Abstract

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common indication for transplantation of marrow from unrelated donors in children. We analyzed results of this procedure in children with ALL treated according to a standard protocol to determine risk factors for outcome. From January 1987 to 1999, 88 consecutively seen patients with ALL who were younger than 18 years received a marrow transplant from an HLA-matched (n = 56) or partly matched (n = 32) unrelated donor during first complete remission (CR1; n = 10), second remission (CR2; n = 34), third remission (CR3; n = 10), or relapse (n = 34). Patients received cyclophosphamide and fractionated total-body irradiation as conditioning treatment and were given methotrexate and cyclosporine for graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis. Three-year rates of leukemia-free survival (LFS) according to phase of disease were 70% for CR1, 46% for CR2, 20% for CR3, and 9% for relapse (P < .0001). Three-year cumulative relapse rates were 10%, 33%, 20%, and 50%, respectively, and 3-year cumulative rates of death not due to relapse were 20%, 22%, 60%, and 41%, respectively, for patients with CR1, CR2, CR3, and relapse. Grades III to IV acute GVHD occurred in 43% of patients given HLA-matched transplants and in 59% given partly matched transplants (P = .10); clinical extensive chronic GVHD occurred in 32% and 38%, respectively (P = .23). LFS rates were lower in patients with advanced disease (P < .0001), age 10 years or older (P = .002), or short duration of CR1 (P = .007). Thus, in addition to phase of disease, age and duration of CR1 were predictors of outcome after unrelated-donor transplantation for treatment of ALL in children. Outcome was particularly favorable in younger patients with early phases of the disease.

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common indication for marrow transplantation in children. Marrow transplantation has been restricted to treatment of advanced or high-risk ALL, since conventional chemotherapy provides excellent control of the disease in most newly diagnosed patients. For patients with relapse, transplantation of marrow from HLA-matched sibling donors during second complete remission (CR2) has been reported to provide leukemia-free survival (LFS) rates of 40% to 50% at 2 to 5 years.1,2 The role of marrow transplantation in treatment of patients with high-risk features in first complete remission (CR1) has not been established. Single-arm studies of HLA-identical, sibling-donor marrow transplantation during CR1 in patients with ALL and very high-risk features found LFS rates of 45% to 84% at 3 years, indicating an apparent survival advantage for this treatment compared with conventional chemotherapy.3-5

The development of donor registries has increased the availability of HLA-matched or closely matched donors for the 70% of patients without an HLA-matched family-member donor. Compared with historical controls, results with unrelated-donor (URD) marrow transplants have approached those with transplants from HLA-matched sibling.1,6-9Several factors have been associated with improved survival, including transplantation during an early phase of the disease, HLA matching, and high marrow cell dose.9-13 However, studies of this issue generally included adult patients, and prognostic factors associated with pediatric ALL were not found to be significant. The objective of this study was to identify risk factors in children with ALL who underwent URD marrow transplantation according to a standard protocol in a single institution. For this purpose, we analyzed the subgroup of patients with a diagnosis of ALL who were younger than 18 years at the time of transplantation and who received an URD marrow graft and a standard conditioning regimen.

Patients and methods

Patients

Beginning in April 1983, a standard protocol was used for URD marrow transplantation in patients with hematologic malignant disease. Patients were eligible if they had a diagnosis of high-risk hematologic disease and a suitable URD. Patients were excluded if they were older than 55 years, had a life expectancy severely limited by organ dysfunction or diseases other than cancer, had leukoencephalopathy, had received more than 3000 cGy in irradiation to the whole brain or more than 1500 cGy to the chest or abdomen, or were seropositive for human immunodeficiency virus. Among patients enrolled in the study, we confined the analysis described here to those with a diagnosis of ALL who were under 18 years of age at the time of transplantation and who received a transplant before January 1999. Eighty-eight children fit these criteria.

The diagnosis of ALL was made at the referring institution and confirmed by review of diagnostic bone marrow samples. Primary and secondary therapies for ALL varied according to practice at the referring institution. Remission status was determined within 2 weeks before transplantation by histopathological and cytogenetic analysis of marrow and cerebrospinal fluid. Remission was defined as a complete response to chemotherapy in the bone marrow, that is, less than 5% blasts and normal marrow cellularity or a true M1 marrow; absence of these findings was considered a relapse. For consistency with previous studies in our institution, disease phase was first defined according to the number of medullary remission or relapse events that occurred before transplantation, and an isolated extramedullary relapse was not considered a separate relapse event. Outcomes also were analyzed by using a more standard definition of disease phase that included extramedullary relapse as an event.

Treatment

The preparative regimen consisted of administration of cyclophosphamide (60 mg/kg of body weight per day for 2 days; total dose, 120 mg/kg) followed by total-body irradiation (TBI) delivered from opposing cobalt sources in 3 daily fractions of 120 cGy each (total dose, 14.4 Gy).9 From 1987 to 1989, younger patients with leukemia relapse received a 15.75-Gy total dose of TBI given in daily fractions of 2.25 Gy. Patients received 2 intrathecal injections of methotrexate during the preparative phase, and male patients received an addition 4.0 Gy of irradiation to the testes. Additional irradiation was used to treat active sites of extramedullary disease (EMD). The transplantation protocols and consent forms were approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (FHCRC) and Children's Hospital and Regional Medical Center, and informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from parents or guardians in accordance with IRB policies.

Histocompatibility testing of all patients and donors was done by the Clinical Immunogenetics Laboratory at FHCRC using methods described previously.14,15 Until 1990, compatibility of the HLA-D region was defined by determining the Dw phenotype using HLA-D homozygous typing cells.14,15 Subsequently, hybridization of sequence-specific oligonucleotide probes was used to identify DRB1 alleles.16 Patient-donor compatibility was tested further by lymphocyte cross-matching (patient serum versus donor T and B cells) before transplantation.17 Donors were HLA matched or had incompatibility of one HLA locus, defined as a disparity within a cross-reactive group for the HLA-A or HLA-B locus, or within the same serologically defined DR specificity for HLA-Dw antigens or DRB1 alleles.

Patients received unmanipulated bone marrow cells collected according to established methods18,19 infused through a central venous catheter on day 0 within 24 hours after the last dose of irradiation. Methotrexate (MTX) and cyclosporine (CSP) were given for prevention of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).9 During 1993 and 1994, some patients were enrolled in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of daclizumab in addition to receiving standard prophylaxis with MTX and CSP.20 Patients had indwelling central venous catheters and received nutritional support by means of intravenous hyperalimentation. Measures to prevent infection varied according to the standard of practice at the time of transplantation, and included use of single conventional or laminar airflow rooms, growth factors, and intravenous immunoglobulin, and beginning in 1992, prophylactic fluconazole21 and ganciclovir if indicated for cytomegalovirus prophylaxis.22 23

Engraftment was defined as achievement of a peripheral granulocyte count above 500 cells/μL for 3 consecutive days. Patients were not considered evaluable for engraftment if they died and did not have a granulocyte count above 500 cells/μL before day 21. Donor engraftment was determined by in situ DNA hybridization with a Y-body–specific probe24 (sex-mismatched transplants), by analysis of restriction fragment-length polymorphisms,25 or by polymerase chain reaction assay of genomic DNA for variable-number tandem-repeat polymorphisms.26 Acute and chronic GVHD were diagnosed according to conventional criteria and treated as described previously.18,27 28 Patients were not considered evaluable for acute GVHD if they died before engraftment or for chronic GVHD if they died before day 80 after transplantation.

Statistical methods

Proportional hazards regression models were fit for the following end points: relapse, nonrelapse-related death (NRD), and LFS (death or relapse, whichever occurred first, was considered an event). Explanatory variables examined were patient age at diagnosis, age at transplantation (< 10 years versus ≥ 10 years), ethnic group (white versus nonwhite), EMD any time before transplantation, immunophenotype (defined as B-cell precursor [CD10+] versus T-cell or null cell [CD10−]), cytogenetic abnormalities (normal versus hyperdiploidy versus t(4;11) or t(9;22) or hypodiploidy versus other abnormal cytogenetic findings versus unknown), white blood cell (WBC) count at diagnosis (< 10.0 × 109/L versus 10.0-50.0 × 109/L versus > 50.0 × 109/L), phase of disease at transplantation (CR1 versus CR2 versus third complete remission [CR3] versus relapse, examined both with extramedullary relapse included and excluded from the definition of CR1), duration of CR1 (≤ 24 months versus > 24 months), time from diagnosis to transplantation, patient and donor cytomegalovirus serologic status, patient and donor HLA match, patient and donor sex match, cell dose (< 3.65 × 108versus ≥ 3.65 × 108 total nucleated cells/kg), and year of transplantation (before 1992 versus 1992 and later, when standard infection prophylaxis was used in all patients). Peripheral blasts and the percentage of blasts in pretransplantation marrow were examined in patients with relapse at the time of transplantation.

Estimates of overall survival and LFS were calculated by using the method of Kaplan and Meier,29 and cumulative incidence estimates were used to describe rates of relapse and NRD.30 For the end point of relapse, death without relapse was regarded as a competing risk and conversely for NRD. In the regression models, patients not reaching the appropriate end point were censored at the time of last contact or failure because of a competing risk, whichever occurred first. All P values associated with the regression models were derived from the likelihood ratio test. Comparisons between patient groups were made with the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables. All P values are 2-sided. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons. Data collected by April 2001 were included in the analysis.

Results

Patient characteristics

Between July 1987 and January 1999, 88 consecutively seen children (< 18 years of age) with ALL were treated according to a standard protocol for URD marrow transplants. Two of these patients did not tolerate CSP and MTX for GVHD prophylaxis and received alternative prophylactic therapy, and 7 patients received daclizumab in addition to CSP and MTX prophylaxis. Patient characteristics at diagnosis and transplantation are shown in Table 1. Patients were considered in remission if a bone marrow aspirate had less than 5% marrow blasts and normal cellularity with trilineage hematopoiesis within 2 weeks of transplantation. Among patients considered to have relapse, 24 had more than 25% marrow blasts, 9 had 6% to 25%, and 1 had 5% at the time of transplantation. The last patient did not have remission after 2 reinduction regimens and underwent transplantation 9 days after a third attempt at reinduction without marrow recovery; therefore, this patient did not fulfill the criteria for remission. Among the remaining patients with relapse, 10 others did not have remission after reinduction chemotherapy given within 2 months of transplantation (2 with 6%-25% blasts and 8 with > 25% blasts in marrow at transplantation), and in 23 patients, the interval from last reinduction attempt to transplantation was longer than 2 months.

Patients with CR1 had several poor prognostic features, including age less than 9 months at diagnosis (2 patients), poor-risk cytogenetic findings (Philadelphia chromosome and t(4;11), 1 patient each), undifferentiated leukemia phenotype (1 patient), and poor response to induction therapy (1 patient). Four patients had multiple extramedullary relapses before transplantation but did not have a medullary relapse. These patients were considered twice, first by using the definition of CR1 that excluded extramedullary relapse and second by including extramedullary relapse in the definition of CR1. In this group, each patient had a first central nervous system (CNS) relapse within 24 months of diagnosis, followed by both a CNS and a testicular relapse in 2 patients and a CNS relapse that persisted despite systemic and local reinduction therapy in 1 patient. Among all patients, 40 had pretransplantation EMD that involved the CNS (27 patients), testes (9 patients), CNS and testes (3 patients), and CNS and skin (1 patient). Prophylactic cranial irradiation or radiation therapy to the site of EMD was given to 30 patients as part of initial or reinduction therapy before transplantation, and 10 patients received local radiation as a boost immediately before TBI.

LFS, relapse, and NRD

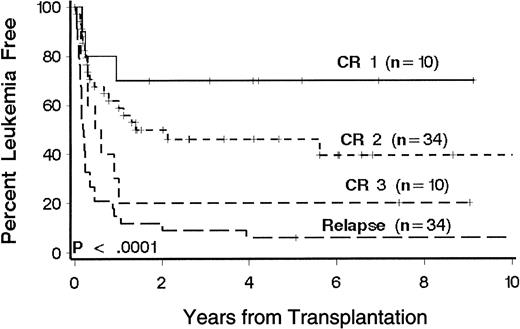

Twenty-eight patients (31%) were alive 1 to 10 years after transplantation. Sixty patients died, 29 of relapse and 31 of causes other than relapse (Table 2). Kaplan-Meier estimates of LFS at 3 years according to phase of disease at transplantation were 70%, 46%, 20%, and 9%, respectively, for patients with CR1, CR2, CR3, and relapse (Figure1). There was no appreciable difference when extramedullary relapses were considered relapse events (3-year LFS rates were 67%, 47%, 20%, and 9%, respectively;P < .0001). In the multivariate model, disease phase was significantly associated with the risk of death or relapse (P < .0001; Table 3). Multivariate analysis showed that age, immunophenotype, and duration of CR1 were significantly associated with the risk of death or relapse (Table 3). T-cell and null-cell immunophenotype were associated separately with a lower risk of relapse and therefore were grouped together for comparison with pre-B cell immunophenotype in the multivariate analysis. Favorable factors include age less than 10 years, CR1 duration of more than 24 months, and T-cell or null-cell immunophenotype. Patients with CR2 who were younger than 10 years at transplantation had a 3-year LFS of 61%. Among patients with relapse at transplantation, there was no significant association between percentage of marrow blasts or presence of circulating blasts and the risk of death or relapse.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of LFS in 88 patients with ALL according to phase of disease at transplantation.

Phase of disease was defined by the number of medullary relapses. Significance was determined by log rank test. Censored patients are indicated by hatch marks.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of LFS in 88 patients with ALL according to phase of disease at transplantation.

Phase of disease was defined by the number of medullary relapses. Significance was determined by log rank test. Censored patients are indicated by hatch marks.

Recurrent leukemia occurred in 31 patients. Relapse rates according to phase of disease at transplantation were 10%, 33%, 20%, and 50%, respectively, for patients with CR1, CR2, CR3, and relapse. In the multivariate models (Table 3), disease phase was significantly associated with the risk of relapse. There was no appreciable difference when extramedullary relapses were considered relapse events (3-year relapse rates were 11%, 32%, 20%, and 50%, respectively;P = .0006). Additional variables associated with relapse were duration of CR1, cytogenetic findings, and year of transplantation. In the multivariate analysis, hypodiploidy, t(4;11), and t(9;22) were separately found to be associated with an increased risk of relapse and therefore were grouped together for comparison with hyperdiploidy, other abnormal cytogenetic findings, and normal cytogenetic results. The multivariate analysis showed that all groups of cytogenetic abnormalities, including hyperdiploidy, were associated with a higher risk of relapse compared with normal cytogenetic findings. Among patients with CR2, CR3, or relapse at transplantation, those in whom CR1 had lasted 24 months or less (22 patients with CR2, none with CR3, and 20 with relapse) had a higher risk of relapse. Patients who underwent transplantation after 1992 had a higher risk of relapse. These patients also received significantly more (P < .0001) intensive chemotherapy (defined as at least one cycle of intensification or high-dose combination chemotherapy as part of the initial or relapse regimen) before transplantation.

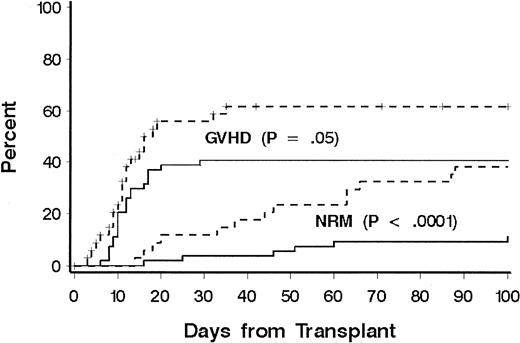

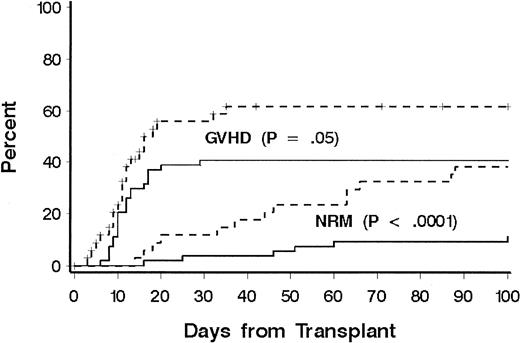

Thirty-one patients died of causes other than relapse (Table 2). Eighteen patients (60%) were receiving treatment for GVHD at the time of death, including 10 of 14 patients who died from infection. Three patients died of malignant astrocytoma at 4, 6, and 11 years, respectively, after transplantation; all had received cranial irradiation for prophylaxis or treatment for CNS leukemia during conventional chemotherapy for ALL. NRD rates according to phase of disease at transplantation were 20%, 22%, 60%, and 41%, respectively, for patients with CR1, CR2, CR3, and relapse, and disease phase was significantly associated with NRD in multivariate models (Table 3). Additional factors associated with NRD in the multivariate model were age at transplantation, immunophenotype, HLA matching, and donor-recipient sex matching. The risk of NRD was greater in patients 10 years or older, patients with a donor of the same sex, and patients with HLA-mismatched donors. Among older patients, both organ toxicity and grades III to IV GVHD contributed to the increase in risk of NRD (Figure 2). Only 13 patients had a T-cell or null-cell immunophenotype, and none died of causes other than relapse. To explain the association of sex matching, we examined whether sex-mismatched transplantations were associated with one sex or with GVHD and whether sex was associated with NRD or LFS, but no significant associations were found.

Cumulative incidence of NRD and GVHD according to patient age.

A comparison was made between patients younger than 10 years (solid lines) and patients aged 10 years or older (dotted lines). Significance was determined by log rank test.

Cumulative incidence of NRD and GVHD according to patient age.

A comparison was made between patients younger than 10 years (solid lines) and patients aged 10 years or older (dotted lines). Significance was determined by log rank test.

Because previous studies of patients with acute leukemia found an association between cell doses of at least 3.65 × 108marrow cells/kg and a lower risk of NRD among patients with remission, we analyzed all patients and those with remission at transplantation with respect to cell dose. We found that patients with remission who received at least 3.65 × 108 marrow cells/kg had a significant reduction in NRD compared with those who received less than 3.65 × 108 marrow cells/kg (17% versus 56%;P = .04), but marrow cell dose was not a significant factor in the entire group.

Engraftment

The median time to neutrophil engraftment after transplantation was 19 days. Three patients died before day 21 without having neutrophil recovery. Sustained engraftment was achieved in 84 of 85 patients who survived beyond day 21. One patient with CR2 at transplantation died of graft failure 66 days after receiving marrow from a donor mismatched for HLA-C and DRB1. The median time to platelet recovery was 21 days. Eighteen patients died before day 100, and 6 were alive on day 100 without platelet recovery.

GVHD

Grades II to IV acute GVHD occurred in 76 patients (overall incidence, 85%). In 43 patients (49%), grade III or IV GVHD developed. A lower incidence of grade III or IV GVHD was significantly associated with age less than 10 years (41% versus 62%;P = .05; Figure 2). There was a weak association with HLA match compared with HLA mismatch (43% versus 59%;P = .10) and overall risk of grades III or IV GVHD. The incidence of chronic GVHD could be evaluated in 62 patients who survived beyond day 80. Chronic extensive GVHD was observed in 29 patients (47%), whereas limited chronic GVHD was observed in 7 (11%). No factor was found to be significantly associated with the risk of chronic extensive GVHD, including donor-recipient HLA match (P = .23). Among the 28 long-term survivors, the median duration of immunosuppressive therapy was 1 year. Ten patients received immunosuppressive therapy for less than 1 year after transplantation, 10 patients for 1 year, and 8 patients for longer than 1 year (median, 2 years; range, 1.5 to > 5 years).

Discussion

An important advance in the treatment of ALL is identification of factors associated with a favorable or an unfavorable prognosis. Unfavorable prognostic factors at initial diagnosis were found to be age more than 10 years or less than 1 year, WBC count above 50 × 109/L, and the cytogenetic abnormalities t(4;11), t(9;22), and hypodiploidy.31-35 In contrast, age between 2 and 10 years, WBC count below 10 × 109/L, and hyperdiploid karyotype were associated with a favorable prognosis. Poor response to induction chemotherapy also was found to identify patients at high risk of relapse. Knowledge of prognostic factors has improved the ability to tailor modern treatment regimens, resulting in improvements in survival and late effects.

Among patients who experience relapse, the length of CR1 was an important prognostic factor for outcome after conventional reinduction chemotherapy. A CR1 duration of longer than 24 months has been associated with a relatively good outcome, and less than 20% of patients who develop relapse within 2 years of diagnosis survive when treated with conventional chemotherapy alone.36,37Comparisons between transplantation and conventional chemotherapy are difficult because unavoidable differences in patient populations result in selection bias.38 To address this problem, matched-pair analyses have been done for patients with CR2 treated with chemotherapy or HLA-identical marrow transplants from related donors.39 40 Particularly for patients with a short CR1 marrow transplantation resulted in significantly better LFS at 5 years compared with chemotherapy alone.

The aim of this study was to identify factors associated with outcomes of URD marrow transplantation for treatment of childhood ALL. Although we found that phase of disease was the strongest predictor of outcome, we also identified other factors as important prognostic variables: age and duration of CR1 were significantly associated with LFS. In addition, our results suggest that immunophenotype, cytogenetic abnormalities, and donor-recipient HLA and sex matching also may be important variables for predicting risk of relapse or NRD. The most favorable results were in younger patients and those with less advanced disease, whereas only a small proportion of patients with relapse at transplantation had long-term survival.

The improved survival in younger patients can be explained entirely by the lower risk of NRD, since there were no differences in risk of relapse among age groups. Older patients had a higher incidence of both severe GVHD and regimen-related complications after transplantation. Our results suggest that HLA matching and high cell dose might improve outcome in older patients because these factors were associated with a reduction in NRD. The beneficial effect of high marrow cell dose was observed in patients with remission, findings that are consistent with the results of a previous study that included adult patients with ALL and acute myeloid leukemia.10 Although HLA mismatching increased the risk of GVHD, there was also a trend toward a lower risk of relapse, suggesting that a graft-versus-leukemia effect compensated for the increase in NRD. Because HLA matching was defined by different methods of typing in use during the years in which this study was conducted, the HLA-matched group likely included patient-donor pairs with undetected allele mismatches at the class I or DQB1 loci.41 Thus, while this study indicates that a mismatch for one HLA-A, HLA-B, or DRB1 antigen does not affect outcome, the true effect of HLA matching may have been masked.

In some studies, factors such as age, WBC count, immunophenotype, cytogenetic abnormalities, and duration of CR1 were previously found to correlate with outcome after transplantation of marrow from HLA-identical siblings.36-40,42-44 The few studies that evaluated prognostic factors in patients with ALL who had URDs had insufficient numbers of patients or included adults.10,45,46 The current study represents the largest single-institution experience so far of a standard URD transplantation regimen for children with ALL. Our results indicate that remission duration is significantly associated with LFS, in the same way that it is a predictor of survival after chemotherapy given to treat a first relapse.39 40 The improvement in LFS in patients with a longer CR1 is explained by their lower risk of relapse after transplantation, a result consistent with the idea that shorter remission is a marker for increased disease aggression. Our results also suggest that T or null cell ALL may constitute a favorable risk group, however this observation must be tested in a group that includes more patients with these immunophenotypes.

We found that patients who underwent transplantation after 1992 had worse outcomes than those treated earlier. Although supportive care practices have improved over time, patients treated more recently also have received more intensive therapies before transplantation. Thus, as improved chemotherapy regimens become more successful in curing patients, those who develop relapse may have disease more resistant to treatment with both chemotherapy and marrow transplantation, and assessment of prognostic factors will become more important in predicting outcome after either type of therapy.

One concern regarding implementation of our findings may be the degree to which the donor-identification process may have resulted in inclusion of patients with more durable remissions, thereby producing selection bias. To determine whether selection bias affected the current study, we compared the study group with concurrently treated recipients of HLA-matched sibling grafts in our institution. We found no significant differences in duration of CR1 or time from diagnosis to transplantation arguing against bias in selection of patients for URD marrow transplantation. However, because we cannot exclude selection bias with respect to patients treated according to chemotherapy regimens, our results should not be used for comparison purposes; rather, they are intended to improve understanding of risk factors associated with outcome after URD transplantation.

Information about prognostic factors provided by the current study can be used to direct future strategies to improve outcome for children with ALL who undergo URD marrow transplantation. Because younger patients have a lower risk of NRD, efforts should be focused upon reducing the risk of relapse, which includes transplantation at earlier phases of ALL. For those with a short CR1 and consequent high risk of disease progression, a donor with a single HLA disparity should be considered if the alternative would involve a considerable delay to allow additional donor HLA testing. We found no apparent reduction in LFS in recipients of marrow from a donor mismatched for a single HLA-A, HLA-B, or DRB1 allele.

In contrast, older patients have a greater risk of GVHD and NRD. T-cell depletion has been used effectively to decrease the incidence of GVHD; however, comparative analyses of T-cell–depleted grafts and unmanipulated grafts found no improvement in survival.47 Alternative efforts to minimize GVHD and improve LFS in older patients might include the use of DNA-based HLA typing to optimize donor selection. Use of donors matched at the allele level for HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, DRB1, and DQB1 was shown to improve results in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia,41although the importance of allele-level matching in patients with acute leukemia has not been ascertained. Molecular HLA matching, however, will not be relevant for patients who have limited donor options. Of broader applicability are strategies to increase cell dose through the use of peripheral blood (PB) stem cells.48 Our finding of a favorable effect of cell dose on NRD is supported by results of previous studies including larger numbers of older patients.49,50 Thus far, studies of URD PB stem cells have found that the risk of acute or chronic GVHD is similar to that with marrow grafts.48 These results, together with findings of improved LFS after transplantation of PB stem cells from matched related donors, support further study of PB stem cell products for use in older patients.51

We thank Meg Bender and Chevonne Munnell for assistance in preparing the manuscript.

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants DK02431, CA-18029, CA-18221, and CA-47748.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Ann E. Woolfrey, Pediatric Transplantation, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, D5-280, 1100 Fairview Ave North, Seattle, WA 98109; e-mail: awoolfre@fhcrc.org.