We have identified 2 PROS1 missense mutations in the exon that encodes the vitamin K–dependent Gla domain of protein S (Gly11Asp and Thr37Met) in kindred with phenotypic protein S deficiency and thrombosis. In studies using recombinant proteins, substitution of Gly11Asp did not affect production of protein S but resulted in 15.2-fold reduced protein S activity in a factor Va inactivation assay. Substitution of Thr37Met reduced expression by 33.2% (P < .001) and activity by 3.6-fold. The Gly11Asp variant had 5.4-fold reduced affinity for anionic phospholipid vesicles (P < .0001) and decreased affinity for an antibody specific for the Ca2+-dependent conformation of the protein S Gla domain (HPS21). Examination of a molecular model suggested that this could be due to repositioning of Gla29. In contrast, the Thr37Met variant had only a modest 1.5-fold (P < .001), reduced affinities for phospholipid and HPS21. This mutation seems to disrupt the aromatic stack region. The proposita was a compound heterozygote with free protein S antigen levels just below the lower limit of the normal range, and this is now attributed to the partial expression defect of the Thr37Met mutation. The activity levels were strongly reduced to 15% of normal, probably reflecting the functional deficit of both protein S variants. Her son (who was heterozygous only for Thr37Met) had borderline levels of protein S antigen and activity, reflecting the partial secretion and functional defect associated with this mutation. This first characterization of natural protein S Gla-domain variants highlights the importance of the high affinity protein S–phospholipid interaction for its anticoagulant role.

Introduction

Protein S is a plasma glycoprotein that plays an important role in the protein C anticoagulant pathway by acting as a cofactor to activated protein C (APC) in the specific proteolytic inactivation of factors Va and VIIIa, reviewed in Simmonds and Lane.1 In healthy individuals, ∼60% of circulating protein S is found in complex with C4b binding protein, and only free protein S has APC cofactor activity. The physiological requirement for protein S is clearly demonstrated by the clinical manifestations of purpura fulminans in infants who lack detectable protein S at birth.2 Heterozygous deficiency of protein S is found in 1% to 2% of consecutive patients with deep vein thrombosis3 and has been classified into 3 subtypes. Type I (total and free protein S below the lower limit of a normal range) and type III (normal total protein S, but reduced free protein S levels) deficiencies are now commonly considered to be quantitative.4 Type II deficiency is qualitative and is characterized by reduced activity in a specific functional assay.

Mature protein S has a modular structure and consists of a vitamin K–dependent Gla domain that includes an aromatic stack region (residues 1 to 46), a region sensitive to cleavage by thrombin (residues 47 to 75), 4 domains homologous to epidermal growth factor (EGF-like domains, residues 76 to 242), and a region homologous to sex hormone binding globulin (residues 243 to 635). Inherited quantitative (type I and III) protein S deficiency is frequently caused by mutations within the gene for protein S, PROS1.4,5However, qualitative (type II) protein S deficiency is rarely reported and only a handful of PROS1 defects have been described.4 Only one of these, Lys9Glu, is located in the Gla domain of protein S, but its function has not been investigated.6 Here, we describe a kindred presenting with type II protein S deficiency caused by 2 mutations. Both mutations were present on separate alleles, in the exon that encodes the Gla domain of protein S, and experiments with recombinant proteins showed that each mutation resulted in a variant protein that was functionally defective due to aberrant Ca2+-induced phospholipid binding.

Patients, materials, and methods

Subjects, phenotypic, and clinical data

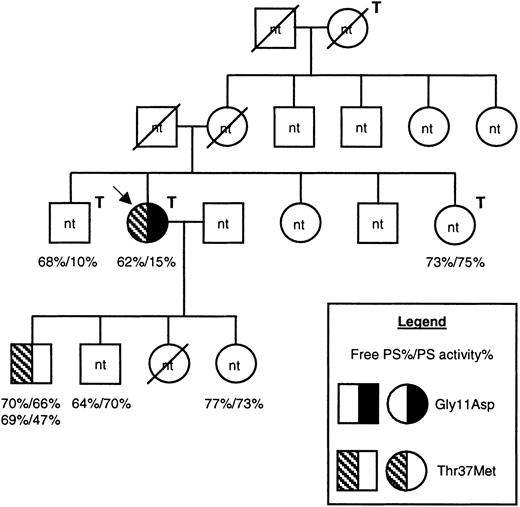

The proposita was a 61-year-old woman who had experienced 3 episodes of confirmed deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and multiple episodes of superficial venous thrombosis. The first episode of DVT was of the right leg at the age of 23 years in the postpartum stage of her second pregnancy. The second episode was a proximal DVT at the age of 58 years while receiving hormone replacement therapy. The third episode was a proximal DVT of the left leg without a known triggering factor at the age of 61 years. The proposita also had a family history of venous thrombosis (Figure 1). Free protein S antigen and protein S activity levels were assessed in several family members using plasma assays (Diagnostica Stago, Taverny, France). For both assays the normal range was 65% to 130%. In the proposita, free protein S antigen was low/borderline (62%), and protein S activity was substantially reduced (15%). Her son had no clinical history of thrombosis, and his protein S levels were measured on 2 separate occasions due to borderline levels of free protein S antigen (69%/70%) and low/borderline protein S activity (47%/66%). DNA samples were available only for these 2 individuals. The factor V Leiden mutation (Arg506Gln) was not present in the proposita. The study was performed according to the rules of the Ethics Committee of Hotel Dieu, Paris, and all participants gave informed written consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Pedigree of the family under investigation.

Males are shown as squares, females as circles, and deceased family members are crossed through. The proposita is indicated with an arrow, and family members who had experienced venous thrombosis are indicated with a T above and to the right of the symbol. Information regarding protein S levels is shown for all 6 family members for whom it was available, as indicated in the legend. For one individual, protein S levels were assessed on 2 separate occasions. DNA was available only from 2 family members. The presence of the Gly11Asp and Thr37Met mutations are indicated by a left-hand half-filled symbol and by a right-hand filled symbol, respectively (see legend). nt indicates family members for whom the genetic status was not tested; PS, protein S.

Pedigree of the family under investigation.

Males are shown as squares, females as circles, and deceased family members are crossed through. The proposita is indicated with an arrow, and family members who had experienced venous thrombosis are indicated with a T above and to the right of the symbol. Information regarding protein S levels is shown for all 6 family members for whom it was available, as indicated in the legend. For one individual, protein S levels were assessed on 2 separate occasions. DNA was available only from 2 family members. The presence of the Gly11Asp and Thr37Met mutations are indicated by a left-hand half-filled symbol and by a right-hand filled symbol, respectively (see legend). nt indicates family members for whom the genetic status was not tested; PS, protein S.

Identification and allelic distribution ofPROS1 mutations

DNA extraction from EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) anticoagulated whole blood was performed using the QIAamp DNA blood kit (QIAgen, Valencia, CA). Each exon and intron/exon boundary ofPROS1 was polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–amplified and sequenced as described previously.7 The allelic distribution of mutations was determined using a PCR-cloning strategy and TOPO TA cloning technology (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Exon 2 was PCR-amplified and 1 μL of the purified PCR product ligated into pCRII-TOPO and transformed into TOP10 One Shot Competent Cells according to the manufacturer's instructions. Ten of the resulting colonies were sequenced as described above.

Vector construction, mutagenesis, and transient expression experiments

Vector construction, mutagenesis, and transient expression of wild-type and variant protein S was performed essentially as previously described.7 Briefly, all vectors were based on a protein S cDNA cloned into pcDNA6 (Invitrogen) that was altered to have an exact match to the Kozak consensus sequence (A in position −3 and G at position +4, relative to the ATG initiation codon). Mutagenesis was performed using the Quickchange Site Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), using primers France 1A/1B and France 2A/2B to construct Gly11Asp and Thr37Met, respectively (Table1). Vectors were transfected into COS-1 cells using 3.5 μL Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), 2.0 μg of each protein S construct and 1.0 μg SEAP-control vector (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The SEAP-control vector encodes a secreted form of alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) and served as a control for transfection efficiency. Culture medium was collected and analyzed 72 hours after transfection. Protein S levels were assessed with an in-house ELISA,7 and the levels of SEAP were assessed using a chemiluminescent assay (Clontech), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Primers used for site-directed mutagenesis of the protein S cDNA

| Primers . | Sequence (5′ to 3′) . | Position* (5′ to 3′) . |

|---|---|---|

| France 1A | GAAACCAAACAGGATAATCTTGAAAG | 288 to 313 |

| France 1B | CTTTCAAGATTATCCTGTTTGGTTTC | 313 to 288 |

| France 2A | ATGACCCGGAAATGGATTATTTTTA | 368 to 391 |

| France 2B | TAAAAATAATCCATTTCCGGGTCAT | 391 to 368 |

| Primers . | Sequence (5′ to 3′) . | Position* (5′ to 3′) . |

|---|---|---|

| France 1A | GAAACCAAACAGGATAATCTTGAAAG | 288 to 313 |

| France 1B | CTTTCAAGATTATCCTGTTTGGTTTC | 313 to 288 |

| France 2A | ATGACCCGGAAATGGATTATTTTTA | 368 to 391 |

| France 2B | TAAAAATAATCCATTTCCGGGTCAT | 391 to 368 |

The mutated base is underlined.

Relative to protein S cDNA.44

Stable expression of protein S

Wild-type and variant protein S were stably expressed in Human Embryo Kidney (HEK) 293 cells (European Collection of Cell Cultures, Salisbury, United Kingdom). Complete growth medium for these cells was Eagle minimum essential medium (EMEM, Sigma, Poole, United Kingdom), supplemented with 1x MEM nonessential amino acid solution (Sigma), 2 mM l-glutamine (Sigma), 20 μg/mL vitamin K1 (Konakion, Roche, Lewes, United Kingdom), 10% (vol/vol) fetal calf serum (Imperial Laboratories, Andover, United Kingdom), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin sulfate (Sigma).

Stable transfection was performed by standard techniques using 2 μg DNA of each protein S construct and 10 μL Lipofectin (Invitrogen) reagent, according to the manufacturer's protocol. At 72 hours after transfection, the cells were transferred into a 100-mm dish and maintained in complete growth medium containing 5 μg/mL blasticidin (Invitrogen). Blasticidin resistant cells were grown to confluence. Protein production for functional studies was performed in 175-cm2 flasks. When the cells were confluent, complete medium was discarded, cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and replaced with Opti-MEM I with Glutamax (Invitrogen) supplemented with 20 μg/mL vitamin K1, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin sulfate, and 5 μg/mL blasticidin. After 5 days, cell culture supernatants were harvested, centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10 minutes, and filter sterilized. The levels of protein S present in conditioned medium were assessed by in-house ELISA and varied between 7.8 and 16.3 μg/mL. Aliquots of conditioned medium were subsequently dialyzed against 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 140 mM NaCl, and 3 mM CaCl2, and the ELISA repeated to confirm protein S levels. Dialyzed medium was stored in aliquots at −70°C.

Proteins and phospholipids

Purified human plasma proteins (protein S, APC, factor Xa, and prothrombin) were obtained from Enzyme Research Laboratories (South Bend, IN). Factor Va was obtained from Haematologic Technologies (Essex Junction, VT). Phospholipids were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL) and were provided as premixed dioleoyl-phosphatidylethanolamine/dioleoyl-phosphatidylcholine/dioleoyl-phosphatidylserine (PE/PC/PS, 40:40:20) and PC/PS (80:20) in chloroform. The chloroform was evaporated under nitrogen vapor, and the lipids were resuspended in ice-cold sterile water then mixed vigorously for 1 hour with shaking at 4°C. The resuspended vesicles were sonicated at 20 kHz for 5 minutes and stored for short periods at 4°C.

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as described previously.7 Briefly, 30 ng protein S was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) in a 4% to 20% polyacrylamide Tris-HCl gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Proteins transferred to Hybond-P (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) were detected using an anti–human protein S peroxidase-conjugated antibody (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection reagents (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Factor Va inactivation assay

Dialyzed recombinant protein S was diluted in buffer A (40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 140 mM NaCl, 0.2% [wt/vol] NaN3, 3 mM CaCl2, 0.3% [wt/vol] bovine serum albumin [BSA]) to provide a range of final recombinant protein S concentrations (0 to 20 nM) and was incubated with 0.1 nM APC, 3 nM factor Va, and 25 μM phospholipid vesicles for 2 minutes at 37°C in buffer A. Following incubation, 2 μL of this reaction was transferred to a separate tube containing 72 pM factor Xa, 0.5 μM prothrombin, and 25 μM phospholipid vesicles in buffer A at 37°C. After 3 minutes' incubation, the reaction was stopped with 3 μL of 0.5 M EDTA. The entire reaction was then mixed with 100 μL 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 130 mM NaCl, 0.075 KIU/mL Trasylol in a microtiter plate and incubated at 37°C for 10 minutes. The chromogenic substrate S2238 (Chromogenix Instrumentation Laboratories, Milano, Italy) was then added to a final concentration of 0.444 mM and incubated at 37°C for 5 minutes. The reaction was stopped with 10% acetic acid and the absorbance was read at 405 nm. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Phospholipid binding assays

The binding of protein S to anionic phospholipid vesicles was assessed using a microtiter-plate assay, adapted from van Wijnen et al.8 The washing steps were performed using buffer A. Phospholipid vesicles were coated onto the wells of microtiter plates at 25 μg/mL in 50 mM Na2CO3 (pH 9.6), overnight at 4°C. The plates were washed 3 times and blocked for 1 hour at room temperature with 315 μL buffer A supplemented with BSA to a final concentration of 3% (wt/vol). The plates were again washed 3 times, and protein S at a range of concentrations (0 to 26 nM) in buffer A was added and incubated for 2 hours at 37°C. After the plates were washed 3 times, 100 μL of rabbit anti–human protein S peroxidase-conjugated antibody diluted 1:2500 in buffer A was added to the wells and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Plates were washed 3 times and 100 μL peroxidase substrate, O-phenylenediamine (OPD; Dako) at 666 μg/mL in 33.3 mM citric acid, 66.7 mM Na2HPO4 (pH5.0), and 0.0002% H2O2 was added to each well and incubated at room temperature, in the dark, for 10 minutes. The reaction was stopped by addition of 75 μL 1.4 M H2SO4 and the absorbance at 492 nm was assessed. The binding of wild-type protein S to the phospholipid vesicles was also assessed in buffer A, where the CaCl2 was replaced with 5 mM EDTA. A further test of specificity was performed by adding increasing amounts of purified prothrombin, added as a competitor in the presence of 2.7 nM protein S. Minimal influence on protein S binding was observed up to equimolar amounts of prothrombin and protein S, after which prothrombin increasingly inhibited protein S binding to the phospholipid (50% at a 100-fold molar excess), as expected. All experiments were performed in triplicate. For each set of data, the Kd appand capacityapp were calculated using Enzfitter 2.0 software (Biosoft, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Saturation curves were fitted using a one-site ligand-binding model. The binding of 10 nM protein S to phospholipid vesicles at various concentrations of Ca2+ ions was also investigated. Here, several variations on buffer A were prepared containing either 0, 1, 2, 3, or 5 mM CaCl2, and the experiment was carried out as before, except that all reagents and washing steps for a particular well were performed using buffer A with the appropriate CaCl2concentration.

Antibody binding assays

The binding of recombinant protein S to different monoclonal antibodies (kind gifts from Prof Björn Dahlbäck, University of Lund, Malmö, Sweden) was assessed. HPS21 is specific for the Ca2+-dependent conformation of protein S Gla domain, and HPS54 is specific for the Ca2+-dependent conformation of the first EGF-like domain of protein S. Each of these antibodies was coated onto the wells of microtiter plates at 10 μg/mL in 50 mM Na2CO3 (pH 9.6), overnight at 4°C and blocked with casein. Dialyzed protein S at a range of concentrations (0 to 20 nM) in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 nM NaCl, 0.1% (wt/vol) NaN3, 3 mM CaCl2, 1% (wt/vol) casein, 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween 20 were added to the wells and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Plates were washed 4 times with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM CaCl2, and 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 and bound protein S was detected with a rabbit anti–human protein S peroxidase-conjugated antibody, as before.

Results

The coding regions and intron/exon boundaries of PROS1were amplified and sequenced in the symptomatic proposita (Figure 1). This revealed the presence of 2 heterozygous gene defects, both in exon 2 of PROS1 that encodes the Gla domain of the mature protein (data not shown). The mutations were 301 G to A and 380 C to T (numbering according to Schmidel et al5), and these were predicted to result in the amino acid substitutions Gly11Asp and Thr37Met. Using a PCR cloning strategy, the mutations were found to reside on different alleles. No other sequence abnormality was found. Analysis of exon 2 of PROS1 in a son of the proposita showed that he was heterozygous for the Thr37Met mutation but was normal at Gly11 (Figure 1 and data not shown).

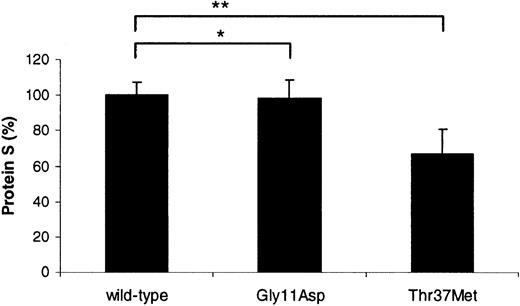

Transient transfection experiments in COS-1 cells were performed in order to assess whether either of the identified mutations influenced the ability of the cells to produce and secrete protein S (Figure2). Protein S bearing the Gly11Asp mutation was secreted at an equivalent level to the wild type (98.4% ± 9.9% compared to 100% ± 7.1%; P = .62). In contrast, the expression level of protein S with Thr37Met was reduced by ∼33% (66.9% ± 14.0% compared to 100% ± 7.1%;P < .0001). This indicated that the latter mutation was associated with a production defect, providing an explanation for the borderline levels of free protein S antigen observed in the son of the proposita. Recent findings from our laboratory indicate that the production defect is likely to be due to impaired secretion,7 although it cannot be ruled out that the reduced levels observed were due to defective transcription and/or translation.

Relative transient expression levels of recombinant wild-type and variant protein S in COS-1 cells.

Mean, relative concentration of protein S expressed after correction for transfection efficiency. A value of 100% was assigned to wild-type protein S. Each experiment was performed at least 3 times in duplicate. Unpaired t test was used to compare the levels between wild-type protein S and the variants; *P = .62; **P < .0001.

Relative transient expression levels of recombinant wild-type and variant protein S in COS-1 cells.

Mean, relative concentration of protein S expressed after correction for transfection efficiency. A value of 100% was assigned to wild-type protein S. Each experiment was performed at least 3 times in duplicate. Unpaired t test was used to compare the levels between wild-type protein S and the variants; *P = .62; **P < .0001.

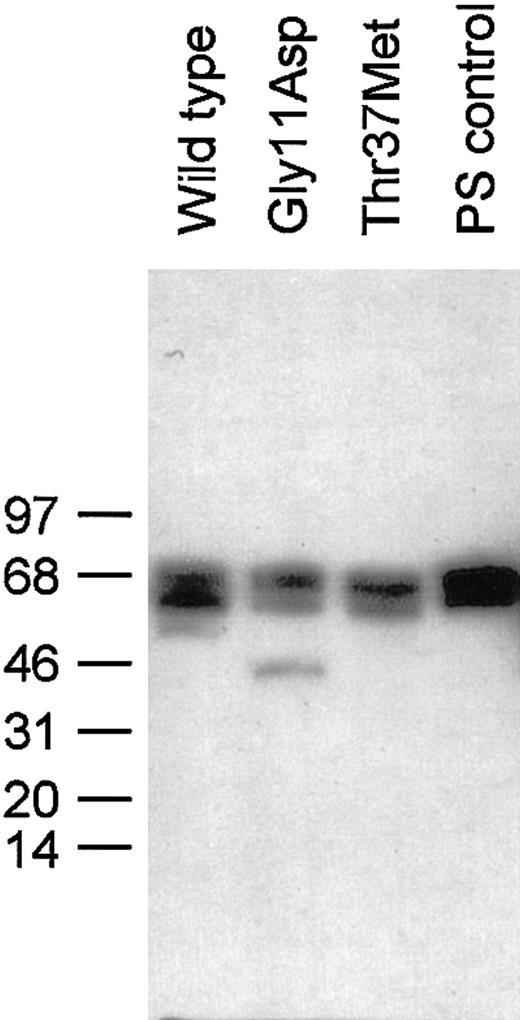

In order to investigate whether these mutations in PROS1caused any functional deficit in protein S, wild-type and variant protein S was stably expressed in HEK293 cells. Each recombinant human protein S and commercially available protein S purified from human plasma appeared as doublets following reducing SDS-PAGE and Western blot (Figure 3), as previously described.9 There was an additional minor band for Gly11Asp at ∼46 kDa, the precise nature of which is not known. As it was estimated to be less than 5% of the total protein S for this sample, it was not considered to be problematic for functional analysis.

Western blotting of wild-type protein S and variants expressed in HEK293 cells.

SDS-PAGE of 30 ng protein S under reducing conditions and immunoblotting with a polyclonal protein S antibody were performed as described in the text. The positions to which protein size markers migrated are indicated to the left, along with their molecular weight in kDa.

Western blotting of wild-type protein S and variants expressed in HEK293 cells.

SDS-PAGE of 30 ng protein S under reducing conditions and immunoblotting with a polyclonal protein S antibody were performed as described in the text. The positions to which protein size markers migrated are indicated to the left, along with their molecular weight in kDa.

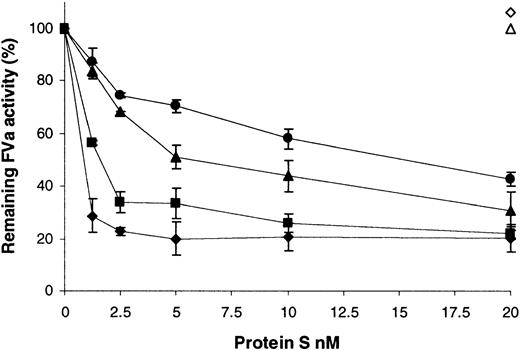

A factor Va inactivation assay was employed to assess the ability of the variants to act as a cofactor to APC (Figure4). Under these conditions and short incubation periods, 0.1 nM APC did not inactivate any factor Va in the absence of protein S (Figure 4, compare 0 nM protein S for wild type and variants with the open triangle [no APC]). The inclusion of wild-type recombinant protein S to a final concentration of ∼1.5 nM was sufficient to promote the inactivation of 50% of the factor Va present (Figure 4, ▪). Extensive testing showed that purification of protein S from the supernatants was not required for this assay to remain specific for protein S function. Commercially available human plasma–purified protein S had comparable activity to the wild-type preparation, requiring 1.0 nM protein S for 50% inactivation (Figure4, ♦). Furthermore, dialyzed conditioned medium from cells transfected with the vector pcDNA6, diluted to the same extent as 20 nM wild-type protein S, had no activity in this assay (Figure 4, ⋄). Under the conditions employed, factor Va was stable over the course of the assay, and protein S did not have any APC-independent effects (Figure 4, ▵). When the variants were tested, 15.2-fold more of the Gly11Asp variant was required to achieve a 50% reduction in factor Va activity compared to wild-type protein S. This indicated that this mutation resulted in a protein that acted as a poor cofactor to APC. In the case of the Thr37Met variant, 3.6-fold more was required for a 50% reduction in factor Va activity compared to the wild type, indicating a milder, but still significant, impairment of function.

Enhancement of APC-dependent factor Va inactivation by wild-type protein S and variants.

A range of recombinant protein S concentrations (0 to 20 nM) was incubated with 0.1 nM APC, 3 nM factor Va, and 25 μM phospholipid vesicles for 2 minutes at 37°C. Remaining factor Va activity was then quantified using a prothrombinase assay, assessing thrombin generation with the chromogenic substrate S2238 (see text). Results are expressed relative to the remaining activity, with no protein S present (100%), as mean of 3 experiments ± SD. ♦ indicates commercial plasma purified human protein S; ▪, wild-type recombinant protein S; ●, protein S with Gly11Asp; ▴, protein S with Thr37Met; ⋄, dialyzed conditioned medium from cells transfected with the vector pcDNA6 diluted to the same extent as that for 20 nM wild-type protein S; ▵, 20 nM wild-type recombinant protein S added in the absence of APC.

Enhancement of APC-dependent factor Va inactivation by wild-type protein S and variants.

A range of recombinant protein S concentrations (0 to 20 nM) was incubated with 0.1 nM APC, 3 nM factor Va, and 25 μM phospholipid vesicles for 2 minutes at 37°C. Remaining factor Va activity was then quantified using a prothrombinase assay, assessing thrombin generation with the chromogenic substrate S2238 (see text). Results are expressed relative to the remaining activity, with no protein S present (100%), as mean of 3 experiments ± SD. ♦ indicates commercial plasma purified human protein S; ▪, wild-type recombinant protein S; ●, protein S with Gly11Asp; ▴, protein S with Thr37Met; ⋄, dialyzed conditioned medium from cells transfected with the vector pcDNA6 diluted to the same extent as that for 20 nM wild-type protein S; ▵, 20 nM wild-type recombinant protein S added in the absence of APC.

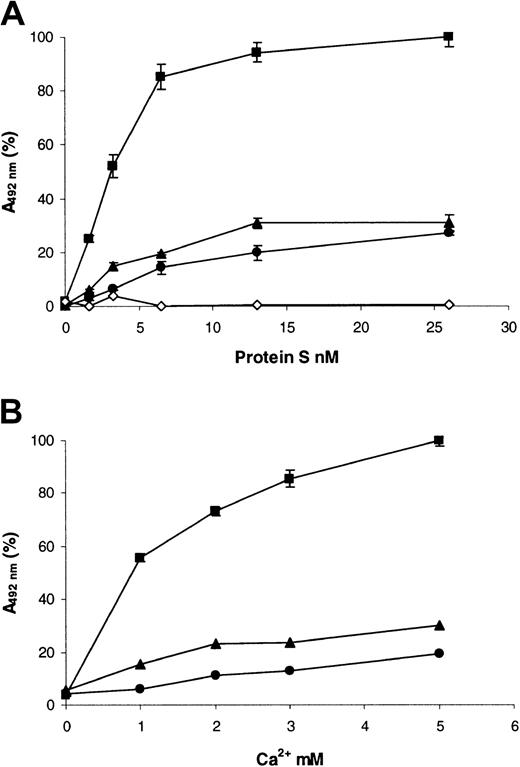

Because both the mutations identified caused substitutions within the Gla domain of protein S, we postulated that the loss of function of the variants was due to impaired Ca2+-induced binding to phospholipid. In order to validate this, a microtiter plate–based assay was used to assess saturation binding to PC/PS/PE (40:40:20) vesicles (Figure 5A; Table2). In the presence of EDTA, wild-type protein S did not bind to the vesicles (Figure 5A, ⋄), indicating the background in the assay was minimal. Wild-type recombinant protein S bound to the vesicles in a saturable manner, with a Kd app of ∼4 nM in a buffer that contained 3 mM CaCl2 (Figure 5A, ▪). The affinity for phospholipid vesicles of the Gly11Asp variant was significantly decreased 5.4-fold when compared to the wild type (Table 2). In the case of the Thr37Met variant, the affinity also was significantly reduced, but only by 1.5-fold (Table 2). For both variants, there was also a reduction in the apparent binding capacity of the phospholipid in comparison with the wild type (Figure 5A; Table 2). When the binding to vesicles without PE (PC/PS, 80:20) was examined, there was no detectable binding at < 10 nM protein S for either wild type or variants (results not shown). However, at higher concentrations of protein S, there was binding of wild-type protein S. The binding of both Gly11Asp and Thr37Met variants was again reduced compared to the wild type (results not shown).

Binding of recombinant human protein S to phospholipid vesicles.

PE/PC/PS 40:40:20 phospholipid vesicles were coated onto the wells of microtiter plates and blocked with 3% (wt/vol) BSA. (A) Dialyzed recombinant protein S (0 to 26 nM) was incubated in the wells for 2 hours at 37°C in a buffer containing 3 mM CaCl2, and bound protein S was detected with a polyclonal anti–human protein S peroxidase-conjugated antibody (see text). (B) Dialyzed recombinant protein S (10 nM) was incubated in the wells for 2 hours at 37°C in a buffer containing various concentrations of CaCl2 (0 to 5mM), and bound protein S was detected with a polyclonal anti–human protein S peroxidase-conjugated antibody (see text). In both panels, results are expressed as mean A492nm of 3 experiments ± SD (in many cases the SDs are so small they cannot be visualized) as a proportion of the maximum (designated 100%). ▪ indicates wild-type protein S; ●, protein S with Gly11Asp; ▴, protein S with Thr37Met; ⋄, wild-type protein S assessed in a buffer that contained no Ca2+ and was instead supplemented with 5 mM EDTA.

Binding of recombinant human protein S to phospholipid vesicles.

PE/PC/PS 40:40:20 phospholipid vesicles were coated onto the wells of microtiter plates and blocked with 3% (wt/vol) BSA. (A) Dialyzed recombinant protein S (0 to 26 nM) was incubated in the wells for 2 hours at 37°C in a buffer containing 3 mM CaCl2, and bound protein S was detected with a polyclonal anti–human protein S peroxidase-conjugated antibody (see text). (B) Dialyzed recombinant protein S (10 nM) was incubated in the wells for 2 hours at 37°C in a buffer containing various concentrations of CaCl2 (0 to 5mM), and bound protein S was detected with a polyclonal anti–human protein S peroxidase-conjugated antibody (see text). In both panels, results are expressed as mean A492nm of 3 experiments ± SD (in many cases the SDs are so small they cannot be visualized) as a proportion of the maximum (designated 100%). ▪ indicates wild-type protein S; ●, protein S with Gly11Asp; ▴, protein S with Thr37Met; ⋄, wild-type protein S assessed in a buffer that contained no Ca2+ and was instead supplemented with 5 mM EDTA.

Equilibrium binding of protein S to PC/PS/PE vesicles

| Protein S . | Kd appnM . | Capacityapp* . |

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 4.3 ± 0.70 | 3.20 ± 0.20 |

| Gly11Asp | 23.6 ± 2.8† | 1.38 ± 0.10† |

| Thr37Met | 6.6 ± 0.10‡ | 1.10 ± 0.20‡ |

| Protein S . | Kd appnM . | Capacityapp* . |

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 4.3 ± 0.70 | 3.20 ± 0.20 |

| Gly11Asp | 23.6 ± 2.8† | 1.38 ± 0.10† |

| Thr37Met | 6.6 ± 0.10‡ | 1.10 ± 0.20‡ |

The units of capacityapp are OD492nm and therefore should be used only to compare between variants.

P < .0001 compared to wild type.

P < .001 compared to wild type.

The reduced phospholipid binding could have been caused by altered affinity of the Gla domain for Ca2+. Therefore, the ability of 10 nM protein S to bind phospholipid vesicles at various concentrations of Ca2+ was assessed in the same microtiter-plate assay (Figure 5B). No significant binding of proteins to phospholipid was observed when they were diluted in a buffer that did not contain Ca2+ ions (Figure 5B; 0 mM CaCl2). For wild-type protein S, the presence of even low concentrations of Ca2+ ions was sufficient to cause a large increase in protein S binding (Figure 5B; ▪, 1 mM CaCl2). Binding was enhanced by further increases in Ca2+ ion concentrations, and this began to approach saturation at 5 mM CaCl2. In contrast, for both of the protein S variants, the amount bound did not increase appreciably between 1 and 5 mM CaCl2 and was strongly reduced compared to the wild type. This suggested that their reduced phospholipid binding was not solely a result of reduced affinity for Ca2+ ions.

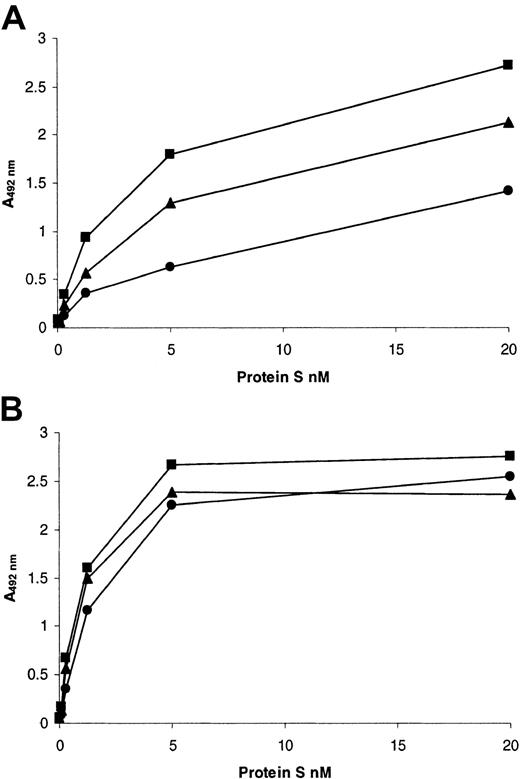

A potential additional explanation for reduced phospholipid binding was due to alteration of the Ca2+-dependent conformation of the Gla domain. We therefore assessed the ability of wild-type and variant protein S to bind to a Ca2+-dependent monoclonal antibody that was directed toward the Gla domain of protein S (HPS21, Figure6A). Both of the variants showed reduced binding to this antibody. The Thr37Met variant had only a modestly reduced affinity for HPS21 compared to the wild type, whereas that of the Gly11Asp variant was more than 3-fold reduced. It is interesting to note that both variants still bound detectably to this conformation- and Ca2+-dependent antibody. As expected, there was no alteration in the affinity of either variant for a Ca2+-dependent monoclonal antibody directed toward the first EGF-like domain (HPS54, Figure 6B), which indicated that this adjacent domain was correctly folded.

Interaction of recombinant human protein S with Ca2+-dependent monoclonal antibodies.

Antibodies were coated into the wells of microtiter plates at 10 μg/mL and blocked with casein. Dialyzed recombinant protein S at a range of concentrations was incubated for 1 hour at 37°C in the presence of 3 mM CaCl2. Bound protein S was detected by means of a rabbit anti–human protein S peroxidase-conjugated antibody. (A) HPS21; (B) HPS54. In both panels, results are expressed as mean A492nm of duplicates as a proportion of the maximum (designated 100%). Each of the duplicates gave essentially identical results. ▪ indicates wild-type protein S; ●, protein S with Gly11Asp; ▴, protein S with Thr37Met.

Interaction of recombinant human protein S with Ca2+-dependent monoclonal antibodies.

Antibodies were coated into the wells of microtiter plates at 10 μg/mL and blocked with casein. Dialyzed recombinant protein S at a range of concentrations was incubated for 1 hour at 37°C in the presence of 3 mM CaCl2. Bound protein S was detected by means of a rabbit anti–human protein S peroxidase-conjugated antibody. (A) HPS21; (B) HPS54. In both panels, results are expressed as mean A492nm of duplicates as a proportion of the maximum (designated 100%). Each of the duplicates gave essentially identical results. ▪ indicates wild-type protein S; ●, protein S with Gly11Asp; ▴, protein S with Thr37Met.

Discussion

Two missense defects (Gly11Asp and Thr37Met) have been identified within the exon of PROS1 that encodes the Gla domain in a proposita with phenotypic protein S deficiency and recurrent thrombosis. The effect of these mutations on expression and function of protein S have been investigated using recombinant techniques. These studies showed that substitution of Gly11Asp did not affect expression of protein S but did result in a molecule that was estimated to be ∼15-fold less active than wild-type protein S in a factor Va inactivation assay. Substitution of Thr37Met reduced production by ∼33%, and the variant protein that was exported successfully had ∼3.5-fold reduced activity. This was not due to gross misfolding of the protein S variants, as the variants bound with similar affinity to a Ca2+-dependent monoclonal antibody directed toward the first EGF-like domain (known to be essential for protein S function; Dahlback et al10 and Figure 6B).

The location of both of the amino acid substitutions suggested a mechanism by which the activity was reduced, as the protein S amino-terminal Gla domain is highly homologous to the corresponding regions of other vitamin K–dependent coagulation proteins, reviewed in Zwaal et al,11 Nelsestuen et al,12 and Stenflo and Dahlback.13 The primary essential function of this domain is to provide the interaction site for anionic phospholipid surfaces, such as those exposed when platelets or endothelial cells are activated and/or damaged. Each Gla domain contains between 9 and 12 residues of γ-carboxyglutamic acid (Gla), which are formed by posttranslational γ-carboxylation of Glu residues.14Gla residues endow this domain with metal-binding properties, and upon addition of Ca2+ ions, Gla domains undergo a dramatic conformational transition, leading to the exposure of a phospholipid-binding site. The Ca2+ transition results in the internalization of most Gla residues, as well as most Ca2+ ions, so that they are located inside the core of the Gla domain and are not solvent-exposed.15-18 Insights into the nature of the phospholipid binding site have been made by comparison of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) structures of the factor IX Gla-domain peptide saturated either with Mg2+or Ca2+. The Mg2+-saturated peptide cannot bind phospholipid and has a structure that is compact and well ordered between residues 12 and 46, but disordered between residues 1 and 11 (with the exception of residues 6 to 9).19 The Ca2+-saturated peptide, which binds phospholipid with normal affinity, is compact and well ordered throughout, including residues 1 to 11 (known as the ω-loop).16 It therefore seems that the ω-loop must be folded correctly for membrane binding to occur and that residues within this loop are crucial for the interaction.19 Indeed, a chimeric factor IX molecule that contains the Gla domain of factor VII (that binds phospholipid only very weakly) did not bind to endothelial cells, but binding was restored after replacement of residues 3-11 of factor IX,20 and residues 4-6 and 9-10 seemed to be particularly important.21

Although these conformational changes are certain to be required for phospholipid binding, the precise mechanism by which the binding occurs is still controversial. Two different hypotheses are currently proposed. The first hypothesis concerns a conserved patch of solvent-exposed hydrophobic residues, at positions Phe4, Leu5, and Val8 (within the ω-loop of bovine prothrombin).15 It is proposed that these residues insert into the hydrophobic core of phospholipid bilayers, and this has found to be the case for Trp4 (substituted for Phe4).22 Furthermore, mutagenesis studies in protein C showed that hydrophobic residues at homologous positions are important for the interaction with membranes.23-25 An alternative hypothesis for phospholipid binding has been proposed based on the observation that although the Gla domains of vitamin K–dependent proteins have a high degree of homology, they display a 1000-fold range in membrane affinity.26 Residues at positions 11, 33, and 34 (in bovine prothrombin) were proposed as candidate residues for membrane contact27 and mutagenesis studies of factor VII and protein C seem to support this hypothesis.28 29 While it is not yet apparent whether these mutations had global changes in Gla-domain structure, these investigations suggest that residues other than the hydrophobic patch may be responsible for differences in membrane affinity.

We hypothesized that the reduced activity of both identified protein S variants could be due to abnormal Ca2+-induced folding of the Gla domain with consequent defective phospholipid binding. This is supported by our results, which showed a variation in the severity of the latter between the 2 variants. Both variants demonstrated reduced ability to bind phospholipid vesicles containing PC/PS/PE (Figure 5A) in the presence of Ca2+, reflected in differences in theKd app (Table 2). The Gly11Asp variant had a Kd app that was increased more than 5-fold compared to the wild type, but this was only increased 1.5-fold for Thr37Met (Table 2). This reflected the greater functional deficit of the Gly11Asp variant in the presence of PC/PS/PE vesicles (Figure 4) compared to Thr37Met. In addition to reduced affinity, both variants had an apparent decrease in the number of binding sites available to them on the surface of these vesicles, as the A492nm at saturation was more than 2-fold reduced for both variants, indicating that less protein S was bound (Table 2). This was not due to specific loss of PE-dependent sites on the vesicles, as both variants also showed reduced binding to vesicles that contained only PC and PS (data not shown). A reduction in the number of binding sites for protein S in the factor Va inactivation assay probably contributes to the functional deficit of these variants.

In this study, using a microtiter plate–based assay, the apparentKd app of wild-type recombinant protein S for PC/PS/PE-containing vesicles was ∼4 nM. This agrees well with previous estimates of phospholipid affinity that varied between 4 and ∼75 nM, using PC/PS-30-33 or PC/PS/PE-8containing vesicles or endothelial cells34 and protein S from different sources. Our preliminary data suggest that the presence of PE in the vesicles increases the affinity of protein S, and to our knowledge this has not been addressed directly before. However, protein S has been shown previously to enhance the binding of protein C to phospholipids in a PE-dependent manner.35

The ability of the variants to bind HPS21, a monoclonal antibody specific for the Ca2+-dependent conformation of the protein S Gla domain,10 was tested to further investigate the mechanism for reduced phospholipid binding. Both variants were found to have reduced affinity (Figure 6A) and, again, the effect was greater for Gly11Asp compared to Thr37Met. However, as an interaction with this antibody (and indeed phospholipid) was detectable under our assay conditions, this suggested that the variants were still able to undergo some form of the Ca2+ transition. It seems that in both cases, the Ca2+-dependent conformation of the Gla domain is disturbed or less stable, resulting in reduced affinity with, and availability of, phospholipid binding sites. Although the defective binding to phospholipid of both variants could not be corrected readily by increasing the concentration of Ca2+ ions (Figure 5B), it remains possible that impaired affinity for Ca2+ ions also contributes to the folding defects. It is interesting that the Thr37Met variant bound to a consistently greater degree compared to Gly11Asp in the Ca2+ titration curves for phospholipid binding (Figure 5B). This corresponds well to its consistently greater activity in the factor Va inactivation assay (Figure 4) and affinity for phospholipid (Figure 5A) and HPS21 (Figure 6A). Direct Ca2+-binding studies would be required to confirm any reduction in affinities for these variants. The probable structural consequences of each amino acid substitution are considered below.

In the absence of any 3D structures for protein S, a theoretical model of the structure of the amino terminal domains of protein S (Gla domain, thrombin sensitive region, and first EGF-like domain) has previously been constructed.36 In this model, the consequence of the Thr37Met substitution has already been examined. Thr37 was noted to be strictly conserved between Gla domains and to be buried in the protein S model. Therefore, when substituted for Met, the much larger side chain could not be accommodated and steric clashes were predicted with the backbone atoms of Arg28.36 This would be expected to lead to the disruption of the α-helical structure of residues 34-45. Our results suggest that such a disruption impacts on secretion of the variant protein (Figure 2). The reduced function of the secreted variant (Figure 4) could also be related to a disruption of this region (often referred to as the aromatic stack), which is thought to be important for the optimal alignment of the protein on phospholipid or cell surfaces.37 However, the reduced availability of phospholipid binding sites to the variant (Figure 5) indicates that the integrity of the aromatic stack is also important for efficient phospholipid binding. The reduced affinity for HPS21 (Figure 6A) suggests that the aromatic stack is also involved in obtaining the correct structure following the Ca2+transition and, potentially, for Ca2+ affinity. The Thr37Met mutation had been reported previously in association with quantitative protein S deficiency.4 38 Here, we show that it is also functionally defective.

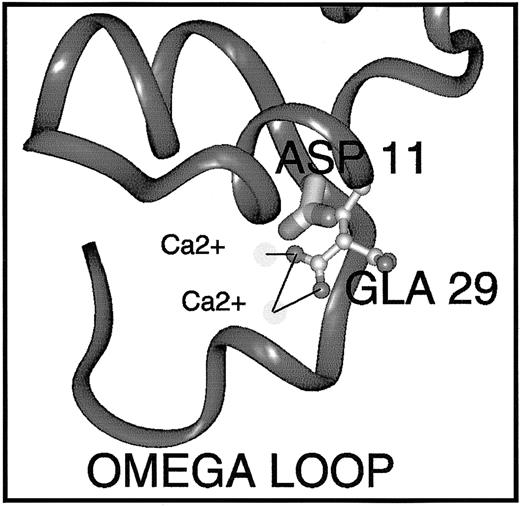

Gly11Asp, at the carboxy-terminus of the ω-loop, is a novel mutation in PROS1. We therefore examined the possible effects of this substitution in the same protein S model using Insight II software.36 In the model, the side chain hydrogen of Gly11 projects into the core of the Ca2+-dependent structure of this region. Therefore, it is unsurprising that its substitution by aspartic acid (an acidic, charged amino acid of medium size) is unfavorable. In order to be accommodated at all, the side chain must take on a fairly radical conformation and even so provokes steric clashes with Gla29 (Figure 7), which would undoubtedly lead to some remodeling of this region, including the ω-loop. The possible repositioning of Gla29 is interesting because this residue has been found in mutagenesis studies to be crucial for the function and/or phospholipid binding ability of factor X, prothrombin, and APC.39-41 In the protein S model, it coordinates 2 Ca2+ ions, and the repositioning may result in loss of Ca2+ ion coordination. This may destabilize the Ca2+-loaded Gla-domain conformation, or reduce the affinity of the Gla domain for Ca2+ ions, resulting in reduced affinity for phospholipid vesicles (Figure 5A). In addition, Gla29 is part of a hydrophilic patch on factor X that is proposed to play a part in postulated ionic interactions with phospholipid and Ca2+bridging.18 Gly11 is conserved in all the vitamin K–dependent proteins with the exception of protein C, which carries Ser at this position. Mutation of Ser11Gly in protein C increases its affinity for phospholipid, suggesting that Gly at this position is crucial for the phospholipid interaction,29 irrespective of Gla29 repositioning. Naturally occurring mutations at the homologous position in factor IX have been reported in association with hemophilia B.42,43 It seems that the precise nature of the amino acid substitution has a bearing on whether the protein is secreted, as homozygous mutation of Gly12Arg in factor IX results in < 1% factor IX activity and 45% antigen,42 whereas, in protein S, the Gly11Asp mutation is tolerated for expression and secretion of the protein (Figure 2).

Predicted effect of the Gly11Asp mutation on the conformation of the protein S Gla domain.

The Gla domain of protein S shown was derived by homology modeling and refinement.36 In order to predict the effects of the Gly11Asp amino acid substitution on protein S structure and function, the Insight II 3D Graphics Program (Accelrys, San Diego, CA) was used. The alpha-carbon backbone trace is shown in dark gray ribbon representation. The side-chain of Asp11 (mutated from Gly11) is depicted in thick stick representation shaded by atom type. The side-chain of Gla29 is depicted in ball-and-stick style, also colored by atom (carbon, pale gray; oxygen, mid-gray). Two Ca2+ions that are coordinated (black lines) by the Gla29 side-chain are shown as very pale spheres. Replacement of wild-type Gly11 by Asp causes multiple bad contacts with atoms of the neighboring Gla29 side-chain, likely to result in loss of Ca2+ ion coordination, Ca2+ ion affinity, and destabilization of the Ca2+-dependent conformation of the Gla domain that is required for interaction with phospholipids.

Predicted effect of the Gly11Asp mutation on the conformation of the protein S Gla domain.

The Gla domain of protein S shown was derived by homology modeling and refinement.36 In order to predict the effects of the Gly11Asp amino acid substitution on protein S structure and function, the Insight II 3D Graphics Program (Accelrys, San Diego, CA) was used. The alpha-carbon backbone trace is shown in dark gray ribbon representation. The side-chain of Asp11 (mutated from Gly11) is depicted in thick stick representation shaded by atom type. The side-chain of Gla29 is depicted in ball-and-stick style, also colored by atom (carbon, pale gray; oxygen, mid-gray). Two Ca2+ions that are coordinated (black lines) by the Gla29 side-chain are shown as very pale spheres. Replacement of wild-type Gly11 by Asp causes multiple bad contacts with atoms of the neighboring Gla29 side-chain, likely to result in loss of Ca2+ ion coordination, Ca2+ ion affinity, and destabilization of the Ca2+-dependent conformation of the Gla domain that is required for interaction with phospholipids.

This study highlights the importance of the high affinity interaction between protein S and anionic phospholipids for its anticoagulant functions both in vitro and in vivo. Our findings with the recombinant proteins provide an explanation for the phenotypic and clinical data obtained from the family. The proposita was a compound heterozygote and had free protein S levels just below the lower limit of the normal range, and this is now attributed to heterozygosity for the Thr37Met mutation. The activity levels were strongly reduced, and this can now be attributed to the functional deficit characterized in both populations of protein S. The proposita has suffered early onset thrombosis associated with pregnancy, as well as recurrences. No other genetic defect could be detected, and it therefore seems that the compound heterozygous state for protein S presents sufficient risk to result in thrombosis when interacting with the acquired risk presented by pregnancy. In contrast, her clinically unaffected son (who was heterozygous only for the Thr37Met mutation) had borderline levels of protein S antigen and low/borderline levels of protein S activity, reflecting the partial secretion and functional defect associated with this mutation.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Dr Geoff Kemball-Cook for the preparation of Figure 7. We also thank Prof Bjorn Dahlback for kindly providing monoclonal antibodies to protein S, and Dr Helen Philippou for advice regarding stable expression of protein S.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, June 14, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0909.

Supported by a grant from the Brazilian government (Agencia CAPES) and grants from the British Heart Foundation.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Rachel E. Simmonds, Haematology Department, Division of Investigative Science, Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College of Science, Technology, and Medicine, Hammersmith Hospital, Du Cane Road, London W12 0NN, United Kingdom; e-mail:r.simmonds@ic.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal