Abstract

Primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMBL), currently recognized as a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) subtype, shows increased expression of interleukin 4 (IL-4)/IL-13 signaling effectors and targets, suggesting constitutive activation of these pathways. We therefore investigated the functional state of the signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6), mediating IL-4/IL-13 transcriptional effects. Constitutive STAT6 phosphorylation and DNA-binding activity were detected in PMBL cell lines but not DLBCL cell lines. Moreover, immunohistochemical analysis revealed nuclear phosphorylated STAT6 (P-STAT6) in 8 of 11 PMBL, compared with 1 of 10 DLBCL primary tumors (P = .01). IL-4 and IL-13 transcripts were absent in PMBL cell lines and expressed at low levels in tumors, indicating that, contrary to classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL), STAT6 activation is not due to an autocrine IL-4/IL-13 secretion. We demonstrated an amplification of the JAK2 gene in 2 of 6 PMBL cases, and showed higher JAK2 mRNA levels in PMBL compared with DLBCL (P = .005). The Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) was constitutively phosphorylated in the PMBL MedB1 cell line. MedB1 treatment with JAK2 inhibitor AG490 partially decreased STAT6 phosphorylation, suggesting that JAK2 is partially involved in STAT6 activation in these cells. Our findings highlight phosphorylated STAT6 as a characteristic distinguishing PMBL from DLBCL, but a common feature to PMBL and cHL, supporting the hypothesis of common pathogenic events in these 2 lymphomas. (Blood. 2004;104: 543-549)

Introduction

Primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMBL) has been recognized as a specific subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) with unique clinical, histologic, and biologic features.1 It accounts for about 5% of aggressive lymphomas, with a 50% to 60% 5-year failure-free survival rate despite intensive chemo-therapy. This lymphoma presents as a mediastinal mass consisting of large B cells that usually express little if any surface or cytoplasmic immunoglobulin and major histocompatibility complex class I and/or class II molecules and presumably derive from a subset of thymic B cells.2 Molecular diagnostic markers that can distinguish PMBL from DLBCL with mediastinal involvement have only very recently been identified.3-6 Moreover, transcriptional profiling of PMBL also revealed that this lymphoma subtype shares some features with classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL).5,6 In this regard, it is interesting that some cases, referred to as gray zone lymphoma of the mediastinum, show borderline features between PMBL and cHLs, making these tumors exceedingly difficult to discriminate.2

We have recently identified several genes specifically expressed in PMBL in comparison with DLBCL, including MAL3,7 and FIG1/IL-4I1 (interleukin 4-induced gene 1).4 This latter gene, which encodes a protein containing a flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)-binding amino oxidase domain, is tightly regulated in response to interleukin 4 (IL-4) treatment.8,9 In aggressive large B-cell lymphoma, it has been suggested that specific antigenic stimulation plays a role at an early stage in the pathogenesis, but that such stimulation is ultimately unnecessary due to the acquisition of aberrant internal cellular signaling mechanisms.10 Cytokine pathway activation has been demonstrated in lymphomas, in particular IL-13 secretion in cHL.11,12 Transcriptional analysis of PMBL recently demonstrated increased expression of the IL-13 receptor α1 chain (IL-13Rα1), JAK2, and several IL-4/IL-13-dependent (CD23, NF-IL3, FIG1/IL-4I1) genes,4-6 suggesting constitutive activation of the IL-4/IL-13 pathway(s) in these tumors. IL-4 and IL-13 share many biologic functions, including the ability to act as a costimulant in B-cell proliferation as well as to induce immunoglobulin class switch. IL-4 and IL-13 also share part of their intracellular signal transduction pathways leading to gene activation. There are 2 receptors for IL-4 that have been described: type I, composed of the IL-4Rα chain in association with the γ common chain; and type II, consisting of the same IL-4Rα chain in association with the IL-13Rα1 chain. While the first type binds only IL-4, the second can bind either of the 2 cytokines. Ligand-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of these receptors by receptor-associated Janus kinases (JAKs)13,14 creates receptor-docking sites for recruitment of cytoplasmic signal transducer and activators of transcription (STATs) proteins as well as the insulin receptor substrate 2 adapter. STAT6 is the transcription factor primarily activated by IL-4 and IL-13 stimulation and is mainly responsible for their transcriptional effects. Upon recruitment to specific phosphorylated receptor sites through its C-terminal Src homology 2 (SH2) domain, STAT6 is phosphorylated on Tyr641 and hence activated. In its activated form, STAT6 protein dimerizes and translocates to the nucleus where it can bind to Stat regulatory elements and regulate transcription in association with other transcription factors.

We have hypothesized that FIG1/IL-4I1 expression could reflect the activation of the IL-4/IL-13 pathway(s) in PMBL. Our results demonstrate that STAT6 is constitutively activated in PMBL but not in DLBCL, and that, in contrast to cHL, this activation is not due to IL-13 gene expression. Our data show that the JAK2 gene is amplified and overexpressed in PMBL, and suggest that JAK2 kinase activation is partially involved in STAT6 activation in the MedB1 cell line.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and other reagents

Anti-JAK1, anti-JAK2, anti-JAK3, and anti-P-tyrosine (anti-P-Tyr) clone 4G10 antibodies were purchased from Upstate Biotechnology (Charlottesville, VA). Anti-phosphorylated STAT6 (P-STAT6) antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Anti-STAT6 antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Recombinant human IL-4 and IL-13 were purchased from R&D System Europe (Lille, France). Enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (ECL) was purchased from Amersham Bioscience (Orsay, France).

Cell lines

The cell lines derived from PMBLs, MedB1 (kind gift of P. Möller, University of Ulm, Ulm, Germany) and Karpas 1106 (kind gift from M. Dyer, University of Leicester, Leicester, United Kingdom) have been described previously.15,16 The DLCBL-derived B-cell lines, characterized as activated B cells (OCI-Ly3, OCI-Ly10) and germinal center cells (SUDHL4 and SUDHL6)17 were a kind gift from Dr L Staudt (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). The L428 cHL cell line was a generous gift of Prof G. Delsol (INSERM U-563, Centre de Physiopatholgie de Toulouse-Purpan, France). All cell lines were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere in Iscove medium supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 10 U/mL penicillin, and 10 μg/mL streptomycin. UT7 transfected cells expressing the thrombopoietin receptor (UT7mpl) were used as controls and were activated by a 30-minute treatment in the presence of 10 nM thrombopoietin (TPO), as described previously.18

Tissue specimens

Biopsy specimens of PMBL (n = 26), DLBCL (n = 26), nodular sclerosis cHL (n = 5), and reactive lymph nodes (n = 4) were retrieved from the files of the department of Pathology, Hôpital Henri Mondor, Créteil, France. All patients with PMBL presented an initial prominent bulky mediastinal mass. The morphologic features were assessed on hematoxylin-eosin-stained sections of fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue. All cases were evaluated for B- and T-cell differentiation antigens. Diagnosis of each case was established by combined histologic and immunohistochemical criteria, and the lymphomas were classified according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification.1 Formalin-fixed specimens were used for immunohistochemical detection of P-STAT6 protein, and frozen specimens were used for Southern blot and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) studies.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry for P-STAT6 was performed on deparaffinized, formalin-fixed tissue sections using an indirect immunoperoxidase method with an automated immunostainer (Ventana medical system, Tucson, AZ). Briefly, after appropriate antigen retrieval with microwave heating (12 minutes at 750 W and 3 cycles of 5 minutes at 350 W) in high pH Target Retrieval Solution (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), tissue sections were incubated for 30 minutes with anti-P-STAT6 antibody diluted 1:100 and then with the appropriate immunoperoxidase detection kit (Ventana medical system) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. For the evaluation of P-STAT6 staining, cases were considered positive if at least 10% of the malignant cells demonstrated nuclear staining, according to a recent report.19 Images were acquired using an Olympus BX51 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with objective lenses UPlan F1 (100 ×/1.30 oil, Olympus) equipped with a Camedia digital camera C3030 zoom (Olympus) and Camedia MAFP-2NE software (Olympus).

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis

Total RNAs were isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Cergy Pontoise, France). Total RNAs (2 μg) were reverse transcribed with Superscript II (Invitrogen) in a final volume of 20 μL containing 300 ng random hexamers, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Following enzyme heat inactivation, cDNAs were diluted 1:5 in water and stored at -20°C. IL-4, IL-13, and JAK2 mRNA levels were measured by real-time quantitative RT-PCR using the Light Cycler (Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France) SYBR Green or FRET technology, and normalized to housekeeping GAPDH and S14 mRNAs values to control for RNA quality and reverse-transcription efficiency. For each real-time PCR run, cDNAs were run in duplicate, in parallel with 8 quantitative DNA standard dilution samples. PCR reactions were performed in Light Cycler capillaries, in a 20-μL volume containing 2 μL cDNAs diluted 1:3 (corresponding to 13 ng RNA), 2 μL Light cycler-FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I or Hybridization Probe mix (Roche Diagnostics), 4 mM final MgCl2 concentration, and 0.2 to 0.5 μM sense and antisense specific primers. The following primers were used: GAPDH sense, 5′-GGATTTGGTCGTATTGGGCGC-3′ and GAPDH antisense, 5′-GTTCTCAGCCTTGACGGTGC-3′; GAPDH FRET probes, AACTCTGGTAAAGTGGATATTGTTGCCATCAATGAC-fluo and Red640-CCTTCATTGACCTCAACTACATGGTTTACATGTTCC; IL-4 sense, 5′-TTCTCCTGATAAACTAATTGCCTCACATTGTC-3′ and IL-4 antisense, 5′-GGTGATATCGCACTTGTGTCCGTGG-3′; IL4 FRET probes, TCTCACCTCCCAACTGCTTCCCCCTCTGT-fluo and Red640-CTTCCTGCTAGCATGTGCCGGCAACTTTGT; IL-13 sense, 5′-GCTCTCACTTGCCTTGGCGGCT-3′ and IL-13 antisense, 5′-TCAGCATCCTCTGGGTCTTCTCGATG-3′; IL13 FRET probes, ATGGTATGGAGCATCAACCTGACAGCTGGCA-fluo and Red640-TACTGTGCAGCCCTGGAATCCCTGATCAAC; JAK2 sense, 5-TCTTGGGATG-GCAGTGTTAGA-3′ and JAK2 antisense, 5′-AATCTGCGAAATCTGTACCTT-3′; and S14 sense, 5′-GGCAGACCGAGATGAATCCTCA-3′ and S14 antisense, 5′-CAGGTCCAGGGGTCTTGGTCC-3′.

DNA extraction and Southern blot analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from 6 PMBL and 4 DLBCL tumor samples by proteinase K digestion, phenol/chloroform extraction, and ethanol precipitation. Southern blots of EcoRI digested DNAs were hybridized with a α-32P-labeled 1.8-kb intronic JAK2 probe (kind gift of O. Bernard, INSERM EMI 0210, Paris, France) and a α-32P-labeled 0.9-kb β-globin exon 3 probe (106 cpm/mL each).

Protein extraction, immunoprecipitation, and Western blotting

For preparation of total cell lysates, cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed on ice for 5 minutes in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris [tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane]-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA [ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid], 1% Triton X100) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete Protease Inhibitors; Roche Diagnostics), 50 mM NaF, and 1 mM Na3VO4. After clearing the samples at 5000g for 5 minutes at 4°C, proteins were quantified by the BioRad protein Assay (Hercules, CA) using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as standard. Equal amounts of proteins (10 μg/lane) were loaded on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels or used for immunoprecipitation followed by SDS-PAGE. Immunoprecipitation was performed on 500 μg of total proteins by adding anti-JAK1, anti-JAK2, or anti-JAK3 antibodies overnight at 4°C. Protein G-Sepharose (Amersham Bioscience) was used to precipitate the immune complex for 2 hours at 4°C. Immunoprecipitated proteins were washed, and recovered by boiling in Laemmli sample buffer. Proteins separated by SDS-PAGE were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes at 100 V for 90 minutes in transfer buffer (20 mM Tris, 150 mM glycine, 20% ethanol) and probed with the appropriate antibodies, followed by ECL (Amersham Bioscience) revelation.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Nuclear extracts were prepared as previously described20 and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C before use. Extracts (10 μg) were incubated with 16 pmol 32P-labeled β-casein promoter derived probe (5′-AGATTTCTAGGATTCAAATC-3′) and separated on a 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel. For supershift assay, nuclear extracts were incubated with 0.2 μg anti-STAT6 antibody and the probe.

AG490 treatment

Tyrphostin AG490 from Upstate Biotechnology was diluted in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Cell lines were seeded at 0.4 to 0.6 × 105 cells/mL and treated for 24 hours with 50 μM AG490. Control cells were treated with equal volumes of DMSO. After treatment, cells were washed in PBS and cell extracts prepared as described in “Protein extraction, immunoprecipitation, and Western blotting.”

Statistical analysis

To test the differences between PMBL and DLBCL, we compared nuclear P-STAT6 staining with a Chi2 test, and JAK2/S14 mRNA ratios with a Mann Whitney U test (Statview software; Abacus concepts, Berkeley, CA).

Results

IL-4/IL-13 gene expression in PMBL

To determine whether the expression of IL-4/IL-13-dependent genes in PMBL is due to autocrine or paracrine secretion of these cytokines in the tumor, we measured the levels of IL-4 and IL-13 messenger RNA in 8 PMBL and 8 DLBCL samples using quantitative RT-PCR. Very low levels of IL-4 transcripts, similar to those observed in reactive lymph nodes, were found in both types of lymphomas (Figure 1A), most probably representing infiltrating reactive cells in the tumor. IL-13 transcripts were absent in all samples (PMBL, DLBCL, reactive lymph nodes) with the exception of one PMBL case that presents peculiar cytolologic features with large pleomorphic cells with multilobated nuclei. IL-4 and IL-13 transcripts were also absent in the 2 PMBL- and 4 DLBCL-derived B-cell lines studied as well as in Ramos, a Burkitt-derived cell line, but expressed at high levels in the L428 Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) cell line as previously described12 (Figure 1B). Taken together, these data indicate that the expression of the FIG1/IL-4I1 gene in PMBL is not due to autocrine or paracrine secretion of IL-4 and/or IL-13.

IL-4 and IL-13 mRNA expression in PMBL. (A) IL-4 (▴) and IL-13 (▵) transcript levels were measured by quantitative RT-PCR in reactive lymph nodes (n = 4), PMBL (n = 8), and DLBCL (n = 8) samples as reported in “Materials and methods.” Results are expressed as IL-4/IL-13 copy number per 106 copies of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Bars indicate the median and interquartile values. (B) IL-4 and IL-13 transcript levels were measured by quantitative RT-PCR as in panel A in various lymphoma-derived B-cell lines.

IL-4 and IL-13 mRNA expression in PMBL. (A) IL-4 (▴) and IL-13 (▵) transcript levels were measured by quantitative RT-PCR in reactive lymph nodes (n = 4), PMBL (n = 8), and DLBCL (n = 8) samples as reported in “Materials and methods.” Results are expressed as IL-4/IL-13 copy number per 106 copies of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Bars indicate the median and interquartile values. (B) IL-4 and IL-13 transcript levels were measured by quantitative RT-PCR as in panel A in various lymphoma-derived B-cell lines.

STAT6 activation in PMBL-derived cell lines

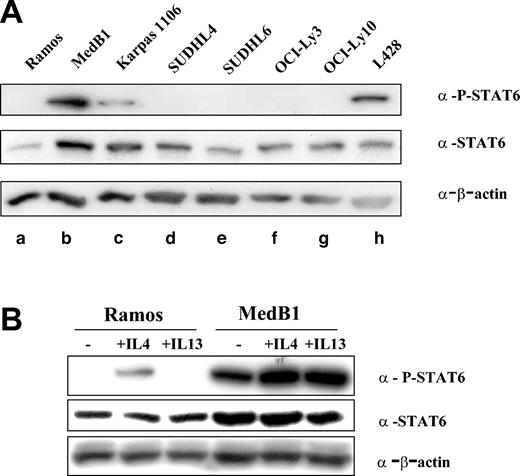

FIG1/IL-4I1 gene activation has been shown to be dependent on the signalization and transcription factor STAT6.21 In order to determine whether STAT6 is activated in PMBL, we performed Western blot analysis on total cell protein extracts using specific anti-P-STAT6 (Tyr 641) antibody (Figure 2A). P-STAT6 was detected in only 3 cell lines: the HL-derived L428, as already reported,19 and the 2 PMBL-derived cell lines, MedB1 and Karpas 1106. While expressing STAT6, the DLBCL cell lines did not show any evidence of STAT6 phosphorylation. STAT6 phosphorylation in MedB1 cells was also detected in cells grown in serum-free medium (data not shown) and was further enhanced by IL-4 or IL-13 treatment, while only IL-4 induced P-STAT6 in Ramos cells, because of the absence of IL-13α1 receptor in Burkitt-derived cells22 (Figure 2B).

STAT6 phosphorylation in PMBL-derived cell lines. (A) Cell lysates were prepared from one Burkitt lymphoma-derived cell line (a: Ramos), 2 PMBL-derived cell lines (b: MedB1 and c: Karpas 1106), 4 DLBCL-derived cell lines (d: SUDHL4, e: SUDHL6, f: OCI-Ly3, and g: OCI-Ly10), and 1 Hodgkin-derived cell line (h: L428). Equal amounts of whole cell lysate were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis. Phosphorylated STAT6 was identified using phosphospecific antibody for Tyr641 phosphorylated STAT6. Blots were stripped and reprobed with an anti-STAT6 antibody. As a loading control, blots were probed with anti-β-actin antibody. (B) Ramos and MedB1 cells were treated for 10 minutes with 10 ng/mL IL-4 or 5 ng/mL IL-13, or left untreated (-) and samples prepared and analyzed as in panel A.

STAT6 phosphorylation in PMBL-derived cell lines. (A) Cell lysates were prepared from one Burkitt lymphoma-derived cell line (a: Ramos), 2 PMBL-derived cell lines (b: MedB1 and c: Karpas 1106), 4 DLBCL-derived cell lines (d: SUDHL4, e: SUDHL6, f: OCI-Ly3, and g: OCI-Ly10), and 1 Hodgkin-derived cell line (h: L428). Equal amounts of whole cell lysate were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis. Phosphorylated STAT6 was identified using phosphospecific antibody for Tyr641 phosphorylated STAT6. Blots were stripped and reprobed with an anti-STAT6 antibody. As a loading control, blots were probed with anti-β-actin antibody. (B) Ramos and MedB1 cells were treated for 10 minutes with 10 ng/mL IL-4 or 5 ng/mL IL-13, or left untreated (-) and samples prepared and analyzed as in panel A.

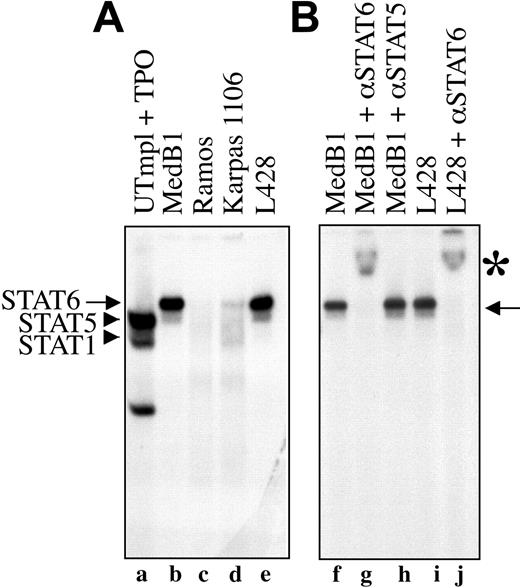

To provide further evidence that STAT6 is constitutively activated in PMBL-derived cell lines, we tested the ability of nuclear proteins of different cell lines to bind STAT6 consensus DNA binding sequence in electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) using a STAT responsive element from the β-casein promoter as probe. As shown in Figure 3A, nuclear extracts from the 2 PMBL-derived cell lines (MedB1 and Karpas 1106) and the HL-derived cell line (L428) formed a complex with the probe (arrows, lanes b,d-e) that was competed with an excess of cold probe (data not shown). This complex migrated differentially compared with STAT5 and STAT1 dimers activated by thrombopoietin in control cells (lane a). It was entirely supershifted by incubation with anti-STAT6 antibody (Figure 3B, lanes g,j) but not with anti-STAT5 (lane h) or anti-STAT1 antibodies (data not shown), indicating the presence of active and functional STAT6 in the DNA-bound complex. The diffuse and weak band that migrated ahead of the STAT6 complex was not reproducibly observed in all experiments. It was still supershifted with anti-STAT6 antibody and may represent a STAT6 proteolytic fragment. The amount of STAT6-DNA complex was always lower in Karpas 1106 than in MedB1 cells, in agreement with the level of phosphorylation of STAT6 in these 2 cell lines. As expected from the study of STAT6 phosphorylation, no STAT6-DNA complex was observed in Ramos (Figure 3A, lane c) and DLBCL-derived (data not shown) cell lines.

STAT6 activation in PMBL-derived cell lines. (A) Nuclear extracts were prepared from control cells (UT7mpl treated with 10 nM TPO for 30 minutes), PMBL-derived cell lines (MedB1 and Karpas 1106), the Hodgkin-derived cell line (L428), and the Burkitt-derived cell line (Ramos), and were assayed in EMSA using the β-casein responsive element as probe. To get better resolution of the DNA-protein complex, the probe was run out of the gel. (B) Where indicated, anti-STAT6-specific antibody was added to the binding reaction. Arrows indicate STAT6-DNA complexes; arrowheads indicate STAT1 and STAT5 complexes. *STAT6 supershifted complexes.

STAT6 activation in PMBL-derived cell lines. (A) Nuclear extracts were prepared from control cells (UT7mpl treated with 10 nM TPO for 30 minutes), PMBL-derived cell lines (MedB1 and Karpas 1106), the Hodgkin-derived cell line (L428), and the Burkitt-derived cell line (Ramos), and were assayed in EMSA using the β-casein responsive element as probe. To get better resolution of the DNA-protein complex, the probe was run out of the gel. (B) Where indicated, anti-STAT6-specific antibody was added to the binding reaction. Arrows indicate STAT6-DNA complexes; arrowheads indicate STAT1 and STAT5 complexes. *STAT6 supershifted complexes.

STAT6 activation in PMBL primary tumors

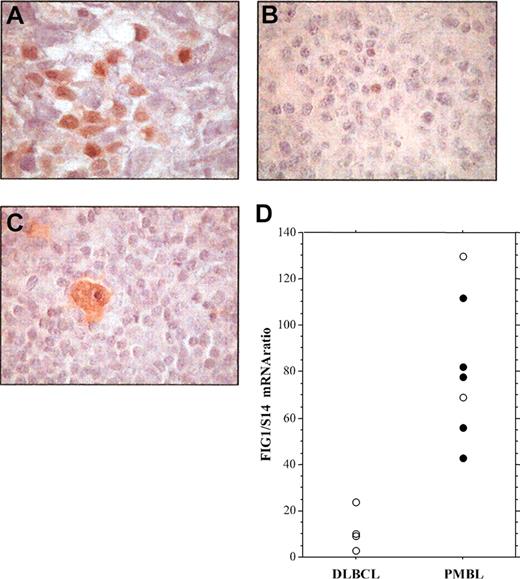

To investigate the presence of activated STAT6 in primary PMBL, we performed immunohistochemical analysis of P-STAT6 on formalin-fixed tumor specimens from cHL, nonmediastinal DLBCL, and PMBL patients (Figure 4; Table 1). In PMBL samples, P-STAT6 staining was often heterogeneous and the number of positive cells ranged from 10% to 50% of the neoplastic cells (Figure 4A; Table 1). As a control, expression of P-STAT6 protein was also investigated on tissue samples of 5 nodular sclerosis cHLs, 4 of which showed strong expression of activated STAT6 within most Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells (Figure 4C; Table 1) as previously reported.19 P-STAT6 was detected in the nuclei of neoplastic cells in 8 (73%) of the 11 PMBL (Table 1), but in only 1 (10%) among the 10 nonmediastinal DLBCL cases (Chi2, P = .01). FIG1/IL4I1 gene expression was investigated in some cases. As shown in Figure 4D, FIG1/IL4I1 gene expression was high in the 5 P-STAT6-positive PMBL cases, but low in the 4 P-STAT6-negative DLBCL cases. There were 2 PMBL cases that displayed high FIG1/IL4I1 expression in the absence of detectable STAT6 phosphorylation, suggesting that other transcription factors might regulate FIG1/IL4I1 gene expression.

Immunohistochemical detection of phosphorylated STAT6 protein in specimens of PMBL, DLBCL, and cHL. (A) Staining for nuclear P-STAT6 was demonstrated in neoplastic cells of PMBL. (B) In nonmediastinal DLBCL, neoplastic cells were negative for P-STAT6 with only a few scattered reactive cells being positive. (C) HRS cells of cHL disclosed strong staining for P-STAT6. (D) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of FIG1/IL4I1 gene expression in 4 DLBCL and 7 PMBL samples showing either positive (•) or negative (○) P-STAT6 immunostaining, original magnification, × 100.

Immunohistochemical detection of phosphorylated STAT6 protein in specimens of PMBL, DLBCL, and cHL. (A) Staining for nuclear P-STAT6 was demonstrated in neoplastic cells of PMBL. (B) In nonmediastinal DLBCL, neoplastic cells were negative for P-STAT6 with only a few scattered reactive cells being positive. (C) HRS cells of cHL disclosed strong staining for P-STAT6. (D) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of FIG1/IL4I1 gene expression in 4 DLBCL and 7 PMBL samples showing either positive (•) or negative (○) P-STAT6 immunostaining, original magnification, × 100.

Immunohistochemical analysis of phosphorylated STAT6 protein expression in lymphomas

Case no. . | Diagnosis . | Sex and age, y . | Site . | P-STAT6 staining . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PMBL | F, 33 | Med | ++ |

| 2 | PMBL | F, 57 | Med | − |

| 3 | PMBL | F, 40 | Med | ++ |

| 4 | PMBL | M, 62 | Med | − |

| 5 | PMBL | F, 54 | Med | ++ |

| 6 | PMBL | M, 27 | Med | + |

| 7 | PMBL | M, 66 | Med | + |

| 8 | PMBL | F, 23 | Med | + |

| 9 | PMBL | F, 37 | Med | − |

| 10 | PMBL | M, 23 | Cervical LN* | ++ |

| 11 | PMBL | F, 50 | Med | + |

| 12 | DLBCL | F, 33 | Axillary LN | − |

| 13 | DLBCL | M, 78 | Axillary LN | − |

| 14 | DLBCL | F, 49 | Inguinal LN | − |

| 15 | DLBCL | M, 54 | Cervical LN | − |

| 16 | DLBCL | M, 60 | Cervical LN | + |

| 17 | DLBCL | M, 55 | Cervical LN | − |

| 18 | DLBCL | M, 70 | Inguinal LN | − |

| 19 | DLBCL | F, 68 | Cervical LN | − |

| 20 | DLBCL | M, 61 | Inguinal LN | − |

| 21 | DLBCL | F, 68 | Axillary LN | − |

| 22 | cHL, NS | F, 20 | Cervical LN | +++ |

| 23 | cHL, NS | F, 22 | Cervical LN | +++ |

| 24 | cHL, NS | F, 26 | Cervical LN | +++ |

| 25 | cHL, NS | F, 40 | Cervical LN | +++ |

| 26 | cHL, NS | F, 24 | Cervical LN | − |

Case no. . | Diagnosis . | Sex and age, y . | Site . | P-STAT6 staining . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PMBL | F, 33 | Med | ++ |

| 2 | PMBL | F, 57 | Med | − |

| 3 | PMBL | F, 40 | Med | ++ |

| 4 | PMBL | M, 62 | Med | − |

| 5 | PMBL | F, 54 | Med | ++ |

| 6 | PMBL | M, 27 | Med | + |

| 7 | PMBL | M, 66 | Med | + |

| 8 | PMBL | F, 23 | Med | + |

| 9 | PMBL | F, 37 | Med | − |

| 10 | PMBL | M, 23 | Cervical LN* | ++ |

| 11 | PMBL | F, 50 | Med | + |

| 12 | DLBCL | F, 33 | Axillary LN | − |

| 13 | DLBCL | M, 78 | Axillary LN | − |

| 14 | DLBCL | F, 49 | Inguinal LN | − |

| 15 | DLBCL | M, 54 | Cervical LN | − |

| 16 | DLBCL | M, 60 | Cervical LN | + |

| 17 | DLBCL | M, 55 | Cervical LN | − |

| 18 | DLBCL | M, 70 | Inguinal LN | − |

| 19 | DLBCL | F, 68 | Cervical LN | − |

| 20 | DLBCL | M, 61 | Inguinal LN | − |

| 21 | DLBCL | F, 68 | Axillary LN | − |

| 22 | cHL, NS | F, 20 | Cervical LN | +++ |

| 23 | cHL, NS | F, 22 | Cervical LN | +++ |

| 24 | cHL, NS | F, 26 | Cervical LN | +++ |

| 25 | cHL, NS | F, 40 | Cervical LN | +++ |

| 26 | cHL, NS | F, 24 | Cervical LN | − |

PMBL indicates primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma; F, female; med, mediastinum; M, male; LN, lymph node; DLBCL, nonmediastinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; and cHL, NS, classical Hodgkin lymphoma, nodular sclerosis type. ++ indicates 25% to 50% positive tumoral cells; +, 10% to 20% positive tumoral cells; and −, less than 10% positive tumoral cells.

Patient with bulky mediastinal mass.

Altogether, these findings indicate that the transcription factor STAT6 is constitutively activated in PMBL-derived cell lines as well as in PMBL primary tumors, and that STAT6 phosphorylation represents a characteristic that distinguishes PMBL from DLBCL, but appears to be a common feature of both PMBL and cHL.

JAK2 gene amplification and overexpression in PMBL

STAT6 activation in PMBL might be due to JAK kinase activation. Comparative genomic hybridization and fluorescent interphase cytogenetic studies showed that approximately 50% to 70% of PMBL as well as the MedB1 cell line23 present chromosomal gains in the 9p region, comprising the locus encoding the JAK2 kinase, which participates in the IL-13 cellular response.14 We therefore performed Southern blot analysis in a limited number of PMBL and DLBCL cases using a JAK2 probe. The radioactivity bound to the 10-kb JAK2 genomic fragment and to the 5.5-kb β-globin genomic fragment was quantified with a phosphorimager. The JAK2/β-globin genomic ratio was 1.8 ± 0.2 in the majority of the PMBL (n = 4) and in all the DLBCL (n = 4) samples. There were 2 PMBL tumors that presented a higher JAK2/β-globin ratio (8 and 3; Figure 5A), indicating a 4- and 1.5-fold amplification, respectively, of the JAK2 gene in these samples. Gene amplification can result in increased expression. We performed quantitative RT-PCR analysis to analyze JAK2 mRNA expression in 22 PMBL and 20 DLBCL samples and derived cell lines. PMBL tumor samples presented significantly higher JAK2/S14 mRNA ratios (median = 56) than DLCBL (median = 35.5) (Figure 5B) (Mann-Whitney U test, P = .005). Of 22 samples, 6 presented noticeably higher JAK2 mRNA levels, suggesting a high degree of heterogeneity in JAK2 amplification/expression. STAT6-positive PMBL samples displayed medium to high JAK2 mRNA levels. The PMBL-derived cell lines MedB1 and Karpas 1106 presented substantially higher levels of JAK2 mRNA compared with the other DLCBL-derived cell lines (Figure 5C). It is interesting to note that the L428 HL cell line also showed high levels of JAK2 expression, a finding in agreement with the recent report of chromosome 9p24 amplification in cHL.24

JAK2 gene amplification and overexpression in PMBL. (A) Southern analysis of genomic DNA extracted from 6 PMBL (a-d) and 4 DLBCL (g-j) samples, digested with EcoRI, and hybridized simultaneously with a JAK2 and a β-globin probe. The radioactivity bound to the 10-kb JAK2 genomic fragment and to the 5.5-kb β-globin genomic fragment was quantified with a phosphorimager. JAK2/β-globin ratio was 1.8 ± 0.2 in samples c to j, 8 in sample a (arrow), and 3 in sample b (arrow). (B) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of JAK2 expression in 22 PMBL samples and 20 DLBCL samples. JAK2 mRNA levels, expressed as JAK2 mRNA copy number per 100 copies of S14 mRNA, were determined on frozen-tumor samples with no available formalin-fixed sections ( ), and in P-STAT6-positive (•) or P-STAT6-negative (○) tumors. Bars indicate median and interquartile values. (C) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of JAK2 expression, performed as in panel B, in 2 PMBL-derived cell lines (MedB1 and Karpas 1106) compared with 4 DLBCL-derived cell lines (SUDHL4, SUDHL6, OCI-Ly3, and OCI-Ly10), 1 Burkitt-derived cell line (Ramos), and 1 Hodgkin-derived cell line (L428).

), and in P-STAT6-positive (•) or P-STAT6-negative (○) tumors. Bars indicate median and interquartile values. (C) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of JAK2 expression, performed as in panel B, in 2 PMBL-derived cell lines (MedB1 and Karpas 1106) compared with 4 DLBCL-derived cell lines (SUDHL4, SUDHL6, OCI-Ly3, and OCI-Ly10), 1 Burkitt-derived cell line (Ramos), and 1 Hodgkin-derived cell line (L428).

JAK2 gene amplification and overexpression in PMBL. (A) Southern analysis of genomic DNA extracted from 6 PMBL (a-d) and 4 DLBCL (g-j) samples, digested with EcoRI, and hybridized simultaneously with a JAK2 and a β-globin probe. The radioactivity bound to the 10-kb JAK2 genomic fragment and to the 5.5-kb β-globin genomic fragment was quantified with a phosphorimager. JAK2/β-globin ratio was 1.8 ± 0.2 in samples c to j, 8 in sample a (arrow), and 3 in sample b (arrow). (B) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of JAK2 expression in 22 PMBL samples and 20 DLBCL samples. JAK2 mRNA levels, expressed as JAK2 mRNA copy number per 100 copies of S14 mRNA, were determined on frozen-tumor samples with no available formalin-fixed sections ( ), and in P-STAT6-positive (•) or P-STAT6-negative (○) tumors. Bars indicate median and interquartile values. (C) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of JAK2 expression, performed as in panel B, in 2 PMBL-derived cell lines (MedB1 and Karpas 1106) compared with 4 DLBCL-derived cell lines (SUDHL4, SUDHL6, OCI-Ly3, and OCI-Ly10), 1 Burkitt-derived cell line (Ramos), and 1 Hodgkin-derived cell line (L428).

), and in P-STAT6-positive (•) or P-STAT6-negative (○) tumors. Bars indicate median and interquartile values. (C) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of JAK2 expression, performed as in panel B, in 2 PMBL-derived cell lines (MedB1 and Karpas 1106) compared with 4 DLBCL-derived cell lines (SUDHL4, SUDHL6, OCI-Ly3, and OCI-Ly10), 1 Burkitt-derived cell line (Ramos), and 1 Hodgkin-derived cell line (L428).

JAK2 kinase activation in the MedB1 cell line

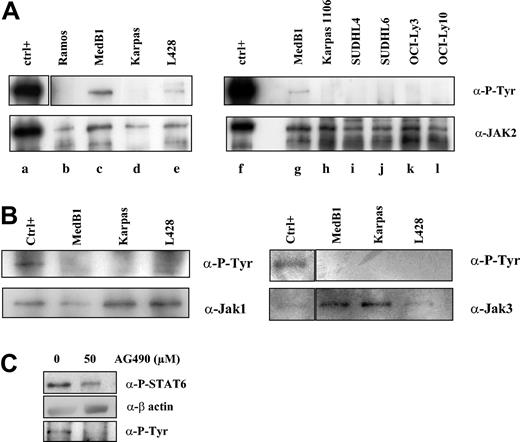

JAK kinases are activated by autophosphorylation or transphosphorylation of tyrosine in the activation loop. To determine whether these kinases are activated in PMBL, we performed immunoprecipitation experiments followed by immunoblotting with anti-P-tyrosine antibody on the PMBL- and other B lymphoma-derived cell lines (Figure 6A-B). We detected phosphorylation of the JAK2 protein in MedB1 and L428 lines, but not in Karpas 1106-, Ramos-, and DLBCL-derived cell lines (Figure 6A). We did not observe any JAK1 or JAK3 constitutive phosphorylation in PMBL-derived cell lines in immunoprecipitation experiments (Figure 6B) or in Western blot analysis using specific anti-phospho-JAK1/JAK3 antibodies (data not shown). These results suggest that the JAK2 kinase is constitutively activated in the PMBL-derived cell line MedB1.

Constitutive JAK2 activation in PMBL-derived MedB1 cells. (A) Whole-cell extracts from control (ctrl; TPO activated UT7-mpl, lanes a, f), 1 Burkitt-derived cell line (Ramos, lane b), 2 PMBL-derived cell lines (MedB1, lanes c, g; Karpas 1106, lanes d, h), 2 GC-DLBCL cell lines (SUDHL4, lane i; SUDHL6, lane j), and 2 ABC-DLBCL cell lines (OCI-Ly3, lane k; OCI-Ly10, lane l) were prepared and immunoprecipitated with anti-JAK2 antibodies. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blot using anti-P-Tyr or anti-JAK2 antibodies. (B) Whole-cell extracts from control (IL-4-treated MedB1 cells) and indicated cell lines were immunoprecipitated with anti-JAK1 or anti-JAK3 antibodies and were analyzed by Western blot using anti-P-Tyr or anti-JAK1 or JAK3 antibodies, as shown in the figure. (C) MedB1 cells were treated with DMSO or 50 μM AG490 for 24 hours. Whole cell extracts were analyzed by Western blot using anti-P-STAT6 or anti-β-actin antibodies as indicated on the right of the figure. The lower panel shows Western blot analysis of JAK2 immunoprecipitates with an anti-P-Tyr antibody.

Constitutive JAK2 activation in PMBL-derived MedB1 cells. (A) Whole-cell extracts from control (ctrl; TPO activated UT7-mpl, lanes a, f), 1 Burkitt-derived cell line (Ramos, lane b), 2 PMBL-derived cell lines (MedB1, lanes c, g; Karpas 1106, lanes d, h), 2 GC-DLBCL cell lines (SUDHL4, lane i; SUDHL6, lane j), and 2 ABC-DLBCL cell lines (OCI-Ly3, lane k; OCI-Ly10, lane l) were prepared and immunoprecipitated with anti-JAK2 antibodies. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blot using anti-P-Tyr or anti-JAK2 antibodies. (B) Whole-cell extracts from control (IL-4-treated MedB1 cells) and indicated cell lines were immunoprecipitated with anti-JAK1 or anti-JAK3 antibodies and were analyzed by Western blot using anti-P-Tyr or anti-JAK1 or JAK3 antibodies, as shown in the figure. (C) MedB1 cells were treated with DMSO or 50 μM AG490 for 24 hours. Whole cell extracts were analyzed by Western blot using anti-P-STAT6 or anti-β-actin antibodies as indicated on the right of the figure. The lower panel shows Western blot analysis of JAK2 immunoprecipitates with an anti-P-Tyr antibody.

In order to understand whether JAK2 activity is responsible for STAT6 activation in the MedB1 cell line, cells were treated with the JAK2 inhibitor, AG490 (Figure 6B). At 50 μM AG490, JAK2 phosphorylation was inhibited and STAT6 phosphorylation was partially reduced. This experiment suggests that JAK2 participates in STAT6 activation in this cell line.

Discussion

In the present work, we demonstrate that the signaling and transcription factor STAT6 is constitutively activated in PMBL-derived cell lines and primary tumors. This activation is independent of IL-4 and IL-13 stimulation, as these 2 cytokines are absent in PMBL-derived cell lines. We show also that STAT6 activation is a specific characteristic of PMBL that distinguishes it from DLBCL. Since there are currently no histologic features that can reliably distinguish PMBL from DLBCL, immunohistochemical detection of nuclear P-STAT6 could be used, in addition to MAL protein detection, to improve the histopathologic diagnosis of this peculiar lymphoma subtype.3,7

While distinctive in comparison to DLBCL, STAT6 activation is a common characteristic of PMBL and cHL. Actually, PMBL and cHL share some features, such as cytogenetic abnormalities (namely 9p and 2p gains), mediastinal involvement, and fibrotic reaction.23,24 The similarity of these 2 B-cell tumoral neoplasms has been recently emphasized by DNA microarray experiments showing a partially shared transcriptional signature5,6 that clearly reflects the activation of a common set of transcription factors, such as STAT6 and the nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) cREL factors.6 The transcriptional similarity between PMBL and cHL could be due to common oncogenic events, such as the specific chromosomal gains present in these 2 lymphomas. Alternatively, these similarities could also be due to the fact that these tumors originate from a similar B cell. In this respect, Marafioti et al recently characterized a population of large B cells, often with stellate morphology, in the T-cell-rich regions of peripheral lymphoid tissues.25 These cells resemble thymic B cells proposed as the normal counterpart of PMBL, and the authors suggested that these cells might give rise to B-cell lymphomas and pointed out several arguments suggesting a possible relationship with cHL. However, the mechanism responsible for STAT6 activation differs in PMBL and cHL. Indeed, it has been shown that autocrine IL-13 production by HRS cells is largely responsible for STAT6 activation and controls cell growth in HL-derived cell lines.19 On the contrary, we have not found significant IL-13 production in PMBL tumors and cell lines, with the exception of one peculiar case that contained a proportion of HRS-like cells.

Activation of STAT proteins, essentially STAT3 and STAT5, has been observed in several tumors and often in hematologic pathologies.26 The constitutive activation of these transcription factors is induced by various routes, including overexpression/deregulation of kinases or inhibition of negative regulators. Their role in cellular transformation has been linked to the transcriptional regulation of specific genes controlling cell viability, proliferation, and angiogenesis.27 To our knowledge, the constitutive activation of STAT6 has been previously reported only in cHL19 and prostate cancer.28 We hypothesized that STAT6 activation could be related to the oncogenic activation of a JAK kinase, and focused our attention on JAK2, which plays a critical role in several hematologic malignancies29 and the gene for which lies in a chromosomal region frequently affected in PMBL. We have shown here that the JAK2 gene is amplified in 2 of 6 cases of PMBL, and that JAK2 mRNA is overexpressed in a significant number of PMBL cases, in accordance with recent DNA microarray data.5,6 Moreover, we found that the JAK2 protein is constitutively phosphorylated in the MedB1 cell line, and is thereby most probably activated. Treatment of these cells with the JAK2 inhibitor Tyrphostin AG490 induced a partial decrease in STAT6 phosphorylation, suggesting that JAK2 might be partially responsible for STAT6 activation in this particular cell line. However, AG490 treatment did not totally inhibit STAT6 phosphorylation in these cells, phosphorylated JAK2 was not detected in the Karpas 1106 PMBL-derived cell line, and there was no clear correlation between JAK2 mRNA expression and STAT6 phosphorylation in PMBL and DLBCL samples. These observations suggest that STAT6 activation in PMBL could also be due to other events, as reported for STAT3 activation in anaplastic T/null-cell lymphoma.30,31 Other tyrosine kinases may participate in STAT6 phosphorylation, such as Src kinases.32 STAT6 constitutive activation may also be the consequence of a defect in the negative control of this signaling pathway, such as decreased dephosphorylation and/or decreased expression of the negative regulators of the JAK/STAT pathway of the suppressor of the cytokine signaling (SOCS) family. Studies of Oka et al33 have indeed shown that lymphomas generally express low levels of SH2 domain containing tyrosine phosphatase 1 (SHP1). Moreover, SHP1 was recently shown to participate in the rapid inactivation of STAT6 following cytokine stimulation,34 and promoter methylation was shown to decrease SOCS expression in several tumors.35,36

Transcriptional profiling of PMBL has revealed that this lymphoma subtype displays increased expression of IL-13Rα1, IL-13 signaling effectors (JAK2, STAT1), and IL-4/IL-13 targets (FIG1/IL-4I1, CD23, NF-IL3, TARC).4-6 In this respect, it is interesting that MAL, which we previously identified as a specific marker of PMBL, was recently shown to be highly up-regulated in T cells in response to IL-4 stimulation.37 The activation of the transcription factor primarily responsible for IL-4/IL-13-dependent gene regulation, STAT6, as shown here confirms the downstream activation of this cytokine pathway in PMBL. To decipher the role of STAT6 activation in PMBL physiopathology, it will be necessary to specifically interfere with STAT6 expression or function, using dominant-negative forms of STAT6 or STAT6 RNA interference. Efforts are currently under way to reach this objective. Given the fact that the activation of STAT6 is a common feature shared by 2 lymphomas with mediastinal localization, such as PMBL and cHL, we speculate that genes activated by this transcription factor could participate in the specific localization of these tumors.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, March 25, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3545.

Supported by the INSERM PROGRAMME AVENIR 2001 (F.C.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

The authors are indebted to L. Staudt for providing DLBCL-derived cell lines, G. Delsol for the cHL-derived L428 cell line, P. Moëller for the MedB1 cell line, and M. Dyer for the Karpas 1106 line. We gratefully acknowledge the following pathologists who provided pathologic material: J. Brière, M. Parrens, B. Petit, and A. C. Baglin. We thank François Berrehar and Amel Seïkour for help in quantitative RT-PCR. We also thank P. H. Romeo and W. M. Hempel for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was part of an INSERM PROGRAMME AVENIR to F.C.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal