Abstract

Erythropoietin (EPO) from sera obtained from anemic patients was successfully isolated using magnetic beads coated with a human EPO (hEPO)–specific antibody. Human serum EPO emerged as a broad band after sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, with an apparent molecular weight slightly smaller than that of recombinant hEPO (rhEPO). The bandwidth corresponded with microheterogeneity because of extensive glycosylation. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis revealing several different glycoforms confirmed the heterogeneity of circulating hEPO. The immobilized anti-hEPO antibody was capable of binding a representative selection of rhEPO glycoforms. This was shown by comparing normal-phase high-performance liquid chromatography profiles of oligosaccharides released from rhEPO with oligosaccharides released from rhEPO after isolation with hEPO-specific magnetic beads. Charge analysis demonstrated that human serum EPO contained only mono-, di-, and tri-acidic oligosaccharides and lacked the tetra-acidic structures present in the glycans from rhEPO. Determination of charge state after treatment of human serum EPO with Arthrobacter ureafaciens sialidase showed that the acidity of the oligosaccharide structures was caused by sialic acids. The sugar profiles of human serum EPO, describing both neutral and charged sugar, appeared significantly different from the profiles of rhEPO. The detection of glycan structural discrepancies between human serum EPO and rhEPO by sugar profiling may be significant for diagnosing pathologic conditions, maintaining pharmaceutical quality control, and establishing a direct method to detect the misuse of rhEPO in sports.

Introduction

Human erythropoietin (EPO) is a glycoprotein that is synthesized mainly in the kidney and that stimulates erythropoiesis through actions on erythroid progenitor cells.1-3 Human EPO (hEPO) was the first hematopoietic growth factor to be cloned.4,5 Recombinant hEPO (rhEPO) has been available as a drug since 1988 and is used in the clinical treatment of anemia, especially anemia caused by renal failure. In sports the misuse of rhEPO has been suspected among athletes for several years.6

Active hEPO consists of a single 165–amino acid polypeptide chain with three N-glycosylation sites at Asn24, Asn38, and Asn83, respectively, and one O-glycosylation site at Ser126. The average carbohydrate content is approximately 40%.7-9 Glycosylation is important for the biologic activity of EPO. Removal or modification of the glycan chains results in altered in vivo and in vitro activity.9-14 Furthermore, the number of sialic acid residues and the branching pattern of theN-linked oligosaccharides modify the pharmacodynamics, speed of catabolism, and biologic activity of hEPO.11,15 16

Oligosaccharide units, or glycans, of glycoproteins serve a variety of functions, including folding of nascent polypeptide chains in the endoplasmic reticulum, protection of the protein moieties from the action of proteases, and modulation of biologic activities.17-21 Synthesis of the polypeptide chain of a glycoprotein is genetically regulated in contrast to the oligosaccharide chains that are attached and processed by a series of enzyme reactions. Consequently, a glycoprotein generally appears as a mixture of glycoforms. These glycoform populations have been shown to be cell and species as well as polypeptide and site specific.22-25 Each glycoprotein, therefore, has a reproducible and characteristic glycosylation profile or glycosylation pattern.

Oligosaccharide structures of recombinant proteins also appear to be dependent on expression methods and culture conditions.26 27 Hamster cell lines such as Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) and baby hamster kidney (BHK) cells are common hosts for the production of recombinant human glycoproteins intended for therapeutic use. Three pharmaceuticals of rhEPO are available for clinical use. They are classified as epoetin alfa, epoetin beta, and epoetin omega according to the manufacturing method. Epoetin alfa and beta are both produced in CHO cells, whereas epoetin omega is produced in BHK cells.

Although CHO and BHK cells glycosylate proteins in a manner qualitatively similar to that in human cells, some human tissue–specific carbohydrate motifs are not synthesized by these cells because they lack the proper sugar-transferring enzymes. In contrast to human cells, CHO cells do not express sialyl-α 2-6 transferase, bisecting N-acetyl glucosamine transferase, and α 1-3/4 fucosyl transferase.14 28-31 In view of these differences, structural analysis of the sugar groups of natural and recombinant glycoproteins has become increasingly important.

The current study reports for the first time the isolation and sugar profiling of the oligosaccharide structures of human serum EPO and their comparison with rhEPO glycans. Important discrepancies between circulating hEPO and rhEPO based on protein structural data and glycan analyses are demonstrated.

Materials and methods

Iodination of recombinant human erythropoietin

Recombinant hEPO (epoetin alfa, a gift from Janssen-Cilag, Norway) was labeled with sodium iodide 125 (125I) to a specific activity of 40 μCi (1.5 MBq)/μg. EPO (2 μg) in 50 μL 0.05 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, and 0.2 mCi (7.4 MBq)125I were added to a tube containing 0.75 μg Iodogen (Pierce, Rockford, IL). After 5 minutes' incubation on ice, the mixture was loaded on a PD 10 gel filtration column (Sephadex G-25; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) to separate125I-rhEPO (tracer) from free iodine. Phosphate buffer with 0.2% human albumin was used as elution buffer.

Preparation of human erythropoietin–specific magnetic beads

Tosylactivated monodisperse magnetic polystyrene beads from Dynal AS (Oslo, Norway) were coated with a protein A affinity-purified rabbit antibody against CHO cell–derived rhEPO (R&D Systems, Oxford, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Maximal binding of 125I-rhEPO to the antibody-coated beads was obtained after 48 hours at ambient temperature, and these conditions were used in all subsequent experiments.32

Binding capacity of the hEPO-specific magnetic beads was calculated by Scatchard analysis of displacement studies.33 Magnetic beads (0.1 mg) were incubated with tracer (approximately 10 000 cpm) and rhEPO (5 U/L, 20 U/L, 200 U/L, 1000 U/L) in 0.25 mL potassium buffer (50 mM KH2PO4, 50 mM KOH, 0.1 M NaCl, and 8 mM azide [NaN3] with 0.1% [wt/vol] human serum albumin), pH 7.5. After incubation, the beads were washed and counted in a gamma counter. Dissociation constant (Kd) and number of binding sites were calculated from the Scatchard plots after correction for unspecific binding. Calculations were carried out using the KELL program from Biosoft (Cambridge, United Kingdom).

Erythropoietin assay

Serum levels of hEPO were determined by a solid-phase, 2-site sequential chemiluminescence enzyme immuno-metric assay (Immulite-EPO, DPC, Los Angeles, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunomagnetic extraction

To reduce unspecific binding, serum samples were treated with polyethylene glycol 6000 (12.5% wt/vol) to precipitate immunoglobulins34 and were centrifuged at 3500gfor 20 minutes before incubation with the antibody-coated magnetic beads. Human EPO–specific magnetic beads (130 mg) were incubated with 4 mL serum from anemic patients. Based on the calculated capacity of the beads, approximately 6.5 pmol EPO was extracted and subjected to further analyses. One mole hEPO with three N-linked glycosylation sites will give 3 moles oligosaccharides.

