It is demonstrated that similar to interferon γ (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) induces coordinated changes at different steps of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I processing and presentation pathway in nonprofessional antigen-presenting cells (APCs). TNF-α up-regulates the expression of 3 catalytic immunoproteasome subunits—LMP2, LMP7, and MECL-1—the immunomodulatory proteasome activator PA28α, the TAP1/TAP2 heterodimer, and the total pool of MHC class I heavy chain. It was also found that in TNF-α–treated cells, MHC class I molecules reconstitute more rapidly and have an increased average half-life at the cell surface. Biochemical changes induced by TNF-α in the MHC class I pathway were translated into increased sensitivity of TNF-α–treated targets to lysis by CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, demonstrating improved presentation of at least certain endogenously processed MHC class I–restricted peptide epitopes. Significantly, it was demonstrated that the effects of TNF-α observed in this experimental system were not mediated through the induction of IFN-γ. It appears to be likely that TNF-α–mediated effects on MHC class I processing and presentation do not involve any intermediate messengers. Collectively, these data demonstrate the existence of yet another biologic activity exerted by TNF-α, namely its capacity to act as a coordinated multi-step modulator of the MHC class I pathway of antigen processing and presentation. These results suggest that TNF-α may be useful when a concerted up-regulation of the MHC class I presentation machinery is required but cannot be achieved by IFN-γ.

Introduction

Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I pathway of antigen presentation constitutively acts in most somatic cells and represents a highly coordinated chain of events that includes ubiquitinylation and proteolytic processing of antigens, peptide translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) lumen by transporters associated with antigen processing (TAPs), and MHC class I complex assembly and transportation to the cell surface (for review, see1-4). The major source of peptides presented on MHC class I molecules is the pool of endogenously expressed antigens that includes cytosolic,5-7 nuclear, membrane-associated, or secretory proteins.8-11 Peptide fragments derived from self-proteins are usually ignored by the host immune system, whereas epitopes derived from foreign or mutated self-antigens trigger CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell (CTL) responses.

The proteasome is a major proteolytic complex participating in the generation of antigenic epitopes.2 It is composed of the proteolytic core (20S) and regulatory caps (19S), which assemble into the structure referred to as 26S complex. On interferon γ (IFN-γ) treatment, the 26S complex is reorganized into the immunoproteasome in which 3 catalytic subunits of the proteolytic core—β1i, β2i, and β5i—are substituted by LMP2, MECL-1, and LMP7, respectively (reviewed in York et al1 and Rock and Goldberg2). This exchange results in alterations in fine cleavage specificities: trypsinlike, chymotrypsinlike, and branched chain amino acid–preferring activities are stimulated, whereas peptidylglutamyl peptide–hydrolyzing activity is reduced.12-14 This promotes the production of peptides with basic or hydrophobic C-termini, stimulates better uptake by TAPs,15-18 and, therefore, facilitates MHC class I complex assembly in the ER. A role of the immunoproteasome in MHC class I–restricted presentation has been confirmed by a number of in vitro and in vivo studies that demonstrated an enhanced presentation of several MHC class I–restricted epitopes after the induction of immune proteasomal subunits.2,19 Besides the changes in the proteolytic core, IFN-γ induces expression of the PA28α regulatory subunit that correlates with enhanced presentation of certain MHC class I–restricted epitopes.20 Recent data suggest that the effect of PA28α on the antigen presentation may be dissociated from the induction of the immunoproteasome.19

It is well established that the presentation of most MHC class I–restricted epitopes is TAP dependent.18,21 Human TAP1/TAP2 heterodimers are permissive for peptides of 7 to 12 amino acids in length with basic or hydrophobic C-terminal residues,16,21,22 which are optimal for binding to MHC class I. The expression of both subunits of the TAP heterodimer is up-regulated by IFN-γ.23

IFN-γ also modulates a number of proteolytic enzymes involved in MHC class I–restricted presentation that are distinct from the proteasomal proteolytic subunits, facilitating the production of immunogenic peptide epitopes or preserving them from further degradation. These include leucine aminopeptidase24 and thimet oligopeptidase.2 25 At present, IFN-γ is the only immune modifier with firmly established capacity to facilitate the MHC class I antigen processing and presentation affecting different steps of the pathway.

In search for other immune modifiers capable of acting on the antigen presentation machinery, we focused on tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), another pleiotropic proinflammatory cytokine known to up-regulate MHC class I expression when used as a single agent or as a synergist of IFN-γ. However, the molecular basis of this effect was not investigated. It was observed that cells that underwent TNF-α treatment had an increased amount of LMP2 and di-ubiquitin mRNAs as detected by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).26 Another report showed a transcriptional up-regulation of LMP7 gene expression.27 However, the functional significance of these effects was not addressed. Noteworthy, the generation of the immunoproteasome requires coordinated incorporation and, hence, expression of both LMPs and of the MECL-1 subunits because these subunits are synthesized as catalytically inactive precursors that undergo autocleavage and acquire proteolytic function only after the proteasome assembly.28 29

In this study, cell lines of different tissue origins were used to assess the effect of TNF-α on the antigen presentation machinery. We focused our attention on melanoma cells because of several reasons. First, high-dose TNF-α administered regionally through isolated limb perfusion has proved to be a safe and efficient approach in the treatment of patients with melanoma, resulting in approximately 80% complete remissions of in transit melanoma metastases.30This effect is thought to result from the induction of apoptosis of intratumoral angiogenic endothelial cells through the deactivation of integrin αVβ3.30 However, the effect of TNF-α on the antigen presentation in melanoma cells was not investigated. Second, although TNF-α is known as a potent inducer of apoptosis in different types of cells,31-33 melanomas are resistant to TNF-α–mediated apoptosis.34 Therefore, changes in the antigen presentation machinery induced by TNF-α cannot be merely a reflection of cell progression through a death program.

Our results demonstrate that TNF-α is an immune modifier acting on the MHC class I processing and presentation pathway by inducing expression of the immune proteasome and TAPs and increasing the pool of long-lived MHC class I–peptide complexes at the cell surface.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

BL, AA, and 0505mel are melanoma cell lines derived from metastatic lesions of patients treated at Radiumhemmet, Karolinska Hospital and are established at the Microbiology and Tumorbiology Center of the Karolinska Institute. The 397 melanoma cell line was kindly provided by Dr Y. Kawakami (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD). The T2 cell line is a human T-cell leukemia/B-cell line hybrid, defective in TAP1/TAP2 and immunoproteasomal subunits.35Lymphoblastoid cell line (LCL) JAC-B2 was obtained by in vitro transformation of B cells from healthy donor by the B95.8EBV strain. Cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 (Gibco BRL, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Gibco BRL), 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (complete medium). The A42 is CD8+ CTL clone specific to human leukocyte antigen (HLA) A2–restricted, melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (MART-1)–derived peptide epitope 27-35.

Antibodies and chemicals

Proteasome subunit-specific antibodies (anti-LMP2, LMP7, MECL-1, PA28α, and anti-α2) were purchased from Affinity Research Products (Mamhead Castle, Exeter, United Kingdom). TAP1- and TAP2-specific antibodies were kindly provided by Dr J. Trowsdale (University of Cambridge, United Kingdom). Rabbit polyclonal serum specific to human class I heavy chain was a kind gift from Dr H. Ploegh (Department of Pathology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). HLA A, B, C (HLA ABC) allele-specific antibody (clone W6/32) conjugated with R-phycoerythrin was obtained from Dako A/S (Denmark). Brefeldin A (BFA) and actin-specific antibody were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Human recombinant TNF-α was obtained from Cetus (Emeryville, CA), and IFN-γ was from Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH (Ingelheim, Germany). TNF-α–specific blocking antibodies were purchased from R&D Systems (Abingdon, United Kingdom), and IFN-γ blocking antibodies were from Nordic Biosite (Täby, Sweden).

Western blot analysis

Expression of molecules involved in MHC class I–restricted antigen presentation was assessed by Western blot using the Multiphor II Electrophoresis System and ExelGel SDS Homogeneous precast gels (Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden). Cells cultured in complete medium (further referred to as control) or in the presence of TNF-α (30 ng/mL) or IFN-γ (500 IU/mL) for 48 hours at 37°C were pelleted down and lysed in electrophoresis sample buffer. Aliquots of total cell lysates corresponding to 105 cells were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore AB, Sundbyberg, Sweden). Membranes were blocked in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5% milk and 0.1% Tween-20 and were probed with the indicated specific antibody at the dilution recommended by the manufacturer. After incubation with the secondary antibody (antimouse for α2/MC6 subunit of the 20S complex and actin; antirabbit for TAP1, TAP2, class I heavy chain and LMP2, LMP7, MECL-1, and PA28α subunits of the proteasome) conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden), membranes were extensively washed, and the reaction was visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB). The intensity of specific bands was assessed by densitometry using DuoScan (AGFA) and Fotolook 32V3.00.00 software.

Cytokine blocking experiments

IFN-γ–blocking experiments.

Melanoma cell lines were treated with either IFN-γ (1 IU/mL) or TNF-α (30 ng/mL) alone or in the presence of IFN-γ–specific rabbit polyclonal antibodies at a concentration sufficient to neutralize 1 IU/mL or 5 IU/mL lymphokine. Corresponding amounts of the rabbit IgG, 20 ng/mL and 100 ng/mL, were used as control. After 48 hours, cells were collected and assessed for the expression of the HLA ABC at the cell surface by flow cytometry. The level of the MHC class I complexes in each sample was compared to that in untreated cells and expressed as a difference in mean fluorescence intensity.

TNF-α–blocking experiments.

Melanoma cell lines were treated either with TNF-α (30 ng/mL) alone or in the presence of 1 μg/mL or 2 μg/mL TNF-α–specific neutralizing goat polyclonal antibodies (amounts capable of blocking TNF-α at the concentration of 20 ng/mL or 40 ng/mL, respectively). Equal amounts of the isotype control goat IgG (1 μg/mL or 2 μg/mL) were used as control. After 48 hours, cells were assessed for the expression of the HLA ABC at the cell surface by flow cytometry. The level of MHC class I expression of each sample was compared to that of untreated cells, and the difference in mean fluorescence intensity was designated the MFI increase.

Cytotoxicity assay

Standard Cr-release assays were performed as previously described.36 Briefly, target cells either untreated or treated with different concentrations of TNF-α for 48 hours were labeled with Na51CrO4 (0.0037 MBq/106 [0.1 μCi/106] cells at 37°C for 1 hour). After extensive washing, target cells were incubated with effectors at 10:1, 5:1, and 2.5:1 effector-to-target ratios in triplicate for 4 hours at 37°C. Cr-release in the supernatants was measured in a gamma-counter (Wallac Sverige AB, Upplands Väsby, Sweden).

Stability of MHC class I complexes at the cell surface

Cells cultured in complete medium in the presence or absence of TNF-α (30 ng/mL, 48 hours) were removed from the plastic surface by a scraper, washed twice in ice-cold PBS, and exposed to BFA (10 μg/mL) in AIM-V medium (Gibco BRL). After 1-hour BFA treatment, cells were washed twice in PBS, and one aliquot was placed on ice (time zero). Remaining cells were incubated in AIM-V at 37°C, and aliquots were collected at indicated time points (1 hour, 2 hours, 3 hours, 4 hours, and 5 hours) and were kept on ice until termination of the experiment. All subsequent procedures were carried out on ice. Samples were stained with an excess of the W6/32 antibody specific for HLA ABC or isotype (IgG2a) antibody control, both directly conjugated with phycoerythrin. After extensive washing in ice-cold PBS, cells were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS and analyzed on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA).

Reappearance of MHC class I complexes at the cell surface

Reappearance rates of MHC class I complexes at the cell surface were monitored as previously described.37 Briefly, cells were incubated in a buffer containing 0.06 M sodium dihydrocarbonate and 0.113 M citric acid (pH 3.0) for 1 minute and were extensively washed in complete medium. An aliquot was collected and placed on ice (time zero sample). Remaining cells were incubated in complete medium at 37°C, and aliquots were collected at the indicated time points. Surface expression of HLA ABC was monitored as described above.

Detection of IFN-γ mRNA expression

Total RNA was extracted from control or TNF-α–treated (30 ng/mL during 48 hours) cells as previously described.38RNA (0.3 μg) from each sample was separated on ethidium bromide–stained 1% agarose gel. Optical density of the RNA bands was analyzed using a Kodak DC-40 digital camera and Kodak Digital Science 1D Image Analysis Software (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) to confirm the results of spectrophotometric measurements of RNA concentration and to exclude the RNA degradation and contamination of the samples with genomic DNA. For first-strand cDNA synthesis, the RNA was denatured for 5 minutes at 70°C and chilled on ice. Reverse transcription was performed in a 40-μL reaction containing 2 μg denatured RNA dissolved in 20 μL RNase-free water, 8 μL 5× buffer (Gibco BRL), 4 μL dNTP (5 mM each; Pharmacia), 3 μL 100 mM dithiothreitol (Gibco BRL), 1 μL RNasin (40 U/μL; Promega, Madison, WI), 2 μL 0.1 mM random hexamer primers (Pharmacia), and 2 μL M-MLV reverse transcriptase (200 U/μL; Gibco BRL). After 45-minute incubation at 40°C and heating at 95°C for 5 minutes to inactivate the reverse transcriptase, the samples were used directly for PCR reaction. One microliter cDNA was diluted with sterile water to 5 μL and mixed with 20 μL PCR mixture containing: 2.5 μL 10× buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl–500 mM KCl–0.1% gelatin, pH 8.3), 2 μL 25 mM MgCl2, 4 μL dNTP (1.25 mM each; Pharmacia), 2.5 μL each primer (5 μM), 6.375 μL sterile water, and 0.125 μL Taq polymerase (PerkinElmer, Boston, MA). The reaction mixture was amplified with a PTC-100 thermal cycler (MJ Research, Waltham, MA). Cycling conditions were 1 minute at 95°C for denaturation, 1 minute at 58°C for annealing, and 1 minute at 72°C for elongation. PCR reaction was terminated by 7-minute incubation at 72°C for final elongation. Serial dilutions of the template were performed with each primer set to establish the number of cycles required to reach the exponential phase of the amplification reaction (20 cycles for amplification of β2-microglobulin and 32 cycles for IFN-γ). The 5′- and 3′-specific cDNA primers—IFN-γ, 5′-TCTGCATCGTTTTGGGTTCT-3′ and 5′-CAGCTTTTCGAAGTCATCTC-3′; β2-microglobulin, 5′-GAATTGCTATGTGTCTGGGT-3′ and 5′-CATCTTCAAACCT CCATGATG-3′—were purchased from Biosource Europe (Fleurus, Belgium). PCR products were separated on 1.6% agarose gel (Eastman Kodak) and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Results

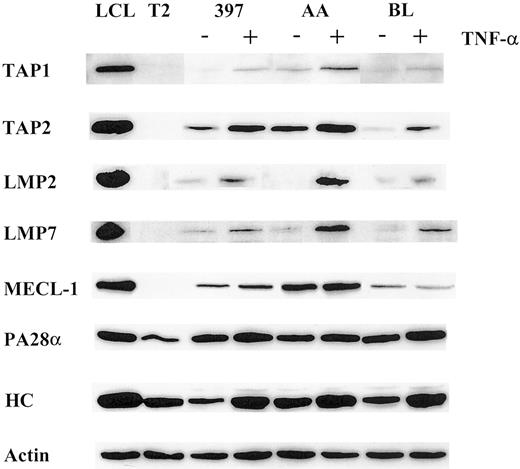

TNF-α up-regulates the expression of TAP1/TAP2, induces expression of the proteolytic and regulatory subunits of the immunoproteasome, and increases the amounts of MHC class I heavy chain in nonprofessional APCs

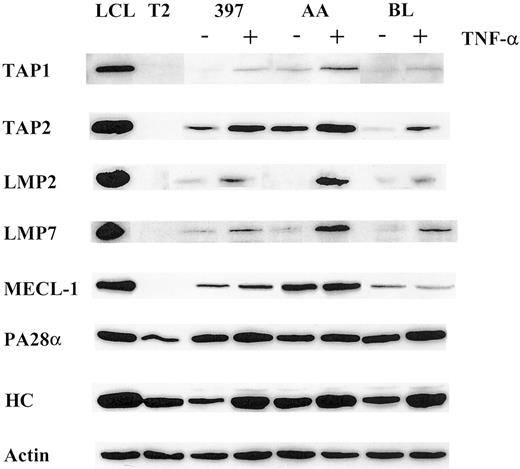

Using a panel of cell lines of different origins, we compared the effect of TNF-α on the expression of the LMP2, LMP7, and MECL-1 proteolytic subunits. Western blot analysis of AA, BL, and 397 melanoma cell lines (Figure 1) revealed that the LMP2 and LMP7 proteins were expressed at extremely low or, in some cases, undetectable levels, whereas TNF-α–treated samples of all 3 cell lines showed increased expression of these subunits. The MECL-1 protein was usually detected in tumor cells (Figure 1 and data not shown); however, its expression was also markedly increased after TNF-α treatment. Thus, the expression of all 3 known catalytic subunits of the immunoproteasome can be induced in tumor cells after TNF-α treatment. We also observed up-regulation of the PA28α regulator in TNF-α–treated cells, though this increase in PA28α levels was not as prominent as that observed for the proteolytic subunits (Figure 1). This could have been because of a high steady-state level of PA28α expression observed in tumor cell lines even before cytokine treatment (Figure 1).

Expression of the molecules involved in MHC class I–restricted antigen presentation is modulated by TNF-α.

Total lysates of 105 cells untreated or treated with TNF-α were subjected to Western blot analysis and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence. Specific antibodies used were directed to TAP1, TAP2, LMP2, LMP7, MECL-1, PA28α, and MHC class I heavy chain (HC). LCL, which has a phenotype of activated B cells, was used as a positive control, and T2, which has a homozygous deletion in the MHC region including both LMPs and TAPs as a negative control for catalytic subunits of the immunoproteasome and TAP1/TAP2 expression. To confirm equal protein loading in the samples, actin-specific antibodies were used for each Western blot procedure. Three to 4 independent experiments were performed for each cell line. Results of one representative experiment are shown.

Expression of the molecules involved in MHC class I–restricted antigen presentation is modulated by TNF-α.

Total lysates of 105 cells untreated or treated with TNF-α were subjected to Western blot analysis and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence. Specific antibodies used were directed to TAP1, TAP2, LMP2, LMP7, MECL-1, PA28α, and MHC class I heavy chain (HC). LCL, which has a phenotype of activated B cells, was used as a positive control, and T2, which has a homozygous deletion in the MHC region including both LMPs and TAPs as a negative control for catalytic subunits of the immunoproteasome and TAP1/TAP2 expression. To confirm equal protein loading in the samples, actin-specific antibodies were used for each Western blot procedure. Three to 4 independent experiments were performed for each cell line. Results of one representative experiment are shown.

We next investigated whether the expression of the TAP1/TAP2 heterodimer is modulated by TNF-α. Indeed, the expression of both TAP1 and TAP2 molecules was enhanced in the cytokine-treated cells (Figure 1), suggesting that translocation of the peptides from cytosol to ER may be facilitated by TNF-α treatment.

TNF-α was shown to be capable of inducing MHC class I complexes at the cell surface.39 In agreement with this, all cell lines used in this study had elevated levels of MHC class I at the cell surface after TNF-α treatment, as estimated by FACS analysis (data not shown). Moreover, we observed an induction of the heavy chain expression at the protein level (Figure 1), indicating that the total pool of MHC class I molecules is augmented by TNF-α treatment.

Taken together, our data demonstrated that TNF-α enhances the expression of key molecules involved in the MHC class I processing and presentation pathway, including subunits of the immune proteasome, TAPs, and class I heavy chain. This phenomenon was also observed in a larger panel of cell lines, including cutaneous and ocular melanomas and ovarian carcinomas (K.S. and J.L., unpublished observations, 2000).

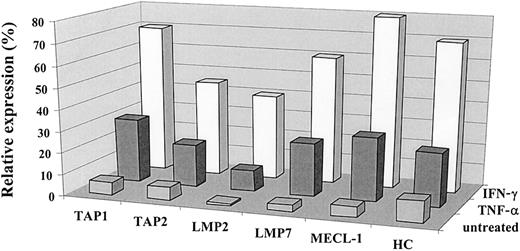

Effect of TNF-α on the antigen-processing machinery closely resembles that of IFN-γ but is independent of IFN-γ activity

IFN-γ induces the expression of MHC class I complexes, immune proteasome subunits, and TAP1/TAP2 heterodimer.23 40 The effect of TNF-α on the antigen-processing machinery observed in our experiments was similar to that reported for IFN-γ. To compare the effect exerted by these cytokines on the MHC class I processing pathway in the same cells, we treated a panel of tumor cell lines with either IFN-γ or TNF-α and subsequently monitored the expression of TAPs, immune proteasome subunits, and class I heavy chain by Western blot. As shown in Figure2, both cytokines induced changes in the expression of TAP1/TAP2, LMP2, LMP7, and MECL-1 molecules in the 0505 melanoma cell line, though the effect of IFN-γ was usually stronger. Both cytokines were capable of up-regulating MHC class I at the cell surface, as assessed by flow cytometry (data not shown), and class I heavy chain expression, as detected by Western blot analysis (Figure2). Similar data were obtained with a panel of different tumor cell lines (data not shown).

Comparative analysis of the effects of IFN-γ and TNF-α on the expression of the immunoproteasome subunits and TAPs.

The expression of TAP1, TAP2, LMP2, LMP7, MECL-1, and heavy chain proteins in the 0505 melanoma cell line was assessed by Western blot analysis and then by densitometry analysis on the specific bands. Expression of the protein of interest was analyzed by the same Western blot procedure in 3 different samples: cells propagated in complete medium (designated as untreated), in the medium containing IFN-γ (500 U/mL), or in the medium containing TNF-α (30 ng/mL). Data shown in the figure are expressed as percentage band intensity of each specific protein band in the tumor sample (untreated or treated with either of the cytokines) relative to that of the corresponding protein band in the lymphoblastoid cell line unexposed to any lymphokine (positive control), arbitrarily defined as 100% band intensity. Expression of the protein of interest in tumor cells is calculated as a percentage expression relative to that observed in a positive control and designated as relative expression. Two to 3 independent experiments were performed for each protein. Results of one experiment are shown in the figure.

Comparative analysis of the effects of IFN-γ and TNF-α on the expression of the immunoproteasome subunits and TAPs.

The expression of TAP1, TAP2, LMP2, LMP7, MECL-1, and heavy chain proteins in the 0505 melanoma cell line was assessed by Western blot analysis and then by densitometry analysis on the specific bands. Expression of the protein of interest was analyzed by the same Western blot procedure in 3 different samples: cells propagated in complete medium (designated as untreated), in the medium containing IFN-γ (500 U/mL), or in the medium containing TNF-α (30 ng/mL). Data shown in the figure are expressed as percentage band intensity of each specific protein band in the tumor sample (untreated or treated with either of the cytokines) relative to that of the corresponding protein band in the lymphoblastoid cell line unexposed to any lymphokine (positive control), arbitrarily defined as 100% band intensity. Expression of the protein of interest in tumor cells is calculated as a percentage expression relative to that observed in a positive control and designated as relative expression. Two to 3 independent experiments were performed for each protein. Results of one experiment are shown in the figure.

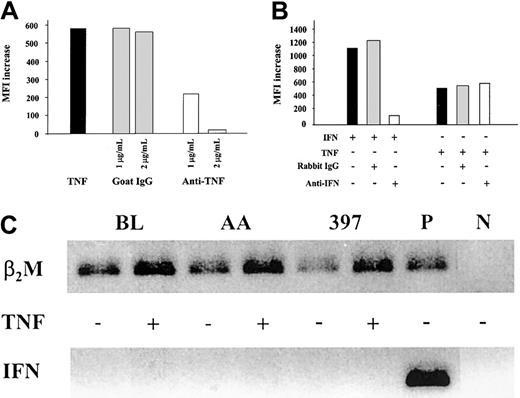

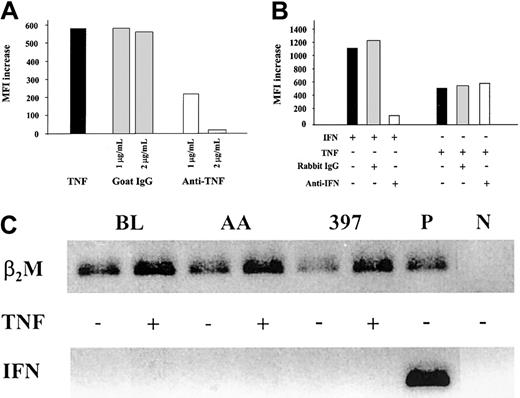

To confirm the specificity of the effects observed in the MHC class I presentation machinery on TNF-α–treatment, melanoma cells were cultured with the cytokine in the absence or presence of TNF-α–specific neutralizing antibodies. Increasing amounts of the antibodies inhibited TNF-α–induced MHC class I expression (Figure3A) and immunoproteasome induction (data not shown) in a dose-dependent manner and, when added in excess, completely abrogated the effect.

Effect of TNF-α on the MHC class I antigen-processing machinery is independent of IFN-γ activity.

(A) MHC class I up-regulation in 397 melanoma cell line treated with TNF-α is blocked by TNF-α–neutralizing antibodies. Levels of MHC class I expression in cells treated with TNF-α, alone or in the presence of either goat polyclonal TNF-α–neutralizing antibodies (designated anti-TNF) or unspecific goat IgGs, were monitored by flow cytometry. Level of MHC class I expression in each sample was compared to that in untreated cells, and the difference was expressed as MFI increase. Results of 1 of 2 representative experiments are shown. (B) MHC class I up-regulation in 397 melanoma cell line treated with TNF-α is not blocked by IFN-γ–neutralizing antibodies. Levels of MHC class I expression in cells treated with IFN-γ or TNF-α alone or in the presence of either rabbit polyclonal IFN-γ–neutralizing antibodies (designated anti-IFN) or unspecific rabbit IgGs were monitored by flow cytometry. Level of MHC class I expression in each sample was compared to that in untreated cells, and the difference was expressed as MFI increase. Results of 1 of 3 representative experiments are shown in the figure. (C) Expression of IFN-γ mRNA in BL, AA, and 397 tumor cells as assessed by RT-PCR. PCR products were separated on 1.6% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. Activated CD8+ CTL clone was used as a positive control for IFN-γ mRNA detection (P). Samples containing an aliquot of PCR-grade water were used as negative control (N). To control for RT and PCR amplification steps, β2-microglobulin mRNA was amplified from each sample.

Effect of TNF-α on the MHC class I antigen-processing machinery is independent of IFN-γ activity.

(A) MHC class I up-regulation in 397 melanoma cell line treated with TNF-α is blocked by TNF-α–neutralizing antibodies. Levels of MHC class I expression in cells treated with TNF-α, alone or in the presence of either goat polyclonal TNF-α–neutralizing antibodies (designated anti-TNF) or unspecific goat IgGs, were monitored by flow cytometry. Level of MHC class I expression in each sample was compared to that in untreated cells, and the difference was expressed as MFI increase. Results of 1 of 2 representative experiments are shown. (B) MHC class I up-regulation in 397 melanoma cell line treated with TNF-α is not blocked by IFN-γ–neutralizing antibodies. Levels of MHC class I expression in cells treated with IFN-γ or TNF-α alone or in the presence of either rabbit polyclonal IFN-γ–neutralizing antibodies (designated anti-IFN) or unspecific rabbit IgGs were monitored by flow cytometry. Level of MHC class I expression in each sample was compared to that in untreated cells, and the difference was expressed as MFI increase. Results of 1 of 3 representative experiments are shown in the figure. (C) Expression of IFN-γ mRNA in BL, AA, and 397 tumor cells as assessed by RT-PCR. PCR products were separated on 1.6% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. Activated CD8+ CTL clone was used as a positive control for IFN-γ mRNA detection (P). Samples containing an aliquot of PCR-grade water were used as negative control (N). To control for RT and PCR amplification steps, β2-microglobulin mRNA was amplified from each sample.

To exclude that the changes induced by TNF-α do not reflect an induction of endogenous production of IFN-γ, TNF-α treatment was performed in the presence of IFN-γ–specific antibodies (Figure 3B). Although the up-regulation of MHC class I expression induced by the addition of 1 U/mL IFN-γ exceeds the up-regulation observed on TNF-α–treatment, IFN-γ–neutralizing antibodies at a concentration sufficient to neutralize 5 U/mL lymphokine had no effect on the induction of MHC class I (Figure 3B) by TNF-α.

We also investigated the expression of IFN-γ mRNA in the BL, AA, and 397 cell lines (Figure 3C). RT-PCR performed on mRNA samples from either untreated or TNF-α–treated cells failed to detect IFN-γ mRNA expression in these cell lines (Figure 3C). Notably, the enhanced expression of β2m mRNA was found in TNF-α–treated samples but not in untreated controls (Figure 3C), indicating that TNF-α also up-regulates β2m expression, at least at the mRNA level. This is consistent with the observed induction of MHC class I complexes at the cell surface (data not shown) and is paralleled by the up-regulation of MHC class I heavy chain expression (Figure 1) in TNF-α–treated cells. Taken together, our results demonstrate that the effect of TNF-α on the expression of MHC class I, of TAP1/TAP2, and on the components of the immune proteasome is not accounted for by IFN-γ and appears to be due to the signaling directly mediated by TNF-α.

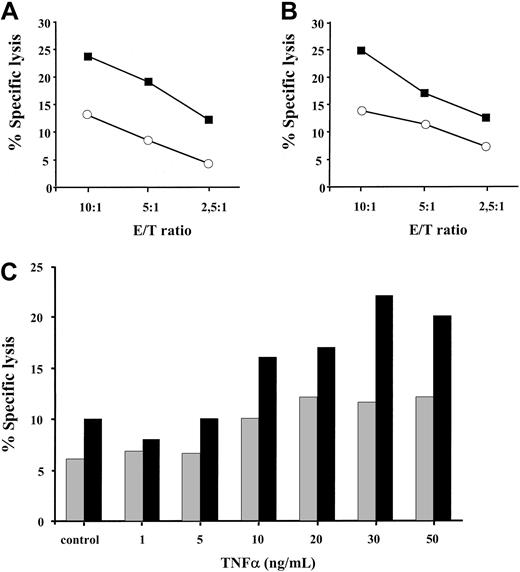

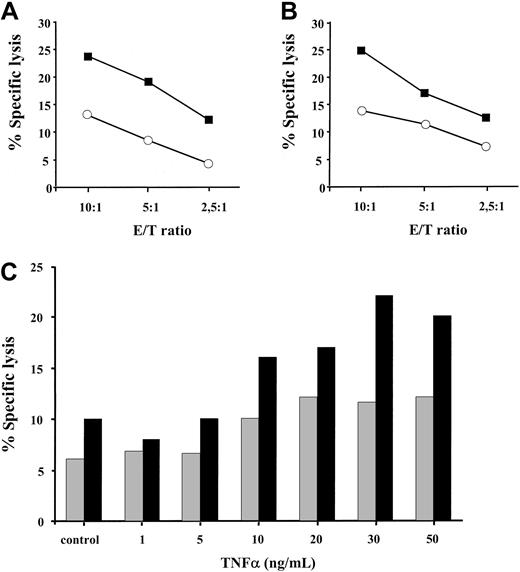

Targets exposed to TNF-α are more susceptible to lysis by MHC class I–restricted CD8+ CTL

We next sought to investigate whether the enhanced expression of the TAP1/TAP2 heterodimer and the coordinated induction of the proteolytic subunits of the immune proteosome in TNF-α–treated cells have any functional significance for MHC class I–restricted peptide presentation. Treatment of HLA A2–positive melanoma cells with 30 ng/mL TNF-α for 48 hours resulted in a 2- to 3-fold increase in specific killing by allogeneic HLA A2–specific CTLs, as determined by standard Cr-release assay (Figure 4A-B). This phenomenon was observed at different effector-to-target ratios (10:1,5:1,2,5:1) and in a larger panel of HLA A2–positive tumor cell lines (data not shown). To further substantiate this finding, we have tested the recognition of BL melanoma cells by an HLA A2–restricted CTL clone A42 specific to 27-35 peptide epitope derived from the endogenously expressed MART-1 protein (Figure 4C). BL melanoma cells were pretreated with TNF-α at different concentrations ranging from 1 ng/mL to 50 ng/mL and were subsequently tested in a cytotoxicity assay. The addition of 10 ng/mL TNF-α was required to detect an enhanced CTL recognition of the MART-1 27-35 epitope. This recognition was further augmented with an increase in cytokine concentration reaching its maximum at 30 ng/mL TNF-α (Figure 4C). Thus, TNF-α increases MHC class I–restricted allo-specific and tumor-specific CTL-mediated lysis of target cells in a dose-dependent manner.

TNF-α pretreated targets are more susceptible to lysis by MHC class I–restricted CD8+ CTLs.

HLA A2–positive DFW melanoma cell line (A) and 0505 melanoma cell line (B), either treated with 30 ng/mL TNF-α for 48 hours (▪) or left untreated (○), were tested for sensitivity to lysis by HLA A2–specific CD8+ CTLs. Results of 1 of 3 to 4 representative experiments for each cell line are shown. (C) HLA A2–positive MART-1 expressing BL melanoma cell line, either untreated (control) or exposed to different concentrations of TNF-α, was incubated with MART-1–specific HLA A2–restricted CTL clone A42 at 5:1 (░) and 10:1 (▪) effector-to-target ratios in a standard Cr release assay. Results of 1 of 2 experiments are shown.

TNF-α pretreated targets are more susceptible to lysis by MHC class I–restricted CD8+ CTLs.

HLA A2–positive DFW melanoma cell line (A) and 0505 melanoma cell line (B), either treated with 30 ng/mL TNF-α for 48 hours (▪) or left untreated (○), were tested for sensitivity to lysis by HLA A2–specific CD8+ CTLs. Results of 1 of 3 to 4 representative experiments for each cell line are shown. (C) HLA A2–positive MART-1 expressing BL melanoma cell line, either untreated (control) or exposed to different concentrations of TNF-α, was incubated with MART-1–specific HLA A2–restricted CTL clone A42 at 5:1 (░) and 10:1 (▪) effector-to-target ratios in a standard Cr release assay. Results of 1 of 2 experiments are shown.

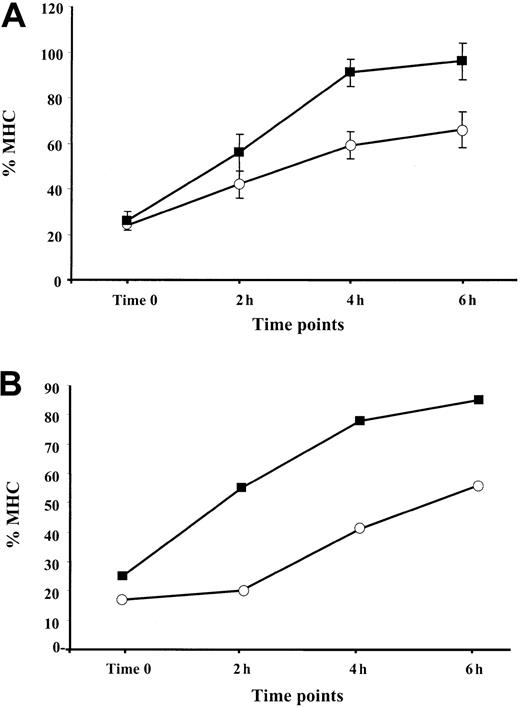

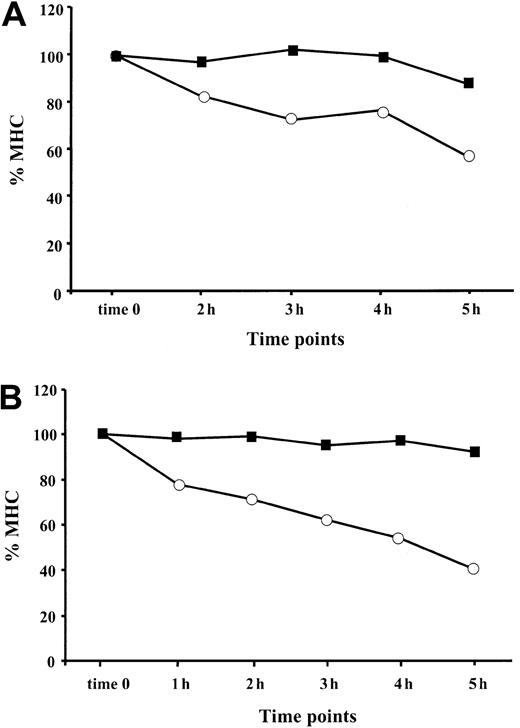

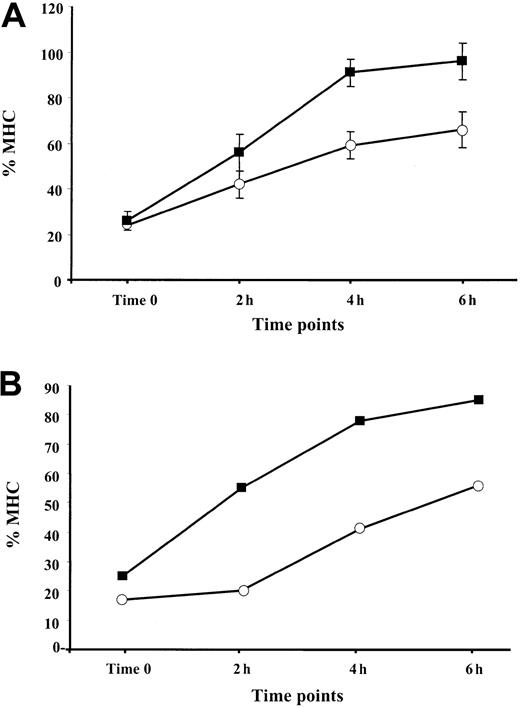

TNF-α enhances the rate of reappearance of MHC class I complexes at the cell surface

It was shown that the assembly of MHC class I–peptide complexes is a 2-step process that includes initial binding of suboptimal peptides followed by peptide optimization.41 Mechanisms of peptide optimization include the enzymatic trimming of suboptimal peptides to suitable length and peptide exchange. Optimal MHC class I–peptide complexes egress to the cell membrane, where they are displayed for CTL-dependent immune surveillance. We speculated that an induction of the immune proteasome known to produce class I epitopes or epitope precursors with proper C-termini (reviewed in Rock and Goldberg2), along with the up-regulation of TAP1/TAP2 expression by TNF-α, may increase the pool of optimal peptides in the ER, thereby increasing the rate of appearance of MHC–peptide complexes at the cell surface. To test this hypothesis, BL and 397 melanoma cells either untreated (control) or treated with 30 ng/mL TNF-α for 48 hours were shortly exposed to low pH buffer. The level of MHC class I expression measured immediately after MHC stripping (designated as time zero) was usually 15% to 25% of that expressed in the cells before stripping (initial level) (Figure 5). We found that reconstitution of the initial MHC class I level at the surface of cytokine-treated cells occurs more rapidly than in untreated samples. Approximately 90% to 100% of the initial MHC class I levels was detected after 6 hours after stripping in the TNF-α–treated 397 cell line, whereas only approximately 65% could be detected in control samples at the same time point (Figure 5A). A similar tendency was seen in experiments performed with BL cells (Figure 5B), in which augmentation of the MHC class I levels observed during 4 hours was twice as large in the cytokine-treated cells as in the untreated controls (40% vs 20%) (Figure 5B and data not shown). Our data are consistent with the hypothesis that there is an accelerated rate of reappearance of MHC class I complexes on the cell membrane in TNF-α–treated cells.

Reappearance of the MHC class I complexes at the cell surface after treatment with low pH buffer: effect of TNF-α.

Aliquots of cells cultured in standard medium with (▪) or without (○) TNF-α were treated with low pH buffer, washed, and cultured at 37°C for the indicated periods of time. For each time point, the amount of MHC class I complexes at the cell surface was calculated as percentage relative to the level of MHC class I detected before treatment with low pH buffer. (A) Reappearance of the MHC class I complexes at the cell surface of the 397 melanoma cell line. Mean ± SD of 3 experiments is shown in the figure. (B) Reappearance of the MHC class I complexes at the cell surface of the BL melanoma cell line. Results of 1 representative out of 2 performed experiments are shown.

Reappearance of the MHC class I complexes at the cell surface after treatment with low pH buffer: effect of TNF-α.

Aliquots of cells cultured in standard medium with (▪) or without (○) TNF-α were treated with low pH buffer, washed, and cultured at 37°C for the indicated periods of time. For each time point, the amount of MHC class I complexes at the cell surface was calculated as percentage relative to the level of MHC class I detected before treatment with low pH buffer. (A) Reappearance of the MHC class I complexes at the cell surface of the 397 melanoma cell line. Mean ± SD of 3 experiments is shown in the figure. (B) Reappearance of the MHC class I complexes at the cell surface of the BL melanoma cell line. Results of 1 representative out of 2 performed experiments are shown.

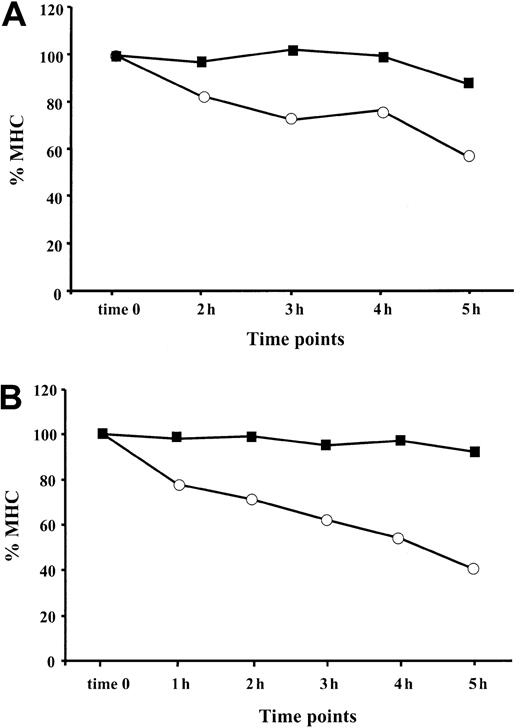

MHC class I complexes are more stable at the cell surface of cells exposed to TNF-α

After reaching the cell surface, an MHC class I–peptide complex remains stable as long as the associated peptide remains bound to the MHC groove.42-44 Empty MHC class I heterodimers are destined for rapid dissociation unless they bind exogenous peptides from the extracellular compartment.45 To decrease the possibility of peptide reassociation with empty peptide-receptive complexes, we monitored the stability of MHC I complexes under serum-free conditions. BFA, which reorganizes the structure of the ER and Golgi apparatuses,46 was used to block the egress of newly assembled MHC–peptide complexes from the ER. Both TNF-α–treated and control cells were preincubated with BFA for 1 hour and then monitored for MHC class I expression at different time points (Figure 6). We found that the stability of the MHC class I complexes at the cell surfaces of BL (Figure 6A) and 397 (Figure 6B) cell lines was significantly increased after TNF-α treatment. Only 40% to 50% of the initial MHC I complexes were detected 5 hours or more after BFA treatment in control 397 cells, whereas MHC complexes in cytokine-treated cells were stable throughout the time-frame of the experiment (Figure 6B). Approximately 90% of MHC class I remained at the cell membrane of cytokine-exposed BL cells, whereas the level of MHC class I expression in control cells was reduced by 45% after 5 hours of monitoring (Figure 6A). Taken together, our data demonstrate that surface stability of MHC class I complexes in APCs can be increased by treatment with TNF-α.

TNF-α increases stability of MHC class I complexes at the cell surface.

The presence of HLA class I at the cell surface of TNF-α–treated (▪) and control (○) cells was monitored at different time points (1 hour, 2 hours, 3 hours, 4 hours, 5 hours) after exposure to BFA. Level of MHC class I in the cell sample harvested at the end of BFA treatment is designated as time zero. MFI for each sample was calculated as the difference between the value obtained with W6/32 and isotype control antibody. Resultant intensity of fluorescence at each time point is shown as a percentage relative to the intensity of fluorescence at time zero (indicated as % MHC). (A) MHC class I stability at the cell surface of BL cell line. Results of 1 representative out of 3 performed experiments are shown. (B) MHC class I stability at the cell surface of 397 cell line. Results of 1 representative out of 4 experiments are shown.

TNF-α increases stability of MHC class I complexes at the cell surface.

The presence of HLA class I at the cell surface of TNF-α–treated (▪) and control (○) cells was monitored at different time points (1 hour, 2 hours, 3 hours, 4 hours, 5 hours) after exposure to BFA. Level of MHC class I in the cell sample harvested at the end of BFA treatment is designated as time zero. MFI for each sample was calculated as the difference between the value obtained with W6/32 and isotype control antibody. Resultant intensity of fluorescence at each time point is shown as a percentage relative to the intensity of fluorescence at time zero (indicated as % MHC). (A) MHC class I stability at the cell surface of BL cell line. Results of 1 representative out of 3 performed experiments are shown. (B) MHC class I stability at the cell surface of 397 cell line. Results of 1 representative out of 4 experiments are shown.

Discussion

Only a limited population of cells in the body maintains the MHC class I pathway in the condition necessary for the most efficient processing and presentation of antigens from the intracellular milieu. These cells, referred to as professional APCs, express immunoproteasome, high levels of TAPs, and a high density of MHC class I complexes at the cell membrane. Most somatic cells, however, do not have these characteristics and, when infected by pathogens or faced with malignant transformation, may escape CTL-mediated immune surveillance because of low immunogenicity. Hitherto, IFN-γ was the only cytokine known to induce coordinated effects on several steps of the MHC class I presentation pathway.2,23 However, human tumors can naturally acquire unresponsiveness to IFN-γ47,48 and lose the capacity to elicit protective immunity against a subsequent challenge with the wild-type tumor.49 Therefore, the availability of another agent able to substitute IFN-γ for its function in the MHC class I presentation pathway would be of particular value. Here we present data demonstrating that, as does IFN-γ, TNF-α induces coordinated changes at different steps of the MHC class I processing and presentation pathway in nonprofessional APCs. TNF-α up-regulates the expression of 3 catalytic immunoproteasome subunits—LMP2, LMP7, and MECL-1 (Figure 1)—which assemble into the immunoproteasome (as estimated by immunoprecipitation and 2-dimensional gel electrophoresis; data not shown) and induces an immunomodulatory proteasome activator, PA28α (Figure 1). It is known that the immunoproteasome does not change the rate of protein degradation compared to the constitutively acting proteasome but that it does generate an increased amount of antigenic epitopes or their precursors with proper C-termini.2,4 This leads to improved peptide uptake by TAPs and binding to class I molecules. Therefore, induction of the imunoproteasomal subunits (Figure 1) in TNF-α–treated cells should shift the repertoire of peptides presented at the cell surface. We found that TNF-α–treated cells, stripped with low pH buffer, reconstituted the surface expression of MHC class I molecules more rapidly than untreated cells (Figure 5). Recent data demonstrate that MHC class I complexes associated with nonoptimal peptide fragments are retained in the ER unless these peptides are displaced by optimal competitors that result in MHC class I transport to the cell surface.41 Therefore, the higher rate of appearance of MHC class I complexes at the cell membrane (Figure 5) could be attributed to increased production of peptides with high affinity for class I molecules. However, this may be a reflection of TAP up-regulation, also detected on TNF-α treatment (Figure 1), and enhanced peptide supply without any changes in the peptide repertoire. The latter possibility is not consistent with a slower decay of MHC class I–peptide complexes at the surfaces of TNF-α–treated cells. Because the rate of dissociation of these complexes mainly reflects the off-rate of bound peptides, the higher complex stability at the cell surface is likely to be accounted for by changes in the repertoire of class I–restricted peptides. Sequencing of peptides bound to MHC class I in TNF-α–treated and untreated cells is required to directly evaluate the extent of these changes.

Biochemical changes induced by TNF-α in the MHC class I pathway were translated into increased sensitivity of TNF-α–treated targets to the killing by allogeneic HLA A2–specific CD8+ CTLs. Allo-specific CTLs recognize MHC–peptide complexes in a peptide-dependent and a peptide-independent manner (reviewed in Sherman and Chattopadhyay50). Therefore, increased recognition by A2-specific CTLs may reflect increased HLA A2 expression at the cell surface (data not shown) and improved production and presentation of certain HLA A2–restricted peptide epitopes. It was recently demonstrated that the activity of the immuno-subunits may be segregated from the activity of the PA28 regulator because either of them was enough for enhanced presentation of the immunodominant epitope.19 Coordinated up-regulation of the proteolytic and regulatory components of the proteasome by TNF-α (Figure 1) strongly suggested that the presentation of class I–restricted peptide epitopes could be enhanced. Indeed, the presentation of the HLA A2–restricted CTL epitope derived from the endogenously expressed MART-1 antigen was enhanced in TNF-α pretreated targets (Figure 4C). It cannot be excluded that the increased sensitivity of TNF-treated targets to CTL-mediated lysis is partly accounted for by an enhanced susceptibility of cytokine-treated cells to CTL effector mechanisms, such as Fas-mediated apoptosis or exocytosis of the cytolytic granules that trigger both caspase-dependent and caspase-independent apoptotic pathways.51 52

Current knowledge of the generation of immunogenic peptide epitopes distinguishes at least 2 different proteolytic steps. Proteasomal cleavage defines the peptide C-terminus, whereas cytosolic and ER resident proteases appear to be responsible for peptide editing and for generation of its N-terminus.53 Among the growing number of peptidases involved in the trimming of the N-terminus of MHC class I–restricted peptides, leucine aminopeptidase is the only cytosolic protease known to be modulated by IFN-γ.24 It remains to be seen whether TNF-α modulates the expression of this enzyme and other peptidases involved in MHC class I processing, such as thimet oligopeptidase, which is involved in the proteolytic breakdown of certain peptide epitopes, at least in cell extracts.1 2

The effects of TNF-α on the discrete steps of the class I processing pathway are reminiscent of those of IFN-γ (Figure 2). However, we demonstrate that the effects of TNF-α observed in our experimental system are not mediated through the induction of IFN-γ, the expression of which was not detected by a sensitive RT-PCR analysis (Figure 3C). In agreement with this observation, the excess of IFN-γ–neutralizing antibodies had no effect on MHC class I (Figure3B) induction by TNF-α.

It appears likely that TNF-α–mediated effects on MHC class I processing and presentation do not involve any intermediate messengers. TNF-α elicits a variety of biologic effects through 2 distinct receptors, the TNF receptor 1 (TNF-R1; p55/p60) and TNF-R2 (p75/p80). These effects include cell growth and differentiation, immune regulation, inflammatory responses, and apoptosis (reviewed in Tracey and Cerami,54 Van Antverp et al,55 and Wallach et al56). Our data demonstrate the existence of another biologic activity exerted by TNF-α, namely its capacity to act as a coordinated multistep modulator of MHC class I pathway of antigen processing and presentation. It remains to be seen whether either TNF receptor or the cooperative action of both is necessary to provide signals leading to a concerted up-regulation of the cellular machinery of MHC class I presentation.

Our results suggest that this cytokine might be useful when modulation of the MHC class I pathway cannot be achieved by IFN-γ. These may be relevant in patients with genetic deficiencies affecting the production of IFN-γ or IFN-γ signaling pathway (reviewed in Lammas et al57 and Jouanguy et al58), in the course of tumor progression accompanied by loss of responsiveness to the lymphokine,47,48 or during infections with micro-organisms capable of interfering with IFN-γ activity.59 Our findings, in combination with new systems for targeted drug delivery,60 may pave the way for a wider use of TNF-α as a therapeutic agent.

Supported by grants from the Swedish Cancer Society, the Cancer Society of Stockholm, the King Gustav V Jubilee Fund, and the European Community.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Jelena Levitskaya, Immune and Gene Therapy Unit, Cancer Centrum Karolinska, Karolinska Hospital, KS-ringen, R8:01 17176 Stockholm, Sweden; e-mail: elena.levitskaya@mtc.ki.se.