Abstract

A novel oncogenic mutation (FIP1L1-PDGFRA), which results in a constitutively activated platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α (PDGFRA), has been invariably associated with a primary eosinophilic disorder. The current study examines both the prevalence and the associated clinicopathologic features of this mutation in a cohort of 89 adult patients presenting with an absolute eosinophil count (AEC) of higher than 1.5 × 109/L. A fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)–based strategy was used to detect FIP1L1-PDGFRA in bone marrow cells. None of 8 patients with reactive eosinophilia displayed the abnormality, whereas the incidence of FIP1L1-PDGFRA in the remaining 81 patients with primary eosinophilia was 14% (11 patients). None (0%) of 57 patients with the hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) but 10 (56%) of 19 patients with systemic mast cell disease associated with eosinophilia (SMCD-eos) carried the specific mutation. The bone marrow mast cell infiltration pattern in FIP1L1-PDGFRA+ SMCD-eos was distinctly diffuse with loose tumoral aggregates. Treatment with low-dose imatinib (100 mg/d) produced complete and durable responses in all 8 FIP1L1-PDGFRA+ cases treated. In contrast, only 40% partial response rate was seen in 10 HES cases. FIP1L1-PDGFRA is a relatively infrequent but treatment-relevant mutation in primary eosinophilia that is indicative of an underlying systemic mastocytosis.

Introduction

Blood eosinophilia is diagnostically nonspecific and may accompany many unrelated medical disorders.1 The process is considered reactive when associated with an underlying parasitic infestation, atopic disorder, drug reaction, connective tissue disease, or a nonmyeloid malignant disorder such as Hodgkin lymphoma. “Nonreactive” eosinophilia is considered “clonal” in the presence of either a cytogenetic abnormality or bone marrow morphologic evidence of a myeloid disorder such as acute or chronic myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, or systemic mast cell disease (SMCD). A small subset of cases in which both reactive and clonal causes of eosinophilia are excluded may be classified as idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) if peripheral blood eosinophilia (> 1.5 × 109/L) is documented to persist for at least 6 months and if there is eosinophil-mediated damage to end organs such as lungs, heart, or nervous system.

In a series of recent reports, imatinib mesylate (Gleevec), a small molecule that selectively inhibits the Abelson (Abl), Bcr/Abl, Kit, and platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α (PDGFRA) and -β (PDGFRB) tyrosine kinases, has been shown to have a dramatic, albeit variable, efficacy for the treatment of a subgroup of patients with HES or clonal eosinophilia including SMCD.2-6 More recently, a novel tyrosine kinase generated from the fusion of the Fip1-like 1 (FIP1L1) gene to the PDGFRA gene (FIP1L1-PDGFRA) was identified in 9 (56%) of 16 patients deemed to have HES.3 Eleven of these patients were treated with imatinib mesylate (imatinib) and of the 9 patients that achieved a complete response for at least 3 months, 5 carried the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion. The molecular target for imatinib was not identified in the remaining 4 responding patients. A subsequent report involving a small number of patients suggested that a subset of imatinib-responsive patients diagnosed with HES cases are characterized by bone marrow infiltration by morphologically and immunophenotypically abnormal mast cells in association with elevated serum tryptase levels, splenomegaly, and absence of the c-kit D816V mutation.7 Most, if not all of, such cases, referred to as the “myeloproliferative” variant of HES by some7 and FIP1L1-PDGFRA+ SMCD-eos (SMCD associated with eosinophilia) by others,8 carry the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion and achieve a complete and durable remission with low doses of imatinib (100 mg/d).

These observations constitute a seminal advance in the association of a novel oncogenic mutation with both prominent eosinophilia and treatment response to imatinib as well as underscore the molecular and pathologic diversity in eosinophilic disorders. In the current study, the technique of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was applied to estimate the prevalence of FIP1L1-PDGFRA in an unselected, consecutive cohort of 89 adult patients with moderate to severe eosinophilia (eosinophil count > 1.5 × 109/L). We also provide a detailed account of both the clinicopathologic features and treatment information for FIP1L1-PDGFRA+ disease (11 patients) and imatinib therapy in such patients (26 cases).

Patients, materials, and methods

We conducted a single-institution, combined prospective (45 cases) and retrospective (44 cases) study of 89 consecutively presenting adult patients with moderate to severe peripheral blood eosinophilia (> 1.5 × 109/L). The patients who were studied retrospectively were identified by querying the Mayo Clinic electronic database for the diagnostic string “eosinophilia,” “hypereosinophilic syndrome,” “eosinophilic leukemia,” or “mast cell disease.” No other selection or exclusion criteria were imposed for the purposes of this study. After a central re-review of bone marrow histology as well as pertinent laboratory and clinical data, patients were classified as having either “HES,”1 “SMCD-eos,”9 or “clonal eosinophilia/chronic eosinophilic leukemia”1 based on criteria that have been promoted by the World Health Organization (WHO) and reinforced in recent general reviews (Tables 3-4).1,9 Patients for whom a clearly plausible underlying cause for eosinophilia was identified, including parasitic infestations or an associated nonmyeloid malignancy such as Hodgkin lymphoma or renal cell carcinoma, were classified as having “reactive” eosinophilia. In 82 (92%) of the 89 patients, including all the patients treated with imatinib mesylate, presence of previously known drug targets, including the Philadelphia chromosome or its molecular equivalent (bcr/abl),10 and t(5;12)(q33;p13)11 was excluded by either karyotype or FISH. Only 3 of the current cohort of 11 patients with FIP1L1-PDGFRA+ disease and 17 in the entire current study population (N = 89) have previously been reported.4,5,8

Criteria for the operational classification of patients with eosinophilia

Persistent eosinophilia (at least 1.5 × 109/L) for at least 6 months associated with evidence of end-organ disease |

| Nonidiopathic |

| Clonal eosinophilia |

| Identification of a cytogenetic or molecular abnormality* |

| Bone marrow morphologic evidence of a myeloid disorder† |

| Reactive eosinophilia |

| Parasites, atopy, drug reaction, connective tissue disease, nonmyeloid malignancy (eg, Hodgkin lymphoma, etc) |

| Idiopathic |

| Hypereosinophilic syndrome |

Persistent eosinophilia (at least 1.5 × 109/L) for at least 6 months associated with evidence of end-organ disease |

| Nonidiopathic |

| Clonal eosinophilia |

| Identification of a cytogenetic or molecular abnormality* |

| Bone marrow morphologic evidence of a myeloid disorder† |

| Reactive eosinophilia |

| Parasites, atopy, drug reaction, connective tissue disease, nonmyeloid malignancy (eg, Hodgkin lymphoma, etc) |

| Idiopathic |

| Hypereosinophilic syndrome |

Eg, acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with t(16;16), 8p11 myeloproliferative syndromes (EMS), FIPIL1-PDGFRA fusion, etc. No distinction is made as to whether or not the cytogenetic or molecular abnormality conclusively establishes the eosinophils to be derived from the neoplastic clone.

Based on French-American-British (FAB)/WHO criteria; includes eosinophilia associated-myelodysplastic syndrome, -systemic mast cell disease, etc.

WHO criteria for systemic mast cell disease

Major |

| Multifocal dense infiltrates of mast cells (MCs; more than 15 MCs aggregating) detected in sections of bone marrow (BM) and/or of other extracutaneous organ(s) by tryptase immunohistochemistry or other stains |

| Minor |

| In MCs, infiltrates detected in sections of BM or other extracutaneous organs, more than 25% of MCs are spindle-shaped or, in BM smears, atypical MCs comprise more than 25% of all MC |

| Detection of a c-kit point mutation at codon 816 in BM or blood or other extracutaneous organ(s) |

| Kit+ MCs in M or blood or other extracutaneous organ(s) coexpress CD2 and/or CD25 |

| Serum total tryptase concentration persistently greater than 20 ng/mL |

Major |

| Multifocal dense infiltrates of mast cells (MCs; more than 15 MCs aggregating) detected in sections of bone marrow (BM) and/or of other extracutaneous organ(s) by tryptase immunohistochemistry or other stains |

| Minor |

| In MCs, infiltrates detected in sections of BM or other extracutaneous organs, more than 25% of MCs are spindle-shaped or, in BM smears, atypical MCs comprise more than 25% of all MC |

| Detection of a c-kit point mutation at codon 816 in BM or blood or other extracutaneous organ(s) |

| Kit+ MCs in M or blood or other extracutaneous organ(s) coexpress CD2 and/or CD25 |

| Serum total tryptase concentration persistently greater than 20 ng/mL |

If 1 major and 1 minor or 3 minor criteria are fulfilled then the diagnosis of systemic mastocytosis is established.

For the purposes of the current study, complete response (CR) to treatment comprised normalization of eosinophil count lasting for at least one month accompanied by complete resolution of clinical symptoms (eg, pruritus, bone pain, other mast cell mediator symptoms) and signs (eg, splenomegaly, cutaneous manifestations, pulmonary infiltrates, leukocytosis, cytopenia). A partial response (PR) comprised a more than 50% reduction in eosinophil count that has lasted for at least one month. It is to be noted that CR and PR as defined in the current paper did not require the demonstration of either a complete bone marrow histologic response (ie, reduction in cellularity, resolution of myelofibrosis if present, and numeric normalization of both bone marrow eosinophilia and mastocytosis) or a complete molecular response by FISH. However, information in the latter 2 aspects (ie, histologic and molecular response) was provided when available. Also, our definition, for now, did not require reversal of chronic myocardial damage from eosinophilic heart disease.

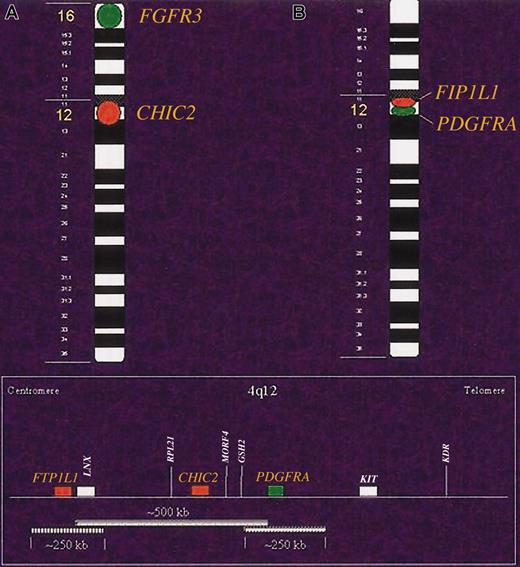

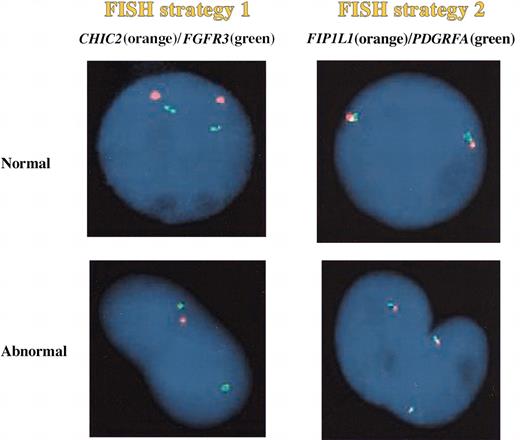

Two FISH-based strategies were pursued using whole bone marrow aspirate smears to detect deletion of the CHIC2 locus at 4q12 or excision of the CHIC2 locus at 4q12 and its translocation to another place in the karyotype (Figures 1, 2, 3). Both of these cytogenetic mechanisms result in fusion of the FIP1L1 and PDGFRA at 4q12. The first strategy used a modification of the one-color interphase FISH approach, which we described previously.8 Briefly, this method uses a 2-color interphase FISH approach with probes covering the CHIC2 locus direct-labeled with Spectrum Orange and a control probe covering the FGFR3 locus at 4p16.3 that was labeled in Spectrum Green (Figure 1). Deletion of one of the CHIC2 alleles results in 1 orange and 2 green signals in interphase nuclei (Figure 2).

Probe schematic. Two strategies were used to detect FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion at chromosome 4q12. The first strategy used a 2-color FISH approach with probes covering the CHIC2 locus at 4q12 that is direct-labeled with Spectrum Orange and a control probe covering the FGFR3 locus at 4p16.3 that was labeled in Spectrum Green (A). The second strategy used a break-apart FISH approach with 2 probes that both partially cover the CHIC2 locus and completely cover either the flanking FIP1L1 (labeled with Spectrum Orange) or PDGFRA (labeled with Spectrum Green) loci (B).

Probe schematic. Two strategies were used to detect FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion at chromosome 4q12. The first strategy used a 2-color FISH approach with probes covering the CHIC2 locus at 4q12 that is direct-labeled with Spectrum Orange and a control probe covering the FGFR3 locus at 4p16.3 that was labeled in Spectrum Green (A). The second strategy used a break-apart FISH approach with 2 probes that both partially cover the CHIC2 locus and completely cover either the flanking FIP1L1 (labeled with Spectrum Orange) or PDGFRA (labeled with Spectrum Green) loci (B).

Interphase FISH. Deletion of 1 of the CHIC2 alleles results in 1 orange and 2 green signals in interphase nuclei (FISH strategy 1). However, this 2-color FISH strategy using CHIC2/FGFR3 probe set would appear normal if CHIC2 was translocated rather than deleted. In such cases, the abnormality will be detected by the second FISH strategy where the insertional translocation involving excision of the CHIC2 locus results in a FISH signal pattern of 3 fusions using the FIP1L1/PDGFRA probe set.

Interphase FISH. Deletion of 1 of the CHIC2 alleles results in 1 orange and 2 green signals in interphase nuclei (FISH strategy 1). However, this 2-color FISH strategy using CHIC2/FGFR3 probe set would appear normal if CHIC2 was translocated rather than deleted. In such cases, the abnormality will be detected by the second FISH strategy where the insertional translocation involving excision of the CHIC2 locus results in a FISH signal pattern of 3 fusions using the FIP1L1/PDGFRA probe set.

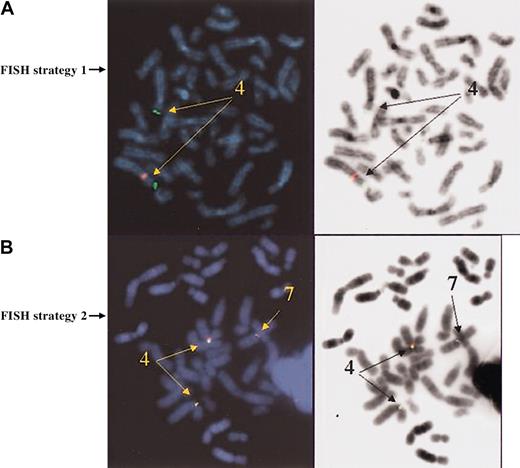

Metaphase FISH. Signal patterns of abnormal results from either deletion (A) or translocation (B) of CHIC2 by metaphase FISH. In both panels, 7 indicates chromosome 7; 4, chromosome 4.

Metaphase FISH. Signal patterns of abnormal results from either deletion (A) or translocation (B) of CHIC2 by metaphase FISH. In both panels, 7 indicates chromosome 7; 4, chromosome 4.

The second strategy used a break-apart FISH approach with probes that partially cover the CHIC2 locus and completely cover either the flanking FIP1L1 (labeled with Spectrum Orange) or PDGFRA (labeled with Spectrum Green) loci (Figure 1). This 2-color break-apart FISH strategy was designed to detect excision of CHIC2 at 4q12 and translocation to another chromosomal site with consequent fusion of FIP1L1 and PDGFRA at 4q12. An insertional translocation involving excision of the CHIC2 locus results in a FISH signal pattern of 3 fusions using the FIP1L1/PDGFRA probe set (Figure 2). In contrast, the 2-color FISH strategy using CHIC2/FGFR3 probe set would appear normal in this situation. Bone marrow specimens were processed for FISH using standard methods, and a total of 200 interphase nuclei were independently scored by 2 individuals in a blinded fashion. These FISH methodologies were validated in 30 healthy controls. Based on analysis of results from the healthy controls, the normal cutoff for CHIC2 deletion is 4.5% and 3.0% for translocations of CHIC2.

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells and/or bone marrow mononuclear cells from all 19 SMCD-eos patients and screened for the activating c-kit Asp816Val (D816V) mutation by direct sequencing of exon 17 as previously described.12 Bone marrow mast cell immunophenotyping was performed in cases where an adequate sample was available (Table 2) to assess cell surface expression of the following antigens: CD117, CD34, CD69, CD2, CD25, CD35, and CD71.13

Clinical and laboratory details of the 10 SMCD-eos patients and 1 UMPD with the CHIC2 deletion

Patient no. . | Age, y . | Clinical features . | Initial clinical diagnosis* . | Pathologic diagnosis . | Serum tryptase, ng/mL† . | Marrow histology . | Mast cell phenotype‡ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 46§ | Urticaria pigmentosa, pruritus, diarrhea, weight loss, splenomegaly | SMCD | SMCD | 144 | Paratrabecular/perivascular and loose interstitial aggregates of dysplastic mast cells; reticulin fibrosis | CD117+/CD25 |

| 2 | 30§ | Bone pain, headache, leukocytosis, cytopenia, splenomegaly | UMPD | SMCD | ND | Paratrabecular/perivascular and loose interstitial aggregates of dysplastic mast cells; reticulin fibrosis | CD117+/CD25 |

| 3 | 26§ | Endocardial fibrosis, ventricular thrombosis, valvular heart disease, congestive hear failure | SMCD | SMCD | ND | Perivascular and loose interstitial aggregates of dysplastic mast cells, reticulin fibrosis | ND |

| 4 | 45§ | Bone pain, weight loss, constitutional symptoms, massive splenomegaly, severe cytopenia | HES | UMPD | ND | No increase in mast cells, reticulin fibrosis, panhyperplasia | ND |

| 5 | 72 | Diarrhea, pruritus, severe weight loss, fat malabsorption | SMCD | SMCD | 56 | Interstitial and focal loose aggregates of dysplastic mast cells | CD117+/CD25 |

| 6 | 49 | Recurrent syncope, constitutional symptoms, hepatosplenomegaly | HES | SMCD | 31 | Interstitial loose aggregates of dysplastic mast cells | CD117+/CD25 |

| 7 | 51 | Congestive heart failure, splenomegaly | HES | SMCD | 32.1 | Interstitial loose aggregates of dysplastic mast cells | CD117+/CD25 |

| 8 | 50 | Severe headaches, peripheral neuropathy, stroke | HES | SMCD | ND | Interstitial loose aggregates of dysplastic mast cells | ND |

| 9 | 40 | Cardiomyopathy, pericardial effusion, multiple cerebral infarcts | CEL | SMCD | ND | Interstitial loose aggregates of dysplastic mast cells | ND |

| 10 | 40 | Cardiomyopathy | HES | SMCD | ND | Interstitial loose aggregates of dysplastic mast cells | ND |

| 11 | 26 | Pruritus, splenomegaly | HES | SMCD | 51 | Interstitial loose aggregates of dysplastic mast cells | ND |

Patient no. . | Age, y . | Clinical features . | Initial clinical diagnosis* . | Pathologic diagnosis . | Serum tryptase, ng/mL† . | Marrow histology . | Mast cell phenotype‡ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 46§ | Urticaria pigmentosa, pruritus, diarrhea, weight loss, splenomegaly | SMCD | SMCD | 144 | Paratrabecular/perivascular and loose interstitial aggregates of dysplastic mast cells; reticulin fibrosis | CD117+/CD25 |

| 2 | 30§ | Bone pain, headache, leukocytosis, cytopenia, splenomegaly | UMPD | SMCD | ND | Paratrabecular/perivascular and loose interstitial aggregates of dysplastic mast cells; reticulin fibrosis | CD117+/CD25 |

| 3 | 26§ | Endocardial fibrosis, ventricular thrombosis, valvular heart disease, congestive hear failure | SMCD | SMCD | ND | Perivascular and loose interstitial aggregates of dysplastic mast cells, reticulin fibrosis | ND |

| 4 | 45§ | Bone pain, weight loss, constitutional symptoms, massive splenomegaly, severe cytopenia | HES | UMPD | ND | No increase in mast cells, reticulin fibrosis, panhyperplasia | ND |

| 5 | 72 | Diarrhea, pruritus, severe weight loss, fat malabsorption | SMCD | SMCD | 56 | Interstitial and focal loose aggregates of dysplastic mast cells | CD117+/CD25 |

| 6 | 49 | Recurrent syncope, constitutional symptoms, hepatosplenomegaly | HES | SMCD | 31 | Interstitial loose aggregates of dysplastic mast cells | CD117+/CD25 |

| 7 | 51 | Congestive heart failure, splenomegaly | HES | SMCD | 32.1 | Interstitial loose aggregates of dysplastic mast cells | CD117+/CD25 |

| 8 | 50 | Severe headaches, peripheral neuropathy, stroke | HES | SMCD | ND | Interstitial loose aggregates of dysplastic mast cells | ND |

| 9 | 40 | Cardiomyopathy, pericardial effusion, multiple cerebral infarcts | CEL | SMCD | ND | Interstitial loose aggregates of dysplastic mast cells | ND |

| 10 | 40 | Cardiomyopathy | HES | SMCD | ND | Interstitial loose aggregates of dysplastic mast cells | ND |

| 11 | 26 | Pruritus, splenomegaly | HES | SMCD | 51 | Interstitial loose aggregates of dysplastic mast cells | ND |

All patients were male.

SMCD indicates systemic mast cell disease; UMPD, unclassified myeloproliferative disorder; ND, not done; HES, hypereosinophilic syndrome; and CEL, chronic eosinophilic leukemia.

Initial diagnosis refers to either external or internal referral diagnosis. World Health Organization (WHO) criteria were used to make WHO diagnosis. All patients had prominent peripheral blood and bone marrow eosinophilia and neither the bcr/abl (10 patients studied) nor the D816V c-kit mutation (10 patients studied) was detected. Bone marrow mast cell infiltration pattern was assessed with the aid of both tryptase and Kit (CD117) staining. Karyotype analysis was normal in all cases but the one with chronic eosinophilic leukemia (CEL).

Normal serum tryptase is < 11.5 ng/mL. It should be noted that some of the values were obtained in the presence of corticosteroid therapy.

Normal mast cell immunophenotype profile is CD117+/CD25-/CD2-.

Both initial and WHO diagnosis made prior to the discovery of the FIPIL1-PDGFRA mutation (ie, diagnosis made between 1994 and 2002).

The accrual of patient data and collection of biologic specimens was approved by Mayo Clinic's institutional review board.

Results

Overall and disease-specific incidence and bone marrow histologic correlates of CHIC2 deletion/translocation: a surrogate for FIP1L1-PDGFRA

Of the total 89 patients, the specific diagnosis after a comprehensive evaluation of all available data including bone marrow histology was HES for 57 patients (64%), SMCD-eos for 19 patients (21%), clonal eosinophilia for 5 patients (6%), and reactive eosinophilia for 8 patients (9%; Table 1). All HES cases fulfilled the WHO diagnostic criteria,9 were subjected to an extensive workup for parasitic infection, and showed no evidence of abnormal mast cell clusters in their bone marrow by hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining. In addition, bone marrow tryptase immunostaining was performed in 43 of the 57 patients with HES; 34 cases were completely normal without any increase in mast cell number, 6 cases showed a slight increase in morphologically normal mast cells, and 3 cases showed a moderate increase in the number of mast cells where the majority were again morphologically normal and without any evidence of loose aggregates or clusters. Cytogenetic studies were performed in 47 of the 57 HES cases and clonal lesions were uniformly absent with the exception of the loss of a Y chromosome noted in 4 patients. Furthermore, 22 patients with HES were screened for clonal rearrangement of the T-cell receptor antigen gene and only 2 displayed a positive result.

Clinical and laboratory features of 89 consecutive adult patients with moderate to severe eosinophilia

. | . | SMCD-eos . | . | Clonal eosinophilia . | . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study population . | HES* . | Pos . | Neg . | Pos . | Neg . | Reactive eosinophilia* . | ||

| No. of patients | 57 | 10 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 8 | ||

| Age, y, median (range) | 52 (18-83) | 43 (26-72) | 78 (53-85) | 46 (NA) | 60 (20-88) | 50.5 (30-80) | ||

| No. of men (%) | 37 (65) | 10 (100) | 3 (33) | 1 (100) | 4 (100) | 4 (50) | ||

| Eosinophil count, × 109/L, median (range) | 4.2 (1.5-126.8) | 10.3 (2.1-51.3) | 6.1 (2.4-27.7) | 2.1 (NA) | 4.9 (1.7-11.9) | 3.3 (2.0-36.7) | ||

| Organ involvement (% of patients affected) | Skin (40) | Cardiac (30) | Gut (67) | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Lung (42) | Gut (30) | Liver/spleen (67) | ||||||

| Gut (21) | Skin (30) | Skin (44) | ||||||

| Cardiac (10) | Liver/spleen (30) | Lung (11) | ||||||

| Neurologic (8) | Neurologic (30) | |||||||

| Thrombosis (8) | Other (30) | |||||||

| Other (14) | NA | |||||||

| BM mast cell, %, median (range) | NA | 10 (5-30) | 25 (5-70) | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Predominant BM mast cell pattern (no.) | NA | Tight (3) | Tight (7) | NA | NA | |||

| Loose (7) | Loose (2) | |||||||

| No. of patients with abnormal karyotype (total no. studied) | 0 (48) | 2 (9) trisomy 8 + X | 0 (9) | 0 (1) | 4 (4) | 0 (7) | ||

| Imatinib therapy, no. | 10 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 0 | ||

| OR, no. (%) | 4 (40) | 7 (100) | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | ||

| CR, no. (%) | 0 | 7 (100) | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | ||

| PR, no. (%) | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

. | . | SMCD-eos . | . | Clonal eosinophilia . | . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study population . | HES* . | Pos . | Neg . | Pos . | Neg . | Reactive eosinophilia* . | ||

| No. of patients | 57 | 10 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 8 | ||

| Age, y, median (range) | 52 (18-83) | 43 (26-72) | 78 (53-85) | 46 (NA) | 60 (20-88) | 50.5 (30-80) | ||

| No. of men (%) | 37 (65) | 10 (100) | 3 (33) | 1 (100) | 4 (100) | 4 (50) | ||

| Eosinophil count, × 109/L, median (range) | 4.2 (1.5-126.8) | 10.3 (2.1-51.3) | 6.1 (2.4-27.7) | 2.1 (NA) | 4.9 (1.7-11.9) | 3.3 (2.0-36.7) | ||

| Organ involvement (% of patients affected) | Skin (40) | Cardiac (30) | Gut (67) | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Lung (42) | Gut (30) | Liver/spleen (67) | ||||||

| Gut (21) | Skin (30) | Skin (44) | ||||||

| Cardiac (10) | Liver/spleen (30) | Lung (11) | ||||||

| Neurologic (8) | Neurologic (30) | |||||||

| Thrombosis (8) | Other (30) | |||||||

| Other (14) | NA | |||||||

| BM mast cell, %, median (range) | NA | 10 (5-30) | 25 (5-70) | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Predominant BM mast cell pattern (no.) | NA | Tight (3) | Tight (7) | NA | NA | |||

| Loose (7) | Loose (2) | |||||||

| No. of patients with abnormal karyotype (total no. studied) | 0 (48) | 2 (9) trisomy 8 + X | 0 (9) | 0 (1) | 4 (4) | 0 (7) | ||

| Imatinib therapy, no. | 10 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 0 | ||

| OR, no. (%) | 4 (40) | 7 (100) | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | ||

| CR, no. (%) | 0 | 7 (100) | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | ||

| PR, no. (%) | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

The study population was 49 individuals. HES indicates hypereosinophilic syndrome; SMCD-eos, eosinophilia-associated systemic mast cell disease; Neg, negative CHIC2 deletion; Pos, positive CHIC2 deletion; NA, not applicable; BM, bone marrow; OR, overall response; CR, complete response; and PR, partial response.

CHIC2 deletions were all negative for this group.

Of the 8 patients with reactive eosinophilia, 2 had strongyloidiasis, 1 had Hodgkin lymphoma, 1 had angioblastic T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, 1 had Sézary syndrome, 1 had drugrelated Steven-Johnson syndrome, 1 had metastatic renal cell carcinoma, and the eighth patient had a systemic illness that was characterized by skin rash, fever, and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura that was accompanied by seizures and renal failure. This latter patient was documented to have a normal eosinophil count a few days before the onset of her illness, and appropriate management of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) and antibiotic therapy for possible streptococcus-related skin disease was later accompanied by resolution of her severe blood eosinophilia.

Eleven (12%) of the 89 patients were found to have either a deletion (10 patients) or a translocation to chromosome 7q11.2 (1 patient) of the CHIC2 locus on chromosome 4q12 (Tables 1-2). The corresponding incidence in the 81 patients with primary eosinophilia was 14%. In a previous report, we used reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to confirm that CHIC2 deletion represented FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion.8 Among the 11 identified cases of CHIC2 deletion/translocation, 10 had SMCD-eos (ie, 56% of all SMCD-eos cases) and 1 had clonal eosinophilia. Classification of the latter patient as clonal eosinophilia was based on both peripheral blood smear findings and bone marrow histology. The blood smear was leukoerythroblastic with 6% blasts, 11% myelocytes, 3% metamyelocytes, and 1% nucleated red blood cells. The bone marrow was markedly hypercellular with a myeloproliferative picture and increased reticulin fibrosis but lacked abnormal mast cell infiltration by tryptase stain. Cytogenetic studies were normal. None (0%) of the 57 cases with HES displayed CHIC2 deletion (Table 1). However, 7 of the 11 CHIC2-deleted/translocated patients were initially diagnosed with HES based on clinical information alone, and only after review of tryptase-stained bone marrow sections, mast cell immunophenotyping, and serum tryptase level were they reclassified as having SMCD based on the WHO diagnostic criteria (Tables 2, 3, 4).9 In this regard, it is underscored that disease reclassification required bone marrow histologic confirmation by tryptase staining in all instances.

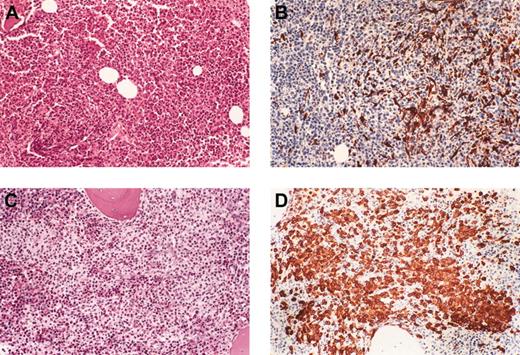

Tryptase immunostaining of bone marrow sections comparing the SMCD-eos patients with and without the CHIC2 deletion or translocation revealed interesting contrasts (Table 1; Figure 4). For all patients in the former group (FIP1L1-PDGFRA+ SMCD-eos), the general tendency of atypical mast cells infiltrating the bone marrow was to form loose, ill-defined aggregates that were very difficult if not impossible to appreciate on H&E-stained sections. Only on tryptase-immunostained sections, particularly at low power, were the loose aggregates brought out in relief. The typical “tumoral” clusters or sheets of mast cells that are commonly observed in the bone marrow of SMCD patients without the CHIC2 deletion or translocation (both with and without eosinophilia) were present in only 3 of the 10 FIP1L1-PDGFRA+ SMCD-eos patients. Careful examination of serial bone marrow sections for the majority of patients in the latter group revealed that overt mast cell clusters were relatively rare but smaller clusters composed of 10 to 30 cells can be discerned in most cases.

Differences in the histologic pattern of bone marrow mast cell infiltration in SMCD-eos patients with and without FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion. Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E)–stained (A,C) and tryptase-immunostained (B,D) bone marrow biopsy tissue showing the ill-defined, loose aggregates of atypical mast cells associated with intense eosinophilia in cases with FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion (A-B). Typical well-defined clusters of mast cells are rare and generally small (10-30 cells), and bone marrow mast cell infiltration may be difficult to recognize unless a tryptase immunostain is done for these patients. In contrast, patients without FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion generally exhibit large, well-defined perivascular and/or peritrabecular clusters or diffuse infiltration of atypical mast cells associated with intense eosinophilia (C-D). Bone marrow mast cell infiltration is easily recognized on H&E-stained sections for these patients. Images were obtained using a Leitz Orthoplan microscope (Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with 160 ×/0.4 objective lenses (Leitz, Wetzlar, Germany).

Differences in the histologic pattern of bone marrow mast cell infiltration in SMCD-eos patients with and without FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion. Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E)–stained (A,C) and tryptase-immunostained (B,D) bone marrow biopsy tissue showing the ill-defined, loose aggregates of atypical mast cells associated with intense eosinophilia in cases with FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion (A-B). Typical well-defined clusters of mast cells are rare and generally small (10-30 cells), and bone marrow mast cell infiltration may be difficult to recognize unless a tryptase immunostain is done for these patients. In contrast, patients without FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion generally exhibit large, well-defined perivascular and/or peritrabecular clusters or diffuse infiltration of atypical mast cells associated with intense eosinophilia (C-D). Bone marrow mast cell infiltration is easily recognized on H&E-stained sections for these patients. Images were obtained using a Leitz Orthoplan microscope (Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with 160 ×/0.4 objective lenses (Leitz, Wetzlar, Germany).

Additional supporting evidence for the diagnosis of SMCD included the demonstration of a uniformly aberrant mast cell immunophenotype (CD117+/CD25+) in 5 of the 10 CHIC2-deleted SMCD-eos patients (Table 2). Four of these 5 patients also had a significant elevation of the serum tryptase level: 144, 56, 32.1, and 31 ng/mL (normal tryptase level is < 11.5 ng/mL; Table 2). One additional CHIC2-deleted SMCD-eos patient for whom mast cell immunophenotyping was not performed also had exhibited an elevated serum tryptase level (51 ng/mL).

All 19 SMCD-eos patients (10 with and 9 without CHIC2 deletion) were screened for the c-kit D816V mutation. While none of the patients with the CHIC2 deletion had this mutation, 3 of 9 patients without this deletion (33%) carried the c-kit D816V mutation.

Clinical manifestations in CHIC2-deleted and -nondeleted patients

As outlined in Table 2, about half of the CHIC2-deleted patients with SMCD-eos displayed clinical features that are characteristic of systemic mastocytosis including urticaria pigmentosa, pruritus, diarrhea, severe weight loss from malabsorption, bone pain, headaches, constitutional symptoms, organomegaly, and cytopenias. However, some of these patients also displayed symptoms and signs that are characteristic of HES including eosinophilic cardiac and neurologic disease (Tables 1-2). The latter clinical manifestations were interestingly infrequent in SMCD-eos cases without CHIC2 deletion (Table 1). Also interesting was the fact that all CHIC2-deleted SMCD patients were males, whereas 6 of the 9 SMCD cases without CHIC2 deletions were females.

Treatment experience with imatinib mesylate

A total of 26 patients, including 8 cases with CHIC2 deletion, were treated and/or maintained with imatinib at a daily dose of 100 mg/d or less (Tables 1 and 5). All 8 patients with CHIC2 deletion achieved CR, with resolution of disease symptoms and signs and normalization of the eosinophil count (7 with SMCD-eos and 1 with clonal eosinophilia). A repeat bone marrow biopsy after 3 to 6 months of therapy was done in 5 of the 8 patients and showed a complete histologic as well as molecular response in all of them (Table 5). The treatment details of these 8 patients as well as 3 others with CHIC2 deletion that were not treated with imatinib are given in Table 5. It is to be noted that all 8 imatinib-treated patients required low-dose imatinib (100 mg/d) to attain and/or maintain CR. The single patient who had translocation of the CHIC2 locus did not receive imatinib therapy but achieved a durable CR after treatment with interferon-α.

Treatment response data for 10 SMCD-eos patients and 1 UMPD patient (M/45) with the CHIC2 deletion/translocation

. | Patient 1 . | Patient 2 . | Patient 3 . | Patient 4 . | Patient 5 . | Patient 6 . | Patient 7 . | Patient 8 . | Patient 9 . | Patient 10 . | Patient 11 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 46 | 30 | 26 | 45 | 72 | 49 | 51 | 50 | 40 | 40 | 26 |

| Diagnosis date | 5/31/2001 | 6/12/2001 | 1/6/1994 | 4/29/02 | 2/29/2003 | 10/6/2003 | 8/5/2003 | 1/18/1995 | 10/1/1994 | 5/6/1992 | 4/10/2003 |

| Treatment date | 5/28/2002 | 8/13/2001 | 1/20/1994 | 5/2/2002 | 3/4/2003 | 10/15/2003 | 8/12/2003 | 6/1/2001 | 12/2/1997 | 4/20/1994 | 5/5/2003 |

| Follow-up, mo | 18+ | 28+ | 118+ | 17+ | 9+ | 5+ | 4+ | 30+ | 72+ | 115+ | 7+ |

| Current status | Alive | Alive | Alive | Alive | Alive | Alive | Alive | Alive | Alive | Dead | Alive |

| Prior treatment | None | HU, IFN | None | None | HU | Pred | HU, Pred | Pred, HU, IFN | Pred, HU, CsA, IFN | None | None |

| Imatinib mesylate induction/maintenance, mg/d or mg/BIW | 100/100 | 100/100 | NA | 100/100 | 100/100 | 100/100 | 100/100 | 100/100 | NA | NA | 100/100 |

| Other induction treatment | NA | NA | IFN 9MU TIW none | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2-CdA (0.09 mg/kg/d × 7d/cycle) | IFN 5MU TIW + Pred 60mg/kg/d IFN 2MU TIW | NA |

| Treatment response | CR | CR | CR | CR | CR | CR | CR | CR | PR | CR | CR |

| Therapy status | |||||||||||

| Hgb level, g/dL | |||||||||||

| Before | 12.1 | 9.2 | 14.6 | 7.7 | 13.9 | 14 | 14.4 | 11.0 | 11.1 | 12.7 | 11.6 |

| After | 15.1 | 15.3 | 15.7 | 16.5 | 15.3 | 15.2 | 14.7 | 13.9 | 11.6 | 13.8 | 14.2 |

| WBC count, × 109/L | |||||||||||

| Before | 14.5 | 69.8 | 12.2 | 14.3 | 15.2 | 24.1 | 7.2 | 18.3 | 94.1 | 38.8 | 18.7 |

| After | 4.9 | 6.1 | 7.0 | 6.9 | 6.6 | 6.3 | 6.6 | 7.3 | 9.4 | 4.0 | 6.6 |

| AEC count, × 109/L | |||||||||||

| Before | 10.7 | 16.1 | 4.6 | 2.2 | 10.2 | 12.2 | 2.1 | 15.0 | 81.9 | 14.0 | 10.1 |

| After | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 4.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Platelet count, × 109/L | |||||||||||

| Before | 118 | 31 | 178 | 53 | 213 | 206 | 143 | 135 | 112 | 81 | 151 |

| After | 169 | 179 | 134 | 117 | 227 | 271 | 171 | 245 | 141 | 132 | 232 |

| CHIC2 deletion, % abnormal nuclei | |||||||||||

| Before | 61.0 | 58.0 | 47.0 | 87.5 | 76.0 | 45 | 48.0 | 42.0 | 64.0 | 80.0 | 74.0 |

| After | 0.0 | 1.5 | ND | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

. | Patient 1 . | Patient 2 . | Patient 3 . | Patient 4 . | Patient 5 . | Patient 6 . | Patient 7 . | Patient 8 . | Patient 9 . | Patient 10 . | Patient 11 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 46 | 30 | 26 | 45 | 72 | 49 | 51 | 50 | 40 | 40 | 26 |

| Diagnosis date | 5/31/2001 | 6/12/2001 | 1/6/1994 | 4/29/02 | 2/29/2003 | 10/6/2003 | 8/5/2003 | 1/18/1995 | 10/1/1994 | 5/6/1992 | 4/10/2003 |

| Treatment date | 5/28/2002 | 8/13/2001 | 1/20/1994 | 5/2/2002 | 3/4/2003 | 10/15/2003 | 8/12/2003 | 6/1/2001 | 12/2/1997 | 4/20/1994 | 5/5/2003 |

| Follow-up, mo | 18+ | 28+ | 118+ | 17+ | 9+ | 5+ | 4+ | 30+ | 72+ | 115+ | 7+ |

| Current status | Alive | Alive | Alive | Alive | Alive | Alive | Alive | Alive | Alive | Dead | Alive |

| Prior treatment | None | HU, IFN | None | None | HU | Pred | HU, Pred | Pred, HU, IFN | Pred, HU, CsA, IFN | None | None |

| Imatinib mesylate induction/maintenance, mg/d or mg/BIW | 100/100 | 100/100 | NA | 100/100 | 100/100 | 100/100 | 100/100 | 100/100 | NA | NA | 100/100 |

| Other induction treatment | NA | NA | IFN 9MU TIW none | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2-CdA (0.09 mg/kg/d × 7d/cycle) | IFN 5MU TIW + Pred 60mg/kg/d IFN 2MU TIW | NA |

| Treatment response | CR | CR | CR | CR | CR | CR | CR | CR | PR | CR | CR |

| Therapy status | |||||||||||

| Hgb level, g/dL | |||||||||||

| Before | 12.1 | 9.2 | 14.6 | 7.7 | 13.9 | 14 | 14.4 | 11.0 | 11.1 | 12.7 | 11.6 |

| After | 15.1 | 15.3 | 15.7 | 16.5 | 15.3 | 15.2 | 14.7 | 13.9 | 11.6 | 13.8 | 14.2 |

| WBC count, × 109/L | |||||||||||

| Before | 14.5 | 69.8 | 12.2 | 14.3 | 15.2 | 24.1 | 7.2 | 18.3 | 94.1 | 38.8 | 18.7 |

| After | 4.9 | 6.1 | 7.0 | 6.9 | 6.6 | 6.3 | 6.6 | 7.3 | 9.4 | 4.0 | 6.6 |

| AEC count, × 109/L | |||||||||||

| Before | 10.7 | 16.1 | 4.6 | 2.2 | 10.2 | 12.2 | 2.1 | 15.0 | 81.9 | 14.0 | 10.1 |

| After | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 4.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Platelet count, × 109/L | |||||||||||

| Before | 118 | 31 | 178 | 53 | 213 | 206 | 143 | 135 | 112 | 81 | 151 |

| After | 169 | 179 | 134 | 117 | 227 | 271 | 171 | 245 | 141 | 132 | 232 |

| CHIC2 deletion, % abnormal nuclei | |||||||||||

| Before | 61.0 | 58.0 | 47.0 | 87.5 | 76.0 | 45 | 48.0 | 42.0 | 64.0 | 80.0 | 74.0 |

| After | 0.0 | 1.5 | ND | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

All patients are male.

HU indicates hydroxyurea; IFN, interferon; Pred, prednisone; CsA, cyclosporine A; BIW, twice a week; d, day; NA, not applicable; MU, million units; TIW, thrice a week; 2-CdA, 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; Hgb, hemoglobin; WBC, white blood cell count; AEC, absolute eosinophil count; and ND, not done.

In contrast to the treatment experience in CHIC2-deleted patients, only 4 of the 10 imatinib-treated patients with HES that is not associated with CHIC2 deletion responded and then with only a partial remission. Furthermore, these 4 HES patients required a higher dose of imatinib mesylate (400 mg/d) and a longer time (always > 2 weeks and sometimes 4-6 weeks) to attain a PR. None of the 5 patients with SMCD-eos (2 with and 3 without c-kit D816V mutation) or the 2 patients with clonal eosinophilia that lacked the CHIC2 deletion responded to imatinib therapy.

Of the 10 HES patients that did not carry the CHIC2 deletion and were treated with imatinib, 7 had a serum tryptase level measured and 2 had slightly elevated values (16.5 and 20 ng/mL; normal serum tryptase level is < 11.5 ng/mL). As stated before, these 2 patients did not have abnormal mast cell infiltration of the bone marrow by tryptase staining. Both patients with elevated tryptase levels were treated and only one responded with a PR. Of the same 10 patients, 5 of the 8 patients who had a baseline serum interleukin-5 (IL-5) level measured had elevated values. All 4 HES patients who achieved a PR had their IL-5 levels measured and it was elevated in 3. In addition, 4 of the 10 imatinib-treated HES patients had gene rearrangement studies for a T-cell clone performed and one had a positive test. The latter patient did not respond, whereas 2 of the 3 with negative test results responded with a PR.

Discussion

We have examined the prevalence of the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion as detected by deletion or translocation of the CHIC2 locus at 4q12 by FISH in a cohort of 89 unselected patients with moderate to severe eosinophilia. We found a low prevalence of the particular mutation (12% in the entire cohort and 14% in patients with primary eosinophilia) that appears to be closely associated with a unique subset of patients with systemic mastocytosis that display prominent peripheral blood eosinophilia and loose rather than tight bone marrow mast cell aggregates. It is to be recalled that blood eosinophilia accompanies SMCD in approximately 20% of all patients.14 In the current study, 53% of such patients carried the CHIC2 deletion/translocation. The uniform absence of the c-kit D816V mutation in CHIC2-deleted SMCD-eos suggests that the 2 mutations are mutually exclusive disease-causing events that may have a similar but not identical clinical phenotype. However, c-kit D816V mutation was detected in only 3 of the 9 SMCD-eos cases without CHIC2 deletion, an observation that raises the existence of yet another unidentified molecular lesion in the specific patient subset. Given the relative overrepresentation of CHIC2 deletion or translocation in SMCD-eos patients, we studied a cohort of 20 SMCD patients who did not have associated eosinophilia and did not detect deletion or translocation of the CHIC2 locus in any of these patients (data not shown).

In contrast to the relatively high prevalence of CHIC2 deletion in SMCD-eos, the specific mutation was not detected in any of the 57 cases from the current series that carried the clinical diagnosis of HES. However, it is important to point out the fact that 7 of the 10 CHIC2-deleted cases with SMCD-eos were initially diagnosed as having HES and only after careful review of the bone marrow histology, tryptase immunohistochemistry, mast cell immunophenotyping, and serum tryptase levels was the diagnosis of SMCD-eos established. As a matter of fact, we had stored samples, which allowed FISH testing for CHIC2 deletion, from 1 of the original 4 patients who were initially diagnosed with HES and were reported to be responsive to imatinib.2 This patient (50-year-old male; Table 5) has since been reclassified as FIP1L1-PDGFRA+ SMCD-eos after rereview of the bone marrow biopsy with tryptase staining. In comparing the cohort of patients (after reclassification) having true HES with SMCD-eos, it becomes evident that the clinical presentation does not reliably distinguish one from another due to significant overlap (both entities might be associated with eosinophilic cardiac and neurologic disease), even though at least half of the CHIC2-deleted SMCD-eos patients displayed characteristic features of systemic mastocytosis, including urticaria pigmentosa, pruritus, diarrhea, fat malabsorption, severe weight loss, bone pain, headache, and constitutional symptoms (Table 2). This diagnostic dilemma is compounded by the atypical pattern of mast cell infiltration for most SMCD-eos cases that carry the CHIC2 deletion or translocation (Figure 4). The looser, ill-defined aggregates of mast cells for some patients in this subgroup are easily missed on routine H&E-stained sections, and careful review of tryptase-immunostained sections, which we recommend be done for all cases of nonreactive eosinophilia, may be crucial to identifying these infiltrates. Additional tests including bone marrow mast cell immunophenotyping and measurement of serum tryptase levels may assist in distinguishing true HES from SMCD-eos. Our data suggest that a significant proportion, perhaps the majority, of patients with HES recently reported to have achieved dramatic responses to imatinib therapy may, in fact, be proven to have SMCD-eos if [such] adjunctive testing were performed.

While we have classified patients with the CHIC2 deletion as SMCD-eos, based primarily on their distinctive clinicopathologic features, but also based on the fact that 3 of the 10 patients were diagnosed as such even prior to the discovery of the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion,4 we remain sensitive to the issue that this subgroup of patients may represent a disease that is distinct from both HES and SMCD. We stress that their classification as SMCD-eos be considered tentative until such time that larger numbers of patients are studied and the natural history of this entity is better defined.

The validity of our FISH data are borne out by the imatinib response data. Only those patients identified as carrying the CHIC2 deletion had a CR with imatinib therapy (Tables 1 and 5). A minority of HES patients achieved a PR and none a CR in contrast to the preliminary reports from earlier studies that suggested a high CR rate for patients with HES who responded to imatinib therapy.3,6 Furthermore, the partial responders required a higher dose of imatinib (400 mg/d) for longer periods of time compared with the lower dose (100 mg/d), which rapidly induces a CR in the vast majority of complete responders. This finding argues that our FISH strategy is not significantly underestimating the presence of the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion in this cohort of patients. In a limited subgroup of HES patients without the CHIC2 deletion, neither the serum tryptase level nor the serum IL-5 level appear to be correlated with treatment response.

We were unable to discern any clinical or histopathologic differences between the 9 SMCD-eos patients who had CHIC2 deletion and the single SMCD-eos patient who had translocation of the CHIC2 locus to 7q11.2. Additional patients carrying translocation of the CHIC2 locus will need to be studied to examine the significance of CHIC2 loss versus translocation, if any.

Clinical observations regarding the therapeutic activity of imatinib in eosinophilic disorders as well as systemic mastocytosis have led to the discovery of FIP1L1-PDGFRA as an eosinophilia-associated imatinib target. The current article provides a general estimate of the prevalence of this interesting mutation in primary eosinophilia and also suggests a close association with a subset that is characterized by bone marrow infiltration with morphologically as well as immunophenotypically aberrant mast cells. Regardless of what one chooses to call FIP1L1-PDGFRA+ eosinophilic disorder, its detection warrants a therapeutic trial with imatinib. Additional studies are needed to determine the optimal drug dose that would assure a durable molecular remission. Similarly, more studies are needed to clarify the role of imatinib therapy in FIP1L1-PDFGRA– HES. For now, it is reasonable to screen for the presence of FIP1L1-PDGFRA in patients with SMCD-eos as well as in those with the clinical phenotype of HES. In contrast, we do not recommend screening for CHIC2 deletion in SMCD that is not associated with eosinophilia.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, July 29, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0787.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears in the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

Ching-Liang Ho is a visiting scientist from the Division of Hematology, Tri-Service General Hospital, National Defense Medical Center, Taipei, Taiwan.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal