involved in this translocation to have been artifactual11; this transcript does not appear to represent any recognized RNA isoform ofBCL11A.

BCL11A RNA expression in fetal, adult, and malignant tissues.

(A) Low-level expression of BCL11A RNA in a range of normal adult lymphoid tissues and fetal liver (Clontech Immune System MTN blot; 2 μg poly[A+] mRNA per lane; exposure time, 10 days). A low-level BCL11A transcript of 5.8 kb was seen, with highest levels present in normal lymph node. (B) High-level BCL11Aexpression was seen only in fetal brain (CNS d117) and in patient AS with t(2;14)(p13;q32.3). Predominant BCL11A transcripts of 5.8 kb, 3.5 kb, and 1.5 kb were seen in cases with t(2;14)(p13;q32.3) and in fetal brain. Otherwise, note low-level expression ofBCL11A in malignant B-cell lines (NAB-2 and Granta 452) and in human embryonic kidney fibroblast cell line, HEK-293. Loading control denoted by reprobing of same filters with glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) probe shown below. (C) BCL11A mRNA accumulates in germinal center (GC) but not follicular mantle (FM) B cells. Antisense (i) and sense (ii)35S-labeled riboprobes were hybridized to frozen sections of normal human tonsils, or a serial section (iii) was weakly stained with Giemsa to visualize the boundary of the high cellularity FM area. GC cells but not mantle cells exhibited BCL11Aexpression.

BCL11A RNA expression in fetal, adult, and malignant tissues.

(A) Low-level expression of BCL11A RNA in a range of normal adult lymphoid tissues and fetal liver (Clontech Immune System MTN blot; 2 μg poly[A+] mRNA per lane; exposure time, 10 days). A low-level BCL11A transcript of 5.8 kb was seen, with highest levels present in normal lymph node. (B) High-level BCL11Aexpression was seen only in fetal brain (CNS d117) and in patient AS with t(2;14)(p13;q32.3). Predominant BCL11A transcripts of 5.8 kb, 3.5 kb, and 1.5 kb were seen in cases with t(2;14)(p13;q32.3) and in fetal brain. Otherwise, note low-level expression ofBCL11A in malignant B-cell lines (NAB-2 and Granta 452) and in human embryonic kidney fibroblast cell line, HEK-293. Loading control denoted by reprobing of same filters with glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) probe shown below. (C) BCL11A mRNA accumulates in germinal center (GC) but not follicular mantle (FM) B cells. Antisense (i) and sense (ii)35S-labeled riboprobes were hybridized to frozen sections of normal human tonsils, or a serial section (iii) was weakly stained with Giemsa to visualize the boundary of the high cellularity FM area. GC cells but not mantle cells exhibited BCL11Aexpression.

BCL11A RNA and protein isoforms

To determine the patterns of expression of BCL11A, Northern blotting, in-situ hybridization, and database searching were performed. Northern blotting showed low-level or undetectableBCL11A RNA expression in most adult tissues. Among adult tissues, highest levels of expression were seen in normal lymph node, thymus, and bone marrow, although levels of expression were low (Figure4A); the predominant, if not exclusive BCL11A RNA isoform was the 5.8-kb transcript. Some developmental stages of fetal brain showed levels comparable to those seen in leukemias with t(2;14)(p13;q32.3),17 (also Figure 4B and data not shown).BCL11A is represented by the Unigene cluster Hs.130881 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/UniGene/index.html). Among the 114 EST clones represented by this cluster, 32% were derived from germinal center B-cell or CLL cDNA libraries, 16% from fetal brain, and 16% from fetal and adult lung. EST clones corresponding to the 3′UTR of the gene were included on the “lymphochip”22; analysis of these data showed that BCL11A RNA is expressed in germinal center B cells and is down-regulated in response to anti-Ig stimulation (http://lmpp.nih.gov/lymphoma). To confirm expression of BCL11A within the germinal center, in-situ hybridization using antisense RNA probes was performed (Figure 4C). Staining with the antisense probe was seen only within the germinal center and not in the adjacent mantle zone, indicating tightly regulated expression of BCL11A during B-cell development.

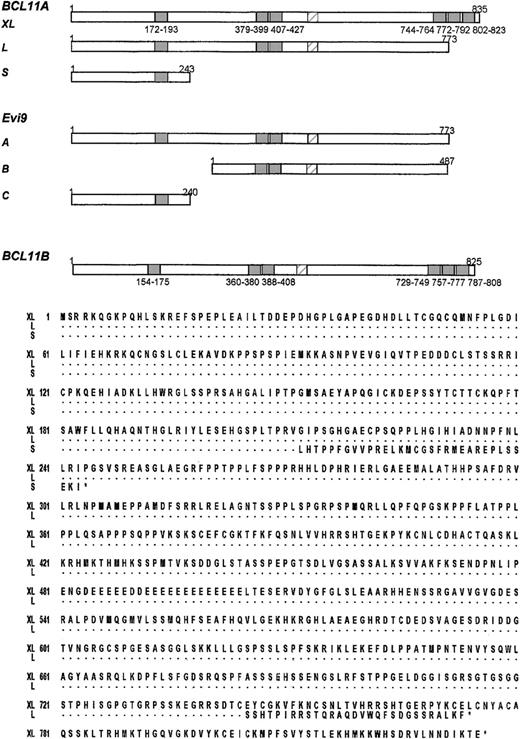

In both normal fetal brain and malignant B cells with t(2;14)(p13;q32.3), 3 major BCL11A transcripts of 5.8 kb, 3.8 kb, and 1.5 kb were observed. In the 2 pediatric CLL cases with t(2;14)(p13;q32) that were studied, there was overexpression of all 3 isoforms (Figure 4B). Heterogeneity within the 2 lower bands was observed on Northern blot. The full-length sequences of the 3 most common transcripts were determined from cDNA and EST clones. Comparison of the genomic and the derived cDNA sequences showed that the 3 commonBCL11A RNA isoforms derived from the 5 exons (Figure 3A). All 3 isoforms contained the first 3 exons. The longest isoform contained sequences from exons 1 to 4 only. Alternative splicing within exon 4 to a fifth exon resulted in 2 other common transcripts (Figure3A). Other splice variants were detected by RT-PCR analysis, but were less frequent (data not shown). We termed the 5.8 kb, 3.8 kb, and 1.5 kb RNA isoforms BCL11AXL,BCL11AL, andBCL11AS, respectively. The overall structure and the predicted amino acid sequences of the splice variants BCL11AL andBCL11AS, representing the 3.8-kb and 1.5-kb transcripts are shown in Figure 5A-B. Normal B-cell populations expressed the 5.8-kb BCL11AXL isoform preferentially, whereas the BCL11AS isoform was expressed preferentially in derived B-cell malignant cell lines (Figure4A,B and Figure 7). The possible significance of this observation is not clear.

BCL11AXL contained 6 Krüppel C2H2 zinc fingers as well as a proline-rich domain between zinc fingers 1 and 2 and an acidic domain between 3 and 4 containing a run of 21 consecutive acidic residues. The zinc fingers showed homology to each other. Zinc fingers 1 and 6 were different from 2, 3, 4, and 5 in that they had 4 amino acids separating the 2 zinc-binding histidines, whereas 2, 3, 4, and 5 had 3 amino acids. The internal zinc fingers (2, 3, 4, and 5) were arranged in pairs, each pair being separated by a canonical “linker” sequence; these pairs were nearly duplicated, with 37 of 49 amino acids being identical. The alternative isoforms showed alterations in the carboxy-terminus and thus in the terminal zinc fingers (Figure5A,B).

Sequence comparisons of

BCL11A, Evi9, and BCL11B. (A) Comparison ofBCL11A, previously isolated mouse Evi9 isoforms, and BCL11B. C2H2 zinc fingers are denoted by shaded boxes, the acidic region is denoted by a hatched box. The positions of the first and last amino acids of C2H2 zinc fingers are shown underneath. Note lack of last 3 zinc fingers in the longest mouse Evi9isoform and close similarities in the overall structure ofBCL11AXL and BCL11B. (B)BCL11A isoforms. Proteins of 835 (BCL11AXL, accession no. AJ404611), 773 (BCL11AX, accession no. AJ404612), and 243 (accession no. AJ404613) amino acids resulting from the common alternative splices. Dots represent identical amino acid residues.

Sequence comparisons of

BCL11A, Evi9, and BCL11B. (A) Comparison ofBCL11A, previously isolated mouse Evi9 isoforms, and BCL11B. C2H2 zinc fingers are denoted by shaded boxes, the acidic region is denoted by a hatched box. The positions of the first and last amino acids of C2H2 zinc fingers are shown underneath. Note lack of last 3 zinc fingers in the longest mouse Evi9isoform and close similarities in the overall structure ofBCL11AXL and BCL11B. (B)BCL11A isoforms. Proteins of 835 (BCL11AXL, accession no. AJ404611), 773 (BCL11AX, accession no. AJ404612), and 243 (accession no. AJ404613) amino acids resulting from the common alternative splices. Dots represent identical amino acid residues.

Conservation of BCL11A and identification of a homologue (BCL11B) on chromosome 14q32.1

BCL11A showed a high level of conservation across a wide range of species. BCL11A is the human homologue of mouse Evi9, being 94% identical at nucleotide levels, and 98% identical at protein levels. Evi9 was isolated in a search for murine leukemia genes using proviral integration.23,24 The same mouse gene has been isolated as an interacting partner (CTIP-1) of the orphan nuclear receptor COUP-TF2.24 Like BCL11A, 3 common isoformsEvi9/CTIP-1 were identified.23 However, the mouse and human isoforms did not correspond exactly. The intermediate splice form reported for Evi9 has not been seen in humans (Figure 5A). Rat, chicken, Xenopus, and zebrafishBCL11A homologues have also been identified (data not shown).

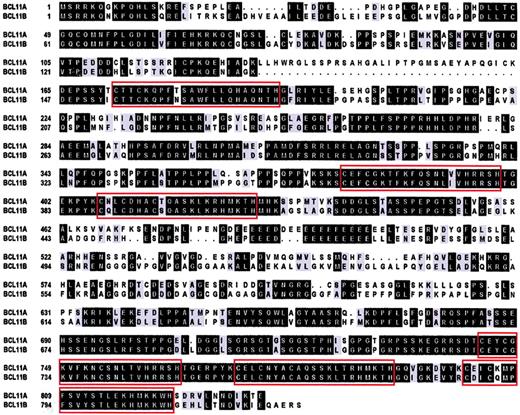

Apart from being evolutionarily conserved, database analysis showed a human homologue of BCL11A mapping to chromosome 14q32.1. This gene (BCL11B) was 67% identical to BCL11Aat the nucleotide level and 61% identical overall at the protein level. BCL11B, like BCL11A, contained 6 C2H2 zinc fingers and proline-rich and acidic regions with 95% identity in the zinc finger domains (Figure6). Like BCL11A,BCL11B was remarkable in having a large 5′ CpG island.BCL11B is the homologue of mouse CTIP-2 and is 86% identical at the protein level.25BCL11B was expressed preferentially in malignant T-cell lines derived from patients with adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma; the possible pathologic significance of this observation is not clear. BCL11B was not expressed at detectable levels by Northern blot in any malignant B-cell lines examined (data not shown).

Sequence comparison of

BCL11AXL andBCL11B. Boxed regions indicate C2H2 zinc finger domains. Identical amino acids are shown in black boxes, conserved in gray. Introduced gaps to maximize the alignment are shown as dots. BCL11B accession no. AJ404614.

Sequence comparison of

BCL11AXL andBCL11B. Boxed regions indicate C2H2 zinc finger domains. Identical amino acids are shown in black boxes, conserved in gray. Introduced gaps to maximize the alignment are shown as dots. BCL11B accession no. AJ404614.

Involvement of BCL11A in B-NHL and HD cell lines with abnormalities of chromosome 2p13

Both BCL11A and BCL11B map to regions of recurrent cytogenetic abnormality in lymphoid malignancies. Amplifications and gains of 2p13 have been commonly detected, not only in various subtypes of B-NHL, including 20% of aggressive extra-nodal and mediastinal B-NHL but also in 50% of primary cases of HD.26-31REL was amplified in all these B-NHL subtypes, although the pathologic consequences remain to be determined. In the BAC contig of the region, BCL11A mapped closely telomeric (about 300kb) of REL (HFPCctg13617;http://genome.wustl.edu, NCBI homo sapiens chromosome 2 working draft sequence segment NT_005399), and was shown to be coamplified withREL by FISH in primary material from a panel of patients with B-NHL (Figure 7A and data not shown). Unfortunately, there was no suitable material available from any of these cases for RNA analysis. Gains of chromosome 2p13 have recently been described in up to 50% of primary cases of HD.30 In line with these observations, supernumerary copies of the BCL11A locus, including high-level amplifications, were detected in primary HD disease cases (Martin-Subero et al, unpublished data, May 2001). Moreover, of 6 HD cell lines examined, L428 and KM-H2 exhibited overexpression ofBCL11A by Northern blot (Figure 7B). All 3 isoforms were expressed co-ordinately in KM-H2, whereas L428 showed high-level expression of only BCL11AL. In contrast, the 4 other HD and other B-NHL cell lines exhibited low-level expression of all 3 BCL11A isoforms (Figure 7B and data not shown).

BCL11A amplification and overexpression in Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

(A) BCL11A amplification in a primary case of B-NHL. FISH with 2 pooled BCL11A-specific BACs RP11-440P05 and RP11-158I21 (green signal) and 2 pooled REL-specific YAC clones 747H5 and 927G9 (red signal) on interphase nuclei from a case of relapsed t(14;18)(q32.3;q21.3)–negative nodal follicular lymphoma showing coamplification of BCL11A and REL. Chromosome analysis revealed 2 abnormal chromosomes 2, add(2)(p14∼15) and der(1)t(1;2)(p11;p11)trp(2)(p12p13). (B) Northern blot analysis of malignant lymphoma cell lines. Burkitt lymphoma cell lines Wien 133 and Raji, and HD cell line L540, showed low-level BCL11Aexpression. HD cell lines L428 and KM-H2 showed overexpression ofBCL11A. In L428, this was predominantly ofBCL11AL, whereas in KM-H2 all 3 isoforms were expressed at similar levels.

BCL11A amplification and overexpression in Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

(A) BCL11A amplification in a primary case of B-NHL. FISH with 2 pooled BCL11A-specific BACs RP11-440P05 and RP11-158I21 (green signal) and 2 pooled REL-specific YAC clones 747H5 and 927G9 (red signal) on interphase nuclei from a case of relapsed t(14;18)(q32.3;q21.3)–negative nodal follicular lymphoma showing coamplification of BCL11A and REL. Chromosome analysis revealed 2 abnormal chromosomes 2, add(2)(p14∼15) and der(1)t(1;2)(p11;p11)trp(2)(p12p13). (B) Northern blot analysis of malignant lymphoma cell lines. Burkitt lymphoma cell lines Wien 133 and Raji, and HD cell line L540, showed low-level BCL11Aexpression. HD cell lines L428 and KM-H2 showed overexpression ofBCL11A. In L428, this was predominantly ofBCL11AL, whereas in KM-H2 all 3 isoforms were expressed at similar levels.

Discussion

The molecular cloning of IG translocation breakpoints allows the identification of genes that play an important role in the genesis of normal and malignant B-cells. Chromosomal translocation t(2;14)(p13;q32.3) occurs as the sole cytogenetic abnormality in a rare but clinically aggressive subset of CLL/immunocytoma, suggesting that deregulated expression of BCL11A may play a major and primary role in the pathogenesis of this disease. Whether similar deregulated expression occurs by other mechanisms in other cases of CLL lacking the translocation is currently under investigation. However, the identification of BCL11A is of interest for several additional reasons. First, BCL11A is the homologue of the murine gene Evi9 that was isolated in a search for dominant transforming oncogenes using retroviral insertional mutagenesis. This gene was found to be deregulated in 2 of 205 myeloid leukemias induced in the BXH2 mouse strain following proviral integration within the first intron ofEvi9.23,24 These data strongly implicateEvi9 as a dominant oncogene. Some derived leukemias lackingEvi9 proviral integration nevertheless showed high-levelEvi9 expression (Figure 1C and Nakamura et al24) suggesting that other mechanisms may drive deregulated expression of Evi9. It was subsequently shown that 2 of the 3 Evi9 isoforms (Evi9a andEvi9c) but not the intermediate form Evi9b, were capable of inducing in vitro anchorage independence of murine NIH3T3 fibroblasts.24 While this manuscript was in preparation, the same group reported the isolation of some isoforms of the human homologue via homology with the mouse gene and showed that humanEVI9/BCL11A was expressed in CD34+ myeloid precursors and down-regulated in retinoic acid–induced differentiation of HL-60 cells.32 Second, some but not all isoforms of murine Evi9 were capable of interacting directly withBCL6.24 We have confirmed these observations with BCL11A and have shown additionally thatBCL11A is a DNA sequence–specific transcriptional repressor (H.L. et al, unpublished data). Finally, BCL11A is also of interest as it may be another target gene for amplifications and gains of chromosome 2p13 in B-cell malignancies and HD. The true frequency of these amplifications is not clear as they may occur in the absence of changes detectable by comparative genomic hybridization (CGH), but they have been detected in B-NHL of various histologic subtypes as well as HD. Taken with the data from the t(2;14)(p13;q32.3) translocation, the close linkage ofBCL11A with REL on chromosome 2p13 and the coamplification of the 2 genes, suggest that deregulated expression ofBCL11A may have a role in the pathogenesis of divergent subtypes of aggressive human B-NHL and HD. Studies on the relative expression of BCL11A and REL in primary cases of B-cell malignancy and HD are currently being undertaken, but it is difficult to demonstrate this point directly in many cases as RNA is often not available. Detection of BCL11A expression in HD may be of particular value, since there is currently a lack of genetic markers for this disease.33BCL6 expression in HD defines a distinct subset of disease.34 The possible diagnostic and prognostic significance of BCL11Aoverexpression in both HD and B-NHL, and the possible correlation withBCL6 expression, await the development of antibodies suitable for use in paraffin sections. Whether BCL11B is targeted in lymphoid malignancies such as adult T-cell leukemia, where translocations and amplifications of 14q32.1, which do not involve theTCL1 gene complex and which lie about 4 megabases (Mb) centromeric of BCL11B are common, is currently under investigation.35

We gratefully acknowledge Janet Koslovsky, Judith Gerbach, Charlotte Fleischer, Claudia Becher, and Dorit Schuster for providing technical assistance; Dr Stefan Joos, DKFZ, Heidelberg, and Dr Hans Drexler, DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany, for providing HD lines. We thank Dr Nicolae Popescu (NIH, Bethesda, MD) for kindly providing the Burkitt cell line NAB-2.

Supported by grants from the Bud Flanagan Leukaemia Fund, the Leukaemia Research Fund, the Kay Kendall Leukaemia Fund, the Lady Tata Memorial Foundation, The Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation, The Human Resources Support Foundation of Kumamoto City (“Hitozukuri Kikin”), Deutsche Krebshilfe and the IZKF Kiel, National Institutes of Health grant AI18016 and Welch Foundation grant F-1376.

E.S., T.S., and T.G.W. contributed equally to this report.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

P. W. Tucker, University of Texas at Austin, Institute for Cellular and Molecular Biology, Molecular Genetics and Microbiology, ESB 534, 100W 24th St, Austin, TX 78705; e-mail:philtucker@mail.utexas.edu, or Martin J. S. Dyer, Department of Haematology, University of Leicester, Robert Kilpatrick Clinical Sciences Bldg, Leicester Royal Infirmary, PO Box 65, Leicester, LE2 7LX, United Kingdom; e-mail: mjsd1@le.ac.uk.

![Fig. 4. BCL11A RNA expression in fetal, adult, and malignant tissues. / (A) Low-level expression of BCL11A RNA in a range of normal adult lymphoid tissues and fetal liver (Clontech Immune System MTN blot; 2 μg poly[A+] mRNA per lane; exposure time, 10 days). A low-level BCL11A transcript of 5.8 kb was seen, with highest levels present in normal lymph node. (B) High-level BCL11Aexpression was seen only in fetal brain (CNS d117) and in patient AS with t(2;14)(p13;q32.3). Predominant BCL11A transcripts of 5.8 kb, 3.5 kb, and 1.5 kb were seen in cases with t(2;14)(p13;q32.3) and in fetal brain. Otherwise, note low-level expression ofBCL11A in malignant B-cell lines (NAB-2 and Granta 452) and in human embryonic kidney fibroblast cell line, HEK-293. Loading control denoted by reprobing of same filters with glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) probe shown below. (C) BCL11A mRNA accumulates in germinal center (GC) but not follicular mantle (FM) B cells. Antisense (i) and sense (ii)35S-labeled riboprobes were hybridized to frozen sections of normal human tonsils, or a serial section (iii) was weakly stained with Giemsa to visualize the boundary of the high cellularity FM area. GC cells but not mantle cells exhibited BCL11Aexpression.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/98/12/10.1182_blood.v98.12.3413/6/m_h82311835004.jpeg?Expires=1767784075&Signature=oVAomCafHYZmDgCd0WFF1U3hQIiF~ALvZl-GEYEQxxEpaJIu4i94QNvYm6uRgou3t6OvyCO2~A5tOcw5VPKC~ewP2pU~YZOhQCa6ZNJkRl2-NnErO7ClOuQdkXWQnH5XVULgxn4CioJva9fREqBI7m6KHE5Oqa0lzBiycrk005bOppfh7k-KQ0TCMs8hoQTXAqEy8HEAc7o92lg5kdjI00Tgv1n3rarRE9sFzlPm8cIfyPK2TuWPR1w8Zipkz0NRsXD69m9FFcGBavt6tesR5xB6mYiqkEpV05GOScNWjlREtvR~P3QUzxpRTnE90xUNAPjtnylNJHMVzEVTvyteKQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 4. BCL11A RNA expression in fetal, adult, and malignant tissues. / (A) Low-level expression of BCL11A RNA in a range of normal adult lymphoid tissues and fetal liver (Clontech Immune System MTN blot; 2 μg poly[A+] mRNA per lane; exposure time, 10 days). A low-level BCL11A transcript of 5.8 kb was seen, with highest levels present in normal lymph node. (B) High-level BCL11Aexpression was seen only in fetal brain (CNS d117) and in patient AS with t(2;14)(p13;q32.3). Predominant BCL11A transcripts of 5.8 kb, 3.5 kb, and 1.5 kb were seen in cases with t(2;14)(p13;q32.3) and in fetal brain. Otherwise, note low-level expression ofBCL11A in malignant B-cell lines (NAB-2 and Granta 452) and in human embryonic kidney fibroblast cell line, HEK-293. Loading control denoted by reprobing of same filters with glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) probe shown below. (C) BCL11A mRNA accumulates in germinal center (GC) but not follicular mantle (FM) B cells. Antisense (i) and sense (ii)35S-labeled riboprobes were hybridized to frozen sections of normal human tonsils, or a serial section (iii) was weakly stained with Giemsa to visualize the boundary of the high cellularity FM area. GC cells but not mantle cells exhibited BCL11Aexpression.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/98/12/10.1182_blood.v98.12.3413/6/m_h82311835004.jpeg?Expires=1768246884&Signature=nIkgaqqo2mE10jBJJVKTkgcTAofuu6~NNNXFSYaX5Ck~5BIP6xWN3cWp~6PzAsp12zX-pmIna4qREyp2OxaBx4tigIu6-CJbrcwJOEF0uDL07cXGkUkCbAOYbgB0ozM6~m28aEC8EP2yLXLY8JS7exHx2-LVXEXY~ys3qU9rJ8tYGLX-TuscbxVeV2DKy69M-n567LjToIftkJ~kfrs2PHzpFZtuY5Obvqyg6yIZ4BE1FxEHGXYcXbSZtOgI4K2tVF7NJ54PJ2ZfDVVbkbB7UFg1RzD1R8efC1Zi9H10L6QCCS6TuX0i928kbE8u88BG~CR~~P~7ajhD46LDJVq5PA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)