Abstract

Although systemic virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses are of critical importance in controlling virus replication in individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1), little is known about this immune response in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. This study investigated the GI tract CTL response in a nonhuman primate model for HIV-1 infection, simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)–infected rhesus monkeys. Lymphocytes from duodenal pinch biopsy specimens were obtained from 9 chronically SIVmac-infected rhesus monkeys and GI tract lymphocytes were harvested from the jejunum and ileum of 4 euthanized SIVmac-infected rhesus monkeys. Lymphocytes were also assessed in GI mucosal tissues by in situ staining in histologic specimens. SIVmac Gag-specific CTLs were assessed in the monkeys using the tetramer technology. These GI mucosal tissues of chronically SIVmac-infected rhesus monkeys contained levels of CTLs comparable to those found in the peripheral blood and lymph nodes. The present studies suggest that the CD8+ CTL response in GI mucosal sites is comparable to that seen systemically in SIVmac-infected rhesus monkeys.

Introduction

Gastrointestinal (GI) tract pathology commonly occurs in individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). These patients often manifest clinical GI abnormalities, including nutrient malabsorption, malnutrition, diarrhea, and weight loss.1,2 Pathologic changes in GI tissues from HIV-infected individuals include inflammatory infiltrates, villus blunting, and crypt hyperplasia.3 A progressive loss of the CD4+ T lymphocytes in the GI tract is observed early following infection.4 5 Yet, although the infecting virus is ultimately responsible for these diverse manifestations of disease, little is known about the host immune response to the virus in this anatomic compartment.

Because virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) play a central role in containing HIV replication, there is a reason to suppose that these effector cells are important in controlling HIV spread in the GI tract. However, little has been done to evaluate this localized cellular response. Such basic information as the magnitude of the HIV-specific CTL response in the GI tract of infected individuals is unknown.

The simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)/rhesus monkey model has been a powerful animal model for studying the immunopathogenesis of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Investigators have recently begun using this model to explore T-cell immune responses to the AIDS virus in various mucosal tissues, including the GI tract.6 We have previously demonstrated that we can use the tetramer technology to evaluate and quantify virus-specific CTL responses in rhesus monkeys infected with SIV or the chimeric simian HIV. The present study was initiated to characterize the CTL response in the GI tract of SIV-infected monkeys, using the tetramer technology.

Materials and methods

Animals and viruses

Blood samples (EDTA anticoagulated), duodenal biopsies, and GI tissues were obtained from 4 naı̈ve rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) and 13 rhesus monkeys infected with uncloned SIVmac 251 for more than 12 months. All chronically SIVmac-infected animals investigated, which received duodenal biopsies, were clinically stable, with CD4 T-cell counts ranging from 500 to 1000 cells/mL whole blood and relatively low viral loads (< 2 × 104 copies RNA/mL). Endoscope-guided pinch biopsies from duodenum were performed as previously described.7 Up to 12 duodenal tissue samples were collected and transported in RPMI containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) on ice to the laboratory for immediate processing. GI segments (about 10 cm) from jejunum and ileum were obtained from 4 euthanized SIVmac-infected rhesus monkeys, transported in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 10% FCS on ice to the laboratory, and processed for enrichment of lymphocytes within less than 1 hour. The viral loads of the 4 euthanized SIVmac-infected rhesus monkeys ranged from 4.5 × 106 to 1.5 × 103 copies RNA/mL as previously described (3KI: 4.5 × 106 copies/mL; IPI: 4.0 × 106 copies/mL; 575: 1.2 × 105copies/mL; 297: 1.5 × 103 copies/mL).8 The absolute CD4+ T-cell counts of these 4 animals ranged from 192 to 640 CD4+ T cells/μL whole blood (3KI: 540 CD4+ T cells/μL; IPI: 210 CD4+ T cells/μL; 297: 640 CD4+ T cells/μL; 575: 192 CD4+ T cells/μL). All SIVmac-infected rhesus monkeys used in this study wereMamu-A*01+ as determined both by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–based major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I typing and by functional CTL assays as previously described.9 These animals were maintained in accordance with the guidelines of the Committee on Animals for the Harvard Medical School and the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (National Research Council, National Academic Press, Washington, DC, 1996).

Enrichment of lymphocytes from duodenal biopsies and purification of lymphocytes from intestinal epithelium and lamina propria

Lymphocytes from GI tissues were enriched according to procedures described previously.10,11 Briefly, intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) were isolated from intestinal segments by using EDTA and mechanical disruption. Lamina propria lymphocytes (LPLs) were isolated from remaining intestinal pieces by collagenase digestion. Pinch biopsy specimens were similarly treated with EDTA and collagenase, but cells derived from these specimens were pooled. Lymphocytes where then enriched by Percoll density gradient centrifugation.7

Staining and phenotypic analysis of p11C, C-M–specific CD8+ T lymphocytes

Soluble tetrameric Mamu-A*01/p11C, C-M complex was made as previously described.8 The tetramer was produced by mixing biotinylated Mamu-A*01/p11C, C-M complex with phycoerythrin (PE)–labeled ExtrAvidin (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO) or Alexa 488-labeled NeutrAvidin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) at a 4:1 molar ratio. The monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) used for this study were directly coupled to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), PE-Texas red (ECD), or allophycocyanin (APC). The following mAbs were used: anti-CD8α(Leu2a)-FITC (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA); anti-CD8αβ(2ST8-5H7)-ECD, anti-CD11a(25.3.1)-PE, anti-CD28(4B10)-PE, anti-CD45RA(2H4)-PE, anti-CD49d(HP2/1)-PE, and anti-HLA-DR(I3)-PE (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL); and anti-CD95(DX2)-PE (Caltag, Burlingame, CA). The mAb FN18, which recognizes rhesus monkey CD3, a gift from Dr D. M. Neville Jr (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), was directly coupled to APC. Annexin V coupled to FITC (Beckman Coulter) was used to stain apoptotic lymphocytes. The 3 reagents, Alexa 488-coupled tetrameric Mamu-A*01/p11C, C-M complex, anti-CD8αβ-ECD, and anti–rhesus monkey CD3-APC were used either with anti-CD11a-PE, anti-CD28-PE, anti-CD45RA-PE, anti-CD49d-PE, anti-CD95-PE, or anti-HLA-DR-PE to perform 4-color flow cytometric analyses. The PE-coupled tetrameric Mamu-A*01/p11C, C-M complex was used with anti-CD8α-FITC in conjunction with anti-CD8αβ-ECD and anti–rhesus monkey CD3-APC. Alexa 488- or PE-coupled tetrameric Mamu-A*01/p11C, C-M complex (0.5 μg) was used in conjunction with the directly labeled mAbs to stain either 100 μL fresh whole blood or 5 × 105 single cells isolated from GI tissues or 5 × 105 lymphocytes isolated by density gradient centrifugation over Ficoll-Hypaque following in vitro culture. Samples were analyzed on a Coulter EPICS Elite ESP as described previously. Data presentation was performed using WinMDI software version 2.8 (Joseph Trotter, La Jolla, CA) and Microsoft PowerPoint 97 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

Confocal microscopy

In situ tetramer staining was performed on fresh tissues as previously described with some modifications.12 13Briefly, intestinal tissues collected at necropsy were washed in cold PBS and cut into small strips, which were further sectioned, on a vibrating microtome at 100 μm. The resulting sections (n = 4-6) were then incubated with 10 μL/section of the same Mamu-A*01/p11C, C-M tetramer indicated above conjugated to APC and gently agitated at 37°C for 15 minutes. The tissue was then rinsed repeatedly at 37°C with PBS and then twice with ice-cold PBS prior to fixation with cold 2% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes. After additional washes, antibodies to CD3 (rabbit polyclonal; Dako, Carpinteria, CA) and CD8α(Leu2a)-FITC were applied singly or together for 1 hour. The tissues were then washed and incubated with antirabbit Alexa 488 (Molecular Probes) when using only anti-CD3 or antirabbit Alexa 568 when using both anti-CD3 and anti-CD8. Tissues were then washed, mounted on a glass slide with antifading medium (Vectashield, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and examined by confocal microscopy.

Confocal microscopy was performed using a Leica TCS SP laser scanning microscope equipped with 3 lasers (Leica Microsystems, Exton, PA). Individual optical slices represent 0.2 μm and 32 to 62 optical slices were collected at 512 × 512 pixel resolution. The fluorescence of individual fluorochromes was captured separately in sequential mode, after optimization to reduce bleed-through between channels (photomultiplier tubes) using Leica software. NIH-image v1.62 and Adobe Photoshop v5 software were used to assign colors to each fluorochrome and the differential interference contrast image (gray scale). Colocalization of antigens is indicated by the addition of colors as indicated in the figure legends.

Cytotoxicity assay

Autologous B-LCL were used as target cells and were incubated with 5 μg/mL p11C, C-M (CTPYDINQM) or the negative control peptide p11B (ALSEGCTPYDIN) (single-letter amino acid codes) for 90 minutes during 51Cr labeling. For effector cells, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or single cells isolated from GI tissues of 4 monkeys chronically infected with SIVmac were cultured for 3 days in the presence of 5 μg/mL concanavalin A (Con A) at a density of 3 × 106 cells/mL, and then maintained for another 7 to 11 days in medium supplemented with recombinant human interleukin-2 (IL-2) (20 U/mL; provided by Hoffman-La Roche, Nutley, NJ). PBMCs or GI lymphocytes were centrifuged over Ficoll-Hypaque (Ficopaque; Pharmacia Chemical, Piscataway, NJ) and assessed after in vitro culture in a standard 51Cr release assay using U-bottom microtiter plates containing 104 target cells with effector cells at different E/T ratios. All wells were established and assayed in duplicate. Plates were incubated in a humidified incubator at 37°C for 4 hours. Specific release was calculated as (experimental release − spontaneous release)/(maximum release − spontaneous release) × 100. Spontaneous release was less than 20% of maximal release with detergent (1% Triton X-100, Sigma Chemical) in all assays.

Results

The majority of GI T lymphocytes from SIVmac-infected rhesus monkeys express the CD8 molecule

Lymphocytes were isolated from duodenal pinch biopsy specimens from 4 naı̈ve and 9 SIVmac-infected rhesus monkeys. As previously described,7,14 15 we found that the lymphocyte populations in GI tissues of SIVmac-infected rhesus monkeys comprised a large percentage of CD8+ T cells compared to those of naı̈ve animals (data not shown). A median of 99% of the jejunal and ileal T lymphocytes in the intraepithelial mucosa from 4 euthanized SIVmac-infected rhesus monkeys expressed the CD8 molecule. A slightly lower fraction of T cells were CD8+ in the lamina propria from jejunum (median of 90%) and ileum (median of 93%) (data not shown).

Duodenal and peripheral blood CD8+T lymphocytes from SIVmac-infected rhesus monkeys comprise a comparable fraction of tetramer-binding cells

Lymphocytes isolated from duodenal biopsy specimens from 9 SIVmac-infected rhesus monkeys were assessed for tetramer-binding CD8+ T cells (Table1). The mechanical disruption and enzymatic digestion used to isolate these cells did not interfere with the ability of the cells to bind antibodies.10 A median of 4.2% and 7.9% of CD8+ T cells in peripheral blood and duodenum, respectively, bound the tetramer. These differences did not achieve statistical significance (P = .3; Wilcoxon matched pairs test).

LPLs from SIVmac-infected rhesus monkeys contain a higher percentage of tetramer-binding CD8+T cells than IELs

Lymphocytes were isolated from the ileum and jejunum of the 4 euthanized SIVmac-infected rhesus monkeys and separated into IEL and LPL populations. Staining these cell populations with mAbs and tetramer and analyzing the cells by flow cytometry demonstrated that IELs from the ileum and jejunum contained a lower percentage of tetramer-binding CD8+ T lymphocytes than did lymphocytes from peripheral blood or LPLs (statistical analysis of the combined results from ileum and jejunum: P = .0078; Wilcoxon matched pairs test). However, the percentage of tetramer-binding CD8+ T lymphocytes in the peripheral blood was not significantly different from the percentage of tetramer-binding lymphocytes in the LPLs from the ileum and jejunum (statistical analysis of the combined results from ileum and jejunum:P = .74; Wilcoxon matched pairs test; Table2). These results were confirmed when we performed in situ tetramer staining on fresh tissues (Figure1). The lamina propria contained more lymphocytes than the epithelium in these tissues. We could easily identify tetramer-binding cells in the lamina propria, but found only very occasionally tetramer-binding IELs.

In situ tetramer staining of GI tissue by confocal microscopy.

Images for individual channels (CD3, green; SIV Gag tetramer, red; differential interference contrast [DIC], gray scale) are shown on the left side and a larger merged image containing all 3 channels is shown on the right. Several CD3+ cells are present in the lamina propria of a small intestinal villous, one of which is also labeled with the SIV Gag tetramer. Bar = 10 μM.

In situ tetramer staining of GI tissue by confocal microscopy.

Images for individual channels (CD3, green; SIV Gag tetramer, red; differential interference contrast [DIC], gray scale) are shown on the left side and a larger merged image containing all 3 channels is shown on the right. Several CD3+ cells are present in the lamina propria of a small intestinal villous, one of which is also labeled with the SIV Gag tetramer. Bar = 10 μM.

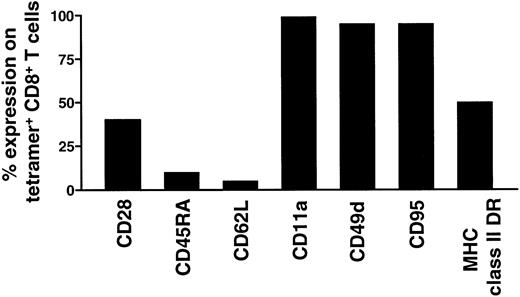

Tetramer-binding GI CD8+ T lymphocytes have an activated phenotype

Cell staining with mAb and tetramer and 4-color flow cytometric analysis was performed to evaluate the phenotypic profile of tetramer-binding GI lymphocytes. Consistent with our previous findings in studies of tetramer-binding CD8+ T lymphocytes in the peripheral blood and lymphatic tissues of chronically SIVmac-infected rhesus monkeys,8,9 16-18 we observed that the tetramer-binding CD8+ IELs or LPLs from the ileum and jejunum had a phenotypic appearance consistent with their being activated. An example of a phenotypic analysis of tetramer-binding CD8+ jejunal LPLs is shown in Figure2. Almost all of the tetramer-binding CD8+ T lymphocytes associated with the GI tracts of these monkeys expressed high levels of the adhesion molecules CD11a, CD49d, and the activation-associated molecule CD95. A substantial percentage of the tetramer-binding CD8+ T cells expressed the activation-associated molecule HLA-DR (range, 37%-70%). Only a very small subset of the tetramer-binding CD8+ T cells expressed CD45RA and CD62L, molecules associated with functionally naı̈ve lymphocytes. Fewer than 50% of these tetramer-binding CD8+ T lymphocytes (range, 10%-45%) expressed the CD28 molecule.

Phenotypic characterization of tetramer-binding CD8αβ+ T lymphocytes.

Phenotype of lymphocytes isolated from LPLs and IELs of jejunum from the chronically SIVmac-infected rhesus monkey 251 are shown.

Phenotypic characterization of tetramer-binding CD8αβ+ T lymphocytes.

Phenotype of lymphocytes isolated from LPLs and IELs of jejunum from the chronically SIVmac-infected rhesus monkey 251 are shown.

Tetramer-binding GI tract-associated CD8+ T lymphocytes mediate SIVmac-specific cytotoxic activity

To evaluate the functional activity of the CD8+ T lymphocytes isolated from duodenal pinch biopsy specimens from these 4 SIVmac-infected rhesus monkeys, peripheral blood lymphocytes from the monkeys were stimulated with lectin and cultured in medium containing IL-2 in parallel with the duodenal lymphocyte populations. The percentage of tetramer-binding CD8+ T lymphocytes increased during this period of culture in 3 of the 4 peripheral blood lymphocyte populations (Table 3). However, a slightly decreased percentage of tetramer-binding CD8+ T lymphocytes was found following culture of the duodenal lymphocytes (Table 3). Standard 51Cr release assays were performed using as effector cells the cultured peripheral blood and duodenal lymphocyte populations obtained from 3 SIVmac-infected rhesus monkeys. All lymphocyte populations from the peripheral blood and duodenum mediated SIVmac Gag-specific CTL activity (Table 3).

Discussion

In the present study we have investigated SIVmac-specific CD8+ CTLs in GI tissues obtained from chronically SIVmac-infected rhesus monkeys. We found that SIVmac Gag-specific T lymphocytes were present in GI tissues obtained from duodenum, jejunum, and ileum at levels comparable to those found in peripheral blood. Thus, the frequency of these CTLs is comparable in peripheral blood, lymph nodes, and GI tissue of chronically SIVmac-infected rhesus monkeys.8,9,15,16 Interestingly, higher frequencies of CTLs have only been found in spleen, bone marrow, and liver of infected animals.8,9,15 16

Although HIV-1 and SIV-specific CTLs have previously been detected in lymphocytes isolated from mucosal tissues, a definitive localization of the HIV-1 or SIV-specific CTLs in mucosal tissues has never previously been achieved. In fact, some investigators have found a higher frequency of CTLs in IELs19,20 and others in LPLs.21 The introduction of the tetramer technology has now facilitated the localization of these cells. In the present study we found that both IELs and LPLs contain very high percentages of CD8+ T lymphocytes. Moreover, we observed that tetramer-binding CD8+ T lymphocytes are preferentially found in LPLs.

The specificity of the CD8+ T cells in IELs is not clear. However, a possible explanation for the relatively low frequency of tetramer-binding CD8+ T lymphocytes in IELs could be related to the fact that IELs contain only very small numbers of infected cells that may serve as targets for CTLs.

It is well established in studies of humans, monkeys, and mice that CD8+ T lymphocytes associated with the GI tract express a significant amount of the αα homodimeric rather than the heterodimeric CD8 molecule. However, previously it was demonstrated that the ratio of CD8αβ+ T cells to CD8αα+ T cells significantly increases in GI tissues following infection with the AIDS virus.22 In accordance with these results, we found that at least 90% of the tetramer-binding CD8+ T lymphocytes from the GI tissues expressed CD8αβ-heterodimer (data not shown). Only one animal (3KI)17 had a high frequency (30%) of CD8αα+ tetramer-binding CD8+ T lymphocytes in mucosal tissues.

Attempts to characterize the functional activity of mucosal CTLs have to date yielded inconsistent results. Some investigators have described increased levels of cytotoxicity-associated molecules (eg, granzyme B and T-cell–restricted intracellular antigen [TIA-1])23,24 in GI-associated CD8+T lymphocytes, whereas others found reduced levels of these molecules in GI lymphocytes.25 Functional cytotoxic activity specific for HIV-1 or SIV was recently observed in freshly isolated mucosal lymphocytes19 or after in vitro expansion of mucosal lymphocytes.19,26,27 However, functional cytotoxic activity was only found in lymphocytes from half of those patients whose peripheral blood lymphocytes mediated this activity.26 27 We were able to detect SIVmac Gag-specific CTL activity in mucosal lymphocyte populations following nonspecific expansion of the cells in vitro. We did, however, observe a slightly decreased ability to expand mucosal lymphocytes in vitro in contrast to peripheral blood lymphocytes. GI lymphocytes may be end-stage cells with a limited capacity to proliferate. However, it is also possible that the isolation procedures used for the enrichment of the GI lymphocytes may have resulted in an increased fragility of these cells. In fact, we found that 20% to 30% of the tetramer-binding CD8+ T lymphocytes from GI tissues of the infected monkeys bound annexin V, an indicator that these cells are undergoing a death process. In contrast, less than 3% of the freshly isolated tetramer-binding CD8+ T lymphocytes from peripheral blood bound annexin V (data not shown).

The results of the present study show that tetramer-binding CD8+ T lymphocytes can be found in GI tissues of chronically SIVmac-infected rhesus monkeys at levels comparable to those seen in peripheral blood. The procedures developed to carry out these studies will be useful to characterize SIV-specific immune responses in GI tissues in evaluating different HIV vaccine modalities in nonhuman primates.

The authors thank William A. Charini and Carol A. Lord for MHC class I typing of the monkeys used in this study.

Supported by US Public Health Service grants AI-20729 (to N.L.L.), AI48394 (to J.E.S.), and DK50550 and DK55510 (to A.A.L.), by the base grant RR00168 of the New England Regional Primate Research Center and by the DFCI/BIDMC/CH CFAR grant P30 AI28691 (to J.E.S.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Jörn E. Schmitz, Division of Viral Pathogenesis, Department of Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, RE-111, 41 Ave Louis Pasteur, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail: jschmitz@caregroup.harvard.edu.

![Fig. 1. In situ tetramer staining of GI tissue by confocal microscopy. / Images for individual channels (CD3, green; SIV Gag tetramer, red; differential interference contrast [DIC], gray scale) are shown on the left side and a larger merged image containing all 3 channels is shown on the right. Several CD3+ cells are present in the lamina propria of a small intestinal villous, one of which is also labeled with the SIV Gag tetramer. Bar = 10 μM.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/98/13/10.1182_blood.v98.13.3757/6/m_h82411894001.jpeg?Expires=1766068655&Signature=sJg6uw9H76eDJ1H5TaHBQnj~mdXVpXlan5gJnemMwBN0CfVoWhJsGZEgqt5aJcLuvApg3imCPbFoXgymc5rZCujkuaxTDWbmzjbakt144~KLWN2T8pPjEqirdAgGdkqH8USgR55m4Rigo0kP5XmcC1Og18NvOddKLIMTPI9v878DAYAxSjlj-WoQ-w-bZqqc94z4pP4vC7uu19qvNSuTFp5VnOs~8dH6RUWlOJNvfmdcux7m0Kd0PQogatCy5bsfNjPYV~JPIXBnoVvyehoHqRCcyIEVH9k9N4LJSp99VKLVFzEyWmFHd-FGRUzSOIHHN25-4rV-uXtvjUXIUm2mcA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)