The mixed lineage leukemia (MLL) gene undergoes fusions with a diverse set of genes as a consequence of chromosomal translocations in acute leukemias. Two of these partner genes code for members of the forkhead subfamily of transcription factors designated FKHRL1 and AFX. We demonstrate here that MLL-FKHRL1 enhances the self-renewal of murine myeloid progenitors in vitro and induces acute myeloid leukemias in syngeneic mice. The long latency (mean = 157 days), reduced penetrance, and hematologic features of the leukemias were very similar to those observed for the forkhead fusion protein MLL-AFX and contrasted with the more aggressive features of leukemias induced by MLL-AF10. Transformation mediated by MLL-forkhead fusion proteins required 2 conserved transcriptional effector domains (CR2 and CR3), each of which alone was not sufficient to activate MLL. A synthetic fusion of MLL with FKHR, a third mammalian forkhead family member that contains both effector domains, was also capable of transforming hematopoietic progenitors in vitro. A comparable requirement for 2 distinct transcriptional effector domains was also displayed by VP16, which required its proximal minimal transactivation domain (MTD/H1) and distal H2 domain to activate the oncogenic potential of MLL. The functional importance of CR2 was further demonstrated by its ability to substitute for H2 of VP16 in domain-swapping experiments to confer oncogenic activity on MLL. Our results, based on bona fide transcription factors as partners for MLL, unequivocally establish a transcriptional effector mechanism to activate its oncogenic potential and further support a role for fusion partners in determining pathologic features of the leukemia phenotype.

Introduction

The mixed lineage leukemia(MLL) gene is a frequent target of chromosomal translocations in human leukemias.1 These result in the creation of fusion genes that encode chimeric proteins containing one of more than 30 different partners. Although the promiscuous nature of MLL fusions suggests a potential dominant-negative pathogenetic mechanism mediated by truncated MLL proteins, both in vitro2-5 and in vivo6 experimental models consistently demonstrate essential roles for the fusion partners in leukemogenesis.

FKHRL1 and AFX are 2 MLL fusion partners that have well-characterized roles in transcriptional regulation. They are members of the forkhead subfamily of transcription factors (FKHR family) that contain highly conserved forkhead DNA-binding domains (DBDs) and are major downstream targets of protein kinase B (PKB/Akt) in a conserved signaling pathway that regulates expression of cell cycle regulatory and proapoptotic genes.7-9 A third member of the forkhead subfamily, FKHR, undergoes protein fusions with members of the PAX family of transcriptional regulators following chromosomal translocations in pediatric alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas (ARMs).10-12 In both leukemias and ARMs, the site of fusion invariably occurs in the middle of the forkhead DBD, resulting in MLL or PAX chimeric proteins containing similar carboxy-terminal portions harboring transcriptional activation domains of the respective forkhead proteins. This suggests that cancers of different molecular and cellular origin may share common pathogenetic mechanisms determined by the transcriptional effector properties of the forkhead protein subfamily. The current studies were undertaken to determine the comparative features of leukemias induced by various forkhead family MLL fusion proteins and to establish their contributions to myeloid leukemogenesis.

Materials and methods

DNA constructs

Retroviral constructs were made by cloning of various FKHRL1, FKHR, Daf-16a1, AFX, and AF10 DNA fragments amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on appropriate cDNA templates into theNruI and XhoI sites of the murine stem cell virus (MSCV)–neo MLL 5′ cloning vector that encodes MLL amino acids 1-139613 as previously described.14MLL-VP16 constructs encoding the full-length (FL; amino acids 413-490), proximal minimal transactivation domain (MTD/H1, amino acids 413-453), or distal H2 domain (amino acids 453-490) of VP16 were made by PCR of appropriate DNA fragments, which were then cloned into the MSCV-neo MLL 5′ cloning vector as previously described.15 Gal4 fusion constructs consisted of various PCR fragments cloned into theBamHI site of pSG424 that encodes the Gal4 DBD (amino acids 1-147). The full-length Gal4-Daf-16a1 was reported previously.16 All constructs were sequenced to exclude mutations introduced by PCR.

Retroviral transduction and transplantation assays

Hematopoietic progenitor transformation assays were performed as previously described.15 Briefly, viral supernatants were collected 3 days after transfection of Phoenix cells and used to infect hematopoietic stem and progenitors cells (harvested from the bone marrow of 4- to 10-week-old C57BL/6 mice) that were positively selected for c-Kit expression by magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS). After spinoculation, transduced cells were then plated in 1% methylcellulose (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) supplemented with cytokines in the presence or absence of 1 mg/mL G418. After 7 days of culture, colonies were counted to calculate the transduction efficiency. Single-cell suspensions (104 cells) of G418-resistant colonies were then replated in methylcellulose medium supplemented with growth factors without G418. Plating was repeated every 7 days.

In each round of replating, single-cell suspensions were also expanded in RPMI liquid culture containing 20% fetal calf serum (FCS) plus 20% WEHI-conditioned medium. For tumorigenicity assays, 106 immortalized cells were injected into the retro-orbital venous sinus of 6-week-old syngeneic C57BL/6 mice, which had received a sublethal dose of 5.25 Gy total body γ irradiation (135Cs). Mice were maintained on antibiotic water to avoid infection and monitored for development of leukemia by complete blood count, blood smear, and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis. Tissues were fixed in buffered formalin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histologic analysis.

Phenotype analysis

Immunophenotypic analysis was performed by FACS using fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies to Sca-1 (D7 clone), c-Kit (2B8 clone), Mac-1 (M1/70 clone), Gr-1 (RB6-8C5 clone), B220 (RA3-6B2 clone), and CD19 (1D3 clone), all from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA), respectively. Staining was generally performed on ice for 15 minutes. Cells were washed twice in staining medium and resuspended in 1 μg/mL propidium iodine (PI) before analysis using a Moflops (a modified triple laser Cytomation/Becton Dickinson hybrid FACS). Dead cells were gated out by high PI staining and forward light scatter.

Expression studies

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed using MLL and fusion gene–specific primers (sequences available on request) on total RNA extracted from primary transduced bone marrow cells. Western blotting was performed on COS7 or Phoenix cells transiently transfected with various MLL constructs. Lysate proteins (30 μg) were fractionated in 5% polyacrylamide gel and transferred to enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) membranes (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) using Tris (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane)–glycine sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) transfer buffer. After blocking, membranes were probed with monoclonal antibody N4.4 directed against an MLL amino-terminal epitope as previously described.14 15

Transcriptional transactivation assays

The 293 or COS7 cells (5 × 104) were seeded overnight in 24-well plates before transfection using Fugene 6 (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN). Then, 0.2 μg Gal4-DBD fusion construct was cotransfected with 0.1 μg pcDNA3.1/LacZ internal control plasmid and 0.2 μg luciferase reporter construct, which contained 2 tandem copies of Gal4 consensus-binding sites and the luciferase gene driven by herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV-TK), adenovirus E1b, or the myelomonocytic growth factor promoters.17 Luciferase activities were normalized based on β-galactosidase levels. Means and SDs were determined from at least 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate.

Results

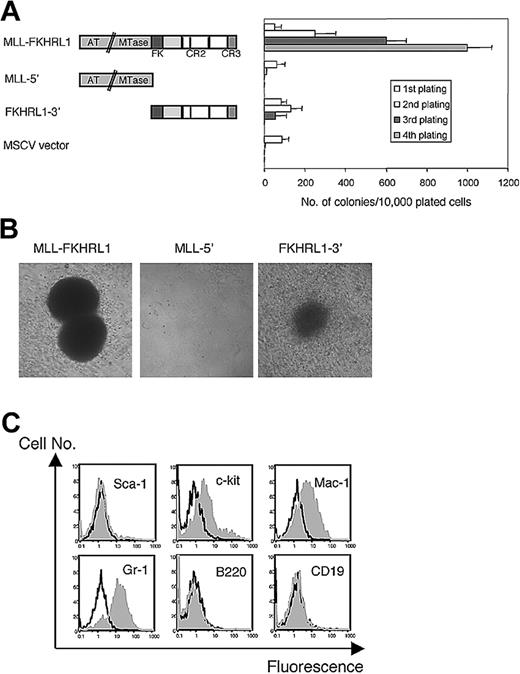

MLL-FKHRL1 enhances the self-renewal of murine myeloid progenitors in vitro

Primary murine hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells were transduced with recombinant retroviruses encoding MLL-FKHRL1 or the respective portions of MLL (5′-MLL) and FKHRL1 (3′-FKHRL1). Initial plating of transduced cells in methylcellulose yielded similar numbers, size, and morphology of colonies for each of the constructs, indicating comparable transduction efficiencies (Figure1A). The expression of each construct was confirmed by Western blot of transfected Phoenix cells (data not shown). Cells transduced with MLL-FKHRL1 showed enhanced growth potential as evidenced by continued ability to generate colonies on serial replating in methylcellulose culture. Conversely, cells transduced with 5′-MLL, 3′-FKHRL1, or vector alone exhausted their growth potential after the second or third plating. MLL-FKHRL1–transduced cells grew as compact, immature granulocyte-erythrocyte-macrophage-megakaryocyte colony-forming unit (CFU-GEMM)–like colonies (Figure 1B) and expressed c-kit, Mac-1, and Gr-1 but were negative for stem cell (Sca-1), lymphoid (B220, CD19, CD3), and erythroid (Ter119) markers, indicating an origin from myeloid progenitors (Figure 1C and data not shown). These cells rapidly expanded and grew indefinitely in liquid culture supplemented with interleukin 3 (IL-3) demonstrating that MLL-FKHRL1 immortalizes myeloid progenitors in vitro.

Forced expression of MLL-FKHRL1 immortalizes murine myeloid progenitors.

(A) Schematic diagram of MLL-FKHRL1 and the retroviral constructs used in transduction/transplantation assays (left). Conserved motifs in MLL-FKHRL1 include the DNA methyltransferase homology region (MTase), AT hook DBD (AT hook), forkhead DBD (FK), conserved region 2 (CR2), which contains 3 α helices shown as thin vertical bars, and conserved region 3 (CR3). Bar graph (right) shows numbers of colonies obtained after each round of plating in methylcellulose (average of 3 independent assays). (B) Typical morphology of colonies generated at third plating of bone marrow cells transduced with retroviruses expressing the indicated constructs (original magnification, × 100). (C) Phenotypic analysis of cells immortalized by MLL-FKHRL1. Gray histograms represent FACS staining obtained with antibodies specific for the indicated cell surface antigens. Black lines represent staining obtained with isotype control antibodies.

Forced expression of MLL-FKHRL1 immortalizes murine myeloid progenitors.

(A) Schematic diagram of MLL-FKHRL1 and the retroviral constructs used in transduction/transplantation assays (left). Conserved motifs in MLL-FKHRL1 include the DNA methyltransferase homology region (MTase), AT hook DBD (AT hook), forkhead DBD (FK), conserved region 2 (CR2), which contains 3 α helices shown as thin vertical bars, and conserved region 3 (CR3). Bar graph (right) shows numbers of colonies obtained after each round of plating in methylcellulose (average of 3 independent assays). (B) Typical morphology of colonies generated at third plating of bone marrow cells transduced with retroviruses expressing the indicated constructs (original magnification, × 100). (C) Phenotypic analysis of cells immortalized by MLL-FKHRL1. Gray histograms represent FACS staining obtained with antibodies specific for the indicated cell surface antigens. Black lines represent staining obtained with isotype control antibodies.

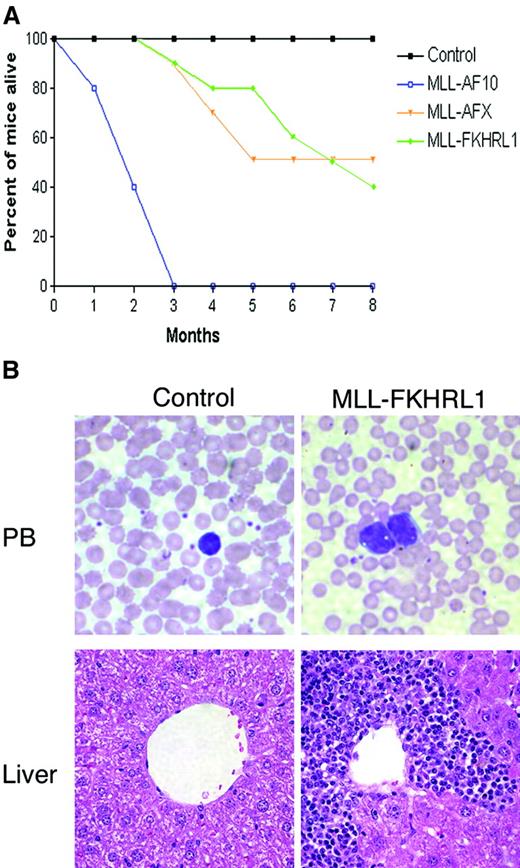

MLL-FKHRL1–transduced cells induce leukemias with long latencies

The leukemogenic potential of progenitors immortalized by MLL-FKHRL1 was tested in sublethally irradiated, syngeneic C57BL/6 mice (106 cells injected intravenously). Half of the MLL-FKHRL1 cohort died of acute leukemias within 7 months (Figure2A). Histologic and cytologic analyses revealed the presence of leukemic blasts in the bone marrow and peripheral blood, as well as leukemic infiltration along the periportal zones in the livers of moribund mice (Figure 2B). The leukemic blasts displayed an early myeloid phenotype identical to the injected cells (data not shown). The mean latency period for development of MLL-FKHRL1 leukemias was 157 days, which is very similar to that determined previously15 for the forkhead fusion protein MLL-AFX (mean = 185 days) under identical experimental conditions (Figure2A). The long latencies and reduced penetrance for development of leukemias by both MLL-forkhead fusion proteins, however, contrasted with the short latency (mean = 52 days) and high penetrance (100%) of murine leukemias induced by MLL-AF10 (Figure 2A and DiMartino et al18). Furthermore, peripheral blood cell numbers were markedly lower (11 versus 220 million/mL) with fewer circulating blasts and less extensive extramedullary organ involvement (liver and spleen) in the MLL-forkhead protein leukemias (Table1). Thus, MLL-FKHRL1 induces acute leukemias with myeloid progenitor phenotypes in vivo, but their relatively less aggressive character suggests a role for forkhead subfamily partners in determining specific aspects of leukemia pathology.

MLL-FKHRL1–immortalized cells induce acute leukemias with latencies similar to MLL-AFX.

(A) Survival curves are shown for cohorts (n = 10) of sublethally irradiated C57BL/6 mice that were injected with MLL-FKHRL1–, MLL-AFX–, or MLL-AF10–immortalized cells or saline injected (control) mice. Differences in survival were statistically significant for MLL-FKHRL1 compared to control (P < .018) and MLL-AF10 (P < .008) cohorts but not for MLL-AFX cohort (P < .299). (B) Representative histology is shown for control and MLL-FKHRL1 mice. Leukemic blasts are present in the peripheral blood and infiltrate the portal veins of liver of moribund MLL-FKHRL1 mice (original magnification, × 400). Blood smears were stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa; paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (original magnification, × 200).

MLL-FKHRL1–immortalized cells induce acute leukemias with latencies similar to MLL-AFX.

(A) Survival curves are shown for cohorts (n = 10) of sublethally irradiated C57BL/6 mice that were injected with MLL-FKHRL1–, MLL-AFX–, or MLL-AF10–immortalized cells or saline injected (control) mice. Differences in survival were statistically significant for MLL-FKHRL1 compared to control (P < .018) and MLL-AF10 (P < .008) cohorts but not for MLL-AFX cohort (P < .299). (B) Representative histology is shown for control and MLL-FKHRL1 mice. Leukemic blasts are present in the peripheral blood and infiltrate the portal veins of liver of moribund MLL-FKHRL1 mice (original magnification, × 400). Blood smears were stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa; paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (original magnification, × 200).

Characteristics of leukemias induced by MLL fusion proteins

| . | Latency, d . | WBC counts, 106/mL . | Blasts in PB, % . | Spleen weight, g . | Liver weight, g . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | N/A | 6.9 ± 1.2 | 0 ± 0 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.45 ± 0.12 |

| MLL-FKHRL1* | 157 ± 70 | 11.7 ± 8.3 | 2 ± 1 | 0.4 ± 0.11 | 0.94 ± 0.21 |

| MLL-AFX* | 185 ± 115 | 10.7 ± 7.3 | 5 ± 2 | 0.5 ± 0.13 | 1.13 ± 0.28 |

| MLL-AF10* | 52 ± 8 | 222 ± 94 | 54 ± 24 | 1.80 ± 0.24 | 2.25 ± 0.45 |

| . | Latency, d . | WBC counts, 106/mL . | Blasts in PB, % . | Spleen weight, g . | Liver weight, g . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | N/A | 6.9 ± 1.2 | 0 ± 0 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.45 ± 0.12 |

| MLL-FKHRL1* | 157 ± 70 | 11.7 ± 8.3 | 2 ± 1 | 0.4 ± 0.11 | 0.94 ± 0.21 |

| MLL-AFX* | 185 ± 115 | 10.7 ± 7.3 | 5 ± 2 | 0.5 ± 0.13 | 1.13 ± 0.28 |

| MLL-AF10* | 52 ± 8 | 222 ± 94 | 54 ± 24 | 1.80 ± 0.24 | 2.25 ± 0.45 |

WBC indicates white blood cell; PB, peripheral blood; and N/A, not applicable.

Values shown are the mean (± SEM) from MLL-FKHRL1 (n = 6), MLL-AFX (n = 10), and MLL-AF10 (n = 10) mice at the time mice were killed.

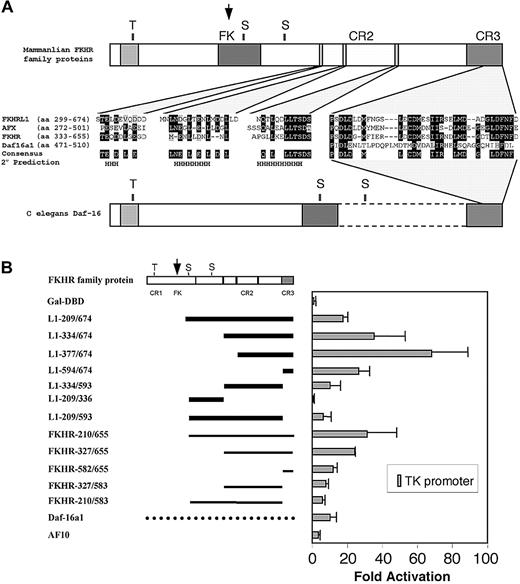

Two transcriptional effector domains of FKHRL1 are required for oncogenic activation of MLL

To establish the molecular contributions of FKHRL1 to MLL-mediated leukemogenesis, structure-function analyses were conducted. Forkhead subfamily proteins display a conserved domain structure consisting of the forkhead DBD and 3 additional regions of sequence similarity designated CR1, CR2, and CR3 (Figure 3). To assess transcriptional effector properties, transient transfection assays were performed in 293 and COS7 cells using various fragments of FKHRL1 fused to the Gal4-DBD. The 3′ portion of FKHRL1, which is consistently present in MLL fusion proteins, exhibited strong transactivation properties on all 3 promoters tested (HSV-TK, adenovirus E1b, and myelomonocytic growth factor; Figure 3B). Deletion mapping further revealed the presence of a potent transactivation domain in CR3 (amino acids 594-674) and a weaker transactivation region in CR2 (amino acids 334-593).

Structural and functional conservation of transcriptional domains in mammalian FKHR family proteins.

(A) Schematic diagram showing the conserved domains and sequence alignments of mammalian FKHR family proteins and their C elegans ortholog Daf-16. CR3 is highly acidic and conserved in all mammalian and nematode orthologs. CR2 consists of 3 conserved helical structures, which are absent in Daf-16. Dark and light shadings represent identical residues and conserved residues, respectively. S and T represent the conserved serine and threonine phosphorylation residues, respectively. H indicates the minimal predicted α helical secondary structures conserved in all mammalian homologs. (B) Transient transfection assays. Schematic diagram (left) illustrates the conserved general structure of mammalian FKHR family proteins. Arrow indicates the site of fusion with MLL. Solid horizontal black lines indicate portions of FKHR or FKHRL1 fused to the Gal4-DBD for transactivation assays. Broken horizontal line indicates the full-length Daf-16a1 fusion with Gal4-DBD. Gal4-AF10 encodes the AF10 sequence (amino acids 682-1085) present in MLL-AF10. Normalized luciferase values are shown (right) for the average of 3 experiments using a reporter gene under control of the HSV-TK promoter. Similar results were obtained on reporter constructs containing the adenoviral E1b or myelomonocytic growth factor receptor promoters (not shown). Comparable expression levels of the Gal4 constructs were confirmed by Western blot analysis (data not shown).

Structural and functional conservation of transcriptional domains in mammalian FKHR family proteins.

(A) Schematic diagram showing the conserved domains and sequence alignments of mammalian FKHR family proteins and their C elegans ortholog Daf-16. CR3 is highly acidic and conserved in all mammalian and nematode orthologs. CR2 consists of 3 conserved helical structures, which are absent in Daf-16. Dark and light shadings represent identical residues and conserved residues, respectively. S and T represent the conserved serine and threonine phosphorylation residues, respectively. H indicates the minimal predicted α helical secondary structures conserved in all mammalian homologs. (B) Transient transfection assays. Schematic diagram (left) illustrates the conserved general structure of mammalian FKHR family proteins. Arrow indicates the site of fusion with MLL. Solid horizontal black lines indicate portions of FKHR or FKHRL1 fused to the Gal4-DBD for transactivation assays. Broken horizontal line indicates the full-length Daf-16a1 fusion with Gal4-DBD. Gal4-AF10 encodes the AF10 sequence (amino acids 682-1085) present in MLL-AF10. Normalized luciferase values are shown (right) for the average of 3 experiments using a reporter gene under control of the HSV-TK promoter. Similar results were obtained on reporter constructs containing the adenoviral E1b or myelomonocytic growth factor receptor promoters (not shown). Comparable expression levels of the Gal4 constructs were confirmed by Western blot analysis (data not shown).

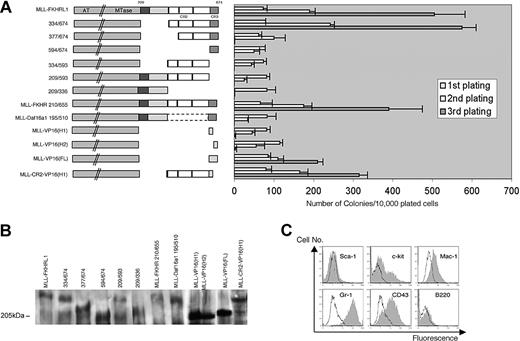

Various MLL-FKHRL1 constructs were tested for their ability to immortalize myeloid progenitors in vitro (Figure4A). Retroviral constructs used for these assays displayed similar transduction efficiencies as determined by enumeration of colony numbers in methylcellulose medium with or without G418 selection in the first round of plating. Expression of each construct was confirmed in COS7 cells and in primary transduced hematopoietic progenitors by Western blot and RT-PCR analyses, respectively (Figure 4B and data not shown). MLL-FKHRL1 209/336, containing the forkhead DBD and consensus PKB phosphorylation sites, failed to immortalize hematopoietic progenitors, and deletion of these domains in MLL-FKHRL1 334/674 did not impair transformation ability (Figure 4A). Conversely, constructs lacking either CR3 or CR2 (MLL-FKHRL1 334/593, MLL-FKHRL1 209/593, and MLL-FKHRL1 594/674) were unable to enhance the self-renewal of progenitors under these conditions. Although MLL-FKHRL1 377/674, which contained a complete CR3 but only part of CR2, yielded significant numbers of colonies in the second round of plating, the colony numbers dropped dramatically in the third plating, indicating an inability to immortalize hematopoietic progenitors (Figure 4A). These results demonstrate that oncogenic activity of MLL-FKHRL1 requires 2 transcriptional effector domains (CR2 and CR3) of FKHRL1.

CR2 and CR3 are consistently required for immortalization of myeloid progenitors by MLL-forkhead fusion proteins.

(A) Deletion mutants used for hematopoietic transformation assays are shown schematically on the left. Bar graph (right) indicates the number of colonies generated by the respective constructs in serial replating assays (means ± SDs, n = 3). (B) Western blot analysis demonstrating expression of MLL fusion constructs identified above the respective gel lanes. (C) Phenotypic analysis of cells transduced by MLL-FKHR. Gray histograms represent FACS staining obtained with antibodies specific for the indicated cell surface antigens. Black lines represent staining obtained with isotype control antibodies.

CR2 and CR3 are consistently required for immortalization of myeloid progenitors by MLL-forkhead fusion proteins.

(A) Deletion mutants used for hematopoietic transformation assays are shown schematically on the left. Bar graph (right) indicates the number of colonies generated by the respective constructs in serial replating assays (means ± SDs, n = 3). (B) Western blot analysis demonstrating expression of MLL fusion constructs identified above the respective gel lanes. (C) Phenotypic analysis of cells transduced by MLL-FKHR. Gray histograms represent FACS staining obtained with antibodies specific for the indicated cell surface antigens. Black lines represent staining obtained with isotype control antibodies.

A synthetic MLL-FKHR fusion protein transforms myeloid progenitors in vitro

FKHR is a mammalian FKHR subfamily protein that is involved in chromosomal translocation-mediated protein fusions in ARMs but not leukemias. However, its high-sequence conservation, particularly within the CR2 and CR3 domains, suggested that it may also oncogenically activate MLL. To investigate this possibility, the oncogenic potential of a synthetic MLL-FKHR fusion protein was tested in myeloid progenitors. MLL-FKHR–transduced cells displayed altered growth properties in vitro as evidenced by continued clonogenic potential on serial replating in methylcellulose (Figure 4A). MLL-FKHR–immortalized cells showed similar morphology and immunophenotype (c-kit+/Mac-1+/Gr-1+/Sca-1−/CD19−/CD3−) as progenitors immortalized by MLL-FKHRL1 and MLL-AFX,15representative of early myeloid progenitor derivation (Figure 4C). The 3′ portion of FKHR, which was synthetically fused with MLL and matches sequences fused to PAX3 or PAX7 in ARMs, displayed strong transactivation activity on all promoters tested (Figure 3B) consistent with previous findings using gene-specific promoter-driven reporters.19 20 Potent and weak transactivation domains were mapped in the CR3 and CR2 of FKHR, respectively. These data suggest that transcriptional effector domains found in all mammalian FHKR subfamily proteins are functionally conserved with respect to their abilities to oncogenically activate MLL.

MLL is not activated by fusion with the Caenorhabditis elegans ortholog of mammalian forkhead subfamily proteins

Daf-16 is the nematode ortholog of mammalian FKHR subfamily proteins (for a review, see Kops and Burgering21) and shares an overall conserved domain structure, but appears to lack CR2 and exhibits only restricted similarity to the acidic region of mammalian CR3 (Figure 3A). In transient transfection assays, Daf-16 displayed relatively weak transactivation properties on promoters that were potently activated by mammalian FKHR subfamily proteins (Figure3B). Nevertheless, its transactivation capacity was at least as potent as that of AF10 (Figure 3B), which results in aggressive acute leukemias as a MLL-AF10 fusion protein (Figure 2A and DiMartino et al18). The ability of Daf-16 to oncogenically activate MLL was evaluated as a synthetic MLL–Daf-16 fusion protein containing a 3′ portion of Daf-16 comparable to those of mammalian FKHR subfamily proteins fused with MLL in acute leukemias. In methylcellulose assays, MLL–Daf-16–transduced cells exhausted most of their proliferative capability in the first 2 rounds of plating (Figure 4A). Although a few colonies were seen in the second plating, analogous to transduction experiments with MLL-FKHRL1 594/674, no colonies were obtained in the third plating. Therefore, Daf-16 cannot activate MLL.

Oncogenic activation of MLL by VP16 also requires 2 transcriptional effector domains

We hypothesized that the inactivity of MLL–Daf-16 may be due to the lack of a CR2 motif. Consistent with this possibility, simple fusion of MLL with the potent minimal transactivation domain (MTD/H1) of VP16 was also incapable of transforming hematopoietic progenitors.15 Analogous to FKHRL1, the VP16 transactivation domain constitutes 2 distinct functional subdomains, known as the proximal (H1) and distal (H2) domains, which display strong and weak transactivation properties, respectively.22 23 Thus, it was of interest to determine if MLL-VP16, like MLL-forkhead fusion proteins, may require both of its transcriptional effector subdomains for transformation. Direct fusion of the H1 or H2 domains to MLL did not result in transformation (Figure 4A). However, a synthetic MLL fusion protein containing both H1 and H2 of VP16 (MLL-VP16(FL)) transformed myeloid progenitors, demonstrating a bifunctional contribution of VP16 to MLL-mediated transformation.

To further investigate the functional significance of CR2 for MLL-mediated transformation, we tested the transformation abilities of a synthetic MLL construct containing the CR2 from FKHRL1 fused with the H1 domain of VP16 (MLL-CR2-VP16(H1)). This construct, in contrast to MLL-VP16(H1), enhanced the replating potential of myeloid progenitors and resulted in their immortalization. FACS analysis confirmed the early myeloid immunophenotype of cells transformed by MLL-VP16(FL) or MLL-CR2-VP16(H1) (c-kit+/Mac-1+/Gr-1+/Sca-1−/CD19−/CD3−; data not shown) similar to that displayed by MLL-FKHRL1 immortalized cells (Figure 1C). Thus, addition of CR2 conferred oncogenic potential on the otherwise oncogenically inactive MLL-VP16(H1). These studies suggest that CR2 is a critical component in cooperating with acidic transactivation domains in MLL-mediated transformation.

Discussion

Our studies demonstrate that MLL-FKHRL1 enhances the self-renewal of myeloid progenitors and induces acute myeloid leukemia in mice with a phenotype comparable to human disease bearing this genetic aberration. We also demonstrate that the leukemogenic potential of MLL-FKHRL1 is remarkably similar to that of MLL-AFX, another MLL-forkhead fusion protein associated with human leukemias. In mice, MLL-FKHRL1 and MLL-AFX induced leukemias with similar latencies and pathologic presentations, which are notably different from the more aggressive disease induced by other MLL fusion proteins such as MLL-AF10 or MLL-ENL.2,18 The contrasting disease potentials of MLL fusion proteins in our murine myeloid transformation assay are consistent with different clinical behaviors of human leukemias bearing MLL fusion genes, some displaying aggressive courses (eg, MLL-AF10, MLL-AF4), whereas others have better outcomes (eg, MLL-AF9).24-26 Our findings provide experimental support that MLL fusion partners play a role in determining some of the biologic characteristics of MLL-associated leukemias.

All 3 mammalian forkhead subfamily proteins (FKHR, FKHRL1, and AFX) activate the oncogenic potential of MLL in myeloid progenitors, whereas Daf-16 lacks this ability. This is consistent with recent studies showing that FKHRL1 and Daf-16 are not functionally identical, although they are regulated by similar mechanisms.27 Forced expression of FKHRL1 in Daf-16 mutants only partially rescued dauer formation phenotypes under restrictive conditions, suggesting intrinsic functional differences between these orthologous proteins. Differences in transcriptional properties have also been observed for the various forkhead proteins.16 FKHR (and Daf-16) but not AFX function as accessory factors for the glucocorticoid response by recruiting the p300/CREB-binding protein (CBP)/steroid receptor coactivator–1 (SRC-1) coactivator complex to a forkhead factor site in the insulinlike growth factor–binding protein 1 promoter. AFX does not interact with SRC-1 or respond to glucocorticoid or insulin, although it is capable of interacting with the KIX domain of CBP and supporting basal transcription, as is the case for Daf-16 and FKHR. Thus, the mammalian forkhead subfamily proteins may not be functionally equivalent, yet they all share the potential for activation of MLL.

Our structure/function studies of MLL-FKHRL1 implicate 2 conserved transcriptional effector domains as critically important for MLL-mediated oncogenesis. An absolute requirement for both CR2 and CR3 in MLL-mediated cellular transformation was also observed for MLL-AFX,15 further demonstrating that specific contributions from each of these domains are critical for transformation. The pathogenic importance of these domains has also been suggested by studies of PAX-FKHR, which is associated with ARMs, where both CR2 and CR3 of FKHR are necessary for full oncogenicity in NIH-3T3 soft agar transformation assays28 29 (C.W.S. and M.L.C., unpublished observation, March 2002). Further evidence that CR2 and CR3 are functionally conserved domains required for oncogenesis derives from comparisons of synthetic MLL-FKHR and MLL–Daf-16 fusion proteins. The former was capable of enhancing the self-renewal of hematopoietic progenitors, whereas MLL-Daf-16, which lacks CR2, was not.

CR3 has features of an acidic activation domain comparable in potency to the minimal transactivation domain (H1) of VP16 in transient transcriptional assays using a variety of promoters and cell types15 (and data not shown). Furthermore, the CR3 domains of 3 forkhead proteins (FKHR, AFX, and Daf-16) have been shown to bind the KIX domain of CBP in vitro,15 16 and FKHRL1 is also likely to bind CBP given its sequence conservation. Nevertheless, as direct fusions with MLL, the CR3 and H1 domains are not sufficient for oncogenic activation of MLL, despite their clear requirements in this process. Although the molecular functions of CR2 are not known, further insights gained by studying the synthetic MLL-VP16 fusion constructs suggest that CR2 can cooperate with other transactivation domains in promoting MLL-mediated leukemogenesis.

Previous studies on VP16 have shown that the proximal H1 and distal H2 domains function via 2 distinct pathways.22,23,30 H1 may recruit general transcription factors (eg, TFIID and TFIIB) and mediators (TRAP/SMCC/ARC), whereas H2 recruits histone acetyltransferase (eg, CBP) for chromatin remodeling. This is supported by the recent findings that VP16-mediated transcriptional activation from chromatin templates requires both H1 and H2, whereas H1 is necessary and sufficient for transcription from naked DNA templates.30 The requirement of both H1 and H2 for oncogenic activation of MLL suggests that deregulation of transcriptional control by MLL fusion proteins involves both chromatin remodeling and recruitment of general transcriptional machinery for assembly of the preinitiation complex. The functional importance of CR2 in MLL-mediated transformation was further demonstrated by its ability to confer oncogenic activity on the otherwise nontransforming MLL-VP16(H1) in domain-swapping experiments. This result suggests that CR2 may mimic H2 function in promoting chromatin remodeling for transcriptional activation, although the actual function of CR2 remains to be determined. Nevertheless, the dual requirement for CR2/CR3 of forkhead proteins or H1/H2 of VP16 suggests that oncogenic conversion of MLL may depend on recruitment of multiple coactivators or basal components to deregulate the expression of critical target genes involved in cellular transformation.

In summary, we demonstrate that oncogenic activation of MLL is conserved among the mammalian forkhead subfamily proteins and requires 2 transcriptional effector domains, CR2 and CR3. The requirement for CR2/H2 in addition to a strong transactivation domain (CR3, H1) in cellular transformation suggests a bifunctional contribution for oncogenic activation of MLL by direct fusion with transactivator proteins. Future studies delineating the molecular functions of these domains will provide important insights in understanding the mechanisms of MLL-mediated transformation.

We thank M. C. Alexander-Bridges, K. C. Arden, J. Lipsick, and M. F. Roussel for providing essential reagents to conduct these studies and members of the Cleary laboratory for helpful discussions and advice. We also thank A. R. Kola for technical assistance and Caroline Tudor and Erica So for assistance with artwork.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, August 22, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1785.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (CA55209), the Children's Health Initiative, and in part by a Croucher Foundation research grant (C.W.S.). C.W.S. is a Special Fellow of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Michael L. Cleary, Department of Pathology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA 94305; e-mail:mcleary@stanford.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal