Abstract

Anaplasma phagocytophilum causes human granulocytic ehrlichiosis, the second most common tick-borne disease in the United States. Mice are natural reservoirs for this bacterium and man is an inadvertent host. A phagocytophilum's tropism for human neutrophils is linked to neutrophil expression of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1), as well as sialylated and α1,3-fucosylated glycans. To determine whether A phagocytophilum uses similar molecular features to infect murine neutrophils, we assessed in vitro bacterial binding to neutrophils from and infection burden in wild-type mice; mice lacking α1,3-fucosyltransferases Fuc-TIV and Fuc-TVII; or mice lacking PSGL-1. Binding to Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- neutrophils and infection of Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- mice were significantly reduced relative to wild-type mice. A phagocytophilum binding to PSGL-1-/- neutrophils was modestly reduced, whereas sialidase treatment significantly decreased binding to both wild-type and PSGL-1-/- neutrophils. A phagocytophilum similarly infected PSGL-1-/- and wild-type mice in vivo. A phagocytophilum induced comparable levels of chemokines from wild-type and PSGL-1-/- neutrophils in vitro, while those induced from Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- neutrophils were appreciably reduced. Therefore, A phagocytophilum infection in mice, as in humans, requires sialylation and α1,3-fucosylation of neutrophils. However, murine infection does not require neutrophil PSGL-1 expression, which has important implications for understanding how A phagocytophilum binds and infects neutrophils.

Introduction

Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) is a tick-transmitted disease first documented in the United States within the past decade.1,2 A bacterium recently renamed Anaplasma phagocytophilum,1-3 which is the focus of this study, and Erhlichia ewingii4 are the etiologic agents of HGE. Clinical manifestations associated with HGE include fever, headache, myalgia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and impaired host defense mechanisms.5,6 If left untreated, severe disease can be fatal due to increased susceptibility to opportunistic infections, particularly for the elderly.7,8 The hallmark of HGE is the colonization of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (neutrophils).1,9

A phagocytophilum is normally maintained in a zoonotic cycle that involves an arthropod vector, Ixodes species, and reservoir hosts such as the white-footed mouse, Peromyscus leucopus.10-12 Human infection is inadvertent and does not play a role in the bacterium's life cycle. Models of A phagocytophilum infection using laboratory mice have increased our understanding of this pathogen. Mice challenged with A phagocytophilum develop an acute infection, similar to that observed for HGE, in which morulae, intracytoplasmic bacterial inclusions, are evident in peripheral neutrophils at 3 to 20 days after challenge.13-16 Interferon γ (IFN-γ) is prominently produced early in murine infection, which has also been described for human disease.17 Moreover, A phagocytophilum inhibits the neutrophil respiratory burst during human18-20 and murine21 infection.

The tropism of A phagocytophilum for human neutrophils is explained, at least in part, by the expression of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1)22 and sialylated and α1,3-fucosylated glycans such as sialyl Lewis x (sLex)23 on neutrophil surfaces. The adhesion molecules P-, E-, and L-selectin use related features to mediate rolling of leukocytes on vascular surfaces during the initial stages of inflammation. All 3 selectins recognize sLex and related α1,3-fucosylated glycans.24-28 Targeted disruption of the genes encoding Fuc-TIV and Fuc-TVII, the α1,3-fucosyltransferases expressed in murine leukocytes, eliminates selectin-dependent leukocyte interactions in vivo.29,30 Disruption of the gene encoding PSGL-1, a homodimeric mucin on leukocytes, virtually inhibits leukocyte rolling on P-selectin and diminishes leukocyte tethering to E-selectin.31,32 Monoclonal antibodies to N-terminal epitopes on human and murine PSGL-1 inhibit leukocyte interactions with P- and L-selectin.33-41 P-selectin binds preferentially to the N-terminus of human PSGL-1 through recognition of tyrosine sulfate residues, adjacent peptide determinants, and a short core-2 O-glycan capped with sLex.26,35,42-45 Murine PSGL-1 may require a related series of modifications to bind to P-selectin.46 Goodman and colleagues23 demonstrated that binding of A phagocytophilum to human myeloid HL-60 cells requires cell surface sialylation and correlates with expression of Fuc-TVII. Furthermore, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to N-terminal epitopes on human PSGL-1 inhibit the ability of A phagocytophilum to bind to and infect human neutrophils or HL-60 cells.22 Expression of both PSGL-1 and Fuc-TVII in heterologous cells rendered them susceptible to binding and infection by A phagocytophilum.22 This suggested that, like P-selectin, A phagocytophilum specifically binds to fucosylated PSGL-1.

Studies in mice allow analysis of A phagocytophilum infection both in vitro and in vivo and provide a model for human disease. We therefore asked whether A phagocytophilum also exploits the properties of selectin ligands to infect murine neutrophils. For this purpose, we used in vitro and in vivo assays to measure A phagocytophilum binding and infection in neutrophils in wild-type mice, PSGL-1-deficient mice,32 and mice deficient in both Fuc-TIV and Fuc-TVII.30 A phagocytophilum binding to murine neutrophils, as to human neutrophils, required expression of α1,3-fucosyltransferases. Remarkably, A phagocytophilum binding to murine neutrophils, unlike that to human neutrophils, did not require expression of PSGL-1.

Materials and methods

Cultivation of A phagocytophilum and maintenance of infection

A phagocytophilum strain NCH-147 was cultivated in HL-60 cells as previously described.18 A phagocytophilum infection was also sustained in vivo by inoculating inbred C3H-scid mice with A phagocytophilum-infected HL-60 cells. Infected blood from C3H-scid mice was used as inocula to initiate infection in test animals as previously reported.17

Murine model of A phagocytophilum infection

The generation of PSGL-1-deficient (PSGL-1-/-) mice was described previously.32 Fuc-TIV/Fuc-TVII-deficient (Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/-) mice30 were a gift from Dr John Lowe and Dr Robert J. Kelly (University of Michigan Medical Center). Littermates were used as controls for PSGL-1-/- mice. C57BL/6J mice were used as controls for Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- mice because the latter were backcrossed at least 10 generations into the C57BL/6J background. Each murine infection time course was performed using groups of three 6- to 8-week-old knockout or control mice. Mice were intraperitoneally injected with 100 μL of anticoagulant-treated (1 mM EDTA [ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid]), A phagocytophilum-infected C3H-scid (severe combined immunodeficiency) mouse blood. Ten percent of the neutrophils in the blood of the donor SCID mice contained morulae. Equivalent numbers of each mouse genotype were also shaminoculated with 100 μL of uninfected C3H-scid mouse blood. The level of bacteremia was monitored by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and light microscopy. The PSGL-1-/- mice and the corresponding controls were monitored on days 3, 7, 15, 21, and 28. The Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- mice and corresponding controls were monitored on days 5, 7, 14, 21, and 28. To ensure reproducibility, each time course experiment for murine infection was performed twice using different sets of mice.

Confirmation of A phagocytophilum infection by PCR and light microscopy

One hundred microliters of peripheral blood from each mouse was collected in anticoagulant-containing tubes followed by incubation in erythrocyte lysis buffer (155 mM NH4Cl; 10 mM KHCO3; 1 mM EDTA). DNA was extracted using the DNA Easy Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). DNA samples were normalized using terminal dilution PCR. Briefly, each template was serially diluted and subjected to PCR using primers murine hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase-forward primer 1 (mHPRT-F1) (5′-TCA CCC AGT CTC CAG CAA TCA TG-3′) and mHPRT-reverse primer 1 (R1) (5′-ACG TGT AAC CAC TCC GCT GAT G-3′), which target the gene for murine HPRT. The dilution at which PCR product could no longer be detected was designated as the “terminal dilution.” DNA samples were normalized according to the ratio of their terminal dilutions. Normalized samples were resubjected to PCR analysis using mHPRT-F1 and mHPRT-R1 and were also assessed for A phagocytophilum infection using primers p44-F1 (5′-TCAAGA CCAAGG GTA TTA GAG ATA G-3′) and p44-R1 (5′-GCC ACT ATG GTT TTT TCT TCG GG-3′), which target members of the A phagocytophilum p44 gene family.48-50 In some cases, primers 16S-F1 (5′-TGT AGG CGG CGG TTC GGT AAG TTA AAG-3′) and 16S-R1 (5′-GCA CTC ATC GTT TAC AGC GTG-3′), which target the A phagocytophilum 16S ribosomal RNA gene, were used. The thermal cycling conditions were as described.18 PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis in 1.5% agarose gels.

The percentage of A phagocytophilum-infected neutrophils was determined at every time point for each mouse. Peripheral blood smears were prepared from anticoagulant-treated blood and stained with Diff-Quick (Baxter Healthcare, Miami, FL). Peripheral blood neutrophils were examined for morulae by counting at least 200 cells under light microscopy. Since deficiencies in Fuc-TIV and Fuc-TVII result in leukocytosis30 ; at least 1000 neutrophils were counted per Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- mouse. The percentage of cells with morulae was expressed as the mean value ± SD of the 3 mice per group.

Assessment of respiratory burst activity in A phagocytophilum-infected murine neutrophils

On days 7 and 28 after infection, 100 μL of blood from A phagocytophilum-infected PSGL-1-/-, Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/-, and control mice (3 per group) was collected in anticoagulant-treated tubes and incubated with 4 mL of erythrocyte lysis buffer at room temperature for 5 minutes. Blood samples from uninfected mice served as positive controls. The erythrocyte-free cell suspensions were processed and examined for NADPH (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate) oxidase activity using the Fc-Oxyburst assay.21

Measurement of murine neutrophil chemokine production

Host cell-free A phagocytophilum were prepared as described.18 The number of host cell-free A phagocytophilum obtained was estimated by the following formula: number of A phagocytophilum = total number of infected cells × average number of morulae in an infected cell (typically 5) × average number of bacteria per morulae (typically 19) × percentage of bacteria recovered as host cell free (typically 50%).51,52

Murine neutrophils were isolated from 750 μL blood from Fuc-TIV-/-/ Fuc-TVII-/-, PSGL-1-/-, or control mice by centrifugation through an equal volume of Polymorphprep (Axis-Shield; Greiner Bio-One, Frickenhausen, Germany) at 470g for 30 minutes. The neutrophils were removed by aspiration, mixed with equal volumes of 0.45% NaCl, centrifugated at 350g for 10 minutes, washed twice with Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS), and enumerated using a hemacytometer. Suspensions of 25 000 neutrophils in 250 μL of HBSS/10% fetal calf serum (FCS)/2 mg/mL dextrose were added per well of a 24-well plate. Host cell-free A phagocytophilum were added at multiplicities of infection of approximately 4000, 400, and 40 bacteria/cell. As a control for chemokine induction, the cultures were also incubated with 1 μg/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Escherichia coli 0127:B8; Difco, Detroit, MI). Twenty-four hours after infection, macrophage inflammatory protein 2 (MIP-2) and keratinocyte-derived chemokine (KC) levels were measured for A phagocytophilum-infected and uninfected PSGL-1-/- and control mouse neutrophils as described.53

Measurement of binding of mAbs or A phagocytophilum to cells by flow cytometry

Host cell-free A phagocytophilum were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), followed by incubation in 10 μM CellTracker Green (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) in Optimem media (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) for 45 minutes at 37°C. Labeled bacteria were washed twice with PBS to eliminate unincorporated CellTracker Green and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde (PFA).

Murine leukocytes were isolated from heparinized peripheral blood as described.32 After erythrocyte lysis, leukocytes were washed with PBS and pretreated with 20 μg/mL Fc Receptor Blocker (Accurate Chemicals, Westbury, NY) for 20 minutes at room temperature. To distinguish neutrophils, T cells, and B cells, preliminary experiments were performed in which leukocytes were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled antimouse Ly-6G (Gr-1), antimouse CD3, or antimouse CD19 (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA). These staining patterns were used to assign gates to neutrophils, T cells, or B cells by their forward scatter versus side scatter properties. Leukocytes from wild-type or PSGL-1-/- mice were incubated with phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled anti-mouse PSGL-1 mAb 2PH1 or FITC-conjugated mAb 2H5 (BD PharMingen), which binds to sLex and to some sialylated but nonfucosylated glycans.

Transfected Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells coexpressing FTVII, core-2 β1-6-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase, and either human or murine PSGL-1 were prepared as described.46,54 Cells were incubated with murine anti-human PSGL-1 mAb PL1 or rat anti-murine PSGL-1 mAb 4RA1055 (a gift of Dr Dietmar Vestweber, University of Muenster, Germany). Bound antibodies were detected by FITC-labeled goat antimouse IgG or FITC-labeled goat antirat IgG (both from Caltag, Burlingame, CA). Cell-surface expression of sLex epitopes was measured by incubation with rat anti-sLex mAb HECA-452 (American Type Culture Collection [ATCC], Manassas, VA) followed by incubation with FITC-labeled goat antirat IgM (BD PharMingen).

For assessment of bacteria binding, 106 leukocytes or CHO cells in 1 mL of 0.5% human serum albumin in HBSS with Ca++ and Mg++ were incubated with CellTracker Green-labeled, PFA-fixed A phagocytophilum (bacteria to leukocyte ratio ∼ 15:1) at room temperature for 30 minutes. In some experiments, leukocytes or CHO cells were incubated with a mixture of sialidases (0.6 U/mL sialidase from Arthrobactor ureafaciens and 5 μg/mL sialidase from Vibrio cholerae in HBSS buffer with 1% human serum albumin) at 37°C for 1 hour before the addition of labeled bacteria. Following incubation, 1 mL 0.5% human serum albumin in HBSS with Ca++ and Mg++ was added and unbound bacteria were removed by centrifugation at 300g. The cells were fixed with 1% PFA.

Flow cytometric detection of bound molecules or bacteria was performed using a FACScan flow cytometer using CellQuest software (BD PharMingen).

Statistical analysis

A comparison of the percentage of neutrophils with morulae and chemokine concentrations were performed using the Student t test. Statistical signifi-cance was set at P < .06.

Results

Binding of A phagocytophilum to Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- murine neutrophils is severely compromised

A phagocytophilum binding to human myeloid cells in vitro is correlated with the expression of the α1,3-fucosyltransferase, Fuc-TVII.22,23 We therefore investigated the importance of α1,3-fucosyltransferase to the binding of murine neutrophils. Leukocytes from wild-type mice or mice deficient in Fuc-TIV and Fuc-TVII, the 2 α1,3-fucosyltransferases expressed in leukocytes,25 were incubated with CellTracker Green-labeled, PFA-fixed A phagocytophilum and assessed by flow cytometry. Fixation of A phagocytophilum enabled specific assessment of bacteria-host cell interaction, as it eliminated the potential variable of active bacterial invasion. A phagocytophilum exhibited strong binding to wild-type neutrophils, as 94.3% ± 1.2% of the neutrophils were bound (Figure 1A). In striking contrast, binding to Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- neutrophils was appreciably reduced as only 11.7% ± 2.1% neutrophils were bound (Figure 1B). The mean fluorescent intensities (MFI) for binding to control and Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- neutrophils were 50.7 ± 4.5 and 8.0 ± 1.0, respectively. A phagocytophilum bound weakly to both Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- and wild-type lymphocytes. Thus, α1,3-fucosylation is critical for A phagocytophilum to optimally bind murine neutrophils.

Binding of A phagocytophilum to Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- murine neutrophils is severely reduced. CellTracker Green-labeled, PFA-fixed A phagocytophilum were incubated with leukocytes from (A) wild-type and (B) Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- mice. Bacterial binding was directly correlated to CellTracker Green fluorescence using flow cytometry. In each panel, a thick line indicates neutrophils; and a thin line, lymphocytes. Assays were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as the mean percentage (± SD) of leukocytes bound by bacteria. Representative data from at least 2 studies are shown.

Binding of A phagocytophilum to Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- murine neutrophils is severely reduced. CellTracker Green-labeled, PFA-fixed A phagocytophilum were incubated with leukocytes from (A) wild-type and (B) Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- mice. Bacterial binding was directly correlated to CellTracker Green fluorescence using flow cytometry. In each panel, a thick line indicates neutrophils; and a thin line, lymphocytes. Assays were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as the mean percentage (± SD) of leukocytes bound by bacteria. Representative data from at least 2 studies are shown.

Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- mice are far less susceptible to A phagocytophilum infection than wild-type mice

After observing that a lack of α1,3-fucosyltransferase appreciably limits A phagocytophilum binding to murine neutrophils in vitro, we next assessed whether this compromises the ability of A phagocytophilum to establish infection in vivo. Groups of Fuc-TIV-/-/ Fuc-TVII-/- and wild-type mice were challenged with A phagocytophilum and assessed for infection by examining for the presence of A phagocytophilum DNA in the peripheral blood using PCR by assessing the percentage of peripheral blood neutrophils containing morulae and by determining the impact of A phagocytophilum on neutrophil NADPH oxidase.

In contrast to that observed for control mice, infection of Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- mice was considerably reduced. On days 5 and 7, which typically represent peak bacteremia,13-16 peripheral blood samples for control mice were strongly positive for A phagocytophilum DNA, whereas those of Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- mice yielded much weaker amplicons (Figure 2A). The percentage of peripheral blood neutrophils with morulae was also appreciably lower for Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- mice versus wild-type mice. On day 5 after inoculation, the mean percentage of neutrophils positive for A phagocytophilum infection was 3.8% for control mice (Figure 2B). Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- mice had a mean of 0.1%, representing a 38-fold decrease. By day 7, A phagocytophilum inclusions were detectable in 7.5% of wild-type neutrophils. Infection of Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- mice was reduced 15-fold, as only 0.5% of neutrophils contained morulae. On day 14, peripheral blood infection had resolved considerably as 0.5% of wild-type and only 0.03% of Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- murine neutrophils were colonized. On day 21, the A phagocytophilum burden of wild-type mice remained low at 0.9%. Morulae were not discernible in any of the control mice on day 28 or in any of the Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- mice on days 21 and 28.

A phagocytophilum infection is severely compromised in Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- mice. (A) PCR amplification of A phagocytophilum DNA in the blood of Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- mice and wild-type mice. A murine blood sample previously determined to contain A phagocytophilum DNA served as a positive control (indicated as “+”). (B) Percentage of peripheral blood neutrophils with morulae containing A phagocytophilum. Data are presented as the mean percentage (± SD) of morulae-positive neutrophils. The difference in the percentages of neutrophils infected for wild type mice versus Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- mice was statistically significant on days 5, 7, and 21 after infection (*P < .05). (C) Fc-Oxyburst assay of A phagocytophilum-infected murine leukocytes. Leukocytes from A phagocytophilum-infected Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- and control mice were incubated with Fc-Oxyburst immune complexes (10 μg/mL). The amount of oxidative species generated by the cells was measured as the fluorescence signal at 530 nm. Assays were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as the mean percentage (± SD) of NADPH oxidase competent cells. Representative data from at least 2 studies are presented.

A phagocytophilum infection is severely compromised in Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- mice. (A) PCR amplification of A phagocytophilum DNA in the blood of Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- mice and wild-type mice. A murine blood sample previously determined to contain A phagocytophilum DNA served as a positive control (indicated as “+”). (B) Percentage of peripheral blood neutrophils with morulae containing A phagocytophilum. Data are presented as the mean percentage (± SD) of morulae-positive neutrophils. The difference in the percentages of neutrophils infected for wild type mice versus Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- mice was statistically significant on days 5, 7, and 21 after infection (*P < .05). (C) Fc-Oxyburst assay of A phagocytophilum-infected murine leukocytes. Leukocytes from A phagocytophilum-infected Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- and control mice were incubated with Fc-Oxyburst immune complexes (10 μg/mL). The amount of oxidative species generated by the cells was measured as the fluorescence signal at 530 nm. Assays were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as the mean percentage (± SD) of NADPH oxidase competent cells. Representative data from at least 2 studies are presented.

A hallmark of A phagocytophilum infection is inhibition of the neutrophil respiratory burst.18-21 The Fc-Oxyburst assay was originally devised to identify NADPH oxidase-deficient neutrophils, on a cell-by-cell basis, from chronic granulomatous disease patients.56,57 We have demonstrated the applicability of this assay for indirectly identifying A phagocytophilum-infected neutrophils from HGE patients or experimentally infected mice or HL-60 cells based on the impairment of their NADPH oxidase.21 We therefore used this assay to examine the functional consequence of A phagocytophilum infection on neutrophil NADPH oxidase in Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- mice compared with wild-type mice. Peripheral blood neutrophils from A phagocytophilum-infected Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- mice exhibited no loss in oxidase activity (Figure 2C). On day 7 after challenge, the mean percentage of neutrophils from Fuc-TIV-/-/ Fuc-TVII-/- mice exhibiting a functional respiratory burst was identical to that of uninfected wild-type mice (90.8%) and uninfected Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- mice (89%) (data not shown). NADPH oxidase activity of neutrophils from infected wild-type mice, however, showed considerable impairment, with only 67% reacting with the Fc-Oxyburst reagent. By day 28, when A phagocytophilum infection had waned, 78% of neutrophils from control mice had recovered in their ability to generate

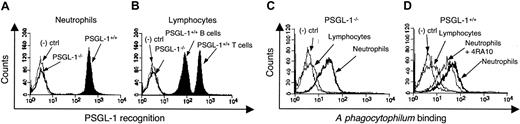

A phagocytophilum binds effectively to PSGL-1-/- murine neutrophils

The presence of α1,3-fucosylated PSGL-1 is thought to be essential for A phagocytophilum binding to and invasion of human neutrophils.22 Our studies using Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- mice demonstrate that murine A phagocytophilum infection, like human infection, requires α1,3-fucosyltransferase. We next sought to determine whether PSGL-1 is required for A phagocytophilum binding to murine neutrophils using leukocytes from PSGL-1-/- and wild-type mice. Rat mAb 2PH1, which recognizes murine PSGL-1, confirmed the absence of PSGL-1 in PSGL-1-/- mice and demonstrated its distribution on wild-type murine neutrophils (GR-1 gated) and lymphocytes (CD3 and CD19 gated) (Figure 3A-B). CHO cells were used as negative controls because they do not express PSGL-1 or fucosylated glycans37 and, consequently, A phagocytophilum cannot infect them. To assess bacterial binding in the absence of PSGL-1, neutrophils from PSGL-1-/- and control mice were incubated with CellTracker Green-labeled, PFA-fixed A phagocytophilum and assessed by flow cytometry. A phagocytophilum bound to PSGL-1-/- neutrophils with an MFI of 38.3 ± 4.2 (Figure 3C), whereas binding to control neutrophils yielded an MFI of 53.0 ± 6.1 (Figure 3D). Thus, in contrast to that observed for Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- neutrophils, A phagocytophilum effectively binds to PSGL-1-/- neutrophils. Anti-murine PSGL-1 mAb 4RA10, which blocks binding of P-selectin to murine PSGL-1,55 inhibited A phagocytophilum binding to PSGL-1+/+ neutrophils to the same level as PSGL-1-/- neutrophils (MFI of 40.5 ± 5.6, representing a 23.6% reduction; Figure 3D). These data demonstrate that PSGL-1 on murine neutrophils is not a major ligand for A phagocytophilum. The concordant results with PSGL-1-/- neutrophils and wild-type neutrophils treated with anti-PSGL-1 mAbs indicate that genetic deletion of PSGL-1 did not cause a compensatory increase in synthesis of an alternative ligand(s) for A phagocytophilum.

Binding of A phagocytophilum to murine PSGL-1-/- and wild-type leukocytes. Flow cytometric analysis of PE-conjugated anti-PSGL-1 mAb 2PH1 binding to PSGL-1-/- or control neutrophils (A) and lymphocytes (B). Flow cytometric analysis of Cell Tracker Green-labeled, PFA-fixed A phagocytophilum binding to lymphocytes and neutrophils from PSGL-1-/- (C) or control (D) mice. In panel D, control neutrophils were also pretreated with anti-murine PSGL-1 mAb 4RA10. Assays were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as the mean percentage (± SD) of leukocytes bound by 2PH1 or bacteria. CHO cells were used as a negative control in all experiments. Representative data from at least 2 studies are shown.

Binding of A phagocytophilum to murine PSGL-1-/- and wild-type leukocytes. Flow cytometric analysis of PE-conjugated anti-PSGL-1 mAb 2PH1 binding to PSGL-1-/- or control neutrophils (A) and lymphocytes (B). Flow cytometric analysis of Cell Tracker Green-labeled, PFA-fixed A phagocytophilum binding to lymphocytes and neutrophils from PSGL-1-/- (C) or control (D) mice. In panel D, control neutrophils were also pretreated with anti-murine PSGL-1 mAb 4RA10. Assays were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as the mean percentage (± SD) of leukocytes bound by 2PH1 or bacteria. CHO cells were used as a negative control in all experiments. Representative data from at least 2 studies are shown.

Sialidase treatment reduces A phagocytophilum binding to wild-type and PSGL-1-/- murine neutrophils

Enzymatic removal of sialic acid residues on human HL-60 cells markedly inhibits A phagocytophilum binding and infection.23 To understand whether sialic acid residues are involved in A phagocytophilum binding to murine neutrophils, PSGL-1-/- or wild-type neutrophils were treated with sialidases prior to incubation with CellTracker Green-labeled, PFA-fixed A phagocytophilum. The mAb 2H5 recognizes sLex and other sialylated but nonfucosylated epitopes. This antibody bound equally well to PSGL-1-/- and control neutrophils (Figure 4A). Pretreatment with sialidase abolished 2H5 binding, confirming the activity of the sialidases (Figure 4B). Sialidase treatment significantly reduced, but did not eliminate, binding of A phagocytophilum to PSGL-1-/- (Figure 4C) and control (Figure 4D) murine neutrophils.

The effect of sialidase treatment on A phagocytophilum binding to PSGL-1-/- and wild-type murine neutrophils. Binding of FITC-labeled mAb 2H5, which recognizes a subset of sialylated glycans, to PSGL-1-/- and control neutrophils before (A) and after (B) sialidase treatment. Binding of Cell Tracker Green-labeled, PFA-fixed A phagocytophilum to sialidase-treated and untreated neutrophils from PSGL-1-/- (C) or control (D) mice. Assays were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as the mean percentage (± SD) of neutrophils bound by 2H5 or bacteria. Representative data from at least 2 studies are presented.

The effect of sialidase treatment on A phagocytophilum binding to PSGL-1-/- and wild-type murine neutrophils. Binding of FITC-labeled mAb 2H5, which recognizes a subset of sialylated glycans, to PSGL-1-/- and control neutrophils before (A) and after (B) sialidase treatment. Binding of Cell Tracker Green-labeled, PFA-fixed A phagocytophilum to sialidase-treated and untreated neutrophils from PSGL-1-/- (C) or control (D) mice. Assays were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as the mean percentage (± SD) of neutrophils bound by 2H5 or bacteria. Representative data from at least 2 studies are presented.

A phagocytophilum infection of PSGL-1-/- mice exhibits no difference from infection of wild-type mice

After observing that PSGL-1 is not an essential ligand for A phagocytophilum to bind murine neutrophils, we sought to define the contribution of PSGL-1 to in vivo infection. Groups of PSGL-1-/- and wild-type mice were challenged with A phagocytophilum and monitored for infection. As indicated in Figure 5A, the kinetics of A phagocytophilum infection between wild-type and PSGL-1-/- mice was highly similar. All 3 PSGL-1-/- mice and 2 of the 3 control mouse samples yielded amplicons on day 3 (Figure 5A). Blood samples were strongly positive for A phagocytophilum for all mice on day 7. On day 15 the bacterial burden was higher for PSGL-1-/- mice. This is likely due to the fact that PSGL-1 deficiency results in leukocytosis,32 which would effectively provide greater numbers of neutrophils for A phagocytophilum infection.

A phagocytophilum infection of PSGL-1-/- mice is similar to that of wild-type mice. (A) PCR amplification of A phagocytophilum DNA in the blood of PSGL-1-/- mice and control littermates. (B) Percentage of peripheral blood neutrophils with morulae containing A phagocytophilum. Data are presented as the mean percentage (± SD) of neutrophils with morulae. (C) Fc-Oxyburst assay of A phagocytophilum-infected murine blood leukocytes. As-says were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as the mean percentage (± SD) of NADPH oxidase competent cells. Representative data from at least 2 studies are presented.

A phagocytophilum infection of PSGL-1-/- mice is similar to that of wild-type mice. (A) PCR amplification of A phagocytophilum DNA in the blood of PSGL-1-/- mice and control littermates. (B) Percentage of peripheral blood neutrophils with morulae containing A phagocytophilum. Data are presented as the mean percentage (± SD) of neutrophils with morulae. (C) Fc-Oxyburst assay of A phagocytophilum-infected murine blood leukocytes. As-says were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as the mean percentage (± SD) of NADPH oxidase competent cells. Representative data from at least 2 studies are presented.

The percentage of peripheral blood neutrophils with morulae was consistent with the PCR results (Figure 5B). On day 3 after inoculation, the mean percentage of neutrophils with morulae was 0.2% for control mice and 0.3% for PSGL-1-/- mice. On day 7, 5.8% of wild-type and 7.7% for PSGL-1-/- mice had discernible morulae. On day 15, 0.6% of control neutrophils and 2% of PSGL-1-/- neutrophils were colonized. Morulae were not evident in any of the control or experimental mice on days 21 and 28.

On the peak day of infection (day 7), both control and PSGL-1-/- mice had comparable degrees of reduction in NADPH oxidase (Figure 5C). Ninety-five percent of neutrophils from uninfected mice had a detectable respiratory burst, whereas 40% of A phagocytophilum-infected wild-type and 43.5% of the infected PSGL-1-/- mice produced superoxide (

A phagocytophilum binds better to human PSGL-1 than to murine PSGL-1

There is much more PSGL-1-independent binding of A phagocytophilum to murine neutrophils than to human neutrophils. To directly compare the ability of A phagocytophilum to interact with human and murine PSGL-1, we measured binding to transfected CHO cells expressing either human or murine PSGL-1. Both cells coexpress FTVII and core-2-β1-6-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase, which are required to glycosylate PSGL-1 such that it binds to P-selectin.46,54 CHO cells appeared to express at least 10-fold more murine PSGL-1 than human PSGL-1 (Figure 6A-B), although an exact comparison of surface density could not be made since different FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies were required to detect the murine anti-human PSGL-1 mAb PL1 and the rat anti-murine PSGL-1 mAb 4RA10. Both cell types expressed equivalent densities of sLex, indicating comparable posttranslational modification (Figure 6C). Despite the higher density of murine PSGL-1, significantly fewer A phagocytophilum bound to cells expressing murine PSGL-1 than to cells expressing human PSGL-1 (Figure 6D). The low-level binding to murine PSGL-1 was specific because anti-murine mAb 4RA10 almost completely blocked binding. These data demonstrate that A phagocytophilum binds much better to human PSGL-1 than to murine PSGL-1, even in the same cell type with the same posttranslational modifications.

A phagocytophilum binds better to human PSGL-1 than to murine PSGL-1. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of binding of anti-human PSGL-1 mAb PL-1 or isotype-matched control mAb to transfected CHO cells expressing human PSGL-1. Bound mAb was detected with FITC-labeled goat antimouse IgG. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of binding of anti-murine PSGL-1 mAb 4RA10 or isotype-matched controls to transfected CHO cells expressing murine PSGL-1. Bound mAb was detected with FITC-labeled goat anti-rat IgG. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of binding of anti-sLex mAb HECA-452 or matched isotype control mAb to transfected CHO cells expressing either human or murine PSGL-1. Bound mAb was detected with FITC-labeled goat antirat IgM. (D) Flow cytometric analysis of CellTracker Green-labeled, PFA-fixed A phagocytophilum binding to nontransfected CHO cells, to murine PSGL-1-expressing CHO cells, to murine PSGL-1-expressing CHO cells pretreated with 4RA10, or to human PSGL-1-expressing CHO cells. Assays were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as the mean percentage (± SD) of cells bound by antibody or bacteria. Representative data from at least 2 studies are presented.

A phagocytophilum binds better to human PSGL-1 than to murine PSGL-1. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of binding of anti-human PSGL-1 mAb PL-1 or isotype-matched control mAb to transfected CHO cells expressing human PSGL-1. Bound mAb was detected with FITC-labeled goat antimouse IgG. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of binding of anti-murine PSGL-1 mAb 4RA10 or isotype-matched controls to transfected CHO cells expressing murine PSGL-1. Bound mAb was detected with FITC-labeled goat anti-rat IgG. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of binding of anti-sLex mAb HECA-452 or matched isotype control mAb to transfected CHO cells expressing either human or murine PSGL-1. Bound mAb was detected with FITC-labeled goat antirat IgM. (D) Flow cytometric analysis of CellTracker Green-labeled, PFA-fixed A phagocytophilum binding to nontransfected CHO cells, to murine PSGL-1-expressing CHO cells, to murine PSGL-1-expressing CHO cells pretreated with 4RA10, or to human PSGL-1-expressing CHO cells. Assays were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as the mean percentage (± SD) of cells bound by antibody or bacteria. Representative data from at least 2 studies are presented.

A phagocytophilum induces less chemokine secretion from Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- neutrophils than from PSGL-1-/- neutrophils

Incubation of wild-type murine neutrophils with A phagocytophilum induces the secretion of chemokines KC and MIP-2.53 As an additional means of assessing the role of PSGL-1 versus α1,3-fucosylation in murine infection, we assayed chemokine induction by PSGL-1-/-, Fuc-TIV-/-/FucT-VII-/-, or control murine neutrophils following incubation with A phagocytophilum. Bacteria were added at multiplicities of infection (MOI) of 4000, 400, and 40. Neutrophils incubated with lysed HL-60 cells served as a negative control. To assess whether observable differences in chemokine levels were A phagocytophilum specific, neutrophils were also incubated with LPS. Twenty-four hours following the addition of bacteria, neutrophils from PSGL-1-/- mice produced higher levels of MIP-2 and KC compared with those from control littermates (Figure 7A-B). Lack of α1,3-fucosylation, however, dampened the effect A phagocytophilum had on chemokine induction. As bacterial concentrations were reduced from apparently saturating to subsaturating levels, the Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- neutrophils exhibited as much as a 5-fold reduction in MIP-2 secretion compared with that of control mice (Figure 7C). Similarly, at a ratio of 40 A phagocytophilum per cell, the Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- neutrophils secreted 4.6-fold less KC compared with controls (after normalization according to the LPS control; Figure 7D). In all instances, chemokine levels directly correlated with bacterial load.

MIP-2 and KC levels in A phagocytophilum-infected murine neutrophil culture supernatants. Host cell-free A phagocytophilum were added to neutrophil cultures from PSGL-1-/-, Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/-, and control mice at ratios of 4000, 400, and 40 bacteria per neutrophil. Twenty-four hours after incubation, MIP-2 (A,C) and KC (B,D) levels were measured. Assays were performed in triplicate. Results are presented as the mean ± SD of chemokine produced. Statistically significant differences in chemokine levels are indicated by * (P < .06). Representative data from at least 4 independent experiments are shown.

MIP-2 and KC levels in A phagocytophilum-infected murine neutrophil culture supernatants. Host cell-free A phagocytophilum were added to neutrophil cultures from PSGL-1-/-, Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/-, and control mice at ratios of 4000, 400, and 40 bacteria per neutrophil. Twenty-four hours after incubation, MIP-2 (A,C) and KC (B,D) levels were measured. Assays were performed in triplicate. Results are presented as the mean ± SD of chemokine produced. Statistically significant differences in chemokine levels are indicated by * (P < .06). Representative data from at least 4 independent experiments are shown.

Discussion

A phagocytophilum infects both humans and mice, although mice are a natural reservoir for infection. In both species, the hallmark of infection is the colonization of neutrophils, which alters neutrophil functions.1,9 A phagocytophilum usurps features of selectin ligands on human neutrophils to enable binding and infection in vitro. These features include expression of PSGL-1, sialic acid residues, and α1,3-fucosylated glycans.22,23 Here we asked whether A phagocytophilum uses a similar strategy to bind to and infect murine neutrophils in vitro and further studied whether infection in vivo requires selectin ligands on murine neutrophils. Our data demonstrate that binding and productive infection of murine neutrophils requires expression of sialic acid and α1,3-fucosylated glycans but not PSGL-1 expression. The differential usage of PSGL-1 has important implications for understanding how A phagocytophilum propagates infection in humans and mice.

Fixation of labeled A phagocytophilum allowed direct measurement of binding of bacteria to murine neutrophils without the variables of internalization or alteration of neutrophil functions. We observed that pretreating murine neutrophils with sialidases signifi-cantly diminished, but did not eliminate, binding. In previous studies, sialidase treatment of human HL-60 cells abolished nearly all binding.23 Thus, binding of A phagocytophilum requires that both murine and human neutrophils be sialylated. The residual binding to sialidase-treated murine neutrophils could represent sialic acid-independent ligands or the failure of sialidase to remove some sialic residues on ligands for A phagocytophilum.

Fuc-TIV and Fuc-TVII are the α1,3-fucosyltransferases expressed in murine leukocytes,25 and leukocytes from Fuc-TIV-/-/ Fuc-TVII-/- mice do not interact with selectins.29,30 Therefore, these leukocytes presumably do not express α1,3-fucosylated glycans. Binding of fixed A phagocytophilum to Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- neutrophils was nearly abolished. Similarly, Fuc-TIV-/-/ Fuc-TVII-/- mice were much less susceptible to infection in vivo. Small numbers of neutrophils were transiently colonized, as measured by the microscopic detection of morulae and by PCR amplification of A phagocytophilum DNA. This low-level infection, however, did not translate into impairment of neutrophil NAPDH oxidase activity. In vitro binding of A phagocytophilum to human myeloid cells requires α1,3-fucosyltransferase activity.22,23 The data here extend this requirement to murine neutrophils and further demonstrate that productive infection in vivo requires expression of α1,3-fucosyltransferase in neutrophils and cognate α1,3-fucosylated glycans.

A phagocytophilum must also interact with PSGL-1 to bind and infect human neutrophils in vitro.22 In sharp contrast, we found that A phagocytophilum bound nearly as well to PSGL-1-/- murine neutrophils as to wild-type murine neutrophils in vitro. More significantly, in vivo infection with A phagocytophilum resulted in colonization of similar numbers of neutrophils in wild-type and PSGL-1-/- mice, produced comparable defects in NAPDH oxidase activity, and similarly induced chemokine production. Therefore, A phagocytophilum does not require PSGL-1 to bind or infect murine neutrophils in vitro or in vivo.

Loss of α1,3-fucosyltransferase activity in neutrophils considerably reduces their ability to produce MIP-2 and KC after exposure to A phagocytophilum. This is possibly because the bacterium does not adequately bind to the appropriate ligand(s) required for adhesion and/or invasion and/or chemokine induction. The fact that secretion of MIP-2 and KC from Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- neutrophils was not abolished may be due to the nature of the assay. Indeed, the assay strongly favored bacteria-host cell interactions as high concentrations of A phagocytophilum were seeded onto adhered neutrophils in the absence of the flow conditions normally encountered in the mammalian bloodstream. The nonspecific interactions that were presumably favored may have been substantial enough to enable A phagocytophilum to induce chemokine production. Alternatively, an as yet undefined nonfucosylated ligand may be involved in this process.

A phagocytophilum binds poorly to murine PSGL-1, as demonstrated by its much weaker binding to CHO cells expressing murine PSGL-1 versus those expressing human PSGL-1. This suggests that there are structural differences between human and murine PSGL-1 that affect binding. Indeed, there are considerable differences in the amino acid sequences of the N-terminal regions of human and murine PSGL-1, although both still bind to P-selectin.58,59 Murine neutrophils also express many fewer fucosylated epitopes for mAbs to sLex and related structures, yet they retain P-selectin binding.46 However, we observed that A phagocytophilum binds better to human PSGL-1 than to murine PSGL-1, even when each is expressed in transfected CHO cells with comparable FTVII activities. Thus, while differential glycosylation of PSGL-1 may partially account for the lesser contribution of PSGL-1 to A phagocytophilum binding to murine neutrophils, it is unlikely a major factor.

Our data indicate that A phagocytophilum uses related, yet distinct forms of selectin mimicry to infect human and murine neutrophils. What does this imply for the molecular mechanisms of infection? P-selectin binds with very low affinity to sLex on many glycoconjugates.25,60,61 Under physiologic conditions, however, it binds preferentially to the N-terminus of PSGL-1 on both human and murine leukocytes.26,60,61 This occurs because the N-terminal region of PSGL-1 presents peptide and tyrosine sulfate residues as well as sLex on a particular O-glycan, which interact cooperatively with the lectin domain of P-selectin.26,35,36,42-45 A phagocytophilum has been suggested to bind to the N-terminus of human PSGL-1 by a related mechanism. This was supported by the ability of mAbs to the N-terminal region of PGSL-1 to inhibit binding to and infection of human neutrophils and HL-60 cells.22 Furthermore, coexpression of human PSGL-1 and Fuc-TVII, but not either protein alone, rendered transfected heterologous cells susceptible to binding and infection with A phagocytophilum. Binding was also inhibited by mAbs to the N-terminus of human PSGL-1.22 These data were interpreted to indicate that A phagocytophilum binds specifically to fucosylated human PSGL-1, presumably near the N-terminus. This model suggests the bacterium expresses an adhesin with features sufficiently like P-selectin to bind to a very limited region of human PSGL-1. This putative adhesin, however, either cannot interact with murine PSGL-1, or the interaction is not required because A phagocytophilum also recognizes a PSGL-1-independent but α1,3-fucosyltransferase-dependent ligand(s) on murine but not human neutrophils.

An alternative model is that A phagocytophilum expresses at least 2 adhesins, which bind cooperatively to at least 2 ligands on both human and murine neutrophils. One adhesin might bind to α1,3-fucosylated and perhaps α2,3-sialylated glycans; these might be attached to many cell surface glycoproteins or glycolipids. A second adhesin might bind to an N-terminal peptide component of human PSGL-1. The same adhesin might recognize a structurally related region on a different protein on murine neutrophils. A third adhesin might bind to yet another ligand found on murine, but not human, neutrophils. In this model, the bacterium uses the same adhesin to bind α1,3-fucosylated glycans on both human and murine neutrophils. Productive binding and infection, however, requires one or more additional adhesins; these would interact with one or more ligands that need not be shared by human and murine neutrophils.

There are precedents of bacteria using multiple adhesins to diversify their host repertoire. For example, Listeria monocytogenes binding and entry of mammalian cells are facilitated through ligand mimicry of several receptors, which include E-cadherin, c-Met, gC1q-R, and proteoglycans. Of these, usage of E-cadherin, which is expressed on gut epithelial cells, is specific to human but not murine infection. Despite being 85% similar to human E-cadherin, a single amino acid difference in the targeted domain of mouse E-cadherin prevents L monocytogenes from invading the epithelial cells. This difference translates into the inability of L monocytogenes to establish murine infection via oral inoculation, in contrast to human infection.62 Uropathogenic E coli uses variants of PapG, an adhesin located at the tip of its P pilus, to attach to kidney epithelial cells through host-specific glycolipid receptors. PapGII, which is linked to human infection, facilitates binding to GbO4, the predominant galabiose-containing isoreceptor of human uroepithelial cells. Similarly, PapGIII specifically mediates canine infection through its interaction with GbO5, the major isoform expressed on canine kidney cells.63

Testing models of molecular recognition by A phagocytophilum will require, in part, measuring binding of A phagocytophilum to a panel of selectin ligands and other candidate ligands on human and murine neutrophils. Such information may guide further studies to identify the different molecules that A phagocytophilum uses to infect mice, its natural host, and humans, its inadvertent victim.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, July 17, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0621.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI041440 (E.F.), AI10554 (J.A.C.), AI48075 (R.D.C.), HL 65631 (R.P.M.), the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (E.F.), and a J. Kempner Postdoctoral Fellowship (T.W.).

J.A.C. and M.A. contributed equally to this study.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked ”advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Drs John B. Lowe and Robert J. Kelly of the University of Michigan Medical School for providing the Fuc-TIV-/-/Fuc-TVII-/- mice; Dr Paul Vestweber for providing mAb 4RA10; Debbie Beck for excellent technical assistance; and Dr Venetta Thomas for helpful discussions.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal