The interleukin-6 receptor (IL-6R)/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) pathway contributes to the pathogenesis of multiple myeloma (MM) and protects MM cells from apoptosis. However, MM cells survive the IL-6R blockade if they are cocultured with bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs), suggesting that the BM microenvironment stimulates IL-6–independent pathways that exert a pro-survival effect. The goal of this study was to investigate the underlying mechanism. Detailed pathway analysis revealed that BMSCs stimulate STAT3 via the IL-6R, and mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases via IL-6R–independent mechanisms. Abolition of MEK1,2 activity with PD98059, or ERK1,2 small interfering RNA knockdown, was insufficient to induce apoptosis. However, the combined disruption of the IL-6R/STAT3 and MEK1,2/ERK1,2 pathways led to strong induction of apoptosis even in the presence of BMSCs. This effect was observed with MM cell lines and with primary MM cells, suggesting that the BMSC-induced activation of MEK1,2/ERK1,2 renders MM cells IL-6R/STAT3 independent. Therefore, in the presence of cells from the BM micro-environment, combined targeting of different (and independently activated) pathways is required to efficiently induce apoptosis of MM cells. This might have direct implications for the development of future therapeutic strategies for MM.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant hematologic disorder that accounts for approximately 1% of all cancer-related deaths in Western countries.1 Even though advanced chemotherapeutic regimens such as high-dose chemotherapy and autologous blood stem cell transplantation have increased the median time of survival to 4 to 5 years, MM remains incurable.2 The disease is characterized by an accumulation of plasma cells in the bone marrow (BM) leading to impaired hematopoiesis and to osteolytic bone destruction. The BM microenvironment is thought to provide essential support for the propagation and expansion of the malignant clone.3 Specifically, it has been shown that survival, growth, and drug sensitivity of MM cells are affected by their interaction with BM stromal cells (BMSCs), which constitute a major cellular compartment of the BM.4,5 The interplay between MM cells and BMSCs sustains cell adhesion–mediated drug resistance and induces increased levels of growth-promoting chemokines and cytokines.6,7 Of the latter, interleukin-6 (IL-6), which is known to be required for the terminal differentiation of B cells, is presumed to play a major role in the pathogenesis and malignant growth of multiple myeloma.8,9

Stimulation of cells by IL-6 requires signaling through the IL-6 receptor (IL-6R), which consists of 2 subunits: IL-6Rα and IL-6Rβ, which is the signal transducing chain.10 Binding of IL-6 to IL-6Rα induces recruitment of IL-6Rβ subunits and initiates at least 2 intracellular signaling pathways: the Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (JAK/STAT3), and the Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway.11 IL-6–mediated induction of the Ras/MAPK pathway has been reported to correlate with the proliferation characteristics of IL-6–dependent MM cells.12-14 However, data on the precise role of the MAP kinases ERK1,2 for the propagation of MM cells remains sketchy and consequently it is still unclear if the MEK1,2/ERK1,2 module represents a reasonable target for therapeutic intervention. STAT3, on the other hand, was found to be constitutively phosphorylated in a high proportion of primary myeloma samples,15,16 and it has been demonstrated that inhibition of the IL-6R/STAT3 pathway with IL-6R antagonists,17 JAK-inhibitors,18 or dominant-negative STAT3 expression constructs15 induces apoptosis of human myeloma cell lines in vitro. These experiments highlighted the potential importance of this pathway for antiapoptotic signaling in myeloma cells and identified it as an interesting target for the development of therapeutic strategies against MM. The upshot of both these pathway analyses is to implicate IL-6R/STAT3 signaling primarily with survival, and the IL-6R/MAPK pathway with proliferation of MM cells. However, most data concerning the role of these IL-6–triggered pathways were gleaned from experiments with cell lines, and without consideration of the BM microenvironment. Therefore, the function and biologic significance of these pathways, and their potential for therapeutic interference, are still unclear. Recently, we have shown that inhibition of the IL-6R/STAT3 pathway in the IL-6–dependent MM cell line INA-6 is correlated with induction of apoptosis in the absence of BMSCs, whereas no or only minor effects on either growth or survival were observed in the presence of BMSCs.19 These observations indicate that IL-6R/STAT3 signaling is dispensable within the context of the BM microenvironment, which might stimulate IL-6–independent pathways that protect MM cells from apoptosis. We found that activation of ERK1,2 in INA-6 cells was only slightly enhanced by IL-6, but strongly induced by BMSCs. Furthermore, treatment with the farnesyl transferase inhibitor FPT III, which disrupts Ras signaling, provoked a strong apoptotic response even under coculture conditions.19 We therefore speculated that BMSC-induced ERK activity might compensate for the lack of IL-6R/STAT3–mediated antiapoptotic signals. In this study, we analyzed whether selective blockade of the MEK1,2/ERK1,2 module, rather than disruption of the IL-6R/STAT3 pathway, constitutes an effective means to induce apoptosis of MM cells if these are cultured in the presence of BMSCs.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The human IL-6–dependent MM cell lines INA-620 and ANBL-621 were maintained in RPMI 1640, supplemented with either 20% or 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; both from Biochrom, Berlin, Germany), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin (both from PAN Biotech, Aidenbach, Germany), 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM Na-pyruvate (both from Gibco, Karlsruhe, Germany), and 2 ng/mL recombinant IL-6. For cell culture of primary cells, see Chatterjee et al.19 All cells were grown at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Electroporation of INA-6 cells

INA-6 cells at densities of 4 × 105/mL were collected at 200g, and, following complete removal of the supernatant, resuspended at 1 × 107/mL in fresh RPMI medium without additives. Electroporation employed a Gene Pulser (BIO-RAD, München, Germany) and cuvettes (d = 0.4 cm; Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) at settings of 960 μF and 280 V, respectively. The concentration of plasmids was 10 μg/mL for pEGFP, 20 μg/mL for pCD4 Δ, and 10 μg/mL for pSUPER constructs. A quantity of 500 μL cell suspension was used per electroporation. Electroporated cells were mixed with an equal volume of medium without additives, kept at 37°C until all samples were addressed, and then transferred to prewarmed full medium with IL-6 to recover overnight.

Purification of electroporated INA-6 cells

Overnight cultures of transfected cells were collected at 200g, washed with cold 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 5 mM EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), spun again, resuspended in 320 μL cold separation buffer (1× PBS, 0.5% FCS, 2.5 mM EDTA), and mixed with 80 μL MACSelect 4 MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Following incubation at 4°C for 15 minutes, 1.5 mL cold separation buffer was added and the suspension applied to a Large Cell Column (Miltenyi Biotec). The column was washed with 2 mL cold separation buffer and retained cells were collected with 3 mL full medium. Because this procedure also retains large numbers of dead cells, an additional purification step was included, for which the cells were collected at 200g, resuspended in a 3.3:1 mixture of full medium/OptiPrep (Axis-Shield, Oslo, Norway), and subjected to density gradient centrifugation at 1400g for 5 minutes. The live cell fraction was reclaimed, washed, and resuspended in full medium.

Construction of siRNA expression vectors

pSUPER-derived expression vectors for small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) against ERK1, ERK2, and STAT3, were designed according to guidelines in Brummelkamp et al.22 Efficacy of the constructs was tested through electroporation into INA-6 cells and Western blot analysis of the respective target in purified cells after 1 to 4 days. The sequences for the sense oligonucleotides for the most effective knockdown constructs are (sequence derived from the actual genes in bold): 5′-dGATCCCCGCCATGAGAGATGTCTACATTCAAGAGATGTAGACATCTCTCATGGCTTTTTGGAAA-3′ (based on positions 340 to 358 of human ERK1), 5′-dGATCCCCGAGGATTGAAGTAGAACAGTTCAAGAGACTGTTCTACTTCAATCCTCTTTTTGGAAA-3′ (based on positions 900 to 918 of human ERK2) and 5′-dGATCCCCCTTCAGACCCGTCAACAAATTCAAGAGATTTGTTGACGGGTCTGAAGTTTTTGGAAA-3′ (based on positions 823 to 841 of human STAT3).

Construction of an expression plasmid for siRNA-resistant STAT3 (pS3R)

A 672-bp XbaI/BamHI fragment from a human STAT3 clone (a kind gift from Dr de Groot, SRON, Utrecht, The Netherlands) that contained the target sequence for the STAT3 siRNA, was subcloned into pBluescript, and 5 silent mutations were introduced within the target sequence. The sequence of the sense oligonucleotide that was used in combination with the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) is 5′-dAATCTCAACTGCAAACGCGGCAGCAAATTAAGA-3′ (based on positions 815 to 847 of human STAT3, with mutated positions underlined). The insert was verified by sequencing and cloned back into the XbaI and BamHI sites of the human STAT3 clone. In order to introduce an HA (hemagglutinin) tag, the first 470 bases of this clone were exchanged for the equivalent but HA-tagged murine sequence (a kind gift from Prof Hamaguchi, Nagoya University, Japan) via the common XbaI site, and the chimeric STAT3 gene was cloned into the expression vector pCAGGS. This plasmid was used at a concentration of 10 μg/mL in electroporations.

Preparation of primary myeloma cells and BMSCs

Please refer to Chatterjee et al19 for general details on the preparation and maintenance of these cells. BMSCs were derived from the mononuclear cell fraction of bone marrow aspirates after Ficoll density gradient centrifugation. BMSCs were obtained from 2 patients with multiple myeloma and one patient with morbus Hodgkin, and maintained in culture for up to 6 months. All samples were taken from routine diagnostic specimens after informed consent of the patients and permission by the local ethics committee.

Coculture of myeloma cells and BMSCs, and application of drugs

Between 1 × 104 and 2 × 104 myeloma cells per well were seeded in 96-well plates and kept overnight in 200 μL medium. If the experiments were to include primary BMSCs, those were taken from cultures with passage numbers no higher than 5, seeded in full Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) at 1 × 103 per well, and given time to attach for at least one day prior to application of myeloma cells. Cultures that did not contain BMSCs were supplemented with 2 ng/mL IL-6. To apply the drugs, 100 μL medium was removed, thoroughly mixed with stock solutions of the respective compound or compounds so as to yield final concentrations of 50 μM for PD98059 and 50 μg/mL for Sant7, and then added back to the respective well. Control incubations containing the solvent for PD98059 (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) were always included. After 3 days cells were assayed for apoptosis or proliferation.

Apoptosis assay

To assess the percentage of apoptotic cells, a human annexin V–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) kit (Bender MedSystems, Eching, Germany) was used. Cells were washed in PBS, collected at 200g, and the supernatant aspirated. Samples were incubated for 10 minutes in 100 μL binding buffer (10 mM HEPES [N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid]/NaOH, pH 7.4, 140 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2) containing 2.5 μL annexin V–FITC mix and 1 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI), subsequently diluted with 300 μL binding buffer and analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur/CELLQuest; Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany).

Proliferation assay

Proliferation assays were performed in 96-well plates, with each combination of drugs and cells measured in triplicate. Two days after 1 × 104 cells had been seeded, 0.25 μCi (9,25 kBq) [3H]-thymidine (Perkin Elmer, Rodgau-Jüdesheim, Germany) was added per well and cells were harvested, and the incorporated radioactivity counted, after overnight culture.

Western blot analysis

Myeloma cells cocultured with BMSCs were washed off to avoid contamination with stromal cells. Otherwise, all procedures followed those detailed in Chatterjee et al,19 except that an anti–α-tubulin antibody was employed to assess equal loading.

Reagents

The following antibodies were used: anti-ERK1/2 (no. 442675; Calbiochem, Schwalbach, Germany), anti–phospho-ERK1/2 (no. 9101; Cell Signaling Technologies [CST], Frankfurt/Main, Germany), rat anti–α-tubulin (Serotec, Düsseldorf, Germany), anti-STAT3 (no. 9132; CST), anti–phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705; no. 9131; CST). Biotinylated secondary antibodies were from Promega (Mannheim, Germany). The expression plasmid for enhanced green fluorescent protein (pEGFP-N3) was bought from Clontech (Heidelberg, Germany), and the expression plasmid for human truncated CD4 was constructed by subcloning the CD4 Δ cDNA from pMACS 4.1 (Miltenyi Biotec) into the EcoRI/HindIII sites of pcDNA3.1+ (Invitrogen). The pSUPER vector was kindly provided by Dr Agami (The Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). PD98059 was purchased from Calbiochem (no. 513000). Human ΔN40 IL-6 and Sant7,23,24 both modified to contain a myc/His-tag at the C-terminus, were produced in our laboratory in recombinant E coli (BL-21), and purified via binding to Ni-NTA Agarose (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's guidelines. Aliquots of the purified proteins in final dialysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, 10% glycerol, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, pH 8.0) were stored at –80°C.

Statistical analysis

To assess the differences between specifically manipulated cells and the respective controls, statistical analyses using a 2-tailed unpaired Student t test were performed. P values of less than .05 were considered significant; those lower than .001 were regarded as very significant.

Results

Selective inhibition of the MEK1,2/ERK1,2 module in INA-6 cells

In this study, we wanted to investigate the significance of signaling through the MEK1,2/ERK1,2 module for the survival of myeloma cells. Starting with the IL-6–dependent cell line INA-6, we tested if this pathway could be specifically interrupted through transient transfection with expression vectors for siRNAs. Using an electroporation protocol and an expression plasmid for EGFP, we found that 20 hours after electroporation, up to 30% of INA-6 cells strongly expressed EGFP (Figure 1A). To isolate the live and transfected cells, an expression plasmid for truncated CD4 (pCD4 Δ) was electroporated and the cells purified through paramagnetic bead separation, followed by density gradient centrifugation. Up to 90% of the final cell fraction was viable and strongly transfected, with negligible numbers of untransfected cells (Figure 1A). These cells remained perfectly viable over the course of several days.

Transfection of INA-6 myeloma cells and selective targeting of ERK1, ERK2, and STAT3 with siRNAs. (A) FACS analysis of INA-6 cells after electroporation with a mixture of expression vectors for EGFP, truncated CD4 (CD4 Δ), and pSUPER. From left to right: 20 hours after transfection but before purification, 24 hours after transfection and after purification of live transfected cells, and 4 days after transfection with maintenance in culture. Of note are high numbers of initially transfected myeloma cells, the selective enrichment of the most strongly transfected live cells, and the generally good viability of these cells in culture. Numbers in the inset represent the percentage of events within the respective quadrant. (B) Western blot analysis of ERK1,2 and phospho-ERK1,2 in purified INA-6 cells 72 hours after electroporation with expression plasmids for siRNAs against ERK1 or ERK2 (pSU-ERK1, pSU-ERK2), or a combination of both (pSU-ERK1 + 2). Shown is the strong and selective knockdown of the targeted protein(s), and the near absence of the respective activated form(s) even after stimulation with PMA (25 μg/mL) for 30 minutes. Basal phosphorylation of ERK became undetectable after expression of the siRNAs. (C) Western blot analysis of STAT3 in INA-6 cells electroporated with an expression plasmid for an siRNA against STAT3 (lane 2), and of cells additionally transfected with an expression plasmid (pS3R) for HA-tagged STAT3 protein derived from a sequence not recognized by the siRNA (lane 4). Shown is the near absence of STAT3 in the siRNA-transfected cells, and replenishment of the STAT3 pool through concomitant expression of the tagged, genetically modified version. Antibody staining of α-tubulin served as loading control.

Transfection of INA-6 myeloma cells and selective targeting of ERK1, ERK2, and STAT3 with siRNAs. (A) FACS analysis of INA-6 cells after electroporation with a mixture of expression vectors for EGFP, truncated CD4 (CD4 Δ), and pSUPER. From left to right: 20 hours after transfection but before purification, 24 hours after transfection and after purification of live transfected cells, and 4 days after transfection with maintenance in culture. Of note are high numbers of initially transfected myeloma cells, the selective enrichment of the most strongly transfected live cells, and the generally good viability of these cells in culture. Numbers in the inset represent the percentage of events within the respective quadrant. (B) Western blot analysis of ERK1,2 and phospho-ERK1,2 in purified INA-6 cells 72 hours after electroporation with expression plasmids for siRNAs against ERK1 or ERK2 (pSU-ERK1, pSU-ERK2), or a combination of both (pSU-ERK1 + 2). Shown is the strong and selective knockdown of the targeted protein(s), and the near absence of the respective activated form(s) even after stimulation with PMA (25 μg/mL) for 30 minutes. Basal phosphorylation of ERK became undetectable after expression of the siRNAs. (C) Western blot analysis of STAT3 in INA-6 cells electroporated with an expression plasmid for an siRNA against STAT3 (lane 2), and of cells additionally transfected with an expression plasmid (pS3R) for HA-tagged STAT3 protein derived from a sequence not recognized by the siRNA (lane 4). Shown is the near absence of STAT3 in the siRNA-transfected cells, and replenishment of the STAT3 pool through concomitant expression of the tagged, genetically modified version. Antibody staining of α-tubulin served as loading control.

In order to knockdown ERK1 and ERK2, we designed a number of siRNA expression vectors based on pSUPER22 and tested these through transient transfection into INA-6 cells. One construct against each target was highly effective at eliminating the respective protein within 3 days (Figure 1B). Stimulation with PMA (phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate) [25 μg/mL], a strong nonspecific inducer of ERK1,2 phosphorylation, confirmed that very little activatable protein remained in the respective siRNA-treated samples (Figure 1B). Cotransfection of both siRNA vectors resulted in a near-complete knockdown of both ERK proteins (Figure 1B). Basal level activation of ERK1 and ERK2, which in INA-6 cells may be a consequence of an activating N-ras mutation,20 was no longer detectable in the double transfectants (Figure 1B, Figure 2A).

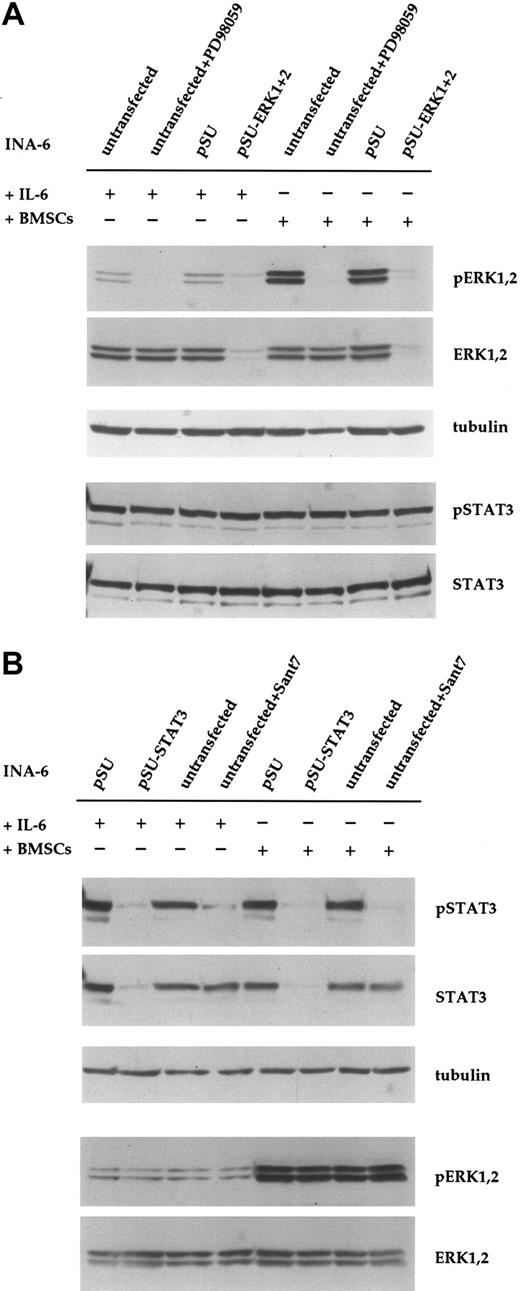

Down-regulation of ERK1,2 phosphorylation with siRNA or PD98059 does not affect phosphorylation of STAT3 in INA-6 cells. (A) INA-6 cells kept in medium with IL-6 or in coculture with BMSCs, and with or without blockade of the MEK1,2/ERK1,2 module with the pharmacologic inhibitor PD98059 (50 μM) or with siRNAs for ERK1 and ERK2. Note the absence of basal levels of phosphorylated ERK1,2 protein in samples transfected with siRNA expression constructs or incubated with PD98059, and the lack of any effect of these treatments on the phosphorylation of STAT3 at Tyr705. Also note the much stronger phosphorylation of ERK1,2 in cells cocultured with BMSCs, and its absence in samples transfected with pSU-ERK1 + 2 siRNA expression vectors or incubated with PD98059. Equal loading and equal presence of STAT3 were assessed through immunostaining for α-tubulin and STAT3, respectively. (B) INA-6 cells kept in medium with IL-6 or in coculture with BMSCs, and with or without blockade of IL-6R/STAT3 signaling, either with the IL-6R superantagonist Sant7 (50 μg/mL) or an siRNA specific for STAT3. Treatment with Sant7, or expression of the siRNA, led to a strong decrease in the amount of phosphorylated STAT3 in medium with IL-6, but also in the presence of BMSCs. The siRNA caused a near-complete loss of STAT3 protein, whereas Sant7 treatment only affected phosphorylation. These treatments had no effect on the phosphorylation status or expression level of ERK1,2. α-tubulin staining served as loading control.

Down-regulation of ERK1,2 phosphorylation with siRNA or PD98059 does not affect phosphorylation of STAT3 in INA-6 cells. (A) INA-6 cells kept in medium with IL-6 or in coculture with BMSCs, and with or without blockade of the MEK1,2/ERK1,2 module with the pharmacologic inhibitor PD98059 (50 μM) or with siRNAs for ERK1 and ERK2. Note the absence of basal levels of phosphorylated ERK1,2 protein in samples transfected with siRNA expression constructs or incubated with PD98059, and the lack of any effect of these treatments on the phosphorylation of STAT3 at Tyr705. Also note the much stronger phosphorylation of ERK1,2 in cells cocultured with BMSCs, and its absence in samples transfected with pSU-ERK1 + 2 siRNA expression vectors or incubated with PD98059. Equal loading and equal presence of STAT3 were assessed through immunostaining for α-tubulin and STAT3, respectively. (B) INA-6 cells kept in medium with IL-6 or in coculture with BMSCs, and with or without blockade of IL-6R/STAT3 signaling, either with the IL-6R superantagonist Sant7 (50 μg/mL) or an siRNA specific for STAT3. Treatment with Sant7, or expression of the siRNA, led to a strong decrease in the amount of phosphorylated STAT3 in medium with IL-6, but also in the presence of BMSCs. The siRNA caused a near-complete loss of STAT3 protein, whereas Sant7 treatment only affected phosphorylation. These treatments had no effect on the phosphorylation status or expression level of ERK1,2. α-tubulin staining served as loading control.

PD98059 is a pharmacologic inhibitor of the kinases MEK1,2, which are possibly the only activators of ERK1,2. To compare the effect of siRNA-mediated knockdown of ERK1,2 with inhibition at the level of MEK1,2, we incubated INA-6 cells with PD98059 (50 μM) for 12 hours. This treatment voided the basal phosphorylation of both ERK1 and ERK2 (Figure 2A). As expected, and in contrast to the effect of siRNAs, the protein level of ERK1 and ERK2 protein was not altered by treatment with PD98059. We have previously observed that phosphorylation of ERK1,2 in INA-6 cells is strongly enhanced in the presence of BMSCs.19 To assess whether this strong ERK1,2 activity was efficiently blocked with siRNAs or by PD98059, we tested both approaches in INA-6 cells cocultured with primary BMSCs. Again, phosphorylation of ERK1 and ERK2 was strongly reduced in both settings (Figure 2A). Notably, neither ERK1,2 knockdown nor treatment with the MEK inhibitor affected the phosphorylation of STAT3 at Tyr705 (Figure 2A) or at Ser727 (data not shown). Inhibition of the IL-6R/STAT3 pathway with the specific IL-6R antagonist Sant7 (which is derived from IL-6 through 7 amino acid changes that endow the polypeptide with a 70-fold higher binding activity at the IL-6Rα chain and abolish any agonist activity23,24 ) did not affect the phosphorylation of ERK1,2, either in the absence or in the presence of BMSCs (Chatterjee et al19 and Figure 2B). This suggests that in INA-6 MM cells, the MAP kinases ERK1,2 are activated mainly by IL-6–independent mechanisms.

Knockdown of STAT3 protein in INA-6 cells

To specifically abrogate signaling through the IL-6R/STAT3 pathway at the level of STAT3, and thus downstream of potential pathway ramifications at the IL-6R, we again used a pSUPER-derived siRNA expression plasmid. The STAT3 siRNA caused strong down-regulation of STAT3 protein within 2 days (Figure 1C), and the affected cells were efficiently driven into apoptosis between 2 and 4 days after transfection (Figure 3B). This result excellently mimicked the effects of IL-6 removal or IL-6R blockade. The specificity of this effect was shown through concomitant transfection of the siRNA expression plasmid and an expression plasmid for a tagged STAT3 protein (pS3R), derived from a coding sequence that was rendered unrecognizable for the STAT3 siRNA (Figure 1C). This construct was sufficient to prevent the near-complete demise of siRNA-transfected cells and rescued them to half the level of control cells or better, as assessed by apoptosis and proliferation assays (Figure 3E, Figure 4C).

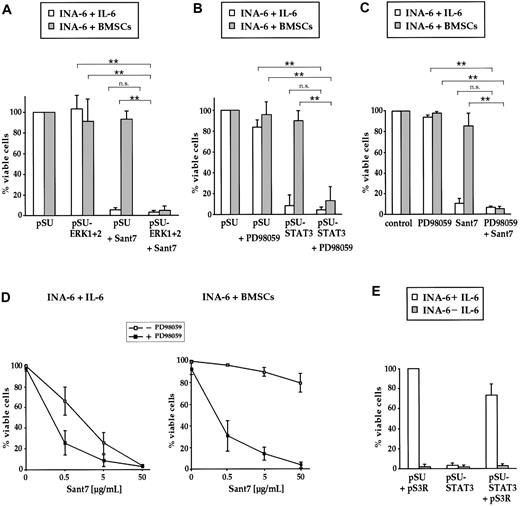

Combined targeting of the IL-6R/STAT3 pathway and the MEK1,2/ERK1,2 module induces apoptosis of INA-6 cells even in the presence of BMSCs. (A) INA-6 cells transfected with expression plasmids for siRNAs against ERK1 and ERK2 (pSU-ERK1 + 2), or control plasmid (pSU), were cultured in medium with IL-6 (□) or in the presence of BMSCs (▦), and treated with or without 50 μg/mL Sant7. Apoptosis was assayed after 3 days and survival of the respective pSU-transfected samples was set as 100%. Sant7 induced strong cell death in medium and knockdown of ERK1,2 had no effect. In the presence of BMSCs, myeloma cells were protected from the apoptotic effect of Sant7, and blockade of both the IL-6R/STAT3 and the MAPK pathways was required for apoptosis. (B) INA-6 cells transfected with an expression plasmid for an siRNA against STAT3 (pSU-STAT3) or control plasmid (pSU), cultured as described in panel A and treated with or without 50 μM PD98059. In the presence of BMSCs, the combination of both drugs (ie, blockade of the IL-6R/STAT3 and the MAPK pathways) was required for apoptosis. (C) INA-6 cells cultured as described in panel A and treated with 50 μM PD98059 and/or 50 μg/mL Sant7. The effects of both pharmacologic inhibitors mimicked those of the siRNAs that abrogate the respective pathway. (D) INA-6 cells cultured in medium with IL-6 (top) or in the presence of BMSCs (bottom) without (□) or with (▪) 50 μM PD98059, and with increasing concentrations of Sant7. Increasing concentrations of Sant7 alone were sufficient to kill the cells in medium, but the combination of both pathway blockers was required to achieve the same result in the presence of BMSCs. (E) Expression of STAT3 protein that is derived from a sequence no longer recognizable by the siRNA (plasmid pS3R) largely blocked the detrimental effects of STAT3 siRNA expression (□). Cell death induced through IL-6 depletion was not affected ( ). All data shown are derived from at least 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis (A-C) revealed very significant (**) or no (n.s. = not significant) differences as indicated. Error bars denote the range of values derived from at least 3 independent experiments.

). All data shown are derived from at least 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis (A-C) revealed very significant (**) or no (n.s. = not significant) differences as indicated. Error bars denote the range of values derived from at least 3 independent experiments.

Combined targeting of the IL-6R/STAT3 pathway and the MEK1,2/ERK1,2 module induces apoptosis of INA-6 cells even in the presence of BMSCs. (A) INA-6 cells transfected with expression plasmids for siRNAs against ERK1 and ERK2 (pSU-ERK1 + 2), or control plasmid (pSU), were cultured in medium with IL-6 (□) or in the presence of BMSCs (▦), and treated with or without 50 μg/mL Sant7. Apoptosis was assayed after 3 days and survival of the respective pSU-transfected samples was set as 100%. Sant7 induced strong cell death in medium and knockdown of ERK1,2 had no effect. In the presence of BMSCs, myeloma cells were protected from the apoptotic effect of Sant7, and blockade of both the IL-6R/STAT3 and the MAPK pathways was required for apoptosis. (B) INA-6 cells transfected with an expression plasmid for an siRNA against STAT3 (pSU-STAT3) or control plasmid (pSU), cultured as described in panel A and treated with or without 50 μM PD98059. In the presence of BMSCs, the combination of both drugs (ie, blockade of the IL-6R/STAT3 and the MAPK pathways) was required for apoptosis. (C) INA-6 cells cultured as described in panel A and treated with 50 μM PD98059 and/or 50 μg/mL Sant7. The effects of both pharmacologic inhibitors mimicked those of the siRNAs that abrogate the respective pathway. (D) INA-6 cells cultured in medium with IL-6 (top) or in the presence of BMSCs (bottom) without (□) or with (▪) 50 μM PD98059, and with increasing concentrations of Sant7. Increasing concentrations of Sant7 alone were sufficient to kill the cells in medium, but the combination of both pathway blockers was required to achieve the same result in the presence of BMSCs. (E) Expression of STAT3 protein that is derived from a sequence no longer recognizable by the siRNA (plasmid pS3R) largely blocked the detrimental effects of STAT3 siRNA expression (□). Cell death induced through IL-6 depletion was not affected ( ). All data shown are derived from at least 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis (A-C) revealed very significant (**) or no (n.s. = not significant) differences as indicated. Error bars denote the range of values derived from at least 3 independent experiments.

). All data shown are derived from at least 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis (A-C) revealed very significant (**) or no (n.s. = not significant) differences as indicated. Error bars denote the range of values derived from at least 3 independent experiments.

Effects of IL-6R/STAT3 and MAPK pathway blockade on the proliferation of INA-6 cells. (A) INA-6 cells transfected with expression plasmids for siRNAs against ERK1 and ERK2 (pSU-ERK1 + 2) or with control plasmid (pSU), and untransfected cells treated with PD98059, were cultured in medium with IL-6 (left) or in the presence of BMSCs (right) and their proliferation assayed after 3 days. Proliferation (ie, incorporation of [3H]-thymidine) was very similar for cells cultured in medium or on BMSCs with a less than 20% difference in total counts. Within each experimental set the proliferation of unmanipulated cells was arbitrarily set as 100%. Blockade of MEK1,2/ERK1,2 signaling slightly reduced proliferation in both settings. (B) INA-6 cells transfected with an expression plasmid for an siRNA against STAT3 (pSU-STAT3) or with control plasmid (pSU), and untransfected cells treated with Sant7, were cultured in medium with IL-6 (left) or in the presence of BMSCs (right). In keeping with extensive cell death, Sant7 and the siRNA abrogated all proliferation in medium, but proliferation with either treatment was only moderately reduced in the presence of BMSCs. (C) Confirmation of the specificity of STAT3 siRNA-mediated cell death. Expression of STAT3 protein that is derived from a sequence no longer recognizable by the siRNA (plasmid pS3R) largely offset the detrimental effects of STAT3 siRNA expression on the proliferation of INA-6 cells. All data shown are derived from at least 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis (A,B) revealed very significant (**), significant (*), or no (n.s. = not significant) differences as indicated. Error bars denote the range of values derived from at least 3 independent experiments.

Effects of IL-6R/STAT3 and MAPK pathway blockade on the proliferation of INA-6 cells. (A) INA-6 cells transfected with expression plasmids for siRNAs against ERK1 and ERK2 (pSU-ERK1 + 2) or with control plasmid (pSU), and untransfected cells treated with PD98059, were cultured in medium with IL-6 (left) or in the presence of BMSCs (right) and their proliferation assayed after 3 days. Proliferation (ie, incorporation of [3H]-thymidine) was very similar for cells cultured in medium or on BMSCs with a less than 20% difference in total counts. Within each experimental set the proliferation of unmanipulated cells was arbitrarily set as 100%. Blockade of MEK1,2/ERK1,2 signaling slightly reduced proliferation in both settings. (B) INA-6 cells transfected with an expression plasmid for an siRNA against STAT3 (pSU-STAT3) or with control plasmid (pSU), and untransfected cells treated with Sant7, were cultured in medium with IL-6 (left) or in the presence of BMSCs (right). In keeping with extensive cell death, Sant7 and the siRNA abrogated all proliferation in medium, but proliferation with either treatment was only moderately reduced in the presence of BMSCs. (C) Confirmation of the specificity of STAT3 siRNA-mediated cell death. Expression of STAT3 protein that is derived from a sequence no longer recognizable by the siRNA (plasmid pS3R) largely offset the detrimental effects of STAT3 siRNA expression on the proliferation of INA-6 cells. All data shown are derived from at least 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis (A,B) revealed very significant (**), significant (*), or no (n.s. = not significant) differences as indicated. Error bars denote the range of values derived from at least 3 independent experiments.

Combined inhibition of IL-6R/STAT3 and MEK1,2/ERK1,2 signaling is required to induce apoptosis of INA-6 cells in the presence of BMSCs

To assess if BMSC-mediated resistance to apoptosis is connected to the increased levels of activated ERK1,2, we investigated the effects of specific pathway blockade on the survival and proliferation of INA-6. Signaling through the MEK1,2/ERK1,2 module was blocked either by MEK1,2 inhibition with PD98059, or at the level of ERK1,2 through siRNA knockdown. IL-6R/STAT3 signaling was blocked with Sant7 at the IL-6R or further downstream through expression of STAT3 siRNA.

INA-6 cells transfected with siRNA expression constructs against ERK1 and ERK2, or untransfected cells treated with PD98059, were kept for 3 days with or without BMSCs, and assayed for apoptosis or proliferation. Interestingly, inhibition of MEK1,2 or ERK1,2 had at best very slight effects on the viability of INA-6 cells both in the absence and in the presence of BMSCs (Figure 3A-C). In accordance with reports on other myeloma cell lines,13,14,20 the proliferation of INA-6 cells in medium was decreased to about 60% of control values by treatment with PD98059, and also by expression of ERK1,2 siRNAs (Figure 4A). The antiproliferative effect of the ERK1 and ERK2 siRNAs appeared less pronounced in the presence of BMSCs, whereas treatment with PD98059 still decreased proliferation to about 70% of control.

To compare the effects of IL-6R blockade by Sant7 with siRNA knockdown of STAT3, INA-6 cells that were either untransfected or expressed the STAT3-siRNA were cultured with BMSCs or in medium with IL-6. Cells lacking functional STAT3 signaling underwent a strong apoptotic response in the absence of BMSCs and, accordingly, did not proliferate (Figure 3A-C, Figure 4B). In coculture with BMSCs, however, INA-6 cells were largely protected from apoptosis, and this was accompanied by strong incorporation of [3H]-thymidine to levels of 60% of untransfected controls (Figure 4B).

Taken together, the coculture experiments clearly demonstrated that neither the IL-6R/STAT3 pathway nor signaling through the MEK1,2/ERK1,2 module was on its own essential for the survival or proliferation of INA-6 cells in this setting. We therefore investigated the effect of concomitant disruption of both pathways and combined either Sant7 or STAT3 siRNAexpression with PD98059 or ERK1,2 siRNAexpression. Surprisingly, this combined treatment resulted in profound apoptosis of INA-6 cells even in the presence of BMSCs (Figure 3A-C). To assess if this synergistic effect is dependent on the concentration of the IL-6R antagonist Sant7, we treated INA-6 cells with increasing concentrations of Sant7 either on its own or in combination with PD98059 (50 μM), and with or without coculture with BMSCs. Interestingly, the sensitivity for apoptosis induced by IL-6R blockade was significantly increased if the cells were additionally treated with PD98059 (Figure 3D). The similarity of the results obtained with any combination of pharmacologic inhibitor and/or siRNA strongly supports the assumption that all 4 pathway blockers tested exert their effect on MM cells specifically through the respective pathway.

Treatment of ANBL-6 cells with a combination of Sant7 and PD98059 induces apoptosis in the absence and in the presence of BMSCs

In addition to the INA-6 model, we analyzed the effects of MEK inhibition on the survival of ANBL-6, another IL-6–dependent myeloma cell line. It has previously been shown that in ANBL-6, withdrawal of IL-6 inhibits proliferation and leads to an increase in the number of dead cells over the course of several days.13,21 To confirm this IL-6 dependence, we treated ANBL-6 cells with the IL-6R antagonist Sant7 (50 μg/mL) for 5 days. In contrast to INA-6, blockade of the IL-6R in ANBL-6 did not result in a fast apoptotic response, but in a steady accumulation of apoptotic cells (up to approximately 50%; Figure 5B). Similarly to INA-6, however, cocultivation with BMSCs largely prevented ANBL-6 cells from apoptosis. The combination of Sant7 and PD98059 (50 μM) provoked strong induction of apoptosis in the absence and in the presence of BMSCs (Figure 5B). Again, the concentration of Sant7 was decisive as to what extent cell death was induced (Figure 5C). Notably, treatment of ANBL-6 cells with PD98059 alone led to a small decrease of viable cells (Figure 5B,C). Western blot analysis of components of the IL-6R/STAT3 and the Ras/MAPK pathway revealed that phosphorylation of ERK1,2, but not of STAT3 (Tyr705), was decreased after treatment with PD98059 (Figure 5A). ANBL-6 cells treated with Sant7 displayed a complete lack of phosphorylation of STAT3 (Tyr705). However, the phosphorylation levels of ERK1,2 were only partially decreased by Sant7 (Figure 5A), suggesting that also in ANBL-6 these kinases were activated mainly through IL-6R–independent mechanisms.

Combined treatment of ANBL-6 cells with PD98059 and Sant7 leads to an apoptotic response in the absence and in the presence of BMSCs. (A) Western blots showing the phosphorylation status of ERK1, ERK2, and STAT3 (Tyr705) in ANBL-6 cells cultured for 5 days with or without BMSCs, and with combinations of 50 μM PD98059 and 50 μg/mL Sant7. Staining for ERK1,2 or STAT3 served as loading controls. Low basal levels of ERK phosphorylation were strongly augmented in coculture with BMSCs, and PD98059 effectively inhibited this activation (lanes 6 and 7). Treatment with Sant7 alone entailed a considerable down-regulation as well (lane 8). Sant7 efficiently inhibited IL-6– or BMSC-induced phosphorylation of STAT3 (lane 8). (B) Survival of ANBL-6 cells kept in medium with IL-6 or in coculture with BMSCs, and exposed to combinations of PD98059 (50 μM) and Sant7 (50 μg/mL). PD98059 alone was ineffective, and the 50% reduction in viability achieved with Sant7 was largely lost when the cells were cocultured with BMSCs. The combination of both drugs led to near-complete cell death in both settings. (C) Survival of ANBL-6 cells in medium with IL-6 or in coculture with BMSCs, with or without addition of 50 μM PD98059 and with increasing concentrations of Sant7. Apoptosis was assayed after 5 days. Sant7 was moderately effective at decreasing the viability of ANBL-6 cells, and addition of PD98059 strongly enhanced this effect. Applied alone, PD98059 reduced the viability by some 20%. Data shown are the means of 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis (B) revealed significant (*) or very significant differences (**) as indicated. Error bars denote the range of values derived from at least 3 independent experiments.

Combined treatment of ANBL-6 cells with PD98059 and Sant7 leads to an apoptotic response in the absence and in the presence of BMSCs. (A) Western blots showing the phosphorylation status of ERK1, ERK2, and STAT3 (Tyr705) in ANBL-6 cells cultured for 5 days with or without BMSCs, and with combinations of 50 μM PD98059 and 50 μg/mL Sant7. Staining for ERK1,2 or STAT3 served as loading controls. Low basal levels of ERK phosphorylation were strongly augmented in coculture with BMSCs, and PD98059 effectively inhibited this activation (lanes 6 and 7). Treatment with Sant7 alone entailed a considerable down-regulation as well (lane 8). Sant7 efficiently inhibited IL-6– or BMSC-induced phosphorylation of STAT3 (lane 8). (B) Survival of ANBL-6 cells kept in medium with IL-6 or in coculture with BMSCs, and exposed to combinations of PD98059 (50 μM) and Sant7 (50 μg/mL). PD98059 alone was ineffective, and the 50% reduction in viability achieved with Sant7 was largely lost when the cells were cocultured with BMSCs. The combination of both drugs led to near-complete cell death in both settings. (C) Survival of ANBL-6 cells in medium with IL-6 or in coculture with BMSCs, with or without addition of 50 μM PD98059 and with increasing concentrations of Sant7. Apoptosis was assayed after 5 days. Sant7 was moderately effective at decreasing the viability of ANBL-6 cells, and addition of PD98059 strongly enhanced this effect. Applied alone, PD98059 reduced the viability by some 20%. Data shown are the means of 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis (B) revealed significant (*) or very significant differences (**) as indicated. Error bars denote the range of values derived from at least 3 independent experiments.

Treatment of primary MM cells with Sant7 and PD98059 induces apoptosis in the absence and in the presence of BMSCs

To analyze the survival of primary myeloma cells after treatment with Sant7 and/or PD98059, we cultured MM cells freshly isolated from bone marrow aspirates of 11 patients with 2 ng/mL IL-6 or in the presence of BMSCs, respectively. The primary cells were exposed for up to 7 days to either Sant7 or to PD98059, or to a combination of both (Figure 6, Table 1). The number of viable cells was moderately decreased by treatment with PD98059 to median values of 69% (medium with IL-6) and 78% (BMSCs) of controls. Treatment with Sant7 reduced the number of viable cells to 46% of control in medium with IL-6, but was almost without effect in samples cocultured with BMSCs (87% viable cells). Interestingly, the combined treatment with both drugs led to synergistically induced apoptosis in 10 of 11 patient samples, and reduced viability to 20% (medium with IL-6) and 28% (BMSCs) of controls. The latter data include a sample where PD98059 alone caused strong apoptosis in the presence of BMSCs, which was not enhanced by Sant7. Thus, in primary myeloma cells, too, concomitant pharmacologic blockade of the IL-6R and MEK1,2 efficiently overcomes the resistance to apoptosis imparted by BMSCs.

BMSC-mediated resistance to apoptosis via IL-6R blockade is abolished through concomitant blockade of the MAPK pathway in primary myeloma cells. (A) Survival of primary myeloma cells kept in medium supplemented with 2 ng/mL IL-6 and exposed to combinations of the MEK1,2 inhibitor PD98059 (50 μM) and the IL-6R antagonist Sant7 (50 μg/mL). Treatment with Sant7 reduced viability by about 50%, and the combination of both inhibitors produced a further marked increase in cell death. (B) Survival of primary myeloma cells cocultured with primary BMSCs and exposed to combinations of PD98059 (50 μM) and Sant7 (50 μg/mL). Coculturing had no effect on the slight decrease in myeloma cell viability recorded with PD98059, but it protected the cells from apoptosis induced by Sant7. Combined application of both pathway inhibitors was required to achieve a profound loss of viability in this setting. Myeloma cell preparations from 11 patients were used, and shown are the individual values for the percentage of viable cells after treatment with the respective inhibitor(s). The horizontal lines indicate the median of each treatment cohort. The numerical data are provided in Table 1. Statistical analysis revealed significant (*) or very significant differences (**) as indicated.

BMSC-mediated resistance to apoptosis via IL-6R blockade is abolished through concomitant blockade of the MAPK pathway in primary myeloma cells. (A) Survival of primary myeloma cells kept in medium supplemented with 2 ng/mL IL-6 and exposed to combinations of the MEK1,2 inhibitor PD98059 (50 μM) and the IL-6R antagonist Sant7 (50 μg/mL). Treatment with Sant7 reduced viability by about 50%, and the combination of both inhibitors produced a further marked increase in cell death. (B) Survival of primary myeloma cells cocultured with primary BMSCs and exposed to combinations of PD98059 (50 μM) and Sant7 (50 μg/mL). Coculturing had no effect on the slight decrease in myeloma cell viability recorded with PD98059, but it protected the cells from apoptosis induced by Sant7. Combined application of both pathway inhibitors was required to achieve a profound loss of viability in this setting. Myeloma cell preparations from 11 patients were used, and shown are the individual values for the percentage of viable cells after treatment with the respective inhibitor(s). The horizontal lines indicate the median of each treatment cohort. The numerical data are provided in Table 1. Statistical analysis revealed significant (*) or very significant differences (**) as indicated.

Experimental data obtained with primary MM samples, and general patient characteristics

Experiments . | . | . | Patient characteristics . | . | . | . | . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Percent viable cells . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||||||

| Treatment . | Culture with IL-6 . | Culture with BMSCs . | Age . | Sex . | Stage . | Immunoglobulin type . | Prior chemotherapy . | ||||||

| Patient no. 1 | 58 | Male | III A | IgA (lambda) | AD, HDT-M | ||||||||

| Control | 62 | 67 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 | 46 | 52 | |||||||||||

| Sant7 | 36 | 58 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 + Sant7 | 18 | 25 | |||||||||||

| Patient no. 2 | 70 | Male | III A | Light chain(lambda) | VAD | ||||||||

| Control | 60 | 63 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 | 50 | 54 | |||||||||||

| Sant7 | 42 | 58 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 + Sant7 | 33 | 35 | |||||||||||

| Patient no. 3 | 50 | Male | III A | IgG (lambda) | VAD, MP | ||||||||

| Control | 71 | 67 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 | 44 | 44 | |||||||||||

| Sant7 | 38 | 52 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 + Sant7 | 14 | 13 | |||||||||||

| Patient no. 4 | 57 | Female | III A | IgG (kappa) | VAD, | ||||||||

| Control | 62 | 67 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 | 48 | 57 | VBAM + D, HDT-M | ||||||||||

| Sant7 | 38 | 56 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 + Sant7 | 17 | 22 | |||||||||||

| Patient no. 5 | 59 | Male | III A | IgG (lambda) | No | ||||||||

| Control | 75 | 78 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 | 57 | 66 | (new diagnosis) | ||||||||||

| Sant7 | 25 | 76 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 + Sant7 | 12 | 13 | |||||||||||

| Patient no. 6 | 58 | Male | II A | IgA (lambda) | No | ||||||||

| Control | 70 | 72 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 | 47 | 49 | |||||||||||

| Sant7 | 26 | 68 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 + Sant7 | 10 | 19 | |||||||||||

| Patient no. 7 | 78 | Male | I A | IgA + IgG (kappa) | No | ||||||||

| Control | 77 | 87 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 | 41 | 51 | |||||||||||

| Sant7 | 42 | 74 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 + Sant7 | 19 | 49 | |||||||||||

| Patient no. 8 | 54 | Female | III A | Light chain (kappa) | ID, | ||||||||

| Control | 50 | 51 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 | 50 | 51 | Tandem HDT-M | ||||||||||

| Sant7 | 32 | 52 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 + Sant7 | 16 | 21 | |||||||||||

| Patient no. 9 | 75 | Male | III B | IgA (kappa) | MP, D, Thal | ||||||||

| Control | 90 | 93 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 | 89 | 92 | |||||||||||

| Sant7 | 20 | 90 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 + Sant7 | 7 | 14 | |||||||||||

| Patient no. 10 | 49 | Male | III A | IgG (kappa) | VAD | ||||||||

| Control | 50 | 55 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 | 42 | 41 | |||||||||||

| Sant7 | 23 | 53 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 + Sant7 | 13 | 15 | |||||||||||

| Patient no. 11 | 56 | Female | III A | Nonsecreting | VAD, D | ||||||||

| Control | 71 | 69 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 | 48 | 52 | |||||||||||

| Sant7 | 19 | 53 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 + Sant7 | 9 | 11 | |||||||||||

Experiments . | . | . | Patient characteristics . | . | . | . | . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Percent viable cells . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||||||

| Treatment . | Culture with IL-6 . | Culture with BMSCs . | Age . | Sex . | Stage . | Immunoglobulin type . | Prior chemotherapy . | ||||||

| Patient no. 1 | 58 | Male | III A | IgA (lambda) | AD, HDT-M | ||||||||

| Control | 62 | 67 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 | 46 | 52 | |||||||||||

| Sant7 | 36 | 58 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 + Sant7 | 18 | 25 | |||||||||||

| Patient no. 2 | 70 | Male | III A | Light chain(lambda) | VAD | ||||||||

| Control | 60 | 63 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 | 50 | 54 | |||||||||||

| Sant7 | 42 | 58 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 + Sant7 | 33 | 35 | |||||||||||

| Patient no. 3 | 50 | Male | III A | IgG (lambda) | VAD, MP | ||||||||

| Control | 71 | 67 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 | 44 | 44 | |||||||||||

| Sant7 | 38 | 52 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 + Sant7 | 14 | 13 | |||||||||||

| Patient no. 4 | 57 | Female | III A | IgG (kappa) | VAD, | ||||||||

| Control | 62 | 67 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 | 48 | 57 | VBAM + D, HDT-M | ||||||||||

| Sant7 | 38 | 56 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 + Sant7 | 17 | 22 | |||||||||||

| Patient no. 5 | 59 | Male | III A | IgG (lambda) | No | ||||||||

| Control | 75 | 78 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 | 57 | 66 | (new diagnosis) | ||||||||||

| Sant7 | 25 | 76 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 + Sant7 | 12 | 13 | |||||||||||

| Patient no. 6 | 58 | Male | II A | IgA (lambda) | No | ||||||||

| Control | 70 | 72 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 | 47 | 49 | |||||||||||

| Sant7 | 26 | 68 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 + Sant7 | 10 | 19 | |||||||||||

| Patient no. 7 | 78 | Male | I A | IgA + IgG (kappa) | No | ||||||||

| Control | 77 | 87 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 | 41 | 51 | |||||||||||

| Sant7 | 42 | 74 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 + Sant7 | 19 | 49 | |||||||||||

| Patient no. 8 | 54 | Female | III A | Light chain (kappa) | ID, | ||||||||

| Control | 50 | 51 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 | 50 | 51 | Tandem HDT-M | ||||||||||

| Sant7 | 32 | 52 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 + Sant7 | 16 | 21 | |||||||||||

| Patient no. 9 | 75 | Male | III B | IgA (kappa) | MP, D, Thal | ||||||||

| Control | 90 | 93 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 | 89 | 92 | |||||||||||

| Sant7 | 20 | 90 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 + Sant7 | 7 | 14 | |||||||||||

| Patient no. 10 | 49 | Male | III A | IgG (kappa) | VAD | ||||||||

| Control | 50 | 55 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 | 42 | 41 | |||||||||||

| Sant7 | 23 | 53 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 + Sant7 | 13 | 15 | |||||||||||

| Patient no. 11 | 56 | Female | III A | Nonsecreting | VAD, D | ||||||||

| Control | 71 | 69 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 | 48 | 52 | |||||||||||

| Sant7 | 19 | 53 | |||||||||||

| PD98059 + Sant7 | 9 | 11 | |||||||||||

Overview of the individual responses of primary myeloma cells to treatment with PD98059 (50 μM) and/or Sant7 (50 μg/mL). The numbers represent the percentage of viable cells after treatment with the respective drug or drugs. Myeloma cell preparations from 11 patients were kept either in medium supplemented with 2 ng/mL IL-6, or in coculture with primary BMSCs, and were assayed for apoptosis after 5 to 7 days. Some general information regarding the patients and their treatment is included.

VAD indicates vincristine, doxorubicine, dexamethasone; MP, melphalan, prednisone; D, dexamethasone; VBAM, vincristine, bendamustine, doxorubicine, melphalan; ID, idarubicine, dexamethasone; HDT-M, high-dose therapy melphalan; Thal, thalidomide.

Discussion

We have recently demonstrated that MM cells are protected from apoptosis triggered by blockade of the IL-6R, if they are cocultured with BMSCs.19 This result suggested that the BM microenvironment supports the activation of signaling pathways that might substitute for the antiapoptotic function of IL-6R–mediated STAT3 activation. We suspected involvement of the MEK1,2/ERK1,2 module because the strongly enhanced phosphorylation of ERK1,2 in cocultured cells could not be curbed through IL-6R blockade. Activation of this pathway is important for cell proliferation in many experimental systems. This has also been reported in MM, although exclusively in conjunction with IL-6 dependence.12 It has recently been found that activation of ERK1,2 can mediate survival in some types of cancer.25,26 However, it is currently unclear if activation of the MEK1,2/ERK1,2 module has an impact on the survival of MM cells.

In this study, we have employed IL-6–dependent MM cell lines and primary MM cells in coculture with BMSCs to investigate the function of the MEK1,2/ERK1,2 module, and of the transcription factor STAT3, for the growth and survival of MM cells. Through the use of pharmacologic inhibitors and expression constructs for siRNAs, we were able to assess the effects of single and combined pathway blockade by 2 independent approaches, and at different levels of the respective signaling cascade, in the cell line INA-6. The results obtained with this line were corroborated with the cell line ANBL-6, and with primary MM cells.

siRNA technology is a powerful new approach to specifically extinguish single proteins within signaling cascades. It thus complements analyses with small compound inhibitors, which may additionally affect other targets and can therefore display unexpected and unspecific side effects that may be difficult to interpret.27 An important advantage of siRNA expression over treatment with pharmacologic inhibitors is restriction of the manipulation to the transfected cells, which is relevant for any coculture experiments with BMSCs. In our hands, the INA-6 MM cell line proved an efficient model for transient transfection by electroporation. This is of general interest, because MM cell lines are usually hard to transfect. The possibility to generate bulk quantities of highly purified manipulated cells makes INA-6 ideally suited for signal transduction analyses.

Our data demonstrate that targeting the mRNAs for ERK1, ERK2, or STAT3 strongly diminished the levels of the respective proteins. Consequently, very little active (phosphorylated) protein remained detectable even after strong induction of the corresponding pathway. Because siRNAs may lead to unspecific side effects too,28 it is noteworthy that in all cases no effect on the levels of any but the targeted proteins was observed in Western blots. Importantly, the biologic effects from siRNA knockdown in INA-6 cells matched those of pharmacologic blockade of the same pathway. Thus, similar results were obtained with ERK1,2 siRNA knockdown or inhibition of MEK1,2 with PD98059. This supports the notion that the effects on apoptosis and proliferation seen with either approach are indeed mediated through the MEK1,2/ERK1,2 module. The effects of STAT3 knockdown matched those of IL-6R blockade with Sant7, and we explicitly validated the specificity of STAT3 siRNA-mediated apoptosis with an expression plasmid for STAT3 protein, in which the target sequence within the gene was modified through silent mutations. Notably, induction of apoptosis through combined pathway blockade was confirmed by 2 independent combinations of pharmacologic inhibitor and siRNA. This underscores the specificity of the effect seen in the ANBL-6 cell line and in primary MM cells, which could not be efficiently transfected.

In accordance with other reports on MM cell lines, we found that in the absence of BMSCs the proliferation of INA-6 cells was partially impaired by PD9805913,14,20 or expression of ERK1,2 siRNAs, whereas only minor effects were observed for cocultured cells. Furthermore, in the presence of BMSCs, inhibition of a single pathway was ineffective and concomitant inhibition of signaling through the IL-6R/STAT3 pathway and the MEK1,2/ERK1,2 module was required to efficiently induce apoptosis of MM cells. These results demonstrate for the first time that the ERK1,2/MEK1,2 module influences apoptotic responses of MM cells, although the precise mechanism currently remains unclear. Additionally, our pharmacologic and siRNA data demonstrate that no significant crosstalk exists between these 2 pathways. Down-regulation of ERK1,2 activity in INA-6 cells, by siRNA or by PD98059 treatment, did not interfere with phosphorylation of STAT3 at Tyr705 or at Ser727. In contrast to previous reports,12 we find that even in IL-6–dependent MM cell lines the activation of ERK1,2 is mediated mainly via IL-6R–independent mechanisms. Thus, the strong up-regulation of the ERK1,2 phosphorylation in INA-6 and ANBL-6 cells upon contact with BMSCs was not (INA-6 cells) or just partially (ANBL-6 cells) affected by Sant7. These findings suggest that in addition to IL-6 other BMSC-derived factors and/or adhesion-mediated processes are involved in the activation of ERK1,2.

It has recently been shown that the prevention of STAT3 binding to mutated chimeric IL-6Rβ constructs correlated with apoptosis of INA-6 cells, whereas binding of SHP-2 (which links IL-6Rβ signaling to the MAPK pathway) was not affecting survival.29 Here, we show unequivocally that STAT3 protein is essential to prevent apoptosis of INA-6 cells in the absence of BMSCs, indicating that the dependence of INA-6 cells on IL-6 is crucially mediated by STAT3 rather than by MAPK activation.

Taken together, our observations suggest that in the presence of BMSCs different mechanisms are responsible for the activation of ERK1,2 and STAT3 in MM cells. The activation of STAT3 is mainly induced by IL-6, whereas phosphorylation of ERK1,2 is mediated at least partially via IL-6–independent mechanisms. Accordingly, we and others have previously reported that several BMSC-derived factors, such as macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha,30 vascular endothelial growth factor,31 IL-1β, and stromal cell–derived factor 1 alpha,32 may activate ERK1,2 in MM cells, whereas activation of STAT3 is exclusively triggered via IL-6Rβ by cytokines of the IL-6 family. The mutual compensation for the loss of the pro-survival effect that is mediated by these pathways suggests that in the BM microenvironment STAT3 and ERK1,2 contribute independently to the survival of MM cells. This model might provide an explanation for the observation that the IL-6R/STAT3 pathway is dispensable for MM cells that are cocultured with BMSCs.

In view of the rather frequent activating mutations of N-Ras and K-Ras2 that distinguish MM from monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance,33 it has been suggested that these aberrations can contribute to the IL-6–independent growth of MM cells. Transfection studies have shown that the overexpression of activating Ras mutants in the ANBL-6 MM cell line rendered these cells IL-6 independent.34,35 This work suggests that oncogenic Ras can contribute to malignant growth without input via IL-6R–triggered signal transduction. However, although the INA-6 MM cell line contains an endogenous activating N-Ras mutation,20 its survival in the absence of BMSCs is strictly dependent on IL-6. Furthermore, coculture with BMSCs renders INA-6 as well as ANBL-6 cells (which contain wild-type Ras) IL-6 independent. The strong increase of phosphorylated ERK1,2 is a common feature in both of the above-mentioned MM models. This clearly indicates that up-regulation of ERK activity mediated by BMSCs rather than Ras mutations contributes to IL-6–independent growth of MM cells.

Treatment of MM cells with the FTI, farnesyl transferase inhibitor, FPTIII was shown to induce apoptosis even in the presence of BMSCs.19 However, our current data demonstrate that selective elimination of either MEK1,2 or ERK1,2 activity was not sufficient to induce apoptosis of MM cells, excluding a causative role of the MEK1,2/ERK1,2 module for the apoptosis of FTI-treated cells, and underpinning the value of pathway analyses at different levels and with highly selective tools.

A third major signaling system that has been reported to contribute to the promotion of growth and survival in myeloma cells is the PI3-kinase/Akt pathway.36,37 Blockade of this pathway was shown to curb growth and to induce apoptosis of MM cell lines in vitro,38 although these effects have yet to be confirmed in the presence of BMSCs. Furthermore, the Akt homologs represent just one branch of antiapoptotic signaling downstream of PI3K.39 However, it is tempting to speculate that the combined disruption of different and simultaneously active signaling pathways (eg, IL-6R/STAT3, MAPK, PI3K/Akt) provides an effective approach for the development of novel and better treatment strategies for MM.

We have recently shown that IL-6–dependent myeloma cells become independent of the IL-6R/STAT3 pathway if they are cocultured with BMSCs. In this paper we present for the first time the biochemical mechanism that mediates this important prosurvival effect. With a combination of genetic and pharmacologic approaches, we clearly demonstrate that the strong BMSC-mediated up-regulation of the MEK/ERK pathway is achieved mainly in an IL-6–independent manner, and that this is the mechanism through which BMSCs relieve myeloma cells from their requirement for IL-6R/STAT3 signaling. Consequently, combined disruption of both pathways is required to induce apoptosis of myeloma cells in the presence of BMSCs. Furthermore, these data demonstrate for the first time that the MEK1,2/ERK1,2 module, in addition to its previously described role in cell proliferation, can critically influence the survival of MM cells. These observations are in good accordance with the lack of an objective clinical response in a phase 1 study conducted with an anti–IL-6 monoclonal antibody as monotherapy.40 However, our data underscore that the combined blockade of IL-6R–dependent and –independent signaling pathways could be a promising therapeutic strategy for MM.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, August 5, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1670.

Supported in parts by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Klinische Forschergruppe KFO 105).

M.C. and T.S. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank M. Gramatzki, A. Günther, and F. Bakker (Erlangen, Germany) for provision of the INA-6 cell line and for helpful discussion.

![Figure 4. Effects of IL-6R/STAT3 and MAPK pathway blockade on the proliferation of INA-6 cells. (A) INA-6 cells transfected with expression plasmids for siRNAs against ERK1 and ERK2 (pSU-ERK1 + 2) or with control plasmid (pSU), and untransfected cells treated with PD98059, were cultured in medium with IL-6 (left) or in the presence of BMSCs (right) and their proliferation assayed after 3 days. Proliferation (ie, incorporation of [3H]-thymidine) was very similar for cells cultured in medium or on BMSCs with a less than 20% difference in total counts. Within each experimental set the proliferation of unmanipulated cells was arbitrarily set as 100%. Blockade of MEK1,2/ERK1,2 signaling slightly reduced proliferation in both settings. (B) INA-6 cells transfected with an expression plasmid for an siRNA against STAT3 (pSU-STAT3) or with control plasmid (pSU), and untransfected cells treated with Sant7, were cultured in medium with IL-6 (left) or in the presence of BMSCs (right). In keeping with extensive cell death, Sant7 and the siRNA abrogated all proliferation in medium, but proliferation with either treatment was only moderately reduced in the presence of BMSCs. (C) Confirmation of the specificity of STAT3 siRNA-mediated cell death. Expression of STAT3 protein that is derived from a sequence no longer recognizable by the siRNA (plasmid pS3R) largely offset the detrimental effects of STAT3 siRNA expression on the proliferation of INA-6 cells. All data shown are derived from at least 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis (A,B) revealed very significant (**), significant (*), or no (n.s. = not significant) differences as indicated. Error bars denote the range of values derived from at least 3 independent experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/104/12/10.1182_blood-2004-04-1670/5/m_zh80230470030004.jpeg?Expires=1767777236&Signature=jXSdR3WAQFSHqJm3ojp~JEo0btYJLBKc~K42Ss4C4PPiCcgYlZTnhIZTDgftgwXJhYA-KzSUykX2zGYqjaiFCAFzBygkI6ouSejmq7cH7Vnl206rPoslr2PhOyd8j5WPldVM2NpO2CsyUp9xLgIs4VOCeXmT79T~imcoVztH7HM~0iS5IL~iD80KBaA3y37PqR6qftS74bdV2l0OjeiIWVa5IXziZTpIAHwUtsq-gxt1wkUwK2izyG2tccgiSkZrtexhRxKFxUxwj~vv2QSTFmSEeLQRQ3Iwdn-N5zh1GKAlsv9qwtct53ZmnFhYNS~nQcu2gaLLqa1UD2EpgEbsaw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal