Abstract

We have examined platelet functional responses and characterized a novel signaling defect in the platelets of a patient suffering from a chronic bleeding disorder. Platelet aggregation responses stimulated by weak agonists such as adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and adrenaline were severely impaired. In comparison, both aggregation and dense granule secretion were normal following activation with high doses of collagen, thrombin, or phorbol-12 myristate-13 acetate (PMA). ADP, thrombin, or thromboxane A2 (TxA2) signaling through their respective Gq-coupled receptors was normal as assessed by measuring either mobilization of intracellular calcium, diacylglycerol (DAG) generation, or pleckstrin phosphorylation. In comparison, Gi-mediated signaling induced by either thrombin, ADP, or adrenaline, examined by suppression of forskolin-stimulated rise in cyclic AMP (cAMP) was impaired, indicating dysfunctional Gαi signaling. Immunoblot analysis of platelet membranes with specific antiserum against different Gα subunits indicated normal levels of Gαi2,Gαi3,Gαz, and Gαq in patient platelets. However, the Gαi1level was reduced to 25% of that found in normal platelets. Analysis of platelet cDNA and gDNA revealed no abnormality in either the Gαi1 or Gαi2 gene sequences. Our studies implicate the minor expressed Gαi subtype Gαi1 as having an important role in regulating signaling pathways associated with the activation of αIIbβ3 and subsequent platelet aggregation by weak agonists.

Introduction

The engagement of the adhesive ligand fibrinogen by its receptor, the integrin αIIbβ3, is critical for the platelet aggregation response. Activation of this receptor is regulated by intracellular signals generated following platelet activation by physiologic stimuli. Considerable evidence exists demonstrating the involvement of different heterotrimeric G protein–coupled signaling pathways in the activation of αIIbβ3.1,2 It is known that Gq-mediated activation of phospholipase C-β (PLC-β) is a prerequisite for platelet aggregation with most agonists. Agonists such as thrombin, adenosine diphosphate (ADP), and thromboxane A2 (TxA2) can activate PLC-β, resulting in the mobilization of intracellular calcium and activation of protein kinase C (PKC), both of which are important intracellular signal elements involved in αIIbβ3 activation.1,2 However, recent work has shown that weak agonists such as ADP also require the simultaneous coactivation of Gi-coupled signaling pathways to elicit the aggregation response. Distinct ADP receptors signal through different G proteins. For example, the P2Y1 receptor is coupled to PLC-β activation via Gαq and the P2Y12 receptor inhibits adenylate cyclase via Gαi.3,4 Adrenaline, when acting through α2A-adrenergic receptors only activates Gαi-signaling pathways and therefore cannot stimulate aggregation unless coadministered with an agonist that activates Gq-signaling pathways such as serotonin.3 Recent studies indicate that Gαi-mediated inhibition of adenylate cyclase and the subsequent lowering of basal cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) is not critical for the Gi component required for aggregation.4,5

Patients suffering from chronic bleeding disorders in whom platelet aggregation is abnormal have provided valuable information with regard to the mechanisms involved in the regulation of αIIbβ3 activation. The most often reported case studies involve patients suffering from Glanzmann thrombasthenia, a hereditary condition in which impaired platelet aggregation is linked to either quantitative or qualitative defects in αIIbβ3 expression.6 In addition, patients with similar phenotypes also have reduced dense and α granular contents.7 More recently there have been several reported cases of patients in whom defects in aggregation were linked to an impaired intracellular signaling mechanism.8 Defects of this type can occur at the level of agonist receptors or less commonly be due to reduced expression of intracellular molecules such as Gαq9 or PLC-β2.10 Patients with congenital defects in ADP receptors have been well characterized and show impaired aggregation responses to ADP and other weak agonists that use an ADP autocrine mechanism.11,12 Additionally, ADP-induced suppression of prostaglandin E1 (PGE1)–induced activation of adenylate cyclase was inhibited; this along with the presence of a reduced number of ADP-binding sites is indicative of defective coupling between the P2Y12 receptor and Gαi2.13 These studies have provided important evidence for the critical role for Gi-coupled pathways in ADP-induced platelet activation. The role played by Gq-coupled pathways has similarly been highlighted in patients with deficiency of either Gαq or PLC-β2 in their platelets.9,10 Such studies have underlined the importance of these molecules and pathways in regulating platelet aggregation.

Here, we report the characterization of a novel G-protein defect in the platelets of a patient suffering from a chronic bleeding disorder. These studies provide evidence for a novel role for Gαi1 in regulating signaling pathways associated with the promotion of aggregation by weak agonists such as ADP and adrenaline.

Patient, materials, and methods

Patient case history

The patient, AD, is a 36-year-old man with a lifelong history of hemorrhagic symptoms, including epistaxis and easy bruising. He has no family history of bleeding disorders and the parents are unrelated. Hematologic investigations revealed a consistently normal platelet count. Measurement of intraplatelet von Willebrand factor, fibrinogen, and nucleotide levels were all within normal limits. Bleeding time was more than 20 minutes, but there were no abnormalities in coagulation as detected by routine diagnostic tests. All blood samples were obtained after informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Materials

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma (Poole, United Kingdom) unless otherwise indicated. Fura-2 acetylmethylester was purchased from Calbiochem-Novabiochem (Nottingham, United Kingdom). The Betray cyclic adenosine 3′-5′-monophosphate (cAMP) enzyme immunoassay system and the radioactive reagents, [3H]arachidonic acid, (210 Ci/mmol; 777 × 1010 Bq), [14C]5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT; 50 mCi/mmol; 1850 MBq), and guanosine 5′γ-[35S]thiotriphosphate (41 TBq/mmol) and phosphorous 32 (carrier-free) were purchased from Amersham Biosciences. [3H]2-methyladenosine 5′-diphosphate ([3H]2-MeSADP; 3 Ci/mmol; 11.1 × 1010 Bq) was from Moravek Biochemicals (La Brea, CA).

Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated monoclonal antibody (MoAb) PAC-1 was from Becton Dickinson (Conley, United Kingdom). Horm-Collagen was from Hormon-Chemie (Munich, Germany) and Polymorphprep was from Axis-Shield (Oslo, Norway).

Antibodies

Specific anti-Gαi1 (catalog nos. 371720 and PC59) and Gαi3 antisera were purchased from CN Biosciences (Nottingham, United Kingdom) and were raised against internal sequences from Gαi1 159-168 and Gαi3 345-354, respectively. Specific anti-Gαi2 (sc-7276), anti-GαZ (sc-388), and anti-Gαq (sc-393) antisera were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-p85 phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI-3K) and c-Src antibodies were from Upstate (Milton Keynes, United Kingdom).

Platelet isolation and labeling with [14C]5HT, [3H]arachidonic acid, and [32P]Pi

Blood was collected by venipuncture into 1:10 volume trisodium citrate (3.2% wt/vol) and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) obtained by centrifuging blood at 200g for 15 minutes. PRP was removed and used immediately for platelet aggregation studies or acidified with 0.1 M citric acid to pH 6.5, and treated with 1 μM PGE1. The PRP was centrifuged at 1000g for 15 minutes and the platelet pellet was washed and resuspended in pH 6.5 buffer composed of 36 mM citric acid, 103 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 0.09% (wt/vol) glucose, and 1 U/mL apyrase. Platelets were then labeled with either [14C]5-HT (0.1 μCi/mL; 0.0037 MBq) for 30 minutes, [32P]orthophosphate (1 mCi/mL; 37 MBq) for 90 minutes, fura 2-AM (5 μM) for 45 minutes, or [3H]arachidonic acid (0.75 mCi/mL; 27.75 MBq) for 90 minutes as described previously.14 At the end of the incubation periods, 1 μM PGE1 was added and the platelet suspension centrifuged at 1000g for 15 minutes and the resulting pellet was resuspended in a pH 7.4 buffer composed of 10 mM HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid), 5 mM KCl, 145 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 1 mM CaCl2, and 0.09% (wt/vol) glucose at a platelet count of 3 to 4 × 108/mL.

Measurement of platelet aggregation, [14C]5-HT secretion, [3H]arachidonate release, TxB2 formation, and pleckstrin phosphorylation

All studies were carried out at 37°C and in a Chrono-Log 4-channel aggregometer. Washed platelets or platelets in PRP (500 μL) were incubated with platelet agonists for 3 minutes. Platelet aggregation was measured as an increase in light transmission as described earlier.15 For [14C]5-HT secretion and [3H]arachidonate release studies, incubations were ended by the addition of ice-cold EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; 16 mM) and formaldehyde (1% vol/vol). The samples were centrifuged at 13 000 rpm for 3 minutes and the supernatant removed for liquid scintillation counting. For thromboxane B2 (TxB2) studies incubations were terminated with the addition of ice-cold mixture of EDTA (16 mM) and indomethacin (10 μM), followed by centrifugation at 13 000 rpm for 3 minutes. The supernatant was removed and TxB2 levels were measured using the Amersham (Philadelphia, PA) Biotrak TxB2 immunoassay kit. For pleckstrin phosphorylation studies, [32P]-labeled platelets were incubated with agonists for 3 minutes, after which 2 × sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer was added and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. The increase in [32P]-labeling in pleckstrin was quantified by autoradiography of the dried gels and counting the radioactivity.

Flow cytometry

Washed platelets (2 × 106 /mL) were activated with either ADP (10 μM), thrombin (0.2 U/mL), or phorbol-12 myristate-13 acetate (PMA; 100 nM) in the presence of FITC-conjugated MoAb PAC-1 or FITC-labeled fibrinogen and incubated for 60 minutes at room temperature without stirring. Platelets were pelleted by centrifugation for 1 minute in a microfuge. Platelets were washed twice and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis. Flow cytometry was carried out using a Becton Dickinson FACScan.

Measurement of diacylglycerol levels

Washed platelets (3 × 108/mL) labeled with 1 μCi/mL (0.037 MBq) [3H]arachidonic acid (210 Ci/mmol; 777.0 × 1010 Bq) were prepared as described. Agonist stimulation was for 1 minute after which cells were mixed with a 3-mL mixture consisting of chloroform/methanol (1:2, vol/vol). The phases were broken by the addition of 1 mL PBS and 1 mL chloroform. The lipids were extracted and samples were centrifuged at 2000g for 3 minutes and the lower chloroform phase was removed and dried down under a stream of nitrogen. The dried lipids were dissolved in a small volume of chloroform/methanol (95:5, vol/vol). The [3H]1,2-diacylglycerol (DAG) was separated by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on plastic-backed silica gel 60 plates with chloroform/methanol/acetic acid (60:40:1) as described by Bell et al.16 Unlabelled standards for monoglycerides, diglycerides, and triglycerides were run together with the samples. The lipid spots were located by exposure to iodine vapor and those corresponding to 1,2-DAG were scraped off and radioactivity measured.

Measurement of intracellular calcium

Measurement of cAMP levels

Washed platelets (200 μL/3 × 108/mL) pretreated with 3-iosobutyl-1-methylxanthine (1 mM) for 10 minutes at 37°C were subsequently incubated with forskolin (50 μM) or platelet agonists for an additional 10 minutes. Incubations were terminated with 300 μL ice-cold ethanol. The samples were centrifuged at 200g for 15 minutes and the supernatants dried under a stream of nitrogen. The cAMP levels were measured using the Amersham Biotrak enzyme immunoassay kit.

Measurement of [3H]2-MeSADP binding to platelets

[3H]2-MeSADP binding to washed platelets was determined by a rapid filtration assay as described by Jantzen et al.18 Briefly, washed platelets were resuspended in pH 7.4 HEPES-Tyrode buffer containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Platelets (2 × 108) were incubated with 50 nM [3H]2-MeSADP for 10 minutes at room temperature and the reactions terminated by addition of ice-cold pH 7.4 buffer containing 10 mM HEPES and 138 mM and filtration through glass fiber filters, followed by 3 washes. Nonspecific binding was measured in the presence of 500 μM unlabeled 2-MeSADP. Specific binding was determined by subtraction of nonspecific from total binding.

Preparation of platelet membranes

Platelet membranes were essentially prepared in the same way as described previously by Gabetta et al.9 Briefly, washed platelets were centrifuged for 10 minutes at 900g to obtain a platelet pellet followed by their resuspension in TEA buffer, pH 7.4 (10 mM triethanolamine, 5 mM EDTA, 1.8 mM EGTA [ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid], and protease inhibitor cocktail). The suspension was lysed by sonication on ice and the suspension washed in excess TEA buffer and centrifuged at 40 000g for 45 minutes at 4°C. The pellet was suspended to a concentration of approximately 1 to 2 mg/mL in TEA buffer.

Immunoblotting

Following SDS-PAGE of proteins and electrotransfer to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes, the Gαi family members were detected using isotype-specific polyclonal antibodies by immunoblotting and chemiluminescence detection.

Platelet RT-PCR and genomic sequencing of the Gαi1, Gαi2, and Gαz isotyopes

Total RNA (5 μg) extracted from washed platelets using the Qiagen RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Crawley, United Kingdom) was used for reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using the Qiagen One-Step RT-PCR system. Exon-spanning primers were selected so that splice variants resulting from exon skipping or splicing could be detected. gDNA was extracted from whole blood using the Puregene DNA isolation kit (Flowgen, Ashby, United Kingdom). Exon-flanking PCR primers were used to amplify all 8 Gαi1 and Gαi2 and both Gαz exons, using the Qiagen Hotstart Taq Master mix kit. All amplified PCR products after clean up were directly sequenced with the Big Dye Terminator Ready Reaction mix (PE Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom) and run on an ABI-310 genetic Analyzer (PE Biosystems).

Results

Platelet aggregation and [14C]5-HT secretion studies

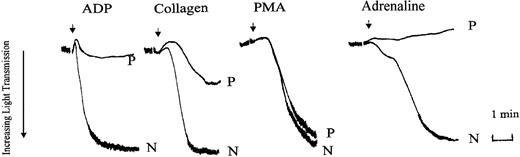

We initially compared platelet aggregation responses in PRP prepared from normal (N) and patient (P) blood. Aggregation tracings from a representative experiment are shown in Figure 1. Aggregation responses to maximal concentrations of ADP (10 μM), adrenaline (5 μM), and low-dose of collagen (2 μg/mL) were all inhibited in the patient PRP. With ADP and adrenaline this was usually accompanied by the absence of detectable primary wave aggregation. In comparison, aggregation responses to the nonreceptor operating agonist, PMA, were normal. In washed platelets, prelabeled with [14C]5-HT, aggregation and secretion responses to the weak agonists, ADP, low-dose collagen, and U46619, were impaired (Table 1). Aggregation responses were inhibited both in terms of initial rate and maximal extent of the final response (maximal aggregation). Maximal aggregation and secretion responses were seen with the strong agonist thrombin (0.05-0.2 U/mL), high-dose collagen (20 μg/mL), and PMA (100 nM), indicating that there was no inherent defect in the ability to secrete dense granule contents. However, the initial rates of aggregation with all these agonists, apart from PMA, were also markedly reduced (by approximately 50%). These observations of the aggregation responses suggested that the defect in the patient's responses lay in the signaling pathways associated with αIIbβ3 activation. Therefore, we tested the activation status of this receptor by measuring the binding of FITC-labeled fibrinogen and the ligand mimetic MoAb PAC-1 to the patient's platelets. Measurement of FITC-conjugated PAC-1 and fibrinogen in platelets stimulated with ADP, thrombin, or PMA is shown in Figure 2. In these experiments PAC-1 and fibrinogen binding to the patient's platelets was severely reduced following ADP stimulation, whereas normal levels of binding were observed following stimulation with thrombin or PMA. These results confirm that the reduced aggregation responses observed with the patient's platelets are due to defective signaling mechanisms associated with αIIbβ3 activation following stimulation by weak agonists.

Agonist-induced platelet aggregation in PRP prepared from normal (N) or patient (P) blood. Platelet aggregation was measured in an aggregometer (dual channel from Chrono-Log) and aggregation was indicated by an increase in light transmittance. Aggregation responses to ADP (10 μM), collagen (2 μg/mL), PMA (100 nM), and adrenaline (5 μM) were examined. The tracings shown are from an experiment representative of 3 others with essentially similar results. Arrows indicate points of agonist addition.

Agonist-induced platelet aggregation in PRP prepared from normal (N) or patient (P) blood. Platelet aggregation was measured in an aggregometer (dual channel from Chrono-Log) and aggregation was indicated by an increase in light transmittance. Aggregation responses to ADP (10 μM), collagen (2 μg/mL), PMA (100 nM), and adrenaline (5 μM) were examined. The tracings shown are from an experiment representative of 3 others with essentially similar results. Arrows indicate points of agonist addition.

Agonist-induced [14C]5-HT secretion and aggregation in washed platelets prepared from normal and patient blood

. | [14C]5-HT secretion, % of total cpm . | . | % maximum aggregation . | . | Initial rate of aggregation, arbitrary units . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agonist . | N . | P . | N . | P . | N . | P . | |||

| 10 μM ADP | 2 | 0 | 54 | 2 | 31 | 2 | |||

| 2 μg/mL collagen | 44 | 6 | 73 | 12 | 29 | 6 | |||

| 20 μg/mL collagen | 65 | 57 | 78 | 68 | 30 | 18 | |||

| 0.05 U/mL thrombin | 71 | 71 | 68 | 81 | 35 | 14 | |||

| 0.2 U/mL thrombin | 78 | 76 | 76 | 71 | 30 | 14 | |||

| 3 μM U46619 | 7 | 0 | 15 | 8 | 15 | 4 | |||

| 100 nM PMA | 12 | 10 | 42 | 39 | 15 | 15 | |||

. | [14C]5-HT secretion, % of total cpm . | . | % maximum aggregation . | . | Initial rate of aggregation, arbitrary units . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agonist . | N . | P . | N . | P . | N . | P . | |||

| 10 μM ADP | 2 | 0 | 54 | 2 | 31 | 2 | |||

| 2 μg/mL collagen | 44 | 6 | 73 | 12 | 29 | 6 | |||

| 20 μg/mL collagen | 65 | 57 | 78 | 68 | 30 | 18 | |||

| 0.05 U/mL thrombin | 71 | 71 | 68 | 81 | 35 | 14 | |||

| 0.2 U/mL thrombin | 78 | 76 | 76 | 71 | 30 | 14 | |||

| 3 μM U46619 | 7 | 0 | 15 | 8 | 15 | 4 | |||

| 100 nM PMA | 12 | 10 | 42 | 39 | 15 | 15 | |||

Washed platelets labeled with [14C]5-HT were prepared as described in “Patient, materials, and methods.” Platelets were incubated with agonists for 3 minutes followed by measurement of aggregation and percent [14C]5-HT secretion. With secretion studies, release from unstimulated platelets was corrected from subsequent values. The results are expressed as a percent of total counts per minute incorporated. Aggregation was measured as maximum percent light transmission change relative to platelets in resuspension buffer (RSB) versus RSB alone. Initial rate of aggregation was calculated from the initial slope of the light transmittance change versus time and expressed as arbitary units. The values shown are the averages from 2 separate experiments.

MoAb PAC-1 and fibrinogen binding to ADP-, thrombin-, or PMA-stimulated washed platelets. Washed platelets prepared from control (□) or patient blood (▪) were activated with either thrombin (0.2 U/mL; panel A), PMA (100 nM; panel B), or ADP (10 μM; panel C) in the presence of FITC-conjugated MoAb PAC-1 and FITC-labeled fibrinogen (Fg) for 60 minutes and binding assessed by flow cytometry. Results are shown as median fluorescence ± SEM obtained from quadruplicate determinations from 1 experiment representative of 2 performed.

MoAb PAC-1 and fibrinogen binding to ADP-, thrombin-, or PMA-stimulated washed platelets. Washed platelets prepared from control (□) or patient blood (▪) were activated with either thrombin (0.2 U/mL; panel A), PMA (100 nM; panel B), or ADP (10 μM; panel C) in the presence of FITC-conjugated MoAb PAC-1 and FITC-labeled fibrinogen (Fg) for 60 minutes and binding assessed by flow cytometry. Results are shown as median fluorescence ± SEM obtained from quadruplicate determinations from 1 experiment representative of 2 performed.

Agonist-induced [3H]arachidonate release and TxB2 generation

The concentrations of thrombin (0.2 U/mL) and collagen (20 μg/mL) used were shown earlier (Table 1) to maximally stimulate platelet aggregation and dense granule secretion. Addition of thrombin or collagen resulted in the maximal TxB2 generation in both normal and patient platelets (Table 2). In experiments measuring arachidonate release, similar levels were seen when comparing responses from normal and patient platelets (Table 2). These results indicate that arachidonate release from membrane phospholipid and its subsequent metabolism via cyclooxygenase pathway to TxA2 occurred normally.

Agonist-induced [3H]arachidonate release and TxB2 generation in washed platelets prepared from normal and patient blood

. | [3H]arachidonate release, % of total cpm . | . | TxB2, ng/108 platelets . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agonist . | N . | P . | N . | P . | ||

| Resting | 2.56 | 2.24 | 0.45 | 0.35 | ||

| 0.2 U/mL thrombin | 14.21 | 13.46 | 65 | 73 | ||

| 20 μg/mL collagen | 11.21 | 12.15 | 75 | 73 | ||

. | [3H]arachidonate release, % of total cpm . | . | TxB2, ng/108 platelets . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agonist . | N . | P . | N . | P . | ||

| Resting | 2.56 | 2.24 | 0.45 | 0.35 | ||

| 0.2 U/mL thrombin | 14.21 | 13.46 | 65 | 73 | ||

| 20 μg/mL collagen | 11.21 | 12.15 | 75 | 73 | ||

Washed platelets were either labeled with [3H]arachidonic acid or left unlabeled for TxB2 studies, as described in “Patient, materials, and methods.” All values were measured 3 minutes after agonist addition. TxB2 released into the supernatant was measured using a TxB2 enzyme immunoassay kit from Amersham Life Science. The values shown are the averages from 2 separate experiments.

Agonist-induced [Ca2+]i mobilization, [3H]DAG generation, and [32P]47-kDa phosphorylation

In contrast to physiologic agonists, aggregation responses stimulated by the nonphysiologic agonist PMA were unaffected. PMA is known to act as a DAG mimetic, and unlike physiologic agonists, does not stimulate PLC activation.19 Therefore, we examined the ability of different physiologic agonists to stimulate DAG production, calcium mobilization, and PKC activation, because these events are believed to be important for the activation of αIIbβ3. Agonist-induced [Ca2+]i mobilization was examined in platelets preloaded with fura-2. In studies with ADP (10 μM), 1 mM EGTA was added to the platelets prior to agonist addition to assess [Ca2+]i mobilization from exclusively intracellular pools. In these studies no differences were observed in the [Ca2+]i levels between normal and patient platelets (Table 3). Moreover, if calcium (1 mM) was added to the platelets (in the absence of EGTA), mobilization of calcium from both intracellular and extracellular sources remained unaffected (not shown). Addition of thrombin (0.2 U/mL) resulted in a more substantial increase in [Ca2+]i levels (5- to 6-fold over resting levels) in both normal and patient platelets with no differences in the levels of [Ca2+]i mobilized (Table 3). [3H]-DAG generation was assessed in platelets prelabeled with [3H]-arachidonate as most of this label is incorporated into phosphatidylinositol.20 DAG generation following PLC-mediated phosphatidylinositol 4,5,-bisphosphate breakdown occurs rapidly, peaking within 30 to 60 seconds in thrombin-stimulated platelets20,21 (results not shown). We therefore examined [3H]-DAG generation following a 1-minute incubation with thrombin and the results obtained indicate that peak DAG generation was unaffected in the patient's platelets (Table 3). PKC activation was assessed by measuring pleckstrin (47 kDa) phosphorylation in [32P]-labeled platelets. Pleckstrin phosphorylation is a commonly measured parameter to indicate PKC activation in platelets.15,22 Phosphorylation of pleckstrin was examined in platelets following a 3-minute addition of thrombin (0.2 U mL), collagen (10 μg/mL), U46619 (3 μM), or PMA (100 nM) and the results are summarized in Table 3. Phosphorylation of this substrate in response to all the agonists examined was unaffected in the patient's platelets. These results indicate that the signal transduction pathways leading to the stimulation of PKC, namely, DAG generation and calcium mobilization, in the patient's platelets were normal.

Agonist-induced [3H]-DAG generation, [Ca2+]i mobilization, and pleckstrin phosphorylation in washed platelets

. | [3H]DAG, cpm increase over resting . | . | [Ca2+]i nM, maximum above resting values . | . | [32P]47-kDa phosphorylation, cpm increase over resting . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agonist . | N . | P . | N . | P . | N . | P . | |||

| 10 μM ADP | — | — | 132 ± 5 | 133 ± 4 | — | — | |||

| 0.2 U/mL thrombin | 2430 ± 308 | 2237 ± 260 | 598 ± 6 | 552 ± 8 | 7889 | 8379 | |||

| 10 μg/mL collagen | — | — | — | — | 4032 | 3828 | |||

| 3 μM U46619 | — | — | — | — | 3940 | 3700 | |||

| 100 nM PMA | — | — | — | — | 5227 | 5439 | |||

. | [3H]DAG, cpm increase over resting . | . | [Ca2+]i nM, maximum above resting values . | . | [32P]47-kDa phosphorylation, cpm increase over resting . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agonist . | N . | P . | N . | P . | N . | P . | |||

| 10 μM ADP | — | — | 132 ± 5 | 133 ± 4 | — | — | |||

| 0.2 U/mL thrombin | 2430 ± 308 | 2237 ± 260 | 598 ± 6 | 552 ± 8 | 7889 | 8379 | |||

| 10 μg/mL collagen | — | — | — | — | 4032 | 3828 | |||

| 3 μM U46619 | — | — | — | — | 3940 | 3700 | |||

| 100 nM PMA | — | — | — | — | 5227 | 5439 | |||

Washed platelets prepared from normal/healthy (N) subjects or from the patients (P) were preloaded with either [3H]arachidonic acid (1 μCi/mL [0.037 MBq] for DAG measurements), fura-2 (2 μM for calcium measurements) or [32P]PO4 (1 mCi/mL [37 MBq] for pleckstrin phosphorylation studies) were prepared as described in “Patient, materials, and methods.” For DAG studies, thrombin incubation was for 1 minute and lipids were extracted, followed by separation of neutral lipids using TLC. The separated DAG was identified using appropriate markers and was visualized with iodine before being cut out and analyzed for radioactivity. In phosphorylation studies, agonist stimulation was for 3 minutes. Following electrophoretic separation of [32P]-labeled proteins, areas on the gel corresponding to the 47-kDa protein (pleckstrin) were cut out and analyzed for associated radioactivity. For 47-kDa phosphorylation measurements the values shown are the averages from 2 separate experiments. The values shown for DAG and calcium measurements are mean values ± SEM (n = 3). — indicates not done.

cAMP levels in forskolin-treated platelets stimulated with thrombin, ADP, or adrenaline and measurement of [3H]-2MeSADP binding in resting platelets

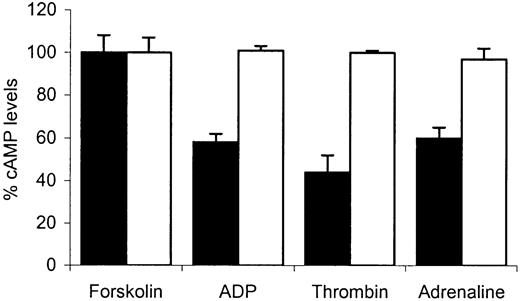

We next examined the ability of different platelet agonists to suppress forskolin-induced elevation of intracellular cAMP. Thrombin, high-dose adrenaline, and ADP are believed to suppress this increase by inhibiting adenylate cyclase through predominantly Gαi2- or Gαz-mediated mechanisms.23-25,29 Initially we compared basal cAMP levels in the patient platelets versus normal platelets and these experiments revealed them to be similar (1.51 ± 0.07 nmol/1011 platelets versus 1.47 ± 0.07 nmol/1011 platelets). The addition of forskolin (50 μM) resulted in a similar increase in the intracellular levels of cAMP levels in control or patient platelets (96 ± 14 nmol/1011 platelets versus 92 ± 14 nmol/1011 platelets).

Figure 3 shows the percent cAMP levels (expressed relative to forskolin-stimulated response at 100%) in platelets treated with forskolin alone and in platelets pretreated with forskolin (50 μM) followed by addition of thrombin (0.2 U/mL), ADP (10 μm), or adrenaline (10 μM). In normal platelets the addition of thrombin, ADP, or adrenaline resulted in a marked suppression of this increase. ADP and adrenaline suppressed forskolin-induced cAMP. In comparison, with patient platelets no suppression was seen with any of the agonists used. Our observation that Gαi-mediated inhibition of adenylate cyclase was abnormal in response to 3 distinct receptor-operating agonists indicates that the defect in the patient's platelets was more likely to be at the level of Gαi itself and not due to abnormal receptor function. This was confirmed in studies where total binding of the ADP analog, [3H]2-MeSADP was measured in washed platelets. Similar levels of binding were found in patient platelets compared with normal platelets (Figure 4).

The effect of ADP, thrombin, or adrenaline on forskolin-stimulated cyclic AMP accumulation. Washed platelets prepared from normal (▪) or patient (□) blood were preincubated with 0.5 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) for 10 minutes followed by an additional 10-minute incubation with 50 μM forskolin alone or with either ADP (10 μM), thrombin (0.2 U/mL), or adrenaline (10 μM). At the end of the final incubation, cAMP was extracted and the levels determined by immunoassay, as described in “Patient, materials, and methods.” Control values were obtained from forskolin-stimulated platelets and the results following agonist stimulation are expressed as percentages of these control values. Data values are mean ± SEM from triplicate determinations from 3 separate experiments.

The effect of ADP, thrombin, or adrenaline on forskolin-stimulated cyclic AMP accumulation. Washed platelets prepared from normal (▪) or patient (□) blood were preincubated with 0.5 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) for 10 minutes followed by an additional 10-minute incubation with 50 μM forskolin alone or with either ADP (10 μM), thrombin (0.2 U/mL), or adrenaline (10 μM). At the end of the final incubation, cAMP was extracted and the levels determined by immunoassay, as described in “Patient, materials, and methods.” Control values were obtained from forskolin-stimulated platelets and the results following agonist stimulation are expressed as percentages of these control values. Data values are mean ± SEM from triplicate determinations from 3 separate experiments.

Total binding of [3H]2-MeSADP to washed platelets prepared from patient and normal blood. Binding of [3H]2-MeSADP to washed platelets was measured as described in “Patient, materials, and methods.” Specific binding was assessed in the presence of 500 μM unlabeled 2-MeSADP. Nonspecific binding values were subtracted from values obtained from total binding and these corrected values are represented as specific counts per minute (cpm). Data values are mean ± SEM from quadruplicate determinations from 1 experiment representative of 2 performed.

Total binding of [3H]2-MeSADP to washed platelets prepared from patient and normal blood. Binding of [3H]2-MeSADP to washed platelets was measured as described in “Patient, materials, and methods.” Specific binding was assessed in the presence of 500 μM unlabeled 2-MeSADP. Nonspecific binding values were subtracted from values obtained from total binding and these corrected values are represented as specific counts per minute (cpm). Data values are mean ± SEM from quadruplicate determinations from 1 experiment representative of 2 performed.

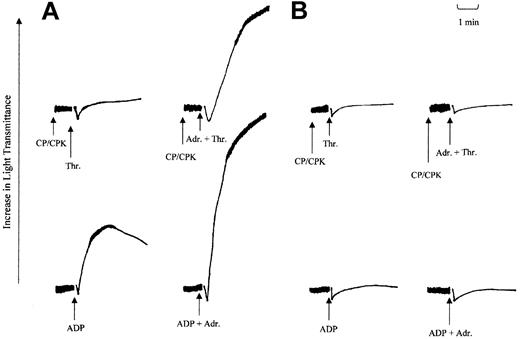

The effect of adrenaline on aggregation responses stimulated by ADP or low-dose thrombin in washed platelets

The loss in the ability of either ADP or adrenaline to mediate Gi signaling was investigated further in a series of platelet aggregation studies. In these studies the ability of adrenaline to potentiate aggregation responses induced by ADP or low-dose thrombin was investigated and the results are shown in Figure 5. In washed platelets, adrenaline fails to stimulate platelet aggregation on its own. However, in combination with agonists that signal through Gq-coupled receptors, such as ADP, thrombin, or TxA2, adrenaline can potentiate the aggregation responses induced by these agonists. Adrenaline is believed to do this by supplementing Gi signaling induced by ADP through its P2Y12 receptor or totally providing this component for TxA2.3,13,26 Therefore, we examined this ability of adrenaline in aggregation responses stimulated by ADP (5 μM) and thrombin (0.025 U/mL). As shown earlier with the patient's platelets, ADP fails to stimulate aggregation responses at maximal concentrations (10 μM and above). In comparison, in normal platelets, ADP at a lower dose (5 μM) induces primary aggregation (Figure 5A). The addition of adrenaline (3 μM) prior to ADP (5 μM) addition produced irreversible maximal secondary aggregation. In comparison, with the patient's platelets, only shape change was detected (Figure 5B). This finding suggests that the defect in ADP-induced aggregation cannot be corrected by coaddition with adrenaline. This observation is significant considering that ADP-induced calcium mobilization was normal in the patient's platelets, indicating a normal activation of Gq-coupled pathways. The inability of adrenaline to correct the aggregation response suggests that Gi activation in response to both these agonists was affected. This loss in the ability of adrenaline to potentiate platelet aggregation was confirmed in studies using low-dose thrombin. In these studies creatinine phosphate (40 mM) and creatinine phosphokinase (100 U/mL) were added 1 minute prior to agonist addition to remove any effect of either residual or secreted ADP on the aggregation responses. In normal platelets, adrenaline strongly potentiated the thrombin-induced aggregation response (Figure 5A), whereas, in comparison, patient platelets were completely unresponsive to adrenaline treatment (Figure 5B). These observations are consistent with the notion that there was a reduction in the ability of either adrenaline or ADP, when acting through their respective receptors, to effectively mediate Gαi activation.

Effect of adrenaline on thrombin and ADP-induced aggregation. The effect of adrenaline on ADP- and thrombin-induced aggregation in washed platelets prepared from normal (A) or patient (B) blood. Washed platelets were incubated with adrenaline (3 μM) or saline just prior to the addition of either ADP (5 μM) or thrombin (0.025 U/mL). In experiments with thrombin, a combination of creatinine phosphate (CP; 40 mM) and creatine phosphokinase (CPK; 100 U/mL) was added 1 minute prior to agonist addition. Arrows indicate points of induction. The results shown are representative of 2 other independent experiments.

Effect of adrenaline on thrombin and ADP-induced aggregation. The effect of adrenaline on ADP- and thrombin-induced aggregation in washed platelets prepared from normal (A) or patient (B) blood. Washed platelets were incubated with adrenaline (3 μM) or saline just prior to the addition of either ADP (5 μM) or thrombin (0.025 U/mL). In experiments with thrombin, a combination of creatinine phosphate (CP; 40 mM) and creatine phosphokinase (CPK; 100 U/mL) was added 1 minute prior to agonist addition. Arrows indicate points of induction. The results shown are representative of 2 other independent experiments.

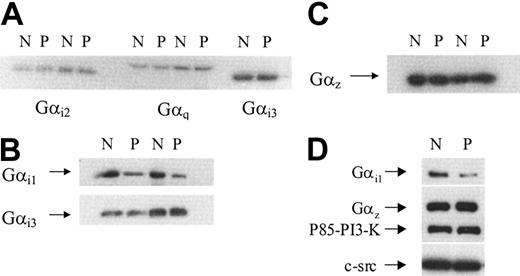

The expression of Gαi1,Gαi2,Gαi3, Gαz, and Gαq subunits in platelet membranes and peripheral blood monocytes

Human platelets contain 4 members of the Gαi subfamily: Gαi1, Gαi2, Gαi3, and Gz.27,28 Because these subfamily members can all inhibit cAMP formation by adenylate cyclase, we examined the levels of expression of these different subtypes in membranes prepared from normal and patient platelets. Immunoblots were probed with specific antisera against Gαi1, Gαi2, Gαi3, and Gαz. Additionally, the blots were also probed with specific antisera against Gαq. Autoradiographs from representative experiments are shown in Figure 6. The levels of Gαi2, Gαi3, Gαq (Figure 6A), and Gαz (Figure 6C) detected in patient samples were similar to those found in normal samples. In comparison, a striking difference was found when examining Gαi1 levels (Figure 6B). A substantial decrease in immunoreactivity against Gαi1 was found in membranes prepared from the patient. When the bands corresponding to Gαi1 were analyzed by densitometry, the average (from 3 separate membrane preparations) decrease in its expression was approximately 75%. We confirmed that this reduction in Gαi1 was genuine by probing membrane samples with a different rabbit polyclonal antibody, raised essentially against the same sequence, and the results are shown in Figure 6D. A similar reduction in levels of Gαi1 was observed; moreover, this blot was stripped and probed with an anti-Gαz antibody to confirm its levels were unchanged. Equal loading of samples was further confirmed by probing the same blot with anti P85 PI-3K and anti c-Src antibodies.

Immunodetection of Gαi1, Gαi2, Gαi3, Gαz, and Gαq in membranes prepared from normal or patient platelets. Platelet membranes were prepared from normal (N) or patient (P) blood as described in “Patient, materials, and methods.” Protein (40 μg) was loaded onto a 10% gel and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes by electroblotting and probed with specific antisera against different Gα subunits. (A) Gαi2 and Gαq detected in platelet membranes from 2 separate experiments and Gαi3 detected in platelet membranes from a single preparation. (B) Gαi1 detected in 2 separate membrane preparations prepared during 2 separate visits. This blot was stripped and reprobed with anti Gαi3 as a loading control. (C) Gαz detected in 2 separate membrane preparations prepared from 2 separate visits. (D) Gαi1 detected by a second anti-Gαi1 antibody (AB-2). The blot was stripped 3 times and successively probed with anti Gαz, p85 PI-3K, and c-Src antibodies, respectively.

Immunodetection of Gαi1, Gαi2, Gαi3, Gαz, and Gαq in membranes prepared from normal or patient platelets. Platelet membranes were prepared from normal (N) or patient (P) blood as described in “Patient, materials, and methods.” Protein (40 μg) was loaded onto a 10% gel and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes by electroblotting and probed with specific antisera against different Gα subunits. (A) Gαi2 and Gαq detected in platelet membranes from 2 separate experiments and Gαi3 detected in platelet membranes from a single preparation. (B) Gαi1 detected in 2 separate membrane preparations prepared during 2 separate visits. This blot was stripped and reprobed with anti Gαi3 as a loading control. (C) Gαz detected in 2 separate membrane preparations prepared from 2 separate visits. (D) Gαi1 detected by a second anti-Gαi1 antibody (AB-2). The blot was stripped 3 times and successively probed with anti Gαz, p85 PI-3K, and c-Src antibodies, respectively.

Gαi cDNA sequence analysis

To establish a possible genetic basis for the reduced levels of the Gαi1 proteins observed in the patient's platelet membranes, we carried out RT-PCR and sequencing on platelet cDNA, as well as screening for mutations in all 8 Gαi1 exons by direct PCR sequencing. Our results revealed no mutations or variant transcripts apart from the expected PCR product (results not shown). Studies in Gαi2 and Gαz knockout mice have shown these proteins play an important role in modulating ADP- and adrenaline-induced platelet aggregation, respectively.25,29 We therefore examined platelet Gαi2 cDNA and the coding genomic sequences of both Gαi2 and Gαz. Gαi2 was found to be normal at both the gDNA and cDNA levels. In comparison, genomic sequencing of Gαz revealed the presence of common neutral single nucleotide polymorphism (321C>T; genotype frequency 0.25) associated with exon 1 on this gene (NCBI SNP: SS3177457).

Discussion

We have characterized platelet functional responses and signaling pathways in a patient suffering from a chronic bleeding disorder. These studies revealed severely reduced aggregation responses to weak agonists such as ADP and adrenaline, whereas responses to high-dose thrombin or collagen were largely unaffected. Several lines of evidence are consistent with the conclusion that the impaired aggregation observed may be due to defective activation of Gi-coupled pathways and that the defect may be at the level of Gαi receptor coupling. (1) The ability of multiple agonists with Gi-coupled receptors (ADP, thrombin, and adrenaline) to suppress cAMP levels in platelets treated with forskolin was inhibited, indicating dysfunctional Gαi coupling. (2) Activation of Gq-coupled pathways in response to thrombin, ADP, or TxA2 was normal. (3) Aggregation responses induced by weak agonists were more severely affected than those for strong agonists such as thrombin. This is consistent with the recent studies indicating a critical role for the coactivation of both Gαi- and Gαq-coupled signaling pathways in stimulating weak agonist-induced platelet aggregation. (4) In washed platelets, the defect in ADP-induced aggregation could not be corrected by the addition of adrenaline, indicating that the function of the P2Y12 receptor, which is coupled to Gαi activation, could not be substituted by another agonist with Gi-coupled receptors.

Given the essential role played by Gq-mediated signaling pathways in promoting platelet aggregation by either strong or weak agonists,26,30 our findings indicated that activation of PLC and PKC (Table 3) occurred normally in the patient in response to agonists with Gq-coupled receptors (ADP, thrombin, and TxA2), implying that the impaired aggregation observed occurred through other mechanisms. In comparison, Gαi activation was inhibited in response to multiple agonists. Neither ADP, thrombin, nor adrenaline acting through their P2Y12, PAR-1, and α2A-adrenergic receptors, respectively, was able to suppress forskolin-induced rise in cAMP. All 3 agonists have receptors coupled to Gαi2 activation, an event required for the inhibition of adenylate cyclase.23-25,40 It is interesting to note that aggregation stimulated by high-dose thrombin was normal compared with that induced by high-dose ADP. This probably reflects their contrasting ability to activate PLC with thrombin stimulating PLC activity more strongly than ADP or indeed other agonists (Table 3).31-34 It is known that activation of this enzyme correlates well with the stimulation of platelet aggregation and secretion. Therefore, our results indicate that at least with high-dose thrombin, Gαq signaling pathways are more critical for aggregation than Gi signaling. In comparison, with ADP, although PLC activation was normal, as indicated by the mobilization of intracellular calcium (Table 3), platelet aggregation remained defective indicating the requirement for ADP-mediated Gi signaling. Our observation supports the model proposed by several workers for ADP-induced platelet aggregation requiring concomitant signaling through P2Y1 and P2Y12 receptors through the respective activation of Gq and Gi signaling pathways.3,18,35 The reduced aggregation seen in response to either low-dose collagen or TxA2 may be explained by this loss in ADP-induced signaling through the P2Y12 receptor. Its known that ADP released from dense granules plays an important role in potentiating aggregation in response to these agonists.26,36,37 Defects in Gi signaling have been reported in patients with other bleeding disorders but all these defects have been as a consequence of impaired interaction between the agonists and their receptors. Platelet functional responses have been characterized in several patients in whom interaction between ADP and the P2Y12 receptor has been abnormal mainly as a consequence of reduced P2Y12 receptor number.11-13 In these patients ADP and weak agonist-induced aggregation were severely impaired, as was the ability of ADP (not adrenaline) to suppress cAMP elevation induced by either forskolin or PGE1.11,12 Defective interaction between adrenaline and its α2A-adrenergic receptor has also been reported in the platelets of a patient suffering from a chronic bleeding disorder.38 There was a loss in the ability of adrenaline to potentiate weak agonist-induced aggregation and to suppress PGE1-induced cAMP rise but responses to ADP were normal. In our studies, aggregation responses to both ADP and adrenaline were impaired and this along with a loss in the ability of these agonists and thrombin to suppress forskolin-stimulated rise in intracellular cAMP make it highly unlikely that agonist-receptor interactions were defective. Indeed, the level of binding of [3H]2MeSADP, an ADP analog, to the patient's platelets was similar to that found in normal platelets (Figure 4). Although several types of agonist receptor defects have been reported in patients with bleeding disorders,11,12,38,39 to our knowledge multireceptor defects have not been reported thus far. Moreover, the inability of adrenaline to correct the defect in ADP-induced aggregation (Figure 5) indicates that Gi signaling through the P2Y12 receptor could not be substituted by Gi signaling through the α2A-adrenergic receptor, indicating a signaling defect downstream of receptor activation.

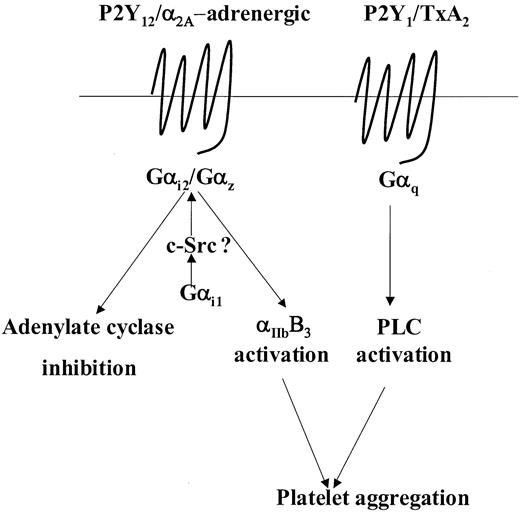

Human platelets contain several members of the Gαi family including the highly homologous Gαi1, Gαi2, and Gαi3 family members as well as the least homologous member, Gαz.27-29 Studies in knockout mice have established that Gαi2 and Gαz play a critical role in modulating adenylate cyclase activity and platelet aggregation in response to ADP and adrenaline, respectively.25,29 Moreover, at least in mice, Gαi2 and Gαz are the predominant subtypes coupled to the P2Y12 and α2A-adrenergic receptors, respectively.25,29,40,41 Examination of Gαi2 and Gαz levels in the patient's platelets indicated normal levels of expression of both these proteins. Moreover, sequencing analysis of the Gαi2 gene revealed no mutations and analysis of the Gαz gene revealed the presence of a common neutral SNP (321C>T), which has no bearing on the amino acid sequence. Therefore, our results could not be explained in the context of a loss of function of these 2 Gαi subtypes. However, we observed that expression of Gαi1 a minimally expressed species in human platelets,25,27 was markedly reduced by approximately 75%. A role for Gαi1 with regard to platelet functional responses has yet not been elucidated and studies on Gαi1 knockout mice have so far not revealed any obvious physiologic abnormalities.42 Nonetheless, the situation in mouse and human platelets with regard to the presence of Gαi1 is quite different. The apparent lack of detectable Gαi1 expression in mouse platelets25 cannot be reconciled with both our findings and those of Williams et al27 of detectable Gαi1 in human platelets. In this instance, one has to be careful to interpret its role in murine platelets as apposed to human platelets. Our results suggest that the considerable reduction in the levels of Gαi1 observed in the patient platelets accounts for the impaired responses seen following stimulation with either ADP or adrenaline. Conceptually, it is possible that Gαi1 may have a distinct but complimentary role with regard to the abilities of Gαi2 and Gαz to regulate their respective effectors. For example, Gαi1 may prime these G proteins to either effectively respond to agonist stimulation or efficiently modulate their effectors. The priming mechanism could involve tyrosine phosphorylation of both Gαi2 and Gαz inaGαi1-dependent manner. Hausdorff et al43 have shown that pp60src can phosphorylate most members of the Gαi family and that this may modulate their function. More recently, Ma et al44 have shown that Gαi1 in particular can specifically associate with and activate pp60src and in human platelets; Torti et al45 have shown that adrenaline can induce association of pp60src with an unidentified Gαi family member (possibly Gαi1). Therefore, priming by Gαi1 in such a manner could possibly modulate the ability of Gαi2 and Gαz to respond to agonist stimulation or regulate their ability to modulate their effectors as represented in a hypothetical model (Figure 7). According to this hypothetical model, despite the presence of normal levels of Gαi2 and Gαz, a severe reduction in levels of Gαi1 may have drastic effects on downstream effectors regulated by Gαi2 and Gαz. Thus, this model does not contradict the considerable evidence implicating a critical role for both Gαi2 and Gαz in modulating adenylate cyclase activity and effectors involved in promoting ADP- or adrenaline-mediated platelet aggregation.

Model depicting a putative role for Gαi1 in weak agonist-induced signal transduction. This model incorporates the model put forward by Jin and Kunapuli3 stating that coactivation of Gi- and Gq-coupled signaling pathways are necessary for weak agonist-induced platelet aggregation. For example, with ADP and adrenaline, this Gi component is provided following activation of Gαi2 and Gαz, respectively. Here we propose that following agonist receptor coupling, activation of either Gαi2 or Gαz may require priming by Gαi1, possibly in a c-Src–dependent manner, to regulate effectors such as adenylate cyclase or those involved in the activation of αIIbβ3. See “Discussion” for further details.

Model depicting a putative role for Gαi1 in weak agonist-induced signal transduction. This model incorporates the model put forward by Jin and Kunapuli3 stating that coactivation of Gi- and Gq-coupled signaling pathways are necessary for weak agonist-induced platelet aggregation. For example, with ADP and adrenaline, this Gi component is provided following activation of Gαi2 and Gαz, respectively. Here we propose that following agonist receptor coupling, activation of either Gαi2 or Gαz may require priming by Gαi1, possibly in a c-Src–dependent manner, to regulate effectors such as adenylate cyclase or those involved in the activation of αIIbβ3. See “Discussion” for further details.

The types of signaling defects reported in patients with congenital abnormalities have been growing.8 Here we report the first description of a defect at the level of Gαi dysfunction in such a patient. These studies further highlight the important role played by Gi-signaling pathways in regulating weak agonist-induced platelet aggregation. Moreover, our findings support the contention for a novel role for Gαi1 in the regulation of platelet aggregation in human platelets. Finally, our understanding of the mechanisms involved in Gαi1 activation as well as the identification of its effectors could provide important information regarding signaling pathways associated with αIIbβ3 activation.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, February 27, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3080.

Y.M.P., K.P., and S.R. contributed equally to this study.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We would like to thank Dr David Heaton for referring the patient.

![Figure 4. Total binding of [3H]2-MeSADP to washed platelets prepared from patient and normal blood. Binding of [3H]2-MeSADP to washed platelets was measured as described in “Patient, materials, and methods.” Specific binding was assessed in the presence of 500 μM unlabeled 2-MeSADP. Nonspecific binding values were subtracted from values obtained from total binding and these corrected values are represented as specific counts per minute (cpm). Data values are mean ± SEM from quadruplicate determinations from 1 experiment representative of 2 performed.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/101/12/10.1182_blood-2002-10-3080/6/m_h81234452004.jpeg?Expires=1767887785&Signature=ZQqDjKv0ASRgjC3nw4w3UNAtCKsVItjTWKNFXacri4d6X~UTNjUGKzORBTniWFkTLQKIJabbSxD5zobU9YMAWc9lNZ7Hp7rYVCyQmZd2bzdEodkTpZ4XoUfqSIclCFaUzL1VCwK8GrAHKLmUYJ42-rmWciyk0w5rL5SvAMOZNf2vx2DrShg21BDKMuLBDUp1bjCasA4RKGMcZ685avSjp0CZFzmOTMfd9q~wRzwRfsy-bjOvl1uE0bmWQ7ut7dsQXCp9K7UahtVzD-B9-Xt2uOYJ2RVQnXjCubaFDuISSgv4v~hbZTDYHII3pj8iX5uGVbgc8lb~MbXSuTvvoBzPlQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal