Abstract

Recent data have implicated macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α) in multiple myeloma (MM)-associated osteolysis. However, it is unclear whether the chemokine's effects are direct, to enhance osteolysis, or indirect and mediated through a reduction in tumor burden, or both. It is also unclear whether MIP-1α requires other factors such as receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) for its effects on bone. In murine 5TGM1 (Radl) myeloma-bearing mice, administration of neutralizing anti-MIP-1α antibodies reduced tumor load assessed by monoclonal paraprotein titers, prevented splenomegaly, limited development of osteolytic lesions, and concomitantly reduced tumor growth in bone. To determine the effects of MIP-1α on bone in vivo, Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells secreting human MIP-1α (CHO/MIP-1α) were inoculated into athymic mice. Mice bearing intramuscular CHO/MIP-1α tumors developed lytic lesions at distant skeletal sites, which occurred earlier and were larger than those in mice with CHO/empty vector (EV) tumors. When experimental metastases were induced via intracardiac inoculation, mice bearing CHO/MIP-1α tumors developed hypercalcemia and significantly more osteolytic lesions than mice bearing CHO/EV tumors, with intramedullary CHO/MIP-1α tumors associated with significantly more tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase-positive (TRAP+) osteoclasts. Injection of recombinant MIP-1α over calvariae of normal mice evoked a striking increase in osteoclast formation, an effect dependent on RANK/RANKL signaling because MIP-1α had no effect in RANK-/- mice. Together, these results establish that MIP-1α is sufficient to induce MM-like destructive lesions in bone in vivo. Because, in the 5TGM1 model, blockade of osteoclastic resorption in other situations does not decrease tumor burden, we conclude that MIP-1α exerts a dual effect in myeloma, on osteoclasts, and tumor cells. (Blood. 2003;102:311-319)

Introduction

Murine macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α)/CCL3 is a member of a superfamily of structurally related and secreted low molecular weight cytokines involved in the directed migration(chemotaxis) and activation of cells that have been implicated in inflammation, wound healing, hematopoiesis, and tumorigenesis.1-4 MIP-1α was originally isolated as a macrophage product with inflammatory and chemotactic properties.5,6 To date, 4 chemokine subfamilies (CXC [α], CC [β], C [γ], and CX3C) have been described based on the position of conserved cysteine residues, andMIP-1α belongs to the CC subfamily. The 4 classes of chemokines act on different cell types, and members of the CC subfamily including MIP-1α promote migration of monocytes/macrophages and T lymphocytes.1,3,7,8

Multiple myeloma (MM), the second most common adult hematologic malignancy—affecting 14 000 patients in the United States and accounting for 1% to 2% of cancer-related deaths9 —is associated with severe and progressive bone destruction. The high morbidity and mortality rates associated with this plasma cell malignancy are primarily due to the effects of the unremitting osteolysis and occasional hypercalcemia.10 There is unequivocal evidence that myeloma-induced bone loss is due to increased osteoclast activity induced by an as yet unidentified locally acting factor(s).10 MIP-1α is expressed and secreted by myeloma cells freshly isolated from patients as well as human myeloma cell lines.11-14 Levels of MIP-1α are elevated in bone marrow plasma of myeloma patients compared with other lymphoid hematologic malignancies and normal controls.11,12 Gene expression profiling studies also show that MIP-1α expression in mononuclear cells isolated from the bone marrow of myeloma patients is several-fold higher than in those from healthy subjects.14 MIP-1α stimulates chemotaxis of human osteoclast precursors15 and formation of human osteoclast-like cells in vitro.12,15,16 In nonhuman systems, MIP-1α has also been shown to be chemotactic for cells at various stages in osteoclast ontogeny including murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-forming units (CFU-GMs)17 as well as isolated rat osteoclasts.18 MIP-1α also stimulates the formation of osteoclast-like cells in rat, rabbit, and porcine bone cell cultures.12,19-21

Importantly, recent reports have implicated MIP-1α in the osteolysis associated with MM. Tumor cells isolated from myeloma patients with active disease or with multiple bone lesions secreted significantly higher amounts of MIP-1α than tumor cells from patients with stable disease or patients who have none or only one radiologically evident bone lesion.11-13 Furthermore, neutralizing antibodies to MIP-1α partially blocked formation of osteoclast-like cells in vitro induced by freshly isolated marrow plasma from patients with myeloma or by conditioned media from human myeloma cell lines.11,12 However, it is still unclear how MIP-1α exerts its effects in vivo in myeloma, whether it affects osteoclast formation and activation directly or indirectly through a reduction in the tumor itself, or both. Moreover, there is no direct evidence that MIP-1α can induce osteoclastic bone resorption in vivo. It was reported recently that antisense inhibition of MIP-1α production blocked bone destruction in a model in which Epstein Barr virus-positive human B-lymphoblastoid ARH-77 cells induce osteolysis in irradiated severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice.22 Although data from this study indicate that MIP-1α is necessary for osteolysis in vivo, the question of whether MIP-1α is sufficient for tumor to form and grow in bone was not addressed.

In this paper, we show that MIP-1α has a dual antitumor and antiosteolytic effect in myeloma in vivo in the murine 5TGM1 model of human myeloma bone disease. The 5T (Radl) series of myelomas originated spontaneously in aging inbred C57BL mice of the KaLwRij substrain.23,24 Cytogenetic and molecular genetic analyses of these murine myelomas have shown that they closely resemble human myelomas.25-27 We reported previously that when 5T33 myeloma-derived 5TGM1 cells are inoculated intravenously in syngeneic or bg-nu-xid mice, they home almost exclusively to the skeleton and infrequently to the spleen.28 Expansion within these sites results in radiographically detectable lytic bone lesions, markedly elevated serum titers of the monoclonal paraprotein, and splenomegaly.29,30 We found that in this myeloma model, functional blockade of MIP-1α bioactivity by systemically administered neutralizing anti-MIP-1α antibodies not only blocked osteoclastic bone destruction but also reduced overall tumor burden and prevented splenomegaly. In addition, intramuscular or intracardiac inoculation of Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells engineered to constitutively secrete human MIP-1α in mice resulted in radiographically detectable bone lesions, osteolysis, and hypercalcemia, features characteristic of MM. We also show that direct injection of recombinant MIP-1α over the calvariae of mice induced a robust increase in the number of osteoclasts. Together, these results strongly suggest that MIP-1α production by myeloma cells in the bone marrow microenvironment is necessary to induce skeletal pathology typical of myeloma. These data have important therapeutic implications because they strongly indicate that strategies based on functional blockade of MIP-1α bioactivity (eg, using small molecule, synthetic antagonists of MIP-1α receptor signaling) may be efficacious in myeloma.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Recombinant murine and human MIP-1α, human and mouse MIP-1α enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits, antimouse MIPα (purified monoclonal rat IgG2a; clone no. 39624.11), and isotype control (purified rat monoclonal IgG2a; clone no. 54447.11) were from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). The antimouse MIP-1α antibodies do not cross-react with mouse MIP-1β. Unless otherwise specified, all other chemical and tissue culture reagents were from Sigma Chemicals (St Louis, MO) and Life Technologies (Gaithersburg, MD), respectively.

Construction of CHO cells expressing MIP-1α

The complete sequence for human MIP-1α cDNA was amplified by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from a pool of RNA isolated from peripheral blood lymphocytes obtained from 3 healthy individuals. The primers used for amplification were as follows: MIP-1α sense primer 5′-GGCAGCAGACAGTGGTCAGT-3′, and MIP-1α antisense primer 5′-TTGGTGCCATGACTGCCTAC-3′.

A high-fidelity DNA polymerase enzyme (Thermostable Taq-polymerase; Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) was used to decrease the chance of mutations in the end product. The PCR reaction was heated to 94°C for 4 minutes before being submitted to 35 cycles of 1 minute at 94°C, 1 minute at 55°C, and 1 minute at 72°C and then kept for 8 minutes at 72°C. The PCR product was cloned into a pcDNA3.1 plasmid following instructions provided by the supplier (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and selected clones were then submitted to automated sequencing (ABI-prism; Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA). To generate stable CHO cell transfectants expressing MIP-1α, CHO cells (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) were plated in 6-well plates at 4 × 105 cells per well in 5 mL HAM-F12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (10% FBS HAMF12) and grown overnight in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. The following day the media were replaced by serum-free OPTIMEM media, and a mixture of MIP-1α/pcDNA3.1 plasmid and geneticin (1 μg to 5 μL, respectively) was added to each well for 6 hours. At the end of the 6-hour incubation period, the cells were washed and grown in 10% FBS HAM-F12 media for 36 hours before adding geneticin (500 μg/mL) to select for positive clones. The cells surviving the selective media were submitted to a limiting dilution process to isolate clones of cells expressing higher amounts of MIP-1α. Several clones were obtained and screened by ELISA.31 A clone expressing 50 ng/mL MIP-1α (referred to hereafter as CHO/MIP-1α) was selected for use in in vivo experiments.

Cells

The 5TGM1 myeloma cell line was subcloned from a stroma-independent cell line originally established from the parent murine 5T33 (IgG2bκ) myeloma23 and grown in long-term suspension culture.28-30 CHO cell clones were maintained as adherent cultures in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) or HAM-F12 supplemented with 10% FBS (Summit Biotechnology, Fort Collins, CO), 1% glutamine, and antibiotics. Cultured cells were harvested and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a concentration of 106/100 μL for inoculation into nude mice.

Animals

Animal studies were conducted using weight-matched, 4- to 6-week-old (18 to 25 g) female BALB/c athymic nude mice (homozygous, nu/nu) (National Cancer Institute [NCI], Frederick, MD) or female ICR Swiss mice (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) except as otherwise stated. Receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB (RANK) null mutant mice (C57BL/6 × 129 hybrids)32 and age-matched, wild-type littermates were kindly provided by Immunex (Seattle, WA). Studies were approved by the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (UTHSCSA) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health's (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Mice were housed in isolator cages in an American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited animal facility. Autoclaved chow (Sprague-Dawley, San Diego, CA) and acidified water were provided ad libitum.

5TGM1 myeloma model

Myeloma lesions were induced in bg-nu-xid mice (BALB/c; NCI) by inoculation of 106 5TGM1 myeloma cells through tail veins. Thereafter, the mice were randomized into groups to receive either monoclonal rat antimouse MIPα antibody, isotype rat IgG2a, or PBS by intraperitoneal injections according to dosing schedule illustrated in Figure 1A. Sera were prepared from whole blood obtained by retro-orbital sinus bleed under light methoxyflurane-induced anesthesia and stored frozen until mouse IgG2bκ was assayed using a specific ELISA (with no species cross-reactivity or cross-reactivity to other mouse immunoglobulins).29

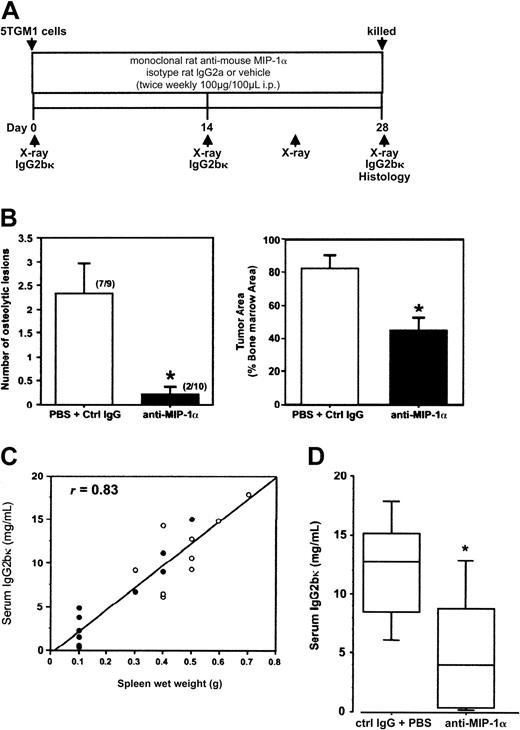

Marked reduction in myeloma bone disease and tumor burden in vivo as a result of functional blockade of MIP-1α bioactivity with neutralizing antibodies to MIP-1α (A) Treatment schedule. (B) Neutralization of MIP-1α bioactivity significantly inhibited the development of osteolytic lesions and reduced skeletal tumor volume in myeloma-bearing mice. Left panel: anti-MIP-1α antibodies significantly reduced the number of osteolytic lesions compared with treatment with isotype IgG2a and PBS (number in parentheses represents mice with at least one lesion per mouse in group). Right panel: the anti-MIP-1α antibodies also significantly reduced the proportion of the marrow cavity occupied by tumor in bones of the hind limbs compared with treatment with isotype IgG2a or PBS (P = .0011). (C) Treatment with anti-MIP-1α antibodies resulted in a significant reduction in incidence of splenomegaly in myeloma-bearing mice (• indicates values for individual mice treated with anti-MIP-1α antibodies; ○, values for control mice that received isotype IgG or vehicle). All control mice had significantly enlarged spleens (at least 0.3 g), whereas only 4 of 10 mice that received anti-MIP-1α antibody had splenomegaly (normal non-tumor-bearing mouse spleen, 0.1 g or less). There was a positive correlation between splenic wet weights and serum IgG2bκ levels (r = 0.83). (D) Treatment with anti-MIP-1α antibodies significantly reduced serum IgG2bκ titers in 7 of 10 tumor-bearing mice (5.45 ± 1.56 mg/mL), below the median for the pooled controls (9.26 mg/mL); line, median; box, 25% to 75%; bar, 95% confidence interval (“Statistical Analysis”).

Marked reduction in myeloma bone disease and tumor burden in vivo as a result of functional blockade of MIP-1α bioactivity with neutralizing antibodies to MIP-1α (A) Treatment schedule. (B) Neutralization of MIP-1α bioactivity significantly inhibited the development of osteolytic lesions and reduced skeletal tumor volume in myeloma-bearing mice. Left panel: anti-MIP-1α antibodies significantly reduced the number of osteolytic lesions compared with treatment with isotype IgG2a and PBS (number in parentheses represents mice with at least one lesion per mouse in group). Right panel: the anti-MIP-1α antibodies also significantly reduced the proportion of the marrow cavity occupied by tumor in bones of the hind limbs compared with treatment with isotype IgG2a or PBS (P = .0011). (C) Treatment with anti-MIP-1α antibodies resulted in a significant reduction in incidence of splenomegaly in myeloma-bearing mice (• indicates values for individual mice treated with anti-MIP-1α antibodies; ○, values for control mice that received isotype IgG or vehicle). All control mice had significantly enlarged spleens (at least 0.3 g), whereas only 4 of 10 mice that received anti-MIP-1α antibody had splenomegaly (normal non-tumor-bearing mouse spleen, 0.1 g or less). There was a positive correlation between splenic wet weights and serum IgG2bκ levels (r = 0.83). (D) Treatment with anti-MIP-1α antibodies significantly reduced serum IgG2bκ titers in 7 of 10 tumor-bearing mice (5.45 ± 1.56 mg/mL), below the median for the pooled controls (9.26 mg/mL); line, median; box, 25% to 75%; bar, 95% confidence interval (“Statistical Analysis”).

Mouse calvarial resorption model

The effect of recombinant human MIP-1α or murine MIP-1α on bone resorption was assessed by twice daily injections for 5 days into the subcutaneous tissue overlying parietal bones on the right side of the calvariae of normal Swiss ICR mice by use of a Hamilton syringe,33 with a control group of mice receiving vehicle (same volume). Mice were humanely killed 4 days after the last injection and calvariae removed and processed for histology and cytochemistry.

Experimental metastasis model

To investigate the effect of circulating MIP-1α, 105 CHO/MIP-1α or empty vector-transfected (CHO/EV) cells were injected directly into left thigh muscles of nude mice. To examine the local effect of MIP-1α within the marrow microenvironment, tumors were induced in medullary cavities of long bones of the limbs by inoculation of 106 CHO/MIP-1α or CHO/EV cells into left ventricles of nude mice.

Fetal rat long bone assay

To assess bone resorption, the 45 Ca release assay was performed using fetuses from timed pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats (day 18 gestation) injected subcutaneously with 250 μCi (9.25 MBq) [45Ca]calcium chloride (ICN Biomedicals, Irvine, CA) 24 hours prior to assay as previously described.34 Briefly, explanted radiolabeled long bone rudiments were incubated in the presence or absence of conditioned media harvested from cultured CHO cell clones. Culture media were replenished every 48 hours and expended media saved. At the end of the culture period, radioactivity in both media and trichloroacetic acid extracts of the bones was determined separately by liquid scintillation counting. Radioactivity in the media harvested at earlier time points was combined with that of the final conditioned media and represents total medium count. The amount of 45Ca released (counts per minute [cpm]) from individual bones over the total 5-day culture period (total medium cpm) was calculated as a percentage of total radioactivity (total medium cpm + residual bone cpm).

Radiographic analysis

High-resolution whole body radiographs of ketamine-anesthesized mice were obtained with the animals immobilized in a prone position on Kodak X-Omat AR radiographic film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) using a Faxitron Cabinet X-ray unit at 35 kilovolt (peak) for 6 seconds (Faxitron X-ray, Buffalo Grove, IL).29,34 Radiographs were taken just before tumor inoculation and weekly thereafter. Analysis of number and surface area of radiolucent lesions was performed by a trained observer blinded to the composition of the different groups and treatments received.

Whole blood ionized calcium measurements

Whole blood samples were collected by retro-orbital sinus puncture into disposable heparinized capillary tubes under light methoxyflurane-induced anesthesia for immediate calcium measurements using a Ciba Corning 634 ISE Ca2+/pH analyzer.

Bone histologic and cytochemical analyses

Animals were killed by cervical dislocation under ketamine-induced anesthesia and skeletons removed, fixed in 10% formalin for 48 hours, and decalcified in 14% EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid). For experiments in which MIP-1α had been injected into overlying subcutaneous tissues over the calvariae, the anterior half of the frontal bones and most of the occipital bones were trimmed before embedding in paraffin with the cut edges adjacent to the lambdoid sutures at the bottom of the cassettes. With the anterior tip of the foramen magnum as a fixed starting point in each case, multiple sections (5 μm thick) of the parietal bones in a posteroanterior direction were cut. Three sections at nonconsecutive levels for all calvariae were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). For each level chosen, a consecutive section was stained cytochemically for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) activity, a well-recognized marker of osteoclasts in vivo.34 Images of the sagittal suture area between the parietal bones on the 3 nonconsecutive H&E-stained sections and corresponding TRAP sections were digitally captured with a CoolSNAP color camera (Imaging Research St Catharines, ON, Canada) linked to an Olympus BH-2 microscope attached to a computer and a frame-grabber board. To determine mean sagittal suture area, soft tissues in the suture area on the 3 H&E sections for each mouse were traced manually and quantified with the OsteoMeasure software (Osteometrics, Atlanta, GA).35 The bone surface in each suture area was similarly traced and the suture perimeter averaged. The number of TRAP+ multinucleated cells apposed to bone surfaces in each suture area was then enumerated and expressed either as osteoclasts per millimeter of sutural bone perimeter or per square millimeter of suture area.

Fixed and decalcified long bones of tumor-bearing animals, embedded in paraffin, were sectioned along the midsagittal plane at 7 μm. Serial bone sections were stained with H&E and for TRAP activity, images of longitudinal sections of the tibiae and femorae were digitally captured as described above, and histomorphometric analyses performed at the proximal and distal metaphyses, respectively, using OsteoMeasure.29 The total number of TRAP+ cells aligned between tumor and bone was enumerated and expressed per millimeter of this interface.

Statistical analysis

Data from the bone resorption assay were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc testing using the Fisher PLSD (protected least significant difference) test (StatView 5.0.1; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The significance of difference in parameters measured in all other in vivo experiments was assessed using the Mann-Whitney U test for nonparametric data (StatView). Data presented (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4) represent means ± SEM. (* denotes P < .05 except otherwise stated.)

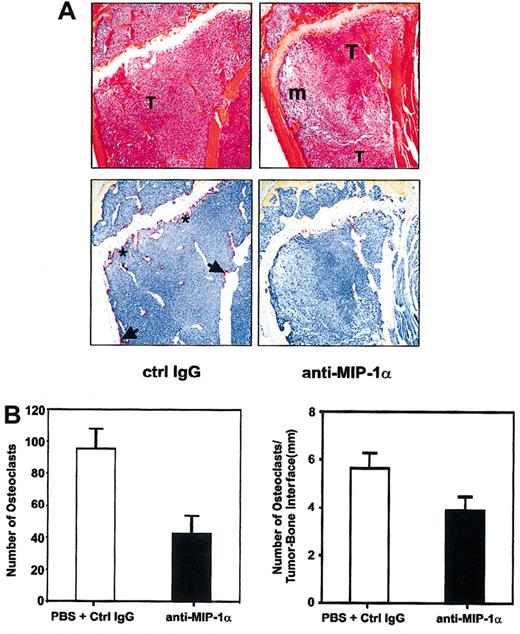

Inhibition of osteoclastic activity by anti-MIP-1α antibodies in myeloma-bearing mice. (A) Functional blockade of MIP-1α activity inhibited osteoclast formation and activity in tumor-bearing mice. Representative serial sections of tibiae of anti-MIP-1α antibody- and isotype IgG-treated mice stained with H&E (top row) or for TRAP activity (bottom row) were chosen to illustrate clear differences in osteoclast number and activity even when extent of tumor infiltration of marrow cavities was comparable. Note overall reduction in the number of osteoclasts and intensity of TRAP staining in the anti-MIP-1α section (right column), compared with the isotype IgG-treated section (left column). In the latter, osteoclasts are present not only on the primary spongiosum aspect of the growth plate (asterisks) but also along the endocortical surface (arrows). In contrast, in the anti-MIP-1α section, no osteoclasts are present on the endocortical surface and very few can be seen even where the tumor is apposed to the growth plate. Original magnification, × 10. T indicates tumor; m, marrow. (B) Histomorphometric analysis of osteoclast activity in bones of mice treated with anti-MIP antibodies or isotype-matched antibodies/PBS. Neutralization of MIP-1α bioactivity reduced osteoclast activity expressed either as total number of TRAP+ multinucleated osteoclasts aligned along the tumor-bone interface (left panel) or as number of osteoclasts per millimeter of tumor-bone interface (right panel).

Inhibition of osteoclastic activity by anti-MIP-1α antibodies in myeloma-bearing mice. (A) Functional blockade of MIP-1α activity inhibited osteoclast formation and activity in tumor-bearing mice. Representative serial sections of tibiae of anti-MIP-1α antibody- and isotype IgG-treated mice stained with H&E (top row) or for TRAP activity (bottom row) were chosen to illustrate clear differences in osteoclast number and activity even when extent of tumor infiltration of marrow cavities was comparable. Note overall reduction in the number of osteoclasts and intensity of TRAP staining in the anti-MIP-1α section (right column), compared with the isotype IgG-treated section (left column). In the latter, osteoclasts are present not only on the primary spongiosum aspect of the growth plate (asterisks) but also along the endocortical surface (arrows). In contrast, in the anti-MIP-1α section, no osteoclasts are present on the endocortical surface and very few can be seen even where the tumor is apposed to the growth plate. Original magnification, × 10. T indicates tumor; m, marrow. (B) Histomorphometric analysis of osteoclast activity in bones of mice treated with anti-MIP antibodies or isotype-matched antibodies/PBS. Neutralization of MIP-1α bioactivity reduced osteoclast activity expressed either as total number of TRAP+ multinucleated osteoclasts aligned along the tumor-bone interface (left panel) or as number of osteoclasts per millimeter of tumor-bone interface (right panel).

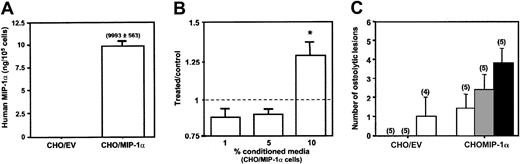

Osteolysis at distant skeletal sites in mice bearing intramuscular CHO/MIP-1α-secreting tumors. (A) Human MIP-1α was determined in media harvested from exponentially growing empty vector- and MIP-1α-expressing CHO cells (CHO/MIP-1α) by a specific ELISA. (B) Stimulation of osteoclastic bone resorption in 45Ca-labeled fetal rat long bone organ cultures by media conditioned by CHO/MIP-1α cells after 5 days. Data are expressed as a ratio of the basal level of stimulation induced by an equivalent concentration of empty vector-transfected (CHO/EV) cells. (C) Tumors were induced by inoculating tumor cells into left thigh muscles of BALB/c nu/nu mice (n = 5 per group), and radiographs were obtained at baseline and thereafter weekly for 5 weeks. Osteolytic lesions were evident in the contralateral hind limbs of CHO/MIP-1α tumor-bearing mice from week 3 and increased progressively thereafter. Lesions were discernable in the contralateral hind limb of only one CHO/EV tumor-bearing mouse, and this was after 5 weeks. □ indicates week 3; ▦, week 4; and ▪, week 5. See “Statistical analysis.”

Osteolysis at distant skeletal sites in mice bearing intramuscular CHO/MIP-1α-secreting tumors. (A) Human MIP-1α was determined in media harvested from exponentially growing empty vector- and MIP-1α-expressing CHO cells (CHO/MIP-1α) by a specific ELISA. (B) Stimulation of osteoclastic bone resorption in 45Ca-labeled fetal rat long bone organ cultures by media conditioned by CHO/MIP-1α cells after 5 days. Data are expressed as a ratio of the basal level of stimulation induced by an equivalent concentration of empty vector-transfected (CHO/EV) cells. (C) Tumors were induced by inoculating tumor cells into left thigh muscles of BALB/c nu/nu mice (n = 5 per group), and radiographs were obtained at baseline and thereafter weekly for 5 weeks. Osteolytic lesions were evident in the contralateral hind limbs of CHO/MIP-1α tumor-bearing mice from week 3 and increased progressively thereafter. Lesions were discernable in the contralateral hind limb of only one CHO/EV tumor-bearing mouse, and this was after 5 weeks. □ indicates week 3; ▦, week 4; and ▪, week 5. See “Statistical analysis.”

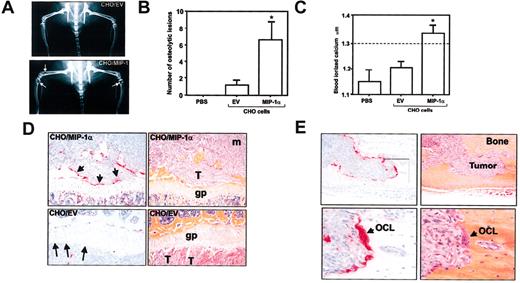

Osteolytic effects of MIP-1α in mice bearing intramedullary CHO/MIP-1α-secreting tumors induced by direct intracardiac inoculation of tumor cells. (A) Radiographs of lower limbs of nude mice 3 weeks after intracardiac inoculation of either CHO cell clones showing radiolucent lytic lesions (arrows) in a CHO/MIP-1α-bearing mouse but not CHO/EV mouse. (B) The number of lytic lesions in hind limbs of CHO/MIP-1α tumor-bearing mice was significantly greater than in control CHO/EV tumor-bearing mice. There were no lesions visible in mice injected with PBS. (C) Development of osteolytic lesions in CHO/MIP-1α tumor-bearing mice was associated with hypercalcemia. Whole blood ionized calcium levels in CHO/EV cells were not significantly different from those in mice injected with PBS. Upper limit of reference range for ionized calcium in nude mice: 1.3 mM (dashed line). See “Statistical analysis.” (D) Representative photomicrographs of tibiae of mice with intramedullary tumors induced by intracardiac inoculation of CHO/MIP-1α cells (top panels) and CHO/EV cells (bottom panels). Serial sections were stained with H&E (right panels) or stained for TRAP activity (left panels). A global increase in the number of TRAP+ osteoclasts is evident in the section of CHO/MIP-1α tumor-bearing mouse tibia, compared with that of tibia from mouse bearing CHO/EV tumor. An increased number of osteoclasts staining intensely positive for TRAP can be seen not only at CHO/MIP-1α tumor-bone interface but also along CHO/MIP-1α tumor-growth plate interface (short arrows). In the CHO/MIP-1α section, the marked increase in osteoclast activity is evident even on the primary spongiosum side of the growth plate where no tumor is present. In contrast, in the CHO/EV tumor, no osteoclasts are present even where the tumor is closely apposed to the growth plate (long arrows). T indicates tumor; gp, growth plate; m, normal marrow. Original magnification, × 20. (E) Representative photomicrograph of CHO/MIP-1α tumor in mouse tibia following induction of intramedullary metastases via intracardiac inoculation of CHO/MIP-1α cells, stained with H&E (right panels) or for TRAP activity (left panels). Top panels (at low original magnification, × 20) show a marked increase in number of TRAP+ osteoclasts evident all along the tumor-bone interface. In the bottom panels (depicting the inset) (at high original magnification, × 40), an intensely stained multinucleated osteoclast (OCL) is evident at the leading edge of the CHO/MIP-1α tumor.

Osteolytic effects of MIP-1α in mice bearing intramedullary CHO/MIP-1α-secreting tumors induced by direct intracardiac inoculation of tumor cells. (A) Radiographs of lower limbs of nude mice 3 weeks after intracardiac inoculation of either CHO cell clones showing radiolucent lytic lesions (arrows) in a CHO/MIP-1α-bearing mouse but not CHO/EV mouse. (B) The number of lytic lesions in hind limbs of CHO/MIP-1α tumor-bearing mice was significantly greater than in control CHO/EV tumor-bearing mice. There were no lesions visible in mice injected with PBS. (C) Development of osteolytic lesions in CHO/MIP-1α tumor-bearing mice was associated with hypercalcemia. Whole blood ionized calcium levels in CHO/EV cells were not significantly different from those in mice injected with PBS. Upper limit of reference range for ionized calcium in nude mice: 1.3 mM (dashed line). See “Statistical analysis.” (D) Representative photomicrographs of tibiae of mice with intramedullary tumors induced by intracardiac inoculation of CHO/MIP-1α cells (top panels) and CHO/EV cells (bottom panels). Serial sections were stained with H&E (right panels) or stained for TRAP activity (left panels). A global increase in the number of TRAP+ osteoclasts is evident in the section of CHO/MIP-1α tumor-bearing mouse tibia, compared with that of tibia from mouse bearing CHO/EV tumor. An increased number of osteoclasts staining intensely positive for TRAP can be seen not only at CHO/MIP-1α tumor-bone interface but also along CHO/MIP-1α tumor-growth plate interface (short arrows). In the CHO/MIP-1α section, the marked increase in osteoclast activity is evident even on the primary spongiosum side of the growth plate where no tumor is present. In contrast, in the CHO/EV tumor, no osteoclasts are present even where the tumor is closely apposed to the growth plate (long arrows). T indicates tumor; gp, growth plate; m, normal marrow. Original magnification, × 20. (E) Representative photomicrograph of CHO/MIP-1α tumor in mouse tibia following induction of intramedullary metastases via intracardiac inoculation of CHO/MIP-1α cells, stained with H&E (right panels) or for TRAP activity (left panels). Top panels (at low original magnification, × 20) show a marked increase in number of TRAP+ osteoclasts evident all along the tumor-bone interface. In the bottom panels (depicting the inset) (at high original magnification, × 40), an intensely stained multinucleated osteoclast (OCL) is evident at the leading edge of the CHO/MIP-1α tumor.

Results

Neutralization of MIP-1α bioactivity inhibits development of osteolytic lesions and slows tumor progression in myeloma-bearing mice

To test the hypothesis that MIP-1α is involved in the pathogenesis of myeloma-induced osteolysis, we investigated the effect of disrupting MIP-1α activity in vivo in the 5TGM1 myeloma model.28-30 Murine MIP-1α mRNA was detected in 5TGM1 cells by RT-PCR, and MIP-1α protein was measurable in 5TGM1-conditioned media using a specific mouse MIP-1α ELISA (data not shown). After inoculation of 5TGM1 cells via tail veins, mice were randomized into groups and dosed for 4 weeks according to the protocol in Figure 1A. Because there was no statistically significant difference in the various parameters measured (including serum paraprotein titers) between the groups that received the vehicle and the isotype IgG, data from these 2 control tumor-bearing groups were pooled to allow stronger statistical analyses. Twice weekly administration of antimouse MIP-1α antibodies significantly reduced the number of lytic lesions and myeloma tumor burden in bones (determined on H&E-stained sections) compared with controls (Figure 1B). Not only were there fewer osteolytic lesions in tumor-bearing mice that received the antimouse MIP-1α antibodies, the lesions were also significantly smaller, with a 50% reduction in the mean surface area, compared with controls (data not shown). Treatment with anti-MIP-1α antibodies also resulted in a significant reduction in the frequency of splenomegaly in 5TGM1 myeloma-bearing mice. After 28 days, all 9 tumor-bearing control mice had enlarged spleens whereas only 4 of 10 tumor-bearing mice that received anti-MIP-1α antibodies had spleno megaly at the time of humane killing (Figure 1C). To determine whether neutralization of MIP-1α in vivo reduces myeloma tumor progression, titers of the monoclonal IgG2bκ paraprotein were determined in sera obtained from myeloma-bearing mice at killing. Treatment with anti-MIP-1α antibodies resulted in a significant reduction in serum IgG2bκ titers in 7 of 10 tumor-bearing mice (Figure 1D). Splenic wet weights correlated positively with serum IgG2bκ levels. Histomorphometric analyses of long bones and vertebrae revealed that blockade of MIP-1α function resulted not only in a reduction in tumor volume in bone but also a reduction in the number and intensity of staining of TRAP+ osteoclasts lining bone surfaces (Figure 2A-B).

CHO tumors secreting MIP-1α are associated with hypercalcemia, increased incidence, and significantly increased number of osteolytic lesions

To further investigate whether MIP-1α was sufficient to induce myeloma-like pathology in bone in vivo, stable clones of CHO cells were generated expressing human MIP-1α cDNA (CHO/MIP-1α cells). In initial experiments, we verified constitutive secretion of human MIP-1α by the CHO/MIP-1α cells in the conditioned media harvested from exponentially growing cells using a specific human MIP-1α ELISA with no mouse cross-reactivity (Figure 3A). Biologic activity of the secreted protein was further confirmed using the fetal rat long bone assay, an ex vivo bone organ culture system in which known resorptive factors induce bone resorption primarily through induction of osteoclastogenesis.36 Conditioned media from CHO/MIP-1α cells, but not media from CHO/EV cells, stimulated resorption of fetal rat calvariae (Figure 3B).

We next assessed the effect of human MIP-1α in an experimental setting designed to mimic a situation in which MIP-1α is present in the circulation. Because human MIP-1α signals through murine MIP-1α receptors, intramuscular tumors were induced in athymic mice by injection of either CHO/MIP-1α or CHO/EV cells into left thigh muscles. Tumors were restricted to thigh muscles, and there was no macroscopic evidence of metastases in any visceral organs. Development and progression of lytic lesions in long bones of the right (contralateral) hind limb were monitored by blinded image analysis of radiographs taken weekly. Only lesions visible in the contralateral hind limbs were quantified, because soft tissue masses of the rapidly growing intramuscular tumors precluded accurate determination of lesions on the ipsilateral limbs. All mice bearing CHO/MIP-1α tumors developed osteolytic lesions as early as 3 weeks after tumor inoculation, with the number of lesions in CHO/MIP-1α tumor-bearing mice increasing progressively up to 5 weeks (Figure 3C). In contrast, there were no lesions visible at earlier time points in mice bearing intramuscular CHO/EV tumors, and only 1 of the 5 mice bearing intramuscular CHO/EV tumors had any lesions after 5 weeks. There was also a progressive increase in the surface area of the lesions in the CHO/MIP-1α-bearing mice (from 0.118 ± 0.055 mm2 to 0.334 ± 0.107 mm2 at 3 and 5 weeks after tumor inoculation, respectively). No human MIP-1α was detectable in sera of CHO/MIP-1α tumor-bearing mice.

Because myeloma-induced osteolysis is due to factors acting locally in a paracrine and/or juxtacrine fashion, we sought to further assess the relevance of local MIP-1α production to myeloma-induced osteolysis. To this end, we utilized an experimental metastasis model in which tumors develop in the medullary cavities of long bones following systemic (intracardiac or intravenous) inoculation of CHO cells.37,38 Three weeks following inoculation of CHO/MIPα or CHO/EV cells into left ventricles of nude mice, there were significantly more radiographically visible lytic lesions in mice bearing CHO/MIP-1α tumors (Figure 4A-B), which also developed hypercalcemia (Figure 4C). Moreover, intramedullary CHO/MIP-1α tumors were associated with a global increase in intensity of TRAP staining and a significant increase in the number of TRAP+ osteoclasts at both tumor-bone and tumor-marrow interfaces compared with intramedullary CHO/EV tumors (Figure 4D-E). In CHO/MIP-1α tumors, the marked increase in osteoclast activity is evident even on the primary spongiosum side of the growth plate where no tumor is present. In contrast, in the CHO/EV tumors, no osteoclasts are present even where the tumor is closely apposed to the growth plate. As with mice bearing intramuscular CHO/EV tumors, no MIP-1α was detectable in sera of mice inoculated with tumor cells through the intracardiac route.

Recombinant MIP-1α stimulates osteoclast formation and bone resorption in vivo

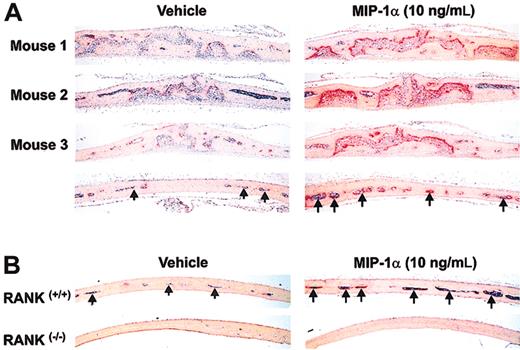

Finally, to assess the in vivo osteoclastogenic potential of MIP-1α directly, in separate experiments we injected either recombinant human or murine MIP-1α over the calvariae of normal mice. None of the treated mice exhibited overt signs of toxicity over the course of the experiment. There was a marked increase in the number of TRAP+ osteoclasts as well as marrow spaces (a measure of degree of resorption) in calvariae of mice injected with murine MIP-1α compared with saline controls (Figure 5A). There was a 2- to 3-fold increase in the number of osteoclasts when expressed per square millimeter of suture area or per millimeter of sutural bone perimeter (10 ng MIP-1α, 3.76 ± 0.84 versus saline control, 1.14 ± 0.28). Similar results were seen with human MIP-1α although murine MIP-1α was a log order more potent than human MIP-1α (data not shown). To test whether the in vivo osteoclastogenic effect of MIP-1α is dependent on signaling via RANK, we injected mouse MIP-1α (10 ng) directly over the calvariae of RANK-/- mice and wild-type littermates. Whereas MIP-1α induced osteoclast formation and increased the number of marrow spaces in the wild-type RANK+/+ mice, it had no effect in RANK-/- mice (Figure 5B). There was a complete absence of marrow spaces in RANK-/- calvariae as a consequence of the complete lack of osteoclasts and resorptive activity. This was unaffected by MIP-1α administration.

Recombinant MIP-1α induces osteoclast formation and bone resorption in vivo via RANK ligand (RANKL)/RANK signaling pathway. (A) Injection of 10 ng MIP-1α daily for 5 days into supracalvarial subcutaneous tissues in normal Swiss ICR mice resulted in a significantly increased number of osteoclasts (TRAP+; pink/red stained) and marrow spaces (arrows) compared with saline controls. Representative sections of calvariae from 3 separate mice are shown (each of the top 3 panels on either side represents the midsagittal suture area of calvaria of one mouse; bottom panels represent the region of calvariae away from the midline). (B) Although injection of MIP-1α induced osteoclast formation and bone resorption, represented by increased marrow spaces (arrows) in calvariae of wild-type litter-mates, it had no effect in RANK null mutant mice. Note lack of marrow spaces and bowing of calvariae of RANK-/- mice due to absence of osteoclasts.

Recombinant MIP-1α induces osteoclast formation and bone resorption in vivo via RANK ligand (RANKL)/RANK signaling pathway. (A) Injection of 10 ng MIP-1α daily for 5 days into supracalvarial subcutaneous tissues in normal Swiss ICR mice resulted in a significantly increased number of osteoclasts (TRAP+; pink/red stained) and marrow spaces (arrows) compared with saline controls. Representative sections of calvariae from 3 separate mice are shown (each of the top 3 panels on either side represents the midsagittal suture area of calvaria of one mouse; bottom panels represent the region of calvariae away from the midline). (B) Although injection of MIP-1α induced osteoclast formation and bone resorption, represented by increased marrow spaces (arrows) in calvariae of wild-type litter-mates, it had no effect in RANK null mutant mice. Note lack of marrow spaces and bowing of calvariae of RANK-/- mice due to absence of osteoclasts.

Discussion

At present, it is unclear how MIP-1α influences osteoclastic bone resorption in myeloma. MIP-1α is produced excessively by freshly isolated malignant plasma cells from patients and human myeloma cell lines11-13 and is present in the bone marrow and marrow supernatants of myeloma patients with bone disease at much higher levels compared with patients with no bone disease and those with other hematologic malignancies and normal controls.11-14 It was surmised that the chemokine may play a role as a mediator in the bone disease associated with myeloma,11-13 because MIP-1α stimulates not only chemotaxis of monocyte-macrophage lineage cells (including osteoclast precursors and mature osteoclasts)15,17,18 but also osteoclastic differentiation and resorption in vitro.15,19,20,21 Here we show that functional blockade of MIP-1α bioactivity with neutralizing anti-MIP-1α antibodies attenuates tumor-induced lytic bone lesions in murine 5TGM1 myeloma-bearing mice, consistent with the notion that the chemokine plays an important role in the osteolysis associated with myeloma in vivo. Surprisingly, we also found a concomitant decrease in overall tumor burden, suggesting a previously unrecognized effect of MIP-1α on myeloma tumor progression. We also demonstrate in a variety of experimental model systems the osteoclastogenic nature of MIP-1α when expressed adjacent to bone surfaces in vivo.

An unexpected finding in our study was the increased incidence and size of radiologically identifiable lytic lesions, which was confirmed histologically, in long bones of contralateral hind limbs of mice bearing intramuscular human MIP-1α-expressing CHO tumors. In addition, the osteolytic lesions developed at a much faster rate in CHO/MIP-1α tumor-bearing mice compared with CHO/EV tumor-bearing mice. Mock- or empty vector-transfected CHO cells possess the capacity to metastasize to bone when inoculated into left ventricles of mice.38 However, previous studies by our group have shown that when CHO cells are inoculated intramuscularly or subcutaneously, only a small number of these cells leave the primary tumor site and metastasize to other tissues.39-42 In these settings, metastatic bone lesions are uncommon presumably because a significant proportion of the migrating cells arrest in the pulmonary bed. Because naive CHO cells cannot respond to MIP-1α and need to be transfected with either CCR1 or CCR5 for intracellular calcium signaling to be activated or for the cells to migrate in response to MIP-1α (data not shown), this rules out the possibility that the increased lesions in the hind limbs contralateral to those bearing intramuscular CHO/MIP-1α tumors are due to secreted MIP-1α acting in an autocrine fashion to facilitate tumor cell trafficking to distant skeletal sites. It is highly likely that CHO cells detach equally from the intramuscular CHO/MIP-1α tumors as well as the CHO/EV tumors and migrate to reach bone. We speculate that once the tumor cells arrive in the medullary cavity, MIP-1α secreted by the CHO/MIP-1α cells alters the bone marrow microenvironment, enabling the tumor cells to set up residence efficiently, grow, and form new tumors or lytic lesions, thus inducing pathology. In contrast, empty vector-transfected CHO cells, which do not constitutively produce MIP-1α, are unable to settle and grow in bone. In support of this notion, there is evidence that MIP-1α activates integrins such as α4 on tumor-associated macrophages in an autocrine fashion and this in turn triggers cell-cell adhesion.43 Increased expression and/or activation of α4 integrin correlates with development of experimental bone metastases, and nude mice inoculated with CHO cells expressing human α4 integrin form more lytic bone lesions than those inoculated with empty vector-transfected controls.37 With regard to myeloma, we and others have shown that human and murine myeloma cells including 5TGM1 cells express the α4 integrin constitutively.44,45 MIP-1α signals through at least 2 cell surface receptors, CCR1 and CCR5,1,4 both of which are expressed by primary human myeloma cells as well as human myeloma cell lines.12,46,47 In addition, we have found by RT-PCR that 5TGM1 cells express messenger RNA for mouse CCR1 (data not shown). Thus, MIP-1α may have previously unidentified autocrine effects on malignant plasma cells, including activation of α4 integrin, as has been reported for tumor-derived cells.43 In this regard, it has recently been reported that MIP-1α triggers migration, induces proliferation, and promotes survival of purified myeloma cells from a patient as well as human myeloma cell lines in vitro.47 MIP-1α activated multiple signaling pathways known to mediate proliferation and to protect against apoptosis cells but did not induce secretion of known growth/survival factors for myeloma cells.47 This suggests that the effect of the chemokine, at least in a subset of malignant plasma cells, may be direct. However, because we found no effect of MIP-1α on proliferation of 5TGM1 myeloma cells (data not shown), more complex and indirect interactions of the chemokine in myeloma cannot be excluded. In vivo and in vitro, myeloma cells adhere avidly to bone marrow stromal cells and osteoblasts via α4β1 (very late antigen-4 [VLA4]) receptor binding its cognate ligand vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) on the bone cells, and this interaction may require continuous activation of VLA4 by MIP-1α. Importantly, evidence is accruing that signaling cascades activated by VCAM-1-VLA4 interactions also contribute to growth and survival of myeloma cells and are in part responsible for the increased osteoclast formation and bone resorption in myeloma.44,48

There is a substantial body of evidence indicating that osteoclast formation and bone resorption in vivo are mediated via RANK ligand (RANKL) signaling through its cognate receptor RANK on osteoclasts and their precursors. Consistent with this notion, mice with genetically engineered deletion of the RANKL or RANK gene are profoundly osteopetrotic. RANK is the only known receptor through which RANKL signals. RANKL mediates the effects of most of the known osteoclastogenic cytokines as their effects are abrogated in RANK or RANKL knock-out mice.49 Although MIP-1α significantly enhances the effect of RANKL to induce formation of TRAP+ multinucleated cells in cultures of RAW264.7 preosteoclastic cells in the absence of bone marrow stromal/osteoblastic cells, it does not by itself promote osteoclastic differentiation (data not shown). It is therefore likely that the predominant osteoclastogenic effect of MIP-1α in bone is exerted indirectly via RANKL-expressing cells in bone such as marrow stromal cells, osteoblasts, or endothelial cells. However, there are conflicting data on the effect of MIP-1α on RANKL expression, with one group reporting that MIP-1α stimulates RANKL expression by bone marrow-derived stromal cells in vitro12 and others suggesting that the osteoclastogenic effect of MIP-1α in vitro is RANKL independent.16 The reason for this discrepancy is unknown. To clarify this, we performed in vivo experiments injecting MIP-1α over the calvariae of RANK-/- mice. In contrast to its marked osteoclastogenic effect in normal mice, MIP-1α had no effect in RANK-/- mice, strongly suggesting that an intact RANK signaling pathway is required for the in vivo osteoclastogenic effect of the chemokine to manifest. Although it could be argued that our data with the RANK knock-out mice do not unequivocally exclude MIP-1α acting via a RANKL-independent pathway, to date no other cognate ligands for RANK have been identified. Osteoprotegerin, the naturally occurring soluble decoy receptor for RANKL, almost completely abrogated MIP-1α-induced osteoclast formation in vitro.12 We and others have previously shown that RANK.Fc, a genetically engineered antagonist of RANKL bioactivity and potent inhibitor of osteoclast activity in vivo,34 attenuates tumor-induced osteolysis in different mouse models of human myeloma.50-52 Based on this, we propose that RANKL is the final common mediator of osteoclastogenesis and bone resorptive activity in myeloma in vivo, and the data herein provide strong support for that notion.

An antimyeloma effect similar to what we observed in this study with anti-MIP-1α antibodies has previously been seen with RANK.Fc in our 5TGM1 model as well as the SCID-hu myeloma model.50,51 It is unclear, in either case, whether this represents a direct antitumor effect or a secondary response to the marked inhibition of osteoclastic activity and/or alteration of the bone microenvironment. The extraskeletal response to disruption of MIP-1α bioactivity in the 5TGM1 model such as the decreased splenomegaly argues against this being a consequence of the latter. Moreover, we have previously shown that complete inhibition of osteoclastic activity achieved by treatment with ibandronate, a potent nitrogen-containing bisphosphonate (N-BP), does not reduce tumor burden in bone in the 5TGM1 model.29 Nevertheless, in the SCID-hu model, zoledronic acid, another potent N-BP, was shown to reduce tumor burden.52 The reason for this difference is presently unclear.

It was recently reported that inhibiting MIP-1α production using an antisense approach also impairs development and progression of bone disease in a model in which ARH-77 human B-lymphoblastoid cells inoculated in irradiated SCID mice induce osteolysis and extensive extramedullary disease.21 There is controversy as to whether the ARH-77/SCID model is a true myeloma model. Although originally derived from a patient with plasma cell leukemia, the ARH-77 cell line is most probably an Epstein-Barr virus-positive B-lymphoblastoid cell line (EBV+ BLCL) and not a true myeloma cell line.53 Although ARH-77 cells are capable of inducing osteolysis in vivo, independent extensive molecular characterization and immunophenotyping have shown that the ARH-77 cell line and other EBV+ BLCLs are indeed very different from authentic myeloma cell lines.53-55 Nevertheless, ARH-77 cells produce substantial amounts of MIP-1α. Transfection of antisense constructs into ARH-77 cells resulted in significantly lower MIP-1α production and, consistent with our results, there were no radiologically evident lytic lesions in bone when these cells were grafted into SCID mice. This confirms that MIP-1α is a necessary factor in inducing myeloma-like lytic lesions in vivo. As mentioned earlier, CHO cells do not produce appreciable amounts of MIP-1α in the basal state. Importantly, when we inoculated CHO cells engineered to express and secrete human MIP-1α into nude mice, multiple lytic bone lesions similar to those seen in myeloma developed. Inoculation of empty vector-transfected cells into mice did not have this effect, indicating that MIP-1α may be sufficient to induce skeletal pathology with features similar to those that are characteristic of myeloma.

The present study suggests that by modulating not only the tumor but also its microenvironment, therapeutic strategies aimed at neutralizing MIP-1α bioactivity in vivo may be beneficial adjuncts in the clinical management of myeloma-associated bone disease and possibly myeloma itself. Although the use of neutralizing antibodies in patients is not likely to be feasible, nonpeptidic small molecule MIP-1α receptor antagonists could be used readily to disrupt MIP-1α-initiated signaling. Of the 2 well-established signaling receptors for MIP-1α, CCR5 but not CCR1 also mediates the effects of MIP-1β, a highly homologous but distinct CC chemokine.1,5 Because the neutralizing anti-MIP-1α antibodies did not completely block myeloma growth and osteolysis, a role for MIP-1β in myeloma development and progression cannot be unequivocally excluded. Although it is presently unclear which receptor mediates the osteoclastogenic effects of MIP-1α in vivo, it is likely that CCR5 is involved, because intramuscular implantation of CHO cells engineered to secrete MIP-1β in nude mice also induces osteolytic lesions (data not shown). This is consistent with recent reports that neutralizing antibodies against CCR5 block formation of osteoclast-like cells induced by myeloma cell-conditioned media in cocultures of osteoclast precursors and marrow stromal cells. Importantly, neutralizing antibodies directed against MIP-1α or MIP-1β mimicked this effect of anti-CCR5 antibodies.12

Multiple myeloma cannot be cured by standard chemotherapeutic approaches, and the high morbidity and mortality associated with this malignancy are mainly due to complications of osteoclast-mediated bone destruction.10 Although much progress has been made recently in the therapeutic use of N-BPs for cancer-induced osteolysis, this has not resulted in significantly improved clinical outcomes in myeloma patients. Understanding the pathophysiology of myeloma progression and associated bone destruction is key to identification of new interventions that may concomitantly impact tumor burden and reduce further bone loss, thereby improving the quality of life of patients.

In summary, the data presented in this report strongly suggest that MIP-1α impacts both osteoclasts and tumor cells in myeloma. We surmise that production of MIP-1α in the bone milieu is necessary to induce myelomatous lesions and that further investigation of the antitumor and antiosteolytic efficacy of MIP-1α receptor antagonists in valid preclinical models of myeloma would thus be worthwhile. Potent and orally bioavailable, synthetic small molecule antagonists of both CCR1 and CCR5 are already available, under development for other disease conditions.56,57

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, March 20, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3905.

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (PO1-CA40035 and RO1-AI29110 to G.R.M. and B.S., respectively) and funds from the UTHSCSA Howard Hughes Medical Institute Research Resources Program (B.O.O.). B.O.O. was a recipient of a Brian D. Novis research award from the International Myeloma Foundation and a Fellow's Research Award from The Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked ”advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We are grateful to Beryl Story for technical assistance with histology, to Rami Käkönen and Nancy Place for assistance with preparation of figures, and to Dr Larry Swain for critical review of the manuscript.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal