Abstract

Polyoma BK virus (BKV) is frequently identified in the urine of bone marrow transplantation (BMT) patients with hemorrhagic cystitis (HC). However, viruria is common even in asymptomatic patients, making a direct causative role of BKV difficult to establish. This study prospectively quantified BK viruria and viremia in 50 BMT patients to define the quantitative relationship of BKV reactivation with HC. Adenovirus (ADV) was similarly quantified as a control. More than 800 patient samples were quantified for BKV VP1 gene with a real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Twenty patients (40%) developed HC, 6 with gross hematuria (HC grade 2 or higher) and 14 with microscopic hematuria (HC grade 1). When compared with asymptomatic patients, patients with HC had significantly higher peak BK viruria (6 × 1012 versus 5.7 × 107genome copies/d, P < .001) and larger total amounts of BKV excreted during BMT (4.9 × 1013 versus 7.7 × 108 genome copies, P < .001). There was no detectable increase in BK viremia. Binary logistic regression analysis showed that BK viruria was the only risk factor, with HC not related to age, conditioning regimen, type of BMT, and graft-versus-host disease. Furthermore, the levels of ADV viruria in patients with or without HC were similar and comparable with those of BK viruria in patients without HC, suggesting that the significant increase in BK viruria in HC patients was not due to background viral reactivation or damage to the urothelium. BK viruria was quantitatively related to the occurrence of HC after BMT.

Introduction

Hemorrhagic cystitis (HC) is an important cause of morbidity and occasional mortality in patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation (BMT).1 The manifestations vary from microscopic hematuria to severe bladder hemorrhage leading to clot retention and renal failure. Its incidence has varied from 7% to 68% of BMT cases.1-5 Although mild HC usually subsides with supportive treatment including blood and platelet transfusion, severe HC may require bladder irrigation, cystoscopy, and cauterization.5

Hemorrhagic cystitis has been ascribed to the toxic effects of drugs in the BMT conditioning regimen. Cyclophosphamide (Cy) is the most important one, owing to its conversion to acrolein that is highly toxic to uroepithelium.1,2,6 This can be countered by the use of 2-mercaptoethane sulfonate (MESNA),1,7 which is now included routinely in conditioning regimens containing Cy. However, despite the use of MESNA, HC still remains a clinical problem, implying that Cy is not the only cause.4 Other risks have been implicated, including the use of busulfan and pelvic irradiation during conditioning, older age at transplantation, allogeneic BMT, and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).1,5 8-11 Most of these risk factors have not been observed consistently, so that their roles in causing HC remain undefined.

The polyoma BK virus (BKV) was observed in early studies to be associated with the development of HC during BMT.12Several studies have used virologic methods to document BKV as a risk factor.1,12-14 However, subsequent studies with the highly sensitive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) showed that BKV could be detected in the urine of BMT patients with or without HC.15-18 This is owing to the fact that, after primary infection, BKV remains dormant in the uroepithelium.19During BMT, the intense immunosuppression leads to increased viral replication that results in viruria. Because over 90% of adults are seropositive for BKV, it is not unexpected that many patients may develop viruria, particularly when PCR is used to detect the virus.20 Therefore, the role of BKV in HC remains contentious. Furthermore, the lack of conclusive evidence to implicate BKV in the pathogenesis of HC has hampered the development of therapeutic measures based on inhibition of the virus.

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that although BKV could be detected nonquantitatively by PCR in most BMT patients, a quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) method might show a discriminating difference in the level of BK viruria in HC patients. We further evaluated the temporal relationship between BKV reactivation and HC, which might be important in the design of preventive strategies. Because adenovirus (ADV) infection has also been proposed to contribute to HC, mainly in pediatric BMT,21 we also quantified ADV viruria/viremia to determine if it might be a confounding factor, as well as to control for the possibility of background viral reactivation or regimen-related toxic damage to the urothelium after BMT.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patients

Fifty consecutive unselected patients undergoing BMT at Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong, were studied prospectively (Table1). None had a history of urinary tract infection, coagulopathy, or pelvic irradiation, or evidence of microscopic hematuria prior to BMT. Forty healthy individuals were recruited as controls.

Source of stem cells and conditioning regimens

There were 36 allogeneic BMTs, 13 autologous stem cell transplantations, and a single transplantation from an identical twin. In the allogeneic BMT group, 24 were from HLA-identical sibling donors, 2 from parents, and 10 from match unrelated donors (MUDs). The conditioning regimens are shown in Table 1.

Posttransplantation treatment

In allogeneic BMT (including transplantation from siblings, parents, or MUDs), prophylaxis against GVHD comprised methotrexate (15 mg/m2 on day 1, 10 mg/m2 on days 3, 6, and 11) and cyclosporine (3 mg/kg intravenously or 8 mg/kg orally days 1-50, tailed off at 6 months). Patients developing GVHD received additional immunosuppression according to the discretion of the attending physician. Two patients received BMT from one HLA antigen-mismatched parent and 10 from MUDs. They received the same GVHD prophylaxis as other allogeneic BMT recipients. Patients receiving autologous BMT or allogeneic BMT from HLA-identical siblings were given acyclovir (5 mg/kg every 8 hours) for prophylaxis against herpes simplex infection, from the commencement of conditioning to day 30 after BMT. In patients undergoing allogeneic BMT from parents and MUDs, high-dose acyclovir (10 mg/kg every 8 hours) was given from conditioning to marrow engraftment, followed by ganciclovir (5 mg/kg) 3 times a week until day 120, for prophylaxis against cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Patients undergoing BMT from HLA-identical siblings did not receive prophylactic ganciclovir. Pre-emptive ganciclovir therapy (5 mg/kg per day) was administered to patients with 2 consecutive PCR tests positive for CMV, and continued until PCR turned negative on 2 occasions.

Prophylaxis against HC

For patients receiving conditioning regimens containing Cy, prophylaxis against HC included forced diuresis with intravenous fluid at 3 L/m2 per day from 4 hours before to 24 hours after the Cy therapy. MESNA was given at a dose of 25 mg/kg prior to Cy, and 75 mg/kg thereafter as a continuous infusion over 20 hours until the last dose of Cy.

Diagnosis and treatment of HC

Urinalysis by dipstix (Multiple Reagent Strips, Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany), with a sensitivity of 5 to 20 red blood cells/μL, was performed daily throughout the hospital stay. HC was diagnosed according to the criteria proposed by Bedi and coworkers4 (grade 1, microscopic hematuria on more than 2 consecutive days; grade 2, macroscopic hematuria; grade 3, macroscopic hematuria with clots; grade 4, macroscopic hematuria with clots and impaired renal function secondary to urinary tract obstruction). The presence of dysuria or lower abdominal pain (or both) was an additional criterion applicable to all grades of HC. The treatment of grade 1 and 2 HC was conservative, with increased fluid intake and frequent voiding. Grades 3 and 4 HC were treated with continuous bladder irrigation. Therapy for refractory HC included flexible cystoscopy and evacuation of blood clots, intravesical alum instillation, electrical cauterization, and intravesical formalin, singly or in combination.

Diagnostic specimens

For BMT patients, 24-hour urine specimens and 1 mL plasma were collected a day before the commencement of conditioning, on the day of marrow infusion (day 0), and weekly thereafter until discharge from the hospital. Urinary collection might be temporarily suspended during bladder irrigation in cases of severe HC. The 24-hour urine sample was collected for the quantification of viruria to obviate potential problems related to variation of viruria during the day. When HC developed, specimen collection was repeated every 3 days. The volume of urine was recorded and 50 mL was aliquoted and centrifuged at 3200 rpm for 30 minutes. The urinary sediment so obtained was washed with saline and resuspended in 200 μL water. DNA was extracted by the QIAamp DNA Blood Minikit (Qiagen, Basel, Switzerland) and eluted with 200 μL buffer. DNA was also extracted from each of 200 μL free urine and plasma collected at the similar time points with the same protocol. For the healthy controls, only a spot 50-mL urine sample was collected and processed as for BMT patients. Plasma (but not whole blood) was used for quantification of viremia to avoid interference due to the presence of BKV in the nucleated cells.

Conventional PCR for BKV

Conventional PCR for the BKV VP1 gene (GenBank accession number V01109) was performed the forward primer VPf (5′-AGT GGA TGG GCA GCC TAT GTA-3′) and the reverse primer VPr (5′-TCA TAT CTG GGT CCC CTG GA-3′), which gave a 95-base pair (bp) product.

Q-PCR

Quantitative PCR was performed by a real-time PCR assay, a technique that allows simple and rapid quantification of a target sequence to be made during the exponential phase of the PCR, using the ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detector (PE Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Briefly, PCR primers for the BKV VP1 gene (VPfand VPr), and the TaqMan BKV probe (5′-AGG TAG AAG AGG TTA GGG TGT TTG ATG GCA CAG-3′) dual-labeled at the 5′ end with 6-carboxyfluorsecein (FAM) and the 3′ end with 6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA), were designed by the Primer Express software (PE Biosystems). Q-PCR amplification reactions were set up in a reaction volume of 50 μL using the TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (PE Biosystems), containing 10 μL purified DNA, 200 and 400 nM of VPf and VPr, and 50 nM TaqMan probe. Thermal cycling was initiated with a 2-minute incubation at 50°C, followed by a first denaturation step of 10 minutes at 95°C, and then 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds (denaturation) and 60°C for 1 minute (reannealing and extension). Real-time PCR amplification data were collected continuously and analyzed with the Sequence Detection System (PE Biosystems). Quantification of ADV viruria was performed similarly. A 72-bp sequence in the ADV hexon gene with homology shared by serotypes 11, 34, and 35 (GenBank accession number AB018424) was amplified by the primers HEXf (5′-ACT ACA TGA ACG GGC GGG T-3′) and HEXr (5′-GAG ACC ACC TGG CAC CAA TG-3′) and detected by the TaqMan ADV probe 5′-FAM (TGC CGC CAT CTC TAG TAG ACA CCT ATG TGA TAMRA-3′). The conditions of Q-PCR were the same as those of BKV.

Cycle thresholds (CT) at which a significant increase in fluorescence signal was first detected were set at a minimum of 10 SDs above the mean baseline fluorescence, calculated from cycles 1 to 15. The copy number of target sequences in the tested samples was inversely proportional to and hence can be deduced from the CT.21

Quantification of BKV and ADV

Standard curves for the quantification of BKV and ADV were constructed by plotting the CTs against the logarithm of the starting amount of serial dilutions (0.5 fg to 5 pg) of the plasmid standards pB-VP1 (containing the BKV VP1 gene target sequence, Figure 1) and pB-Hex (containing the ADV hexon gene target sequence). For the cloning of pB-VP1, a segment of the VP1 gene was amplified from a BK viral suspension by PCR with a pair of primers (forward primer: 5′-CGC AAT TCTAGA GGA ACA CAA CAG TGG AGA GGC-3′; reverse primer: 5′-CGC AAT TCTAGA AGG TCA GAC CCC CAT AGT CAA G-3′) containing 5′ XbaI overhanging sites (underlined), which flanked the portion of the VP1 gene detected by Q-PCR. The 417-bp PCR product was cloned into theXbaI site of pBluescript (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) to give the plasmid pB-VP1. The sequence of the cloned BK VP1fragment was confirmed by DNA sequencing in both orientations on an automated DNA sequencer (ABI Prism 377, PE Biosystems). The ADV plasmid standard was prepared similarly. A 226-bp segment of the hexon gene containing the Q-PCR target sequence was amplified from ADV by PCR with a pair of primers containing XbaI overhanging sites (underlined) (forward primer: 5′-A CGT TCTAGATCG TAC AAA TAC ACC CCG TCC-3′; reverse primer: 5′-C AGTTCTAGA CGT TAC CCA GAA GCA TGG ATC-3′), cloned into pBluescript (pB-Hex), and sequenced for confirmation of nucleotide sequence.

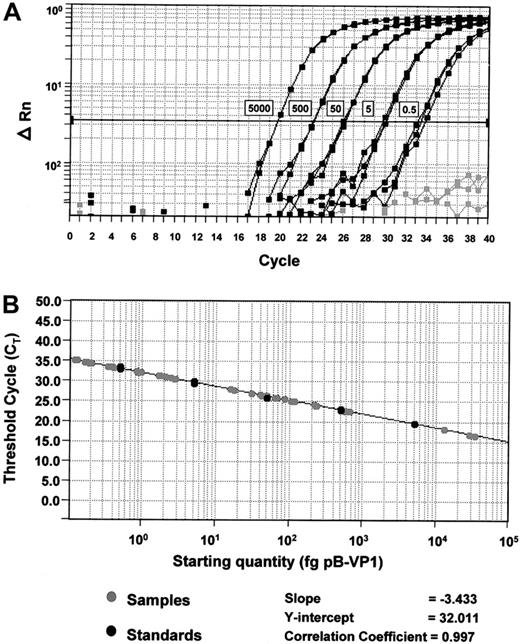

Standard curves for quantification of BKV and ADV.

(A) Amplification plots of pB-VP1 for the construction of a standard curve. Amplification plot for reactions with known starting amounts of pB-VP1 (0.5-5000 fg plasmid DNA, denoted by boxes next to the corresponding curves). Gray curves denote no template control reactions. Cycle number is plotted against change in normalized reporter signal (ΔRn). For each reaction, the fluorescence signal of the reporter dye (FAM) is divided by the fluorescence signal of the passive reference dye (ROX), to obtain a ratio defined as the normalized reporter signal (Rn). (B) Plot of standard curve of starting pB-VP1 amount against CT. Black circles represent pB-VP1 standards as demonstrated in panel A. Gray circles represent patient samples. A standard curve is constructed for every assay.

Standard curves for quantification of BKV and ADV.

(A) Amplification plots of pB-VP1 for the construction of a standard curve. Amplification plot for reactions with known starting amounts of pB-VP1 (0.5-5000 fg plasmid DNA, denoted by boxes next to the corresponding curves). Gray curves denote no template control reactions. Cycle number is plotted against change in normalized reporter signal (ΔRn). For each reaction, the fluorescence signal of the reporter dye (FAM) is divided by the fluorescence signal of the passive reference dye (ROX), to obtain a ratio defined as the normalized reporter signal (Rn). (B) Plot of standard curve of starting pB-VP1 amount against CT. Black circles represent pB-VP1 standards as demonstrated in panel A. Gray circles represent patient samples. A standard curve is constructed for every assay.

Patient samples were tested in triplicate, their respective CTs were determined, and the initial starting sequence amount calculated from the standard curve (Figure 1). The calculations for daily viruria for BKV and ADV were identical. To convert to viral genome equivalent copies, the following formula was used:Np, where x is the amount in picograms, 6.023 × 1023 is the number of copies in 1 mole of plasmid, and 660 Np is the molar weight of the plasmid (660 is the average molecular weight of a nucleotide pair, and Np is the number of nucleotide pairs in the plasmid standard, being 3 367 for pB-VP1, and 3 176 for pB-Hex). To calculate the daily viral excretion, results from 10 μL extracted DNA obtained by Q-PCR were multiplied by the following correction factors: 20 × 24-hour urine volume (mL)/50 for urinary sediment, and 20 × 5 × 24-hour urine volume (mL) for free urine. To calculate the total viral excretion during the BMT period (both sediments and free urine), the daily viral excretion (in genome copies) was integrated over time during BMT (ie, area under the curve in a plot of viral excretion versus time) using computer software (PRISM, Graphpad Software, San Diego, CA).

PCR precautions

All precautions preventing contamination were rigorously adhered to. DNA extraction, cloning of pB-VP1/pB-Hex, and Q-PCR were performed in 3 different laboratories. All samples were handled with positive displacement pipettes with aerosol-resistant tips. Negative blanks included in each PCR did not give positive results.

Quality assurance of Q-PCR

To control for plate-to-plate variation in PCR efficiencies, so that all results were comparable, a standard curve was constructed in each Q-PCR experiment with serial dilutions of the same stock solution of pB-VP1/pB-Hex, which was prepared at the start of the project and frozen at −20°C in small aliquots for single use only.

Statistical analysis

Comparison between groups of data were performed with the Mann-Whitney test or the Kruskal-Wallis test. To define the relationship between BK viruria and HC, the following measurements of BK viruria were evaluated: peak = viruria at the day of peaking of BK viruria; total = total viruria during BMT; viruria prior to HC = total viruria prior to the onset of HC in HC patients, and total viruria during BMT in non-HC patients; mean daily viruria prior to HC: total viruria/number of samples, collected prior to HC in HC patients, and total viruria/number of samples collected during BMT in non-HC patients. The contribution of potential risk factors to the occurrence of HC was evaluated by binary logistic regression (SPSS, Chicago, IL). The occurrence of HC was the dependent variable and the following factors were entered as covariates: age of the patients, the source of stem cells (autologous versus siblings versus matched unrelated donors), the conditioning regimens (non-Cy/total body irradiation [TBI] versus Cy versus Cy + TBI), the presence of GVHD (grade ≥ 2) prior to HC, the lowest platelet count and the highest serum creatinine concentration during HC (HC group) or BMT (non-HC group), the peak and total BK viruria, and the total ADV in urinary sediments and free urine. P values of less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients and clinical course

The clinical characteristics of the patients were shown in Tables1 and 2. Twenty patients developed HC (Tables 3 and4). Two patterns of HC can be defined. In patients 1 through 6, HC presented as gross hematuria (≥ grade 2) and occurred after hematopoietic reconstitution, with median onset at day 37 (range, 29-72). A combination of medical and surgical treatment in these patients did not result in immediate cessation of bleeding, which lasted a median of 18 (range, 8-110) days. On the other hand, in patients 7 through 20, HC presented with only microscopic hematuria (grade 1), with median onset at day 4 (range, 1-25). The onset of high-grade HC (≥ grade 2) was significantly later than that of grade 1 HC (day 37 versus day 4, P < .01).

PCR

Conventional PCR for BKV was positive in the urinary sediments of all 50 patients at 2 or more time points during the BMT period. However, it was not demonstrable in any of the plasma specimens tested. As leukopenia developed during BMT, making the number of white cells in the urine small, BKV detection in urinary sediments was unlikely to be explained by the presence of blood in the urine. In the normal controls, 16 of 40 (40%) showed weakly positive PCR results.

Q-PCR of BKV

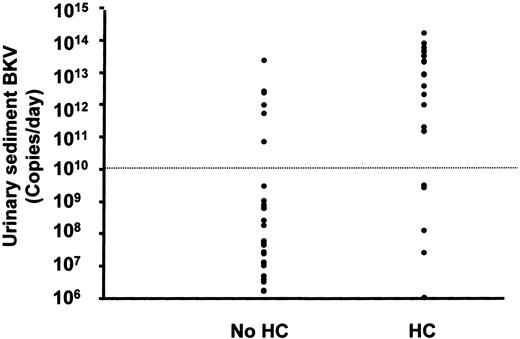

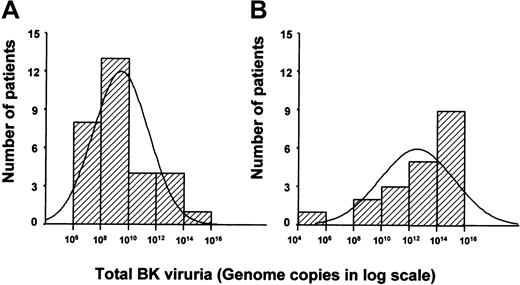

The BK viruria was quantifiable serially in all 50 patients (median: 7 time point, about 800 samples analyzed). Quantification of BKV in free urine and urinary sediment showed results comparable in both magnitude and timing (Table 2). For simplicity of data presentation, only results of urinary sediments will subsequently be shown. A detectable rise in viruria (> 10 times the baseline) occurred in 47 patients. Three patients had no significant increase in viruria. The time from BMT to peak viruria varied from 2 to 57 days (median, 15 days). There was no significant difference between the timing of peak viruria in patients with or without HC (day 21 versus day 14, P = .2). However, the peak viruria in patients with HC was significantly higher than those without HC (median peak value 6 × 1012 versus 5.7 × 107 genome copies, P < .001) (Figure2). Furthermore, the total amount of virus excreted during the BMT period was also significantly higher in patients with HC as compared to those without (4.9 × 1013 versus 7.7 × 10,8P < .001; Figure 3). This difference was not related to a difference in the total number of samples collected, because the median numbers of urine samples collected for HC and non-HC patients were 9 and 7, respectively, and the median durations of hospitalization were 40 and 41 days (P > .05 for both parameters, Mann-Whitney test). Finally, both the total and the mean daily viruria prior to the onset of HC were significantly higher in HC patients as compared with non-HC patients (8.6 × 1012 versus 7.7 × 10,8P < .001, and 5.3 × 1011 versus 2.3 × 10,7P < .001). In the control subjects where BKV could be detected by conventional PCR, Q-PCR of spot urine samples showed a median genome copy of 5.3 × 103/mL (range, 3.1 × 101-1.5 × 106 copies/mL). Assuming that the average urine output in normal subjects was in the order of 103 mL/d, the controls had comparable levels of BK viruria as patients without HC.

Peak BKV excretion per day in patients with and without HC, showing a significant difference in viral excretion between the 2 groups.

An arbitrary cutoff at 1010 genome copies/d gives the best predictive value for the occurrence of HC. This also identifies all patients with HC grade 2 or higher.

Peak BKV excretion per day in patients with and without HC, showing a significant difference in viral excretion between the 2 groups.

An arbitrary cutoff at 1010 genome copies/d gives the best predictive value for the occurrence of HC. This also identifies all patients with HC grade 2 or higher.

Total BKV viral excretion during the entire BMT period plotted against the number of patients.

This showed a significant difference between the median total viral excretion in patients without HC (in the range of 108-1010, panel A) as compared with patients with HC (in the range of 1012-1014, panel B).

Total BKV viral excretion during the entire BMT period plotted against the number of patients.

This showed a significant difference between the median total viral excretion in patients without HC (in the range of 108-1010, panel A) as compared with patients with HC (in the range of 1012-1014, panel B).

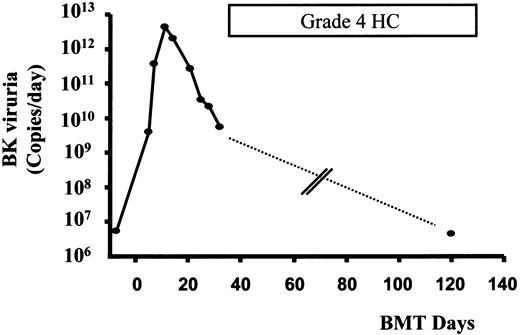

Parallel with the 2 clinical types of HC, 2 patterns of viruria were observed. In patients 1 through 6 with HC of grade 2 or higher, peaking of viruria preceded the onset of HC (Figure4). On the other hand, in patients 7 through 20 with grade 1 HC, peaking of viruria either coincided or occurred later than the onset of HC in most of the patients.

Time course of HC and BK viruria in patient 1.

Peaking of BK viruria preceded the onset of HC by about 2 weeks. Quantification of BK viruria during severe HC on day 120 showed a low level of viruria. No urinary specimen was available for quantification from 32 to 120 days (dashed line) (see text).

Time course of HC and BK viruria in patient 1.

Peaking of BK viruria preceded the onset of HC by about 2 weeks. Quantification of BK viruria during severe HC on day 120 showed a low level of viruria. No urinary specimen was available for quantification from 32 to 120 days (dashed line) (see text).

Quantitative PCR was also performed in 144 plasma specimens from 46 patients. Although BKV was not detected by conventional PCR in any of the cases, it was quantifiable in 42 cases (Table 2). There was no detectable increase in BK viremia in any of the patients during the course of BMT, including those samples that were taken before, during, or after the onset of HC. There was also no significant difference in the level of BK viremia in patients with or without HC.

HC and BK viruria

Although as a group patients with HC have significantly higher levels of viral excretion as compared to those without, there were some overlaps. As shown in Figure 2, taking more than 1010 BKV copies/d as a cutoff, of 21 patients considered to have significant viruria, 15 developed HC (grade 1-4). In the remaining 29 patients with viruria less than 1010 copies/d, only 5 of them had grade 1 HC. Therefore, BKV excretion of more than 1010 copies/d occurred in all the cases with severe HC (grade > 2) and 9 of 14 patients with mild HC (grade 1). On the other hand, 6 of 30 patients without HC also had significant viral shedding (Table5). When the amount of viruria was analyzed according to the severity of HC, patients with HC of grade 2 or higher had levels of BK viruria comparable to patients with HC of grade 1 (peak viruria 1.4 × 1013/d versus 1.1 × 1012; total viruria: 2.5 × 1014versus 3.9 × 1012, respectively, P > .05, Mann-Whitney test).

Q-PCR of ADV

The ADV viruria was quantifiable in all patients. A detectable rise in viruria in either urinary sediment or free urine (> 10 times the baseline level) occurred in 28 patients during the course of BMT. In the remaining 22 patients, ADV viruria remained at a steady level throughout the BMT (the highest level during BMT was taken as the peak). There was no association of the occurrence of HC with a rise in viruria (15 patients in HC group had an increase in ADV viruria versus 13 patients in non-HC group), or with the median time of peak viruria (in both HC and non-HC group, ADV viruria in the urinary sediments peaked at 21 days after BMT, and in free urine at 16 and 14 days, respectively). Furthermore, the magnitude of ADV viruria was also comparable in patients with or without HC (Table 2). This was shown both in the free urine and sediment, although for reasons not defined in this study, the levels of ADV in the free urine consistently exceeded those of the sediment. Interestingly, the median level of ADV viruria in the free urine in patients with or without HC were comparable with that of BKV in patients without HC (2.2 × 107 versus 7.5 × 107 versus 2.2 × 108, P = not significant); but all 3 were 4 to 5 logs lower that the median level of BKV in patients with HC (2 × 1012). Finally, the level of ADV viremia at the time of peak viruria was similar in patients with or without HC, which was comparable with that of BK viremia in patients without HC (Table 2).

HC, viruria, and clinicopathologic parameters

Among the various factors entered into the time-dependent binary logistic regression, only the quantity of peak daily BK viruria and the lowest platelet count during HC (HC group) or BMT (non-HC group) had a significant association with the occurrence of HC. When these parameters were compared between patients with mild (grade 1) or severe (≥ grade 2) HC, patients with severe HC had significantly higher platelet count compared with those with mild HC (Table 4).

Discussion

In this study, we have addressed several important issues concerning BK viruria and HC during BMT. We demonstrated that using the PCR to test for BK viral sequence, viruria occurred in all BMT patients, but only 40% of them developed HC. This phenomenon has been shown previously,15-17 making the original observations of the association between BK viruria and HC controversial. To resolve this problem, our study indicated that although there was baseline viruria, Q-PCR showed that HC patients had significantly higher viral excretion. The peak viruria and total viral excretion in HC patients were approximately 105 times higher than non-HC patients, respectively. Because it is unknown whether variations of viral excretion might occur during the day, we have chosen to examine 24-hour urine to obviate possible problems associated with the study of spot urine samples. However, a previous study examining spot urine with a competitive PCR technique22 showed that patients with or without HC excreted 106 to 107 and 2 × 104 to 8.9 × 105 BKV copies/mL, respectively. Although the technique was different, the magnitudes of BK viruria in that study were similar to those in our study (assuming that the daily urine output was in the order of 103 mL). Therefore, our results showed that BK viruria was quantitatively related to the occurrence of HC.

Several confounding factors might influence the significance of the increase in BK viruria. First, this might simply be a reflection of injury to the urothelium due to the conditioning regimen. However, BK viruria in patients without HC was similar in magnitude to normal controls, arguing against a significant regimen-related damage to the bladder epithelium. Furthermore, quantification of ADV as a control showed that patients with or without HC excreted similar levels of viruria, which was interestingly comparable with BK viruria in non-HC patients and normal control subjects. These results showed that the increase of BK viruria in HC patients was not due to urothelial toxicity and background viral reactivation. Second, BKV has been shown to cause nephropathy.23 In this study, some of the patients developed BK viremia, albeit at low levels detectable only by Q-PCR, which might be a more sensitive test than conventional PCR. However, the renal functions of patients with or without viruria and HC were similar, so that nephritis had not contributed significantly to the clinical manifestations. Third, patients with or without HC had similar clinical features and complications from BMT leading to a comparable hospital stay duration, making it also unlikely that these were confounding factors. Therefore, our findings suggest that BKV has actually played an important role in the pathogenesis in HC after BMT.

In the present study, we have noted 2 clinical types of HC. Early onset HC occurred before hematopoietic reconstitution and was of low grade. However, late onset HC occurred after marrow engraftment and was of high grade. Furthermore, although BK viruria was quantitatively related to HC, the levels did not correlate well with the clinical severity (of the patients with significant viruria shown in Table 2, 9 patients had grade 1 HC, and 6 patients did not have hematuria), suggesting that BK viral damage of the urothelium would not be the only factor in the development of HC. To explain these observations, we tentatively propose a model to explain how BKV might have led to different patterns of HC. After BMT, the intense immunosuppression results in an increase in viral replication. When viral reactivation occurs at a low level, this is clinically silent and the patients remain asymptomatic. When viral replication exceeds a certain level (approximately 1010 copies/d as defined in the urinary sediment), the BKV, a cytopathic virus, causes significant uroepithelial cell lysis that results in hematuria. In some patients, the accumulation of BKV leads to an immunologic response, which targets uroepithelial cells for destruction by regenerating immunocompetent cells after engraftment. Because this phase involves an inflammatory response, the cellular destruction is more intense than mere viral cytopathic effects, thereby resulting in more severe HC.

Several lines of evidence support this model. Immunosuppression leads to increased BKV replication, both in renal allograft and BMT recipients.24,25 Furthermore, BKV infection may also elicit an inflammatory response due to the expression of viral products.20,26 This inflammatory response is absent in HC of early onset when engraftment has not yet happened. However, in patients with HC occurring after engraftment, regenerating immunocompetent cells may cause increased tissue damage, which has been suggested to be a possible pathogenetic mechanism in some cases of CMV-associated interstitial pneumonitis after BMT.27 28 In further support of this model, we have looked for the presence of BKV in biopsies of bladder wall in patients with high-grade HC. Immunohistochemical staining for the BKV large T antigen was negative (Dr H. Hirsch, personal communications, August 2000), implying that at the time of severe HC, BKV-mediated cell lysis may not be a main component.

However, some observations in our study remain unexplained by this model, which is tentative and intended to provide a framework to test further hypothesis, and is therefore not necessarily the only possible mechanism. First, the lack of correlation between BK viruria and HC severity implied that other coexisting factors might be needed for the development of HC. We therefore examined whether risks potentially associated with HC, including the use of Cy and irradiation, age, GVHD, platelet count, and adenoviruria,1,5,8-11,29,30 might be contributory. In the binary logistic regression analysis, except BK viruria, none of these factors was an independent risk. Interestingly, patients with severe HC actually had a higher platelet count during HC. This was not unexpected, because severe HC had a late onset after donor marrow engraftment and hence a higher platelet count at that time. Second, this study has not addressed the factors leading to reactivation of BKV significant enough to cause HC in some patients. It did not appear to be related simply to the level of immunocompromise, because the type of BMT (autologous versus allogeneic), which determined the level of immunosuppression, did not have a significant impact on HC. Third, although plasma BKV was quantifiable, there was no significant increase in any of the patients during the clinical course, implying that plasma BKV PCR might not be a useful test in HC. This is different from renal allografting, where BKV PCR is useful in predicting the occurrence of viral nephropathy.23 Finally, there was a highly variable interval (range, 1-58 days) from peak viruria to the onset of severe HC, and whether this could be fully explainable by our proposed model or was due to other confounding factors not examined in this study remains unclear. However, the demonstration in this study of a highly significant increase in BK viruria indicates a role in the pathogenesis of HC. Hence, the above observations should probably not be seen to negate the importance of BKV in HC, but rather to provide grounds for further research.

The findings of this study are of potential therapeutic implications. Presently, there is no satisfactory treatment of HC of grade 2 or higher. Medical treatment with conjugated estrogens and urosurgical interventions have variable successes, so that HC continues to cause prolonged morbidity in BMT patients. We have shown that significant viruria invariably occurred in patients who would ultimately develop HC, particularly in those severely affected, who would benefit most from early or preventive treatment. However, the positive predictive value of BK viruria for severe HC is still low in our study, owing to the fact that some patients with significant BK viruria might not develop HC. The definition of possible coexisting factors that may act with BK viruria to give rise to HC may improve the predictive value of this test, possibly by studying a larger number of patients with severe HC that occurs after engraftment. Our observation that a BKV surge often precedes severe HC implies that prophylactic suppression of BKV replication may be of preventive benefit. In this study, all patients have received acyclovir prophylaxis, and most have received ganciclovir. These agents did not appear to have any impact on BK viruria. However, newer nucleoside analogues have been found to show in vivo and in vitro activities against polyoma viruses.31Furthermore, bacterial DNA gyrase inhibitors have also been shown to suppress BKV replication and cytopathic effects in vitro.32 These agents need to be evaluated prospectively to see if they are of use in suppressing BKV replication and therefore the occurrence of HC.

In conclusion, the results of this study support that BKV plays a role in the pathogenesis of HC after BMT, based on its temporal and quantitative association with this disorder. Preventive measures based on inhibition of BK viral replication may therefore be of clinical benefit.

The authors thank Dr Hans Hirsch, University Hospitals Basel, Switzerland, for BKV large T-antigen staining on bladder biopsies, and Dr M Ng for advice on statistical analysis.

Supported by a grant from the Kadoorie Charitable Foundation.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Yok L. Kwong, University Department of Medicine, Professorial Block, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong; e-mail: ylkwong@hkucc.hku.hk.