Subsequently, the beads were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) containing Tween-20 (1% vol/vol; BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), then with 0.5 M NaCl, and finally with 0.15 M NaCl. For protein analysis, human serum EPO was eluted from the beads by incubation with 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in PBS at ambient temperature under vigorous shaking for 30 minutes. SDS was removed by dialysis against PBS using Slide-A-Lyzer (Pierce) and subsequently human serum EPO was concentrated by ultrafiltration in Centricon YM-30 (Millipore, Bedford, MA). For oligosaccharide analyses, human serum EPO was eluted from the beads according to the method of Wognum et al.35 PBS with 0.1% polyethylene glycol 6000 made to a pH of 2.0 with HCl was mixed with the beads and vigorously shaken for 20 minutes at ambient temperature.

Biotinylation of monoclonal antihuman erythropoietin

A monoclonal anti-hEPO antibody36 (250 μg; clone AE7A5, protein G affinity-purified mouse IgG2A, developed against the 26 amino-terminal amino acids of rhEPO) (R&D Systems) was dissolved in 250 μL PBS and mixed with 30 μg Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Pierce). The mixture was incubated on ice for 2 hours. Free biotin was removed using 0.22-μm microfiltration units (Ultrafree-MC 5000 NMWL [nominal molecular weight limit]; Millipore).

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting

Subsequent to reducing SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE)37 in 12% gels (Mini Protean II; BioRad Laboratories), the proteins were blotted38 onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (0.2 μm; BioRad Laboratories), in a semidry blotting apparatus (Ancos, Hoejby, Denmark). After blotting, the membranes were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 5 hours and were incubated with the biotinylated monoclonal anti-hEPO antibody and streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Blots were visualized using a chemiluminescent substrate, LumiLight (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and CL-Xposure films (Pierce).

Two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

Isoelectric focusing (IEF) in immobilized pH gradient (IPG) strips (7 cm) (BioRad Laboratories) was performed with the sample included in the swelling solution as described by the manufacturer. The hEPO samples were focused at 200 V for 30 minutes and then at 2000 V for 5 hours. The current and the power settings were limited to 2 mA and 5 W, respectively. Subsequently, the strips were stored at −70°C. Before the second dimension was run in 12% polyacrylamide gels (SDS-PAGE), the IPG strips were equilibrated according to the manufacturer's instructions. SDS-PAGE was performed at 10 mA for 30 minutes until the bromphenol blue dye had completely migrated into the gel and then at 20 mA until the dye had reached the anodic end. After electrophoresis, the proteins were blotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and were immunostained as described above.

Enzymatic release of N-linked oligosaccharides

De-N-glycosylated EPO for protein analyses was obtained by treatment with recombinant N-glycosidase F (PNGase F) from Flavobacterium meningosepticum (New England BioLabs, Beverly, MA). For removal of all N-linked glycans, EPO was incubated for 24 hours at 37°C with PNGase F at a concentration of 0.08 U/μL in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, containing 10 mM EDTA and 0.02% azide. Partial digestion of EPO was obtained by using the same PNGase F at a concentration of 0.0008 U/μL at 37°C incubated at various time intervals, depending on the substrate.

Preparation of N-glycan pools for sugar analyses was performed by digesting the glycoprotein with PNGase F (glycerol-free) from Roche in conditions similar to those described above. Subsequent to enzymatic cleavage from the protein, N-glycans were purified using GlycoClean H solid-phase extraction cartridges from Glyko (Novato, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After cleaning, the glycan pools were filtered through Ultrafree-MC units (0.22 μm). Before labeling with fluorescence, the purified glycan samples were evaporated to complete dryness by vacuum centrifugation.

Fluorescence labeling of released oligosaccharides with 2-aminobenzamide

N-glycans were labeled in the reducing terminus by reductive amination using the 2-aminobenzamide (2-AB) signal labeling kit from Glyko. Excess label was removed using GlycoClean S cartridges from Glyko according to the manufacturer's instructions. The 2-AB–labeled glycan pools were subsequently vacuum dried, redissolved in water, and stored at −70°C.

Exoglycosidase enzyme digestion

Removal of terminal sialic acids from intact EPO and 2-AB–labeled glycans was performed with Arthrobacter ureafaciens sialidase (ABS; neuraminidase) from Glyko according to the methods of Guile et al39 and Rudd et al.40ABS removes terminal sialic acids linked via α 2-3, 2-6, and 2-8 to galactose,41 whereas branched sialic acids are not affected. 2-AB–labeled glycans were digested with ABS (5 U/μL) in 100 mM citrate–phosphate buffer, pH 5, containing 0.2 M zinc acetate (Zn(C2H3O2)2) and 0.15 M NaCl for 24 hours at 37°C. After treatment, the enzyme was removed by filtration in centrifugal filter units (Ultrafree-MC 5000 NMWL) from Millipore. Filters were washed with 15 μL 5% acetonitrile, which was added to the respective sample fractions. Resultant glycan samples were subsequently dried in a vacuum centrifuge and dissolved in water before further analysis.

Charge analysis of 2-aminobenzamide–labeled oligosaccharides

Separation of acidic and neutral 2-aminobenzamide–labeled oligosaccharides by normal-phase high-performance liquid chromatography

Separation of acidic and neutral hEPO glycans by normal-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was carried out using the GlycoSep N column from Glyko with the low-salt solvent system described by Guile et al.39 The column was calibrated using a 2-AB–labeled dextran hydrolysate (mixture of glucose oligomers).

Normal-phase HPLC is performed using a column with polar functional groups that interact with the hydroxyl groups on the oligosaccharides. The GlycoSep N column is capable of resolving both neutral and charged sugar residues on the basis of hydrophilic properties. In general, large glycans are more hydrophilic than small ones and require higher concentrations of aqueous solvent to be eluted.

Results

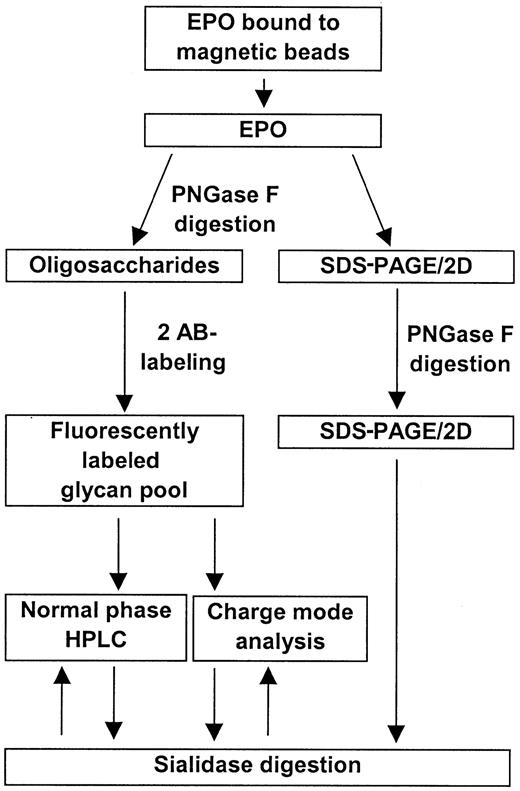

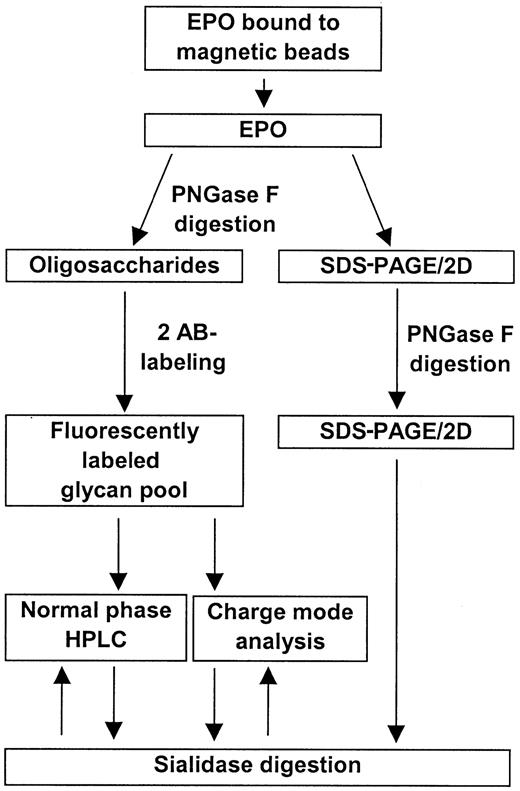

Isolation of human serum erythropoietin

EPO was successfully isolated from human serum samples using magnetic beads coated with an anti-hEPO antibody. Treatment of the serum samples with polyethylene glycol significantly improved the binding of EPO to the beads (data not shown). An overall scheme for the isolation and analysis of human serum EPO is shown in Figure1.

Overall scheme for the isolation and characterization of human serum EPO.

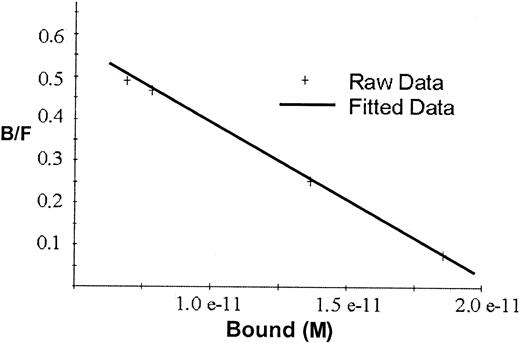

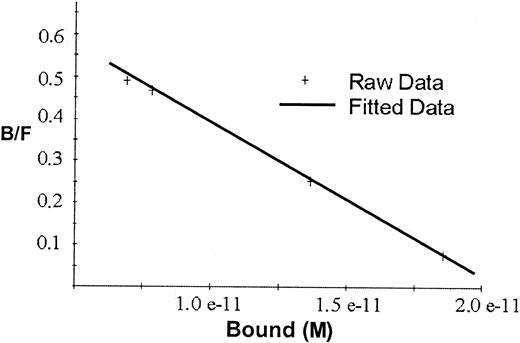

Scatchard analyses of the binding data for rhEPO in Figure2 gave a straight line indicating one single class of binding sites, with Kd2.7 × 10−11 mol/L and maximal binding capacity 2.1 × 10−11 mol/L, or approximately 50 fmol/mg beads.

Scatchard plot for the binding of 125I-rhEPO to hEPO-specific magnetic beads.

The line represents the correlation between bound and free125I-EPO ratio versus the tracer activity bound to the beads. Kd for rhEPO was 2.7 × 10−11 mol/L, and maximal binding capacity was 2.1 × 10−11 mol/L or approximately 50 fmol/mg beads.

Scatchard plot for the binding of 125I-rhEPO to hEPO-specific magnetic beads.

The line represents the correlation between bound and free125I-EPO ratio versus the tracer activity bound to the beads. Kd for rhEPO was 2.7 × 10−11 mol/L, and maximal binding capacity was 2.1 × 10−11 mol/L or approximately 50 fmol/mg beads.

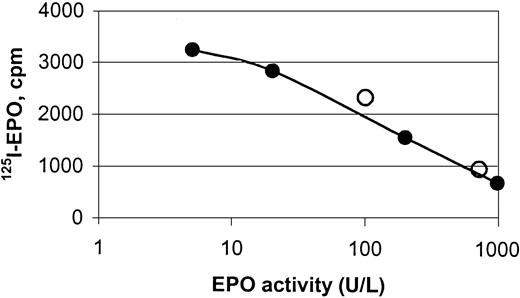

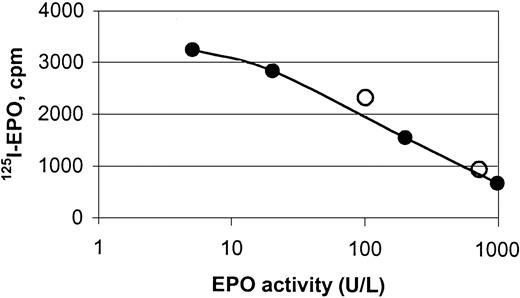

hEPO-specific beads were capable of binding endogenous hEPO from sera obtained from anemic patients, shown by binding studies and protein analyses (Figures 2, 3,4, and5). Specific binding of EPO from human sera to the magnetic beads was demonstrated by a competitive assay using 125I-rhEPO as indicator. Two samples of human sera with known concentrations of EPO and normal sera with 5 different concentrations of standard rhEPO were incubated with iodinated EPO. The ability of the beads to extract human serum EPO and rhEPO was clearly demonstrated (Figure 3).

Displacement curve for the binding of125I-rhEPO to hEPO-specific magnetic beads.

The curve depicts binding of human serum EPO (○) and rhEPO (●) to monodisperse magnetic beads coated with a polyclonal anti-rhEPO antibody, and it shows the displacement of 125I-rhEPO by increasing amounts of nonlabeled hEPO. Magnetic beads were incubated with hEPO (endogenous or recombinant) and rhEPO tracer for 48 hours under rotation at ambient temperature.

Displacement curve for the binding of125I-rhEPO to hEPO-specific magnetic beads.

The curve depicts binding of human serum EPO (○) and rhEPO (●) to monodisperse magnetic beads coated with a polyclonal anti-rhEPO antibody, and it shows the displacement of 125I-rhEPO by increasing amounts of nonlabeled hEPO. Magnetic beads were incubated with hEPO (endogenous or recombinant) and rhEPO tracer for 48 hours under rotation at ambient temperature.

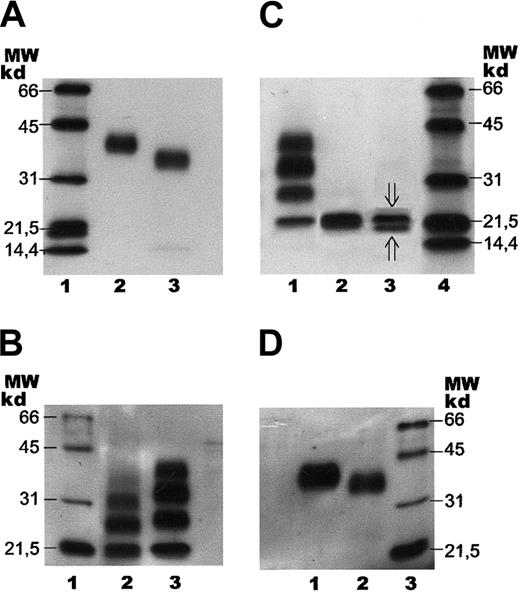

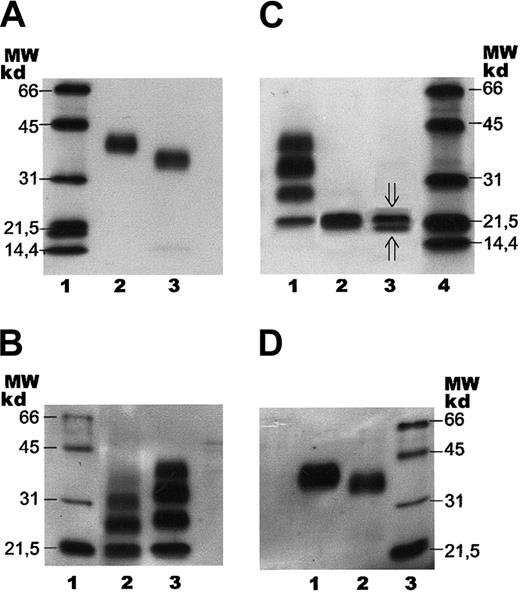

SDS-PAGE with subsequent immunoblotting of human serum EPO.

Separation of human serum EPO and rhEPO by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting. Samples were stained with a biotinylated monoclonal antibody against hEPO using horseradish peroxidase–labeled streptavidin and a chemiluminescent substrate. (A) Lane 1: molecular weight (MW) markers. Lane 2: epoetin alfa (1 ng). Lane 3: human serum EPO (1 ng). (B) Lane 1: molecular weight markers. Lane 2: human serum EPO (1 ng) after incomplete digestion with PNGase F. Lane 3: epoetin alfa (5 ng) after incomplete digestion with PNGase F. (C) Lane 1: epoetin alfa (5 ng) after incomplete digestion with PNGase F. Lane 2: epoetin alfa (5 ng) after complete digestion with PNGase F. Lane 3: human serum EPO (2 ng) after complete digestion with PNGase F (⇓O-glycosylated EPO; ⇑ non–O-glycosylated EPO). Lane 4: molecular weight markers. (D) Lane 1: fully glycosylated epoetin alfa (5 ng). Lane 2: epoetin alfa (10 ng) after treatment withArthrobacter ureafaciens sialidase. Lane 3: molecular weight markers.

SDS-PAGE with subsequent immunoblotting of human serum EPO.

Separation of human serum EPO and rhEPO by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting. Samples were stained with a biotinylated monoclonal antibody against hEPO using horseradish peroxidase–labeled streptavidin and a chemiluminescent substrate. (A) Lane 1: molecular weight (MW) markers. Lane 2: epoetin alfa (1 ng). Lane 3: human serum EPO (1 ng). (B) Lane 1: molecular weight markers. Lane 2: human serum EPO (1 ng) after incomplete digestion with PNGase F. Lane 3: epoetin alfa (5 ng) after incomplete digestion with PNGase F. (C) Lane 1: epoetin alfa (5 ng) after incomplete digestion with PNGase F. Lane 2: epoetin alfa (5 ng) after complete digestion with PNGase F. Lane 3: human serum EPO (2 ng) after complete digestion with PNGase F (⇓O-glycosylated EPO; ⇑ non–O-glycosylated EPO). Lane 4: molecular weight markers. (D) Lane 1: fully glycosylated epoetin alfa (5 ng). Lane 2: epoetin alfa (10 ng) after treatment withArthrobacter ureafaciens sialidase. Lane 3: molecular weight markers.

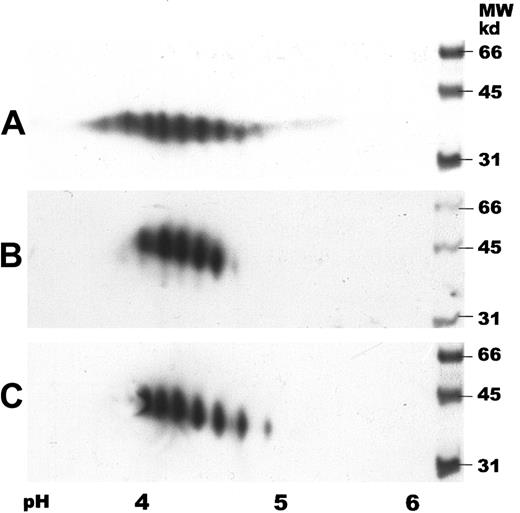

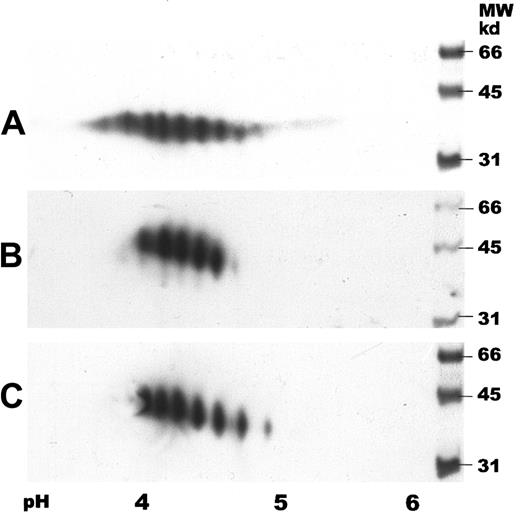

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis of human serum EPO.

IEF was carried out by using IPG strips with a pH gradient of 3 to 6. SDS-PAGE was performed in 12% gels followed by immunoblotting. Samples were detected with a biotinylated monoclonal antibody against hEPO using horseradish peroxidase–labeled streptavidin and a chemiluminescent substrate. (A) Human serum EPO (65 ng). (B) Epoetin alfa (50 ng). (C) Epoetin beta (50 ng).

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis of human serum EPO.

IEF was carried out by using IPG strips with a pH gradient of 3 to 6. SDS-PAGE was performed in 12% gels followed by immunoblotting. Samples were detected with a biotinylated monoclonal antibody against hEPO using horseradish peroxidase–labeled streptavidin and a chemiluminescent substrate. (A) Human serum EPO (65 ng). (B) Epoetin alfa (50 ng). (C) Epoetin beta (50 ng).

Binding of human serum EPO to the magnetic beads was also demonstrated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting, revealing human serum EPO as a broad immunostained band with a molecular size slightly, but significantly, smaller than the size of rhEPO (Figure 4A). The bandwidth of the monomer indicated microheterogeneity of human serum EPO. Apparent molecular weights of rhEPO (epoetin alfa) and human serum EPO, as revealed by SDS- PAGE, were found to be 40 kd and 34 kd, respectively (Figure 4A, lanes 2 and 3). Epoetin alfa and epoetin beta showed similar migration on SDS-PAGE (data not shown).

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis of human serum EPO with subsequent immunoblotting showed several spots with isoelectric points (pI) between 3.5 and 5, revealing both charge and size heterogeneity (Figure5A). Human serum EPO demonstrated a wider spectrum of spots than rhEPO with additional acidic and basic forms. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis of epoetin alfa and beta demonstrated different charge patterns with 5 and 6 major spots, respectively (Figure 5A-C).

Characterization of oligosaccharide structures from human serum erythropoietin

Determination of charge state.

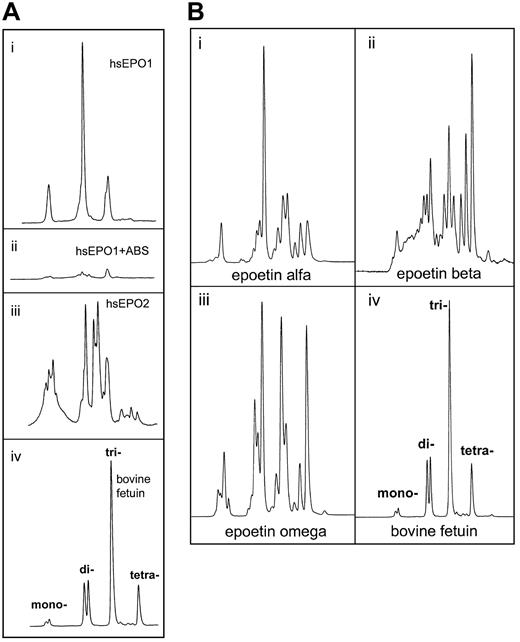

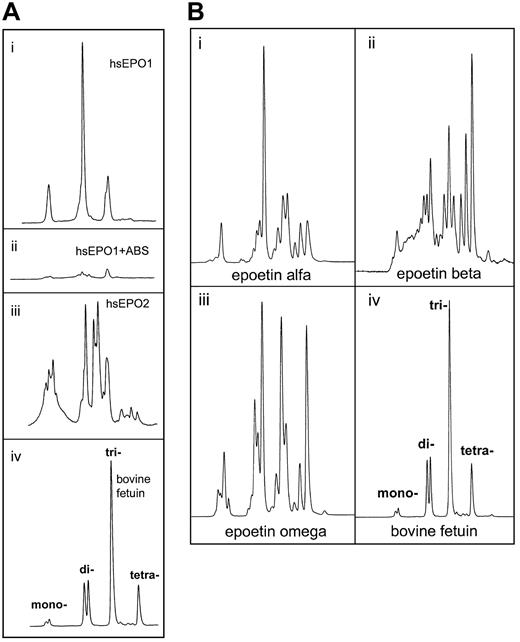

Charge analyses of 2-AB–labeled N-glycans from different species of hEPO are shown in Figure 6A-B, and the distribution is summarized in Table1. Neutral sugars were eluted at the start of chromatography and were, in this system, well separated from excess label (data not shown). Charge analyses demonstrated a higher content of neutral sugar in human serum EPO than in rhEPO (Table 1). The distribution of neutral compared to acidic sugars was determined by a stepwise gradient on GlycoSep C (data not shown).

Charge determination of oligosaccharides from human serum EPO.

Determination of charge state for the oligosaccharide structures from human serum EPO and rhEPO was demonstrated by weak anion exchange chromatography based on the method of Guile et al.42Classes of charged N-glycans, named mono-, di-, tri-, and tetra-acidic structures, were assigned by comparison with standard bovine fetuin sugars released and labeled in the same way.43-45 (A) Panels Ai and Aii represent charged 2-AB glycans from human serum EPO from a patient with aplastic anemia before (Ai) and after (Aii) digestion with Arthrobacter ureafacienssialidase. Panel Aiii: 2-AB glycans from another patient with aplastic anemia. Panel Aiv: 2-AB glycans from bovine fetuin (20 pmol). (B) Panel Bi: 2-AB glycans from epoetin alfa (20 pmol). Panel Bii: 2-AB glycans from epoetin beta (20 pmol). Panel Biii: 2-AB glycans from epoetin omega (20 pmol). Panel Biv: 2-AB glycans from bovine fetuin (20 pmol).

Charge determination of oligosaccharides from human serum EPO.

Determination of charge state for the oligosaccharide structures from human serum EPO and rhEPO was demonstrated by weak anion exchange chromatography based on the method of Guile et al.42Classes of charged N-glycans, named mono-, di-, tri-, and tetra-acidic structures, were assigned by comparison with standard bovine fetuin sugars released and labeled in the same way.43-45 (A) Panels Ai and Aii represent charged 2-AB glycans from human serum EPO from a patient with aplastic anemia before (Ai) and after (Aii) digestion with Arthrobacter ureafacienssialidase. Panel Aiii: 2-AB glycans from another patient with aplastic anemia. Panel Aiv: 2-AB glycans from bovine fetuin (20 pmol). (B) Panel Bi: 2-AB glycans from epoetin alfa (20 pmol). Panel Bii: 2-AB glycans from epoetin beta (20 pmol). Panel Biii: 2-AB glycans from epoetin omega (20 pmol). Panel Biv: 2-AB glycans from bovine fetuin (20 pmol).

Human serum EPO and rhEPO contained several acidic oligosaccharide structures (Figure 6A-B). Charge distribution analyses of the 2-AB glycan pools revealed unique patterns for all the hEPO species. The most important difference between circulating hEPO and rhEPO was the lack of tetra-acidic oligosaccharide structures in human serum EPO (Figure 6Ai, iii). Glycans from epoetin alfa, beta, and omega all contained such structures (Figure 6Bi-iii). In epoetin beta, tetra-acidic glycans was the dominating structure (Figure 6Bii). Deficiency of tetra-acidic structures in circulating hEPO oligosaccharides was shown for both sera from anemic patients analyzed in this study (Figure 6Ai, iii).

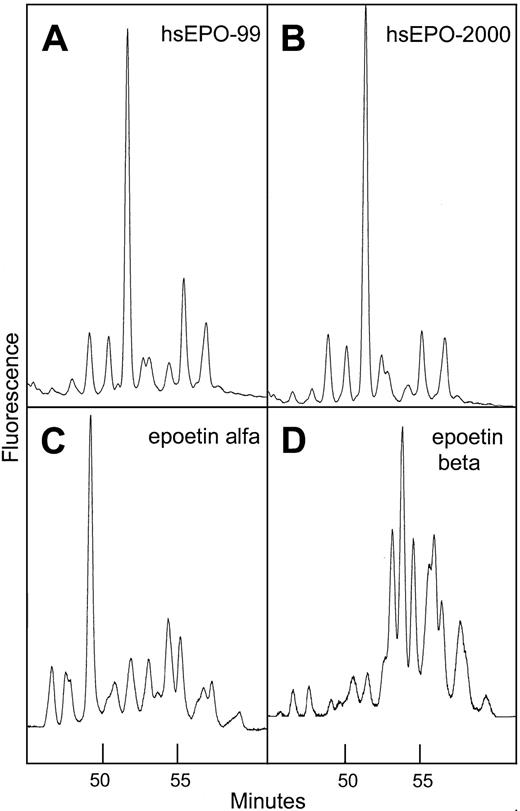

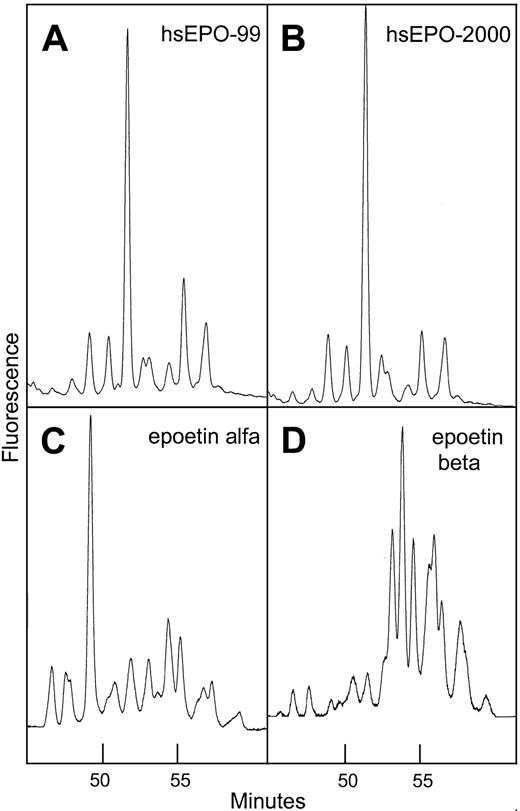

Sugar profiling of human serum erythropoietin.

When 2-AB–labeled glycans from different hEPO species were separated by normal-phase chromatography, they resolved into at least 11 peaks depending on which EPO species was analyzed. Each peak represented a specific oligosaccharide structure.39 46N-glycans from human serum EPO eluted at positions between the glycans from the different rhEPO species (Figure7).

Normal-phase HPLC profiles of human serum EPO and rhEPO.

Sugar profiling of 2-AB–labeled oligosaccharides from human serum EPO and rhEPO based on the method Guile et al.39 Panel A: 2-AB glycans from human serum EPO isolated from a serum sample taken in 1999 from a patient with aplastic anemia. Panel B: same as panel A, sample taken 1 year later. Panel C: 2-AB glycans from epoetin alfa. Panel D: 2-AB glycans from epoetin beta.

Normal-phase HPLC profiles of human serum EPO and rhEPO.

Sugar profiling of 2-AB–labeled oligosaccharides from human serum EPO and rhEPO based on the method Guile et al.39 Panel A: 2-AB glycans from human serum EPO isolated from a serum sample taken in 1999 from a patient with aplastic anemia. Panel B: same as panel A, sample taken 1 year later. Panel C: 2-AB glycans from epoetin alfa. Panel D: 2-AB glycans from epoetin beta.

Comparison of sugar profiles from human serum EPO, epoetin alfa, and epoetin beta revealed significant variation in elution times indicating unique glycosylation patterns. The profile of human serum EPO contained one large structure eluting later than the dominant peak in epoetin alfa (Figure 7). It was also demonstrated that the major part of the oligosaccharide structures from epoetin beta was larger and/or more acidic than the glycans from human serum EPO and epoetin alfa. Sugar profiles obtained from 2 batches of epoetin beta produced at different times appeared identical, which is consistent with a constant glycosylation pattern of hEPO expressed in CHO cells grown under standard conditions (data not shown). Sugar profiles of isolated human serum EPO taken from an anemic patient at different time intervals over a 1-year period were similar, indicating constant glycosylation (Figure 7A-B).

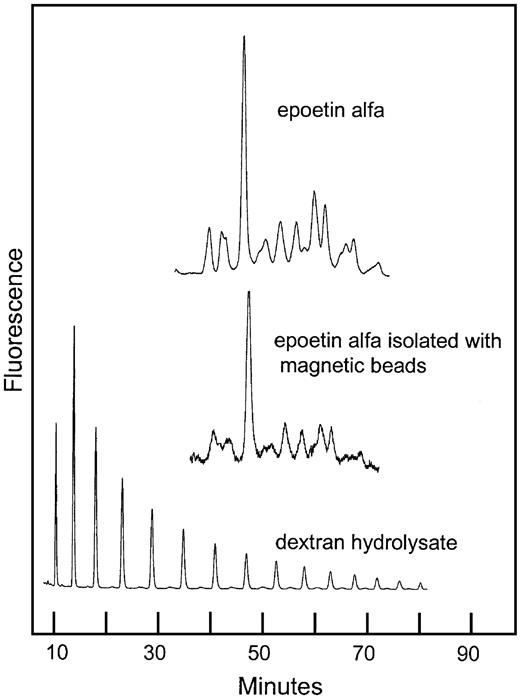

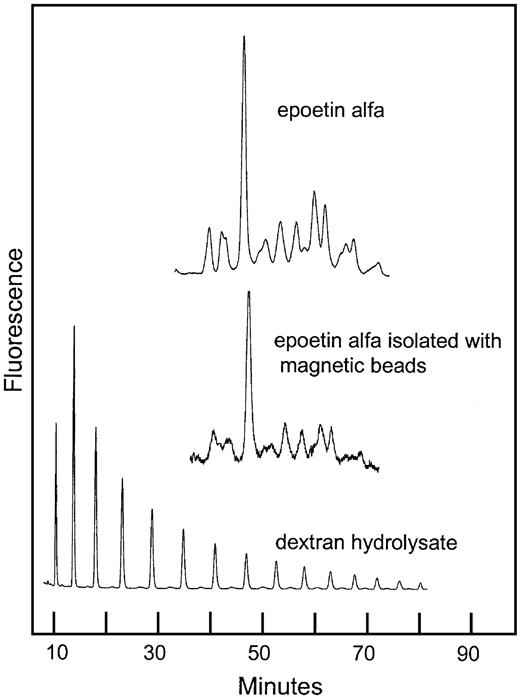

The ability of the hEPO-specific magnetic beads to bind a representative selection of the rhEPO glycoforms was demonstrated by the similarity of the sugar profiles from rhEPO with or without a bead-extraction step (Figure8).

Normal-phase HPLC of 2-AB–labeled oligosaccharides from rhEPO isolated with hEPO-specific magnetic beads.

Comparison of sugar profiles from epoetin alfa with and without immunomagnetic extraction. The column was calibrated using a 2-AB–labeled dextran hydrolysate (mixture of glucose oligomers).

Normal-phase HPLC of 2-AB–labeled oligosaccharides from rhEPO isolated with hEPO-specific magnetic beads.

Comparison of sugar profiles from epoetin alfa with and without immunomagnetic extraction. The column was calibrated using a 2-AB–labeled dextran hydrolysate (mixture of glucose oligomers).

Assignment of glycan structures from human serum erythropoietin by enzymatic digestion.

Preliminary structural assignments of human serum EPO glycans were performed using the 2 glycosidase enzymes (N-glycosidase and sialidase) with subsequent analyses either on SDS-PAGE using the whole hEPO glycoprotein or by normal-phase HPLC of the 2-AB–labeled oligosaccharides. Deglycosylation experiments showed that theN-linked oligosaccharides from human serum EPO were more susceptible to digestion by PNGase F than the N-glycans from rhEPO. The partial digestion pattern revealed in Figure 4B was obtained after 30 minutes' incubation for human serum EPO (lane 2) and 6 hours' digestion for rhEPO (lane 3). Complete release of the glycans was verified by SDS-PAGE (Figure 4C).

Complete de–N-glycosylation of human serum EPO and rhEPO resulted in similar mobility on SDS-PAGE (Figure 4C, lanes 2 and 3), demonstrating that the size difference of the fully glycosylated forms was caused by variations in theirN-linked oligosaccharide structures.

The broad band of human serum EPO revealed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting was in the same system resolved into 2 distinct bands by complete digestion with PNGase F (Figure 4C, lane 3). The upper band (21 000 kd) corresponded in size to O-glycosylated EPO, and the minor bottom band (below 20 000 kd) to non-O-glycosylated hEPO. Epoetin alfa appeared with only one band after digestion with PNGase F, corresponding toO-glycosylated EPO (Figure 4C, lane 2).

Partial de-N-glycosylation of human serum EPO with PNGase F was demonstrated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting (Figure 4B, lane 2) revealing 4 immunostained bands probably corresponding to zero, one, two, and three N-linked groups. The significantly smaller size observed for the incompletely digested glycoforms of human serum EPO, compared with the corresponding forms from epoetin alfa, were compatible with the size difference between the fully glycosylated forms (Figure 4A-B).

All acidic glycans released from human serum EPO were digested to neutral oligosaccharides by ABS as shown by chromatography on GlycoSep C, indicating that the charges were attributed to sialic acid (Figure 6Ai-ii). Sugar profiling of human serum EPO after treatment with ABS confirmed the existence of several sialylated oligosaccharide structures (data not shown).

SDS-PAGE of rhEPO after digestion with ABS revealed a decrease in its molecular size (Figure 4D), consistent with results from the 2-dimensional gel analyses showing that the basic glycoforms are smaller than the acidic forms (Figure 5A-C).

Discussion

In the current study, hEPO was isolated from the sera of anemic patients and was analyzed with respect to electrophoretic properties, glycosylation, and oligosaccharide structures. Previously, only the urinary species of endogenous hEPO had been isolated and characterized.7,47 The structural elucidation of circulating human serum EPO—the physiologically active form of EPO—is vital for our knowledge of its circulatory half-life and mechanism of action. Increasing clinical use of rhEPO also emphasizes the importance of structural comparison with human serum EPO for the understanding of its pharmacodynamics. Furthermore, the known misuse of rhEPO in sports renders the ability to detect significant molecular differences between endogenous hEPO and rhEPO important.6 48-52

Previous investigations have suggested the existence of several glycoforms of serum EPO in human and murine sera.53-57 In the current study, sugar profiling was used to scan the overall glycosylation of hEPO as synthesized by different cell types. Normal-phase HPLC confirmed the differences in glycosylation for human serum EPO and rhEPO detected by gel-electrophoretic methods and established that both are expressed as a population of many different glycoforms. The discrepancy in the glycosylation patterns for the various hEPO species is in agreement with other studies showing that glycoproteins synthesized by different cell systems display unique repertoires of oligosaccharides.58,59 Dissimilarities in glycosylation patterns have also been demonstrated for human urinary EPO and rhEPO.8,9 60-62

The observed size reduction of human serum EPO after de-N-glycosylation confirmed the presence ofN-linked oligosaccharides.63,64 In addition, the resultant 4 immunostained bands obtained after partial de-N-glycosylation of circulating hEPO were in accordance with three N-linked glycan structures per molecule, as previously reported for urinary and rhEPO.7-9,15 60

Specific N-linked glycan structures are probably the cause of the observed molecular weight difference between fully glycosylated human serum EPO and rhEPO because this difference was eliminated by complete de-N-glycosylation. TheO-glycosylated forms apparently obtained the same molecular weight after digestion with N-glycosidase, indicating that the O-linked glycan structures may be similar in the 2 hEPO species. The size difference between the partially digested forms of the 2 hEPO species were compatible with the difference between their fully glycosylated forms, indicating structural discrepancies in all 3N-linked sugar groups.

The lower band appearing on SDS-PAGE after complete de-N-glycosylation of human serum EPO probably represents fully deglycosylated EPO.16,65,66 The apparent molecular weight corresponded to approximately 18 kd, which is the calculated molecular weight of the polypeptide backbone of hEPO based on the cDNA sequence.4,5 The current demonstration of non-O-glycosylated forms in human serum EPO have previously been reported only for rhEPO expressed in BHK and COS-1 (kidney cells from African green monkey) cell systems.65-68 By the analysis of epoetin alfa, only forms containing O-linked sugars were detected after digestion with N-glycosidase, which is supported by previous analyses of rhEPO from CHO cells.69 SDS-PAGE of urinary hEPO after de-N-glycosylation15 showed onlyO-glycosylated forms of EPO. The proteins, however, were detected with Coomassie staining, which is less sensitive than the immunostaining procedures used today.

The observed mono-, di-, and tri-acidic charges of the oligosaccharides from human serum EPO are probably provided by terminal sialic acids, as demonstrated by charge analysis after sialidase treatment.43-45 Furthermore, this shows that sulfation, a common modification of the sugars on the glycoprotein hormones,70 is not an important contributor to the charge of circulating hEPO.

Recombinant hEPO appeared on SDS-PAGE with a small size reduction after de-sialylation, which is in agreement with other studies.62,67,69,71 Two-dimensional electrophoresis of hEPO also showed that the molecular sizes of the glycoforms increase when they are more acidic, probably because of terminal sialylation. These observations corresponded with the lower molecular weight observed for fully glycosylated human serum EPO compared with rhEPO, suggesting less sialylation of endogenous hEPO. Results from the charge analysis supported this, demonstrating a higher content of neutral sugar in circulating hEPO. Tsuda et al8 reported that rhEPO had a higher content of sialic acids than urinary hEPO from patients with aplastic anemia. However, some disagreement exists concerning this issue.14,60,62 72

In addition to charge heterogeneity, human serum EPO showed mass heterogeneity, revealed by the vertical shape of the spots in the 2-dimensional analysis, indicating that structural alterations among the oligosaccharides other than sialylation could contribute to the glycoform diversity of circulating hEPO.

Several IEF analyses of human serum EPO, urinary hEPO, and rhEPO display different conclusions.15,26,52,55,73,74 Tam et al55 analyzed serum from anemic patients by IEF demonstrating charge patterns similar to those in the current study, whereas Sohmiya and Kato74 recently showed that normal human serum after IEF contained 4 more basic forms of EPO. Although these discrepancies could be attributed to the pathologic conditions of the patients, they may also reflect variations within or between healthy persons.

The significantly higher susceptibility to de-N-glycosylation of circulating hEPO when compared to rhEPO also suggested conformational dissimilarities between the 2 hEPO species.

The most prominent difference between human serum EPO and rhEPO is the lack of tetra-sialylated oligosaccharide structures in circulating hEPO, as shown by charge analysis of the 2-AB–labeled glycans. According to results from the charge analysis, rhEPO had a relatively high content of tetra-sialylated oligosaccharide structures (epoetin alfa, 19%; epoetin beta, 46%; epoetin omega, 21%) in contrast to circulating hEPO, in which fully sialylated tetra-antennary glycans could not be detected. The charge distribution within epoetin beta revealed in this study is consistent with previous reports also demonstrating a high content of tetra-sialylated glycans.27,30,75,76 Kanazawa et al27 showed minor batch-to-batch variation in the expression of epoetin beta in CHO cells. Charge profiles of epoetin beta were constant over a period of 10 years.27 This is in accordance with the results from the current study, in which charge patterns of epoetin beta from 2 different sources were identical to the pattern published by those authors. It was also observed that the charge distribution and the sugar profile of human serum EPO glycans from an anemic patient were unchanged after 1 year, indicating that the glycosylation of circulating hEPO is constant.

Terminal sialic acids increase the circulatory half-life of glycoproteins in general and are crucial with respect to in vivo bioactivity of hEPO.11,77-80 Asialo–hEPO is rapidly cleared from the circulation by the galactose-receptor in the liver and has, therefore, no in vivo bioactivity. Several reports on endogenous hEPO have shown that circulating hEPO contains fewer acidic glycoforms than urinary hEPO.55,57 Wide et al57 also showed that rhEPO secreted in the urine is more acidic than rhEPO analyzed from serum of the same subject and concluded that the charge difference could be attributed to a difference in renal handling of the various glycoforms of hEPO, indicating a reabsorption of certain glycoforms. Several studies15,60,81 have demonstrated that the apparent molecular weight of purified urinary hEPO on SDS-PAGE is similar to that of rhEPO. A more recent paper62 reported urinary hEPO to be smaller. The sialic acid content of urinary hEPO, which has a strong influence on its acidity, however, was higher. In the current study, human serum EPO emerged with a significantly lower molecular weight than rhEPO, probably because of less extensive sialylation and other alterations in the glycan structures. Taken together, these findings may indicate structural differences between the serum and the urinary forms of hEPO caused by differential renal reabsorption or postsecretion processing of the glycans.

The deficiency of tetra-sialylated glycans in circulating hEPO may represent the normal glycosylation pattern of human serum EPO. The current sugar profiles of circulating hEPO could, however, reflect an abnormal condition in the renal cells synthesizing this hormone because tetra-sialylated oligosaccharide structures have been demonstrated in urinary hEPO in some studies.9 60

In this study, sera were obtained from 2 patients with aplastic anemia with very high concentrations of circulating EPO (approximately 7000 U/L and 20 000 U/L). The correspondingly increased rate of EPO synthesis could have resulted in impaired glycosylation, leading to changes in the sugar content of EPO.25 Accordingly, the lack of fully sialylated tetra-antennary oligosaccharide structures and the higher proportion of neutral glycans might have resulted from a shift in the glycosylation mechanism because of the pathologic condition of each patient. Changes in the glycosylation pattern may occur when the transit time through the glycosylation pathway is increased or decreased.25 Thus, the relative distribution of sialic acid within human serum EPO glycans seen in these patients might have resulted from the increased production rate of EPO caused by the anemic state. The resultant modified glycoform population of circulating EPO would lead to an increased breakdown because even a slight modification of the terminal sialic acids reduces the half-life of hEPO to a few minutes.11 Induced changes in the glycosylation process of the peritubular renal cells may suggest a physiological mechanism to increase the degradation of EPO in relation to pathologic high concentrations.

Sugar profiling of glycoproteins with regard to pathologic conditions has lately been a subject of much interest.40,82-85 Glycans as markers for diagnosis of specific autoimmune inflammatory diseases based on the glycosylation pattern of IgG have been reported.84,86 Diseases caused by inherited or acquired glycoprotein oligosaccharide structural alterations have also been described.85 The list of diseases caused by abnormal protein glycosylation is growing steadily, which may provide insight into their etiologies.

In conclusion, the current investigation revealed significant differences in the nature of the oligosaccharides on EPO from sera of anemic patients when compared with rhEPO glycans, emphasizing the complete lack of tetra-sialylated structures as the main divergence between human serum EPO and the recombinant ones.

Recombinant hEPO was kindly provided by Janssen-Cilag (Eprex, epoetin alfa; Norway), Roche (Recormon/NeoRecormon, epoetin beta; Norway), and Kemofarmacija dd (Epomax, epoetin omega; Slovenia). We thank Dr Geir Tjonnfjord (National Hospital, University of Oslo, Norway) and Dr Terje Andersson (Aker University Hospital, Oslo, Norway) for the sera from anemic patients. We also thank Mette Borgen and Aase R. Turter for their skillful technical help.

Supported by the Norwegian Department for Cultural Affairs, the Norwegian Research Council, and the International Olympic Committee.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Venke Skibeli, Section for Doping Analysis, Hormone Laboratory, Aker University Hospital, 0514 Oslo, Norway; e-mail: venke.skibeli@ioks.uio.no.