Abstract

Arsenic can induce apoptosis and is an efficient drug for the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Currently, clinical studies are investigating arsenic as a therapeutic agent for a variety of malignancies. In this study, Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cell lines served as model systems to characterize the role of nuclear factor–κB (NF-κB) in arsenic-induced apoptosis. Arsenic rapidly down-regulated constitutive IκB kinase (IKK) as well as NF-κB activity and induced apoptosis in HRS cell lines containing functional IκB proteins. In these cell lines, apoptosis was blocked by inhibition of caspase-8 and caspase-3–like activity. Furthermore, arsenic treatment down-regulated NF-κB target genes, including tumor necrosis factor-αreceptor–associated factor 1 (TRAF1), c-IAP2, interleukin-13 (IL-13), and CCR7. In contrast, cell lines with mutated, functionally inactive IκB proteins or with a weak constitutive IKK/NF-κB activity showed no alteration of the NF-κB activity and were resistant to arsenic-induced apoptosis. A direct role of the NF-κB pathway in arsenic-induced apoptosis is shown by transient overexpression of NF-κB–p65 in L540Cy HRS cells, which protected the cells from arsenic-induced apoptosis. In addition, treatment of NOD/SCID mice with arsenic trioxide induced a dramatic reduction of xenotransplanted L540Cy Hodgkin tumors concomitant with NF-κB inhibition. We conclude that inhibition of NF-κB contributes to arsenic-induced apoptosis. Furthermore, pharmacologic inhibition of the IKK/NF-κB activity might be a powerful treatment option for Hodgkin lymphoma.

Introduction

Although organic and inorganic arsenic-containing compounds are environmental toxins, they have been used for more than 100 years for the treatment of human diseases.1,2 Salvarsan, active against syphilis,3 or melarsoprol, still used for the treatment of African sleeping sickness,4 are examples of organic arsenicals. Fowler solution, which was used for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia5 (CML) or psoriasis,6 is an example of inorganic arsenic. Most of these drugs have been replaced by others, as it became clear that arsenic causes diverse pathologies and increases the risk of cancer.7,8 Since the discovery that arsenic trioxide (As2O3) is an efficient drug for the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia9 (APL), As2O3 was reintroduced in current therapeutic concepts. Initial clinical studies focused on the treatment of hematopoietic malignancies. Currently, the action of arsenic on many other tumor entities is under investigation.10,11

Depending on the cell type and the applied concentrations of arsenic, diverse cellular effects are observed (for a recent review, see Miller et al12 ). Low concentrations can induce differentiation or cell cycle arrest, whereas high concentrations can induce apoptosis. Mechanisms leading to induction of apoptosis were extensively studied. An important role was attributed to arsenic-triggered degradation of specific proteins with prosurvival function. The strongest correlation was found with the degradation of the promyelocytic leukemia/retinoic acid receptor-α (PML/RAR-α) protein in APL,13 but also degradation of the viral Tax protein in human T-cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV)–induced T-cell leukemia has been reported.14 However, these mechanisms cannot explain the induction of apoptosis in many other cell types. As a general finding, all 3 groups of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), p38, and Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), are activated in response to arsenic.15,16 This activation may be responsible for the carcinogenic effects of arsenic, but MAPK activation is not required for arsenic-induced apoptosis.17 Furthermore, the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) has been implicated in arsenic-mediated apoptosis.18

The biologic effects of arsenic may be attributed to structural and functional alterations of critical cellular proteins by its reactivity with sulfhydryl groups.19 The resulting loss of function of specific enzymes, including kinases and phosphatases, functionally alters diverse signaling pathways. For example, arsenic-mediated inhibition of MAPK phosphatases, which contain cysteines in their catalytic pocket, induces MAPK activation.16 Arsenic exerts an opposite effect on the IκB kinase (IKK) complex.20 The IKK complex, which is composed of the 2 catalytic IKKα and IKKβ subunits and the regulatory IKKγ/NEMO component, is the central mediator of nuclear factor–κB (NF-κB)–inducing stimuli.21 Activation of the IKK complex results in phosphorylation of IκBs, which subsequently are ubiquitinylated and degraded by the proteasome. The degradation of IκBs allows transient translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus.22 In vitro, arsenic interacts with a cysteine in the activation loop of IKKβ, the kinase critically involved in transient NF-κB activation. Thus, treatment of cells with arsenic inhibits transient NF-κB activation by various stimuli due to blocked IKKβ activation.20

In contrast to transient NF-κB activation, constitutively activated NF-κB is a characteristic feature of different tumor entities.23 It was first shown for Hodgkin lymphoma that constitutive NF-κB is required for growth and survival of the tumor cells.24,25 Molecular defects in the signaling cascade leading to activation of NF-κB may contribute to the constitutive NF-κB activity of the malignant Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells. Mutated IκBα and IκBϵ proteins in HRS cells are unable to bind and to retain NF-κB in the cytoplasm due to a partial loss of the ankyrin repeat domain or C-terminal truncations.26,27 Furthermore, the IKK complex in HRS cell lines is constitutively activated, as reflected by the rapid turnover of IκBs.28 Meanwhile, it was suggested that constitutive IKK/NF-κB activity is a survival factor for a growing number of tumor entities.23 Pharmacologic inhibition of constitutive IKK/NF-κB activity might thus be a powerful treatment option for these tumors, including Hodgkin lymphoma.

The aim of our study was to investigate whether arsenic modulates constitutive IKK/NF-κB activity in HRS cells and whether IKK/NF-κB inhibition contributes to arsenic-induced apoptosis. We report that sodium arsenite (NaAsO2) and arsenic trioxide (As2O3) strongly inhibit constitutive IKK and NF-κB activity in HRS cell lines and down-regulate NF-κB–dependent target genes, among these tumor necrosis factor-α receptor–associated factor 1 (TRAF1), c-IAP2, interleukin-13 (IL-13), and CCR7. In these cell line models, inhibition of constitutively active NF-κB correlates with arsenic-induced apoptosis. That NF-κB inhibition is indeed involved in apoptosis induction by arsenic is directly shown by overexpression of NF-κB–p65, which rescues HRS cells from arsenic-induced apoptosis. In a nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD/SCID) mouse model, arsenic trioxide down-regulates NF-κB and induces a dramatic response in L540Cy xenotransplanted Hodgkin tumor cells, confirming the in vitro data.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture conditions

The HRS cell lines L428, L1236, KMH-2, HDLM-2, L540, L540Cy (kindly provided by A. Engert, University Hospital Cologne, Germany), and HD-MyZ were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Seromed-Biochrom, Hamburg, Germany) at 37°C and 5% CO2 as described.29 Cells were treated with NaAsO2 (sodium arsenite; Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) or As2O3 (arsenic trioxide; Sigma), where indicated. NaAsO2 and As2O3 were dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4; for both substances a 10 mM stock solution was prepared. Electroporation of L540Cy cells was performed using a Gene-Pulser II (Bio-Rad, München, Germany) with 960 microfarads (μF) and 0.18 kV. Transfection-associated cell death was negligible. The following expression plasmids were used: p65-pEGFP (kindly provided by J. Schmid, Vienna, Austria), pcDNA3 (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany), and pEGFP-N3 (Clontech Laboratories, Heidelberg, Germany). Cells were transfected with 40 μg p65-GFP expression plasmid or 36 μg pcDNA3 along with 4 μg pEGFP-N3 plasmid.

Induction and analysis of apoptosis

Apoptotic cells were detected using the following methods. Cells were stained with acridine orange (5 μg/mL; Sigma) and observed by fluorescence microscopy. The number of cells revealing fragmented or condensed nuclei were enumerated. Alternatively, cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) (Bender MedSystems, Vienna, Austria) according to the manufacturer's recommendation. Samples were analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer and CELLQuest software (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany). Caspase activity was blocked using the cell-permeable irreversible caspase-8 inhibitor z-IETD-fmk and the caspase-3 family inhibitor z-DEVD-fmk (both from Calbiochem, Bad Soden, Germany). Prior to treatment with arsenite, cells were preincubated for 30 minutes with different concentrations of the caspase inhibitors. All assays were performed in triplicate. In the case of green fluorescent protein (GFP) cotransfected cells, the percentage of viable and late apoptotic cells was determined by PI staining and subsequent FACS analysis.

Protein preparation and immunoblotting

Cells from different time points after the induction of apoptosis were washed twice in PBS. Whole cell extracts were prepared as described.29 Protein samples (20 μg per lane) were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto nitrocellulose filters (Schleicher and Schuell, Dassel, Germany). The filters were blocked (1% nonfat dry milk, 0.1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris [tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane] [pH 7.5]) and incubated with the following 1:1000 diluted primary antibodies: polyclonal anti-IκBα, monoclonal anti-TRAF1, polyclonal anti-p65, polyclonal anti–polyadenosine-5′-diphosphate-ribose polymerase (anti-PARP) (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany), polyclonal anti–c-IAP2 (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD), polyclonal anti–Bcl-xL (Transduction Laboratories, Heidelberg, Germany), polyclonal anticaspase-3, and monoclonal anti-IKKα (both from Pharmingen, Heidelberg, Germany). Filters were incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies. Bands were visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and whole cell extract preparation were described previously.29

IκB kinase assay

For the analysis of IκB kinase activity, cells were left untreated or treated with different concentrations of arsenite. After washing with PBS, extracts were prepared using lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES [N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid] [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA [ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid], 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 1 μg/mL Pefabloc (4-(2-aminoethyl)-benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride), aprotinin, and leupeptin, respectively, 10 mM NaF, 8 mM β-glycerophosphate, 100 μM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]). A total of 250 μg of each extract was precleared for 30 minutes at 4°C with protein A–Sepharose beads (Amersham). For immunoprecipitation, protein A–Sepharose beads and 1 μg monoclonal anti-IKKα antibody (Pharmingen) were added for 2 hours at 4°C. The protein A–Sepharose was washed 4 times with lysis buffer and once with kinase buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 10 mM MgCl2, 20 μM adenosine triphosphate [ATP], 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 μM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM DTT). Thereafter, 20 μL kinase buffer, 1 μg purified recombinant glutathione-S-transferase–IκBα (GST-IκBα) (amino acids [aa] 1 to 53), and 3 μCi (0.111 MBq) [γ-32P]ATP were added to the protein A–Sepharose immunecomplex. The kinase reaction was incubated for 20 minutes at 37°C. Reaction mixtures were boiled and subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

Northern blot analysis

Total RNA was prepared using the RNeasy kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). 10 μg total RNA was subjected to gel electrophoresis on a 1.1% formaldehyde–1.2% agarose gel and transferred to a nylon membrane (Appligene, Heidelberg, Germany). After UV cross-linking, the membrane was prehybridized (ExpressHyb solution, Clontech) and thereafter hybridized with [α-32P]deoxycytidine triphosphate ([α-32P]dCTP)–labeled random prime-labeled DNA probes (IκBα, IL-13, CCR7, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase [GAPDH]) overnight at 68°C. Membranes were washed at room temperature in 2 × SSC and 0.05% SDS and then in 0.1 × SSC and 0.1% SDS.

NOD/SCID mice experiments

All animal experiments were performed by EPO (Berlin, Germany) according to the German Animal Protection Law with permit of the responsible authorities. L540Cy or HD-MyZ HRS cells were xenotrans-planted into NOD/SCID mice, which were maintained in a pathogen-free environment under standardized environmental conditions. Tumors were measured in 2 dimensions, length (a) and width (b), by use of calipers. Tumor volume (V) was calculated according to the formula V = ab2/2. In the first experiment, 107 L540Cy cells were inoculated subcutaneously. Mice were divided into 2 groups, when tumors were palpable. Group 1 (n = 6) was treated intravenously with PBS alone and group 2 (n = 6) with 3.75 mg/kg/d As2O3 on days 3 to 17 and 7.5 mg/kg/d on days 18 to 25. Mice with a tumor burden more than 1 cm3 were killed on day 28. For in vitro analysis of cells from tumors in mice, 2 mice of the control group were treated on day 28 with PBS, and 2 mice were treated with 7.5 mg/kg As2O3. After 6 hours, the mice were killed. The tumors were explanted, and whole cell extracts of the tumor material were prepared. In the second experiment, 107 L540Cy or HD-MyZ cells were inoculated subcutaneously. Mice were divided into 3 groups, when tumors were palpable. Group 1 (n = 6) was treated intravenously with PBS alone, group 2 (n = 6) received 5 mg/kg/d, and group 3 (n = 6) 7.5 mg/kg/d As2O3 intravenously. The in vitro analysis of tumor cells was as described above.

Results

Arsenite inhibits constitutively active NF-κB due to inhibition of the IKK complex

HRS cell lines were used as a model system to investigate effects of arsenic on constitutive IKK/NF-κB activity. In the HRS cell lines HDLM-2, L1236, L540, and L540Cy, a subclone of the cell line L540, which grows in SCID mice, sodium arsenite (NaAsO2) inhibited NF-κB DNA binding activity (Figure 1A and data not shown). Eight hours of incubation with 50 to 200 μM arsenic blocked the NF-κB activity almost completely. Because clinically obtainable serum concentrations of arsenic are 2 to 5 μM,30 we analyzed effects of these concentrations on HRS cell lines (Figure 1A and data not shown). Prolonged incubation of L540 or HDLM-2 cells with 1 to 5 μM NaAsO2 clearly reduced constitutive NF-κB activity after 24 to 48 hours. Because IκBα is the main target of the IKK complex, which is inhibited by arsenite,20 we analyzed IκBα protein and mRNA expression levels in response to arsenite (Figure 1B). Whereas the IκBα protein level increased or remained at least unaltered, the IκBα mRNA level dropped, as IκBα itself is transcriptionally regulated by NF-κB. This indicated a posttranslational stabilization of the protein, which is consistent with reduced IKK activity. Indeed, incubation of HRS cells with both high and low concentrations of NaAsO2 reduced IKK activity, as measured by in vitro kinase assays (Figure 1C). In contrast, all 3 groups of MAPKs (ERK1/2, p38, and JNK) were activated by arsenite (data not shown).

Inhibition of NF-κB and IKK activity by NaAsO2(A) HDLM-2 and L1236 cells were treated for 8 hours and L540 cells for 48 hours with the indicated concentrations of NaAsO2. Whole cell extracts were analyzed by EMSA for NF-κB DNA binding activity. Free DNA probe is not shown; n.s. indicates nonspecific. (B) Expression level of IκBαmRNA and protein in response to NaAsO2. After incubation of HDLM-2 and L1236 cells for 8 hours with the indicated concentrations of NaAsO2, whole cell extracts were analyzed for IκBαprotein expression by Western blot analysis (WB, upper 2 blots). Total mRNA was prepared after 8 hours and analyzed for expression of IκBαand GAPDH by Northern blotting (NB, lower 4 blots). (C) Arsenite-mediated IKK inhibition. HDLM-2 cells were treated for 8 hours with PBS or 50 μM NaAsO2, or for 48 hours with 1 to 5 μM NaAsO2, as indicated. IKK activity was determined by an in vitro kinase assay (KA). IKKαwas immunoprecipitated using a monoclonal antibody against IKKαand protein A–Sepharose. The precipitates were incubated with IκBαand [γ-32P]ATP at 37°C and subsequently analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. As control, IKKαexpression was analyzed by Western blotting.

Inhibition of NF-κB and IKK activity by NaAsO2(A) HDLM-2 and L1236 cells were treated for 8 hours and L540 cells for 48 hours with the indicated concentrations of NaAsO2. Whole cell extracts were analyzed by EMSA for NF-κB DNA binding activity. Free DNA probe is not shown; n.s. indicates nonspecific. (B) Expression level of IκBαmRNA and protein in response to NaAsO2. After incubation of HDLM-2 and L1236 cells for 8 hours with the indicated concentrations of NaAsO2, whole cell extracts were analyzed for IκBαprotein expression by Western blot analysis (WB, upper 2 blots). Total mRNA was prepared after 8 hours and analyzed for expression of IκBαand GAPDH by Northern blotting (NB, lower 4 blots). (C) Arsenite-mediated IKK inhibition. HDLM-2 cells were treated for 8 hours with PBS or 50 μM NaAsO2, or for 48 hours with 1 to 5 μM NaAsO2, as indicated. IKK activity was determined by an in vitro kinase assay (KA). IKKαwas immunoprecipitated using a monoclonal antibody against IKKαand protein A–Sepharose. The precipitates were incubated with IκBαand [γ-32P]ATP at 37°C and subsequently analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. As control, IKKαexpression was analyzed by Western blotting.

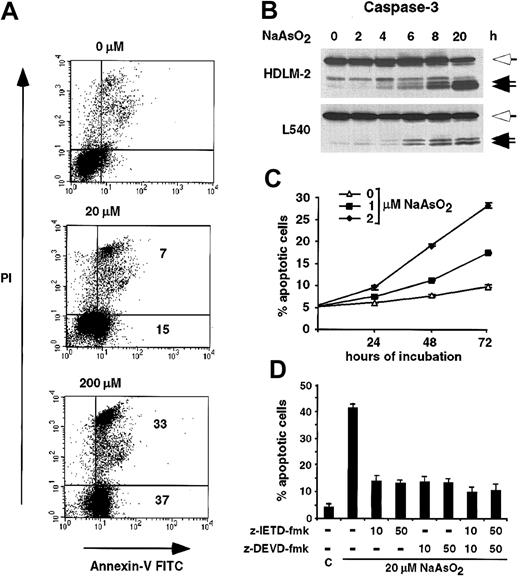

Induction of apoptosis by arsenite in vitro

Recent data show that inhibition of NF-κB by the superrepressor IκBα▵N induces apoptosis of HRS cell lines.31,32 In line with these data, arsenite induced apoptosis in the HRS cell lines L540, HDLM-2, and L1236 (Figure 2A and data not shown). Treatment of the cell line L540 with 20 μM and 200 μM arsenite induced apoptosis in 22% and 70% of the cells after 20 hours (annexin V+ and PI+); 15% and 37% were early apoptotic cells (annexin V+ and PI-). Activation of caspase-3 was detected by Western blot analysis, confirming apoptosis induction (Figure 2B). Consistent with the inhibition of the IKK/NF-κB activity by low concentrations of arsenic, prolonged incubation of the cell lines HDLM-2 or L540 with 1 or 2 μM arsenite induced apoptosis (Figure 2C and data not shown). After 72 hours of incubation with 2 μM arsenite, approximately 25% to 30% of the HDLM-2 cells showed characteristic features of apoptosis.

Induction of apoptosis by NaAsO2 in HRS cell lines.(A) L540 cells were incubated for 20 hours with 0, 20, or 200 μM NaAsO2, as indicated. Cells were stained with annexin V–FITC and PI and analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis. The percentage of annexin V+ cells relative to the untreated cells is indicated. (B) HDLM-2 and L540 cells were treated with 20 μM arsenite. At the indicated times whole cell lysates were prepared and analyzed for cleavage of caspase-3 by Western blotting. The full-length protein (open arrows) and the cleavage products (closed arrows) are indicated. (C) HDLM-2 cells were treated with 0 (▵), 1 (▪), or 2 (⋄) μM NaAsO2. After 24, 48, and 72 hours, the fraction of annexin V–FITC+ cells was determined by FACS analysis. Error bars denote SDs. (D) Inhibition of NaAsO2-induced apoptosis by blockage of caspase-8– or caspase-3–like activity. Prior to the incubation with 20 μM NaAsO2, HDLM-2 cells were treated with various concentrations of the caspase-8 inhibitor z-IETD-fmk and/or the caspase-3 family inhibitor z-DEVD-fmk, or, as control (C), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) alone. After 20 hours of treatment with NaAsO2, the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by acridine orange staining. Error bars denote SDs.

Induction of apoptosis by NaAsO2 in HRS cell lines.(A) L540 cells were incubated for 20 hours with 0, 20, or 200 μM NaAsO2, as indicated. Cells were stained with annexin V–FITC and PI and analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis. The percentage of annexin V+ cells relative to the untreated cells is indicated. (B) HDLM-2 and L540 cells were treated with 20 μM arsenite. At the indicated times whole cell lysates were prepared and analyzed for cleavage of caspase-3 by Western blotting. The full-length protein (open arrows) and the cleavage products (closed arrows) are indicated. (C) HDLM-2 cells were treated with 0 (▵), 1 (▪), or 2 (⋄) μM NaAsO2. After 24, 48, and 72 hours, the fraction of annexin V–FITC+ cells was determined by FACS analysis. Error bars denote SDs. (D) Inhibition of NaAsO2-induced apoptosis by blockage of caspase-8– or caspase-3–like activity. Prior to the incubation with 20 μM NaAsO2, HDLM-2 cells were treated with various concentrations of the caspase-8 inhibitor z-IETD-fmk and/or the caspase-3 family inhibitor z-DEVD-fmk, or, as control (C), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) alone. After 20 hours of treatment with NaAsO2, the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by acridine orange staining. Error bars denote SDs.

Arsenite-induced apoptosis involves activation of caspase-8

NF-κB is known to protect cells against apoptotic stimuli such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) by inhibition upstream of the caspase cascade.33 We therefore analyzed the role of caspase-8, which plays a major role in this process, in arsenite-mediated apoptosis (Figure 2D). Inhibition of caspase-8 activity by the irreversible inhibitor z-IETD-fmk blocked arsenite-induced apoptosis in the cell line HDLM-2. Inhibition of caspase-3–like activity by the irreversible inhibitor z-DEVD-fmk did not further inhibit arsenite-induced apoptosis. Importantly, treatment of the cells with both inhibitors together blocked apoptosis only marginally better than z-IETD-fmk alone. These data suggest that arsenite-induced apoptosis depends on the activation of caspase-8. Inhibition of caspase activity was also analyzed by detection of PARP cleavage, showing PARP cleavage only after treatment with arsenite alone (data not shown).

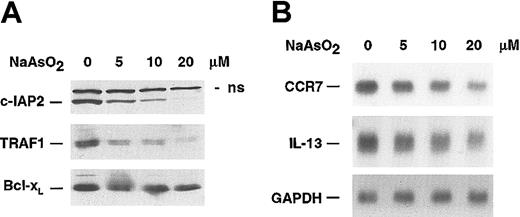

Down-regulation of NF-κB–dependent target genes in response to arsenite

NF-κB maintains in HRS cells a high expression level of genes involved in cell-cycle regulation and apoptosis, among these a number of antiapoptotic genes.31,32 Therefore, we analyzed arsenite-dependent alterations of the protein level of c-IAP2, TRAF1, and Bcl-xL, all of them defined as NF-κB–dependent genes in HRS cells. Consistent with the arsenic-induced inhibition of NF-κB, a strong decrease of c-IAP2 and TRAF1 protein expression was observed, whereas Bcl-xL expression dropped slightly (Figure 3A). In addition, CCR7 and IL-13, which are both strongly expressed in HRS cells and newly identified NF-κB–dependent target genes,32,34 showed a down-regulation of their respective mRNAs (Figure 3B).

Regulation of NF-κB–dependent target genes by NaAsO2 HDLM-2 cells were treated for 20 hours with the indicated concentrations of NaAsO2. (A) Whole cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting for the expression of c-IAP2, TRAF1, and Bcl-xL; n.s. indicates nonspecific. (B) Total mRNA was analyzed by Northern blotting for expression of CCR7, IL-13, and GAPDH.

Regulation of NF-κB–dependent target genes by NaAsO2 HDLM-2 cells were treated for 20 hours with the indicated concentrations of NaAsO2. (A) Whole cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting for the expression of c-IAP2, TRAF1, and Bcl-xL; n.s. indicates nonspecific. (B) Total mRNA was analyzed by Northern blotting for expression of CCR7, IL-13, and GAPDH.

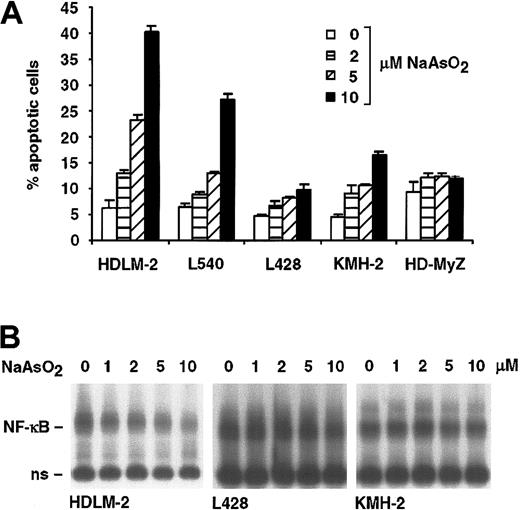

Arsenite-induced apoptosis is dependent on functional IκB proteins as well as on the inhibition of NF-κB activity

Different mutations of the IκB proteins as well as different IKK and NF-κB activity in HRS cell lines25-27 (Table 1) allow an analysis of the involvement of the IKK/NF-κB system in arsenic-induced apoptosis. HDLM-2, L540, L1236, and HD-MyZ cells express wild-type IκB proteins, whereas KMH-2 cells lack functional IκBα and L428 cells lack functional IκBα and IκBϵ proteins. In HD-MyZ cells, IKK/NF-κB activity is very weak.

IκB protein expression and IKK and NF-κB activation in different HRS cell lines

. | Constitutive NF-κB . | IκBα . | IκBϵ . | Constitutive IKK . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDLM-2 | +++ | wt | wt | ++ |

| L540 | +++ | wt | wt | ++ |

| L428 | +++ | mt | mt | ++ |

| KMH-2 | +++ | mt | wt | ++ |

| L1236 | +++ | wt | wt | ++ |

| HD-MyZ | + | wt | wt | (+) |

. | Constitutive NF-κB . | IκBα . | IκBϵ . | Constitutive IKK . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDLM-2 | +++ | wt | wt | ++ |

| L540 | +++ | wt | wt | ++ |

| L428 | +++ | mt | mt | ++ |

| KMH-2 | +++ | mt | wt | ++ |

| L1236 | +++ | wt | wt | ++ |

| HD-MyZ | + | wt | wt | (+) |

The presence of wild-type (wt) or mutated (mt) IκB proteins as well as constitutive IKK or NF-κB activity is shown. (+) indicates very weak; +, weak; ++, strong; +++, very strong

We investigated the response of representative HRS cell lines toward 2, 5, and 10 μM arsenite (Figure 4). A dose-dependent induction of apoptosis was detectable in the cell lines HDLM-2 and L540 (Figure 4A). Only weak induction of apoptosis was observed in the cell line KMH-2 (15%), whereas L428 and HD-MyZ cells were resistant to arsenite-induced apoptosis. In contrast to the decrease of the constitutive NF-κB activity in the arsenite-sensitive cell lines HDLM-2 and L540, no alteration of the constitutive NF-κB activity was detectable in the cell lines L428 and KMH-2 (Figure 4B). Taken together, only cell lines with wild-type IκB proteins exhibit arsenite-induced apoptosis, and the down-regulation of constitutive NF-κB activity correlates with the induction of apoptosis.

Induction of apoptosis by NaAsO2 correlates with the inhibition of NF-κB.(A) The indicated cell lines were incubated for 24 hours with PBS (□)or 2(▦), 5 (▨), and 10 (▪) μM NaAsO2. The percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by FACS analysis of annexin V+ cells. Error bars denote SDs. (B) The cell lines HDLM-2, L428, and KMH-2 were treated for 24 hours with the indicated concentrations of NaAsO2. Whole cell extracts were analyzed by EMSA for NF-κB DNA binding activity. Free DNA probe is not shown; n.s. indicates nonspecific.

Induction of apoptosis by NaAsO2 correlates with the inhibition of NF-κB.(A) The indicated cell lines were incubated for 24 hours with PBS (□)or 2(▦), 5 (▨), and 10 (▪) μM NaAsO2. The percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by FACS analysis of annexin V+ cells. Error bars denote SDs. (B) The cell lines HDLM-2, L428, and KMH-2 were treated for 24 hours with the indicated concentrations of NaAsO2. Whole cell extracts were analyzed by EMSA for NF-κB DNA binding activity. Free DNA probe is not shown; n.s. indicates nonspecific.

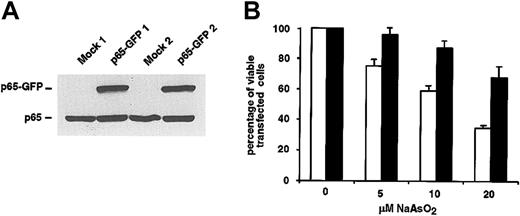

Direct evidence for the involvement of the NF-κB system in arsenic-induced apoptosis

To show a causal relationship between inhibition of NF-κB and arsenic-induced apoptosis, we decided to directly manipulate the NF-κB system by transient transfection of L540Cy cells with an NF-κB–p65-GFP expression plasmid. Overexpression of NF-κB–p65 should maintain an elevated NF-κB–p65 activity despite treatment of the cells with arsenic and therefore rescue the cells from arsenic-induced apoptosis. Indeed, we observed a protection of p65-GFP–transfected L540Cy cells from arsenic-induced apoptosis. After treatment with 5, 10, or even 20 μM arsenite, an increase of the percentage of viable, transfected cells of at least 25% to 30% was detectable in p65-GFP– compared with mock-transfected cells (Figure 5B). The p65-GFP–mediated activation of NF-κB was controlled by luciferase and EMSA analysis (data not shown). Induction of NF-κB activity was reduced by cotransfection with IκBα, indicating intact regulation of the fusion protein. The IκBα-mediated inhibition of the ectopically expressed NF-κB-p65 construct also explains why arsenic-induced apoptosis can be only partially inhibited (Figure 5B).

Overexpression of NF-κB–p65 protects L540Cy cells from arsenite-induced apoptosis.(A) L540Cy cells were transfected with a p65-GFP expression plasmid or with mock and pEGFP-N3 plasmids. Twenty-four hours after transfection, whole cell extracts were analyzed by Western blotting for the expression of p65-GFP and endogenous p65 using a p65-specific antibody. Western blot analysis of 2 independent experiments is shown. (B) Overexpression of NF-κB–p65 protects L540Cy cells from arsenite-induced apoptosis. L540Cy cells were transfected with a p65-GFP expression plasmid (p65-GFP; black bars) or with mock expression plasmid along with pEGFP-N3 (GFP; white bars). Twenty-four hours after transfection, p65-GFP expression was analyzed as described as for panel A and cells were incubated for 16 hours with the indicated concentrations of NaAsO2. Thereafter, PI-stained cells were analyzed by FACS analysis. The decrease of viable GFP+, PI-cells is shown as percentage of viable transfected cells. The combined results of 4 independent experiments are shown; p65-GFP expression for 2 independent experiments is shown in panel A. Error bars denote SDs.

Overexpression of NF-κB–p65 protects L540Cy cells from arsenite-induced apoptosis.(A) L540Cy cells were transfected with a p65-GFP expression plasmid or with mock and pEGFP-N3 plasmids. Twenty-four hours after transfection, whole cell extracts were analyzed by Western blotting for the expression of p65-GFP and endogenous p65 using a p65-specific antibody. Western blot analysis of 2 independent experiments is shown. (B) Overexpression of NF-κB–p65 protects L540Cy cells from arsenite-induced apoptosis. L540Cy cells were transfected with a p65-GFP expression plasmid (p65-GFP; black bars) or with mock expression plasmid along with pEGFP-N3 (GFP; white bars). Twenty-four hours after transfection, p65-GFP expression was analyzed as described as for panel A and cells were incubated for 16 hours with the indicated concentrations of NaAsO2. Thereafter, PI-stained cells were analyzed by FACS analysis. The decrease of viable GFP+, PI-cells is shown as percentage of viable transfected cells. The combined results of 4 independent experiments are shown; p65-GFP expression for 2 independent experiments is shown in panel A. Error bars denote SDs.

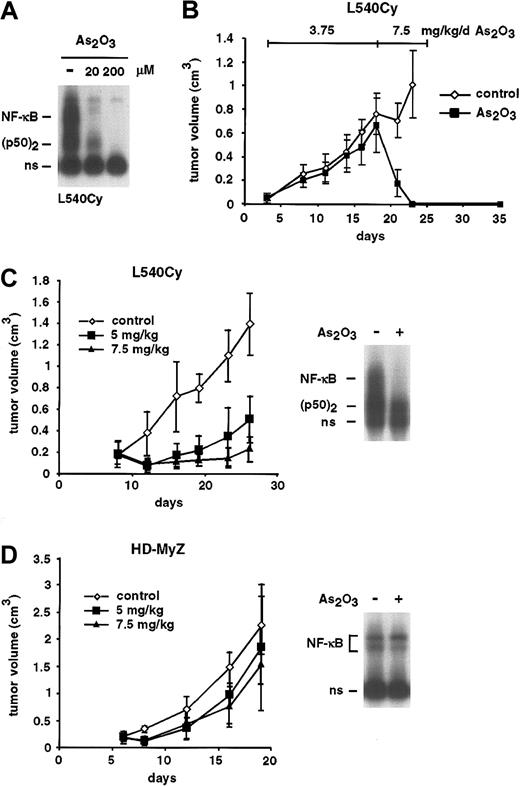

Remission of xenotransplanted Hodgkin tumors in NOD/SCID mice after treatment with arsenic trioxide

Arsenic trioxide (As2O3), in contrast to arsenite, is used in clinical studies. In vitro, both substances behaved similarly regarding the inhibition of NF-κB and induction of apoptosis, even though As2O3 showed stronger biologic effects than NaAsO2 (Figure 6A and data not shown). We investigated the in vivo activity of As2O3 on xenotransplanted Hodgkin tumor cells (Figure 6B-D). In a first experiment, NOD/SCID mice underwent transplantation subcutaneously with the HRS cell line L540Cy. Mice with palpable tumors were treated on days 3 to 17 with 3.75 mg/kg As2O3 intravenously. Only a slight, nonsignificant growth retardation was observed. We therefore decided to continue the treatment with 7.5 mg/kg intravenously daily. Surprisingly, 2 days of treatment with 7.5 mg/kg As2O3 were sufficient to induce a complete remission of the Hodgkin tumors. The treatment was continued for another 6 days (days 20 to 25). Animals of the As2O3-treated group remained in complete remission for 10 days; thereafter, tumor regrowth was observed (not shown). To validate these data, a second experiment with the arsenic-sensitive cell line L540Cy (Figure 6C) as well as with the resistant cell line HD-MyZ (Figure 6D) was performed. Beginning on day 8, mice of both groups were left untreated or treated with 5 or 7.5 mg/kg/d As2O3 intravenously. Again, a dose-dependent strong response, although no complete remission, was observed for the L540Cy tumors. In contrast, HD-MyZ cells were, as shown in vitro, also in vivo clearly less responsive to the application of As2O3. Importantly, EMSA analysis of explanted tumor cells after in vivo application of 7.5 mg/kg As2O3 revealed strong inhibition of constitutive NF-κB activity in L540Cy (Figure 6C) but not in HD-MyZ cells (Figure 6D). In the first experiment, 1 mouse died at day 21; in the second experiment, 2 mice of the 7.5 mg/kg/d–treated group died after 3 weeks of treatment. All other animals showed no relevant signs of toxicity; the body weight decreased in arsenic-treated mice between 3% to 7%.

Remission of L540Cy Hodgkin tumors in a NOD/SCID mouse model after treatment with As2O3. (A) L540Cy cells were treated for 8 hours with the indicated concentrations of As2O3. Whole cell lysates were analyzed for NF-κB DNA binding activity by EMSA. Free DNA probe is not shown; ns indicates nonspecific. (B) L540Cy tumor cells were xenotransplanted in NOD/SCID mice. Mice with palpable tumors were treated for 15 days with PBS (⋄, control; n =6) or 3.75 mg/kg As2O3(▪, n =6) intravenously daily and thereafter for another 8 days with 7.5 mg/kg/d. The tumor volume is indicated. (C-D) Palpable L540Cy (C) or HD-MyZ (D) tumors in NOD/SCID mice were treated with either PBS (⋄, n =6) or 5 (▪, n =6) and 7.5 (▴, n =6) mg/kg/d As2O3intravenously, beginning on day 8 after transplantation. Right panels: modulation of NF-κB activity in L540Cy and HD-MyZ tumor cells in vivo. Animals of the control group were treated on day 24 (L540Cy) or day 18 (HD-MyZ) with PBS alone or with 7.5 mg/kg As2O3intravenously. Tumors were explanted 6 hours after As2O3application. Whole cell extracts of the tumor material were analyzed by EMSA for NF-κB DNA binding activity. Free DNA probe is not shown; ns indicates nonspecific.

Remission of L540Cy Hodgkin tumors in a NOD/SCID mouse model after treatment with As2O3. (A) L540Cy cells were treated for 8 hours with the indicated concentrations of As2O3. Whole cell lysates were analyzed for NF-κB DNA binding activity by EMSA. Free DNA probe is not shown; ns indicates nonspecific. (B) L540Cy tumor cells were xenotransplanted in NOD/SCID mice. Mice with palpable tumors were treated for 15 days with PBS (⋄, control; n =6) or 3.75 mg/kg As2O3(▪, n =6) intravenously daily and thereafter for another 8 days with 7.5 mg/kg/d. The tumor volume is indicated. (C-D) Palpable L540Cy (C) or HD-MyZ (D) tumors in NOD/SCID mice were treated with either PBS (⋄, n =6) or 5 (▪, n =6) and 7.5 (▴, n =6) mg/kg/d As2O3intravenously, beginning on day 8 after transplantation. Right panels: modulation of NF-κB activity in L540Cy and HD-MyZ tumor cells in vivo. Animals of the control group were treated on day 24 (L540Cy) or day 18 (HD-MyZ) with PBS alone or with 7.5 mg/kg As2O3intravenously. Tumors were explanted 6 hours after As2O3application. Whole cell extracts of the tumor material were analyzed by EMSA for NF-κB DNA binding activity. Free DNA probe is not shown; ns indicates nonspecific.

Discussion

Important functions of the constitutive NF-κB activity in diverse tumor cells are to maintain proliferation and to protect cells from apoptosis. As a major cause for this NF-κB activity, a permanent activity of the IKK complex has been identified.23,28 Constitutive IKK/NF-κB activity in tumor cells promotes not only proliferation and survival but also mediates drug resistance.35 Therefore, the use of pharmacologic substances that inhibit constitutive IKK/NF-κB activity could be an important strategy for cancer therapy.

Arsenite is known to block the TNF-α–induced transient activation of NF-κB through the inhibition of the IKK complex.20 Our data show that even constitutive IKK/NF-κB activity is inhibited by arsenic (Figures 1 and 4). We observed an increased or at least unaltered protein expression level of IκBα, whereas simultaneously the IκBα mRNA level decreased (Figure 1). Because IκBα itself is transcriptionally regulated by NF-κB,36 the mRNA decrease indicates the down-regulation of the NF-κB activity. Thus, the IκBα protein is stabilized posttranslationally, most likely due to the inhibition of the IKK complex at low and high concentrations of arsenic (Figure 1). Ectopic expression of the nondegradable super-repressor IκBα▵N in HRS cells to levels comparable to endogenous IκBα in other cell types inhibits the constitutive NF-κB activity.31,32 The increased amount and stability of IκBα protein in HRS cells after treatment with arsenic should therefore be sufficient for the inhibition of the constitutive NF-κB activity.

Inhibition of NF-κB sensitizes HRS cell lines to apoptotic stimuli or even directly induces apoptosis.25,31 Consistent with these results, we observed arsenic-induced apoptosis in several HRS cell lines in vitro (Figures 2, 4, and 5). Apoptosis was not only induced at high concentrations of arsenite but also at concentrations that are tolerated by patients.30 No modulation of the NF-κB activity was detectable in 3 HRS cell lines resistant to arsenite-induced apoptosis (Figure 4). In 2 of them, L428 and KMH-2, IκB proteins are functionally inactive. Thus, the arsenite-induced down-regulation of NF-κB, which requires intact IκB proteins, is inhibited. Compared with the other cell lines investigated, only very weak constitutive IKK/NF-κB activity was detectable in HD-MyZ cells (Table 1). These data indicated a correlation between arsenic-mediated apoptosis and inhibition of IKK/NF-κB activity. To directly examine a causal relationship, L540Cy cells were transfected with NF-κB–p65 expression constructs, resulting in rescue from arsenic-induced apoptosis (Figure 5). We therefore conclude that inhibition of the IKK/NF-κB activity indeed contributes to arsenic-mediated induction of apoptosis.

Treatment of HRS cell lines with arsenite down-regulated several known NF-κB target genes, among these IκBα, IL-13, CCR7, and the antiapoptotic proteins TRAF1 and c-IAP2. Genes such as TRAFs, c-IAPs, IL-13, and CCR7 are overexpressed in HRS cells and are supposed to have an important function with regard to the survival and the dissemination of HRS cells.31,32,34,37 Thus, the combined down-regulation of these genes might explain the strong in vivo antitumor activity of As2O3 on xenotransplanted L540Cy Hodgkin tumor cells. Treatment of NOD/SCID mice with 5 or 7.5 mg/kg/d As2O3 down-regulated NF-κB DNA binding activity and induced a strong reduction of L540Cy tumors (Figure 6). The observation of complete remissions only after treatment of large tumors (Figure 6B) indicates that in these tumors the cells are probably less resistant to induction of apoptosis due to stress factors such as hypoxia. Although the amount of As2O3 applied in the NOD/SCID mouse model is lethal in humans, these data validate our in vitro findings. The resistance of HD-MyZ tumors to As2O3 in vivo and the unchanged NF-κB activity again confirm that inhibition of NF-κB contributes to arsenic-induced apoptosis.

A variety of cell types has been shown to be sensitive to arsenic-induced apoptosis in vitro and in vivo, including APL cells, HTLV-1–infected cells, Bcr-Abl+ CML cells, or prostate carcinoma cells.9,14,17,38,39 For most of these cell types, NF-κB is known to be an essential factor for malignant transformation or survival.40-42 Furthermore, the arsenic-induced down-regulation of NF-κB activity could not only be observed in HRS cell lines. As2O3 specifically inhibits the Tax-induced activation of NF-κB in HTLV-1–transformed cells, and the combination of NF-κB– repressing agents together with As2O3 synergistically induces apoptosis.14,43,44 These data suggest that inhibition of NF-κB contributes to arsenic-induced apoptosis also in these cell types.

What are the mechanisms linking arsenic-mediated NF-κB inhibition and induction of apoptosis? NF-κB–dependent protection from apoptosis involves a number of NF-κB target genes. IAP proteins directly block caspase activity, the Bcl-2 family members Bfl-1/A1 and Bcl-xL prevent the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria, and TRAF proteins may regulate caspase activity and are involved in a regulatory loop, activating NF-κB itself.33,45-47 The combined action of IAPs and TRAFs inhibits activation of caspase-8, the first caspase activated by death receptor signaling.33 In HRS cell lines, arsenite-induced apoptosis involves activation of caspase-8 (Figure 2). The down-regulation of NF-κB–dependent antiapoptotic genes (Figure 3), which can thus no longer function to inhibit caspase-8, therefore appears to be an important regulatory step of arsenite-induced apoptosis in HRS cells.

Taken together, our data indicate that inhibition of NF-κB contributes to the cytotoxic action of arsenic. Although a number of the experiments were performed with concentrations of arsenic that are higher than those achievable in patients (0.5 to 5 μM), most of the data were validated also for low concentrations of arsenic. Increased NF-κB activity has been recognized as an important mechanism leading to drug resistance in tumor cells,48 and inhibition of NF-κB overcomes drug resistance in vitro and in vivo.35 Pharmacologic inhibition of signaling pathways leading to IKK/NF-κB activity might therefore be a powerful treatment option for malignancies with constitutive NF-κB activity, including Hodgkin lymphoma. Thus, inhibition of NF-κB by arsenic might explain its broad therapeutic potential in the treatment of cancer. In addition, arsenic should be evaluated not only as a single agent but also as an adjuvant therapeutic agent in cancer therapy.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, April 3, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1154.

Supported in part by a grant from the Berliner Krebsgesellschaft and a grant from the National Genome Research Network (NGFN).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Franziska Hummel for excellent technical assistance, Thorsten Stühmer for critical reading of the manuscript, and the Experimental Pharmacology & Oncology (I. Fichtner and C. Nowak), Berlin, for performing the animal experiments.

![Figure 1. Inhibition of NF-κB and IKK activity by NaAsO2(A) HDLM-2 and L1236 cells were treated for 8 hours and L540 cells for 48 hours with the indicated concentrations of NaAsO2. Whole cell extracts were analyzed by EMSA for NF-κB DNA binding activity. Free DNA probe is not shown; n.s. indicates nonspecific. (B) Expression level of IκBαmRNA and protein in response to NaAsO2. After incubation of HDLM-2 and L1236 cells for 8 hours with the indicated concentrations of NaAsO2, whole cell extracts were analyzed for IκBαprotein expression by Western blot analysis (WB, upper 2 blots). Total mRNA was prepared after 8 hours and analyzed for expression of IκBαand GAPDH by Northern blotting (NB, lower 4 blots). (C) Arsenite-mediated IKK inhibition. HDLM-2 cells were treated for 8 hours with PBS or 50 μM NaAsO2, or for 48 hours with 1 to 5 μM NaAsO2, as indicated. IKK activity was determined by an in vitro kinase assay (KA). IKKαwas immunoprecipitated using a monoclonal antibody against IKKαand protein A–Sepharose. The precipitates were incubated with IκBαand [γ-32P]ATP at 37°C and subsequently analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. As control, IKKαexpression was analyzed by Western blotting.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/102/3/10.1182_blood-2002-04-1154/6/m_h81534700001.jpeg?Expires=1769130550&Signature=jgBBScUAykpUpbiyg~bhXvODkjOx20lk2Lc168ujljUk19R0gWtOPsGeZXVnFuViSKMyMFaM1q78dhHV5h6-~F4itcCbug-TdcFSJ2dfEMrtmDMaXowhZIicShsg90bQLf4fMnlU1oKkBUvAd13iC-ymzcv1DS6zK32A1Wr17ebhCuf170Rc~~dfk7Iy-60TBjHUbE9E6uX~hclO-SgcvFvQH4hKm4kisZgBYqjnXxuATOMM6ktt6YyLQeOpRi~7k1k-uIE49FmNinqp3I58bpH7lc3lSRusqUTWfaz0XXpcVEA~jyMitMsgVSD5PbxxsVnqwr-0LW6OzBOv8nXXlQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal