Abstract

Core binding factor (CBF) participates in specification of the hematopoietic stem cell and functions as a critical regulator of hematopoiesis. Translocation or point mutation of acute myeloid leukemia 1 (AML1)/RUNX1, which encodes the DNA-binding subunit of CBF, plays a central role in the pathogenesis of acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplasia. We characterized the t(X;21)(p22.3;q22.1) in a patient with myelodysplasia that fuses AML1 in-frame to the novel partner gene FOG2/ZFPM2. The reciprocal gene fusions AML1-FOG2 and FOG2-AML1 are both expressed. AML1-FOG2, which fuses the DNA-binding domain of AML1 to most of FOG2, represses the transcriptional activity of both CBF and GATA1. AML1-FOG2 retains a motif that recruits the corepressor C-terminal binding protein (CtBP) and these proteins associate in a protein complex. These results suggest a central role for CtBP in AML1-FOG2 transcriptional repression and implicate coordinated disruption of the AML1 and GATAdevelopmental programs in the pathogenesis of myelodysplasia.

Introduction

Myelodysplasia arises from genetic alterations in the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) that impair differentiation and lead to acute myeloid leukemia (AML).1 Differentiation of the HSC reflects restrictions in cell fate determined by transcription factors that function as master regulators of hematopoiesis.2 Thus, many genetic lesions in myelodysplasia affect transcription factors. Core binding factor (CBF) is a heterodimeric transcription factor, composed of a DNA-binding subunit AML1 (CBFα2/PEBP2αB/RUNX1)3 and its partner CBFβ,4 which participates in specification of the HSC.5-7 Genetic alterations involving the AML1 gene include translocations and point mutations, which represent critical events in the development of both myelodysplasia and AML.8 We hypothesized that chromosomal aberrations involving AML1 might identify other developmental programs that cooperate in the pathogenesis of myelodysplasia.

Study design

Fluorescence in-situ hybridization

Fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) was performed as described9,10 with paints for chromosomes X (Vysis, Downer's Grove, IL) and 21 (Cambio, Cambridge, England). Involvement of AML1 was verified by FISH with the TEL/AML1 probe (Vysis). Translocation of the 3′ end of FOG2 to the X chromosome was confirmed by FISH with the X chromosome centromere probe (Vysis) and bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) RP11-152P17 (Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute, Oakland, CA). Approval was obtained from the Indiana University institutional review board for these studies, and informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Rapid amplification of cDNA ends

Bone marrow RNA was used to prepare cDNA using primer QT (5′-ccagtgagcagagtgacgaggactcgagctcaagct18) with the Superscript First-strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). We performed 3′–rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) using nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers and the Advantage 2 PCR Kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). The first amplification included primers F4 (5′-ccacctaccacagagccatcaaaa) and Q1 (5′-ccagtgagcagagtgacgagg) with cycling: 95°C for 1 minute (1 time); 95°C for 30 seconds, 56°C for 30 seconds, 68°C for 3 minutes (35 times); 68°C for 3 minutes (1 time). The second amplification included primers G4 (5′-atcaaaatcacagtggatggg) and Q2 (5′-gacgaggactcgagctcaagc) with identical cycling. The amplified products were cloned, sequenced, and identified by BLAST searches.

Reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction

Reverse transcriptase–PCR (RT-PCR) was performed with bone marrow RNA using paired PCR primers including AML1-3 (5′-gaaccaggttgcaag), AML1-6 (5′-ggggagtaggtgaaggcg), FOG2-15 (5′-gagacagacgactgggatggacc), and FOG2-12 (5′-cctctgacaccggagc). Cycling was as follows: 95°C for 1 minute (1 time); 95°C for 30 seconds, 45°C for 30 seconds, 68°C for 1 minute (35 times); 68°C for 1 minute (1 time).

Construction of AML1-FOG2 fusion

The AML1-FOG2 fusion was generated by overlap PCR using the following primers: AML1B-S (5′-gaggatccgcgatggcttcagacagcatatt), AML1-AS-OVLP (5′-tagttgtacaccaaagctgacccccctgcatctgactctgaggctgagg), FOG2-S-OVLP (5′-cctcagcctcagagtcagatgcaggggggtcagctttggtgtacaacta), and FOG2-AS-NT (5′-gaggatcctttgacatgttctgctgcatgtgatga) primers. The overlap product was ligated into the BamHI site of pCDNA3.1/V5-HisB (Invitrogen) and sequenced.

Reporter assay

One million 293 cells were transfected with calcium phosphate as described11,12 using combinations of plasmids AML1B, CBFβ, GATA1, AML1-FOG2, pcDNA3.1/V5-HisB, rous sarcoma virus (RSV)-LacZ, macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor promoter luciferase (MCSFR-Luc) reporter, and erythropoietin receptor promoter luciferase (EPOR-Luc) reporter. Relative luciferase activity represents the quotient of luciferase and β-galactosidase activities.

Immunoprecipitation

After transfection of 7 million 293 cells with either AML1-FOG2 or pcDNA3.1/V5-HisB, immunoprecipitation was performed with anti–V5 antibody (Invitrogen). Immunoblotting was performed with rabbit anti-CtBP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; sc-11 390) or goat anti-AML1 (Santa Cruz; sc-8563). Conversely, immunoprecipitation was performed with anti-CtBP followed by blotting with anti-V5.

Results and discussion

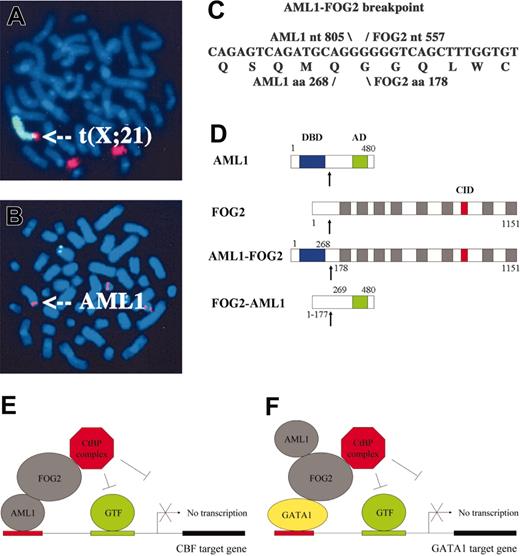

A 78-year-old male developed pancytopenia. Bone marrow evaluation revealed 5% blasts with erythroid and megakaryocytic dysplasia. He was diagnosed with myelodysplasia (French-American-British subtype refractory anemia with excess blasts), which did not respond to erythropoietin therapy. At the time of his death, he had progressive anemia and thrombocytopenia but no evidence of leukemia in his peripheral blood. Karyotype was 46, Y, t(X; 21)(p22.3;q22) which was confirmed using FISH with paints for the X chromosome and chromosome 21 (Figure 1A). Since AML1 resides at 21q22, we hypothesized that the t(X;21) involved translocation of AML1 to the X chromosome. FISH detected AML1 sequences not only as expected on both copies of chromosome 21 but also aberrantly on the X chromosome (Figure 1B).

Since there were no known AML1 translocations to the X chromosome, we initially hypothesized that the t(X;21) fused AML1 to a novel partner gene on the X chromosome. Surprisingly, 3′-RACE identified this gene as Friend of GATA-2 (FOG2/ZFPM2), which encodes a corepressor for the GATA transcription factors and normally resides on chromosome 8. Therefore, we performed FISH with a BAC probe against the 3′ end of FOG2 and independently confirmed translocation of the 3′ end of FOG2 to the X chromosome (data not shown). Thus, the t(X;21) represents a complex translocation involving not only Xp22 and 21q22 (AML1) but also 8q23 (FOG2).

Signficantly, there are at least 20 reported cases of either myelodysplasia or acute myeloid leukemia with chromosomal aberrations involving 8q23 (http://cgap.nci.nih.gov/Chromosomes/Mitelman). These cases include a disproportionate number of erythroleukemias and megakaryoblastic leukemias as might be predicted from the important role of GATA developmental programs in erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation. A search of the Southwest Oncology Group database identified 2 additional cases of acute myeloid leukemia involving 8q23. Collectively, these results raise the intriguing possibility that genetic events targeting FOG2 may occur more frequently in myeloid malignancies than previously recognized.

The t(X;21) fuses AML1 to FOG2. (A) FISH with paints for chromosomes X (green) and 21 (red) confirms t(X;21). (B) FISH with the AML1 probe (red) hybridizes not only to both copies of chromosome 21 but also aberrantly to a third chromosome (indicated by arrow). (C) AML1-FOG2 fuses AML1 nt 805 to FOG2 nt 557 and encodes a chimeric protein composed of AML1 aa 1-268 fused to FOG2 aa 178-1151. (D) Structures for the chimeric fusion proteins are shown relative to those for AML1 and FOG2. AML1-FOG2 retains the DNA-binding domain (DBD; blue boxes) of AML1 plus the 8 zinc finger domains (▦) and CtBP interaction domain (CID; red boxes) of FOG2, whereas FOG2-AML1 retains the activation domain (AD; green boxes) of AML1. The fusion breakpoints are indicated by arrows. (E) Model for transcriptional repression of CBF target genes in which AML1-FOG2 binds the promoter via the DBD from AML1 but aberrantly recruits the CtBP corepressor complex (GTF, general transcription factors). (F) Model for transcriptional repression of GATA1 target genes in which AML1-FOG2 binds the promoter via interaction with GATA1 but aberrantly recruits the CtBP corepressor complex.

The t(X;21) fuses AML1 to FOG2. (A) FISH with paints for chromosomes X (green) and 21 (red) confirms t(X;21). (B) FISH with the AML1 probe (red) hybridizes not only to both copies of chromosome 21 but also aberrantly to a third chromosome (indicated by arrow). (C) AML1-FOG2 fuses AML1 nt 805 to FOG2 nt 557 and encodes a chimeric protein composed of AML1 aa 1-268 fused to FOG2 aa 178-1151. (D) Structures for the chimeric fusion proteins are shown relative to those for AML1 and FOG2. AML1-FOG2 retains the DNA-binding domain (DBD; blue boxes) of AML1 plus the 8 zinc finger domains (▦) and CtBP interaction domain (CID; red boxes) of FOG2, whereas FOG2-AML1 retains the activation domain (AD; green boxes) of AML1. The fusion breakpoints are indicated by arrows. (E) Model for transcriptional repression of CBF target genes in which AML1-FOG2 binds the promoter via the DBD from AML1 but aberrantly recruits the CtBP corepressor complex (GTF, general transcription factors). (F) Model for transcriptional repression of GATA1 target genes in which AML1-FOG2 binds the promoter via interaction with GATA1 but aberrantly recruits the CtBP corepressor complex.

The AML1-FOG2 breakpoint fuses nucleotide 805 from exon 6 of AML1 [U19 601] to nucleotide 557 from exon 6 of FOG2 [AF119 334] (Figure 1C). The protein consists of 1242 amino acids and fuses aa 1-268 of AML1 to aa 178-1151 of FOG2 (Figure 1D). Thus, AML1-FOG2 retains the DNA-binding domain of AML1 and most of FOG2 including its 8 zinc fingers and the interaction domain13,14 that recruits the corepressor C-terminal binding protein (CtBP). Whereas FOG2 normally plays an important role in sex determination15 and cardiac development,16,17 the t(X;21) represents the first demonstration of a role for the FOG family in neoplasia.

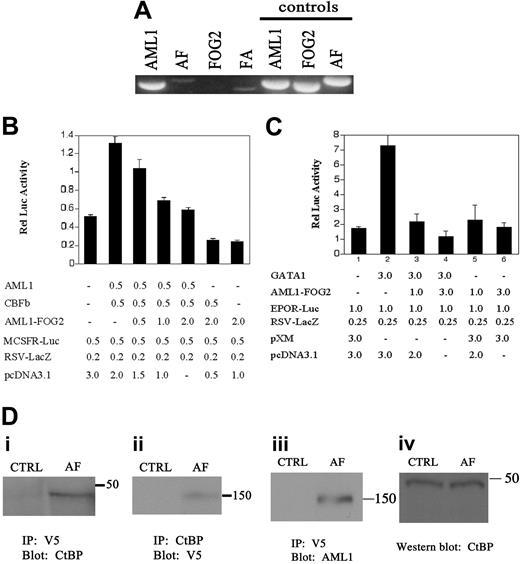

RT-PCR detected expression of not only AML1 but also the reciprocal gene fusions AML1-FOG2 and FOG2-AML1 (Figure 2A). Expression of FOG2 was not detectable despite structural evidence from FISH that the untranslocated allele was not deleted. The absence of FOG2 expression may reflect its normal tissue-specific expression pattern, alteration in its expression pattern induced by the fusions, or loss of heterozygosity for FOG2 as a result of the translocation.

The structural features of AML1-FOG2 indicate that the fusion protein may disrupt both the CBF and GATA developmental programs (Figure 1D). Because AML1-FOG2 retains the DNA-binding domain (DBD) from AML1 and the CtBP interaction domain (CID) from FOG2, we hypothesized that it binds the promoters of CBF target genes, such as macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor (MCSFR), and blocks their expression through aberrant recruitment of CtBP (Figure 1E). Cotransfection of CBF with increasing amounts of AML1-FOG2 in the presence of the MCSFR-Luc reporter demonstrated that AML1-FOG2 represses CBF-mediated transcriptional activity (Figure 2B). Since AML1-FOG2 retains the zinc fingers that interact with the GATA transcription factors and the CtBP interaction domain from FOG2, we hypothesized that it also binds GATA proteins at the promoters of their target genes, such as erthyropoietin receptor (EPOR), and blocks their expression through aberrant recruitment of CtBP (Figure 1F). Predictably, cotransfection of GATA1 with increasing amounts of AML1-FOG2 in the presence of the EPOR-Luc reporter demonstrated that AML1-FOG2 also repressed GATA1-mediated transcriptional activity (Figure 2C). Importantly, future studies will need to investigate if AML1-FOG2 interacts directly with GATA1 and whether expression of AML1-FOG2 produces a hematopoietic phenotype. Finally, it is notable that the reciprocal fusion FOG2-AML1, which retains the activation domain but not the DBD of AML1 (Figure 1D), may also reduce the transcriptional activity of wild-type AML1 by sequestering specific coactivators such as camp response element binding protein (CREB).

AML1-FOG2 functions as a transcriptional repressor and recruits CtBP. (A) The reciprocal transcripts AML1-FOG2 (AF) and FOG2-AML1 (FA) can be detected in the bone marrow by RT-PCR. The AML1 transcript is also detected, whereas the FOG2 transcript is not detected. Control PCR reactions were performed in parallel using identical primer pairs and 50 ng plasmid DNA as template. (B) AML1-FOG2 represses the transcriptional activity of CBF. For each transfection, the graph depicts the mean and standard deviation for 6 independent replicates. The amount of each plasmid transfected is indicated in micrograms. CBFb refers to CBFβ. (C) AML1-FOG2 represses the transcriptional activity of GATA1. For each transfection, the graph depicts the mean and standard deviation for 3 independent replicates. The amount of each plasmid transfected is indicated in micrograms. (D) AML1-FOG2 and CtBP associate in a protein complex. 293 cells were transfected with either pCDNA3.1/V5-HisB (CTRL) or V5-epitope tagged AML1-FOG2 (AF). Molecular weights of markers are indicated in kilodaltons. (i) Immunoprecipitation of AML1-FOG2 with anti–V5 antibody specifically recovers CtBP. (ii) Immunoprecipitation of CtBP with anti–CtBP antibody specifically recovers AML1-FOG2. (iii) Control immunoprecipitation with anti-V5 shows that AML1-FOG2 is expressed after transfection and can be detected with anti–AML1 antibody. (iv) Control blot with anti–CtBP antibody shows equal amounts of endogenous CtBP in the protein lysates used for immunoprecipitation experiments.

AML1-FOG2 functions as a transcriptional repressor and recruits CtBP. (A) The reciprocal transcripts AML1-FOG2 (AF) and FOG2-AML1 (FA) can be detected in the bone marrow by RT-PCR. The AML1 transcript is also detected, whereas the FOG2 transcript is not detected. Control PCR reactions were performed in parallel using identical primer pairs and 50 ng plasmid DNA as template. (B) AML1-FOG2 represses the transcriptional activity of CBF. For each transfection, the graph depicts the mean and standard deviation for 6 independent replicates. The amount of each plasmid transfected is indicated in micrograms. CBFb refers to CBFβ. (C) AML1-FOG2 represses the transcriptional activity of GATA1. For each transfection, the graph depicts the mean and standard deviation for 3 independent replicates. The amount of each plasmid transfected is indicated in micrograms. (D) AML1-FOG2 and CtBP associate in a protein complex. 293 cells were transfected with either pCDNA3.1/V5-HisB (CTRL) or V5-epitope tagged AML1-FOG2 (AF). Molecular weights of markers are indicated in kilodaltons. (i) Immunoprecipitation of AML1-FOG2 with anti–V5 antibody specifically recovers CtBP. (ii) Immunoprecipitation of CtBP with anti–CtBP antibody specifically recovers AML1-FOG2. (iii) Control immunoprecipitation with anti-V5 shows that AML1-FOG2 is expressed after transfection and can be detected with anti–AML1 antibody. (iv) Control blot with anti–CtBP antibody shows equal amounts of endogenous CtBP in the protein lysates used for immunoprecipitation experiments.

Since AML1-FOG2 contains the peptide motif that recruits the corepressor CtBP, we hypothesized that AML1-FOG2 and CtBP interact in a protein complex. Immunoprecipitation experiments in 293 cells transfected with either vector alone or AML1-FOG2 demonstrated that AML1-FOG2 and CtBP specifically associate in vivo (Figure 2D). Control experiments confirmed expression of AML1-FOG2 after transfection as well as equivalent amounts of endogenous CtBP in the protein lysates used for immunoprecipitation (Figure 2D). The CtBP repressor complex includes histone deacetylases and methyltransferases as well as Polycomb proteins.18 Thus, AML1-FOG2 may repress CBF hematopoietic developmental pathways by aberrantly recruiting the CtBP complex to CBF target genes. Such a mechanism is functionally reminiscent of that described for AML1-MDS1-EVI1 in myelodysplasia19 and may represent a central event in the pathogenesis of myelodysplasia.

Since AML1-FOG2 retains the zinc fingers of FOG2 that interact with GATA proteins,14 it may also disrupt GATA-dependent hematopoietic programs in vivo. Interestingly, ectopic expression of FOG2 in Xenopus embryos produces severe anemia if the CtBP interaction motif is retained20 and raises the possibility that AML1-FOG2 represents ectopic expression of FOG2 in human hematopoietic cells. Moreover, the clinical phenotype associated with AML1-FOG2 demonstrates remarkable similarity to X-linked dyserythropoietic anemia and thrombocytopenia, which is due to a mutation in GATA1.21 Thus, it will be important to determine if AML1-FOG2 interacts with GATA proteins in hematopoietic cells, whether CtBP plays a more central role in the pathogenesis of myelodysplasia, and if genetic alterations in the CBF and GATA developmental pathways cooperate to induce hematologic malignancies.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, February 10, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2762.

Supported by American Cancer Society grant IRG-84-002-17 (E.M.C.) and by a grant from the Clarian Values Fund for Research (E.M.C.).

Presented in part at the 44th and 46th Annual Meetings of the American Society of Hematology, December 2002 and December 2004.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal