Abstract

Activating mutations of the FLT3 receptor tyrosine kinase are common in acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) but are rare in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). We have recently shown that FLT3 is highly expressed and often mutated in ALLs with rearrangement of the mixed lineage leukemia (MLL) gene on chromosome 11q23. Because hyperdiploid ALL samples also show high-level expression of FLT3, we searched for the presence of FLT3 mutations in leukemic blasts from 71 patients with ALL. The data show that approximately 25% (6 of 25) of hyperdiploid ALL samples possess FLT3 mutations, whereas only 1 of 29 TEL/AML1-rearranged samples harbored mutations (P = .04, Fisher exact test). Three mutations are novel in-frame deletions within a 7-amino acid region of the receptor juxtamembrane domain. Finally, 3 samples from patients whose disease would relapse harbored FLT3 mutations. These data suggest that patients with hyperdiploid or relapsed ALL might be considered candidates for therapy with newly described small-molecule FLT3 inhibitors. (Blood. 2004;103: 3544-3546)

Introduction

The FMS-related tyrosine kinase-3 (FLT3) is a receptor tyrosine kinase expressed in early hematopoietic progenitors that plays an important role in hematopoietic development.1,2 Multiple studies have shown that activating mutations of FLT3 are common in blasts from patients diagnosed with acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) but are rarely found in adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).2-4 We have recently shown that FLT3 is consistently highly expressed in MLL rearranged acute lymphoblastic leukemias (MLLs).5 This prompted analysis for FLT3 mutations in MLL, where we found approximately 15% contain activating mutations in the receptor activation loop.6 A large gene expression analysis of childhood ALL samples has shown that high-level FLT3 expression is also found in ALL samples containing more than 50 chromosomes (hyperdiploid ALL).7 Here we show that activating FLT3 mutations are found in diagnostic specimens from 6 of 25 patients with hyperdiploidALL, but only 1 of 29 patients with TEL/AML1-rearranged ALL. Also, 3 of 16 patients with leukemia who would ultimately have a relapse harbored FLT3 mutations. Most of the mutations are previously described activation loop mutations, but 4 are new mutations consisting of either small deletions or insertions in the juxtamembrane region of the receptor. These data suggest that patients with hyperdiploid or relapsed ALL should be considered possible candidates for therapy with recently described small-molecule FLT3 inhibitors.8-11

Study design

Patient samples

Leukemia samples were obtained from either bone marrow or peripheral blood at diagnosis from patients with ALL. The peripheral blood samples all had more than 10% blasts at diagnosis. Patients were treated according to Dana Farber Cancer Institute protocols 91-001, 95-001, and 00-001. Informed consent was obtained from all patients after approval of the Institutional Review Board. Standard cytogenetic analysis was performed on all samples. TEL-AML1 translocations were determined by florescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as previously described.12

Mutation detection

gDNA was extracted from leukemia samples with Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Mutations in the juxtamembrane domain were identified by amplifying a region spanning exons 14 and 15 with primers 14F (TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTCAATTTAGGTATGAAAGCC) and 15R (GAGGAAACAGCTATGACCCTTTCAGCATTTTGACGGCAACC). The upstream primer in this reaction was fluorescently labeled (6-FAM) to allow sizing of all products when electrophoresed on a sequencing apparatus (Model 377, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The area under the curve of a variant product was divided by the total area under all curves to approximate the percentage of variant alleles in a sample. When variant products were determined to constitute more than 30% of the signal, the sample was directly sequenced following the initial PCR. Samples with no detectable length mutations were also directly sequenced. For a sample with a less abundant variant (1%-30%), the PCR product was run on a 1.5% agarose gel, and the variant product was cut from the gel and reamplified with the original primers prior to sequencing.

Activation loop mutations were determined by PCR amplification with primers 20F (TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTCCGCCAGGAACGTGCTTG) and 20R (CAGGAAACAGCTATGACCGCAGCCTCACATTGCCCC), followed by EcoRV digestion. EcoRV digests wild-type but not mutant fragments at the recognition site composed by codons 835 and 836 (GATATC). A second round of PCR was performed to amplify the uncut fragments. The products of the second PCR were sequenced. To determine an estimate of the percentage of mutant alleles in a sample containing an FLT3 mutation, PCR was repeated in duplicate as described. In one of the reactions the 20F primer was substituted with a TET-labeled 20F primer, and in the other reaction the 20R primer was replaced with a 6-FAM-labeled 20R primer. PCR amplicons were subsequently digested with EcoRV and the percentage of mutant (undigested) amplicons present was determined by dividing the area under the mutant curve by the total area under the curves from the digested and undigested products. Samples with more than 2% mutant alleles were determined to be positive.

Results and discussion

We recently demonstrated that consistent high-level expression of FLT3 in MLL identifies a subtype of ALL that often harbors FLT3 mutations and have validated FLT3 as a potential therapeutic target in this leukemia.5,6 Because FLT3 is also consistently expressed at high levels in hyperdiploid ALL, we searched for FLT3 mutations in 71 childhood ALL samples to determine if FLT3 mutations are more prevalent in hyperdiploid as compared to other ALLs. We found 6 of 25 hyperdiploid ALL samples contain mutations that are predicted to lead to constitutive activation of the receptor, whereas only one of 29 TEL/AML1-rearranged samples harbored a FLT3 mutation (Table 1). Also, none of 8 ALL samples with other cytogenetic characteristics and 3 of 9 samples from which cytogenetics were not available possessed FLT3 mutations. Thus, 10 of 71 samples possessed FLT3 mutations with a significant association between FLT3 mutations and hyperdiploid ALL (P = .04).

FLT3 mutations in 71 childhood ALL samples

Primary identification no. (% blasts in sample) . | Exon 14-15, nucleotide positions (% mutant alleles) . | Activation loop, mutation (% mutant alleles) . | Remission status . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperdiploid ALL, more than 50 chromosomes (n = 25) | |||

| ALL-6 (88) | — | I836Δ (30) | CCR |

| ALL-7 (90) | — | D835Y (20) | CCR |

| ALL-12 (89) | Δ 1770-1784 plus GA1787A1788 - > GGG (30) | — | CCR |

| ALL-25 (95) | TTC1770-> TTA Δ 1771-1782 (15) | — | CCR |

| ALL-34 (22) | — | D835V (11) | CCR |

| ALL-24 (95) | Δ 1777-1779 (47) | — | Relapse |

| TEL/AML1 (n = 29) | CCR | ||

| ALL-68 (95) | 30bp ITD (5) | — | — |

| Other: 1 E2A/PBX, 2 pseudodiploid, 5 diploid (n = 8) | — | — | — |

| Cytogenetics not available (n = 9) | |||

| ALL-35 (35) | — | D835E (7) | CCR |

| ALL-19 (70) | — | I836Δ (10) | Relapse |

| ALL-21 (30) | Δ 1732-1734 plus 18-bp insertion* (18) | — | Relapse |

Primary identification no. (% blasts in sample) . | Exon 14-15, nucleotide positions (% mutant alleles) . | Activation loop, mutation (% mutant alleles) . | Remission status . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperdiploid ALL, more than 50 chromosomes (n = 25) | |||

| ALL-6 (88) | — | I836Δ (30) | CCR |

| ALL-7 (90) | — | D835Y (20) | CCR |

| ALL-12 (89) | Δ 1770-1784 plus GA1787A1788 - > GGG (30) | — | CCR |

| ALL-25 (95) | TTC1770-> TTA Δ 1771-1782 (15) | — | CCR |

| ALL-34 (22) | — | D835V (11) | CCR |

| ALL-24 (95) | Δ 1777-1779 (47) | — | Relapse |

| TEL/AML1 (n = 29) | CCR | ||

| ALL-68 (95) | 30bp ITD (5) | — | — |

| Other: 1 E2A/PBX, 2 pseudodiploid, 5 diploid (n = 8) | — | — | — |

| Cytogenetics not available (n = 9) | |||

| ALL-35 (35) | — | D835E (7) | CCR |

| ALL-19 (70) | — | I836Δ (10) | Relapse |

| ALL-21 (30) | Δ 1732-1734 plus 18-bp insertion* (18) | — | Relapse |

Seventy-one ALL samples were assessed for the presence of mutations in the juxtamembrane and activation loop regions of FLT3. The cytogenetic abnormalities (when available) are noted. The types of FLT3 mutations either in the juxtamembrane region or in the activation loop are noted.

CCR indicates complete continuous remission. — indicates no motion.

The 18-bp insertion (AACTTAAGGAACCCACCA) is inserted 3′ to nucleotide 1731.

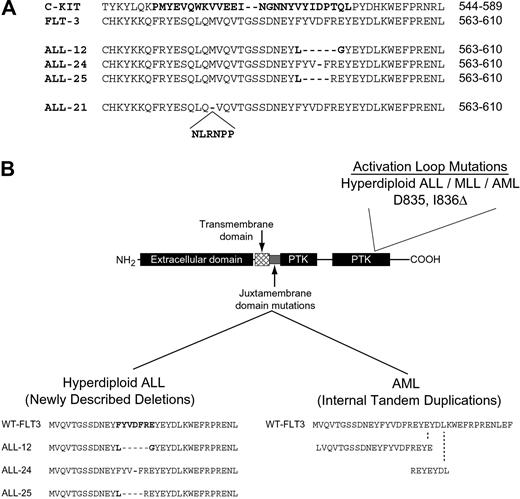

Five of the mutations identified are previously described activating mutations present in the receptor activation loop.4,6 Three of the mutations are novel and result in small in-frame deletions in the juxtamembrane region of the receptor (Figure 1A-B). One of these patients (no. 24) had a single amino acid deletion of Asp593 that was present in leukemia blasts at diagnosis and relapse but was not found in bone marrow cells taken during remission. Thus, this mutation was not an uncommon polymorphism but was acquired in the leukemia blasts. Although this type of FLT3 mutation is novel in human disease, small deletions of the 10-amino acid region of FLT3 from Tyr589 to Tyr599 have been previously shown to lead to constitutive activation.13 When we compared these mutations to those found in tyrosine kinases in other diseases, we found that similar small deletion mutations are found in the receptor tyrosine kinase c-KIT in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs; Figure 1A).14-16 Similar deletion mutations are also found in c-kit in the murine mastocytoma cell line FMA3.17 In both cases this type of mutation leads to receptor activation. Another unique mutation is a novel 15-bp insertion in the juxtamembrane region of the receptor that maintains an open reading frame. This is reminiscent of the FLT3 internal tandem duplications (FLT3-ITDs) found in AML (Figure 1B). Finally, one TEL/AML1-rearranged sample harbored a 30-bp FLT3-ITD.

FLT3 mutations found in the juxtamembrane region and activation loop in ALL and AML. (A) An alignment of the juxtamembrane regions encompassing amino acids 563-610 of FLT3 and 544-589 of c-KIT is shown. The region of mutation of c-KIT in GIST is in bold as are the 4 FLT3 mutations found in ALL samples 12, 24, 21, and 25. (B) The different FLT3 mutations found in AML and ALL are shown. Internal tandem duplications (FLT3-ITDs) in the juxtamembrane region have been described in AML.2,3 Two FLT3-ITDs are shown as examples. Deletions in the juxtamembrane region are found in ALL. Activation loop mutations are found in ALL, AML, and MLL.4,6

FLT3 mutations found in the juxtamembrane region and activation loop in ALL and AML. (A) An alignment of the juxtamembrane regions encompassing amino acids 563-610 of FLT3 and 544-589 of c-KIT is shown. The region of mutation of c-KIT in GIST is in bold as are the 4 FLT3 mutations found in ALL samples 12, 24, 21, and 25. (B) The different FLT3 mutations found in AML and ALL are shown. Internal tandem duplications (FLT3-ITDs) in the juxtamembrane region have been described in AML.2,3 Two FLT3-ITDs are shown as examples. Deletions in the juxtamembrane region are found in ALL. Activation loop mutations are found in ALL, AML, and MLL.4,6

It is of interest to note that 2 of the samples contained mutant FLT3 alleles at a frequency of less than 2% even though the blast percentage was high. Although this could possibly represent contamination, we feel that this is unlikely because we have performed more than 100 negative controls in the laboratory with no false-positive results. We feel that it is more likely to represent clonal evolution within the leukemias as has been demonstrated for FLT3 mutations in AML.18,19 Future study will determine the importance of FLT3 mutations in such cases.

These data show that FLT3 mutations are common in hyperdiploid ALL in contrast to published reports that have assessed adult ALL where FLT3 mutation is uncommon.2,4 We propose that this reflects an association between FLT3 mutations and hyperdiploid ALL or MLL, both of which are quite rare in adults. It is of interest to note that although we found multiple mutations of FLT3 in hyperdiploid ALL, we found no cases that possessed an FLT3-ITD, the most common mutation found in AML (Figure 1B). Further study will determine if this is due to different mechanisms of mutagenesis in developing myeloid as compared to lymphoid cells or if the distinct FLT3 mutants have unique signaling properties.

An important question is whether or not the presence of FLT3 mutations in ALL has prognostic significance. A definitive answer to this question will require larger studies of MLL and hyperdiploid ALL samples, but it is important to note that 3 of the 16 patients with ALL that relapsed harbored FLT3 mutations at diagnosis. The presence of FLT3 mutations in these cases suggests that FLT3 inhibition may represent a therapeutic opportunity in at least a subset of patients with relapsed ALL.

The data presented here provide further evidence that genomic analysis of cancer cells will uncover important biologic subsets. Even though FLT3 mutations were considered rare in lymphoblastic leukemias, microarray analysis revealed high-level FLT3 expression prompting DNA sequencing, which uncovered 2 subtypes of ALL that frequently contain FLT3 mutations. Thus there appears to be an association between high-level expression of FLT3 and the presence of activation loop mutations. This has also been demonstrated recently for AML where all samples with activation loop mutations have high-level expression.20 Further study will determine the molecular underpinnings of this association. These data in conjunction with our previous finding in MLL provide strong support for the development of clinical trials that will test the efficacy of FLT3 inhibitors in childhood ALL. Furthermore, the presence of FLT3 mutations will prompt a more systematic analysis of tyrosine kinase mutations in childhood ALL.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, December 11, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2441.

Supported by National Cancer Institute Grants CA92551 and CA68484, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and the William Lawrence and Blanche Hughes Fund of the California Community Foundation. S.A.A. is a recipient of a Damon Runyon-Lilly Clinical Investigator Award.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We wish to thank Susanna Hamilton, Mark Hansen, and Sigitas Verselis of the Shannon McCormack Advanced Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute for carrying out the FLT3 mutation analysis. We also thank Virginia Dalton and Angelo Cardoso for help with sample acquisition.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal