The BCL10 gene, originally identified through its recurrent involvement in t(1;14)(p22;q32) of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, encodes a cytosolic protein composed of 233 amino acid residues with proapoptotic and proinflammatory activities.1 B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia/lymphoma 10 (BCL10) is widely expressed in the cytoplasm of normal lymphoid tissues, with the expression level depending on the developmental stage of lymphocytes.2 Many B-cell lymphomas also express BCL10, including MALT lymphoma.2 In contrast to normal B cells that express BCL10 in the cytoplasm, MALT lymphoma cells with t(1;14)(p22;q32) or t(11;18)(q21;q21) express the protein predominantly in the nucleus.2-5 Since there are no available data on BCL10 expression in natural killer (NK) cells, we examined BCL10 expression in normal NK cells and nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma (NL) in this study.

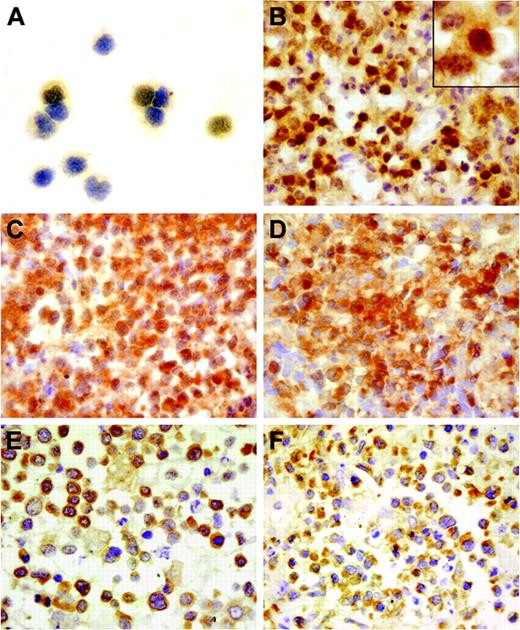

BCL10 immunostaining was performed on the cytospin preparations of CD3–/(CD16+CD56)+ normal NK cells isolated from the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of 2 healthy volunteers by cell sorting and paraffin sections of 40 NL tumor specimens using the monoclonal antibody clone 151 (1:50; Zymed, South San Francisco, CA).2 Because the NK cells were isolated from PBMCs by cell sorting, anti-(CD16+CD56) monoclonal antibodies were still bound to the antigens on the cell surface. Blocking them by a goat antimouse antibody (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) was performed to reduce the nonspecific binding. Immunostaining results showed BCL10 expression in NK cells and all 40 NL cases. BCL10 expression was detected only in the cytoplasm of NK cells (Figure 1A); by comparison, in addition to cytoplasmic expression, 28 (70%) of 40 NL cases showed aberrant nuclear staining of BCL10 in a variable percentage of NL tumor cells (Figure 1B). Paraffin sections of reactive tonsils were stained as controls, and only cytoplasmic staining of BCL10 was present among these tissues.

BCL10 protein expression in normal NK cells and NL and the NF-κB expression in NL. (A) A moderate immunoreactivity was detected only in the cytoplasm of NK cells. (B) The NL tumor cells from case 29 showed strong BCL10 expression in both the nucleus and cytoplasm. (C) Cytoplasmic BCL10 staining and aberrant nuclear staining of BCL10 on the tumor cells in case 28. (D) Nuclear localization of NF-κB was prominent in the same case in addition to the cytoplasmic staining, indicative of NF-κB activation in the tumor cells. (E) Cytoplasmic staining of BCL10 was present in the tumor cells of case 22. (F) Cytoplasmic localization of NF-κB is shown in the same case. Immunoperoxidase staining: original magnifications of panels A-F and inset in panel B are × 400 and × 1000, respectively.

BCL10 protein expression in normal NK cells and NL and the NF-κB expression in NL. (A) A moderate immunoreactivity was detected only in the cytoplasm of NK cells. (B) The NL tumor cells from case 29 showed strong BCL10 expression in both the nucleus and cytoplasm. (C) Cytoplasmic BCL10 staining and aberrant nuclear staining of BCL10 on the tumor cells in case 28. (D) Nuclear localization of NF-κB was prominent in the same case in addition to the cytoplasmic staining, indicative of NF-κB activation in the tumor cells. (E) Cytoplasmic staining of BCL10 was present in the tumor cells of case 22. (F) Cytoplasmic localization of NF-κB is shown in the same case. Immunoperoxidase staining: original magnifications of panels A-F and inset in panel B are × 400 and × 1000, respectively.

It has been previously shown that BCL10 is involved in nuclear factor–κB (NF-κB) activation by in vitro overexpression assay1 and by BCL10 knock-out in mice.6 Because NF-κB transfer from cytoplasm to nucleus is the hallmark of its activation, we investigated NF-κB localization in the same 40 NL cases by immunostaining using polyclonal antibody C-20 (1:2000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) against NF-κB p65 and compared the results with the BCL10 expression pattern in NL (Figure 1C-F). The statistical analysis of the data by the chi-square test in Table 1 showed a strong association between BCL10 nuclear localization and NF-κB activation in NL (P = .001). The positive cases contained more than 10% of the tumor cells with nuclear staining.

Aberrant nuclear localization of BCL10 and NF-κB activation in 40 NL cases

. | NF-κB . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|

. | + . | - . | |

| BCL10 | |||

| + | 23 | 5 | |

| - | 3 | 9 | |

. | NF-κB . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|

. | + . | - . | |

| BCL10 | |||

| + | 23 | 5 | |

| - | 3 | 9 | |

The positive cases contained more than 10% of the tumor cells with nuclear staining. The statistical analysis showed a strong association between aberrant BCL10 nuclear localization and NF-κB activation in NL (P = .001).

In conclusion, our results show that BCL10 is widely expressed among normal and neoplastic NK cells and may exert the same regulatory role in NF-κB signaling in NK cells as in T and B cells. Many NL tumors have the same nuclear staining of BCL10 as the MALT lymphomas, but the chromosomal abnormalities, t(1;14)(p22;q32) and t(11;18)(q21;q21), which are the hallmarks of MALT lymphoma,1-5 are not present in NL.7,8 The unexpected finding of BCL10 nuclear localization and its association with NF-κB activation indicated a novel mechanism leading to aberrant BCL10 nuclear localization during tumorigenesis of NL.

Supported by a grant from the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, PR China (HKU 7348/02M to G.S.).

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal