Heme, a ubiquitous iron-containing compound, is present in large amounts in many cells and is inherently dangerous, particularly when it escapes from intracellular sites. The release of heme from damaged cells and tissues is supposed to be higher in diseases such as malaria and hemolytic anemia or in trauma and hemorrhage. We investigated here the role of free ferriprotoporphyrin IX (hemin) as a proinflammatory molecule, with particular attention to its ability to activate neutrophil responses. Injecting hemin into the rat pleural cavity resulted in a dose-dependent migration of neutrophils, indicating that hemin is able to promote the recruitment of these cells in vivo. In vitro, hemin induced human neutrophil chemotaxis and cytoskeleton reorganization, as revealed by the increase of neutrophil actin polymerization. Exposure of human neutrophils to 3 μM hemin activated the expression of the chemokine interleukin-8, as demonstrated by quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction, indicating a putative molecular mechanism by which hemin induces chemotaxis in vivo. Brief incubation of human neutrophils with micromolar concentrations of hemin (1-20 μM) triggered the oxidative burst, and the production of reactive oxygen species was directly proportional to the concentration of hemin added to the cells. Finally, we observed that human neutrophil protein kinase C was activated by hemin in vitro, with a K1/2 of 5 μM. Taken together, these results suggest a role for hemin as a proinflammatory agent able to induce polymorphonuclear neutrophil activation in situations of clinical relevance, such as hemolysis or hemoglobinemia.

Introduction

Heme released from hemeproteins has been shown to promote the formation of oxygen radicals, playing a role as a catalyst in the oxidation of lipids, proteins, and DNA.1-3In addition, free heme can promptly bind to and oxidize low-density lipoprotein, acting as a biologically relevant lipoprotein oxidant.4 Hemoglobin (probably because of the release of free heme and heme iron) may contribute to the acute renal failure often seen after episodes of intravascular hemolysis.5,6 In fact, it has been proposed that heme could be considered one causative agent in organ failure after ischemia-reperfusion because heme-oxygenase is induced in heart and kidney.7

In normal conditions, diverse species produce avid heme-binding plasma proteins, such as hemopexin, that efficiently remove most of the heme produced intravascularly,8 thus preventing nonspecific cellular heme uptake and heme-catalyzed oxidation reactions. However, pathologic situations of increased hemolysis can lead to very high levels of free heme, as in malaria,9 sickle cell disease,10 HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver levels, and low platelet count) syndrome,11 or regions with turbulent blood flow.12 Very little work has been done to assess the consequences of the interaction of free heme with intact cells. It has been demonstrated that free heme is promptly incorporated into endothelial cells in vitro and that this association potentiates the oxidative damage induced by chemical agents.13 It is interesting to note that patients suffering from sickle cell disease often exhibit a low-grade chronic inflammation. This state correlates with the enhanced expression of adhesion molecules on activated endothelial cells, leukocytes, and reticulocytes,14-16 but the specific agent that triggers this process remains unknown.

Leukocyte migration into tissues is the hallmark of all types of inflammatory responses. Polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) are blood-borne inflammatory cells with oxidative and proteolytic potential that are usually the first cells involved in pathogen recognition, playing an essential role in the host defense against invading microorganisms. The inflammatory process can be amplified by the neutrophils themselves through the production of arachidonic acid–derived bioactive lipids such as leucotriene B4 (LTB4), cytokines (ie, interferon-γ, interleukin-1 [IL-1], tumor necrosis factor–α), or chemokines (IL-8, growth-related oncogene-α [GROα]). On exposure to the proper stimulus, PMNs also release a variety of reactive oxygen species (ROS), including superoxide anion (O2.−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydroxyl radical (.OH), and hypochlorous acid (HOCl).17 The generation of O2.− by PMNs occurs during phagocytosis or upon stimulation by soluble agonists, such as phorbol ester, chemotactic peptides, and calcium ionophore.18 Binding of several agonists to their specific receptors has been shown to trigger a signal-transduction cascade that ultimately activates reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase. Several pieces of evidence point to protein kinase C (PKC) activation as an essential step for the initial activation of NADPH oxidase and, consequently, to the production of ROS.19-21

In the present paper, we provide evidence that heme can modulate several neutrophil-related responses either by a PKC-dependent pathway (such as migration, actin cytoskeleton reorganization, and ROS production) or by a PKC-independent mechanism (IL-8 expression). The data reported here indicate that heme can act as a physiologically relevant proinflammatory signaling molecule that may be associated with the development of inflammation in hemolytic diseases.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats (150-180 g) supplied by the breeding facilities of Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) were housed in temperature-controlled rooms and given water and food ad libitum until use. The animals were treated in accordance with published regulations and guidelines for animal experiments.

Hemin

Hemin (cell culture grade; Sigma, St Louis, MO) stock solutions (5 mM) were made in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; culture grade) and diluted in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) immediately before use. The final concentration of DMSO was kept lower than 0.01% for all assays.

Acute pleurisy in rats

Acute pleurisy was induced as described earlier.22Briefly, hemin was injected into the thoracic cavity of rats (30-300 nmol/cavity) in a volume of 100 μL. The animals were killed 4 hours after injection under ether anesthesia, and their thoracic cavities were opened and rinsed with 3 mL PBS containing heparin (10 IU/mL). Total leukocytes in the pleural fluid were determined on Neubauer chambers after dilution in Turk solution (Laborclin, São Paulo, Brazil). Differential counting of leukocytes was carried out on May-Grünwald-Giemsa–stained slides.

Human neutrophil isolation

Neutrophils were isolated from ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (0.5%)-treated peripheral venous blood of healthy human volunteers using a 4-step discontinuous Percoll (Sigma) gradient.23 Erythrocytes were removed by hypotonic lysis, and PMNs were resuspended in RPMI-1640 medium (Sigma) or Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM). Neutrophil purity and viability were always higher than 99% and 96%, respectively. The trypan blue assay was used to evaluate hemin toxicity, and no cellular lysis was observed in the presence of up to 50 μM hemin for 2 hours (data not shown).

Neutrophil chemotaxis

Chemotaxis was assayed in a 48-well Boyden chamber (Neuprobe Microchemotaxis System) using 5 μM polyvinylpyrrolidone-free polycarbonate filters, as described earlier (Cabin John, MD).24 Inducers of neutrophil chemotaxis were added to the bottom wells as described in the figure legends. Hemin was added in the presence or in the absence of 1% human serum albumin. Neutrophils suspended in RPMI-1640 medium (106 cells/mL; 50 μL) were added to the top wells and incubated for 60 minutes at 37°C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Following incubation, the filters were removed from the chambers, fixed, and stained with a Diff-Quick stain kit (Baxter Travenol Labs, ON, Canada). Neutrophils that migrated to the bottom of the filters were counted using a 100× objective in at least 5 randomly chosen fields. Results were representative of 3 different experiments performed in triplicate for each sample. Neutrophil migration toward RPMI-1640 medium alone (random chemotaxis) was used as a negative control.

Actin content of cytoskeleton

Cytoskeleton fractions were derived from human neutrophils treated as indicated in the figure legends. Briefly, suspensions of 5 × 106 cells/mL were washed 3 times with ice-cold PBS and lysed in 50 mM morpholinoethanol sulfonide (MES) buffer, pH 6.4, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), 1 μg/mL DNase, 0.5 μg/mL RNase, and the following protease inhibitors: 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM benzamidine, 1 μM aprotinin, 1 μM leupeptin, and 1 μM soybean trypsin inhibitor (Sigma). After centrifugation at 13 000gfor 10 minutes at 25°C, supernatants were collected and pellets were suspended in the same buffer under vigorous agitation. Protein content of both pellets and supernatants was determined by the Bradford method.25 Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer was added and fractions were boiled for 3 minutes; 30-mg protein samples were separated on 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).26 After that, proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose sheet (Hybond-C Extra; Amersham Life Science), followed by incubation with Tween-TBS (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20) containing 1% bovine serum albumin. Actin was probed by overnight incubation at 4°C with monoclonal anti–α-actin antibody (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). After extensive washing in Tween-TBS, nitrocellulose sheets were incubated with anti-mouse IgG antibody conjugated to biotin (1:1000; Sigma) for 1 hour and then incubated with streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase (1:1000; Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Immunoreactive proteins were visualized by 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma) staining.

Assays of superoxide generation

Nitroblue tetrazolium reduction.

To observe superoxide production, we incubated human PMNs (106 cells/mL) with 0.05% nitroblue tetrazolium reduction (NBT) (Sigma) in DMEM in the presence or absence of phorbol 14-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; Sigma) or hemin for 1 hour at 37°C. After that, cells were cytocentrifuged onto glass slides, stained with 1% safranin (Sigma),27 and observed under a light microscope. Cells showing formazan deposits were counted in at least 5 random fields. Results were representative of 3 independent experiments.

Cytochrome c reduction.

The production of superoxide by human neutrophils was also measured by the superoxide dismutase–inhibitable reduction of ferricytochromec (Sigma), as previously described.28 Briefly, PMNs (106 cells/mL) were preincubated for 5 minutes with or without 100 μM diphenyleneiodonium (DPI; Sigma) in DMEM. The cells were then stimulated with heme at different concentrations, as described in the figure legend. Cytochrome c reduction was quantified 30 minutes later as an increase inA550(ε550 = 21 × 103 M−1 · cm−1). Results were representative of 3 different experiments performed in triplicate.

Neutrophil PKC activity

Human neutrophils (2 × 105 cells/microtube) were treated for 30 minutes with different concentrations of hemin, as indicated in the figure legends. After that, cells were quickly disrupted by sonication in 0.5 M sucrose, 5 mM ethyleneglycoltetraacetic acid (EGTA), 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.1% Triton X-100 and centrifuged at 40 000 rpm for 10 minutes to remove cell debris, and the supernatant was immediately used for enzyme activity determination. PKC activity was measured by [γ32P]-adenosine triphosphate (ATP) phosphorylation of myelin basic protein (MBP4-14; Calbiochem) substrate peptide in the presence or absence of 10 nM bis-indoylmaleimide III (BIM; Calbiochem). Briefly, a 20-μL aliquot of the previously centrifuged cell lysate was added to 80 μL reaction buffer containing 12.5 mM HEPES (4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid) (pH 8.0), 12.5 mM magnesium acetate, 0.4 mM calcium chloride, 0.1 mg/mL MBP4-14 peptide, and 20 μg phosphatidylserine. Reactions were started by the addition of [γ32P]-ATP to a final concentration of 10 μM (500-1000 cpm/pmol). After 5 minutes at 30°C, 25-μL aliquots of the reaction medium were transferred to a phosphocellulose filter and washed 3 times for 15 minutes each with ice-cold 20% trichloroacetic acid. Incorporated radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation. Each treatment was assayed in duplicate. Background reactions to determine nonspecific phosphorylation received the same components except for phosphatidylserine, which was replaced by 5 mM EGTA.

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction analysis of IL-8 transcripts

Neutrophils (5 × 106 cells) were incubated for 4 hours with different effectors, as indicated in the figure legend. Total RNA was then extracted with the QuickPrep RNA extraction kit (Amersham Pharmacia) following the manufacturer's instructions. Semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed basically according to the reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) kit from Perkin-Elmer. RT-PCR for IL-8 expression was performed with primerIL-8for (5′-TGGCTCTCTTGGCAGCCTTC-3′) and primerIL-8rev (5′-TCTCCACAACCCTCTGCACC-3′). Control reactions were performed with primers GAP1for(5′-GGTGAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGA-3′) and GAP2rev(5′-GAGGGATCTCGCTCCTGGAAGA-3′), which are specific for the human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Conditions for PCR were: 94°C, 1 minute; 50°C, 1 minute; and 72°C, 40 seconds. To achieve quantitative amplification of IL-8 transcripts, we used 18 cycles to keep the reaction within its exponential phase. All reactions were carried out in the presence of 1 μCi (0.037 MBq) α[32P]-CTP per tube. The amplification products were separated using 8% PAGE, dried, and exposed to Kodak X-Omat film. Data are presented as the ratio of IL-8 to GAPDH product obtained by densitometry from the autoradiograms (BioImager; BioRad).

Results

Hemin induces neutrophil migration in vivo and in vitro

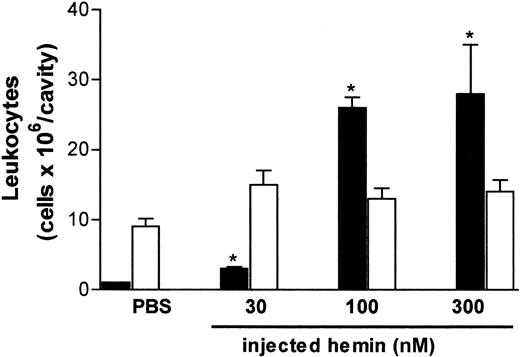

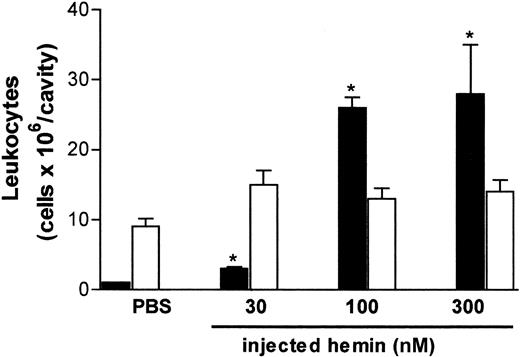

The effect of hemin on neutrophil recruitment was investigated in vivo and in vitro using different experimental approaches. As illustrated in Figure 1, free hemin can promote neutrophil recruitment in vivo. The intrathoracic administration of hemin induced a dose-dependent neutrophil accumulation in rat pleural cavities, which was observed 4 hours after the injection. The stimulatory effect was already evident with 30 nmol/cavity and increased 7-fold at the highest dose administered (300 nmol/cavity). Four hours after hemin injection, only the pleural neutrophil population was increased, and no changes in the number of mononuclear cells were observed.

Hemin induces rat neutrophil migration in vivo.

Hemin (30-300 nmol) was injected into the thoracic cavity of rats as described in “Materials and methods.” The control group received sterile PBS. Animals were killed 4 hours after injection, and total leukocytes in the pleural fluid were determined on Neubauer chambers. Differential counting of neutrophils (black bars) and mononuclear cells (white bars) was carried out on May-Grünwald-Giemsa–stained slides. Results are expressed as millions of cells per cavity. Each bar is the mean ± SD from at least 4 animals. *P < .01.

Hemin induces rat neutrophil migration in vivo.

Hemin (30-300 nmol) was injected into the thoracic cavity of rats as described in “Materials and methods.” The control group received sterile PBS. Animals were killed 4 hours after injection, and total leukocytes in the pleural fluid were determined on Neubauer chambers. Differential counting of neutrophils (black bars) and mononuclear cells (white bars) was carried out on May-Grünwald-Giemsa–stained slides. Results are expressed as millions of cells per cavity. Each bar is the mean ± SD from at least 4 animals. *P < .01.

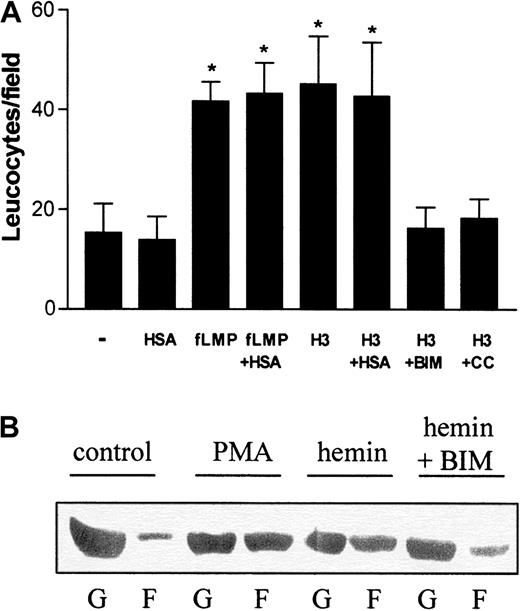

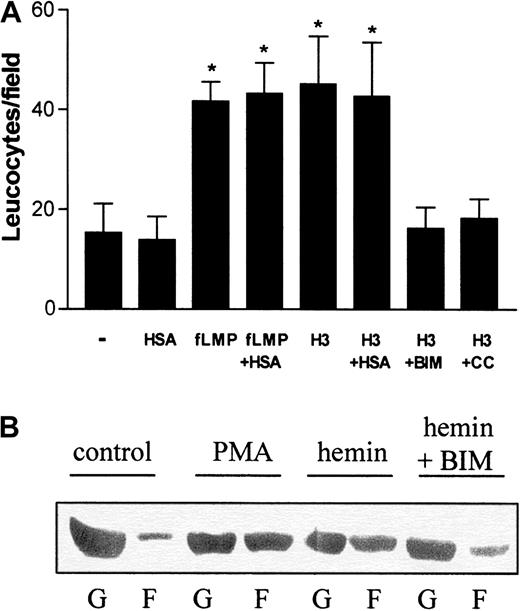

On the basis of these results, we investigated whether hemin could also directly stimulate neutrophil migration in vitro. For these studies, human PMNs were allowed to migrate toward hemin in a Boyden chamber. Because albumin is a plasma constituent able to bind heme, we checked whether the presence of 150 μM human serum albumin (HSA) would modify neutrophil recruitment. The binding constant of the association of hemin to HSA is 3.6 × 107M−1,29 and therefore, under our experimental conditions, all hemin added to the medium should be associated with albumin. Hemin induced the chemotaxis of human neutrophils (Figure2A), and this induction was also observed in the presence of HSA. This chemotactic effect was already noted with 1 μM hemin (data not shown), reaching a 4-fold induction at 3 μM compared with the control group (Figure 2A). In addition, when hemin was added together with BIM, a potent and selective inhibitor of PKC,30 an almost complete inhibition of the hemin-stimulated migration was observed, suggesting that PKC activation is required for neutrophil recruitment by hemin. Another PKC inhibitor, calphostin C, also inhibited heme-induced neutrophil migration.

Hemin induces human neutrophil chemotaxis and actin polymerization.

(A) The effect of hemin on neutrophil chemotaxis was evaluated in a Boyden chamber. To stimulate PMN chemotaxis, we added either 10−7 M N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine, 3 μM hemin (H3), 3 μM hemin + 10 nM BIM (H3 + BIM), or 3 μM hemin + 50 nM calphostin C (H3 + CC) to the bottom wells. Some groups were stimulated to migrate in the presence of 1% human serum albumin (+HSA). Neutrophils were added to the top wells and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C under 5% CO2. After that, the filter was removed from the chamber and processed for neutrophil quantification as described in “Materials and methods.” Results are expressed as mean ± SD and are representative of 3 different experiments performed in triplicate for each sample. *P < .01. (B) Neutrophils were treated for 1 hour with 10 μM hemin in the presence (hemin + BIM) or absence (hemin) of 10 nM BIM or 100 nM PMA (PMA). The control group received only vehicle as treatment (control). After that, cells were lysed and the presence of actin in the Triton-soluble cytosolic fraction (G) and in the Triton-insoluble cytoskeleton fraction (F) was analyzed in each group by Western blot.

Hemin induces human neutrophil chemotaxis and actin polymerization.

(A) The effect of hemin on neutrophil chemotaxis was evaluated in a Boyden chamber. To stimulate PMN chemotaxis, we added either 10−7 M N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine, 3 μM hemin (H3), 3 μM hemin + 10 nM BIM (H3 + BIM), or 3 μM hemin + 50 nM calphostin C (H3 + CC) to the bottom wells. Some groups were stimulated to migrate in the presence of 1% human serum albumin (+HSA). Neutrophils were added to the top wells and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C under 5% CO2. After that, the filter was removed from the chamber and processed for neutrophil quantification as described in “Materials and methods.” Results are expressed as mean ± SD and are representative of 3 different experiments performed in triplicate for each sample. *P < .01. (B) Neutrophils were treated for 1 hour with 10 μM hemin in the presence (hemin + BIM) or absence (hemin) of 10 nM BIM or 100 nM PMA (PMA). The control group received only vehicle as treatment (control). After that, cells were lysed and the presence of actin in the Triton-soluble cytosolic fraction (G) and in the Triton-insoluble cytoskeleton fraction (F) was analyzed in each group by Western blot.

Hemin induces alterations in actin cytoskeleton dynamics

Motile activities of neutrophils (chemotaxis and phagocytosis) are generated by dynamic alterations of actin filaments. Under resting conditions, human PMNs exhibit a high content of unpolymerized actin (G-actin), whereas the polymerized actin (F-actin), associated with the Triton-insoluble cytoskeleton fraction, is almost undetectable (Figure2B; control). Incubation with PMA increased actin polymerization, decreasing G-actin content (Figure 2B; PMA). It is clear that hemin induced alterations in actin cytoskeleton dynamics similar to those generated by incubation with PMA (Figure 2B; hemin). However, in the presence of BIM (Figure 2B; hemin + BIM), hemin-induced actin polymerization was prevented, and cells showed a G/F-actin profile similar to that in the control group.

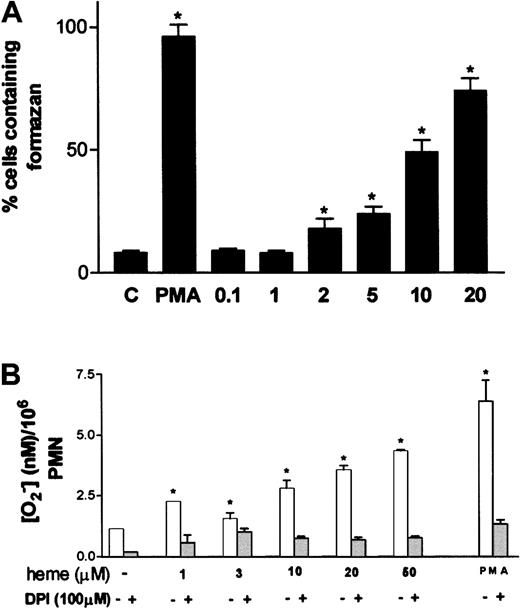

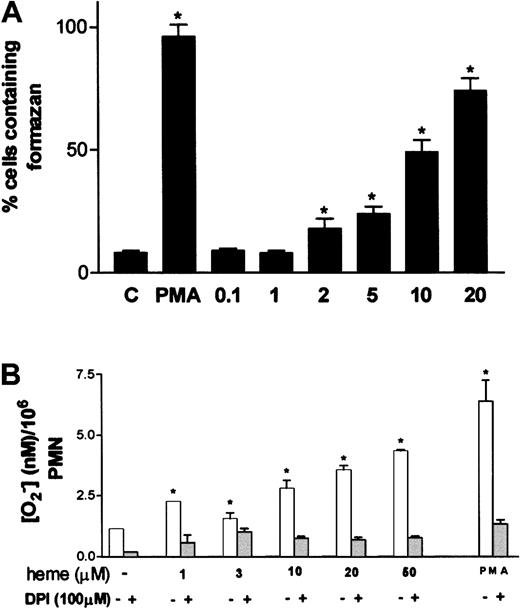

Hemin induces superoxide production by human neutrophils

One of the most characteristic aspects of phagocyte activation is the increase in the production of superoxide anion, the so-called oxidative burst. Stimulation of neutrophils by hemin resulted in increased superoxide formation, assessed through the intracellular precipitation of the insoluble formazan crystals induced by the reduction of NBT by superoxide (Figure3A). Activation of superoxide production by hemin was already noted at 2 μM hemin, reaching maximal values at 20 μM, at which point 70% of the cells presented intracellular formazan crystals. Incubation of neutrophils with 30 nM PMA, used as routine positive control, resulted in 96% of cells producing formazan, compared with the control group incubated in medium alone, in which only 8% of the cells were activated. The ability of hemin to trigger the oxidative burst in neutrophils was further investigated using the method of Pick and Mizel,28 with minor modifications. When neutrophils were incubated with hemin, superoxide production increased up to 4.4-fold in a hemin dose–dependent fashion (Figure 3B), confirming that hemin can induce the oxidative burst in human PMNs. Preincubation of neutrophils with the NADPH oxidase inhibitor DPI abrogated superoxide production evoked by hemin, suggesting that the stimulatory effect promoted by hemin was actually on the NADPH oxidase system.

Oxidative burst in human neutrophils is triggered by hemin.

(A) Human PMNs were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C with hemin (0.1-20 μM) or 100 nM PMA in the presence of 0.05% NBT. After that, cells were stained with safranin, and formazan deposits were quantified under a light microscope. At least 5 random fields were analyzed per data point. Data shown are from a typical experiment, representative of 3 identical studies. *P < .01. (B) Intracellular production of superoxide was evaluated through the reduction of cytochromec. Neutrophils were incubated with distinct amounts of heme in the presence or absence of DPI. PMA (100 nM) was used as a positive control for superoxide production. Incubations were carried out at 37°C for 30 minutes. Data shown are from a typical experiment, representative of 3 identical studies performed in triplicate. *P < .01.

Oxidative burst in human neutrophils is triggered by hemin.

(A) Human PMNs were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C with hemin (0.1-20 μM) or 100 nM PMA in the presence of 0.05% NBT. After that, cells were stained with safranin, and formazan deposits were quantified under a light microscope. At least 5 random fields were analyzed per data point. Data shown are from a typical experiment, representative of 3 identical studies. *P < .01. (B) Intracellular production of superoxide was evaluated through the reduction of cytochromec. Neutrophils were incubated with distinct amounts of heme in the presence or absence of DPI. PMA (100 nM) was used as a positive control for superoxide production. Incubations were carried out at 37°C for 30 minutes. Data shown are from a typical experiment, representative of 3 identical studies performed in triplicate. *P < .01.

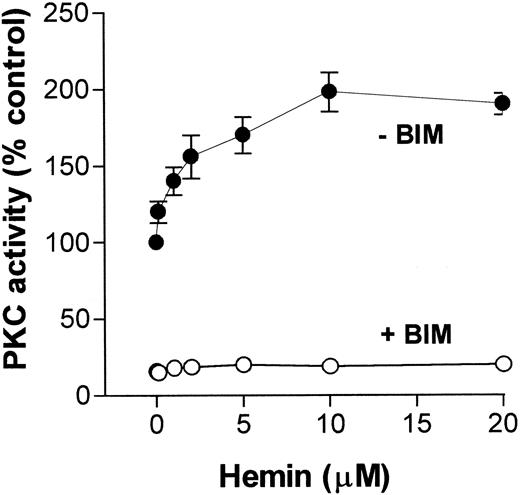

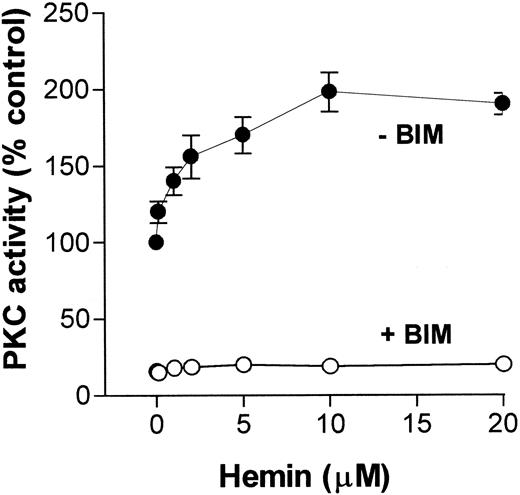

Hemin activates human neutrophil PKC

Because migration and superoxide production by neutrophils are functions that can be modulated by a PKC pathway, and on the basis of our previously published data showing that hemin stimulated PKC activity in an insect cell,31 we investigated whether hemin could also activate PKC in neutrophils. To address this question, we incubated human neutrophils with hemin (0.1-20 μM) and evaluated PKC activity through phosphorylation of MBP peptide. As shown in Figure4, PKC activity stimulation by hemin was dose-dependent, with a K1/2 of 5 μM, and was prevented by BIM, indicating that the PKC up-regulation observed with the insect model also occurs in human neutrophils.

Hemin activates human neutrophil PKC.

Human neutrophils were incubated for 30 minutes in the presence of different concentrations of hemin, as indicated on the abscissa. After that, cells were ruptured as described in “Materials and methods,” and PKC activity was determined in the cytosolic fraction in the presence (+BIM) or absence (-BIM) of 10 nM BIM. Results are expressed as a percentage of the control activity, determined from cells treated with 0.01% DMSO. Data are presented as mean ± SD from 2 different experiments performed in triplicate.

Hemin activates human neutrophil PKC.

Human neutrophils were incubated for 30 minutes in the presence of different concentrations of hemin, as indicated on the abscissa. After that, cells were ruptured as described in “Materials and methods,” and PKC activity was determined in the cytosolic fraction in the presence (+BIM) or absence (-BIM) of 10 nM BIM. Results are expressed as a percentage of the control activity, determined from cells treated with 0.01% DMSO. Data are presented as mean ± SD from 2 different experiments performed in triplicate.

Hemin activates IL-8 expression in human neutrophils

Recruitment of neutrophils into inflammatory sites can be modulated by the presence of several chemokines. One of the most important chemoattractants for neutrophils is the cytokine IL-8, which also stimulates adhesion, respiratory burst, and degranulation.32 To investigate an additional parameter of neutrophil activation, we evaluated the mRNA levels of IL-8 in cells treated with hemin. Incubation of human neutrophils with 3 μM heme resulted in a 40-fold increase in IL-8 expression compared with the control group (Figure 5). When heme was added in the presence of albumin, induction of IL-8 expression was also observed, but to a lesser extent, suggesting that binding of heme to plasma components can modulate the biologic effects of this molecule. In contrast to the effects on recruitment and oxidative burst, induction of IL-8 expression promoted by hemin was not reversed in the presence of BIM, ruling out the participation of PKC in this phenomenon. As a positive control of IL-8 expression, neutrophils were incubated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and produced the expected increase in mRNA.

The expression of IL-8 mRNA in human neutrophils following exposure to hemin.

Neutrophils (5 × 106 cells) were incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C with 3 μM hemin in the presence (H3 + HSA) or absence (H3) of 1% human serum albumin, or in the presence of 10 nM BIM (H3 + BIM). Control groups received only PBS (control) or albumin (HSA) as treatment. For positive IL-8 transcript production, cells were treated with 10 ng/mL LPS. After that, cells were washed 2 times with PBS and incubated for 4 hours in RPMI. Total cellular RNA was isolated, and RT-PCR was performed using IL-8 and GAPDH-specific probes in the presence of α[32P]-CTP. Data are presented as the ratio between the expression of IL-8 to GAPDH levels. For additional information, see “Materials and methods.” This representative experiment was repeated 3 times, showing similar results. Data are reported as cumulative data in the form of mean ± SD. *P < .01.

The expression of IL-8 mRNA in human neutrophils following exposure to hemin.

Neutrophils (5 × 106 cells) were incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C with 3 μM hemin in the presence (H3 + HSA) or absence (H3) of 1% human serum albumin, or in the presence of 10 nM BIM (H3 + BIM). Control groups received only PBS (control) or albumin (HSA) as treatment. For positive IL-8 transcript production, cells were treated with 10 ng/mL LPS. After that, cells were washed 2 times with PBS and incubated for 4 hours in RPMI. Total cellular RNA was isolated, and RT-PCR was performed using IL-8 and GAPDH-specific probes in the presence of α[32P]-CTP. Data are presented as the ratio between the expression of IL-8 to GAPDH levels. For additional information, see “Materials and methods.” This representative experiment was repeated 3 times, showing similar results. Data are reported as cumulative data in the form of mean ± SD. *P < .01.

Discussion

Hemorrhagic episodes and severe hemolysis are often associated with tissue injury that can trigger the inflammatory response characterized by intense leukocyte infiltration. We show here that heme can promote neutrophil migration in vivo, suggesting a direct proinflammatory effect of this blood component. The heme toxicity may arise in environments where there is pronounced hemolysis, for instance, localities exposed to high erythrocyte shear forces or turbulent blood flow. Very high heme plasma levels (>20 μM) have been reported in hemolytic diseases such as sickle cell anemia.33 The demonstration that hemopexin levels are decreased in patients with a variety of hematologic disorders suggests the importance of other plasma constituents able to bind heme during hemolytic episodes.34 Although albumin is capable of drawing hemin away from red cell membranes, the detection of heme–albumin complexes portends an extremely poor prognosis for patients with life-threatening hemorrhagic shock.35

In our experiments with rats, intrathoracic injection of hemin induced an acute inflammatory reaction, characterized by edema formation (data not shown) and intense accumulation of neutrophils in the pleural cavities. The stimulation of neutrophil migration in vivo and in vitro reported here suggests that free heme has the potential to serve as an endogenous chemoattractant. Association of hemin with human albumin did not reduce its propensity to promote neutrophil migration. This is consistent with the fact that binding of heme to albumin36does not prevent heme uptake, and therefore, after dissociation, heme will eventually diffuse into circulating and endothelial cells.

A primary event in the inflammatory response is the recruitment of neutrophils into sites of inflammation. In vivo or in vitro, leukocyte migration induced by different chemoattractants is promptly stimulated by phorbol esters, indicating that PKC stimulation can lead to neutrophil chemotaxis. In our experiments, the PKC inhibitors BIM and calphostin C efficiently blocked neutrophil migration induced by hemin in vitro, consistent with a link between migration and PKC.

Another important event in the inflammatory response is the production of ROS by activated phagocytes. We show in the present study that hemin triggers the oxidative burst and promotes actin polymerization in human PMNs, indicating that hemin is a potent neutrophil activator such as formyl peptides, IL-8, platelet activation factor, and C5a.37

Incubation with hemin induced profound alterations in the actin network and an increase of F-actin content. This event seems to be related to the PKC activation promoted by hemin because the PKC inhibitor BIM counteracts this hemin-induced actin polymerization. Thus, it is conceivable to suggest that hemin triggers human neutrophils by means of PKC up-regulation. Incubation of human neutrophils with hemin promptly activated PKC in a concentration-dependent manner, and this effect was completely inhibited by a selective PKC inhibitor. This is consistent with our previous report, in which heme was shown to be a potent activator of PKC in an insect cell model.31

We are currently investigating the molecular basis of the PKC activation reported here. Because of its highly hydrophobic nature and considering that at neutral pH, the 2 lateral carboxyl groups of hemin are dissociated, we believe that a possible explanation for the PKC activator effect reported here might be interaction of hemin carboxyl groups with the phospholipid-binding regulatory domains of the enzyme. However, an indirect effect, such as oxidation of regulatory and/or binding domains, should not be discarded because it has been shown that PKC can be activated by superoxide anion, redox cycling quinones, and micromolar levels of periodate.38 39

Because hemin was able to activate PKC in PMNs, a possible direct implication is the modulation of PKC-related gene expression. Expression of proinflammatory and immunoregulatory cytokines rapidly increases in the lung after hemorrhage,40 but the specific agent responsible for the onset of these proinflammatory responses remains unknown. It was recently shown that hemin can boost the expression of α2-macroglobulin after systemic inflammation induced by LPS, indicating a possible role for heme in the expression of positive acute-phase proteins.41

We also investigated whether hemin could modulate the expression of inflammatory mediators by human neutrophils. A key mediator for the migration of neutrophils from the circulation is the α-chemokine IL-8, which acts mainly on neutrophils to trigger chemotaxis, respiratory burst, degranulation, and adhesion to endothelial cells. Under resting conditions, we were not able to find any constitutive expression of IL-8, whereas in the presence of PMA, a known activator of IL-8 transcription,42 we observed a very strong signal after 4 hours of incubation. We show here that expression of IL-8 is highly induced by hemin, but unlike the other effects studied in this paper, IL-8 expression was not reversed by the PKC inhibitor BIM. This finding indicates that the induction of this chemokine by hemin is a PKC-independent event, and it may be that hemin can be involved in the modulation of multiple pathways rather than acting only as a PKC modulator. Less markedly, IL-8 expression promoted by hemin was also observed in the presence of human albumin.

Taken together, the data reported here are consistent with the assumption that hemin could act as a signaling molecule involved in the triggering of inflammatory processes often associated with hemolysis.

We express our gratitude to Dr Patrı́cia T. Bozza and Martha Sorenson for a critical reading of the manuscript and to Rosane M. M. Costa and S. R. Cássia for the excellent technical assistance.

Supported by grants from the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientı́fico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Coordenadoria de Aperfeiçoamento do Pessoal de Nı́vel Superior (CAPES), Financiadora de Estudos e Projetos (Finep), Programas de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento Cientı́fico e Tecnológico (PADCT), Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, Fundação de Apoio a Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ), and Programa de Núcleos de Excelência (PRONEX).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Aurélio V. Graça-Souza, Departamento de Farmacologia, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; e-mail: avsouza@bioqmed.ufrj.br.

![Fig. 5. The expression of IL-8 mRNA in human neutrophils following exposure to hemin. / Neutrophils (5 × 106 cells) were incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C with 3 μM hemin in the presence (H3 + HSA) or absence (H3) of 1% human serum albumin, or in the presence of 10 nM BIM (H3 + BIM). Control groups received only PBS (control) or albumin (HSA) as treatment. For positive IL-8 transcript production, cells were treated with 10 ng/mL LPS. After that, cells were washed 2 times with PBS and incubated for 4 hours in RPMI. Total cellular RNA was isolated, and RT-PCR was performed using IL-8 and GAPDH-specific probes in the presence of α[32P]-CTP. Data are presented as the ratio between the expression of IL-8 to GAPDH levels. For additional information, see “Materials and methods.” This representative experiment was repeated 3 times, showing similar results. Data are reported as cumulative data in the form of mean ± SD. *P < .01.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/99/11/10.1182_blood.v99.11.4160/6/m_h81122605005.jpeg?Expires=1768582050&Signature=Jq2lCnsyWFvAgPO3BsDPd1S4UbubOersRLIkf-~153bt6dPAOU6jMeouULGPtgZu0iga5bjmmnW0c6Aq-1xgQyx6baoMONtk~z2Xc9~Mn2RG2P8XoROvEU5rg58xjc9Djq5tzJpFvOAieM3oQxtDonehmxZACYAXLGmPzqk32DpQkeRFDtMQU0yDCoSVAAKVd47PqJDdway6rNxta6zfog7eVpl5gRojxcu81UhvKsorQ~brd7XbnSmRPKFHFsM6UDnNzfvOQjE9YzLZ0gHKQ5oShvtjEakZAFO-QHn-2FQgnDXLfPjanfvEtzgYoWoG8HzGknaUvsuq7OYtrYVrqw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 5. The expression of IL-8 mRNA in human neutrophils following exposure to hemin. / Neutrophils (5 × 106 cells) were incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C with 3 μM hemin in the presence (H3 + HSA) or absence (H3) of 1% human serum albumin, or in the presence of 10 nM BIM (H3 + BIM). Control groups received only PBS (control) or albumin (HSA) as treatment. For positive IL-8 transcript production, cells were treated with 10 ng/mL LPS. After that, cells were washed 2 times with PBS and incubated for 4 hours in RPMI. Total cellular RNA was isolated, and RT-PCR was performed using IL-8 and GAPDH-specific probes in the presence of α[32P]-CTP. Data are presented as the ratio between the expression of IL-8 to GAPDH levels. For additional information, see “Materials and methods.” This representative experiment was repeated 3 times, showing similar results. Data are reported as cumulative data in the form of mean ± SD. *P < .01.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/99/11/10.1182_blood.v99.11.4160/6/m_h81122605005.jpeg?Expires=1768582051&Signature=t7wkTXB7zQFCmgNY1bVyk2-zXlFbS~A2lafOakl5Aq31bkdXBCqigL5yUvZEEwLo12hbPD3h6cZLl0XFWeDjbPWh9~82QRN0uDrqH-9JZbrzoD62rlVfp7p-YSQKP8NdmGEA6vkWq2tzuOtNWnpSz3fk494VOEEJy4ZL11woYdS4QzJQ24POnG3R~qQ1FaX8IFGTbmWs-pIJRmxpXBgk6oOYtzcKtmCdY1IdZ~XI~AGlkd3sCF3OzEM9TZIbK9ni5jCnb~7lK8tIdQ5T~v34gYst9bQknxuyLSPd1lnpdIcMZCx3P9yL4azom6QiRRRTRwUsDDj~MbI5k9a5EEQmfA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)