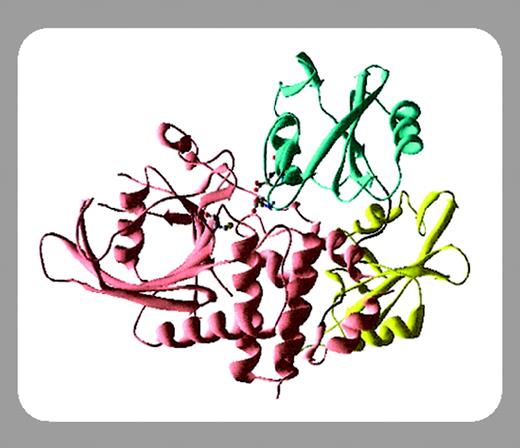

SHP-2 is a cytoplasmic tyrosine phosphatase with 2 src homology 2 (SH2) domains that was identified about 10 years ago and, most interestingly, acts to promote signal relay through the Ras-Erk pathway that plays a central role in cell proliferation and differentiation.1,2 Although it remains unclear how a phosphatase is positively required for promotion of the Ras pathway, this notion was strikingly illustrated by identification of germline mutations in PTPN11, the gene coding for SHP-2, in patients with Noonan syndrome (NS) with cardiac and skeletal defects.3 The autosomal dominant mutations identified cause amino acid substitutions that apparently disrupt an autoinhibitory interaction of the N-terminal of SH2 (SH2-N) domain with the PTPase domain, leading to expression of an excessively active phosphatase. More recently, somatic PTPN11 mutations of a similar pattern were detected in patients with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML) as well as in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia (AML).4 In this issue of Blood, Loh and colleagues (page 2325) report an independent identification of somatic mutations in the SH2-N domain of SHP-2 in JMML specimens. Similar to those identified in patients with NS, the somatic mutations found in patients with JMML are clustered on the SH2-N and PTPase interaction surface, with D61Y and E76K most frequently detected. Furthermore, both groups found that mutations in PTPN11, RAS, and NF1 are mutually exclusive in JMML. Together, these results identify SHP-2 as a first oncogenic tyrosine phosphatase in myeloid leukemias and suggest that the mutant SHP-2 molecule apparently promotes malignant cell proliferation by deregulating the Ras and possibly other signaling pathways. Preliminary functional analysis data suggest that the expression of mutant SHP-2 may or may not directly influence the Erk activation status. Clearly, more work is needed to fully understand the molecular mechanisms.

Somatically acquired mutations have also been detected in a number of genes coding for transcription factors.5 In this issue of Blood, Harada and colleagues (page 2316) report identification of a new type of mutation in the AML1/RUNX1 gene in patients with MDS and patients with AML. Previous publications by this group and others demonstrated somatic mutations in AML1/RUNX1 that were localized to the N-terminal region, particularly in the DNA-binding Runt homology domain (RHD). The present study extended the previous work of the investigators by detecting frame-shift mutations in the C-terminal part of the transcription factor, mainly in patients with MDS with refractory anemia with excess blast (RAEB), RAEB in transformation (RAEBt), and AML following MDS. Functional analysis using a gene-reporter assay demonstrated that all the C-terminal mutations abolished its trans-activation capacity and thus that these mutants could be viewed as dominant-negative suppressors of wild-type AML1 protein.

In sum, mechanisms have been used in leukemogenesis that alter the cell regulation machinery either in cytoplasmic signaling pathways or in control of gene expression in the nucleus. Significantly, the work on SHP-2 by Harada and colleagues as well as by Tartaglia and colleagues3,4 adds a tyrosine phosphatase to the list of potential oncoproteins and strongly supports the notion that SHP-2 is a positive regulator of the Ras pathway. Mechanistic studies of these leukemic cells in vitro or in vivo by creating appropriate transgenic animal models will certainly provide fundamental insights into myeloid malignancy, thereby offering novel and more effective therapeutic strategies for patients with leukemia. Identification of these natural mutants will also facilitate the basic research aimed at elucidating the molecular mechanisms for cytoplasmic signaling and gene expression in normal hematopoiesis.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal