Abstract

The monocyte capacity to differentiate into dendritic cells (DCs) was originally demonstrated by human in vitro DC differentiation assays that have subsequently become the essential methodologic approach for the production of DCs to be used in DC-mediated cancer immunotherapy protocols. In addition, in vitro DC generation from monocytes is a powerful tool to study DC differentiation and maturation. However, whether DC differentiation from monocytes occurs in vivo remains controversial, and the physiologic counterparts of in vitro monocyte-derived DCs are unknown. In addition, information on murine monocytes and monocyte-derived DCs is scarce. Here we show that mouse bone marrow monocytes can be differentiated in vitro into DCs using similar conditions as those defined in humans, including in vitro cultures with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin 4 and reverse transendothelial migration assays. Importantly, we demonstrate that after in vivo transfer monocytes generate CD8- and CD8+ DCs in the spleen, but differentiate into macrophages on migration to the thoracic cavity. In conclusion, we support the hypothesis that monocytes generate DCs not only on entry into the lymph and migration to the lymph nodes as proposed, but also on extravasation from blood and homing to the spleen, suggesting that monocytes represent immediate precursors of lymphoid organ DCs. (Blood. 2004;103:2668-2676)

Introduction

In vitro human dendritic cell (DC) derivation from monocytes has proven to be an extremely powerful tool for the study of the processes of DC differentiation and maturation and constitutes the current methodologic basis of ongoing DC-mediated cancer immunotherapies.1 However, whether DC differentiation from monocytes occurs under physiologic situations has not been conclusively demonstrated and remains a controversial issue in DC biology. In addition, the putative in vivo counterparts of in vitro monocyte-derived DCs have not been defined yet. In this sense, in an attempt to define the physiologic conditions controlling DC derivation from monocytes, using an in vitro culture system, Randolph et al2 have shown that human monocytes differentiate into DCs on uptake of zymosan and reverse transendothelial migration. Surprisingly, the available information on the mechanism of DC differentiation from monocytes in the murine system is very limited, despite the fact that this problem could potentially be addressed in mice by using powerful experimental models not applicable in humans, which could contribute significantly to our understanding of this process.

On the other hand, to our knowledge the issue of DC derivation from monocytes in mice has only been addressed in 2 reports. Schreurs et al have described the generation of DCs in vitro in the presence of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and interleukin 4 (IL-4) from nondefined blood adherent cells, considered as monocytes.3 Randolph et al4 have reported the in vivo differentiation of dermal phagocytes, claimed to correspond to extravasated monocytes, into DCs on uptake of latex particles and migration into the draining lymph nodes. In these articles monocytes were neither characterized nor isolated, and the possible correlation between monocyte-derived DCs and the different DC subsets described in vivo was not addressed. Concerning this point, the data derived from the 2 reports from Randolph et al2,4 support the concept that monocyte differentiation into DCs occurs on reverse transendothelial migration to the lymphatics and homing to the lymph nodes.

To address the DC differentiation potential of monocytes in mice, a phenotypic analysis of mouse monocytes has been achieved, which has allowed the design of an efficient monocyte isolation protocol, required to perform the subsequent DC differentiation assays considered in this report, that included in vitro cultures in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4, in vitro reverse transendothelial migration experiments, as well as in vivo DC reconstitution assays. Our data demonstrate that 24 hours after culture under the in vitro conditions previously defined in the human system, mouse monocytes could differentiate into DCs by a process not involving cell proliferation. More important, we demonstrate that DC derivation from monocytes occurred in vivo and led to the generation of both CD8α- and CD8α+ splenic DCs, as reported for CD11c+ major histocompatibility complex (MHC) II- DC precursors, recently described in our laboratory.5 In conclusion, our data support the hypothesis that monocytes can generate DCs not only on reverse transendothelial migration to the lymphatics and homing to the lymph nodes as previously proposed, but also on extravasation from the bloodstream and homing to the spleen, and suggest that monocytes represent immediate precursors of DCs located in peripheral lymphoid organs.

Materials and methods

Mice

For phenotypic and functional experiments 5- to 6-week-old C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice were used. In reconstitution experiments, donors were C57 BL/Ka Ly 5.2 mice and recipients were 8-week-old C57BL/6 Ly 5.1 Pep3b mice.

Monocyte isolation

Monocytes were isolated from lysis buffer-treated heparinized blood or bone marrow by immunomagnetic bead depletion with antirat immunoglobulin-coated magnetic beads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) at a 7:1 bead-to-cell ratio, after incubation with monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) anti-CD3, CD4, CD8α, MHC class II (MHC II), B220, CD43, and CD24 (heat-stable antigen [HSA]). After immunomagnetic bead depletion, monocyte preparations had a purity of more than 95%. For monocyte transfer experiments, highly purified monocyte preparations with a purity of more than 98% were then obtained by magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS; Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch, Germany) after incubation with biotin-conjugated anti-Ly-6C and streptavidin-conjugated MACS microbeads. All the functional assays were performed with bone marrow monocytes.

In vitro differentiation of DCs from monocytes

Purified bone marrow monocytes were cultured at 1 × 106 cells/mL in 24-well plates in the absence or presence 20 ng/mL GM-CSF (Peprotech, London, United Kingdom) and IL-4 (Peprotech), or 20 ng/mL macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF; Peprotech). Culture medium was RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME), and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin. In some experiments cultures were treated for additional 24 hours with 1 μg/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli (Sigma, St Louis, MO) to induce DC or macrophage activation. Inhibition of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) was achieved by treatment with the PI3K inhibitor Ly 294002 (Sigma) at 25 μM for 4 hours. Monocyte proliferation in cultures with GM-CSF and IL-4 was assessed after labeling with the intracellular fluorescent dye carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands) at 1 μM for 10 minutes at 37°C.

Mixed lymphocyte reaction assay

Nonirradiated LPS-treated or untreated DCs from day-3 cultures of bone marrow monocytes with GM-CSF and IL-4, LPS-treated or untreated macrophages from day-3 cultures of monocytes with M-CSF, uncultured bone marrow monocytes, or splenic DCs from C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice were cultured with mesenteric lymph node T cells from BALB/c (H-2d) mice, in flat-bottom 96-well plates (1 × 105 cells/well), at different antigen-presenting cell/T-cell (APC/T-cell) ratios. T-cell proliferation was assessed after 4 days by [3H]-thymidine (1 μCi/well [0.037 MBq/well]) uptake in a 12-hour pulse.

Reverse transendothelial migration assay

Reverse transendothelial migration experiments were performed using a method modified from Randolph et al.2 Human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs) were grown on endotoxin-free type I collagen gels (Cellagen; ICN Biomedicals, Aurora, OH) in 24-well plates (Costar, Corning, NY), and cultured in Medium 199 (Gibco, Life Technologies, Paisley, United Kingdom) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS). In some experiments collagen gels were mixed with 0.0025% zymosan (Sigma). Purified bone marrow monocytes were incubated for 16 hours over confluent endothelial monolayers grown on type I collagen gel, in the presence or absence of zymosan, to allow their migration across the endothelial layer into the collagen gel, and then washed to remove nonmigrated cells. After 48 hours, reverse-transmigrated cells were harvested from the culture medium and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Monocyte transfer experiments

A total of 0.5 to 2 × 106 highly purified (> 98% purity) bone marrow monocytes from C57 BL/Ka Ly 5.2 donor mice were injected intravenously into γ-irradiated (7 Gy) C57 BL/6 Ly5.1 Pep3b recipient mice, along with 4 × 104 Ly5.1 bone marrow cells to ensure survival of recipients. Donor-type cells were analyzed on splenic DC-enriched low-density cell fractions obtained as previously described,6 tail vein blood, thoracic cavity, and peritoneal lavage specimens.

Flow cytometry

Monocytes were analyzed by flow cytometry in lysis buffer-treated samples of bone marrow or heparinized blood depleted of B cells with antimouse immunoglobulin-coated magnetic beads (Dynal). Characterization of monocytes was achieved after double staining with either fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD11b (Mac-1, clone M1/70) and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-Gr-1 (Ly-6G, clone RB6-8C5; Caltag, Burlingame, CA), or FITC-conjugated antimacrophage antigen F4/80 (clone 32-A3-1) and PE-conjugated anti-Gr-1, or FITC-conjugated anti-CD11b and PE-conjugated anti-Ly-6C (clone HK1.4; Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL). Phenotypic analysis of monocytes was performed after triple staining with FITC-conjugated anti-CD11b and PE-conjugated anti-Ly-6C and biotin-conjugated anti-FcγRII/III (CD16 and CD32, clone 2.4G2), anti-CD11c (clone N418), anti-MHC II (clone FD11-54.3), anti-DEC205 (CD205, clone NLDC-145), anti-CD40 (clone FGK45), anti-CD86 (B7-2, clone GL1; PharMingen), anti-CD43 (clone S7), anti-CD24 (HSA, clone M1/69), anti-CD44 (clone IM7.81), anti-CD62L (clone Mel-14), anti-CD69 (clone H.1.2F3), anti-B220 (clone RA3-6B2), anti-IL-3Rα (CD123, clone 5B11; PharMingen), anti-CD4 (clone GK1.5), anti-CD8α (clone 53-6.72), anti-CD90 (Thy-1, clone AT15), followed by streptavidin-tricolor (Caltag). Phenotypic analysis of cultured monocytes was performed after triple staining with FITC-conjugated anti-MHC II, PE-conjugated anti-CD11c (clone HL3; PharMingen), and biotin-conjugated anti-CD86, anti-CD40, anti-CD69, anti-F4/80, anti-Ly-6C, anti-CD8α, anti-B220, anti-CD11b, or anti-CD62L followed by streptavidin-tricolor. Phenotype of transmigrated cells in reverse transmigration experiments was analyzed after triple staining with FITC-conjugated anti-MHC II, PE-conjugated anti-CD11c, and biotin-conjugated anti-CD45 (clone M1/89) followed by streptavidin-tricolor or FITC-conjugated anti-F4/80, PE-conjugated anti-Ly-6C, and biotin conjugated anti-CD45 followed by streptavidin-tricolor, after gating out endothelial cells on the basis of their null CD45 expression level. Analysis of monocyte differentiation after transfer into irradiated recipients was performed on splenic DC-enriched low-density cell fractions, heparinized tail vein blood, and thoracic and peritoneal cavity lavage specimens after triple staining with FITC-conjugated anti-Ly-5.2 (clone ALI-4A2; PharMingen), PE-conjugated anti-CD11c, or anti-Ly-6C and biotin-conjugated anti-MHC II, anti-CD8α, or antimacrophage antigen F4/80, followed by streptavidin-tricolor. Fc receptors were blocked with purified rat immunoglobulins and with the anti-FcγRII/III mAb 2.4G2 (not included for FcR expression analysis). Analysis was performed on a FACSort flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA).

Reverse transcription-PCR analysis of TLR-4 and TLR-9 expression

mRNA was purified from FACS-sorted cells using magnetic beads (mRNA direct micro kit; Dynal), reverse transcribed, and subjected to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification using the following primers: Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) forward, CTA GGA CTC TGA TCA TGG CAC; TLR- 4 reverse, CAG CCA CCA GAT TCT CTA AAC; TLR-9 forward, AAC ATG GTT CTC CGT CGA AGG; TLR-9 reverse, GTA GTA GCA GTT CCC GTC C. PCR conditions were 15 seconds at 94°C, 30 seconds at 51°C, and 60 seconds at 72°C. PCR products were TLR-4, 375 base pair (bp), and TLR-9, 543 bp. PCR was performed on a GeneAmp PCR System 9700, using 1.25 UAmpliTaq gold polymerase per PCR (Perkin Elmer, Foster City, CA). PCR products were analyzed on agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide and photographed with a Nikon Coolpix 950 digital camera (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Light and phase-contrast microscopy

Cytospin slides of cell suspensions from uncultured bone marrow monocytes or cultured for 3 days with GM-CSF plus IL-4 or M-CSF, in the absence or presence of LPS, were analyzed using a phase-contrast Leica DMLB microscope equipped with a Nikon Coolpix 990 digital camera (Nikon). In addition, some slides were processed for the detection of nonspecific esterase (NSE) activity using α-naphthyl acetate and pararosaniline (both from Sigma) as substrate and coupling agent, respectively.

Results

Characterization of blood and bone marrow monocytes

To study the derivation of DCs from monocytes in the murine system, a phenotypic characterization of mouse monocytes has been performed because, despite several reports dealing with the functional properties of monocytes in the mouse, a precise definition of their phenotype was lacking. As we describe, these results have also allowed the design of an efficient monocyte isolation method from blood or bone marrow.

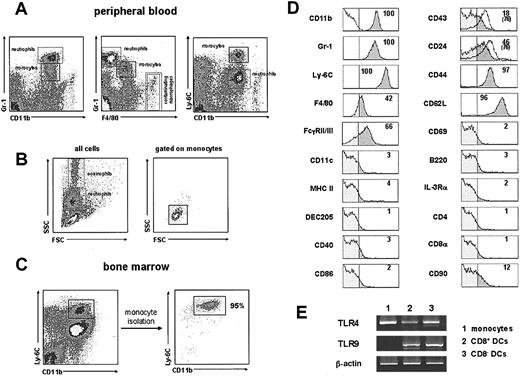

Monocytes were initially identified by flow cytometry in B cell-depleted peripheral blood preparations on the basis of their CD11b versus Gr-1 expression pattern described by Lagasse and Weissman.7

As illustrated in Figure 1A, monocytes were defined by correlating their level of CD11b, Gr-1, F4/80, and Ly-6C expression, referred to that of neutrophils and macrophages, as CD11bint, Gr-1int, F4/80low, Ly-6Chigh cells. Interestingly, in a recent report Palframan et al8 have reported the existence of 2 different subsets of mouse circulating monocytes differing in F4/80 expression. However, because F4/80- monocytes constituted a minor monocyte population in our blood samples, they have not been considered in this study. Note that the few CD11bhigh F4/80high macrophages present in the dot plot panels of Figure 1A correspond to noncirculating macrophages from the thoracic cavity, contaminating blood samples that were obtained in these experiments by cardiac puncture. This was confirmed by analyzing the peripheral blood directly collected from the tail vein, where neither macrophages nor CD11c+ MHC IIhigh DCs could be detected, although CD11c+ MHC IIint plasmacytoid DCs were found (data not shown). The CD11b versus Ly-6C profile appeared to provide the best gating for monocytes and allowed to determine accurately their forward scatter (FSC) versus side scatter (SSC) profile (Figure 1B), their characterization in bone marrow (Figure 1C), as well as their phenotypic characterization (Figure 1D). Monocytes displayed slightly higher FSC and SSC than peripheral blood lymphocytes, similar FSC values to granulocytes, but notably lower SSC than the latter (Figure 1B).

Characterization and phenotype of mouse monocytes. (A) Monocytes were identified in lysis buffer-treated, B-cell-depleted, heparinized blood by correlating their expression of CD11b, Gr-1, F4/80, and Ly-6C. Monocytes and neutrophils are shown in the boxes with solid and dashed lines, respectively, to allow the comparison of their relative expression level of the indicated markers. Cells in the boxes with double dashed line correspond to noncirculating CD11bhigh F4/80high macrophages from the thoracic cavity. (B) FSC versus SSC profiles of ungated total blood cells (left), and after gating for monocytes on the basis of their CD11b versus Ly-6C expression (right). (C) CD11b versus Ly-6C profiles of total bone marrow samples and of purified bone marrow monocytes (see “Materials and methods” for details on monocyte purification). (D) Phenotypic analysis by flow cytometry of C57BL/6 mouse blood monocytes performed by triple immunofluorescent staining after gating on monocytes on the basis of their CD11b versus Ly-6C profile, as shown in panel A. The percentage of cells with a fluorescence intensity over the vertical lines (dark gray area of the profiles), corresponding to the upper limit of control background staining (shown in the CD11b histogram), is indicated. White profiles on the CD43 and CD24 histograms correspond to the expression of these markers by BALB/c blood monocytes (in these cases the percentage of cells with a fluorescence intensity over the background staining is indicated in parentheses). Data are representative of 5 experiments with similar results. (E) RT-PCR analysis of TLR-4 and TLR-9 expression by bone marrow monocytes. CD8+ and CD8- splenic DCs were used as positive controls for both TLR-4 and TLR-9 expression. β-Actin mRNA levels are shown to control for the relative expression of TLR-4 and TLR-9 mRNA in the different populations considered. Data are representative of 2 experiments with similar results.

Characterization and phenotype of mouse monocytes. (A) Monocytes were identified in lysis buffer-treated, B-cell-depleted, heparinized blood by correlating their expression of CD11b, Gr-1, F4/80, and Ly-6C. Monocytes and neutrophils are shown in the boxes with solid and dashed lines, respectively, to allow the comparison of their relative expression level of the indicated markers. Cells in the boxes with double dashed line correspond to noncirculating CD11bhigh F4/80high macrophages from the thoracic cavity. (B) FSC versus SSC profiles of ungated total blood cells (left), and after gating for monocytes on the basis of their CD11b versus Ly-6C expression (right). (C) CD11b versus Ly-6C profiles of total bone marrow samples and of purified bone marrow monocytes (see “Materials and methods” for details on monocyte purification). (D) Phenotypic analysis by flow cytometry of C57BL/6 mouse blood monocytes performed by triple immunofluorescent staining after gating on monocytes on the basis of their CD11b versus Ly-6C profile, as shown in panel A. The percentage of cells with a fluorescence intensity over the vertical lines (dark gray area of the profiles), corresponding to the upper limit of control background staining (shown in the CD11b histogram), is indicated. White profiles on the CD43 and CD24 histograms correspond to the expression of these markers by BALB/c blood monocytes (in these cases the percentage of cells with a fluorescence intensity over the background staining is indicated in parentheses). Data are representative of 5 experiments with similar results. (E) RT-PCR analysis of TLR-4 and TLR-9 expression by bone marrow monocytes. CD8+ and CD8- splenic DCs were used as positive controls for both TLR-4 and TLR-9 expression. β-Actin mRNA levels are shown to control for the relative expression of TLR-4 and TLR-9 mRNA in the different populations considered. Data are representative of 2 experiments with similar results.

Definition of the phenotypic characteristics of monocytes allowed the design of an isolation method for monocytes from peripheral blood or bone marrow, although in the functional assays considered in this report monocytes were isolated from bone marrow, due to the significantly higher yield obtained when using bone marrow compared to peripheral blood (up to 10 × 106 versus 0.2 × 106 monocytes per mouse after magnetic bead depletion). Monocyte preparations obtained by magnetic bead depletion of unwanted cells, as described in “Materials and methods,” had a purity higher than 95% (Figure 1C), and more than 98% after subsequent MACS of Ly-6C+ cells (not shown). Giemsa staining of purified monocytes performed on cytospin slides confirmed that they displayed a characteristic monocyte morphology, as well as the purity of the monocyte preparation (Figure 5). The efficiency of the isolation method was higher in C57BL/6 than in BALB/c mice because, as pointed out (Figure 1D), the significantly lower CD43 and CD24 levels displayed by monocytes in C57BL/6 mice compared to BALB/c, allowed the inclusion of antibodies against these molecules for the immunomagnetic depletion step during monocyte isolation from C57BL/6 mice, but not from BALB/c. For this purpose mAbs against CD43 and CD24 were titrated to define the adequate working concentration allowing the depletion of cells expressing intermediate and high levels of these 2 markers, without depleting monocytes. In this respect, it is important to consider that CD24 expression is significantly lower in monocytes than in the rest of bone marrow cells (not shown).

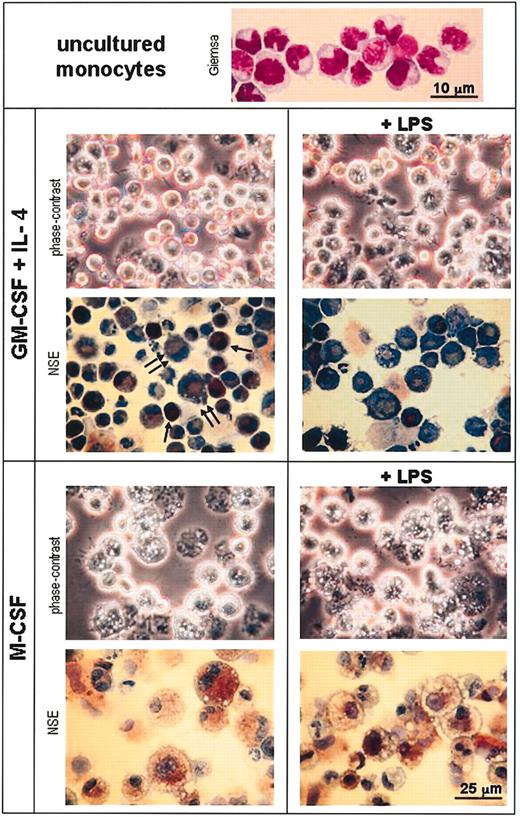

Morphologic analysis of monocytes and day-3 monocyte cultures with GM-CSF plus IL-4 or M-CSF. Cytospin slides from uncultured purified monocytes were stained with Giemsa (lens magnification, × 100; scale bar is 10 μm). Cytospin slides from day-3 cultures of monocytes with GM-CSF plus IL-4 or M-CSF in the absence or presence of LPS were analyzed unstained by phase-contrast microscopy or processed for the detection of NSE and counterstained with toluidine blue (final magnification, × 100; scale bar is 25 μm). Single and double arrows indicate strongly and weakly NSE-positive cells, respectively, corresponding to immature and mature DCs.

Morphologic analysis of monocytes and day-3 monocyte cultures with GM-CSF plus IL-4 or M-CSF. Cytospin slides from uncultured purified monocytes were stained with Giemsa (lens magnification, × 100; scale bar is 10 μm). Cytospin slides from day-3 cultures of monocytes with GM-CSF plus IL-4 or M-CSF in the absence or presence of LPS were analyzed unstained by phase-contrast microscopy or processed for the detection of NSE and counterstained with toluidine blue (final magnification, × 100; scale bar is 25 μm). Single and double arrows indicate strongly and weakly NSE-positive cells, respectively, corresponding to immature and mature DCs.

Phenotype of mouse monocytes

An extensive phenotypic analysis of mouse monocytes (Figure 1D) was performed on lysis buffer-treated samples of B cell-depleted heparinized blood or bone marrow, by triple immunofluorescence staining after gating on monocytes on the basis of their CD11b versus Ly-6C profile, as shown in Figure 1A. Monocytes from C57BL/6 mice expressed high levels of Ly-6C and CD62L (L-selectin); intermediate levels of CD11b, Gr-1, FcγRII and III (CD16 and CD32), and CD44; low levels of F4/80; and null to low levels of CD43 and CD24 (HSA). Monocytes were negative for the DC markers CD11c, MHC II, and DEC-205; the costimulation markers CD40 and CD86; the B-cell and plasmacytoid cell markers B220 and IL-3Rα; the T-cell markers CD4, CD8α, and CD90 (Thy-1); and the activation marker CD69. As shown in Figure 1D, BALB/c monocytes displayed a similar phenotype except for CD43 and CD24, which were expressed at higher levels than in C57BL/6. No significant phenotypic differences were observed between blood and bone marrow monocytes (not shown).

Finally the expression of TLR-4 and TLR-9, recognizing bacterial LPSs and cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) oligodeoxynucleotides, respectively, was analyzed by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR). As illustrated in Figure 1E, monocytes expressed TLR-4- but not TLR-9-specific mRNA, which were both expressed by splenic CD8- and CD8+ DCs, used as positive controls for TLR-4 and TLR-9 in these experiments. In accordance with these data, monocyte-derived DCs responded to LPS (Figure 4A) but not to CpG oligodeoxynucleotides (not shown).

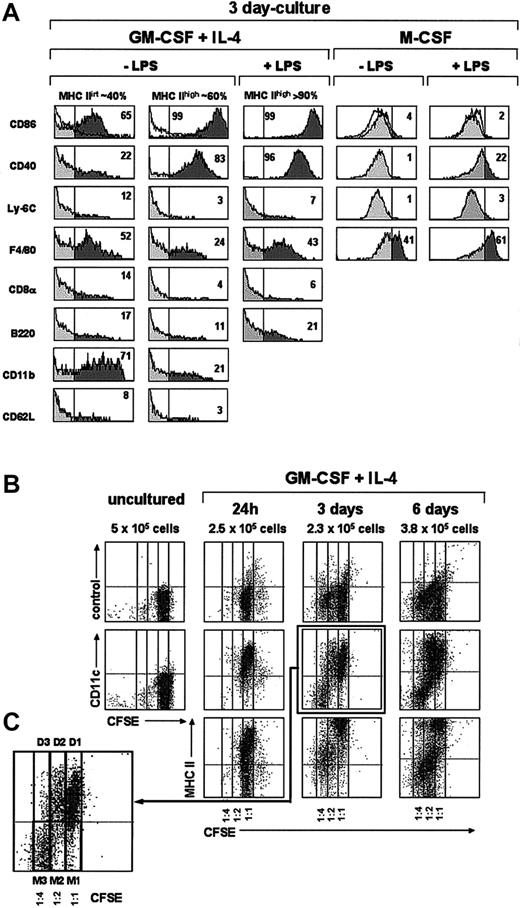

Phenotypic and cell proliferation analysis of monocytes cultured with GM-CSF plus IL-4 or M-CSF. (A) Histograms show the expression of the indicated markers by MHC IIint and MHC IIhi DCs from 3-day cultures of monocytes with GM-CSF plus IL-4 or M-CSF in the presence or absence of LPS (only the phenotype of MHC IIhi DCs is shown for cultures with GM-CSF plus IL-4 supplemented with LPS because MHC IIint DCs are almost absent in these cultures). The percentage of cells with a fluorescence intensity over the vertical lines (dark area of the gray profiles), corresponding to the upper limit of control background staining (white profiles shown in the CD86 histograms), is indicated. Data are representative of 4 experiments with similar results. (B) Cell proliferation in cultures of monocytes with GM-CSF and IL-4 was assessed after labeling with the intracellular fluorescent dye CFSE. Density plots show CFSE-versus-CD11c staining profiles of monocytes loaded with CFSE before culture, and the CFSE-versus-CD11c, -MHC II, and control background staining profiles of CFSE-loaded monocytes cultured with GM-CSF plus IL-4 for the indicated times. For each culture time, the total number of cells per well is indicated. CFSE dilution allowed us to assess whether cells had undergone 0, 1, or 2 cell divisions (1:1, 1:2, and 1:4 CFSE dilution, respectively). (C) Higher magnification of the CFSE-versus-CD11c profile from a 3-day culture showing DCs (D1) generated from monocytes that did not divide (M1), DCs (D2) generated from monocytes that had undergone 1 cell division (M2), and monocytes that had undergone 2 cell divisions (M3).

Phenotypic and cell proliferation analysis of monocytes cultured with GM-CSF plus IL-4 or M-CSF. (A) Histograms show the expression of the indicated markers by MHC IIint and MHC IIhi DCs from 3-day cultures of monocytes with GM-CSF plus IL-4 or M-CSF in the presence or absence of LPS (only the phenotype of MHC IIhi DCs is shown for cultures with GM-CSF plus IL-4 supplemented with LPS because MHC IIint DCs are almost absent in these cultures). The percentage of cells with a fluorescence intensity over the vertical lines (dark area of the gray profiles), corresponding to the upper limit of control background staining (white profiles shown in the CD86 histograms), is indicated. Data are representative of 4 experiments with similar results. (B) Cell proliferation in cultures of monocytes with GM-CSF and IL-4 was assessed after labeling with the intracellular fluorescent dye CFSE. Density plots show CFSE-versus-CD11c staining profiles of monocytes loaded with CFSE before culture, and the CFSE-versus-CD11c, -MHC II, and control background staining profiles of CFSE-loaded monocytes cultured with GM-CSF plus IL-4 for the indicated times. For each culture time, the total number of cells per well is indicated. CFSE dilution allowed us to assess whether cells had undergone 0, 1, or 2 cell divisions (1:1, 1:2, and 1:4 CFSE dilution, respectively). (C) Higher magnification of the CFSE-versus-CD11c profile from a 3-day culture showing DCs (D1) generated from monocytes that did not divide (M1), DCs (D2) generated from monocytes that had undergone 1 cell division (M2), and monocytes that had undergone 2 cell divisions (M3).

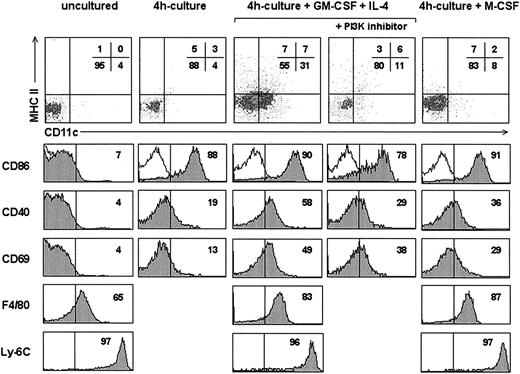

In vitro differentiation of DCs from monocytes

Monocytes purified from C57BL/6 mouse bone marrow were cultured under the conditions known to induce in the human system their differentiation into DCs or macrophages, that is, in the presence of GM-CFS plus IL-4 or M-CFS.9 After 4 hours in culture with either GM-CSF plus IL-4 or M-CSF (Figure 2), CD11c and MHC II expression remained unchanged although a slight increase in CD11c was observed in cultures with GM-CSF plus IL-4. In contrast, after this culture time, a significant up-regulation of CD86, CD40, and F4/80 occurred in cultures with GM-CSF and IL-4, and to a lesser extent in cultures with M-CSF. Interestingly, monocytes cultured in the absence of cytokines for 4 hours also underwent the up-regulation of CD86 compared to uncultured isolated monocytes. These data suggest that monocytes were progressively activated first by the culture period (probably due to the adherence to the plastic culture surface), and second, by the effect of cytokines, which led to the expression of the activation molecule CD69, not observed in cytokine-free cultures. It can be hypothesized that the initial up-regulation of CD86 observed after cytokine-free culture would result from a partial activation process, whereas culture with GM-CSF plus IL-4 or M-CSF would be required to induce the up-regulation of the activation marker CD69. On the other hand, the positive regulation of CD11c expression observed after 4 hours of culture with GM-CSF plus IL-4 suggests the onset of monocyte differentiation to the DC lineage. To address whether this small but noticeable increase in CD11c expression observed with GM-CSF plus IL-4 could be an artifact, cultures were treated with an inhibitor of PI3K, because induction of CD11c expression after engagement of GM-CSF receptor has been claimed to be regulated by PI3K. As shown in Figure 2, CD11c up-regulation did not occur in 4-hour cultures in the presence of GM-CSF plus IL-4 when the PI3K inhibitor Ly 294002 was added, supporting that the slight CD11c up-regulation observed after 4 hours was evidence of the induction of monocyte differentiation into DCs. Treatment of GM-CSF plus IL-4 4-hour cultures with Ly 294002 also determined a partial inhibition of CD86, CD40, and CD69 up-regulation, suggesting the involvement of PI3K signaling in monocyte activation, in accordance with the role of PI3K in T- and B- cell activation.10

Analysis of 4-hour monocyte cultures. Density plots show the CD11c versus MHC II profile of uncultured monocytes or monocytes cultured for 4 hours in the absence or presence of GM-CSF plus IL-4 or M-CSF. Some cultures with GM-CSF plus IL-4 were treated with the PI3K inhibitor Ly 294002. Gray profiles show the expression of the indicated markers by monocytes in each culture condition. The percentage of cells with a fluorescence intensity over the vertical lines, corresponding to the upper limit of control background staining (white profiles shown in the CD86 histograms), is indicated. Data are representative of 2 experiments with similar results.

Analysis of 4-hour monocyte cultures. Density plots show the CD11c versus MHC II profile of uncultured monocytes or monocytes cultured for 4 hours in the absence or presence of GM-CSF plus IL-4 or M-CSF. Some cultures with GM-CSF plus IL-4 were treated with the PI3K inhibitor Ly 294002. Gray profiles show the expression of the indicated markers by monocytes in each culture condition. The percentage of cells with a fluorescence intensity over the vertical lines, corresponding to the upper limit of control background staining (white profiles shown in the CD86 histograms), is indicated. Data are representative of 2 experiments with similar results.

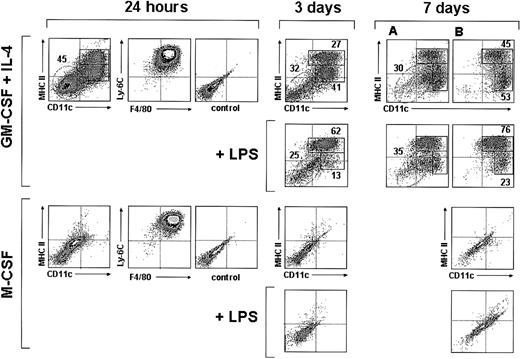

Interestingly, 24 hours after culture in the presence of GM-CSF plus IL-4, around 50% of the monocytes had up-regulated both CD11c and MHC II (Figure 3), indicating that a large proportion of monocytes had already differentiated into DCs; interestingly at this culture time monocyte-derived DCs still displayed a high expression level of F4/80 and Ly-6C, similar to that found after 4 hours, and therefore represent early immature DCs (Figure 2). By day 3 the percentage of CD11c+ MHC II+ cells was around 70% (Figure 3); among these cells 2 different subpopulations can be distinguished on the basis of their MHC II levels: around 40% were MHC IIint and around 60% were MHC IIhigh cells. Their phenotypic analysis at day 3 (Figure 4A) revealed that these 2 subpopulations had completely down-regulated Ly-6C and CD62L and underwent a significant down-regulation of F4/80 and CD11b. They, corresponded to immature and mature DCs, respectively, the latter expressing higher levels of CD86 and CD40 and lower F4/80 and CD11b levels. This was confirmed by analyzing the effect of LPS on day 3 and day 7 cultures (Figures 3-4A). After incubation with LPS the vast majority of CD11c+ cells expressed high levels of MHC II, CD86, and CD40 (data on CD86 and CD40 expression shown for day-3 but not for day-7 cultures), and therefore corresponded to mature monocyte-derived DCs. DCs generated from monocytes were negative for the molecules CD8α and B220 (Figure 4A), expressed by defined subsets of DCs present in mouse lymphoid organs.6,11 In conclusion, in vitro differentiation of monocytes into mature DCs involves the following sequence:

Monocytes CD11c- MHC II- CD86-/CD40- F4/80low Ly-6Chigh →

Activated monocytes CD11clow MHC II- CD86int/CD40int F4/80int Ly-6Chigh →

Early immature DCs CD11chigh MHC IIintCD86int/CD40int F4/80high Ly-6Chigh →

Immature DCs CD11chigh MHC IIint CD86int/CD40int F4/80int Ly-6C- →

Mature DCs CD11chigh MHC IIhigh CD86high/CD40high F4/80int Ly-6C-

Analysis of monocyte cultures in the presence of GM-CSF plus IL-4 or M-CSF. Density plots show the CD11c versus MHC II, F4/80 versus Ly-6C, and the control background staining profiles of monocytes cultured with GM-CSF plus IL-4 or M-CSF for 24 hours, and the CD11c versus MHC II profiles of monocytes cultured with GM-CSF plus IL-4 or M-CSF for 3 or 7 days in the presence or absence of LPS. The percentages of MHC IIint and MHC IIhi DCs (solid-line boxes) and monocytes/macrophages (dashed-line ovals) are indicated. Macrophages present in day-7 cultures with GM-CSF plus IL-4 (dashed-line ovals in panel A) were gated out in panel B on the basis of their autofluorescence in the FL3 channel of the flow cytometer (CD11c and MHC II expression was analyzed in the FL1 and FL2 channels, respectively). Data are representative of 4 experiments with similar results.

Analysis of monocyte cultures in the presence of GM-CSF plus IL-4 or M-CSF. Density plots show the CD11c versus MHC II, F4/80 versus Ly-6C, and the control background staining profiles of monocytes cultured with GM-CSF plus IL-4 or M-CSF for 24 hours, and the CD11c versus MHC II profiles of monocytes cultured with GM-CSF plus IL-4 or M-CSF for 3 or 7 days in the presence or absence of LPS. The percentages of MHC IIint and MHC IIhi DCs (solid-line boxes) and monocytes/macrophages (dashed-line ovals) are indicated. Macrophages present in day-7 cultures with GM-CSF plus IL-4 (dashed-line ovals in panel A) were gated out in panel B on the basis of their autofluorescence in the FL3 channel of the flow cytometer (CD11c and MHC II expression was analyzed in the FL1 and FL2 channels, respectively). Data are representative of 4 experiments with similar results.

A similar percentage of DCs was obtained from day-3 and day-7 cultures, although these cultures differed with regard to the phenotype of CD11c- MHC II- cells. At day-3 cultures these cells expressed Ly6-C and intermediate levels of F4/80 (not shown) and most likely corresponded to monocytes. However, CD11c- MHC II- cells from day-7 cultures were Ly-6C- and F4/80high (not shown) and strongly autofluorescent (Figure 3; 7 days, panel A), had high FSC and SSC values, and therefore corresponded to macrophages. To allow a more accurate analysis of immature and mature DC subpopulations in day-7 culture profiles, macrophages were gated out on the basis of their autofluorescence in the FL3 channel of the flow cytometer (Figure 3; panels in B; CD11c and MHC II expression was analyzed in the FL2 and FL1 channels, respectively).

When cultured in the presence of M-CSF, monocytes differentiated into CD11c- MHC II- CD86-CD40-F4/80+ macrophages, but no DCs were generated under these culture conditions (Figure 3). On LPS treatment, macrophages underwent a slight but significant up-regulation of CD40 and F4/80, reflecting an activated state.

Analysis of cell proliferation during in vitro DC differentiation from monocytes was performed after labeling with CFSE and is shown in Figure 4B, in which CFSE dilution allowed to determine whether cells had undergone 0, 1, or 2 cell divisions (1:1, 1:2, and 1:4 CFSE dilution, respectively).

After 24 hours in culture most monocytes had differentiated into CD11c+ MHC II int immature DCs, although some nondifferentiated monocytes remained. No cell divisions occurred at this culture time (no CFSE dilution was detected). These immature DCs (corresponding to cells with a 1:1 CFSE dilution) underwent a progressive maturation process in culture involving the up-regulation of MHC II from 24 hours to 3 days, and a partial down-regulation of Ly6-C from 3 to 6 days (data not show for Ly-6C). This result contrasts with that from non-CFSE-loaded monocyte cultures shown in Figure 4A, in which a complete Ly6-C down-regulation occurred after 3 days in culture. This discrepancy could reflect a delayed process of DC differentiation due to the CFSE toxicity.

Interestingly, after 3 days in culture a proportion of the monocytes had undergone one or 2 cell divisions, corresponding to a 1:2 and 1:4 CFSE dilution, respectively (Figure 4C), but no additional cell divisions were detectable in day 6 cultures. The majority of monocytes that had gone through 2 cell divisions (1:4 CFSE dilution) maintained their CD11c- Ly-6Chigh phenotype after 3 and 6 days in culture. However, cells that had undergone one cell division at day 3 or day 6 (1:2 CFSE dilution) were heterogenous since they comprised immature CD11c+ DCs, which expressed low MHC II levels, as well as monocytes; at day 6 some of these monocytes differentiated into macrophages, as assessed by their high F4/80 expression and their FSC versus SSC profile (not shown).

The morphologic analysis of in vitro differentiated monocytes, by phase-contrast microscopy and NSE staining, revealed that monocyte cultures with GM-CSF plus IL-4 generated cells with characteristic DC morphology (Figure 5). Among non-LPS-treated cells, 2 different cell populations were distinguished on the basis of their NSE staining intensity. Cells strongly positive for NSE were small, rounded-shaped cells (8-10 μm in size); cells with weak NSE staining, located in the perinuclear region, were 8 to 15 μm in size and displayed an irregular shape with short cytoplasmic processes. Based on their morphology, and the phenotypic analyses shown in Figures 3 and 4A, strongly and weakly positive cells most likely correspond to immature and mature DCs, respectively. In addition, some NSE+ cells, with characteristic macrophage morphology, were also present in the cultures. After LPS treatment the majority of the cells were similar to the NSE weakly positive cells present in non-LPS-treated cultures. On the other hand LPS induced an increase in DC size and the appearance of long cytoplasmic processes, as assessed by phase-contrast microscopy. Culture in the presence of M-CSF led to monocyte differentiation into macrophages, characterized by the development of cytoplasmic granules and vesicles and a strong NSE activity; LPS treatment induced an increase in size and development of cytoplasmic vesicles, paralleled by a reduction in NSE activity.

T-cell stimulatory capacity of monocyte-derived DCs

To assess the APC capacity of monocyte-derived DCs, LPS-treated or untreated DCs from day 3 cultures of monocytes with GM-CSF and IL-4, LPS-treated or untreated macrophages from day 3 cultures of monocytes with M-CSF, and uncultured monocytes or splenic DCs from C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice were tested in a mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) assay by culturing them with mesenteric lymph node T cells from BALB/c (H-2d) mice, at different APC/T-cell ratios. As assessed by [3H]-thymidine incorporation (Figure 6A), LPS-matured monocyte-derived DCs induced a strong T-cell proliferation, comparable to that obtained with splenic DCs, the latter used as positive control APCs in these assays. No significant T-cell proliferation was induced by LPS-treated or untreated monocyte-derived macrophages, or uncultured monocytes. These data demonstrate that DC differentiation from monocytes involved the acquisition of a highly efficient T-cell stimulatory capacity.

In vitro functional analysis on monocytes and monocyte-derived DCs. (A) T-cell stimulation potential of uncultured bone marrow monocytes, LPS-treated or untreated DCs from day-3 cultures of monocytes with GM-CSF and IL-4, LPS-treated or untreated macrophages from day-3 cultures of monocytes with M-CSF, and splenic DCs were tested in an MLR assay, using different APC/T-cell ratios. T-cell proliferation was determined by [3H]-thymidine uptake (error bars represent the SD for triplicate cultures). (B) Monocyte reverse transendothelial migration assay. Contour plots show the CD11c-versus-MHC II and F4/80-versus-Ly-6C profiles of reverse transendothelial migrated cells, corresponding to early immature DCs. The percentage of cells in each quadrant is indicated. Data are representative of 3 experiments with similar results.

In vitro functional analysis on monocytes and monocyte-derived DCs. (A) T-cell stimulation potential of uncultured bone marrow monocytes, LPS-treated or untreated DCs from day-3 cultures of monocytes with GM-CSF and IL-4, LPS-treated or untreated macrophages from day-3 cultures of monocytes with M-CSF, and splenic DCs were tested in an MLR assay, using different APC/T-cell ratios. T-cell proliferation was determined by [3H]-thymidine uptake (error bars represent the SD for triplicate cultures). (B) Monocyte reverse transendothelial migration assay. Contour plots show the CD11c-versus-MHC II and F4/80-versus-Ly-6C profiles of reverse transendothelial migrated cells, corresponding to early immature DCs. The percentage of cells in each quadrant is indicated. Data are representative of 3 experiments with similar results.

Monocyte differentiation into DCs during in vitro reverse transendothelial migration

Because monocyte differentiation into DCs appears to occur in vivo on entry of extravascularly located monocytes into the lymphatics,12 mouse bone marrow monocytes were analyzed for their capacity to differentiate into DCs by using the reverse transendothelial migration assay originally designed for human monocytes by Randolph et al,2 claimed to constitute a more physiologic experimental system of monocyte differentiation into DCs. In these assays, purified monocytes were allowed to migrate for 16 hours over confluent HUVEC monolayers grown on type I collagen gel, in the absence or presence of zymosan, to allow their migration through the endothelial layer into the collagen gel (“Materials and methods”). Reverse-transmigrated cells were incubated for 2 days and obtained from the culture medium overlying the endothelium and analyzed after gating out the endothelial cells from the FACS profiles on the basis of their null expression of CD45. On reverse transmigration from collagen gels containing zymosan (Figure 6B), up to 80% of monocytes had differentiated into DCs, as assessed by the up-regulation of CD11c. In addition, the majority of CD11c+ DCs had up-regulated MHC II to intermediate levels, and expressed high levels of both Ly-6C and F4/80, that is, a phenotype comparable to that described for early immature DCs obtained from monocytes after 24 hours of culture in the presence of GM-CSF plus IL-4 (Figure 3). Interestingly, similar results were obtained when zymosan was not included in the collagen gels, indicating that in these assays murine DC maturation was not influenced significantly by zymosan uptake by monocytes, as reported for human monocytes.2

In vivo derivation of DCs from monocytes

The results show that mouse monocytes can be differentiated in vitro on culture with GM-CSF and IL-4, or after reverse transmigration, as previously reported for human monocytes, and demonstrate that also in the murine system monocytes represent DC precursors. However, an especially controversial issue dealing with DC derivation from monocytes is whether this process occurs in vivo in steady-state conditions, because this has not been formally demonstrated, and what the correlation is between monocyte-derived DCs and the DCs subsets described in vivo.

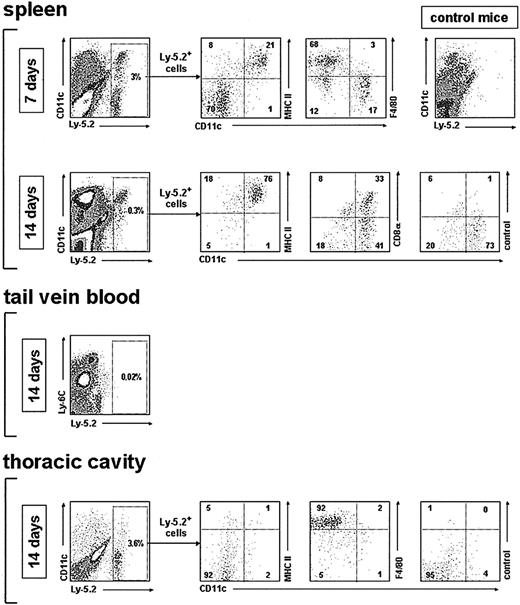

To answer these questions, purified bone marrow monocytes were assayed for their potential to generate DCs, on intravenous injection into γ-irradiated recipients, using an Ly5.1/5.2 system to trace donor-type Ly5.2+ cells (Figure 7). This experimental system, previously used in our laboratory to trace the progeny of lymphoid precursors13,14 or common CD11c+ MHC II- DC precursors,5 was used here because after intravenous transfer of monocytes into nonirradiated recipients, very few donor-derived cells were detected (data not shown).

Analysis of the in vivo DC reconstitution potential of monocytes after transfer into irradiated recipients. Density plots show the phenotypic analysis of monocyte-derived cells after gating for Ly-5.2+ cells, performed on spleen low-density cell fractions, tail vein blood, and thoracic cavity, at the indicated times after monocyte transfer into irradiated recipients. Control mice were injected intravenously with Ly-5.1 recipient-type bone marrow cells. The percentage of Ly-5.2+ cells as well as the percentage of cells in each quadrant of the density plots corresponding to the phenotypic analysis is indicated. Data are representative of 4 (spleen) and 2 (tail vein and thoracic cavity) experiments with similar results.

Analysis of the in vivo DC reconstitution potential of monocytes after transfer into irradiated recipients. Density plots show the phenotypic analysis of monocyte-derived cells after gating for Ly-5.2+ cells, performed on spleen low-density cell fractions, tail vein blood, and thoracic cavity, at the indicated times after monocyte transfer into irradiated recipients. Control mice were injected intravenously with Ly-5.1 recipient-type bone marrow cells. The percentage of Ly-5.2+ cells as well as the percentage of cells in each quadrant of the density plots corresponding to the phenotypic analysis is indicated. Data are representative of 4 (spleen) and 2 (tail vein and thoracic cavity) experiments with similar results.

Analysis of DC-enriched splenic low-density cell fractions revealed that 7 days after transfer of monocytes, approximately 20% of donor-type Ly-5.2+ cells corresponded to CD11c+ MHC II+ DCs, and about 70% of Ly-5.2+ cells were CD11c- MHC II- cells, including mostly F4/80high macrophages, although some CD11c- MHC II- F4/80low monocytes were also observed. By day 14 after transfer, all splenic donor-type Ly-5.2+ cells were CD11c+ MHC II+ DCs, but represented only a minor proportion of total splenic DCs (around 2% in the experiment shown in Figure 7).

Interestingly, both CD8α- and CD8α+ DCs, representing the 2 main splenic DC subsets found in control mice, were generated from monocytes. At this time after transfer, the CD8α-/CD8α+ ratio was 45:55, a similar ratio to that obtained after transfer of CD4low lymphoid precursors13 or blood common CD11c+ MHC II- DC precursors.5 No Ly-5.2+ cells were detected in blood samples obtained directly from the tail vein at day 7 or 14 after transfer (Figure 7; data not shown for day 7).

Finally, analysis of thoracic cavity lavage specimens revealed that on extravasation and homing to the thoracic cavity, transferred monocytes differentiate efficiently into CD11c-, MHC II-, F4/80high macrophages. Similar results were obtained after analysis of Ly-5.2+ cells in the peritoneal cavity (not shown). No granulocytes or lymphocytes were detected among the Ly-5.2+ cells, indicating that DCs generated on monocyte transfer resulted from the DC differentiation potential of monocytes and not from the activity of myeloid or lymphoid precursors transferred along with monocytes.

Discussion

Here we report the phenotypic and functional characterization of mouse monocytes isolated from blood and bone marrow, because the available information on these cells was limited to few reports dealing essentially to their development and migratory properties in genetically modified mice.14-18 Our results revealed that mouse monocytes isolated from blood or bone marrow displayed similar phenotypic characteristics to those reported for human monocytes and can be differentiated into macrophages in the presence of M-CSF.

More important, the data presented in this report show that mouse monocytes can be driven to differentiate into functional DCs when cultured in the presence of the same cytokines that control this differentiation pathway in the human system. In addition, we demonstrate that the differentiation of monocytes into DCs involves an early monocyte activation phase paralleled by the induction of CD11c expression and could be achieved only 24 hours after culture with GM-CSF plus IL-4, whereas longer culture periods appear to be required in the human system.9 Analysis of cell proliferation by CFSE loading, performed in cultures of monocytes with GM-CSF plus IL4, revealed that mouse monocyte differentiation into DCs involved up to 2 monocyte cell divisions during the first 6 days of culture. This contrasts to that described for the process of human DC differentiation from monocytes9 or CD14+ CD1a- precursors derived from CD34+ cord blood or bone marrow precursors,19,20 reported to occur without cell proliferation.

Monocyte differentiation into DCs also occurred on in vitro reverse transendothelial migration, although in our assays murine DC differentiation was not dependent on zymosan uptake by monocytes in the collagen gel, suggesting that phagocytosis did not influence monocyte differentiation into DCs in these experiments. Interestingly, reverse transmigrated cells had a phenotype corresponding to that of early immature DCs obtained after 24 hours of culture of monocytes in the presence of GM-CSF plus IL-4 (Figure 3), suggesting that additional stimuli, or an extended period in culture, are required for a full maturation of DCs obtained after reverse transmigration. These results contrast with those reported by Randolph et al2 for reverse transmigration assays with human monocytes, in which zymosan uptake was required to induce DC maturation on reversed transmigrated cells. Alternatively, our data could reflect a defective maturation process due to the fact that reverse transmigration of murine monocytes proceeded through a human endothelial cell monolayer.

On the other hand, the results derived from monocyte transfers into irradiated mice suggest that on homing to the spleen, monocytes generated DCs following a physiologic differentiation pathway, implying the formation of CD8α- and CD8α+ DCs. Besides, our data demonstrate that monocytes can differentiate in DCs similar to those characteristic of control spleen, that is, CD8α- and CD8α+ DCs, providing the first indication of the physiologic significance of monocyte-derived DCs with regard to their correlation to previously defined DC subpopulations. Interestingly, Bruno et al21 have reported that a bone marrow cell population expressing, as monocytes, Ly-6C, CD11b, and Gr-1, but being CD11c+ and F4/80- in contrast to monocytes, was endowed with the potential to generate CD8α- and CD8α+ DCs in fetal thymic organ cultures. Additional experiments are needed to establish the possible correlation between monocytes and this DC precursor population.

Finally, our results support the hypothesis that monocytes can generate DCs not only on reverse transendothelial migration to the lymphatics and homing to the lymph nodes as previously proposed,2,4 but also on extravasation from the bloodstream during homing to the spleen, suggesting that monocytes represent immediate precursors of DCs located in peripheral lymphoid organs. On the other hand, the mechanisms determining differentiation of monocytes into DCs or macrophages in vivo remain largely unknown. Monocytes have been claimed to differentiate into DCs on extravasation in inflammatory sites related to epithelial surface and subsequent transendothelial migration into the lymphatics after antigen uptake and migration to the lymph nodes.4 In addition, here we have shown their capacity to differentiate into CD8α- and CD8α+ DCs on migration to the spleen, suggesting that monocytes might participate in DC generation under steady-state conditions. However, DCs do not develop in mice homozygous for a dominant-negative mutation in the Ikaros gene (Ikaros DN-/- mice), which display a profound deficiency in lymphoid but not myeloid differentiation, and consequently have a normal monocyte development.22 The study of monocyte differentiation into DCs during ongoing immune and inflammatory responses, and in mice deficient for molecules controlling DC differentiation such as Ikaros, RelB, PU.1, ICSBP-1, and Id-2, should contribute significantly to our understanding of DC development.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, November 20, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0286.

Supported by the European Comission (grant no. QLRT-1999-00276), the Comunidad de Madrid of Spain (grant no. 08.1/0076/2000), and the Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología of Spain (grant no. BOS 2000-0558). B.L. is supported by a fellowship of the Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte of Spain.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Angel Corbí for helpful advice and A. Rolink for the anti-CD40 hybridoma FGK45.

![Figure 6. In vitro functional analysis on monocytes and monocyte-derived DCs. (A) T-cell stimulation potential of uncultured bone marrow monocytes, LPS-treated or untreated DCs from day-3 cultures of monocytes with GM-CSF and IL-4, LPS-treated or untreated macrophages from day-3 cultures of monocytes with M-CSF, and splenic DCs were tested in an MLR assay, using different APC/T-cell ratios. T-cell proliferation was determined by [3H]-thymidine uptake (error bars represent the SD for triplicate cultures). (B) Monocyte reverse transendothelial migration assay. Contour plots show the CD11c-versus-MHC II and F4/80-versus-Ly-6C profiles of reverse transendothelial migrated cells, corresponding to early immature DCs. The percentage of cells in each quadrant is indicated. Data are representative of 3 experiments with similar results.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/103/7/10.1182_blood-2003-01-0286/6/m_zh80070458850006.jpeg?Expires=1769092008&Signature=D2WOStg9yIG-rUC25zW6GJry0foZ9qbv3HR1g2IX-PTOi1emII6j3VhGk4ANjfLcIziS~FBFYymSMa5bRqoWIoUN7pa2xGVEAneXz8hWcW6Bo-L1O4qxb7Ihv7X-ktxaraPAyPQD649k86fr2chQ0P9qAGe6R3UfBJVUHA0Phv6MxZLQAHQxly72zzrC9kK6Komt34IIOJ-oaRhwfQejlcMCdLTHh9HZgor3G70Y3gBdfgcrp9sB8idrtehAE1J19DTUOGT0GggdfgnjSoTcvLEMqHK2tH344Qhxc-WJjmvHKwGJqAg2ak-XxvE6SgYgUXnLcKbXYx2~Dg3sp8za2w__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal