Abstract

The erythroid-specific isoform of 5-aminolevulinate synthase (ALAS2) catalyzes the rate-limiting step in heme biosynthesis. The hypoxia-inducible factor–1 (HIF-1) transcriptionally up-regulates erythropoietin, transferrin, and transferrin receptor, leading to increased erythropoiesis and hematopoietic iron supply. To test the hypothesis that ALAS2 expression might be regulated by a similar mechanism, we exposed murine erythroleukemia cells to hypoxia (1% O2) and found an up to 3-fold up-regulation of ALAS2 mRNA levels and an increase in cellular heme content. A fragment of the ALAS2 promoter ranging from −716 to +1 conveyed hypoxia responsiveness to a heterologous luciferase reporter gene construct in transiently transfected HeLa cells. In contrast, iron depletion, known to induce HIF-1 activity but inhibit ALAS2 translation, did not increase ALAS2 promoter activity. Mutation of a previously predicted HIF-1–binding site (−323/−318) within this promoter fragment and DNA-binding assays revealed that hypoxic up-regulation is independent of this putative HIF-1 DNA-binding site.

Introduction

The first and regulatory step of heme biosynthesis in animals is catalyzed by 5-aminolevulinate synthase (ALAS).1 In addition to the ubiquitously expressed housekeeping isozyme (ALAS1), the erythroid-specific ALAS isozyme (X-chromosome–encoded ALAS2) provides the large quantity of heme required by erythroid cells for hemoglobin production.2,3ALAS2 is expressed exclusively in erythroid cells, and ALAS2 gene defects result in impaired heme biosynthesis, as observed in X-linked sideroblastic anemia.4,5 Enhanced synthesis of hemoglobin during erythropoiesis requires a coordinated production of heme molecules, globin chains, iron delivery, and iron uptake. Expression of proteins responsible for hemoglobin synthesis is therefore interconnected by several regulatory mechanisms, including erythroid-specific transcription factors, cellular heme concentration, and iron status through iron-responsive elements (IREs) located in untranslated mRNA regions.6 7

Hypoxia up-regulates the expression of proteins involved in iron metabolism, including transferrin,8 transferrin receptor,9 and ceruloplasmin.10 The 5′ regulatory regions of these genes contain functional hypoxia-response elements (HREs), mediating transcriptional activation by the hypoxia-inducible factor–1 (HIF-1). HIF-1 is a heterodimeric transcription factor containing an oxygen-labile α-subunit.11 Because hypoxia induces several HIF-1 target genes involved in erythropoiesis, and considering that ALAS2 regulates heme biosynthesis, it is conceivable that ALAS2 expression might be regulated by the same oxygen-dependent mechanisms. Indeed, a single putative HIF-1 DNA-binding site (HBS) has been identified previously within the promoter region of the murine ALAS2 gene.12 Here, we present the first functional analysis of oxygen-regulated ALAS2 expression.

Study design

Cell culture

Murine erythroleukemia (MEL) and HeLa cells were cultured as described.13 Differentiation of MEL cells was induced with 1.8% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) 24 hours before hypoxic (1% O2) or normoxic (20% O2) exposure. Where indicated, 16 μM ciclopirox olamine (CPX)14 or 100 μM desferrioxamine (DFX)15 were added to the medium.

Protein analysis and cellular heme content

DNA-binding assays

Preparation of nuclear extracts from HeLa cells and electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were carried out as described.16 A double-stranded oligonucleotide (TCTCCACGTGGACTTGCC) containing the predicted ALAS2 HBS was used as a probe. Oligonucleotides containing a mutated HBS (TCTCCAAAAGGACTTGCC) or an erythropoietin 3′ enhancer–derived HBS16 served as negative and positive controls, respectively.

mRNA analysis

Site-directed mutagenesis

A pGL2-derived firefly luciferase reporter construct encompassing the −718 to +1 region of the mouse ALAS2 promoter12 was used as a template for site-directed mutagenesis of the HBS at position −323/−318. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) procedure was performed as described,12 with the use of the following primers: ALAS-KpnI (5′-ATATGGTACCCTAGAATCCAATCCATTAC-3′); ALAS-mutant reverse (5′-GCAAGTCCAAAAGGAGAGGACC-3′); ALAS-mutant forward (5′-GGTCCTCTCCTTTTGGACTTGC-3′); and reverse ALAS-HindIII (5′-ATATAAGCTTAGTGCTGTGGGCTGGGCTG-3′). The PCR product was inserted into KpnI-HindIII–digested pGL2, resulting in pTH15. As a control, subcloning of a PCR product amplified with the primers ALAS-KpnI and RALAS-HindIII, which contained the wild-type HBS, resulted in pTH10. Mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Reporter gene assays

Results and discussion

Hypoxic induction of ALAS2 promoter activity

Hypoxic exposure as well as treatment with the iron chelators CPX14 and DFX15 led to stabilization of HIF-1α in MEL cells differentiated by adding DMSO 24 hours before hypoxic exposure (Figure 1A). To analyze whether ALAS2 mRNA steady-state levels were inducible by hypoxia like other genes involved in erythropoiesis, MEL cells were cultured under hypoxic (1% O2) or normoxic conditions for 24 and 48 hours, respectively. As shown in Figure 1B, DMSO treatment led to a strong up-regulation of ALAS2 mRNA expression. Interestingly, hypoxic exposure of differentiated cells induced the mRNA levels of ALAS2 and glucose transporter-1 (Glut-1), a known HIF-1 target gene,19 up to 3-fold, indicating that expression of both genes is influenced by oxygen-regulated pathways. Since ALAS2 protein catalyzes the rate-limiting step in heme synthesis, relative heme content was indirectly estimated following normoxic or hypoxic exposure by measuring its pseudoperoxidase activity. As shown in Figure1C, the heme content was significantly (P < .05; n = 3; Student t test) increased after 48 hours of hypoxic exposure, demonstrating that hypoxic up-regulation of ALAS2 mRNA results in physiologic heme production during erythroid differentiation.

Oxygen-regulated ALAS2 expression.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of nuclear proteins (80 μg) prepared from undifferentiated and DMSO-treated MEL cells cultured under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. Hypoxic HeLa cells were used as a positive control. The iron chelators CPX and DFX were added where indicated, and cells were cultured under normoxic conditions. HIF-1α was detected by using a chicken anti–HIF-1 polyclonal antibody immunoglobulin Y (IgY), described previously,25 followed by a rabbit anti–chicken horseradish peroxidase–coupled secondary antibody. The signal obtained with an anti–Sp-1 antibody was used as a control for loading and transfer efficiency. (B) Representative Northern blot of undifferentiated and DMSO-treated MEL cells cultured under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. The same blot was subsequently hybridized with the indicated cDNA probes. The ribosomal protein L28 cDNA probe was used to correct for loading differences. (C) Measurement of heme pseudoperoxidase activity in undifferentiated and DMSO-treated MEL cells cultured under normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 48 hours. Heme activity was determined by colorimetry based on 2,7-diaminofluorene. Relative activity units were normalized to the normoxic pseudoperoxidase activity of undifferentiated MEL cells, which was arbitrarily defined as 1. Means ± SDs of 3 independent experiments are shown. (D) Luciferase reporter gene assays of transiently transfected HeLa cells cultured under normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 16 hours. ALAS2 promoter–driven firefly luciferase expression plasmids contained either a wild-type (pTH10) or mutant (pTH15) putative HBS. A simian virus 40 (SV40) promoter–driven luciferase reporter gene construct, containing 3 copies of either wild-type or mutant erythropoietin (EPO) 3′ enhancer–derived HBSs, served as a control. A cotransfected renilla luciferase expression vector served as an internal control for transfection efficiency and extract preparation. Relative light units were normalized to the normoxic firefly luciferase activities, which were arbitrarily defined as 1. Means ± SDs of 7 independent transfections are shown.

Oxygen-regulated ALAS2 expression.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of nuclear proteins (80 μg) prepared from undifferentiated and DMSO-treated MEL cells cultured under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. Hypoxic HeLa cells were used as a positive control. The iron chelators CPX and DFX were added where indicated, and cells were cultured under normoxic conditions. HIF-1α was detected by using a chicken anti–HIF-1 polyclonal antibody immunoglobulin Y (IgY), described previously,25 followed by a rabbit anti–chicken horseradish peroxidase–coupled secondary antibody. The signal obtained with an anti–Sp-1 antibody was used as a control for loading and transfer efficiency. (B) Representative Northern blot of undifferentiated and DMSO-treated MEL cells cultured under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. The same blot was subsequently hybridized with the indicated cDNA probes. The ribosomal protein L28 cDNA probe was used to correct for loading differences. (C) Measurement of heme pseudoperoxidase activity in undifferentiated and DMSO-treated MEL cells cultured under normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 48 hours. Heme activity was determined by colorimetry based on 2,7-diaminofluorene. Relative activity units were normalized to the normoxic pseudoperoxidase activity of undifferentiated MEL cells, which was arbitrarily defined as 1. Means ± SDs of 3 independent experiments are shown. (D) Luciferase reporter gene assays of transiently transfected HeLa cells cultured under normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 16 hours. ALAS2 promoter–driven firefly luciferase expression plasmids contained either a wild-type (pTH10) or mutant (pTH15) putative HBS. A simian virus 40 (SV40) promoter–driven luciferase reporter gene construct, containing 3 copies of either wild-type or mutant erythropoietin (EPO) 3′ enhancer–derived HBSs, served as a control. A cotransfected renilla luciferase expression vector served as an internal control for transfection efficiency and extract preparation. Relative light units were normalized to the normoxic firefly luciferase activities, which were arbitrarily defined as 1. Means ± SDs of 7 independent transfections are shown.

Previous analysis of the 5′-flanking region (−1440 to +1) of the mouse ALAS2 gene revealed the presence of several binding sites for erythroid-specific transcription factors as well as a putative HBS (CCACGTGG) at position −318 to −323.12 The predicted HBS shares a high similarity with HBSs found in the promoters of genes encoding insulinlike growth factor–binding protein and lactate dehydrogenase A. To test whether oxygen regulation of ALAS2 expression is mediated by HIF-1, fragments ranging from −716 to +1 and containing either a wild-type (pTH10) or a mutated (pTH15) HBS were inserted upstream of a promoterless luciferase reporter gene vector. Because differentiated MEL cells could not be transfected (data not shown), HeLa cells were used instead. Previous reports showed that the ALAS2 promoter activity is comparable in MEL and HeLa cells.12 20 Hypoxic exposure led to a 2.7-fold induction of luciferase expression (Figure 1D), suggesting that hypoxic induction of ALAS2 is regulated at the transcriptional level. The similarity of the hypoxic induction factors in ALAS2 promoter activity and ALAS2 mRNA levels do not suggest (but also do not formally exclude) that increased mRNA stability contributes to the ALAS2 mRNA induction. However, hypoxic induction of the ALAS2 promoter activity persisted when a construct containing a mutation in the predicted HBS was used (Figure 1D).

Hypoxic up-regulation of ALAS2 is HIF-1 independent

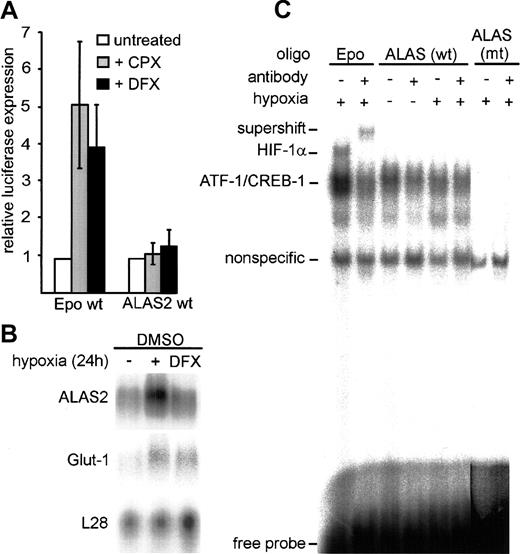

Iron chelators are known to functionally stabilize HIF-1α.14 15 However, in contrast to HeLa cells transfected with a control plasmid containing erythropoietin-derived HBSs, no significant increase in ALAS2 promoter activity was observed following DFX and CPX treatment (Figure2A). In line with this result, Northern blot analysis revealed that DFX leads to an up-regulation of the HIF-1 target gene Glut-1, but not of ALAS2 (Figure 2B).

HIF-1 independence of hypoxic up-regulation of ALAS2.

(A) Firefly luciferase reporter gene constructs, containing either 3 copies of wild-type erythropoietin 3′ enhancer–derived HBSs or a wild-type ALAS2 promoter fragment (pTH10) were transiently transfected into HeLa cells with or without the addition of the iron chelators DFX and CPX. Cells were cultured for 16 hours under normoxic conditions. Results were normalized as described in Figure 1D. Mean ± SD of 3 independent transfections are shown. (B) Northern blot of DMSO-treated MEL cells cultered under normoxic conditions, with the addition of DFX, or under hypoxic conditions. The ribosomal protein L28 cDNA probe was used as a control for loading and transfer efficiency. (C) DNA-binding assays of nuclear extracts derived from HeLa cells cultured under normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 24 hours. HIF-1 DNA-binding activity was determined in nuclear extracts (5 μg) by means of oligonucleotide probes containing the predicted ALAS2 HBS or an erythropoietin 3′ enhancer–derived HBS. The specificity of HIF-1 DNA binding was confirmed by supershift analysis with the use of the anti–HIF-1α monoclonal antibody mgc3.25 wt indicates wild type; mt, mutant.

HIF-1 independence of hypoxic up-regulation of ALAS2.

(A) Firefly luciferase reporter gene constructs, containing either 3 copies of wild-type erythropoietin 3′ enhancer–derived HBSs or a wild-type ALAS2 promoter fragment (pTH10) were transiently transfected into HeLa cells with or without the addition of the iron chelators DFX and CPX. Cells were cultured for 16 hours under normoxic conditions. Results were normalized as described in Figure 1D. Mean ± SD of 3 independent transfections are shown. (B) Northern blot of DMSO-treated MEL cells cultered under normoxic conditions, with the addition of DFX, or under hypoxic conditions. The ribosomal protein L28 cDNA probe was used as a control for loading and transfer efficiency. (C) DNA-binding assays of nuclear extracts derived from HeLa cells cultured under normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 24 hours. HIF-1 DNA-binding activity was determined in nuclear extracts (5 μg) by means of oligonucleotide probes containing the predicted ALAS2 HBS or an erythropoietin 3′ enhancer–derived HBS. The specificity of HIF-1 DNA binding was confirmed by supershift analysis with the use of the anti–HIF-1α monoclonal antibody mgc3.25 wt indicates wild type; mt, mutant.

In EMSAs, an erythropoietin-derived HBS16 resulted in an HIF-1 DNA-binding complex that could be supershifted with the use of a specific anti–HIF-1α antibody (Figure 2C). In contrast, no hypoxia-inducible signal could be observed with the putative HBS derived from the ALAS2 promoter. We therefore conclude that despite the high similarity of the putative ALAS2 HBS core sequence to other HIF target genes, mismatches in the flanking region inhibit an effective DNA-protein interaction. Nonfunctional putative HBSs were also found in the mouse gene encoding HIF-1α itself.21

Taken together, our data demonstrate that ALAS2 transcription is hypoxically induced in an HIF-1–independent manner, leading to an increase in heme content. HIF-1–independent hypoxia-inducible pathways have previously been reported for other genes, including IAP-2 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor type 2.22,23 As iron depletion is known to inhibit ALAS2 translation,24 hypoxic induction of ALAS2 transcription has probably evolved to be HIF-1 independent, as the HIF-1 pathway is activated by iron depletion.

We are grateful to C. Bauer for helpful discussions.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, August 29, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0773.

Supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (M.G.) and the National Institutes of Health (G.C.F.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Max Gassmann, Institute of Veterinary Physiology, University of Zurich, Winterthurerstrasse 260, CH-8057 Zurich, Switzerland; e-mail: maxg@access.unizh.ch.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal