Abstract

The directed migration of mature leukocytes to inflammatory sites and the lymphocyte trafficking in vivo are dependent on G protein–coupled receptors and delivered through pertussis toxin (Ptx)–sensitive Gi-protein signaling. In the present study, we explored the in vivo role of G-protein signaling on the redistribution or mobilization of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HPCs). A single injection of Ptx in mice elicits a long-lasting leukocytosis and a progressive increase in circulating colony-forming unit-culture (CFU-C) and colony-forming unit spleen (CFU-S). We found that the prolonged effect is sustained by a continuous slow release of Ptx bound to red blood cells or other cells and is potentially enhanced by an indirect influence on cell proliferation. Plasma levels of certain cytokines (interleukin 6 [IL-6], granulocyte colony-stimulating factor [G-CSF]) increase days after Ptx treatment, but these are unlikely initiators of mobilization. In addition to normal mice, mice genetically deficient in monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1), matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9), G-CSF receptor, β2 integrins, or selectins responded to Ptx treatment, suggesting independence of Ptx-response from the expression of these molecules. Combined treatments of Ptx with anti–very late activation antigen (anti-VLA-4), uncovered potentially important insight in the interplay of chemokines/integrins, and the synergy of Ptx with G-CSF appeared to be dependent on MMP-9. As Ptx-mobilized kit+ cells display virtually no response to stromal-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) in vitro, our data suggest that disruption of CXCR4/SDF-1 signaling may be the underlying mechanism of Ptx-induced mobilization and indirectly reinforce the notion that active signaling through this pathway is required for continuous retention of cells within the bone marrow. Collectively, our data unveil a novel example of mobilization through pharmacologic modulation of signaling.

Introduction

Heterotrimeric guanosine triphosphate (GTP)–binding proteins (G proteins) participate in one of the most important signaling cascades used to relay extracellular signals in eukaryotic cells. Activation of G proteins and their effectors mediate a broad spectrum of cellular responses initiated by receptors coupled to G proteins (GPCRs). The nature of the response to a stimulus in any given cell is dictated by the receptor density, type of G protein activated, its duration of activation (also influenced by regulator proteins [RGS]), and the complement of effector molecules in each cell type.1-4 G proteins have been functionally categorized by their susceptibility to bacterial toxins. The widely distributed Gi and Gs proteins are inhibited by pertussis toxin (Gi), or activated by cholera toxin (Gs). Pertussis toxin (Ptx) in particular has been instrumental in delineating signaling pathways dependent on G proteins. Much of the evidence favoring G-protein involvement in T-cell function is derived from studies using Ptx to block Gi function. In vivo, Ptx causes lymphocytosis by inhibiting lymphocyte migration from blood to tissues, or across lymph node endothelium.5-8 In mature leukocytes, chemotactic receptors and their ligands signal through G proteins, and such signaling is essential for their adhesion and directed migration to inflammatory sites. This G protein–dependent effect is suppressed by Ptx.9-11 Leukemic cell metastases also appear to be mediated through G-protein signaling,12-17 although only certain G proteins are involved in some tissues.14 Signals from CXCR4R, a GPCR present in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HPCs),18-20 are important for their maintenance within bone marrow (BM).21-23 Down-regulation of CXCR4 function leads to mobilization of stem/progenitor cells,24-26 although conflicting views have been presented as to the nature of CXCR4/stomal-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) signaling required for mobilization.27 The mechanistic effects of CXCR4/SDF-1 signaling on hematopoietic cells, either immature or mature, are dependent on integrin activation, and are largely delivered through Ptx-sensitive G proteins.28-30

To directly address the in vivo effects of G-protein signaling on the migration of HPCs from BM to blood or other tissues, we treated mice with Ptx and assessed its impact on mobilization of HPCs. We found that in addition to the expected leukocytosis, there was a protracted effect on HPC mobilization. Detailed in vitro studies using the plasma or cells from Ptx-treated animals have uncovered helpful insights for interpreting the longevity of the Ptx effect. The type of functional impairment of mobilized cells after Ptx treatment and the responses of several murine knockout models also provided a framework for approaching some of the molecular dynamics brought by Ptx treatment in vivo.

Materials and methods

Animals

All mice used in this study were housed under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions and were free from known mouse pathogens. B6D2F1 mice, WCB6F1 Sl/Sld or Steel-Dickie and WCB6F1 (+/+) littermates, WBB6F1 (W/Wv) mice with WBB6F1 (+/+) littermates were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). The origin of mice deficient in granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor (G-CSFR-/-), metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9-/-), monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1-/-), or CD18 (CD18-/-) and selectin (E+L+P-/-) has been mentioned previously.31,32 Both Tpo-/- mice and double knockout Tpo-/-, G-CSFR-/- mice were kindly provided by Dr K. Kaushansky (University of California at San Diego). Nonobese/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mice were from Jackson Laboratories and Rag2-/- from Taconic (Oxnard, CA). In addition to mice, one pigtailed monkey (Macaca nemestrina) was used and was housed in the facilities of the accredited University of Washington Regional Primate Center.

Antibodies and reagents

Anti-CD49d (very late activation antigen 4 [VLA-4] or α4) was kindly provided by Dr Roy Lobb (Biogen, Cambridge, MA) and anti-CD106 (vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 [VCAM-1]) was purchased from Southern Biotech (Birmingham, AL). These contained no azide and low endotoxin (NA/LE). The following antibodies, either purified or directly conjugated, were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA): anti-CD3, anti-CD11a (leukocyte function associated antigen 1 [LFA-1]), anti-CD31 (platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 [PECAM-1]), anti-CD41, anti-CD117 (c-kit), Sca-1, GR-1, TER-119, CD45R/B220, anti-CXCR4, and anti-CD29. Directly conjugated anti-VLA-4 was purchased from Southern Biotech. Ptx, Ptx B oligomer, and cholera toxin were purchased from List Biological Laboratories (Campbell, CA). Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF; filgrastim) was purchased from Amgen (Thousand Oaks, CA). Fucoidan was from Sigma (St Louis, MO), and murine SDF-1 was from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ). Both the annexin V detection kit and the bromodeoxyuridine (BrDU) flow kit were from BD Pharmingen.

Plasma cytokine and chemokine assays

Levels of cytokines and chemokines in murine or primate plasma from peripheral blood (PB) or BM were analyzed by the Cytokine Analysis Laboratory, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (FHCRC; Seattle, WA). Endotoxin levels in plasmas from treated or control mice were analyzed by the Biologics Production Facility at FHCRC.

Cell cycle analysis and BrDU incorporation

For cell cycle analysis, 106 BM or spleen cells were permeabilized with PET buffer (phosphate-buffered saline plus [PBS] 1.0 mM EDTA [ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid] plus 0.1% Triton X-100) for 30 minutes on ice and labeled with propidium iodide (2 μg/mL), and were then analyzed on a FACS Calibur (BD Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA) using ModFit-LT software (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME). To study actively proliferating cells, BrDU was injected at 167 mg/kg body weight intraperitoneally twice during the 24 hours before Ptx injection. An aliquot of white blood cells (WBCs) from lysed blood and BM 3 days after Ptx injection was stained with kit-APC at 106 cells/mL for 30 minutes at 4°C. Control aliquots were stained with isotype control antibody. Cells were processed and stained with anti-BrDU-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), as per BD Pharmingen protocol, then analyzed by flow cytometry.

CFU-C assay

Colony-forming unit-culture (CFU-C) assays were performed using a methylcellulose mixture and cytokine cocktail and were counted as described previously.30 Colonies were scored as granulocyte-macrophage colony-forming units (CFU-GM), mixed colony-forming units (CFU-Mix), erythroid burst-forming units (BFU-E), and on some experiments as megakaryocyte colony-forming units (CFU-Meg). All types of colonies are reported as CFU-Cs.

Radioprotection

Primary recipient mice were irradiated with 1200 cGy from a cesium source (at the dose rate of > 100 cGy/min) and then injected intravenously with either 0.1 mL or 0.2 mL blood from Ptx-treated or normal mice. The survival of mice for the next 30 days was recorded and moribund animals were humanely killed.

SDF-1–dependent chemotaxis

PB collected in heparin was layered over Histopaque 1.083 (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO), centrifuged, and interface cells washed. To obtain lineage-negative (Lin-) cells, we incubated them with lineage-specific antibodies (anti-CD3, -CD45R/B220, -CD11b, GR-1, and TER-119) followed by secondary antibody treatment and negative selection using a Midi-MACS system (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Lin- PB cells were adjusted to 2 × 106/mL and migration assays through 5-μm Transwells (Corning Costar, Cambridge, MA) were performed as described.33 Migrated cells were collected from the bottom wells and total cells counted. The percentage of migrated cells was calculated relative to the total number of cells inoculated in the upper chamber.

SDF-1–dependent actin polymerization

Lin-depleted cells isolated as described were adjusted to 1 × 106 cells/mL in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM) plus 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and stimulated with SDF-1 at 100 ng/mL at 37°C.34 At indicated time points, 100-μL aliquots were fixed in 100 μL 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS. The cells were then permeabilized and stained with Phalloidin Alexa 568 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), as described34 and analyzed on a FACSCalibur. To test the effect of red blood cells (RBC) or plasma from Ptx-treated mice on SDF-1–induced actin polymerization, 1 × 106 Jurkat (human lymphoid cell line) cells were incubated overnight with either plasma or washed RBCs from both untreated mice and Ptx-treated mice, then assayed as described (see “SDF-1–dependent chemotaxis”).

Results

Ptx induces a long-lasting mobilization of HPCs

The effect of Ptx on leukocyte redistribution was described more than 3 decades ago. To test whether Ptx could also increase circulating HPCs and to find the effective doses required, we treated groups of mice with a single injection of Ptx at 3 different doses (100, 200, 400 ng) and quantitated WBCs and circulating HPCs 3 days later. After Ptx treatment, a significant lymphocytosis and granulocytosis and a significant increase in circulating HPCs (from 10- to 20-fold above baseline) was documented. Because no significant differences were seen among the 3 doses tested, we adopted a dose of 100 ng/mouse in all subsequent experiments. To define the kinetics of CFU-C response relative to WBC increase, several groups of mice were treated with a single injection of 100 ng Ptx and analyzed at 1, 3, and 24 hours and daily thereafter for 8 days.

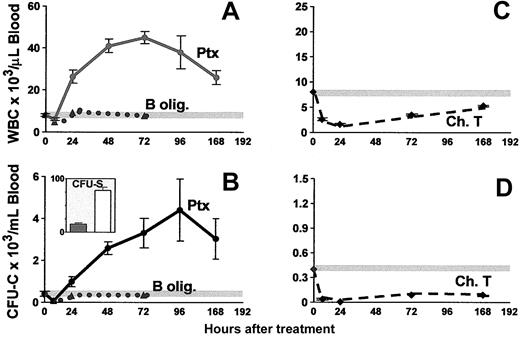

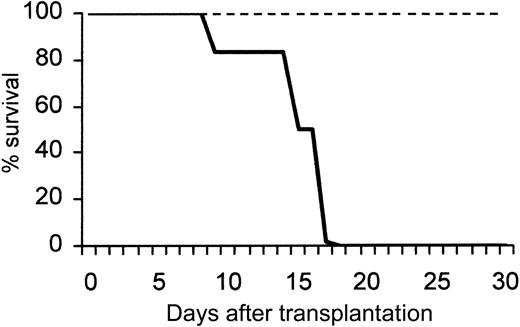

Figure 1 shows a peak in leukocytosis at about 72 hours (45 035 ± 3248 WBC/μL blood), and a peak in CFU-C levels at about 96 hours (4403 ± 1610 CFU-C/mL blood). An absolute increase in all lymphocyte subsets (data not shown) and in granulocytes was seen, as previously noted.35 After Ptx treatment all classes of committed progenitors (BFU-E, CFU-GM, CFU-Meg, and CFU-Mix) were mobilized and found in proportions similar to ones in control mice (data not shown). In splenectomized animals, higher CFU-C mobilization was noted peaking at later times (day 7, CFU-Cs: 6237 ± 911 and WBCs: 42 916 ± 2436, n = 5). To test whether earlier progenitors like CFU-Ss and radioprotective cells were mobilized, we carried out short-term transplantation experiments using blood from Ptx-treated animals. For these experiments, an aliquot of blood (0.1 or 0.2 mL) from control or treated animals (a single injection of Ptx 72 hours previously) was given to each of the lethally irradiated recipients, and their survival was followed. Eleven recipients received blood from Ptx-treated animals and 8 control recipients were given blood from nontreated animals. Two moribund controls along with 5 recipients of blood from Ptx-treated mice were evaluated at day 12 for the presence of CFU-S12 in their spleens (Figure 1B inset). The estimated number of CFU-S12/mL blood in Ptx-treated animals was 78 ± 5.3 (n = 5) and 15 ± 2.2 in the 2 control mice. (The CFU-S levels in control mice were small, barely meeting the criteria of macroscopic colonies.) Furthermore, within the BM of the 5 mice that received blood from Ptx-treated animals, 62.0 ± 14.6 CFU-C/femur were recovered at day 12, and none from the BM of the 2 mice treated with control blood, suggesting the presence of higher numbers of short-term reconstituting cells in Ptx blood. Notably, mice that received blood from Ptx-treated mice survived beyond 5 weeks, whereas all 6 remaining control animals died before day 18 (Figure 2).

Kinetics of WBC and CFU-C peripheralization in mice treated with a single injection of Ptx, B-oligomer, or cholera toxin on day 0. Only the Ptx holotoxin (solid lines), but not B-oligomer (dotted lines), mobilizes CFU-Cs (B) and increases WBCs (A), whereas cholera toxin (dashed lines) causes a prolonged depression of both WBCs (C) and CFU-Cs (D). The inset in panel B depicts CFU-S/mL blood in control (dark bar) and in Ptx-treated (white bar) animals. Horizontal gray lines in panels A-D represent mean control levels.

Kinetics of WBC and CFU-C peripheralization in mice treated with a single injection of Ptx, B-oligomer, or cholera toxin on day 0. Only the Ptx holotoxin (solid lines), but not B-oligomer (dotted lines), mobilizes CFU-Cs (B) and increases WBCs (A), whereas cholera toxin (dashed lines) causes a prolonged depression of both WBCs (C) and CFU-Cs (D). The inset in panel B depicts CFU-S/mL blood in control (dark bar) and in Ptx-treated (white bar) animals. Horizontal gray lines in panels A-D represent mean control levels.

Survival of lethally irradiated mice injected with blood from normal or Ptx-treated mice. A total of 11 mice received blood from Ptx-treated animals (dotted line); 5 of them were killed at day 12 and the rest survived beyond 30 days. None of the mice receiving control blood (bold line; 0.2 mL) survived beyond day 18.

Survival of lethally irradiated mice injected with blood from normal or Ptx-treated mice. A total of 11 mice received blood from Ptx-treated animals (dotted line); 5 of them were killed at day 12 and the rest survived beyond 30 days. None of the mice receiving control blood (bold line; 0.2 mL) survived beyond day 18.

Enzymatic activity of Ptx is required for the HPC-mobilizing effect

Ptx is a typical A-B toxin readily dissociated to S1 or A protomer (the subunit with the catalytic activity) and the pentamer or B-oligomer (responsible for binding to the cell surface). Most of the effects of Ptx on various cell types are attributed to its enzymatic activity,36,37 despite the failure of the A protomer itself to act on intact cells, because the B-oligomer enables the protomer to traverse the plasma membrane to reach the site of action inside the cell. This binding is the first step required for the A protomer adenosine diphosphate (ADP)–ribosyltransferase to enter the cell. To test whether the mobilization of HPCs requires the enzymatic activity of Ptx, or whether the B-oligomer alone can elicit this effect, we treated animals with the B-oligomer and followed changes in WBCs and circulating progenitor cells for several days after this treatment. Two doses were used, 200 and 400 ng/mouse. At 3 hours after injection (Figure 1), a mild depression of cell numbers was seen, and for the next 3 days, the number of either total nucleated WBCs or circulating progenitors never exceeded the average numbers observed in the control animals at baseline. Neither the B-oligomer nor the holotoxin had a direct effect on the proliferation of CFU-Cs when added directly to cultures of BM or PB CFU-Cs at 10 ng/mL (data not shown). Treatment of mice with cholera toxin, which, in contrast to Ptx, activates Gs proteins and stimulates cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), elicited a significant depression of circulating WBCs and progenitors, lasting more than a week (Figure 1C-D).

Surface antigenic profiles and functional responses of Ptx-mobilized HPCs

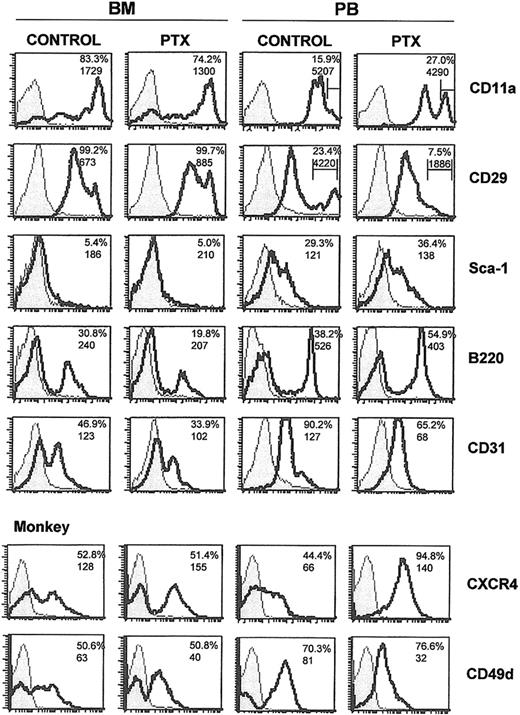

To uncover the identity of mobilized cell populations along with alterations in their surface markers, we tested the expression of several antigens characterizing either progenitor-type cells (ie, kit or Sca-1), or cells of specific lineages (GR-1, MAC-1, TER-119, CD41, CD31, and B220 or CD3). In addition, the abundance of CXCR4 and of certain adhesion molecules, like α4 (CD49d), β1 integrin (CD29), LFA-1 (CD11a), and L-selectin (CD62L), was tested. Analysis was done 3 days after Ptx injection to match the CFU-C mobilization peak, and the data were confirmed in 3 independent experiments. After comparing mobilized cells to those remaining in the BM, we compared BM cells from normal and Ptx-treated animals.

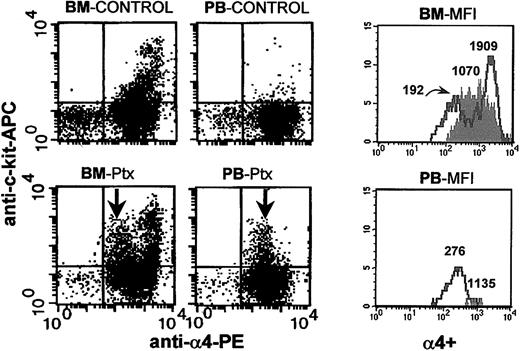

The results of these experiments are presented in Figure 3 and Table 1 and can be briefly summarized as follows. There was a reduction in B220+ lymphoid cells within the BM as expected,7-9 with a concomitant increase in the PB of treated animals (Figure 3); a reduction in CD31+ population in the BM; a significant increase in c-kit+ population in PB; a down-regulation of α4-integrin expression in a subset of

Flow cytometric analysis of BM and PB from normal and mobilized animals. Mononuclear cells from BM and PB from control and Ptx-treated mice and one Ptx-treated monkey (bottom 2 panels) were labeled with directly conjugated antibodies. The shaded areas represent isotype controls and solid lines represent cells labeled by the directly conjugated antibodies noted. Numbers within histograms represent percent positive cells (top numbers) and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI; bottom numbers). Bars in anti-CD11a and anti-CD29 histograms represent proportions of cells with high expression.

Flow cytometric analysis of BM and PB from normal and mobilized animals. Mononuclear cells from BM and PB from control and Ptx-treated mice and one Ptx-treated monkey (bottom 2 panels) were labeled with directly conjugated antibodies. The shaded areas represent isotype controls and solid lines represent cells labeled by the directly conjugated antibodies noted. Numbers within histograms represent percent positive cells (top numbers) and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI; bottom numbers). Bars in anti-CD11a and anti-CD29 histograms represent proportions of cells with high expression.

Proportion of positive cells and MFI

. | BM Control . | BM Ptx* . | Blood Control . | Blood Ptx* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mice | ||||

| c-kit (CD117) | 36.8 (230) | 38.1 (264) | 6.0 (111) | 16.3 (253) |

| L-selectin (CD62L) | 77.4 (156) | 75.9 (139) | 61.3 (72) | 58.3 (49) |

| Integrin αIIb (CD41) | 15.9 (199) | 10.4 (192) | 50.2 (862) | 42.3 (392) |

| TER-119 (Ly-76) | 22.1 (3363) | 34.4 (3324) | 5.6 (2972) | 4.2 (944) |

| CXCR4 (CD184) | 52.9 (53) | 61.4 (58) | 19.2 (63) | 66.0 (55) |

| Monkey | ||||

| LFA-1 (CD11a) | 41.6 (380) | 59.8 (473) | 77.0 (1916) | 98.2 (439) |

| PECAM-1 (CD31) | 37.3 (218) | 49.3 (245) | 50.9 (371) | 83.6 (281) |

| CD34 | 16.2 (150) | 5.8 (43) | 1.6 (85) | 5.9 (49) |

. | BM Control . | BM Ptx* . | Blood Control . | Blood Ptx* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mice | ||||

| c-kit (CD117) | 36.8 (230) | 38.1 (264) | 6.0 (111) | 16.3 (253) |

| L-selectin (CD62L) | 77.4 (156) | 75.9 (139) | 61.3 (72) | 58.3 (49) |

| Integrin αIIb (CD41) | 15.9 (199) | 10.4 (192) | 50.2 (862) | 42.3 (392) |

| TER-119 (Ly-76) | 22.1 (3363) | 34.4 (3324) | 5.6 (2972) | 4.2 (944) |

| CXCR4 (CD184) | 52.9 (53) | 61.4 (58) | 19.2 (63) | 66.0 (55) |

| Monkey | ||||

| LFA-1 (CD11a) | 41.6 (380) | 59.8 (473) | 77.0 (1916) | 98.2 (439) |

| PECAM-1 (CD31) | 37.3 (218) | 49.3 (245) | 50.9 (371) | 83.6 (281) |

| CD34 | 16.2 (150) | 5.8 (43) | 1.6 (85) | 5.9 (49) |

All entries are percentages, followed by MFI in parentheses.

Ptx-treated mice were each injected intravenously with 100 ng of the toxin 3 days earlier. The monkey was injected with 25 μg/kg Ptx.

Anti-c-kit and anti-α4 staining of BM and PB from control (untreated) and Ptx-mobilized animals. Following Ptx treatment, down-regulation of α4-integrin expression in c-kit+ cells from BM and PB is seen. The 4 FACS dot plots on the left show control (upper panels) and Ptx-treated (lower panels) BM and PB. The histograms in the 2 panels on the right show α4 expression in kit+ cells from BM and PB of controls (shaded) and Ptx-treated animals (solid lines). The numbers over the cell peaks indicate the MFIs of control and Ptx-treated (2 peaks) BM and PB cells (one peak).

Anti-c-kit and anti-α4 staining of BM and PB from control (untreated) and Ptx-mobilized animals. Following Ptx treatment, down-regulation of α4-integrin expression in c-kit+ cells from BM and PB is seen. The 4 FACS dot plots on the left show control (upper panels) and Ptx-treated (lower panels) BM and PB. The histograms in the 2 panels on the right show α4 expression in kit+ cells from BM and PB of controls (shaded) and Ptx-treated animals (solid lines). The numbers over the cell peaks indicate the MFIs of control and Ptx-treated (2 peaks) BM and PB cells (one peak).

To investigate whether similar changes can be seen in the primate model, we treated one monkey (M nemestrina) with 25 μg/kg Ptx and recorded the changes in BM and PB 3 days after treatment. A spectacular 45-fold increase in CFU-C levels in PB was noted in this animal (from 118.6 ± 9 to 5359 ± 705 CFU-C/mL of blood). The expression of α4 and CXCR4 in PB and BM (Figure 3) followed the same trends as in mice, but there were some differences (ie, CD31, CD11a; Table 1).

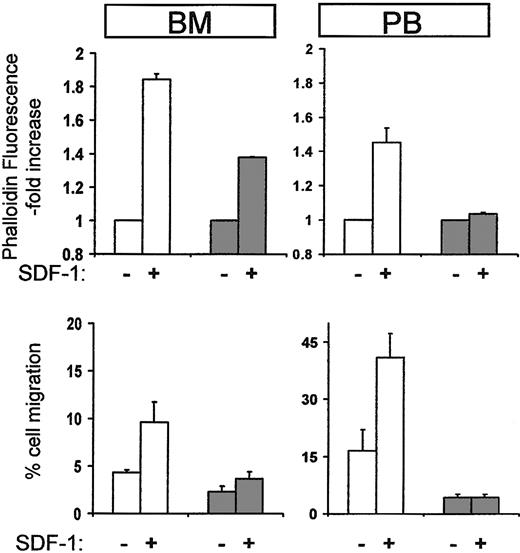

To probe for alterations in the functional properties of Ptx-mobilized cells, we used 2 assays proven useful in previously published studies, that is, a migration assay in response to SDF-1 and actin polymerization in the presence or absence of SDF-1 using phalloidin staining. These showed that Lin-depleted murine cells from Ptx-treated BM or PB exhibited a very blunted response in SDF-1–induced actin polymerization compared with control cells and little or no migration toward SDF-1 showing that both chemokinesis and chemotaxis were reduced (Figure 5). Similar results were obtained when mononuclear or kit+ cells were used instead of Lin- cells (data not shown). These data support a direct functional modification of both mature and immature hematopoietic cells by in vivo administration of Ptx.

Cytoskeletal reorganization and chemotaxis in response to SDF-1 of cells from normal or Ptx-treated mice. Mobilized lineage-depleted cells from Ptx-treated mice did not display SDF-1–induced actin polymerization after 10 seconds (top right panel, PB, dark columns) compared to control cells (white columns). BM cells from treated mice were also modestly affected (top left panel, BM, dark columns). Furthermore, when Lin-/- cells from BM or PB were used for migration assays (bottom panels), cells from Ptx-treated mice (dark columns) were largely SDF-1 unresponsive.

Cytoskeletal reorganization and chemotaxis in response to SDF-1 of cells from normal or Ptx-treated mice. Mobilized lineage-depleted cells from Ptx-treated mice did not display SDF-1–induced actin polymerization after 10 seconds (top right panel, PB, dark columns) compared to control cells (white columns). BM cells from treated mice were also modestly affected (top left panel, BM, dark columns). Furthermore, when Lin-/- cells from BM or PB were used for migration assays (bottom panels), cells from Ptx-treated mice (dark columns) were largely SDF-1 unresponsive.

Other Ptx-elicited effects

To explore the protracted response of Ptx-induced mobilization, the following studies were done. Plasma from controls or Ptx-treated animals at several time points after treatment (3-5 days and 10 days) were tested using sensitive in vitro assays. To probe for persistence of Ptx-like activity, Jurkat cells were used as target cells and their response to SDF-1–induced actin polymerization was recorded (Figure 6).

Ptx-like activity of plasma from Ptx-treated mice after incubation with Jurkat cells as targets. After overnight incubation with plasma from Ptx-treated animals [(+) Ptx P], Jurkat cells displayed a Ptx-like defect in SDF-1–induced actin polymerization. Normal plasma [(+) NP] was similar to untreated Jurkat cells [(-) P]. A similar effect was observed when Jurkat cells were incubated with washed RBCs from normal or Ptx-treated mice suggesting a sustained release of Ptx from cellular depots as an explanation for its lingering effect (data not shown). Apart from RBCs, other hematopoietic or nonhematopoietic cells (ie, endothelial cells) could theoretically contribute to this effect, but these were not directly tested.

Ptx-like activity of plasma from Ptx-treated mice after incubation with Jurkat cells as targets. After overnight incubation with plasma from Ptx-treated animals [(+) Ptx P], Jurkat cells displayed a Ptx-like defect in SDF-1–induced actin polymerization. Normal plasma [(+) NP] was similar to untreated Jurkat cells [(-) P]. A similar effect was observed when Jurkat cells were incubated with washed RBCs from normal or Ptx-treated mice suggesting a sustained release of Ptx from cellular depots as an explanation for its lingering effect (data not shown). Apart from RBCs, other hematopoietic or nonhematopoietic cells (ie, endothelial cells) could theoretically contribute to this effect, but these were not directly tested.

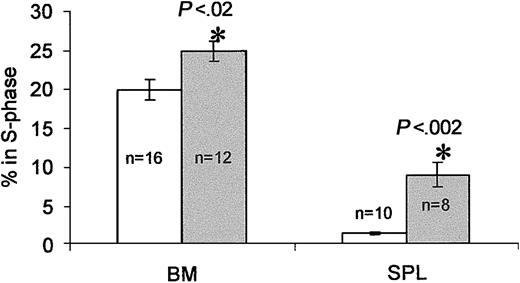

Plasma collected between days 3 and 5 after treatment exerted a Ptx-like effect on these cells, whereas plasma at day 10 after treatment behaved as control plasma. We speculated that the enzymatic activity detected in plasma was likely released from cellular elements, that is, RBCs, that serve as depots of Ptx toxin6 and could explain its protracted effect on cells. This turned out to be true (data not shown). To inquire whether proliferative effects were present after Ptx treatment, we evaluated the proportion of cycling cells in BM and spleen (by propidium iodide or BrDU labeling of kit+ cells on day 3). Although there were small, nonstatistically significant increases in the cellularity of BM and spleen, there were significant elevations in the cycling of cells (control BM, 19.9% ± 1.3% in S phase versus Ptx BM, 24.8% ± 1.3%, P < 0.02; control spleen cells, 1.35% ± 0.2% versus Ptx spleen cells, 8.75% ± 1.5%, P < 0.002; Figure 7). Further evidence was provided by BrDU experiments documenting an increase in BrDU+ cells at day 3 after Ptx in BM and also a higher proportion of kit+ cells that were BrDU+ (25% in Ptx treated versus 20% in controls). To test whether cytokine/chemokine levels changed after Ptx treatment and mediated the effects on proliferation, we analyzed plasma samples from the Ptx-treated monkey before and during the 3 days after treatment by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs; with the exception of SDF-1α and β, the assays available to us were for human rather than murine sources). In the PB, only interleukin 6 (IL-6) and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) showed significant changes (Table 2). The levels of G-CSF were modestly increased and unlikely to be responsible for mobilization, although such levels could provide a proliferative stimulus if sustained. The IL-6 levels by day 3 were high, but its significance in mobilization is unclear in view of the general anesthesia required for each blood sampling in primates, the effects of Ptx on liver,38 and the fact that similar changes have been seen previously with other treatments in monkeys albeit with different kinetics.32 Its importance, however, should be further evaluated in IL-6-/- mice. SDF-1 levels in PB remain unchanged, but there is a trend of SDF-1 reduction in BM samples (Table 2). Finally, it is of note that annexin V labeling tested in control and Ptx-treated BM and PB showed no significant differences between control and Ptx-treated cells (data not shown).

Cell cycle analysis of BM and spleen cells 3 days after Ptx treatment. Cells from BM and spleens of Ptx-treated mice (gray bars) show significant increases in the proportion of cells in S phase compared with cells from untreated mice (white bars. Numbers (n) indicate numbers of mice tested. The percent of cells in S phase was calculated on gated (blast window) cells.

Cell cycle analysis of BM and spleen cells 3 days after Ptx treatment. Cells from BM and spleens of Ptx-treated mice (gray bars) show significant increases in the proportion of cells in S phase compared with cells from untreated mice (white bars. Numbers (n) indicate numbers of mice tested. The percent of cells in S phase was calculated on gated (blast window) cells.

Cytokine/chemokine levels after Ptx treatment

Day . | WBC count, 1000/μL . | CFU-C level, no./mL . | IL-6 level, pg/mL . | IL-8 level, pg/mL . | MCP-1 level, pg/mL . | G-CSF level, pg/mL . | SCF level, pg/mL . | SDF-1α level, pg/mL . | SDF-1β level, pg/mL . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monkey* | |||||||||

| PB | |||||||||

| -1 | 8.3 | 118.6 ± 9.0 | <2.0 | 119.0 | 130.0 | <2.0 | <120.0 | <160.0 | <120.0 |

| +1 | 43.0 | 254 ± 65.6 | <2.0 | 64.5 | <32.0 | <2.0 | 70.5 | <240.0 | <240.0 |

| +2 | 36.7 | 377.4 ± 52.9 | 436.6 | 121.6 | 362.8 | 170.9 | 47.6 | <240.0 | <240.0 |

| +3 | 64.0 | 5359 ± 705.6 | 2199.5 | 131.5 | 257.5 | 317.8 | 36.0 | <240.0 | <240.0 |

| BM | |||||||||

| -1 | ND | ND | <2.0 | 345.2 | 237.4 | 6.2 | <120.0 | 12 188.0 | 8319.5 |

| +3 | ND | ND | 1109.5 | 143.5 | 441.5 | 213.7 | <120.0 | 2948.3§ | 1948.8§ |

| Mouse† | |||||||||

| Baseline‡ | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1856 ± 119 | <120.0 |

| PB, +3 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1349 ± 253 | <120.0 |

| BM, +3 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 4539 ± 41∥ | 816 ± 64.9 |

Day . | WBC count, 1000/μL . | CFU-C level, no./mL . | IL-6 level, pg/mL . | IL-8 level, pg/mL . | MCP-1 level, pg/mL . | G-CSF level, pg/mL . | SCF level, pg/mL . | SDF-1α level, pg/mL . | SDF-1β level, pg/mL . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monkey* | |||||||||

| PB | |||||||||

| -1 | 8.3 | 118.6 ± 9.0 | <2.0 | 119.0 | 130.0 | <2.0 | <120.0 | <160.0 | <120.0 |

| +1 | 43.0 | 254 ± 65.6 | <2.0 | 64.5 | <32.0 | <2.0 | 70.5 | <240.0 | <240.0 |

| +2 | 36.7 | 377.4 ± 52.9 | 436.6 | 121.6 | 362.8 | 170.9 | 47.6 | <240.0 | <240.0 |

| +3 | 64.0 | 5359 ± 705.6 | 2199.5 | 131.5 | 257.5 | 317.8 | 36.0 | <240.0 | <240.0 |

| BM | |||||||||

| -1 | ND | ND | <2.0 | 345.2 | 237.4 | 6.2 | <120.0 | 12 188.0 | 8319.5 |

| +3 | ND | ND | 1109.5 | 143.5 | 441.5 | 213.7 | <120.0 | 2948.3§ | 1948.8§ |

| Mouse† | |||||||||

| Baseline‡ | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1856 ± 119 | <120.0 |

| PB, +3 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1349 ± 253 | <120.0 |

| BM, +3 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 4539 ± 41∥ | 816 ± 64.9 |

ND indicates not determined.

In addition to the chemokines/cytokines listed, we also determined IL-1α, M-CSF, and GM-CSF levels, but these did not show any changes from pretreatment levels.

BM and PB values represent means from 4 animals.

Baseline levels were derived from PB of 15 BDF1 mice.

Significant reduction in SDF-1 level is seen; however, this sample was diluted with PB. For the same reason, it is unclear to what extent IL-6 and G-CSF are increased in BM.

When calculated per femur, this level is about 50% lower than baseline values obtained previously.32

Mobilization by Ptx in several transgenic knockout models

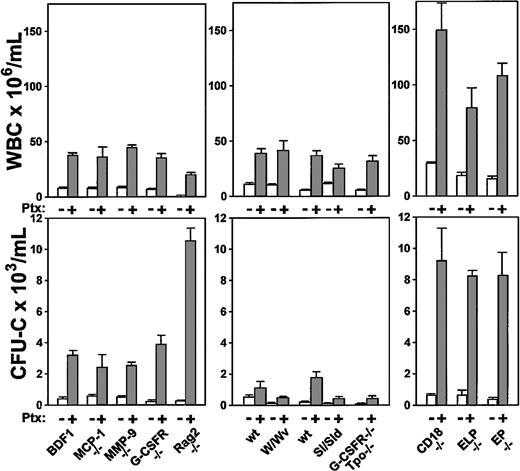

Because the in vivo effects of Ptx on mobilization are not immediate and show a delayed and progressive pattern, the sequence of molecular events leading to this process are difficult to unravel. To approach this issue in an indirect manner, we treated transgenic animal models deficient in MCP-1, MMP-9, G-CSFR, and CD18 integrins or in selectins, to explore the putative or indirect participation of any of these molecules in Ptx-induced mobilization. Rag 2-/- mice were also treated to test whether mobilization of a lymphoid population was in some indirect way contributing to the maintenance of mobilization. Three to 5 mice were used per group and evaluated 3 days after a single injection of 100 ng Ptx per mouse. The results of this study are depicted in Figure 8.

Increments in WBCs and in circulating CFU-Cs of several knockout models following Ptx treatment. Data are recorded at day 3 after treatment and treated or untreated groups included 3 to 5 animals per group. White bars indicate baseline values; gray bars are values after Ptx treatment.

Increments in WBCs and in circulating CFU-Cs of several knockout models following Ptx treatment. Data are recorded at day 3 after treatment and treated or untreated groups included 3 to 5 animals per group. White bars indicate baseline values; gray bars are values after Ptx treatment.

Taking all data from these animals together, several conclusions can be drawn. The fact that Rag-2-/- mice respond excessively with granulocytosis rather than lymphocytosis with a great increase in HPCs suggested that peripheral migration of lymphocytes per se does not influence the granulocytic or the progenitor cell response. The magnitude of progenitor mobilization cannot be predicted by the magnitude of WBC response. W/WV mice responded well in WBCs, but less well in CFU-Cs, despite the fact that their BM CFU-C content is similar to controls.39 Mice with a decrease in stem/progenitor pools (G-CSFR/Tpo-/- mice,40 or the Sl/Sld mice) responded less than their normal counterparts. In Sl/Sld mice, it is also possible that the decreased response is dictated by a decreased contribution of splenic responses, because the documented increased proliferation and cellularity in spleen may not be present in these mice. Mice with already increased baseline levels appear to reach much higher response levels than their normal controls. This is compatible with the expectation that a heightened response may be present in inflammatory situations, such as in CD18 or selectin-deficient animals. Because G-CSFR-/- mice responded similarly or better than their controls, but do not respond to G-CSF– or IL-8–induced mobilization,41 one surmises that G-CSFR or IL-8 signals are not necessary for Ptx-induced mobilization. Likewise, MMP-9-/- mice responded well and although a small increase in MMP-9 protein was seen in normal mice after Ptx treatment (data not shown), this was found after day 3 and is an unlikely contributor to Ptx-induced mobilization.

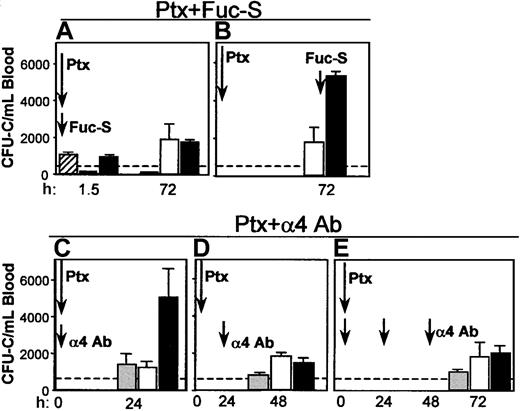

Combination of Ptx with other mobilizing agents

Coadministration of Fuc-S and Ptx. Because Fuc-S (fucoidan) elicits an immediate chemokine-like response (in contrast to Ptx), 2 treatments were designed incorporating either simultaneous or sequential administration of both agents. In the first experiment, both Fuc-S (100 mg/kg) and Ptx (100 ng/mouse) were simultaneously administered intravenously in 6 BDF1 mice. Mice were bled 1.5 hours later and WBC and circulating CFU-C levels were assessed. The same was repeated at 72 hours. The results show that there was leukocytosis and an increase in progenitors (Figure 9A) both at 1.5 hours (reflecting the effect of Fuc-S) and at 72 hours in the combined treatment (reflecting the Ptx effect) with no additive or synergistic effect compared with Ptx alone. Alternatively, when Ptx was given at day 1 and Fuc-S 72 hours later with the animals being bled 1.5 hours after Fuc-S, a very large response was seen in both the WBCs (data not shown) and the CFU-Cs (Figure 9B), above the levels achieved by either Ptx or Fuc-S alone. The heightened response seen when Fuc-S was administered at the peak of the expected Ptx response could denote an expanded pool of cells on which the Fuc-S could exert its mobilizing effect rather than cooperativity.

Coadministration of Fuc-S and Ptx, or anti-α4 and Ptx. Combination treatments of Ptx with Fuc-S (A, B) or anti-α4 (C, D, E) resulted in different outcomes (enhancement or no enhancement of CFU-C/mL blood), depending on whether the 2 compounds were administered concurrently or sequentially with respect to Ptx injection. Bars represent CFU-C levels after injections of Fuc-S alone (striped), Ptx alone (white), anti-α4 alone (gray), and combinations (FucS + Ptx or α4 + Ptx, black). Arrows indicate the time of treatment administration, and times of testing are recorded on the horizontal axis.

Coadministration of Fuc-S and Ptx, or anti-α4 and Ptx. Combination treatments of Ptx with Fuc-S (A, B) or anti-α4 (C, D, E) resulted in different outcomes (enhancement or no enhancement of CFU-C/mL blood), depending on whether the 2 compounds were administered concurrently or sequentially with respect to Ptx injection. Bars represent CFU-C levels after injections of Fuc-S alone (striped), Ptx alone (white), anti-α4 alone (gray), and combinations (FucS + Ptx or α4 + Ptx, black). Arrows indicate the time of treatment administration, and times of testing are recorded on the horizontal axis.

Blockade of α4integrin and Ptx treatment. The impact of combined treatments of Ptx and of antibody blockade of α4 integrin was subsequently tested. Because the mobilization kinetics with Ptx treatment are much slower than with anti-α4 treatment (72 hours versus 24 hours), 2 different schedules of combined anti-α4 and Ptx treatments were evaluated. In the first experiment, a single injection of anti-α4 antibody (PS/2 at 2 mg/kg) plus Ptx was given intravenously simultaneously. Animals given only anti-α4 or only Ptx were used as controls (n = 3). The numbers of circulating leukocytes or progenitors were evaluated before and 24 and 48 hours after the injection. In agreement with previous studies42 a modest increase in WBC levels was seen at 24 hours in the group given anti-α4 (data not shown), whereas a more pronounced leukocytosis was seen in the Ptx group and the group with the combined anti-α4 plus Ptx treatment. Circulating progenitors increased approximately 4-fold at 24 hours in the single treatments with anti-α4 (1431 ± 570/mL) or with Ptx (1271 ± 321/mL). A much higher level was observed in the combined treatment (5090 ± 1536/mL at 24 hours, P < .05; Figure 9C). Because the effect of Ptx is not seen during the first 3 hours, then slowly peaks at days 3 or 4, whereas the effect of anti-α4 peaks during the first 24 hours, to synchronize the maximal effect of each treatment, in the next experiment Ptx injection was given first, followed 24 hours later by one anti-α4 injection. Two other groups of mice received Ptx alone or anti-α4 alone. The mice were evaluated 24 hours after anti-α4 (48 hours after Ptx). Again, the anti-α4 group had the expected 24-hour level of response, but now the Ptx alone group or the group with the combined treatment responded similarly, in contrast to the enhancement seen in the first experiment (Figure 9D). To provide additional data and to maximize the anti-α4 effect, in 2 additional experiments we treated mice with one injection of Ptx plus anti-α4, followed by 2 additional anti-α4 injections, one at 24 hours and another 48 hours later. The results of these experiments (Figure 9E) are basically no different from those of the experiments with sequential Ptx and anti-α4 treatment and, in aggregate, suggest that if the effect of Ptx precedes that of anti-α4 blockade, no additional benefit is derived by the anti-α4 treatment. However, if the antibody treatment has a functional influence before that of Ptx, an enhancement of the mobilizing effect is seen only at early time points. The above data, together with those documenting a down-regulation of VLA-4 expression in BM and PB cells after Ptx (Figures 3 and 4) suggest that a down regulation of VLA-4 function may be a consequence of Ptx-induced mobilization, as seen with other mobilizing agents.39

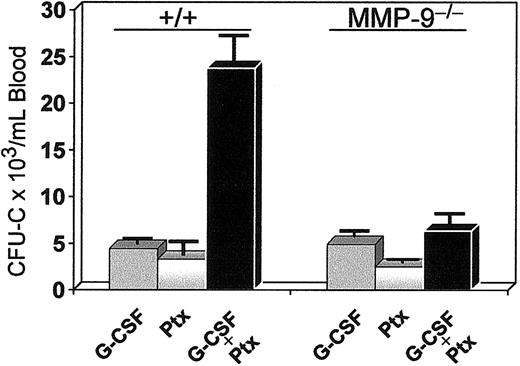

Coadministration of Ptx and G-CSF. G-CSF alone at 100 μg/kg twice daily was administered to one group of 3 mice for 3 days, and 2 other groups (3 mice/group) received either G-CSF (for 3 days) and Ptx (at day 1) or Ptx alone. Seventy-two hours after Ptx injections, a dramatic mobilization of progenitors was noted in the combination treatment compared with G-CSF or Ptx alone (Figure 10), which exceeded the 5-fold effect of G-CSF alone and the 15-fold increase of Ptx alone. Although both agents have a rather protracted response in mobilization, the synergistic rather than additive effect suggests enhanced cooperativity in mobilization between these 2 agents. Because increases in MMP-9 have been previously assigned a critical role in G-CSF–induced mobilization,43 we tested MMP-9-/- mice with either G-CSF or G-CSF plus Ptx (Figure 10). Although G-CSF response in the latter mice was in the expected range of normal (+/+) animals, the synergy of G-CSF with Ptx found in normal mice was largely eliminated, suggesting that it is MMP-9 dependent.

Synergistic mobilization of normal mice treated with G-CSF and a single injection of Ptx. Normal (left 3 bars) and MMP9-/-(right 3 bars) mice were treated with G-CSF alone (100 μg/kg twice daily for 3 days), with Ptx alone (one injection at 100 ng/mouse), or with both (same doses, black bars). Blood was collected on day 4 and cultured for CFU-C levels. The synergy noted in normal animals was practically abolished in MMP9-/-mice (black bar on the far right).

Synergistic mobilization of normal mice treated with G-CSF and a single injection of Ptx. Normal (left 3 bars) and MMP9-/-(right 3 bars) mice were treated with G-CSF alone (100 μg/kg twice daily for 3 days), with Ptx alone (one injection at 100 ng/mouse), or with both (same doses, black bars). Blood was collected on day 4 and cultured for CFU-C levels. The synergy noted in normal animals was practically abolished in MMP9-/-mice (black bar on the far right).

Discussion

A single injection of Ptx elicits a long-lasting lymphocytosis, granulocytosis, and, as shown in the present studies, a sustained increase in circulating hematopoietic progenitor cells. All 3 components of this response are dependent on the presence of the S1 enzymatic activity of the pertussis holotoxin documented here by comparing the effects of B-oligomer that lacks ADP ribosyltransferase activity to that of the holotoxin (Figure 1). Even if clearance between the 2 proteins is different, the B-oligomer was unable to elicit a response during the first 24 hours. What is the long-lasting effect of a single injection of Ptx treatment due to? To provide insight we tested the plasma from Ptx-treated animals several days after treatment for the detection of persisting Ptx-like activity in vitro. The amount of Ptx protein present in plasma at 3 days after treatment or later was capable of inhibiting the SDF-1–induced actin polymerization in vitro in contrast to normal plasma (Figure 6). Such a Ptx-like activity in circulation for several days after a single Ptx injection originates from cellular depots from which it is slowly and continuously being released into the circulation. In addition, an increase in proliferation of HPCs was documented in BM and spleen (Figure 7) that could enhance the sustained increase in circulation of both polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) and progenitor cells. We speculate that the effects on proliferation represent a secondary, indirect effect elicited by Ptx treatment. A survey of cytokines up to 4 days after Ptx treatment did not reveal any increase in IL-1α, GM-CSF, macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), or stem cell factor (SCF). However, a significant increase in IL-6 and a modest increase in G-CSF were noted at day 3 (in the monkey), which, if persisted, could contribute to proliferative responses. Elaboration of additional (not identified) diffusible molecules or cytokines responsible for the increased proliferation cannot be excluded. The possibility that a Ptx-induced intrinsic alteration in cell signaling changing not only the adhesive properties, but the cycling of hematopoietic cells was also considered,44,45 but thought to be unlikely, because Ptx added in vitro influenced neither the number nor the size of hematopoietic colonies. Furthermore the effects of Ptx-induced perturbations of CXCR4/SDF-1 (CD184/CXCL12) signaling on proliferation, both in vitro and in vivo, are controversial,46-50 but recent studies suggest that injection of an antagonist (SDF-1-G2) reactivates the cycling of primitive stem cells in vivo.50

The mobilization of stem/progenitor cells observed in our studies with Ptx treatment invite comparisons with previously described mobilization of CFU-S by endotoxin from Escherichia coli or Salmonella typhi.51 High doses of injected endotoxin (500 μg) caused an immediate but transient increase (peak at 1-2 hours) in circulating CFU-S levels, without any increase in total granulocytes or total WBCs, and a later peak several days after treatment. Such a response was not seen in our Ptx-treated animals, in which no responses were documented from 1 to 3 hours. There was also a gradual increase in granulocytes, to heights never seen with the endotoxin, and in progenitor cells for the next 10 days. At no point was there any decrease in bone marrow cellularity, or anemia and thrombocytopenia, as observed in endotoxin-treated animals.51 Our results were induced by the injection of only 100 ng Ptx per mouse, but endotoxin injection even at 100 μg/mouse produced a small or an erratic response.51 Furthermore, endotoxin levels in plasma of our Ptx-treated mice were very low and similar to levels of untreated animals (data not shown). Finally, circulating cells after Ptx treatment showed specific responses in vitro (Figure 5), which are only compatible with the inhibition of Gi-protein signaling.

Responses to Ptx treatment of several murine models with targeted adhesion molecules or cytokines/chemokines led to several indirect conclusions relevant to the mechanism of Ptx-induced mobilization, and support the independence of responses between mature lymphogranulocytic cells and immature HPCs. Of particular note is the response of MMP-9-/- mice to Ptx-induced mobilization. If MMP-9-/- cells fail to respond to SDF-1 as recently suggested,52 one would not expect them to respond to inhibition of its downstream signaling by Ptx, unless the responses seen here are independent of SDF-1. Moreover, the response of the MMP-9-/- mice to G-CSF–induced mobilization was in agreement with previous data,53 but in contrast to other data.52 Nevertheless, the synergy in mobilization seen with G-CSF and Ptx in normal mice was not observed in these mice, possibly implicating the presence of MMP-9 in the synergistic effect.

The precise sequence of molecular interactions leading to mobilization after Ptx treatment is unclear and warrants further exploration with innovative reagents and using mice with altered migratory responses. If in vivo Ptx treatment interrupts signals emanating from G protein–coupled receptors on hematopoietic cells, then one must assume that a major relevant pathway involved is the CXCR4/SDF-1 pathway. There is mounting evidence about the significance of this pathway in homing/engraftment as well as in mobilization of HPCs.54,55 Several experimental approaches, including antibodies, receptor antagonists, or modified chemokine ligands have been used to study its influence and several scenarios have been suggested to explain its effects on hematopoietic homeostasis. Experiments with CXCR4 or SDF-1 knockout mice emphasized the importance of this pathway in the maintenance of adult hematopoiesis within BM.21-23 Furthermore, treatment of normal mice or human volunteers with small molecule antagonists of CXCR4,25,26 or modified forms of SDF-124 leads to mobilization of stem/progenitor cells presumably through the disruption of signals from the CXCR4/SDF-1 pathway. In fact, it has been advocated that such a mechanism is mainly responsible for the G-CSF–induced mobilization.27,56-58 Following G-CSF treatment, an increased release of leukocyte proteinases, especially neutrophil elastase, cathepsin G, or proteinase-3 from PMNs was documented within BM and in circulation.56,57 Such increased levels of serine proteases within BM can attack several target proteins, including CXCR4, SDF-1,56,57 or VCAM-1,58 leading to inactivation of CXCR4/SDF1- or VCAM-1/VLA-4–dependent signals and cell migration out of BM. Although additional mechanisms could be operable in G-CSF–induced mobilization, the concomitant degradation of a receptor and of its ligand,56 or of other endothelial and extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules could magnify perturbation of several adhesion mechanisms maintaining developing hematopoietic cells within BM and would lead to mobilization of stem/progenitor cells. If one assumes that Ptx disrupts downstream signaling through the CXCR4/SDF-1 pathway, as it occurs in vitro, our data are in concert with the studies mentioned above, implicating a disruption of CXCR4/SDF1 signaling in mobilization. Ptx-mobilized cells were more severely crippled in their SDF-1 response than the G-CSF–mobilized cells, although conflicting data are available for the response of G-CSF–mobilized cells to SDF-1.33,59,60 Moreover, such an exacerbated effect on abrogation of SDF-1 signaling together with a possible reduction of SDF-1 within BM (Table 2) and/or an increase in MMP-9 on day 3 after Ptx treatment could explain the synergy of Ptx with G-CSF that we observed. Nevertheless, the picture is far from clear, and other contradictory interpretations have also surfaced. It was recently suggested that activation rather than abrogation of CXCR4/SDF-1 signaling is required for mobilization, because antibodies to CXCR4, or small molecule antagonist (TC14012) for this receptor suppressed the G-CSF–induced mobilization.27 These data are in direct contradiction to other studies showing that CXCR4 antagonists promote mobilization and enhance the G-CSF–induced mobilization.24-26 Whether in vivo treatments with polyclonal antibodies versus different CXCR4 antagonistic molecules with potentially different modes of action could account for these differences is difficult to discern at this point and further experimentation is warranted. On a relevant vein, data with in vitro anti-CXCR4 antibody treatments are inconsistent61-64 and at odds with studies using Ptx-treated cells in homing experiments of murine BM,60 murine fetal liver cells,65 or human CD34+ cells.62 Collectively, the weight of the evidence suggests that CXCR4/SDF-1 signaling may not be crucial for the initial anchoring of transplanted cells to endothelial cells within BM, but their subsequent retention within BM is greatly dependent on CXCR4/SDF-1 signaling. Whether cells from Ptx-treated animals or hematopoietic cells with genetically modified Gi protein signaling35 display a different behavior in homing assays will be addressed in future experiments.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, February 20, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2741.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL46557, HL58734, and RR00166. H.B. is supported by a Mildred Scheel Scholarship of the Deutsche Krebshilfe (German Cancer Research Fund).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We are grateful to Drs Daniel C. Link and Robert M. Senior, both of Washington University School of Medicine for providing the G-CSFR-/- and MMP-9-/- mice, respectively, and Dr Barrett Rollins, Harvard Medical School for MCP-1-/- mice. We are also grateful to Dr A. Beaudet (Baylor College, Houston, TX) for the CD18-/- and EPL-/- mice. We thank Marta Hill for her expert secretarial assistance, Linda M. Scott for the genotyping of CD18-/- mice and Vivian Zafiropoulos for skillful technical assistance.

![Figure 6. Ptx-like activity of plasma from Ptx-treated mice after incubation with Jurkat cells as targets. After overnight incubation with plasma from Ptx-treated animals [(+) Ptx P], Jurkat cells displayed a Ptx-like defect in SDF-1–induced actin polymerization. Normal plasma [(+) NP] was similar to untreated Jurkat cells [(-) P]. A similar effect was observed when Jurkat cells were incubated with washed RBCs from normal or Ptx-treated mice suggesting a sustained release of Ptx from cellular depots as an explanation for its lingering effect (data not shown). Apart from RBCs, other hematopoietic or nonhematopoietic cells (ie, endothelial cells) could theoretically contribute to this effect, but these were not directly tested.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/101/12/10.1182_blood-2002-09-2741/6/m_h81234494006.jpeg?Expires=1767700717&Signature=GFzUA-zZ52E49eTzUcwS0r9kvMlQRBiz8F-Fxo~AKDxAjFOAodQpIkT2RT-ZDiIE0OtTeDIUK0~g-Xk1kY2fi~lJGBAtVmhp3Ownc9Wd4IztgAOtvtdGPKHGHqi-e6bUi-aDzc1HdctaHiU0q82ftEWuOKGGhWsLCtwycyGFAd8a3P4kXdlNuz7qViuips6u2BOzGAFsrI2a35mY65eOE3fz0RP6ccQhSzJfElfY9wj0iypTkSXUUXX17bYPVc13h-glFLhX1GlRJ7~URaEk~koE~7BRUmL3zvmiCIbLrjk2fiSpUCUoym-sUAitivLB1i21Df47KcwxwnHQ-~Zz4w__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal