Abstract

The chimeric MLL-EEN fusion protein is created as a result of chromosomal translocation t(11;19)(q23;p13). EEN, an Src homology 3 (SH3) domain–containing protein in the endophilin family, has been implicated in endocytosis, although little is known about its role in leukemogenesis mediated by the MLL-EEN fusion protein. In this study, we have identified and characterized EBP, a novel EEN binding protein that interacts with the SH3 domain of EEN through a proline-rich motif PPERP. EBP is a ubiquitous protein that is normally expressed in the cytoplasm but is recruited to the nucleus by MLL-EEN with a punctate localization pattern characteristic of the MLL chimeric proteins. EBP interacts simultaneously with EEN and Sos, a guanine-nucleotide exchange factor for Ras. Coexpressoin of EBP with EEN leads to suppression of Ras-induced cellular transformation and Ras-mediated activation of Elk-1. Taken together, our findings suggest a new mechanism for MLL-EEN–mediated leukemogenesis in which MLL-EEN interferes with the Ras-suppressing activities of EBP through direct interaction.

Introduction

Chromosomal translocations that disrupt the human homolog of the Drosophila thrithorax (TRX) gene, MLL (mixed lineage leukemia) gene at 11q23, are frequently found in human leukemias.1-3 TRX is a transcriptional activator required to maintain expression of homeotic genes during Drosophila embryonic development.4,5 Knock-out studies in mice have shown that MLL, like TRX in Drosophila, has a similar function in mammals with MLL heterozygous mice showing abnormal skeletal and hemopoietic development.6,7 MLL encodes for a protein of 3968 amino acids with structurally complex domains. In the N-terminus there are 3 AT hook motifs and a cysteine-rich region (CxxC motif), which is homologous to mammalian DNA methyltransferase and is responsible for DNA binding.8 Regions of conservation between MLL and TRX are located in the internal plant homeodomain zinc fingers and the C-terminal SET domain. Both domains are thought to function in protein-protein interaction and chromatin modification.9,10

Translocations of the MLL result in formation of chimeric proteins in which the N-terminus of MLL is fused in-frame to the C-terminus of fusion partners. There are at least 35 MLL fusion partners identified to date—although diverse in structure and function, they can be classified into families or groups. A group of nuclear fusion partners, including AF4, AF9, AF10, ENL, ELL, AF17, AFX1, AF6q21, CBP, and P300, has been implicated in various aspects of transcriptional regulation. The remaining group of cytoplasmic fusion partners, including AF6, AF1p, Abi-1, EEN, and FBP17, possesses structural domains responsible for protein-protein interaction.11 While direct fusion with transcriptional effector domains resulting in aberrant transcriptional activation activities may represent a common oncogenic mechanism for certain MLL–nuclear fusion proteins,12-18 the leukemogenic mechanisms mediated by MLL–cytoplasmic fusion proteins are still largely unknown.19-21

EEN, an Src homology 3 (SH3) domain–containing gene of the endophilin family localized on chromosome 19p13, is fused to MLL as a result of t(11;19) chromosomal translocation in a case of infant acute myeloid leukemia.22 EEN and its 2 related family members, EEN-B1 and EEN-B2, also known as endophilins II, I, and III, respectively, shared the SH3 domains that are closely related to the SH3 domain of the adaptor protein Grb2.23-25 All 3 members have been reported to be binding partners of endocytic proteins, synaptojanin, dynamin, and amphiphysins, which are implicated in the trafficking of synaptic vesicles in the presynaptic nerve terminal24-28 and with the G protein–coupled β1-adrenergic receptor.29 Unlike EEN-B1 and EEN-B2, which show restricted tissue expression mainly in the brain, EEN is ubiquitously expressed.30 Little is known on the function of EEN in hematopoietic cells and the role played by EEN in MLL-EEN–mediated leukemogenesis.

In this study, we describe the identification of a cytoplasmic protein designated EBP (for EEN binding protein) that specifically interacts with EEN in the cytoplasm. We show that expression of MLL-EEN results in relocation of EBP from the cytoplasm into the nucleus to produce a distinct punctate pattern typical of MLL fusion proteins.31,32 Our results also show that EBP possesses inhibitory effect on Ras signaling and cellular transformation induced by Ras, a property of probable biologic significance and relevance in the context of MLL-EEN–mediated leukemogenesis.

Materials and methods

Plasmid constructions

Various expression constructs using pAS2-1, pGADGH, pGEX1, pFLAG.CMV2, and pCS2+MT were prepared by standard molecular biology techniques and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the described fragments. Gal4 DNA-binding (BD) vector, pAS2-1, carrying EEN with the following amino acids were made: EEN 1-368 full-length (FL), 1-266 N-terminus coiled coil (NCC), 131-368 (CCSH3), 131-266 (CC) and 303-368 (SH3), EENB1 1-352 (FL) and EENB2 1-347 (FL). Gal4-BD vectors of EBP fragments 1-767 (FL) and SH3 domains (A, B, C, and D) were also constructed. Gal4 activation domain (AD) vector, pGADGH, carrying EBP with the following amino acids was constructed: EBP 1-767, 76-767, 94-767, 94-357, 532-767, 272-666, 272-533, 272-358, 272-342, 348-419, and Δ343-347 (272-533 with internal 343-347 deletion). Fragment of Sos2-C (amino acids 974-1262) was cloned into Gal4-AD. Plasmids for bacterial expression of glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein were made using pGEX1: EEN 303-368 (SH3 domain), EBP 272-358, and EBP 348-419. Eukaryotic expression vector, pCS2+MT, of Myc-tagged proteins was prepared as follows: EBP 1-767, 76-767, 1-358, and 532-767 and Sos2-C (amino acids 974-1262). FLAG-tagged expression vector, pFLAG-CMV-2 (Sigma, St Louis, MO) carrying EEN, EEN deletion mutants, EENΔSH3, EEN with nuclear localization signal (NLS), NLSEEN and NLSEENΔSH3 and MLL-EEN were constructed.

Yeast 2-hybrid library screening and binding assay

Yeast strain Y190 was first transformed with the bait, EEN1-368pAS2-1 plasmid carrying full-length EEN fused to Gal4-BD, and subsequently with the HeLa cell cDNA library (BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) constructed in the Gal4-AD plasmid, pGADGH by large-scale lithium acetate transformation protocol. The transformation mixture was spread on SD/-Trp/-Leu/-His plates, and isolated positive clones carrying potential EEN interaction proteins were assayed for β-galactosidase activity on filters. The library plasmids were recovered from the positive colonies and were sequenced. To test the interacting potential between 2 known proteins, yeast strain SFY562 was cotransformed with Gal4-BD and Gal4-AD constructs carrying the potential interacting proteins. Transformation mixtures were spread on plates with SD/-Trp/-Leu for selection of cotransformants, and qualitative colony lift filter assay was performed. For the quantitative interaction assay, the cotransformants were lysed and the β-galactosidase activity was quantified using the substrate o-nitrophenyl β-D-galactopyranoside (ONPG).

Tissue expression study by polymerase chain reaction

The expression of EBP on a panel of human multiple tissue cDNA (BD Biosciences Clontech) was examined by PCR. In each reaction, 0.2 ng human cDNA was amplified with 10 pmol of each EBP gene–specific primer, EBP348F (5′-CCTCCCCCAAAGCTTTCT-3′) and EBP419R (5′-AAGTACATCCCCACGCAT-3′). Normalization of tissue cDNA panel was achieved through amplification of actin.

Cell culture and transfection

HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum, penicillin, and streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 in air. Rat 6 (R6) cells33 were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% calf serum. Transfection of cells was performed by standard calcium phosphate precipitation protocol. Semiconfluent cells in 100-mm plates were transfected with 20 μg plasmid DNA for 16 hours and harvested after 48 hours. For immunofluorescence staining, cells seeded on coverslips in 35-mm plates were transfected by using Fugene 6 reagent according to the manufacturer's instruction (Roche, Mannheim, Germany).

Coimmunoprecipitation

Transfection cells were harvested, washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and lysed on ice in NET buffer (150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA [ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid], 50 mM Tris [tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane] [pH 7.4], 1 × complete protease inhibitors [Roche], 1% Nonidet P-40 [NP-40]). Lysed cells were cleared by centrifugation, and supernatants were collected. Protein concentration was determined by Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). For coimmunoprecipitation of Myc-tagged EBP and FLAG-tagged EEN, supernatants were incubated with anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma) overnight at 4°C, after which immunoprecipitates were collected with protein A–Sepharose for 4 hours at 4°C with constant rotation. The beads were washed 5 times with NET lysis buffer and boiled in sample buffer. The immunoprecipitates were subjected to 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and the proteins were transferred to Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Western blots were probed by anti-Myc antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody and then visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ).

Glutathione (GST) pull-down assay

GST fusion proteins of EEN SH3 domain and EBP proline-rich region were expressed in host strain BL21(DE3). Expression of fusion proteins was induced upon the addition of isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 0.1 mM in exponentially growing bacterial cultures at 37°C for 3 hours. Bacteria were collected and lysed, and fusion proteins were purified on glutathione Sepharose beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Cell lysates prepared as described above were incubated with 5 μg GST fusion proteins immobilized on glutathione Sepharose beads for 2 hours at 4°C with constant rotation. The beads were washed with NET buffer, and bound proteins were eluted and prepared for Western blot analysis. Bound proteins were detected by anti-Myc antibody.

Immunofluorescent staining

Cells grown on coverslips were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes. Cells were then blocked with 5% goat serum in PBS and incubated with primary antibodies (rabbit anti-Myc or mouse anti-FLAG antibodies) for 1 hour, followed by secondary antibodies (antirabbit fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]–conjugated or antimouse rhodamine-conjugated) (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) for 45 minutes with extensive washing in between. Cells were counterstained with DAPI (4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole) (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) and mounted in Vectashield antifade mountant (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Images were captured under magnification of × 1000 by a fluorescence microscope equipped with a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

Luciferase assay

HeLa cells in 24-well plates were transfected with different combinations of plasmids using Fugene 6 reagent. Plasmids used included pCS2+MT-EBP, pCMV2-FLAG-EEN, pUSE-RasQ61L (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY), pGal4-luc, pFA-Elk-1 reporter constructs (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and an internal control pRLSV40. Total amount of expression vectors was equalized with the empty vector. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cell lysates were harvested, prepared, and assayed using Dual Luciferase Reporter assay system (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Transfection efficiency was normalized with the Renilla luciferase activity. Each transfection was done in triplicate, and 2 independent experiments were performed. Data were expressed as means with standard deviations. Statistical analysis was performed using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey test.

Soft agar assay

R6 cells stably transfected with empty vector, RasQ61L, RasQ61L+EBP, RasQ61L+EEN, RasQ61L+EBP+EEN, and RasQ61L+EBP+NLSEEN were suspended at 1 × 104 cells per 60-mm plate with 2 mL of 0.4% agar in DMEM containing 20% fetal calf serum and overlaid above a layer of 5 mL of 1% agar in the same medium. At day 14, colonies were stained with the vital stain 2-(P-iodopenyl)-3-(P-nitrophenyl)-5-phenyltetrazolium chloride hydrate for 48 hours at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator, and the numbers and sizes were scored. Representative colonies were photographed. Six plates were done for each group, and 2 independent experiments were performed. Data were calculated as means with standard deviations for each group. Statistical analysis was performed using 1-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey test.

Results

Identification and tissue expression of EBP

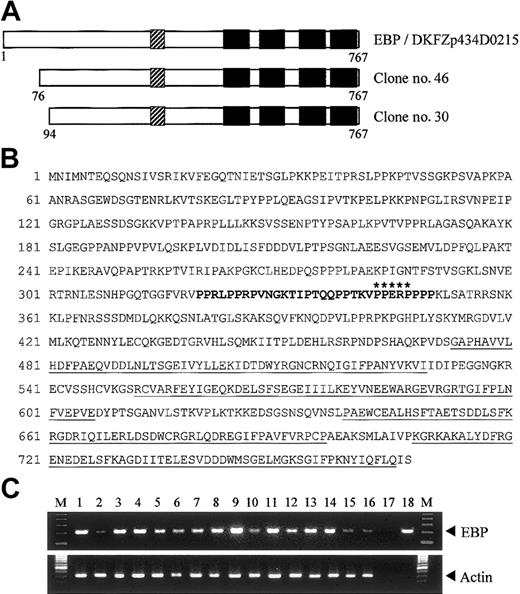

To search for potential binding partners of EEN, we performed yeast 2-hybrid screening of a HeLa cell cDNA library using the full-length EEN as bait. Two positive clones, no. 30 and no. 46, had identical nucleotide sequence. These 2 clones were identical to reported sequence DKFZp434D0215 (GenInfo Identifier [GI]: 27477709), which encodes a hypothetical protein of 767 amino acids (Figure 1A). Sequence alignment between our library-screened clones and the reported sequence revealed that our clones are partial clones with an incomplete N-terminal. We obtained the N-terminal fragment by PCR using HeLa cell cDNA as template. The full-length cDNA for the novel interacting partner of EEN, named EBP (EEN binding protein), was obtained. Structural analysis of EBP amino acid sequence revealed that it contained a proline-rich region (PRR) from amino acids 320-350 followed by 4 SH3 domains in the C-terminus (Figure 1A-B). To determine tissue distribution of EBP, the expression of EBP was studied by PCR analysis on various human tissue cDNAs. An expected amplified product of 213 base pair (bp) was obtained and sequenced. Similar to EEN that is ubiquitously expressed,30 EBP was detected in all adult and fetal tissues being tested (Figure 1C). The concomitant tissue distribution of EBP and EEN suggests that the 2 proteins are possibly to be binding partners in various tissues.

Structure and tissue expression of EBP. (A) Schematic representation of EBP. EBP encodes a protein of 767 amino acids and comprises a central proline-rich region (PRR) followed by 4 SH3 domains. The SH3 domains are indicated by black boxes, and the PRR is shown as hatched boxes. Clone nos. 30 and 46 were obtained from yeast 2-hybrid library screening. Reported sequence DKFZp434D0215 (GI: 27477709) that shows nucleotide sequence identity with EBP is aligned for comparison. (B) Deduced amino acid sequence of EBP. The PRR within amino acids 320-350 is boldfaced. Putative EEN-binding motif, PPERP in amino acids 343-347, is marked by asterisks. Four SH3 domains located in amino acids 473-529, 552-606, 639-696, and 708-765 are underlined. (C) Tissue expression of EBP. Analysis of EBP expression by PCR in multiple human adult (1-8) and fetal (9-16) tissue cDNAs. Arrowheads indicate specific PCR products amplified. PCR of actin is included as control. Heart (1,9), brain (2,10), placenta (3), lung (4,11), liver (5,12), skeletal muscle (6,13), kidney (7,14), pancreas (8), spleen (15), thymus (16), water (17), EBP plasmid DNA (18), 100-bp ladder marker (M).

Structure and tissue expression of EBP. (A) Schematic representation of EBP. EBP encodes a protein of 767 amino acids and comprises a central proline-rich region (PRR) followed by 4 SH3 domains. The SH3 domains are indicated by black boxes, and the PRR is shown as hatched boxes. Clone nos. 30 and 46 were obtained from yeast 2-hybrid library screening. Reported sequence DKFZp434D0215 (GI: 27477709) that shows nucleotide sequence identity with EBP is aligned for comparison. (B) Deduced amino acid sequence of EBP. The PRR within amino acids 320-350 is boldfaced. Putative EEN-binding motif, PPERP in amino acids 343-347, is marked by asterisks. Four SH3 domains located in amino acids 473-529, 552-606, 639-696, and 708-765 are underlined. (C) Tissue expression of EBP. Analysis of EBP expression by PCR in multiple human adult (1-8) and fetal (9-16) tissue cDNAs. Arrowheads indicate specific PCR products amplified. PCR of actin is included as control. Heart (1,9), brain (2,10), placenta (3), lung (4,11), liver (5,12), skeletal muscle (6,13), kidney (7,14), pancreas (8), spleen (15), thymus (16), water (17), EBP plasmid DNA (18), 100-bp ladder marker (M).

EEN SH3 domain is the EBP-interacting domain

Full-length EEN was used as bait in the yeast 2-hybrid library screening. Structurally, EEN comprises a central coiled coil domain and an SH3 domain in the C-terminus, which are domains responsible for protein-protein interaction.34 To map the minimal EBP-interacting domain of EEN, various EEN deletion fragments fused with the Gal4-BD in the pAS2-1 plasmid were cotransformed with clone no. 30, one of the positive clones of EBP, into the SFY562 yeast reporter strain (Figure 2A). Among the constructs tested, only the full-length EEN and mutants carrying the SH3 domain showed positive interaction with EBP (Table 1, Figure 2B). The SH3 domain of EEN was shown to be binding domain of EBP. The EBP-EEN interaction was further confirmed by an in vitro GST pull-down assay. Specific binding with Myc-tagged EBP was observed with the GST-EEN fusion protein containing the SH3 domain of EEN (GST-SH3) protein but not with the control GST protein (Figure 2C).

EEN SH3 domain mediates interaction with EBP. (A) Schematic representation of deletion mutants of EEN used in the yeast 2-hybrid transformation assay. The hatched box indicates the central coiled coil domain (CC), and the black box denotes the SH3 domain. FL and N represent the full-length and N-terminus of EEN, respectively. (B) Colony lift filter assay. Positive X-gal staining was observed in cotransformants expressing FL/clone no. 30 and SH3/clone no. 30 but not in negative controls, FL/pGADGH, and pAS2-1/clone no. 30. (C) GST pull-down assay. HeLa cells total cell lysate expressing Myc-tagged EBP was incubated with either GST or GST-SH3 (SH3 domain of EEN) immobilized on glutathione beads, and the bound proteins were detected with anti-Myc antibody. TCL indicates 10% of total cell lysate used in the assay.

EEN SH3 domain mediates interaction with EBP. (A) Schematic representation of deletion mutants of EEN used in the yeast 2-hybrid transformation assay. The hatched box indicates the central coiled coil domain (CC), and the black box denotes the SH3 domain. FL and N represent the full-length and N-terminus of EEN, respectively. (B) Colony lift filter assay. Positive X-gal staining was observed in cotransformants expressing FL/clone no. 30 and SH3/clone no. 30 but not in negative controls, FL/pGADGH, and pAS2-1/clone no. 30. (C) GST pull-down assay. HeLa cells total cell lysate expressing Myc-tagged EBP was incubated with either GST or GST-SH3 (SH3 domain of EEN) immobilized on glutathione beads, and the bound proteins were detected with anti-Myc antibody. TCL indicates 10% of total cell lysate used in the assay.

Yeast transformation assay

DNA-BD . | AD . | β-Galactosidase assay . |

|---|---|---|

| — | Clone no. 30 | - |

| FL | — | - |

| FL | Clone no. 30 | + |

| NCC | Clone no. 30 | - |

| CCSH3 | Clone no. 30 | + |

| CC | Clone no. 30 | - |

| SH3 | Clone no. 30 | + |

DNA-BD . | AD . | β-Galactosidase assay . |

|---|---|---|

| — | Clone no. 30 | - |

| FL | — | - |

| FL | Clone no. 30 | + |

| NCC | Clone no. 30 | - |

| CCSH3 | Clone no. 30 | + |

| CC | Clone no. 30 | - |

| SH3 | Clone no. 30 | + |

Deletion mutants of EEN fused to Gal4-BD in pAS2-1 plasmid were cotransformed with clone no. 30 fused to Gal4-AD in pGADGH plasmid into yeast strain SFY526. Colony lift filter assay was then performed on the cotransformants. Positive interaction is indicated by +, and no interaction is represented by -.

— indicates no proteins.

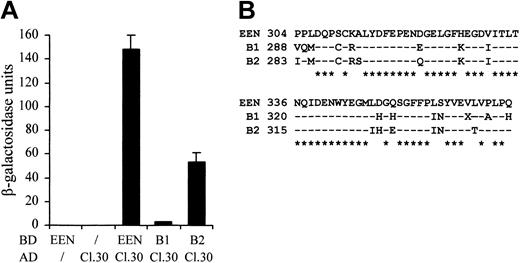

Differential interaction of EBP with EEN family members

Because the sequences of the SH3 domains are highly conserved among the EEN family members, we therefore examined whether the other 2 members, EEN-B1 and EEN-B2, could also interact with EBP. The colony lift filter assay showed that EBP positively interacted with EEN and EEN-B2, but interaction with EEN-B1 was barely detected (Table 2). The quantitative β-galactosidase assay further demonstrated that EBP had the strongest interaction with EEN (Figure 3A). Although EEN family members are known to interact with common proteins—for instance, synaptojanin, dynamin via the highly conserved SH3 domain30 —the discrepancies in SH3 domains' sequence identity between EEN, B1, and B2 might confer the binding specificity to each of the members (Figure 3B).

Yeast transformation assay of EBP with EEN family members

DNA-BD . | AD . | β-Galactosidase assay . |

|---|---|---|

| — | Clone no. 30 | - |

| EEN | — | - |

| EEN | Clone no. 30 | + |

| B1 | Clone no. 30 | - |

| B2 | Clone no. 30 | + |

DNA-BD . | AD . | β-Galactosidase assay . |

|---|---|---|

| — | Clone no. 30 | - |

| EEN | — | - |

| EEN | Clone no. 30 | + |

| B1 | Clone no. 30 | - |

| B2 | Clone no. 30 | + |

Clone no. 30 in Gal4-AD plasmid was cotransformed with each EEN family member, EEN, B1, and B2, cloned in Gal4-BD plasmid into yeast strain SFY526. Colony lift filter assay was then performed on the cotransformants. Positive interaction is indicated by +, and no interaction is represented by -.

— indicates no proteins.

Differential interaction of EBP with EEN family members. (A) Quantitative liquid culture assay. Lysates of cotransformants were quantified with ONPG substrate. Each data point represents the average ± SD of 3 independent experiments. (B) Amino acid alignment of the SH3 domains of EEN family members. Identical residues are indicated by dashes, and consensus residues among family are marked by asterisks.

Differential interaction of EBP with EEN family members. (A) Quantitative liquid culture assay. Lysates of cotransformants were quantified with ONPG substrate. Each data point represents the average ± SD of 3 independent experiments. (B) Amino acid alignment of the SH3 domains of EEN family members. Identical residues are indicated by dashes, and consensus residues among family are marked by asterisks.

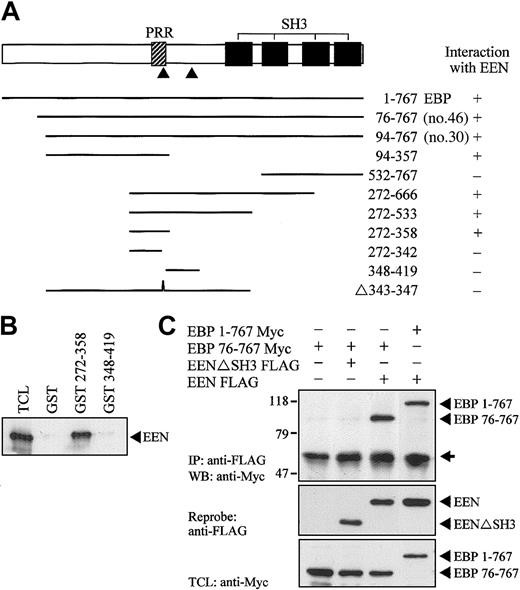

Proline-rich binding motif of EBP is required for interacting with EEN

Using yeast 2-hybrid cotransformation assay, we showed that full-length EBP was able to interact with EEN (Figure 4A). To map the interacting region of EBP for EEN, constructs carrying various deletion mutants of EBP fused with the Gal4-AD were constructed and cotransformed with EEN Gal4-BD plasmid into yeast strain SFY526. The minimal binding region of EEN was mapped to amino acids 342-358 of EBP. Within this minimal region, a putative EEN-binding motif, PPERP (amino acids 343-347), is located that matches the consensus proline-rich binding motif, PPXRP, previously reported to interact with the SH3 domain of endophilins/EEN.34 Interaction with EEN via the proline-rich motif in residues 343-347 was further confirmed by an internal deletion construct Δ343-347, which showed no interaction with EEN. Specific interaction between EEN with the proline-rich binding motif was confirmed by an in vitro GST pull-down assay (Figure 4B). In this experiment, Myc-tagged EEN expressed in HeLa cell lysate was pulled down by fragment of EBP (amino acids 272-358) containing the putative EEN-binding motif expressed as a GST fusion protein immobilized on glutathione beads. No interaction between EEN and another proline-rich sequence, PPRPKP, of EBP resides in amino acids 348-419 revealed that interaction between EEN and EBP was specifically mediated through the proline-rich binding motif, PPERP in amino acids 343-347. To explore the interaction of EEN and EBP in cultured cells, Myc-tagged full-length EBP (1-767) and partial EBP (76-767) were transiently transfected with either FLAG-tagged EEN or SH3 domain deletion mutant EENΔSH3 into HeLa cells. Myc-tagged EBP was coimmunoprecipitated with intact FLAG-tagged EEN. Deletion of the SH3 domain of EEN abrogated its interaction with EBP (Figure 4C).

Proline-rich motif of EBP is responsible for binding with EEN SH3 domain. (A) Yeast transformation assay of EBP with EEN. Schematic diagram of deletion constructs of EBP is shown. The PRR and SH3 domains are represented by hatched and black boxes, respectively. The arrowheads locate the putative prolinerich binding motifs, PPERP within amino acids 343-347 and PPRPKP within amino acids 400-405. Deletion mutants of EBP cloned in Gal4-AD plasmid were each cotransformed with EEN Gal4-BD plasmid into yeast strain SFY526. Positive interaction accessed by colony lift filter assay is indicated by +. (B) GST pull-down assay. Extract of HeLa cells expressing Myc-tagged EEN was incubated with GST, GST-EBP272-358, or GST-EBP348-419 immobilized on glutathione beads. Binding protein was detected with anti-Myc antibody. (C) Interaction of EBP with EEN in HeLa cells. Lysates of HeLa cells transfected with Myc-tagged EBP1-767 or EBP76-767 and/or FLAG-tagged EEN or SH3 domain deletion mutant, EENΔSH3 FLAG, were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-FLAG antibody followed by anti-Myc immunoblotting (WB). TCL was immunoblotted with anti-Myc antibody. The positions of immunoblotted proteins are indicated by arrowheads. The nonspecific immunoglobulin heavy chain is marked by an arrow.

Proline-rich motif of EBP is responsible for binding with EEN SH3 domain. (A) Yeast transformation assay of EBP with EEN. Schematic diagram of deletion constructs of EBP is shown. The PRR and SH3 domains are represented by hatched and black boxes, respectively. The arrowheads locate the putative prolinerich binding motifs, PPERP within amino acids 343-347 and PPRPKP within amino acids 400-405. Deletion mutants of EBP cloned in Gal4-AD plasmid were each cotransformed with EEN Gal4-BD plasmid into yeast strain SFY526. Positive interaction accessed by colony lift filter assay is indicated by +. (B) GST pull-down assay. Extract of HeLa cells expressing Myc-tagged EEN was incubated with GST, GST-EBP272-358, or GST-EBP348-419 immobilized on glutathione beads. Binding protein was detected with anti-Myc antibody. (C) Interaction of EBP with EEN in HeLa cells. Lysates of HeLa cells transfected with Myc-tagged EBP1-767 or EBP76-767 and/or FLAG-tagged EEN or SH3 domain deletion mutant, EENΔSH3 FLAG, were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-FLAG antibody followed by anti-Myc immunoblotting (WB). TCL was immunoblotted with anti-Myc antibody. The positions of immunoblotted proteins are indicated by arrowheads. The nonspecific immunoglobulin heavy chain is marked by an arrow.

EBP colocalizes and interacts with EEN in HeLa cells

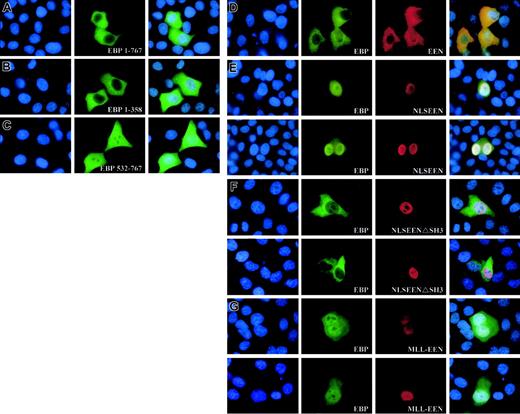

To determine the subcellular localization of EBP, Myc-tagged EBP was transiently transfected into HeLa cells. The expression of the Myc-tagged proteins in transfected cells was visualized by anti-Myc antibody followed by FITC-conjugated antibody. EBP was observed to be evenly distributed in the cytoplasm (Figure 5A). The N-terminal of EBP from amino acids 1-358, including the prolinerich region, also displayed similar cytoplasmic localization when transiently expressed in the HeLa cells (Figure 5B). However, the C-terminal of EBP from amino acids 532-767 consisting of the last 3 SH3 domains showed localization both in the cytoplasm with a uniform pattern and also in the nucleus with a punctate distribution (Figure 5C). This observation could be the result of the loss of structural domain, located within the N-terminal domain, that is responsible for retaining EBP in the cytoplasm.

Expression of EEN and MLL-EEN relocate EBP. (A-C) Subcellular localization of Myc-tagged EBP 1-767, EBP 1-358, and EBP 532-767. (D) EEN and EBP colocalize in the cytoplasm. (E) NLSEEN interacts with and recruits EBP from the cytoplasm into the nucleus. (F) NLSEENΔSH3 mutant unable to relocate EBP into the nucleus. (G) MLL-EEN partially relocates EBP into the nucleus. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with Myc-tagged EBP with FLAG-tagged EEN or MLL-EEN. EBP and EEN/MLL-EEN were visualized by anti-Myc and anti-FLAG antibodies, followed by FITC-conjugated antirabbit and rhodamine-conjugated antimouse antibodies, respectively. Nucleus in each case was visualized by DAPI staining. Overlay of DAPI-, FITC-, and rhodamine-stained images are shown in the last column. Original magnification, × 1000.

Expression of EEN and MLL-EEN relocate EBP. (A-C) Subcellular localization of Myc-tagged EBP 1-767, EBP 1-358, and EBP 532-767. (D) EEN and EBP colocalize in the cytoplasm. (E) NLSEEN interacts with and recruits EBP from the cytoplasm into the nucleus. (F) NLSEENΔSH3 mutant unable to relocate EBP into the nucleus. (G) MLL-EEN partially relocates EBP into the nucleus. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with Myc-tagged EBP with FLAG-tagged EEN or MLL-EEN. EBP and EEN/MLL-EEN were visualized by anti-Myc and anti-FLAG antibodies, followed by FITC-conjugated antirabbit and rhodamine-conjugated antimouse antibodies, respectively. Nucleus in each case was visualized by DAPI staining. Overlay of DAPI-, FITC-, and rhodamine-stained images are shown in the last column. Original magnification, × 1000.

To determine whether EBP and EEN share similar subcellular localization, Myc-tagged EBP was expressed either alone or together with FLAG-tagged EEN in HeLa cells. Simultaneous ectopic expression of EBP and EEN in transfected cells displayed uniform cytoplasmic localization (Figure 5D). To test whether EBP and EEN could interact with each other, a nuclear localization signal (NLS) was added to EEN that would redirect EEN from the cytoplasm into the nucleus. HeLa cells transfected with Myc-tagged EBP and FLAG-tagged NLSEEN resulted in nuclear localization of both proteins (Figure 5E). In addition, NLSEEN with a deletion in SH3 domain, the EBP-binding domain, was unable to bring EBP into the nucleus (Figure 5F). This observation supports direct physical interaction between EBP and EEN in HeLa cells as well as a role of the SH3 domain of EEN in interacting and modulating the subcellular localization of EBP.

MLL-EEN fusion protein delocalizes EBP into the nucleus

The native nuclear localization of the MLL-EEN fusion gene prompts us to study the effect of coexpression of EBP and MLL-EEN in cells. In HeLa cells expressing exogenously introduced EBP and MLL-EEN, EBP is localized in both cytoplasm and nucleus (Figure 5G). MLL-EEN and EBP both exhibited a punctate localization in the nucleus, a pattern also reported for other MLL fusion proteins.32 Our study shows that MLL-EEN could only partially relocate EBP into the nucleus while NLSEEN could more efficiently relocate EBP into the nucleus. The difference in the ability of MLL-EEN and EEN in relocating EBP may be due to the significant protein size difference between the 2 proteins. We postulate that the relatively large protein size of MLL-EEN (1715 amino acids) as compared with EEN (368 amino acids) might prevent access of the EBP-binding domain in EEN to EBP. Under this circumstance, MLL-EEN would not be able to interact with all EBP proteins present inside the cells and relocate them all from the cytoplasm into the nucleus. Our results demonstrate that EEN specifically interacts with EBP, and its subcellular localization as an MLL-EEN fusion protein can directly affect the subcellular localization of EBP.

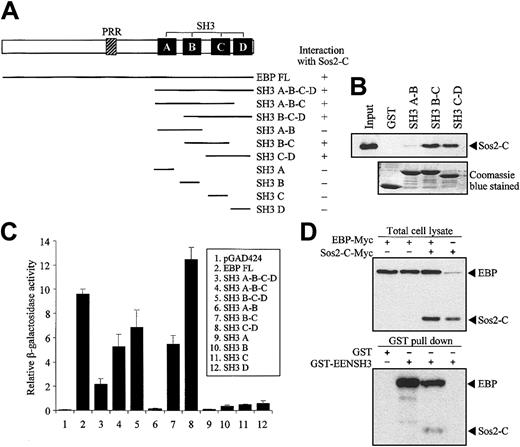

EBP interacts with EEN and Sos2 simultaneously

Structural comparison of EBP with known proteins revealed that EBP is similar to intersectin, an endocytic protein with multiple SH3 domains in the C-terminal.35,36 Moreover, Son of sevenless (Sos), a guanine-nucleotide exchange factor of Ras, was identified as an SH3 domain-binding partner of intersectin.37,38 To study the potential interaction between EBP and Sos, we performed yeast 2-hybrid cotransformation assays to test the interaction between deletion mutants of EBP fused to Gal4-BD and the C-terminal of Sos1 and Sos2 (Sos1-C and Sos2-C) fused to Gal4-AD. EBP was found to interact with Sos2 but not with Sos1 (data not shown). Our results showed that 2 pairs of the consecutive SH3 domains (SH3 B-C and SH3 C-D) of EBP were sufficient to interact with Sos2 (Figure 6A). The specific interactions between EBP SH3 domains and Sos2 were also demonstrated by the in vitro GST pull-down assay. In this assay, the first 2 SH3 domains of EBP (SH3 A-B) were unable to pull-down Sos2, while SH3 B-C and SH3 C-D could efficiently bind Sos2 (Figure 6B). By using quantitative liquid culture assay of the yeast cotransformants, the last 2 SH3 domains (SH3 C-D) had the highest binding affinity to Sos2 (Figure 6C).

EBP interacts with EEN and Sos2 simultaneously. (A) Yeast transformation assay of EBP with Sos2. Schematic diagram of deletion constructs of EBP is presented. Deletion mutants of EBP cloned in Gal4-BD plasmid were each cotransformed with Sos2 Gal4 DNA-AD into yeast strain SFY526. Positive interaction accessed by colony lift filter assay is indicated by +. (B) GST pull-down assay. Extract of HeLa cells expressing Myc-tagged Sos2-C was incubated with GST or GST-EBP SH3 domains (SH3 A-B, B-C, or C-D) immobilized on glutathione beads. Binding protein was detected with anti-Myc antibody. (C) Quantitative assay for EBP-EEN interaction. Transformants of Gal4-BD and Gal4-AD fusion pairs were assayed using ONPG substrate. Relative β-galactosidase activity was expressed as arbitrary units. Error bars represent ± SD. (D) Simultaneous interaction of EBP with Sos2 and EEN in HeLa cells. Expressions of EBP and Sos2-C in lysates of HeLa cells transfected with different combinations of Myc-tagged EBP and Sos2-C were confirmed in the upper panel. GST pull-down assay was shown in the lower panel using the HeLa cell lysates shown in the corresponding upper panel. HeLa cell lysates were incubated with GST or GST-EENSH3 fusion protein immobilized on glutathione beads. Bound proteins were detected by anti-Myc antibody.

EBP interacts with EEN and Sos2 simultaneously. (A) Yeast transformation assay of EBP with Sos2. Schematic diagram of deletion constructs of EBP is presented. Deletion mutants of EBP cloned in Gal4-BD plasmid were each cotransformed with Sos2 Gal4 DNA-AD into yeast strain SFY526. Positive interaction accessed by colony lift filter assay is indicated by +. (B) GST pull-down assay. Extract of HeLa cells expressing Myc-tagged Sos2-C was incubated with GST or GST-EBP SH3 domains (SH3 A-B, B-C, or C-D) immobilized on glutathione beads. Binding protein was detected with anti-Myc antibody. (C) Quantitative assay for EBP-EEN interaction. Transformants of Gal4-BD and Gal4-AD fusion pairs were assayed using ONPG substrate. Relative β-galactosidase activity was expressed as arbitrary units. Error bars represent ± SD. (D) Simultaneous interaction of EBP with Sos2 and EEN in HeLa cells. Expressions of EBP and Sos2-C in lysates of HeLa cells transfected with different combinations of Myc-tagged EBP and Sos2-C were confirmed in the upper panel. GST pull-down assay was shown in the lower panel using the HeLa cell lysates shown in the corresponding upper panel. HeLa cell lysates were incubated with GST or GST-EENSH3 fusion protein immobilized on glutathione beads. Bound proteins were detected by anti-Myc antibody.

Our results show that EBP has distinct binding sites for EEN and Sos2, and EEN and Sos2 do not interact with each other (data not shown). To address the question of whether EBP is able to interact with EEN and Sos simultaneously and form a stable trimeric protein complex, we performed a coimmnuoprecipitation reaction followed by a GST pull-down assay. Myc-tagged EBP and Sos2-C were transfected into HeLa cells and incubated with GST-EENSH3 fusion protein immobilized on glutathione sepharose beads. Both Myc-tagged proteins could be differentiated by their significant protein size difference. EBP-Myc protein could be pulled down by GST-EENSH3, and Sos2-C-Myc could only be detected when EBP-Myc was cotransfected (Figure 6D).

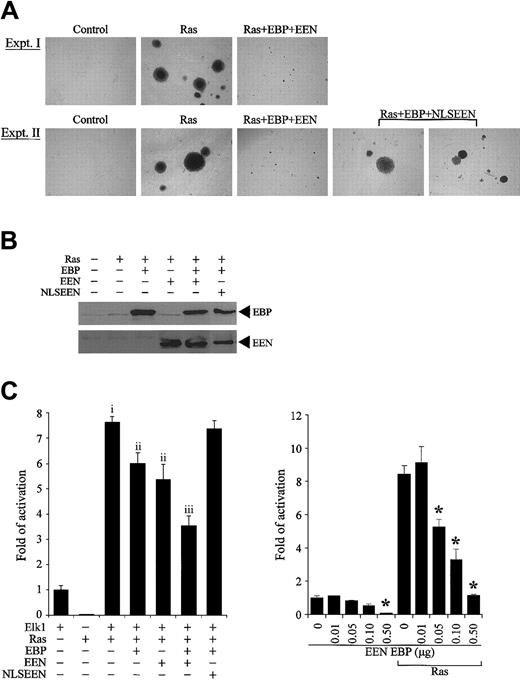

Expression of EBP and EEN inhibits Ras transformation potential and Ras-mediated activation of Elk-1

Association of EBP with Sos2, a guanine exchange factor of Ras, prompted us to investigate the effect of EBP and EEN on Ras-induced cellular transformation. Stable transfectants of R6 cells expressing dominant active mutant RasQ61L with or without EBP and/or EEN or NLSEEN were examined for anchorage-independent growth on soft agar. While normal R6 cells remained as single cells, R6 cells expressing RasQ61L formed a significant number of large colonies (P < .001, ANOVA) (Figure 7A-B). Cotransfection with either EBP or EEN decreased the number and size of colonies by more than 30% and 60%, respectively (P < .001, ANOVA) (Table 3, experiment I). Reduction in transformation potential was further enhanced when cells were transfected with both EBP and EEN (P < .05, ANOVA). This inhibitory effect was dramatically reduced when EBP was transfected with NLSEEN (Table 3, experiment II). Cells transfected by Ras with EBP and NLSEEN formed large colonies comparable to Ras-transformed cells (Figure 7A) and formed 60% more colonies than RasQ61L-, EBP-, and EEN-transfected cells (P < .001, ANOVA) (Figure 7B, experiment II). The expressions of EBP and EEN in stable transfectants were detected by Western blot analysis (Figure 7B).

EBP and EEN inhibit the transformation potential of Ras and Ras-mediated activation of Elk-1. (A) Representative colonies of soft agar assays. Ras+EBP+EEN formed small colonies (experiment I), while Ras+EBP+NLSEEN formed large colonies similar to Ras-transformed cells (experiment II). (B) Expression of exogenous EBP-Myc, EEN-FLAG, and NLSEEN-FLAG proteins in stably transfected R6 cells was confirmed by Western blot analysis. (C) EBP and EEN inhibit Ras-mediated activation of Elk-1. RasQ61L-induced activation of Elk-1 (vector control and f; P < .001, ANOVA). Either EBP or EEN alone reduces Elk-1 activation (i and ii; P < .001, ANOVA). The inhibition is further enhanced with both EBP and EEN (ii and iii; P < .001, ANOVA). (D) Dosage-dependent inhibition of EBP and EEN on the Elk-1 transactivation by Ras. Asterisk indicates the concentrations under which significant inhibition on Elk-1 transactivation was observed (P < .05, ANOVA). Error bars represent SDs of triplicate transfections of 2 independent experiments.

EBP and EEN inhibit the transformation potential of Ras and Ras-mediated activation of Elk-1. (A) Representative colonies of soft agar assays. Ras+EBP+EEN formed small colonies (experiment I), while Ras+EBP+NLSEEN formed large colonies similar to Ras-transformed cells (experiment II). (B) Expression of exogenous EBP-Myc, EEN-FLAG, and NLSEEN-FLAG proteins in stably transfected R6 cells was confirmed by Western blot analysis. (C) EBP and EEN inhibit Ras-mediated activation of Elk-1. RasQ61L-induced activation of Elk-1 (vector control and f; P < .001, ANOVA). Either EBP or EEN alone reduces Elk-1 activation (i and ii; P < .001, ANOVA). The inhibition is further enhanced with both EBP and EEN (ii and iii; P < .001, ANOVA). (D) Dosage-dependent inhibition of EBP and EEN on the Elk-1 transactivation by Ras. Asterisk indicates the concentrations under which significant inhibition on Elk-1 transactivation was observed (P < .05, ANOVA). Error bars represent SDs of triplicate transfections of 2 independent experiments.

Numeric data of the size and number of colonies

. | Experiment I . | . | Experiment II . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | No. of colonies . | Size range, mm in diameter . | No. of colonies . | Size range, mm in diameter . | ||

| Vector control | 5 ± 1 | 0.05-0.07 | 4 ± 3 | 0.05-0.08 | ||

| RasQ61L | 516 ± 25* | 0.05-0.68 | 604 ± 31* | 0.05-0.72 | ||

| RasQ61L + EBP | 348 ± 23†,† | 0.05-0.27 | ND | ND | ||

| RasQ61L + EEN | 330 ± 26†,† | 0.05-0.24 | ND | ND | ||

| RasQ61L + EBP + EEN | 289 ± 20‡,‡ | 0.05-0.21 | 250 ± 23§,§ | 0.05-0.15 | ||

| RasQ61L + EBP + NLSEEN | ND | ND | 416 ± 11∥∥ | 0.05-0.70 | ||

. | Experiment I . | . | Experiment II . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | No. of colonies . | Size range, mm in diameter . | No. of colonies . | Size range, mm in diameter . | ||

| Vector control | 5 ± 1 | 0.05-0.07 | 4 ± 3 | 0.05-0.08 | ||

| RasQ61L | 516 ± 25* | 0.05-0.68 | 604 ± 31* | 0.05-0.72 | ||

| RasQ61L + EBP | 348 ± 23†,† | 0.05-0.27 | ND | ND | ||

| RasQ61L + EEN | 330 ± 26†,† | 0.05-0.24 | ND | ND | ||

| RasQ61L + EBP + EEN | 289 ± 20‡,‡ | 0.05-0.21 | 250 ± 23§,§ | 0.05-0.15 | ||

| RasQ61L + EBP + NLSEEN | ND | ND | 416 ± 11∥∥ | 0.05-0.70 | ||

ND indicates not determined

Vector control and *: P < .001, ANOVA.

and †, ‡, §, ∥: P < .001, ANOVA.

and ‡, § and ∥: P < .05, ANOVA.

Because EBP displays high structural similarity with the multiple SH3 domains in the C-terminal of intersectin, which has been reported to interact with Sos and activate Elk-1 activation,39,40 we also investigated the effect of EBP on the downstream signaling of Ras by performing luciferase assay using Gal4-Elk-1 transreporter. Expression of RasQ61L, a constitutively active mutant, enhanced the activation of Elk-1 transreporter by 6-fold (P < .001, ANOVA) (Figure 7C). When either EBP or EEN was cotransfected with RasQ61L, activation of Elk-1 transcription factor by RasQ61L was reduced by 20% (P < .001, ANOVA). The effect of inhibition by EBP and EEN was further enhanced by 30% and was more efficient than expression of either EBP or EEN alone (P < .001, ANOVA). However, this inhibitory effect was lost when NLSEEN and EBP were cotransfected, and more than 96% of the promoter activity was retained. Because NLSEEN interacts and relocates EBP into the nucleus (Figure 5E), the results of our reporter assays suggest that the inhibitory effect of EEN and EBP on activation of Elk-1 requires the cytoplasmic localization of both EEN and EBP. The inhibition effect of EBP and EEN on the basal activity and Ras-mediated activation of Elk-1 occurred in a dose-dependent manner (P < .05, ANOVA) (Figure 7D). Taken together, our results show that EBP and EEN cooperatively inhibit Ras signaling and also suppress cellular transformation induced by Ras. Based on our previous attempts and observations reported by other groups, stable expression of MLL-EEN could not be achieved in cell lines. In our study, to mimic the situation that EBP is delocalized into the nucleus by MLL-EEN, we instead used NLSEEN, which can bring EBP into the nucleus and can be stably expressed. At present, we can observe the effect of bringing EBP from the cytoplasm into the nucleus by NLSEEN. The inhibition of Ras-induced transformation and Elk-1 activation is lost with NLSEEN when compared with EEN. Based on unpublished observations (C.W.S., 2002), MLL-EEN can be expressed in primary hematopoietic cells; thus, the effect of MLL-EEN on Ras signaling will be addressed in the future by using primary hematopoietic cells.

Discussion

EEN was originally identified as an MLL fusion partner22 in acute myeloid leukemia and is required for transformation of murine myeloid progenitors by MLL-EEN fusion (C.W.S., unpublished observations, 2003). To investigate the role of EEN in the pathogenesis of leukemia, we have identified and characterized a ubiquitously expressed protein, EBP, as a novel binding partner of EEN. Structurally, EBP comprises an N-terminal region, a central proline-rich region, followed by 4 SH3 domains in the C-terminal. Fine mapping of EBP reveals a proline-rich binding motif, PPERP (residues 343-347), which interacts with the SH3 domain of EEN and is consistent with the consensus endophilin binding sequence, PPXRP.34 Specific and direct interaction between EBP and EEN was further confirmed by the in vitro GST pull-down assay and in vivo coimmunoprecipitation studies (Figure 4). In spite of the high sequence homology of the SH3 domains among the EEN family members, the preferential interaction between EEN and EBP (Figure 3) further strengthens the notion that EBP is a bona fide interacting partner for EEN, and each EEN member may have related but distinct functional roles in cell signaling.

Structural and functional analysis shows that EBP shares some similarity to intersectin, an adaptor protein with multiple SH3 domains that interacts with Sos, a guanine-nucleotide exchange factor and activator of Ras.38 Analogous to intersectin, EBP recruits Sos2 via its SH3 domains to form a stable trimeric complex with EEN mediated by its consensus endophilin binding sequence. Intersectin has been shown to regulate the Ras/mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathway and activate Elk-1 transcription factor, resulting in oncogenic transformation of rodent cells.38-40 Overexpression of a dominant negative mutant with SH3 domains of intersectin repressed the activation of Ras and Elk-139 and failed to induce transformation.40 In contrast to intersectin, the expression of EBP not only suppressed the transcriptional activation of Elk-1 but also Ras-induced oncogenic transformation (Figure 7). Moreover, coexpression of EEN significantly enhanced the inhibitory effects on Ras-mediated transactivation and transformation (Figure 7), suggesting that the EEN-EBP-Sos trimeric complex likely contributes to the observed repressive effects. Taken together, these results indicate that EBP acts as an adaptor module in the EEN-EBP-Sos2 complex and that it cooperates with EEN to inhibit the Ras-stimulating activity of Sos2. In this context, EBP and EEN could be viewed to possess tumor suppressor properties in the negative feedback control of Ras-mediated signaling and cellular transformation.

To investigate the potential effect of MLL-EEN fusion on this trimeric complex, we also demonstrated that MLL-EEN oncoprotein displayed punctate nuclear localization pattern (Figure 5), which accords with several studies showing that the N-terminus of MLL is responsible for targeting fusion protein into the nucleus where it exerts its oncogenic potential.31 Interestingly, EBP is relocated from cytoplasm into the nucleus and displayed similar punctate nuclear localization pattern by MLL-EEN oncoprotein. These results strongly indicate that MLL-EEN fusion not only has a dosage but also a dominant negative effect on the native EEN and EBP proteins, which inhibit Sos2 and Ras signaling. We speculate that this subversion of the tumor-suppressing activities of EEN and EBP could contribute to constitutive Ras activation and cellular transformation.

There is growing evidence that interaction of the Ras signaling pathway may be a common biologic phenomenon for several MLL fusion partners. Both Sos1 and Sos2 were also identified as the binding partners for Abl interactor 1 (Abi-1), another MLL cytoplasmic fusion partner that shares structural similarity with EEN.41 E3b1/Abi-1 was originally isolated as the binding protein of Eps8, an SH3 domain–containing protein that plays a role in mitogenic signaling.42,43 Abi-1 and Sos1 form a trimeric complex with Eps8 that mediates transduction of signals from Ras to Rac44 and is required for the inhibition of growth factor– and v-Abl–mediated activation of Erk.45 MLL fusion proteins including the AF4 family and AF6 are also involved in Ras signaling,46-48 and N-ras and K-ras mutation have been reported for leukemia patients with t(11; 17)(q23; q25) and other MLL translocations.49,50 The pathologic significance of the Ras-mediated pathways in MLL leukemogenesis is further strengthened by the identification of EEN SH3 domain as a critical transformation domain, which is sufficient for MLL-EEN–mediated myeloid transformation (C.W.S. et al, unpublished observations, 2003). Although gain of function on MLL-dependent pathways is likely the most critical primary or initiating event in the multigenetic program of MLL fusion–mediated leukemogenesis, we present evidence to suggest that deregulation of Ras signaling pathways by either MLL fusion proteins or cooperative secondary mutations might represent one of the key secondary events required for establishment of the full leukemic phenotype.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, October 9, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2452.

Supported by grants from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (Project no. HKU7252/99M). D.-Y.J. is a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Scholar, and C.W.S. is a special fellow of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Cary So and Michael Cheung for technical assistance and Kevin Chew for graphical presentation. We also acknowledge Professor Stephen P. Goff for generously providing the Sos1 and Sos2 plasmids and Dr Wendy W. L. Hsiao for providing the R6 cell line.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal