Glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) are enzymes involved in the detoxification of several environmental mutagens, carcinogens, and anticancer drugs. GST polymorphisms resulting in decreased enzymatic activity have been associated with several types of solid tumors. We determined the prognostic significance of the deletion of 2 GST subfamilies genes, M1 and T1, in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Using polymerase chain reactions, we analyzed theGSTM1 and GSTT1 genotype in 106 patients with AML (median age, 60.5 years; range, 19-76 years). The relevance ofGSTM1 and GSTT1 homozygous deletions was studied with respect to patient characteristics, response to therapy, and survival. Homozygous deletions resulting in null genotypes at theGSTM1 and GSTT1 loci were detected in 45 (42%) and 30 (28%) patients, respectively. The double-null genotype was present in 19 patients (18%). GST deletions predicted poor response to chemotherapy (P = .04) and shorter survival (P = .04). The presence of at least one GST deletion proved to be an independent prognostic risk factor for response to induction treatment and overall survival in a multivariate analysis including age and karyotype (P = .02). GST genotyping was of particular prognostic value in the cytogenetically defined intermediate-risk group (P = .003). In conclusion, individuals with GSTM1 or GSTT1 deletions (or deletions of both) may have an enhanced resistance to chemotherapy and a shorter survival.

Introduction

Chemical carcinogens react with DNA after metabolic activation by hydrolysis, reduction, or oxidation. The results of this interaction are mutations and eventually the initiation of cancer. Glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) are a family of cytosolic enzymes contributing to the detoxification of activated carcinogens.1-3 Substrates for the GST enzymes are environmental pollutants, such as benzo(a)pyrene and other polyaromatic hydrocarbons, but also anticancer drugs, including alkylating agents, anthracyclines, and cyclophosphamide metabolites.1-3

Four major classes of GSTs have been described (α, μ, π, τ). Two members of these, GSTM1 and GSTT1, exhibit genetic polymorphism in their population distribution, with a large proportion of individuals presenting with homozygous deletion of the genes. This causes absence of the specific enzymatic activity.GSTM1 and GSTT1 deletions have been shown to be important risk factors for the development of solid tumors, including lung, larynx, and bladder cancer, particularly when associated with absence of other enzymes or prolonged exposure to carcinogens, like tobacco.2-4

Recently, some studies have addressed the role of GST polymorphisms in the development of hematologic malignancies. Few data were reported so far for adults with acute myeloid leukemia (AML),10-15 and, in particular, to our knowledge, there are only few reports on the relationship between GST genotypes, clinical outcome, and established indicators of prognosis in adult AML.

We examined the frequency of GSTM1 and GSTT1deletions in adults with AML and correlated the genotypic status to patient clinical and biologic characteristics. Finally, we investigated the impact of GST genotyping on response to induction therapy and overall survival of adult AML.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patient characteristics

Our retrospective analysis included 51 women and 55 men with AML (median age, 62 years; range, 19-75 years), with diagnosis made between February 1992 and March 2001.

The diagnosis of AML was established according to morphology and immunophenotype, following the French-American-British (FAB) classification criteria. Fifteen patients had a leukemia secondary to a previous malignancy. Karyotype was available for 77 patients; none of them had abnormalities of chromosomes 1p (location of GSTM1) or of chromosome 22q (location of GSTT1). Patients were treated according to current AML protocols of the Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche Maligne dell'Adulto (GIMEMA group), combining an anthracycline (doxorubicin or idarubicin or mitoxantrone), cytarabine, and etoposide for induction, followed by chemotherapy consolidation and, for eligible patients, autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplantation (EORTC-GIMEMA AML 10, 12, and 13). Eleven patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia were treated according to the GIMEMA-AIDA 0493 protocol (www.gimema.org). Toxic deaths were defined as all deaths occurring after start of treatment and before bone marrow evaluation on day +28 (n = 11). Complete remission (CR) or partial remission and resistance to induction treatment were assessed by bone marrow evaluation on day +28 in 95 patients (excluding 11 toxic deaths), according to standard National Cancer Institute criteria.16 Informed consent was obtained from all patients, according to institutional guidelines.

DNA extraction and amplification

Mononuclear cells (MNCs) were separated from the bone marrow of AML patients at the time of initial diagnosis, using Ficoll density centrifugation at 400g for 20 minutes. Cells were then washed 2 times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 400gand 4°C for 7 minutes, and DNA was extracted using DNAzol (Gibco BRL, Eggenstein, Germany), following the manufacturer's instructions. A multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique that detects homozygous deletions of GSTM1 and GSTT1 was used, including primers for the housekeeping gene BCL2 as internal control. PCR was carried out in a 50-μL mixture containing 100 ng gDNA, and a “master” mix of PCR buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 250 nM deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate, 1.25 U Taq polymerase (Taq Platinum; Gibco BRL) and 0.8 μM of the following primers: 5′-TTCCTTACTGGTCCTCACATCTC, 5′-TCACCGGATCATGGCCAGCA forGSTT1, 5′-GAACTCCCTGAAAAGCTAAAGC, 5′-GTTGGGCTCAAATATACGGTGG for GSTM1 and 5′-GCAATTCCGCATTTAATTCATGG-3′, 5′-GAAACAGGCCACGTAAAGCAAC-3′ for BCL2. Amplification consisted of 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 minute, annealing at 62°C for 1 minute, and extension at 72°C for 1 minute. This results in a fragment of 480 bp for GSTT1, 219 bp forGSTM1, and 154 bp for BCL2. The amplification efficiency of the internal control BCL2 was tested in preliminary experiments and proved to be similar to that ofGSTM1 and GSTT1 (data not shown). A positive and negative control, containing water instead of DNA, was included in all PCRs. PCR products were analyzed on a 2% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of the differences between groups was calculated using the Fisher exact test (2-sided). Crude odds ratios (ORs) were performed separately for GSTM1 andGSTT1 deletions and are given within 95% CIs. Age, sex, FAB subtype, history of previous cancer, and cytogenetics were included as covariables as were all genotypes and possible interactions. Cytogenetic risk groups were defined according to Grimwade et al17: favorable: t(8;21), t(15;17), inv(16); intermediate: normal, +8, +21, +22, del(7q), del(9q), abnormal 11q23, all other structural/numerical abnormalities without additional favorable or adverse cytogenetic changes; unfavorable: −5, −7, del(5q), abnormal 3q, complex karyotype. Multivariate regression models were performed to examine the relationship between the dependent variable (presence of GSTM1 or GSTT1 deletion) and potential predictor variables, both continuous and dichotomic, that is, age and karyotype. Event-free survival was defined as the time between initial diagnosis and relapse or death, whereas overall survival was the time between diagnosis and death. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier product-limit method. Differences in the survival curves were evaluated with the log-rank test. All computations were performed using the Stata 6.0 software (Stata, College Station, TX).

Results

Frequency of GST deletions and patient characteristics

The GSTM1 null genotype was detected in 45 AML patients (42.4%) and the GSTT1 null genotype in 30 patients (28%); 19 patients (17.9%) had a double-null genotype.

The GST genotype was correlated to patient characteristics by examining the GSTM1 and GSTT1 deletions separately (Table1). We grouped patients according to age, sex, history of previous cancer, FAB type, and cytogenetics. The effect of age was compared splitting the patients into 2 age groups (19-59 years, n = 48, and 60-75 years, n = 58). A higher frequency of GST deletions was found in patients over 60 years of age (Table 1). When compared to patients with a double-positive GST genotype, an association between the presence of any GST null genotype and age of 60 years and older was found (P = .006; OR, 3.2, 95% CI, 1.4-7). No association between sex and GST genotypes was found (Table1). Because GSTs are involved in detoxification of both natural and drug carcinogens, we analyzed the distribution of GST genotypes with respect to the history of previous cancer. No differences were observed comparing de novo leukemias versus leukemias secondary to other malignancies (Table 1). Furthermore, no differences were found when grouping patients according to FAB subtype, although it should be recognized that the numbers in each category might have been too small to detect significant effects (Table 1).

Patient characteristics and GST deletions (crude OR)

| . | (n) . | GSTM1−n (%) . | GSST1−n (%) . | GSTM1−/GSTT1−n (%) . | GSTM1+/GSTT1+n (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, n = 106 | ≥60 (58) | 32 (55.2) | 21 (36.2) | 15 (26.8) | 20 (34.5) |

| ≤59 (48) | 13 (27.1) | 9 (18.7) | 4 (8.3) | 30 (62.5) | |

| OR (95% CI) | 3.3 (1.5-7.5) | 2.5 (1-6) | 3.8 (1.2-12) | 0.3 (0.1-0.7) | |

| P | .005 | .05 | .02 | .006 | |

| Sex, n = 106 | Female (51) | 20 (39.2) | 11 (21.6) | 6 (11.8) | 26 (50.9) |

| Male (55) | 25 (45.4) | 19 (34.5) | 13 (23.6) | 24 (43.6) | |

| P | .8 | .2 | .1 | .6 | |

| Previous cancer, n = 106 | Yes (15) | 7 (46.7) | 4 (26.7) | 4 (26.7) | 8 (53.3) |

| No (91) | 38 (41.7) | 26 (28.6) | 15 (16.5) | 42 (46.1) | |

| P | .8 | 1 | .5 | 0.8 | |

| Karyotype, n = 77 | Normal (34) | 12 (35.3) | 10 (29.4) | 7 (20.6) | 19 (55.9) |

| Simple tran*(20) | 11 (55) | 6 (30) | 5 (25) | 11 (55) | |

| Complex (23) | 10 (43.5) | 5 (21.7) | 3 (13) | 8 (34.8) | |

| P | .3 | .8 | .6 | .2 | |

| Favorable (19) | 11 (57.9) | 6 (31.6) | 5 (26.3) | 7 (36.8) | |

| Intermediate (48) | 18 (37.5) | 13 (27.1) | 10 (20.8) | 27 (56.2) | |

| Unfavorable (10) | 4 (40) | 2 (20) | 0 (0) | 4 (40) | |

| P | .3 | .8 | .2 | .2 | |

| FAB, n = 96 | M0-M1 (9) | 4 (44.4) | 2 (22.2) | 2 (22.2) | 5 (55.5) |

| M2 (40) | 16 (40) | 14 (35) | 8 (20) | 17 (42.5) | |

| M3 (11) | 6 (54.5) | 2 (18.2) | 2 (18.2) | 5 (45.4) | |

| M4 (20) | 7 (35) | 3 (15) | 2 (10) | 12 (10) | |

| M5 (8) | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) | 2 (25) | 2 (25) | |

| M6 (8) | 2 (25) | 2 (25) | 1 (12.5) | 5 (62.5) | |

| P | .6 | .6 | .7 | .7 |

| . | (n) . | GSTM1−n (%) . | GSST1−n (%) . | GSTM1−/GSTT1−n (%) . | GSTM1+/GSTT1+n (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, n = 106 | ≥60 (58) | 32 (55.2) | 21 (36.2) | 15 (26.8) | 20 (34.5) |

| ≤59 (48) | 13 (27.1) | 9 (18.7) | 4 (8.3) | 30 (62.5) | |

| OR (95% CI) | 3.3 (1.5-7.5) | 2.5 (1-6) | 3.8 (1.2-12) | 0.3 (0.1-0.7) | |

| P | .005 | .05 | .02 | .006 | |

| Sex, n = 106 | Female (51) | 20 (39.2) | 11 (21.6) | 6 (11.8) | 26 (50.9) |

| Male (55) | 25 (45.4) | 19 (34.5) | 13 (23.6) | 24 (43.6) | |

| P | .8 | .2 | .1 | .6 | |

| Previous cancer, n = 106 | Yes (15) | 7 (46.7) | 4 (26.7) | 4 (26.7) | 8 (53.3) |

| No (91) | 38 (41.7) | 26 (28.6) | 15 (16.5) | 42 (46.1) | |

| P | .8 | 1 | .5 | 0.8 | |

| Karyotype, n = 77 | Normal (34) | 12 (35.3) | 10 (29.4) | 7 (20.6) | 19 (55.9) |

| Simple tran*(20) | 11 (55) | 6 (30) | 5 (25) | 11 (55) | |

| Complex (23) | 10 (43.5) | 5 (21.7) | 3 (13) | 8 (34.8) | |

| P | .3 | .8 | .6 | .2 | |

| Favorable (19) | 11 (57.9) | 6 (31.6) | 5 (26.3) | 7 (36.8) | |

| Intermediate (48) | 18 (37.5) | 13 (27.1) | 10 (20.8) | 27 (56.2) | |

| Unfavorable (10) | 4 (40) | 2 (20) | 0 (0) | 4 (40) | |

| P | .3 | .8 | .2 | .2 | |

| FAB, n = 96 | M0-M1 (9) | 4 (44.4) | 2 (22.2) | 2 (22.2) | 5 (55.5) |

| M2 (40) | 16 (40) | 14 (35) | 8 (20) | 17 (42.5) | |

| M3 (11) | 6 (54.5) | 2 (18.2) | 2 (18.2) | 5 (45.4) | |

| M4 (20) | 7 (35) | 3 (15) | 2 (10) | 12 (10) | |

| M5 (8) | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) | 2 (25) | 2 (25) | |

| M6 (8) | 2 (25) | 2 (25) | 1 (12.5) | 5 (62.5) | |

| P | .6 | .6 | .7 | .7 |

Statistical significance obtained using the Fisher exact test (2-sided). Cytogenetic risk groups were defined according to Grimwade et al17 (see “Patients, materials, and methods”).

Simple balanced translocations.

Cytogenetic data were available for 77 patients. Thirty-four patients had a normal karyotype, 20 had a simple balanced translocation, and 23 patients had a complex karyotype. This corresponds to 19 patients with prognostically favorable, 48 with intermediate, and 10 with unfavorable cytogenetics, according to Grimwade et al.17 No differences in the frequency of GST deletions were found when comparing the different groups (Table 1).

Prognostic value of GSTM1 and GSTT1deletions

The role of GSTs in the detoxification of chemotherapy agents prompted us to examine the relationship between response to chemotherapy and GST genotype. When considering patients who died of toxic complications after initiation of chemotherapy, but before response assessment at day 28 (n = 11), no associations between GST deletions and toxic deaths were found, although the number of patients might have been too low to detect differences.

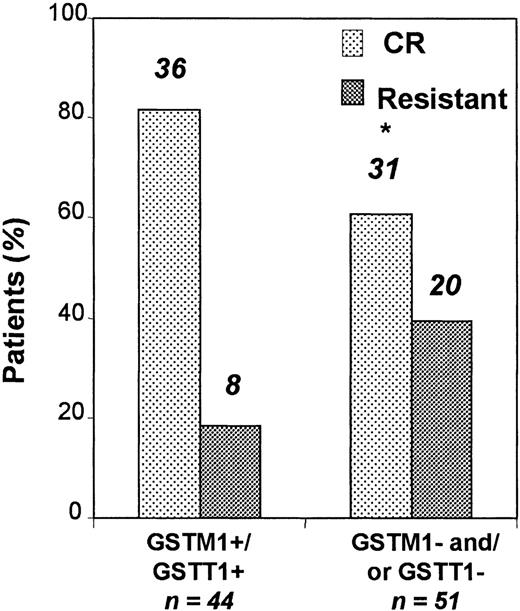

Ninety-five patients were evaluable for the response to induction treatment analysis. Following induction therapy, 67 patients achieved CR, whereas 28 patients were resistant. When compared to patients withGSTM1 or GSTT1 deletions, patients with an undeleted genotype had a significantly better response to induction therapy (Figure 1). Thirty-six of 44 (81.8%) patients with undeleted genotype and 31 of 51 (60.8%) of those with GSTM1 or GSTT1 deletions achieved CR (OR for risk of not achieving CR = 2.9; 95% CI, 1.2-7.5;P = .04). The multivariate analysis showed that this risk was independent of age and karyotype (P = .02; Table2).

Patients with an undeleted GST genotype responded significantly better to induction therapy.

Thirty-six (81.8%) of 44 patients with undeleted genotype and 31 (60.8%) of 51 of those with GSTM1 or GSTT1deletions (or both deletions) achieved CR (P = .04). Early deaths (n = 11) were excluded from this analysis. Asterisk indicates statistically significant.

Patients with an undeleted GST genotype responded significantly better to induction therapy.

Thirty-six (81.8%) of 44 patients with undeleted genotype and 31 (60.8%) of 51 of those with GSTM1 or GSTT1deletions (or both deletions) achieved CR (P = .04). Early deaths (n = 11) were excluded from this analysis. Asterisk indicates statistically significant.

Multivariate analysis

| . | . | Resistance to induction . | Overall survival . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR . | 95% CI . | P . | HR . | 95% CI . | P . | ||

| GSTM1/GSTT1 | Any deletion vs normal | 4.7 | 1.2-18.1 | .02 | 2.4 | 1.2-4.9 | .02 |

| Age, y | ≥60 vs ≤59 | .1 | 3 | 1.5-6.3 | .002 | ||

| Karyotype | Favorable vs intermediate vs unfavorable | 5 | 1.6-15.8 | .005 | 2.5 | 1.4-4.4 | .001 |

| All variables | .001 | .0001 | |||||

| . | . | Resistance to induction . | Overall survival . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR . | 95% CI . | P . | HR . | 95% CI . | P . | ||

| GSTM1/GSTT1 | Any deletion vs normal | 4.7 | 1.2-18.1 | .02 | 2.4 | 1.2-4.9 | .02 |

| Age, y | ≥60 vs ≤59 | .1 | 3 | 1.5-6.3 | .002 | ||

| Karyotype | Favorable vs intermediate vs unfavorable | 5 | 1.6-15.8 | .005 | 2.5 | 1.4-4.4 | .001 |

| All variables | .001 | .0001 | |||||

Cytogenetic risk groups were defined according to Grimwade et al17 (see “Patients, materials, and methods”).

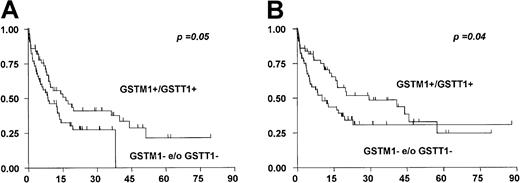

The higher rate of CRs in patients with both an undeletedGSTM1 and GSTT1 genotype translated in a significantly longer event-free and overall survival as compared with patients with single or combined deletions (median event-free survival, 11.2 and 7.5 months, P = .05, and median overall survival, 15 and 8 months, respectively, P = .04; Figure2).

GST deletions are of negative prognostic value for overall survival.

Patients with any GST deletions (n = 56) had a significantly shorter event-free (A) and overall survival (B) than those with undeletedGSTM1 and GSTT1 genes (n = 50).

GST deletions are of negative prognostic value for overall survival.

Patients with any GST deletions (n = 56) had a significantly shorter event-free (A) and overall survival (B) than those with undeletedGSTM1 and GSTT1 genes (n = 50).

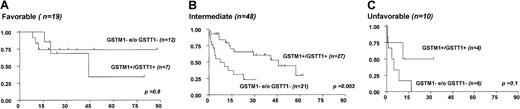

We next analyzed whether the presence of at least one GST null genotype was an independent prognostic factor. In the multivariate analysis using the Cox regression model, we included age and cytogenetics as well established prognostic factors (Table 2). In this analysis, the presence of at least one GST deletion proved to be a poor prognostic factor for survival (P = .01, Table 2). GST genotyping could discriminate between favorable and unfavorable prognosis in patients with intermediate-risk karyotype (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.9 for at least one GST null genotype, P = .003), whereas no impact of GST genotyping on prognosis became evident in patients with either favorable or unfavorable karyotype17 (Figure3).

The presence of single or double GST deletions in patients with intermediate-risk karyotype is associated with poor outcome.

Patients were grouped according to cytogenetics and their overall survival curves according to GST− status are shown.GSTM1− and GSTT1−indicate patients with GSTM1 and GSTT1 deletions, whereas GSTM1+/GSTT1+ indicates patients with undeleted GST genotype.

The presence of single or double GST deletions in patients with intermediate-risk karyotype is associated with poor outcome.

Patients were grouped according to cytogenetics and their overall survival curves according to GST− status are shown.GSTM1− and GSTT1−indicate patients with GSTM1 and GSTT1 deletions, whereas GSTM1+/GSTT1+ indicates patients with undeleted GST genotype.

Discussion

Environmental pollutants and anticancer drugs, including alkylating agents, anthracyclines, and cyclophosphamide metabolites, are detoxified by enzymes that catalyze reactions as glucuronidation, sulfonation, acetylation, methylation, and conjugation with glutathione or amino acids, following activation.1-3

We found an increased frequency of GSTM1 null genotypes in patients with AML over 60 years of age. Prolonged exposition of hematopoietic progenitor cells to toxic agents in combination with a reduced capability of detoxification might contribute to the pathogenesis of AML in the elderly. Because the incidence of AML evolving after cytotoxic treatment for malignant disease increases with age, one might also expect an association between GST null genotypes and the risk for therapy-related leukemia.18 In our study group, no differences between de novo and secondary leukemias were observed.

Leukemias of the elderly and therapy-related leukemias often show a higher frequency of prognostically unfavorable cytogenetic changes.19,20 Rollinson et al10 found an increased frequency of GSTT1 null genotypes in patients with balanced translocations, whereas Crump et al14 reported an association between GSTT1 gene deletion and trisomy 8, as well as between GSTM1 gene deletion and trisomies other than +8 and inv(16). However, we could not find any association between karyotype and GST genotypes in the present series. Further studies on larger series of patients extensively characterized at the karyotypic level are probably needed to better investigate possible associations between GST genotype and cytogenetic abnormalities in AML.

In the present study, AML patients with deletions of GSTM1or GSTT1 or both had a lower probability to achieve CR on induction therapy as compared to patients with intact GST genes. The reasons underlying this finding are unclear. The lack of detoxification of electrophilic, DNA-damaging agents may contribute to the accumulation of genetic changes in the process of leukemogenesis. In this line, the absence of GST enzymes might simply reflect a biologically distinct, more aggressive disease. Although the available karyotypic results suggested absence of relevant associations between cytogenetic and GST genotypic status, we have no data on more subtle genetic changes including point mutations in oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes (ie, RAS, p53) and other karyotypically silent alterations such as FLT3 tandem duplication.19 20 Possible association of GST genotypes with molecular genetic alterations might represent an interesting topic for future investigation.

An alternative mechanism to explain the impact of GST genotypes on outcome results from the putative role of these enzymes in the metabolism of several cytotoxic drugs, such as anthracyclines, used in induction chemotherapy for patients with AML. GSTs contribute to detoxification either by direct conjugation of the drug with glutathione, increasing its secretion via bile and urine, or by neutralization of reactive compounds induced by the cytotoxic drug.1 This detoxification can protect cells from the injuries of chemotherapy. Expression of GST enzymes has been linked to in vitro and in vivo chemoresistance of tumor and leukemic cells.21,22 One might expect that a GST deficiency caused by the null genotype results in better response to chemotherapy. In this line, Stanulla et al23 showed a reduced risk of relapse in childhood B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) patients having GSTM1 null or GSTT1 null genotype, whereas in the study of Chen et al,6 no impact of GST genotypes was seen on patient response to therapy and outcome. A study on GST genotypes and outcome in childhood AML was recently published, where the authors described a worse prognosis for GSTT1 null individuals, largely due to an increase of toxic deaths.24We found a lower chemotherapy response rate and, consequently, a worse outcome in adults with AML and at least one GST null genotype. In keeping with our findings, the combined GST null genotype was associated with reduced responsiveness to chemotherapy, shorter progression-free interval, and poorer survival in patients with ovarian cancer.25

The deficiency of GST enzymes may cause higher levels of glutathione (GSH) because of reduced consumption of GSH in GST-catalyzed reactions. Accordingly, in addition to its role in detoxification, intracellular glutathione has also been implicated in the control of cell proliferation and apoptosis. By increasing glutathione levels, proliferation of T lymphocytes could be enhanced and apoptosis inhibited.26,27 This concept is supported by data from a recent report in which high intracellular GSH levels in lymphoid blasts were correlated with greater risk of relapse and reduced overall survival in childhood ALL.21 Interestingly, in the same study there was no relationship between glutathione levels and in vitro drug sensitivity.21

The prognostic importance of the GST genotype was supported by our multivariate analysis, where the GST genotype was an independent predictor for overall survival. In particular, GST genotyping could discriminate between favorable and unfavorable prognosis in the cytogenetically defined intermediate-risk group, which contains the majority of AML patients. Therefore, GST genotyping might complement diagnostic cytogenetics, thereby providing a more accurate risk assessment, which may ultimately permit a more refined treatment approach.

Supported by grants from Ministero dell' Universita' e della Ricerca Scientifica e Tecnologica (MURST) and Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Maria Teresa Voso, Istituto di Ematologia, Universita' Cattolica S. Cuore, L go A. Gemelli, 100168 Rome, Italy; e-mail: mtvoso@rm.unicatt.it.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal