Abstract

Promoter hypermethylation plays an important role in the inactivation of cancer-related genes. This abnormality occurs early in leukemogenesis and seems to be associated with poor prognosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). To determine the extent of hypermethylation in ALL, we analyzed the methylation status of the CDH1, p73, p16, p15, p57, NES-1, DKK-3, CDH13, p14, TMS-1, APAF-1, DAPK, PARKIN, LATS-1, and PTEN genes in 251 consecutive ALL patients. A total of 77.3% of samples had at least 1 gene methylated, whereas 35.9% of cases had 4 or more genes methylated. Clinical features and complete remission rate did not differ among patients without methylated genes, patients with 1 to 3 methylated genes (methylated group A), or patients with more than 3 methylated genes (methylated group B). Estimated disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) at 11 years were 75.5% and 66.1%, respectively, for the nonmethylated group; 37.2% and 45.5% for methylated group A; and 9.4% and 7.8% for methylated group B (P < .0001 and P = .0004, respectively). Multivariate analysis demonstrated that the methylation profile was an independent prognostic factor in predicting DFS (P < .0001) and OS (P = .003). Our results suggest that the methylation profile may be a potential new biomarker of risk prediction in ALL.

Introduction

Cytogenetic studies in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) reveal a wide variety of translocations involving this disease; these translocations can either (1) deregulate an intact gene by disruption or removal and replacement of the adjacent controlling elements or (2) create a new fusion gene.1,2 Chromosome translocation is clearly an important oncogenic step in ALL, and structurally altered genes play key roles in cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and gene transcription. Although these molecular abnormalities may serve as diagnostic and prognostic markers, they are detectable only at low rates in specific morphologic subtypes of ALL.1,2 Furthermore, oncogenes and tumor-suppressor genes that are frequently altered in solid tumors, such as p53 or RAS, are infrequently mutated in ALL.3 In addition to these genetic changes, epigenetic silencing of tumor-related genes, due to hypermethylation, has recently emerged as one of the pivotal alterations in cancer development.4-6

In the mammalian genome, methylation takes place only at cytosine bases that are located 5′ to guanosine in a CpG dinucleotide.4-6 This dinucleotide is actually underrepresented in much of the genome, but short regions of 0.5 to 4 kb in length, known as CpG islands, are rich in CpG content. Most CpG islands are found in the proximal promoter regions of almost half of the genes in the human genome and are, generally, unmethylated in normal cells. In cancer, however, the hypermethylation of these promoter areas is the most well-recognized epigenetic change to occur in tumors; it is found in virtually every type of neoplasm and is associated with the inappropriate transcriptional silencing of genes.4-6 Thus, aberrant methylation serves as an alternative mechanism of gene inactivation in neoplasia, and surprisingly, such promoter hypermethylation is at least as common as the disruption of classic tumor-suppressor genes in human cancer by mutation or deletion and possibly more common.

In addition, promoter hypermethylation and transcriptional repression of functionally important cancer-related genes may also affect tumor behavior, creating an impact on clinical outcomes. Epigenetic silencing of genes that determine tumor invasiveness, growth patterns, and apoptosis, in particular, may dictate tumor recurrence after treatment and affect overall survival. Because each tumor may harbor multiple genes susceptible to promoter hyper-methylation, individual tumors would exhibit different frequencies of hypermethylation profile potentially predictive of a patient's clinical outcome.7,8

Although several reports concerning methylation of different genes in ALL have been published, in most cases the methylation status has been investigated for just a single gene or in a small number of patients with short follow-up. We and others have identified several methylated genes in ALL, including CALCA, ER, MDR1, THBS2, MYF3, p15, p16, p73, p57, and CDH1.9-15 Moreover, methylation patterns may have clinical implications in ALL in that CALCA, p15, p57, and p21 methylation were found to be associated with dismal outcome.11-15 However, it is unclear whether methylation of these genes are prognostic because of their own regulating functions or because they reflect a distinct pathway of tumorigenesis in ALL, with distinct expression profiles of genes that could influence prognosis as a consequence of the simultaneous methylation of multiple loci. To study this issue further, we have examined multiple key cancer genes undergoing epigenetic inactivation in a large set of de novo ALLs with the aim of obtaining a map of this alteration in the disease and its possible correlation with clinical features and patient outcome.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patients

We studied 251 consecutive patients (151 male, 100 female) who received a diagnosis of de novo ALL between January 1990 and December 2002. The median age at diagnosis in the study population as a whole was 14 years (range, 0.5-82 years). Of these patients, 124 were children (median age, 5 years; range, 0.5-14 years), and 127 presented adult ALL (median age, 29 years; range, 15-82 years). Informed consent was obtained from the patient or the patient's guardians. Diagnosis was established according to standard morphologic, cytochemical, and immunophenotypic criteria. Patients were studied at the time of initial diagnosis; were risk-stratified according to the therapeutic protocol used, which was always based on recognized prognostic features (including cytogenetics); and were entered in ALL protocols of the Programa para el estudio y tratamiento de las hemopatias malignas (PETHEMA) Spanish study group. For statistical analyses, children were also grouped according to the National Cancer Institute (NCI) risk-classification criteria.16 The specific PETHEMAALL treatment protocols in which these patients were entered included ALL-89 (between 1990 and 1993; n = 51) and ALL-93 (between 1993 and 2002; n = 200). The design and results of these studies have been previously reported.17-20 Relapse occurred in 104 patients. Forty-four patients received stem cell transplants (14 autologous, 30 allogeneic) in the first (n = 20) or second (n = 24) complete remission (CR). There are 139 patients currently alive. Clinical characteristics of the patients are listed in Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and outcomes of 251 patients by methylation profile

Feature . | Nonmethylated group, n = 57, % . | Methylated group A, n = 104, % . | Methylated group B, n = 90, % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age* | |||

| Younger than 15 years | 61 | 46 | 45 |

| Older than 15 years | 39 | 54 | 55 |

| Sex, M/F | 56/44 | 60/40 | 63/37 |

| WBC count* | |||

| Lower than 50 × 109/L | 76 | 75 | 63 |

| Higher than 50 × 109/L | 24 | 25 | 37 |

| FAB classification | |||

| L1 | 38 | 40 | 25 |

| L2 | 50 | 56 | 64 |

| L3 | 12 | 4 | 11 |

| Blast lineage | |||

| B | 88 | 76 | 64 |

| T | 12 | 24 | 36 |

| NCI risk group | |||

| Standard | 80 | 76 | 65 |

| Poor | 20 | 24 | 35 |

| PETHEMA risk group | |||

| Standard | 40 | 47 | 34 |

| Poor | 60 | 53 | 66 |

| Treatment | |||

| PETHEMA 89 | 20 | 21 | 20 |

| PETHEMA 93 | 80 | 79 | 80 |

| BMT | 14 | 17 | 20 |

| Best response, CR | 91 | 93 | 88 |

| Cytogenetic/molecular abnormalities | |||

| BCR/ABL | 21 | 20 | 12 |

| 4(1;19) | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| 11q23 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| c-Myc | 6 | 3 | 8 |

| 7q35-14q11 | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| Hyperdiploidy | 9 | 6 | 5 |

| TEL-AML1 | 5 | 16 | 18 |

| None | 42 | 39 | 40 |

| Others | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| NT | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Relapse† | 17 | 51 | 59 |

| Death‡ | 28 | 43 | 61 |

Feature . | Nonmethylated group, n = 57, % . | Methylated group A, n = 104, % . | Methylated group B, n = 90, % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age* | |||

| Younger than 15 years | 61 | 46 | 45 |

| Older than 15 years | 39 | 54 | 55 |

| Sex, M/F | 56/44 | 60/40 | 63/37 |

| WBC count* | |||

| Lower than 50 × 109/L | 76 | 75 | 63 |

| Higher than 50 × 109/L | 24 | 25 | 37 |

| FAB classification | |||

| L1 | 38 | 40 | 25 |

| L2 | 50 | 56 | 64 |

| L3 | 12 | 4 | 11 |

| Blast lineage | |||

| B | 88 | 76 | 64 |

| T | 12 | 24 | 36 |

| NCI risk group | |||

| Standard | 80 | 76 | 65 |

| Poor | 20 | 24 | 35 |

| PETHEMA risk group | |||

| Standard | 40 | 47 | 34 |

| Poor | 60 | 53 | 66 |

| Treatment | |||

| PETHEMA 89 | 20 | 21 | 20 |

| PETHEMA 93 | 80 | 79 | 80 |

| BMT | 14 | 17 | 20 |

| Best response, CR | 91 | 93 | 88 |

| Cytogenetic/molecular abnormalities | |||

| BCR/ABL | 21 | 20 | 12 |

| 4(1;19) | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| 11q23 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| c-Myc | 6 | 3 | 8 |

| 7q35-14q11 | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| Hyperdiploidy | 9 | 6 | 5 |

| TEL-AML1 | 5 | 16 | 18 |

| None | 42 | 39 | 40 |

| Others | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| NT | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Relapse† | 17 | 51 | 59 |

| Death‡ | 28 | 43 | 61 |

Methylated group A indicates patients with 1, 2, or 3 methylated genes; methylated group B, patients with more than 3 methylated genes.

WBC indicates white blood cell; FAB, French-American-British; NCI, National Cancer Institute; PETHEMA, Programa para el estudio y tratamiento de las hemopatias malignas; BMT, bone marrow transplantation; CR, complete remission; and NT, not tested.

P = .09.

P < .0001.

P < .001.

Gene selection

High–molecular weight DNA and total RNA were prepared from mononuclear marrow cells at the time of diagnosis with the use of conventional methods. In all the cases, the diagnostic bone marrow sample contained at least 70% blast cells. We studied 15 genes belonging to all of the molecular pathways involved in cell immortalization and transformation: cell cycle (p15, p16, and p57); cell adherence and metastasis process (CDH1 and CDH13); p53 network (p14 and p73); apoptosis (TMS1, APAF-1, and DAPK); cellular senescence (DKK-3); differentiation regulation (NES-1); ubiquitylation (PARKIN); and main tumor-suppressor genes (LATS-1 and PTEN). Different criteria were used for gene selection. CDH1, p73, p16, p15, p57, NES-1, and DKK-3 were selected because of their frequent methylation in ALL.9-11,15,21,22 CDH13, p14, TMS1, APAF-1, DAPK, PARKIN, LATS-1, and PTEN were studied because they have been found to be methylated in other malignancies, and their abnormal expression could have potentially important roles in ALL23-30 (Table 2). The regions where these genes reside are not prone to mutations, deletions, or rearrangement in the majority of human leukemias; however, microsatellite markers from these regions have shown that most of them are common sites for loss of heterozygocity in ALL.31 Each of these genes possesses a CpG island in the 5′ region, which is normally unmethylated in corresponding normal tissues as expected for a typical CpG island. We and others have shown, in previous studies for such genes in individual tumor types, that when these CpG islands are hypermethylated in cancer cells, expression of the corresponding gene is silenced and the silencing can be partially relieved by demethylation of the promoter region.9-11,15,21-30 For all these genes, we have analyzed at least 10 normal marrow and peripheral blood specimens, none of which showed significant methylation.

Genes studied for methylation in ALL

Gene . | Location . | Function . | Reference for MSP primers . |

|---|---|---|---|

| NES-1 | 19q13 | Growth and differentiation control; putative TSG | Roman-Gomez et al21 |

| LATS-1 | 6q23-25 | TSG; G2-M cell cycle control; apoptosis regulation | Hisaoka et al29 |

| CDH1 | 16q22 | TSG; calcium-dependent cell-cell adhesion | Melki et al10 |

| CDH13 | 16q24 | Calcium-dependent cell-cell adhesion | Roman-Gomez et al23 |

| p16 | 9p21 | TSG; G1-S cell cycle control | Wong et al11 |

| APAF-1 | 12q23 | Apoptosis regulation | Fu et al26 |

| DKK-3 | 11p15 | Wnt/catenin signaling pathway antagonist; mortalization-related gene; putative TSG | Roman-Gomez et al22 |

| p15 | 9p21 | G1-S cell cycle control; putative TSG | Wong et al11 |

| PARKIN | 6q25-27 | E3 ubiquitin ligase; putative TSG | Cesari et al28 |

| PTEN | 10q23 | TSG; cell adhesion/motility; apoptosis; angiogenesis; G1 cell cycle regulation; signal transduction | Zysman et al30 |

| p57 | 11p15 | G1-S cell cycle control; putative TSG | Shen et al15 |

| p73 | 1p36 | G1-S cell cycle control; putative TSG | Kawano et al9 |

| DAPK | 9q34 | Apoptosis regulation | Katzenellenbogen et al27 |

| TMS-1 | 16p11-12 | Apoptosis regulation | Conway et al25 |

| p14 | 9p21 | Cell cycle control; apoptosis regulation | Esteller et al24 |

Gene . | Location . | Function . | Reference for MSP primers . |

|---|---|---|---|

| NES-1 | 19q13 | Growth and differentiation control; putative TSG | Roman-Gomez et al21 |

| LATS-1 | 6q23-25 | TSG; G2-M cell cycle control; apoptosis regulation | Hisaoka et al29 |

| CDH1 | 16q22 | TSG; calcium-dependent cell-cell adhesion | Melki et al10 |

| CDH13 | 16q24 | Calcium-dependent cell-cell adhesion | Roman-Gomez et al23 |

| p16 | 9p21 | TSG; G1-S cell cycle control | Wong et al11 |

| APAF-1 | 12q23 | Apoptosis regulation | Fu et al26 |

| DKK-3 | 11p15 | Wnt/catenin signaling pathway antagonist; mortalization-related gene; putative TSG | Roman-Gomez et al22 |

| p15 | 9p21 | G1-S cell cycle control; putative TSG | Wong et al11 |

| PARKIN | 6q25-27 | E3 ubiquitin ligase; putative TSG | Cesari et al28 |

| PTEN | 10q23 | TSG; cell adhesion/motility; apoptosis; angiogenesis; G1 cell cycle regulation; signal transduction | Zysman et al30 |

| p57 | 11p15 | G1-S cell cycle control; putative TSG | Shen et al15 |

| p73 | 1p36 | G1-S cell cycle control; putative TSG | Kawano et al9 |

| DAPK | 9q34 | Apoptosis regulation | Katzenellenbogen et al27 |

| TMS-1 | 16p11-12 | Apoptosis regulation | Conway et al25 |

| p14 | 9p21 | Cell cycle control; apoptosis regulation | Esteller et al24 |

MSP indicates methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction; TSG, tumor suppressor gene; E3, early region 3.

Methylation-specific PCR (MSP)

Aberrant promoter methylation of these genes was determined by the MSP method as reported by Herman et al.32 MSP distinguishes unmethylated alleles of a given gene on the basis of DNA sequence alterations after bisulfite treatment of DNA, which converts unmethylated, but not methylated, cytosines to uracils. Subsequent polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers specific to sequences corresponding to either methylated or unmethylated DNA sequences was then performed. Primer sequences of each gene for the unmethylated and methylated reactions have been reported elsewhere.9-11,15,21-30 “Hot-start” PCR was performed for 30 cycles; this consists of denaturation at 95° C for 1 minute, annealing at 60° C for 1 minute, and extension at 72° C for 1 minute, followed by a final 7-minute extension for all primer sets. The products were separated by electrophoresis on 2% agarose gel. Bone marrow DNA from healthy donors was used as negative control for methylation-specific assays. Human male genomic DNA universally methylated for all genes (Intergen, Purchase, NY) was used as a positive control for methylated alleles. Water blanks were included with each assay. The presence of a clearly visible band in the MSP using primers for the methylated alleles was considered a positive result for methylation. This result was always confirmed by repeat MSP assays after an independently performed bisulfite treatment. In the sporadic cases where only faint bands were observed in both analyses, methylation results were validated by Southern blot, sequencing, and/or association with lack of expression assessed by reverse-transcription PCR (RT-PCR) as appropriate. The sensitivity of this MSP was established by using totally methylated, positive control DNA serially diluted by normal lymphocyte DNA. MSPs with positive control DNA diluted in ratios of 1:10, 1:100, and 1:1000 produced detectable methylated bands (data not shown).

Other molecular analyses

Standard Southern blot method was employed to detect immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene rearrangement and T-cell receptor–β rearrangement. The 11q23 abnormalities were studied with the B859 probe kindly provided by Dr G. Cimino (Rome, Italy).33 The p210BCR-ABL, p190BCR-ABL, and TEL-AML1 fusion transcripts were detected by means of the reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction according to the primers and protocols established by the European BIOMED 1 concerted action.34

Statistical analysis

For statistical purposes, ALL patients were classified into 2 different methylation groups: nonmethylated (no methylated genes) and methylated (at least one methylated gene). The methylated group was also divided into 2 other groups according to the number of methylated genes observed in each individual sample: methylated group A (1 to 3 methylated genes) and methylated group B (more than 3 methylated genes). P values for comparisons of continuous variables in groups of patients were 2-tailed and were based on the Wilcoxon rank sum test. P values for dichotomous variables were based on the Fisher exact test. The remaining P values were based on the Pearson chi-square test. Overall survival (OS) was measured from the day of diagnosis until death from any cause and was censored only for patients known to be alive at last contact. Disease-free survival (DFS) was measured from the day that CR was established until either relapse or death without relapse, and it was censored only for patients who were alive without evidence of relapse at the last follow-up. Distributions of OS and DFS curves were estimated by the method of Kaplan and Meier, with 95% confidence intervals calculated by means of Greenwood's formula. Comparisons of groups by OS or DFS were based on the log-rank test. Comparisons adjusted for significant prognostic factors were based on Cox regression models and hazard regression models. All relapse and survival data were updated on December 2003, and all follow-up data were censored at that point.

Results

Frequency of methylation in ALL

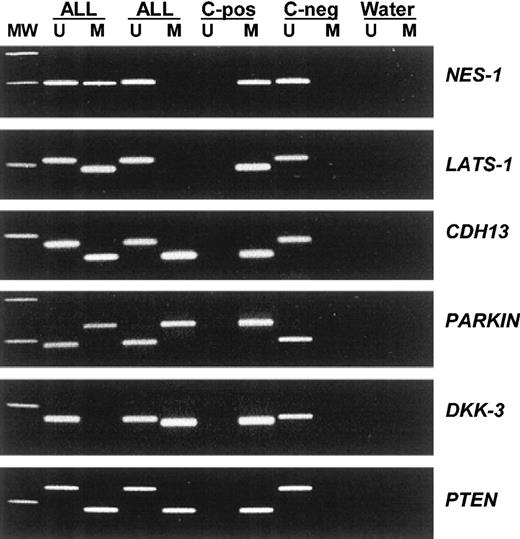

Among 251 ALLs, the methylation frequencies (in descending order) were as follows: 57% for NES-1, 40% for LATS-1, 37% for CDH1, 35% for CDH13, 35% for p16, 34% for APAF-1, 33% for DKK-3, 29% for p15, 27% for PARKIN, 20% for PTEN, 18% for p57, 18% for p73, 13% for DAPK, 9% for TMS-1, and 8.5% for p14 (Table 3). No methylated genes were found in 57 (22.7%) of 251 patients, whereas most ALLs (194 [77.3%] of 251) had methylation of at least 1 methylated gene (range, 1-10) (Table 3). No case was found to have methylation of more than 10 genes. According to the number of methylated genes observed in each individual sample, 104 patients (41.4%) were included in methylated group A (1 to 3 methylated genes) and 90 (35.9%) in methylated group B (more than 3 methylated genes). Significant differences were found between methylation profiles in children and adults. LATS-1 (P = .05), CDH1 (P = .05), p15 (P = .05), p57 (P = .001), and p14 (P = .05) genes were more frequently methylated in adult ALL than in childhood ALL (Table 3). Moreover, 82.7% of adult ALLs showed methylated genes compared with 71.8% of childhood ALLs (P = .03) (Table 3). Figure 1 illustrates representative examples of the methylation patterns of the most frequently methylated genes.

Methylation profile in ALL

Feature . | Overall, % . | Childhood ALL, % . | Adult ALL, % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methylated genes | |||

| NES-1 | 57 | 55 | 58 |

| LATS-1* | 40 | 30 | 47 |

| CDH1* | 37 | 32 | 42 |

| CDH13 | 35 | 32 | 37 |

| p16 | 35 | 32 | 36 |

| APAF-1 | 34 | 35 | 34 |

| DKK-3 | 33 | 32 | 33 |

| p15* | 29 | 20 | 38 |

| PARKIN | 27 | 30 | 24 |

| PTEN | 20 | 20 | 19 |

| p57† | 18 | 2 | 34 |

| p73 | 18 | 18 | 18 |

| DAPK | 13 | 10 | 17 |

| TMS-1 | 9 | 10 | 7 |

| p14* | 8.5 | 5 | 13 |

| Methylation group | |||

| Nonmethylated‡ | 22.7 | 28.2 | 17.3 |

| Methylated | 77.3 | 71.8 | 82.7 |

| Group A | 41.4 | 38.7 | 44.1 |

| Group B | 35.9 | 33.1 | 38.6 |

| No. methylated genes | |||

| 0* | 22.7 | 28.2 | 18.1 |

| 1 | 9.3 | 8.1 | 9.4 |

| 2 | 19.9 | 21 | 18.9 |

| 3 | 12.7 | 9.7 | 15.7 |

| 4 | 10 | 6.5 | 13.4 |

| 5 | 10 | 9.7 | 10.2 |

| 6 | 5.6 | 6.5 | 4.7 |

| 7 | 4.8 | 6.5 | 3.1 |

| 8 | 2 | 1.6 | 2.4 |

| 9 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| 10 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 2.4 |

Feature . | Overall, % . | Childhood ALL, % . | Adult ALL, % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methylated genes | |||

| NES-1 | 57 | 55 | 58 |

| LATS-1* | 40 | 30 | 47 |

| CDH1* | 37 | 32 | 42 |

| CDH13 | 35 | 32 | 37 |

| p16 | 35 | 32 | 36 |

| APAF-1 | 34 | 35 | 34 |

| DKK-3 | 33 | 32 | 33 |

| p15* | 29 | 20 | 38 |

| PARKIN | 27 | 30 | 24 |

| PTEN | 20 | 20 | 19 |

| p57† | 18 | 2 | 34 |

| p73 | 18 | 18 | 18 |

| DAPK | 13 | 10 | 17 |

| TMS-1 | 9 | 10 | 7 |

| p14* | 8.5 | 5 | 13 |

| Methylation group | |||

| Nonmethylated‡ | 22.7 | 28.2 | 17.3 |

| Methylated | 77.3 | 71.8 | 82.7 |

| Group A | 41.4 | 38.7 | 44.1 |

| Group B | 35.9 | 33.1 | 38.6 |

| No. methylated genes | |||

| 0* | 22.7 | 28.2 | 18.1 |

| 1 | 9.3 | 8.1 | 9.4 |

| 2 | 19.9 | 21 | 18.9 |

| 3 | 12.7 | 9.7 | 15.7 |

| 4 | 10 | 6.5 | 13.4 |

| 5 | 10 | 9.7 | 10.2 |

| 6 | 5.6 | 6.5 | 4.7 |

| 7 | 4.8 | 6.5 | 3.1 |

| 8 | 2 | 1.6 | 2.4 |

| 9 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| 10 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 2.4 |

P = .05.

P = .001.

P = .03.

Aberrant promoter methylation of different genes in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. MW indicates molecular weight marker; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia samples; C-pos, human male genomic DNA universally methylated for all genes (used as a positive control for methylated alleles); C-neg, healthy individual; water, blank control without DNA added; U, unmethylated alleles; and M, methylated alleles.

Aberrant promoter methylation of different genes in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. MW indicates molecular weight marker; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia samples; C-pos, human male genomic DNA universally methylated for all genes (used as a positive control for methylated alleles); C-neg, healthy individual; water, blank control without DNA added; U, unmethylated alleles; and M, methylated alleles.

By analyzing the methylation status of 15 genes simultaneously, we were able to study correlations between their methylation status. Methylation of DKK-3, NES-1, PARKIN, LATS-1, PTEN, p73, p16, p14, CDH1, CDH13, DAPK, and p15 genes were significantly correlated (Table 4). By contrast, methylation of TMS1 and p57 showed no significant correlation with each other or with any of the gene groups mentioned in this paragraph.

Correlations between methylation status of the different genes studied

. | NES . | DKK . | PARKIN . | APAF . | LATS . | PTEN . | p57 . | p73 . | p16 . | p14 . | CDH1 . | CDH13 . | DAPK . | TMS . | p15 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NES | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| DKK | .0001 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| PARKIN | .0001 | .0001 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| APAF | NS | NS | NS | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| LATS | .006 | NS | NS | .0001 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| PTEN | .0001 | .0001 | .0001 | NS | NS | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| p57 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| p73 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | .001 | NS | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| p16 | .001 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | .0001 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| p14 | NS | .005 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CDH1 | .0001 | .0001 | .0001 | NS | NS | .0001 | NS | NS | NS | NS | — | — | — | — | — |

| CDH13 | .0001 | .0001 | .0001 | NS | .001 | .0001 | NS | NS | NS | .0001 | .0001 | — | — | — | — |

| DAPK | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | .0001 | .0001 | — | — | — |

| TMS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | — | — |

| p15 | .003 | .0001 | .0001 | NS | NS | .002 | .002 | .004 | .001 | NS | .0001 | .0001 | NS | NS | — |

. | NES . | DKK . | PARKIN . | APAF . | LATS . | PTEN . | p57 . | p73 . | p16 . | p14 . | CDH1 . | CDH13 . | DAPK . | TMS . | p15 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NES | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| DKK | .0001 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| PARKIN | .0001 | .0001 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| APAF | NS | NS | NS | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| LATS | .006 | NS | NS | .0001 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| PTEN | .0001 | .0001 | .0001 | NS | NS | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| p57 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| p73 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | .001 | NS | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| p16 | .001 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | .0001 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| p14 | NS | .005 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CDH1 | .0001 | .0001 | .0001 | NS | NS | .0001 | NS | NS | NS | NS | — | — | — | — | — |

| CDH13 | .0001 | .0001 | .0001 | NS | .001 | .0001 | NS | NS | NS | .0001 | .0001 | — | — | — | — |

| DAPK | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | .0001 | .0001 | — | — | — |

| TMS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | — | — |

| p15 | .003 | .0001 | .0001 | NS | NS | .002 | .002 | .004 | .001 | NS | .0001 | .0001 | NS | NS | — |

— indicates already performed; and NS, nonsignificant.

Clinical outcome and methylation profile

As shown in Table 1, clinical and laboratory characteristics did not differ significantly between methylation groups. Poor-risk cytogenetics or molecular events, risk groups according to both NCI and PETHEMA classifications, good risk features (hyperdiploidy and TEL-AML1 fusion), type of PETHEMA protocol administered, and number of patients who received stem cell transplants were distributed similarly among the 3 methylation groups. Separate analysis of adult and childhood ALL patients gave the same results as the global series.

Table 1 details the relapse history, CR rates, and mortality for patients in the different methylation groups. CR rates of patients in the nonmethylated, methylated A, and methylated B groups were 91%, 93%, and 88%, respectively, accounting for 91% of the overall CR rate. This suggests that the methylation profile did not correlate with response to remission induction therapy. However, patients in the nonmethylated group had a lower rate of relapse than patients in methylated groups A and B (17% versus 51% and 59%, respectively, P < .0001). Mortality rate was also lower for the nonmethylated group compared with methylated groups A and B (28% versus 43% and 61%, respectively, P < .001). Similar results were obtained in the separate analyses of children (relapse rate, 14% for nonmethylated group versus 35% and 48% for methylated groups A and B, respectively, P = .003; mortality rate, 14% for nonmethylated group versus 20% and 37% for methylated groups A and B, respectively, P = .04) and adults (relapse rate, 28% for nonmethylated group versus 67% and 68% for methylated groups A and B, respectively, P = .002; mortality rate, 50% for nonmethylated group versus 63% and 81% for methylated groups A and B, respectively, P = .02).

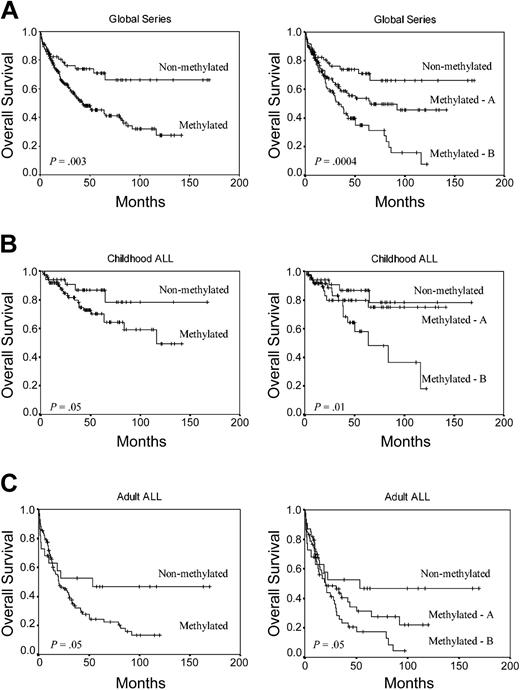

We analyzed the DFS among patients who achieved CR according to the methylation profile. Estimated DFS rates at 11 years were 75.5% and 25.6% for nonmethylated and methylated groups, respectively (group A, 37.2%; group B, 9.4%) (P < .0001) (Figure 2A). Among children, the 11-year DFS was 79.7% for nonmethylated group and 36.5% for methylated group (group A, 55%; group B, 18.6%; P = .001) (Figure 2B). Among adult ALL patients, the 11-year DFS was 66.5% for nonmethylated group and 15.6% for methylated group (group A, 20.4%; group B, 7.1%; P = .001) (Figure 2C). The actuarial OS at 12 years calculated for all leukemic patients was 66.1% for nonmethylated patients and 27.4% for methylated patients (group A, 45.5%; group B, 7.8%; P = .0004) (Figure 3A). Significant differences were observed in the actuarial OS among nonmethylated, methylated A, and methylated B groups in the separate analyses of children (78.1%, 75.1%, and 18.1%, respectively, P = .01) (Figure 3B) and adults (46.6%, 22.1% and 4.2%, respectively, P = .05) (Figure 3C).

Kaplan-Meier survivor function for ALL patients. DFS curves according to the methylation profile. Methylated group A indicates patients with 1 to 3 methylated genes; and methylated group B, patients with more than 3 methylated genes. (A) All patients enrolled in this study. (B) Childhood ALL. (C) Adult ALL.

Kaplan-Meier survivor function for ALL patients. DFS curves according to the methylation profile. Methylated group A indicates patients with 1 to 3 methylated genes; and methylated group B, patients with more than 3 methylated genes. (A) All patients enrolled in this study. (B) Childhood ALL. (C) Adult ALL.

Kaplan-Meier survivor function for ALL patients. OS curves according to the methylation profile. Methylated A indicates patients with 1 to 3 methylated genes; and methylated B, patients with more than 3 methylated genes. (A) All patients enrolled in this study. (B) Childhood ALL. (C) Adult ALL.

Kaplan-Meier survivor function for ALL patients. OS curves according to the methylation profile. Methylated A indicates patients with 1 to 3 methylated genes; and methylated B, patients with more than 3 methylated genes. (A) All patients enrolled in this study. (B) Childhood ALL. (C) Adult ALL.

A multivariate analysis of potential prognostic factors (including the type of PETHEMA protocol applied) demonstrated that hypermethylation profile was an independent prognostic factor in predicting DFS in the global series (P < .0001) as well as in both childhood (P = .0001) and adult ALLs (P = .006) (Table 5). Methylation status was also independently associated with OS in the global series (P = .003) and childhood ALL (P = .02) (Table 6).

Multivariate Cox model for disease-free survival

Feature . | Univariate analysis P . | Multivariate analysis P . |

|---|---|---|

| Global series | ||

| Methylation profile | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| WBC count higher than 50 × 109/L | .0002 | .002 |

| BCR-ABL positivity | .004 | .01 |

| T phenotype | .03 | — |

| Age older than 15 years | .007 | — |

| PETHEMA poor risk | .04 | — |

| Childhood ALL | ||

| Methylation profile | .0001 | .0001 |

| PETHEMA poor risk | .05 | .05 |

| WBC count higher than 50 × 109/L | .05 | — |

| NCl poor risk | .05 | — |

| Adult ALL | ||

| BCR-ABL positivity | <.0001 | .001 |

| Methylation profile | .003 | .006 |

| WBC higher than 50 × 109/L | .0002 | .02 |

Feature . | Univariate analysis P . | Multivariate analysis P . |

|---|---|---|

| Global series | ||

| Methylation profile | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| WBC count higher than 50 × 109/L | .0002 | .002 |

| BCR-ABL positivity | .004 | .01 |

| T phenotype | .03 | — |

| Age older than 15 years | .007 | — |

| PETHEMA poor risk | .04 | — |

| Childhood ALL | ||

| Methylation profile | .0001 | .0001 |

| PETHEMA poor risk | .05 | .05 |

| WBC count higher than 50 × 109/L | .05 | — |

| NCl poor risk | .05 | — |

| Adult ALL | ||

| BCR-ABL positivity | <.0001 | .001 |

| Methylation profile | .003 | .006 |

| WBC higher than 50 × 109/L | .0002 | .02 |

— indicates not significant.

Multivariate Cox model for overall survival

Feature . | Univariate analysis P . | Multivariate analysis P . |

|---|---|---|

| Global series | ||

| WBC count higher than 50 × 109/L | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Methylation profile | .0005 | .003 |

| PETHEMA poor risk | <.0001 | .01 |

| Age older than 15 years | <.0001 | .05 |

| BCR-ABL positivity | .0003 | — |

| T phenotype | .005 | — |

| Childhood ALL | ||

| T phenotype | .005 | .005 |

| Methylation profile | .03 | .02 |

| WBC count higher than 50 × 109/L | .05 | — |

| NCl poor risk | .05 | — |

| Adult ALL | ||

| WBC count higher than 50 × 109/L | .0001 | .0001 |

| BCR-ABL positivity | .001 | .05 |

| Methylation profile | .03 | — |

Feature . | Univariate analysis P . | Multivariate analysis P . |

|---|---|---|

| Global series | ||

| WBC count higher than 50 × 109/L | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Methylation profile | .0005 | .003 |

| PETHEMA poor risk | <.0001 | .01 |

| Age older than 15 years | <.0001 | .05 |

| BCR-ABL positivity | .0003 | — |

| T phenotype | .005 | — |

| Childhood ALL | ||

| T phenotype | .005 | .005 |

| Methylation profile | .03 | .02 |

| WBC count higher than 50 × 109/L | .05 | — |

| NCl poor risk | .05 | — |

| Adult ALL | ||

| WBC count higher than 50 × 109/L | .0001 | .0001 |

| BCR-ABL positivity | .001 | .05 |

| Methylation profile | .03 | — |

See Table 5 footnote for abbreviations.

Prognostic impact of the methylation profile in selected risk groups

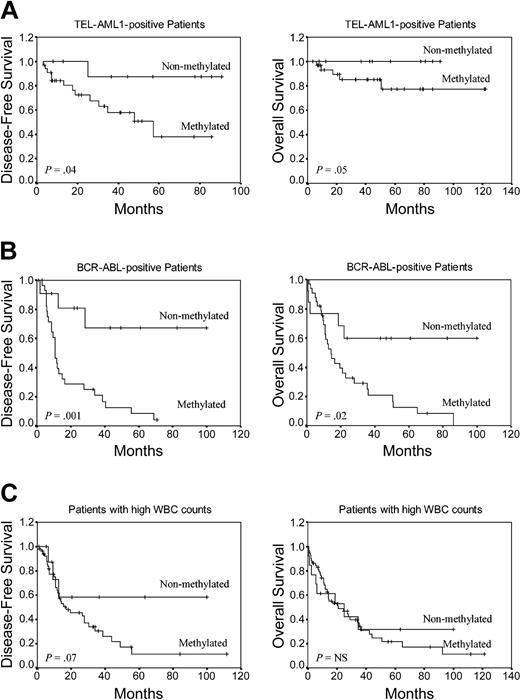

To determine the prognostic impact of the methylation profile in selected ALL groups with well-established prognostic factors, we analyzed DFS and OS in TEL-AML1+ and BCR-ABL+ patients and also in patients with high white blood cell (WBC) count (> 50 × 109/L [> 50 000 mm3]) at diagnosis. Among TEL-AML1+ children (n = 44), the 8-year DFS was 87.5% for the nonmethylated group and 38% for the methylated group (P = .04) (Figure 4A). The actuarial OS at 8 years for the same patients was 100% for nonmethylated patients and 77.4% for methylated patients (P = .05) (Figure 4A). Among BCR-ABL+ patients (n = 47), the 6-year DFS was 67.3% for nonmethylated patients and 4.1% for methylated patients (P = .001) (Figure 4B). Estimated 7-year OS was 59.8% for nonmethylated BCR-ABL patients and 0% for methylated patients (P = .02) (Figure 4B). Among ALL patients with high WBC count at diagnosis (n = 73), DFS at 9 years was 58.3% for nonmethylated patients and 11.5% for methylated patients (P = .07) (Figure 4C). No significant difference was observed in OS in these patients.

Kaplan-Meier survivor function for selected prognostic groups of ALL patients. DFS and OS curves according to the methylation profile. (A) TEL-AML1+ ALL patients. (B) BCR-ABL+ ALL patients. (C) Patients with high WBC count at diagnosis.

Kaplan-Meier survivor function for selected prognostic groups of ALL patients. DFS and OS curves according to the methylation profile. (A) TEL-AML1+ ALL patients. (B) BCR-ABL+ ALL patients. (C) Patients with high WBC count at diagnosis.

Discussion

Epigenetic gene silencing is increasingly being recognized as a common way in which cancer cells inactivate cancer-related genes.4-8 Attention has focused on the methylation of regions in the genome that might have functional significance resulting from the extinction of gene activity. Whereas most individual cancers have several, perhaps hundreds, of methylated genes (a phenomenon termed CpG island methylator phenotype),35 the methylation profiles of individual tumor types are characteristic of this type of cancer. However, there is relatively modest information on this profiling in ALL.13-15 Our results indicate that methylation of multiple genes is a common phenomenon in ALL and may be the most important way to inactivate cancer-related genes in this disease; 77.3% of cases had at least 1 gene methylated, whereas 35.9% of cases had 4 or more genes methylated. Significant differences were found in the methylation profiles of childhood and adult ALLs, suggesting that methylation status in ALL is age related. Adult ALL patients showed more frequent methylation of LATS-1, CDH1, p15, p57, and p14 genes and also a higher number of simultaneously methylated genes than childhood ALL patients. It is well known that prognosis of children with ALL is significantly superior to that of adults, even if they are matched for poor prognosis features; our results suggest that this different epigenetic map may have a role in explaining the prognostic differences in the 2 age groups. Furthermore, methylation of several of the genes analyzed here was strongly correlated, suggesting that CpG island methylation is related to specific methylation defects in subsets of ALLs, rather than that methylation of each individual island represents a random event followed by selection for the affected cell.

Our data also show that the methylation in human ALL cells can participate in the inactivation of 3 key cellular pathways:

growth-deregulating events comprising events that target the principal late-G1 cell cycle checkpoint either directly (p15, p16, and p57 inactivation) or indirectly (p73, PTEN, and NES-1 inactivation) and events that regulate the G2-M transition down-regulating CDC2/cyclin A kinase activity (LATS-1) and those that antagonize the WNT/beta-catenin oncogenic signaling pathway (DKK-3);

the apoptotic program through inactivation of p14, TMS1, APAF-1, and DAPK; and

the cell-cell adhesion by the inactivation of some members of the cadherin family (CDH13 and CDH1), which are more than simply a “sticky molecular complex” because they have the ability to inhibit cell proliferation by the up-regulation of p27 (another G1 checkpoint gene) and because their down-regulation also interferes with apoptotic signals putting the affected cell into a state of de facto anoikis.36

All these abnormalities are not surprising. Beneath the complexity and idiopathy of every cancer lies a limited number of “mission-critical” events that have propelled the tumor cell and its progeny into uncontrolled expansion and invasion. One of these is deregulated cell proliferation, which, together with the compensatory suppression of apoptosis needed to support it, provides a minimal “platform” necessary to support further neoplastic progression.37 Our data show that in ALL this common platform can be achieved by a methylation mechanism. Interestingly, although genetic abnormalities of key tumor-suppressor genes such as RB and, especially, p53 are the most common molecular lesions in human cancer,38 they are relatively less frequent in de novo ALL.3 In view of our results, one hypothesis is that the methylation of cytosine nucleotides in ALL cells can help inactivate (1) tumor-suppressive apoptotic or growth-arresting responses by deregulation of the cyclin-dependent kinases that phosphorylate and functionally inactive retinoblastoma (RB) protein (at the p15, p16, and p57 level) and either upstream (at p14 or DAPK) or downstream (APAF-1) of p53 and also (2) p73, which encodes for a protein that is both structurally and functionally homologous to the p53 protein.39 This implies that in ALL too there is a strong selection for tumor cells to lose critical tumor-suppressor gene functions (not only p53 and RB but also LATS-1 and PTEN) but, in this case, indirectly through an alternative epigenetic way.

In this study, we have shown that aberrant methylation of CpG islands is quantitatively different in individual tumors within the same tumor type and that this patient-specific methylation profile provides important prognostic information in ALL patients. The presence in individual tumors of multiple epigenetic events that affect each of the pathways we have discussed is a factor of poor prognosis in both childhood and adult ALL. Patients with methylation of 4 or more genes had a poorer DFS and OS than patients with 3 or fewer methylated genes or patients lacking promoter hypermethylation. Multivariate analysis confirmed that methylation profile was associated with a shorter DFS and OS. Moreover, methylation status was able to redefine the prognosis of selected ALL groups with well-established prognostic features. Lack of promoter methylation improved the generally poor outcome of patients presenting Philadelphia chromosome or high WBC count at diagnosis, whereas the presence of methylation worsened the generally good outcome of TEL-AML1+ patients. Therefore, methylation profiling in ALL could have important clinical implications, complementing standard immunophenotypic, cytogenetic, and molecular studies for guiding the selection of therapy and also providing a basis for developing novel therapies, such as demethylation treatment.

In summary, our results indicate that simultaneously aberrant methylation affecting key molecular pathways is a common phenomenon in ALL. The methylation profile seems to be an important factor in predicting the clinical outcome of ALL patients.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, June 15, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0954.

Supported by grants from Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (FIS; Spain) (PI030141, 01/0013-01, 01/F018, and 02/1299); Navarra goverment (31/2002); RETIC (C03/10); Junta de Andalucia (03/143; 03/144); and funds from Cajamar-Fundacion Hospital Carlos Haya (Malaga, Spain).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal