Abstract

Mutations in the human telomerase RNA (TERC) occur in autosomal dominant dyskeratosis congenita (DKC). Because of the possibility that TERC mutations might underlie seemingly acquired forms of bone marrow failure, we examined blood samples from a large number of patients with aplastic anemia (AA), paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), and myelodysplasia (MDS). Only 3 of 210 cases showed heterozygous TERC mutations: both nucleotide 305 (n305) (G>A) and n322 (G>A) were within the conserved region (CR) 4–CR5 domain; n450 (G>A) was localized to the boxH/ACA domain. However, only one patient (with a mutation at n305 [G>A]) had clinical characteristics suggesting DKC; her blood cells contained short telomeres and her sister also suffered from bone marrow failure. Another 21 patients with short telomeres did not show TERC mutations. Our results suggest that cryptic DKC, at least secondary to mutations in the TERC gene, is an improbable diagnosis in patients with otherwise typical AA, PNH, and MDS.

Introduction

Aplastic anemia (AA), pancytopenia, and a hypocellular bone marrow may be acquired or constitutional.1 Constitutional types of marrow failure, Fanconi anemia and dyskeratosis congenita (DKC), typically present in the first or second decade of life, frequently with associated physical anomalies.2,3 Detailed analysis of large families, collected in a DKC registry, allowed identification of several putatively etiologic genes in DKC. Mutations in the DKC1 gene occur in the X-linked form of the disease4,5 ; DKC1 encodes dyskerin, which binds to the human telomerase RNA (TERC).6 Subsequently, mutations in TERC were identified in autosomal dominant DKC.7 The involvement of these genes has implicated the telomerase complex in the pathophysiology of DKC.8-10

By analogy with Fanconi anemia, a diagnosis of DKC has been sought in patients with seemingly acquired AA. In a small study by Vulliamy et al,11 abnormalities in TERC were identified in more than 10% of patients with AA, apparently acquired late in life. We identified 2 families in which the probands presented with “acquired” AA but for whom stem cells could not be mobilized from matched sibling donors.12 In each kindred, a new mutation in TERC and short telomeres were observed in multiple family members, associated with very mild blood count abnormalities, except in the proband, and no physical anomalies.12 Because of the possibility that TERC mutations might underlie other cases of bone marrow failure, we undertook to examine a large number of blood samples from patients with AA, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), and myelodysplasia (MDS).

Study design

Patients

Blood samples, previously collected and frozen, had been obtained from a total of 210 patients with bone marrow failure syndromes (150 AA, 55 MDS, and 13 PNH). Living patients provided informed consent for genetic testing according to protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. For controls, we analyzed a panel of genomic DNA from 194 healthy donors, comprising 123 white, 23 Hispanic, 24 black, and 24 Asian individuals (http://snp500cancer.nci.nih.gov. Accessed May 13, 2003).

Telomere fluorescence in situ hybridization and flow cytometry

Mutation analysis of the TERC gene

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers for amplification of around chromosome 3q26.3, including promoter and transcription region of TERC, were designed. We defined the first nucleotide of TERC transcription region as nucleotide 1 (n1). TERCF1-1; (n1660) GAGCTCATATAGAGCAGAACAAG, and TERCR4; GGTGACGGATGCGCACGAT (n502), and TERCF4; (n150) TCATGGCCGGAAATGGAACT, and TERCR7-1; and TGCACTTGTCTGTAGTTCAAGGAG (n1939) were amplified to detect deletions of the TERC gene. PCR amplification of the genomic DNA was performed by Advantage-GC2PCR kit (BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). The PCR conditions were as follows: preheating at 94°C for 3 minutes; followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds, 58°C for 50 seconds, and 68°C for 3 minutes; and a final extension at 68°C for 5 minutes.

We designed 2 pair primers for sequencing. Primer sequences are as follows: TERCF4 and TERCseqR1; GTTTGCTCTAGAATGAACGGTGG, TERCseqF2; GTCTAACCCTAACTGAGAAGGGC, and TERCR4. Reactions for direct sequencing of the PCR products were performed with BigDye Terminator ver3.1 (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Fremont, CA).

Results and discussion

TERC abnormalities in unselected bone marrow failure patients

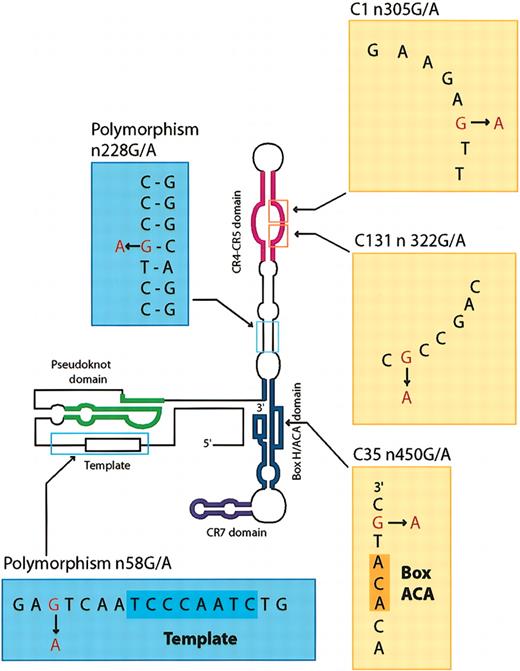

We sought large deletions in TERC by PCR, but none were found (data not shown) (however, our screening method would not detect novel deletions of TERC whose borders fell outside the limits of our primers). Direct sequencing showed only 3 heterozygous TERC mutations among 210 patient samples examined, for an approximate frequency in the range of 1.5% (Table 1). Both n305 (G>A) and n322 (G>A) were within the CR4-CR5 domain; n450 (G>A) was located in the boxH/ACA domain (Table 1; Figure 1). Of 22 patients in whom telomere length was previously determined to be short compared with age-matched controls,15 only 1 showed a TERC mutation: n305 (G>A) (Table 2).

TERC mutations and polymorphisms

. | n21 (C > T)* . | n58 (G > A) . | n228 (G > A) . | n305 (G > A) . | n322 (G > A) . | n450 (G > A) . | n467 (T > C)† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA or AA/PNH (n = 150) and PNH (n = 5) | 0/155 | 1/155 | 1/155 | 1/155 | 0/155 | 1/155 | 1/155 |

| MDS (n = 55) | 0/55 | 2/55 | 0/55 | 0/55 | 1/55 | 0/55 | 0/55 |

| Total | 0/210 | 3/210 | 1/210 | 1/210 | 1/210 | 1/210 | 1/210 |

| Healthy controls‡ | |||||||

| White | 1/123 | 0/123 | 0/123 | 0/123 | 0/123 | 0/123 | 0/123 |

| Hispanic | 0/23 | 0/23 | 0/23 | 0/23 | 0/23 | 0/23 | 0/23 |

| Black | 0/24 | 5/24 | 1/24 | 0/24 | 0/24 | 0/24 | 0/24 |

| Asian | 0/24 | 0/24 | 0/24 | 0/24 | 0/24 | 0/24 | 0/24 |

| Total | 1/194 | 5/194 | 1/194 | 0/194 | 0/194 | 0/194 | 0/194 |

. | n21 (C > T)* . | n58 (G > A) . | n228 (G > A) . | n305 (G > A) . | n322 (G > A) . | n450 (G > A) . | n467 (T > C)† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA or AA/PNH (n = 150) and PNH (n = 5) | 0/155 | 1/155 | 1/155 | 1/155 | 0/155 | 1/155 | 1/155 |

| MDS (n = 55) | 0/55 | 2/55 | 0/55 | 0/55 | 1/55 | 0/55 | 0/55 |

| Total | 0/210 | 3/210 | 1/210 | 1/210 | 1/210 | 1/210 | 1/210 |

| Healthy controls‡ | |||||||

| White | 1/123 | 0/123 | 0/123 | 0/123 | 0/123 | 0/123 | 0/123 |

| Hispanic | 0/23 | 0/23 | 0/23 | 0/23 | 0/23 | 0/23 | 0/23 |

| Black | 0/24 | 5/24 | 1/24 | 0/24 | 0/24 | 0/24 | 0/24 |

| Asian | 0/24 | 0/24 | 0/24 | 0/24 | 0/24 | 0/24 | 0/24 |

| Total | 1/194 | 5/194 | 1/194 | 0/194 | 0/194 | 0/194 | 0/194 |

21 base pair upstream from 5′ transcription region of TERC

16 bp downstream from 3′ transcription region of TERC

Healthy controls are SNP500

Mutations and polymorphisms of TERC gene. The schematic of the TERC gene showing the positions of mutations and polymorphisms identified in patients and healthy controls.

Mutations and polymorphisms of TERC gene. The schematic of the TERC gene showing the positions of mutations and polymorphisms identified in patients and healthy controls.

Summary of patients' background with TERC mutation

Case no. . | Mutation, sex/age/race . | Diagnosis . | Family history . | Chromosome abnormality . | Telomere length in leukocytes, kb . | Treatment response . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | n305 (G > A), F/15 y/H | mAA | Affected twin sister | None | 4.6 | Response to danazol |

| C35 | n450 (G > A), F/31 y/W | sAA | Negative | None | 11 | Response to ATG + CSA |

| C131 | n322 (G > A), M/77 y/W | MDS RA | Negative | del(5)(q15;q13) | Not done | No response to Epo or CSA |

Case no. . | Mutation, sex/age/race . | Diagnosis . | Family history . | Chromosome abnormality . | Telomere length in leukocytes, kb . | Treatment response . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | n305 (G > A), F/15 y/H | mAA | Affected twin sister | None | 4.6 | Response to danazol |

| C35 | n450 (G > A), F/31 y/W | sAA | Negative | None | 11 | Response to ATG + CSA |

| C131 | n322 (G > A), M/77 y/W | MDS RA | Negative | del(5)(q15;q13) | Not done | No response to Epo or CSA |

F indicates female; H, Hispanic; W, white; M, Male; mAA, moderate aplastic anemia; ATG, antithymocyte globulin; CSA, cyclosporin A; sAA, severe aplastic anemia; RA, refractory anemia; Epo, erythropoietin

All vertebrate telomerase RNAs share 4 highly conserved structural regions: a pseudoknot domain, a CR4-CR5 domain, a boxH/ACA domain, and a CR7 domain.6,16 The pseudoknot and CR4-CR5 domains are known to be necessary for telomerase activity.6,17 A sister of the patient with the n305 (G>A) mutation also suffered from bone marrow failure; we had previously measured an extremely short telomere length for the patient (Table 2). Mouse mutations in the homologous P6 region of CR4-CR5 domain of murine telomere RNA, corresponding to the J6/5 unpaired region of human telomere RNA,16 abolish the ability to reconstitute an active telomerase complex.18 Therefore, telomere shortening and pancytopenia in this patient were probably secondary to this single nucleotide substitution.

Because telomeres are believed to play an important role in the maintenance of chromosome integrity, genetic instability has been attributed to age-related loss of telomeric DNA in hematopoietic stem cells6 in the pathogenesis of de novo MDS.19 However, we found only a single MDS patient with a TERC mutation (n322 [G>A]), at the J6/5 unpaired region of the CR4/CR5 domain (Table 1; Figure 1). No telomere length data were available for this archived case. While it remains possible that telomeric shortening was related to the hematologic disease, TERC mutations in general were certainly not prevalent in the MDS patients that we studied. For the n450 (G>A) substitution, a pathogenic role is uncertain in the absence of either telomere data or a suggestive family history (Table 2); furthermore, this patient had a more typical course for acquired AA, with a good and sustained response to immunosuppressive therapy (Table 2). Additionally, we found the n467 (T>C) substitution at the 3′ downstream region in a single AA patient (Table 1); the biologic significance of this substitution is unclear.

The absence of these particular mutations, even in the large number of normal controls that we examined (n = 388 chromosomes), strongly suggests that these are rare mutations and not common single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs).20 However, testing of the ability of these TERC mutations to diminish telomerase activity in transfected cells in vitro is required to establish their pathogenic role.

Polymorphisms in TERC

We analyzed 194 healthy controls of different self-described ethnicities to determine if the variants represented polymorphisms.20 Most important was the n58 (G>A) substitution, which was observed in 5 blacks, and the n228 (G>A), found in a single black (Table 1). We also found the n21 (C>T) substitution at the 5′ upstream region. Two black MDS patients and a single black AA patient showed the n58 (G>A) polymorphism, and a single AA patient showed the n228 (G>A) polymorphism21 (Table 1). For the n228 (G>A) polymorphism, this base pair is disrupted within a hypervariable paired region (Figure 1) and would not be predicted to be important in the required secondary structure of TERC.

Our results and data on a small number of patients reported in correspondence22,23 stand in particular contrast to those reported by Vulliamy et al11 ; the sequence substitution that they identified in their cases of idiopathic and presumed constitutional AA—n58 (G>A)—is unlikely to represent a true mutation, being present in a large proportion of healthy black individuals. When these cases are subtracted, the English series contains only 2 patients with a clinical diagnosis of constitutional AA with TERC mutations, at n72 (C>G) and n110-113 (deletion GACT).11

Finally, we and others have reported short telomeres in a substantial proportion of patients with AA.15,24,25 While many such examples were studied in the current study, TERC mutations were not found; of course, other components of the telomerase complex might be affected and thus explain the telomere shortening. Mutations in appropriate crucial regions of these genes could result in a phenotype similar to those associated with TERC abnormalities. Therefore, we cannot rigorously exclude cryptic DKC owing to mutations in telomerase complex components other than TERC in marrow failure syndromes.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, April 3, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0335.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal