Comment on Mims et al, page 1337

A new human genetic model of hypochromic microcytic anemia is due to DMT1 mutations. At variance with rodent models, the first identified patient is also iron loaded.

Mims and colleagues have identified the first human example of the iron transporter divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) mutation. DMT1 is a transmembrane protein involved in dietary nonheme iron uptake at the brush border of duodenal enterocytes and also plays a crucial role in iron utilization at the endosomal membrane of the erythroid precursors. DMT1 gene was cloned and its function clarified thanks to the study of rodents (mk mouse1 and Belgrade rat2 ) affected by severe iron-deficient anemia. Both animal strains have greatly reduced intestinal iron absorption and impaired iron use by the erythron. Curiously, they harbor the same missense (Gly185Arg) DMT1 homozygous mutation.FIG1

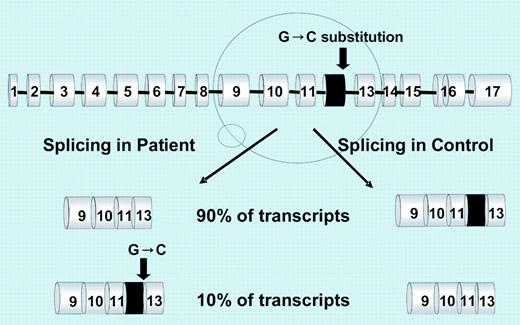

Schematic representation of the mutation effect. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 1337.

Schematic representation of the mutation effect. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 1337.

The 20-year-old female described by Mims et al, product of a consanguineous union, had severe congenital hypochromic microcytic anemia due to defective iron transport and utilization in erythroid precursors. However, high serum iron, normal total iron-binding capacity, and high serum ferritin levels were inconsistent with iron deficiency. In addition, she had severe hepatic iron overload, minimally accounted for by occasional blood transfusions.

Sequencing of DMT1 RNA revealed a homozygous G>C mutation of the last nucleotide of exon 12. The mutation introduces a harmless amino acid change (Glu399Asp) but causes the skipping of exon 12, which results in a shorter RNA. Skipping of exon 12, expected to remove transmembrane domain 8, occurs physiologically at a minimal rate in blood cells but prevails in the proband reticulocytes and duodenum (see figure). It is unknown whether the RNA variant results in a shorter protein (no abnormal protein was demonstrated in duodenum). How this abnormality causes the patient's phenotype remains to be fully understood, the more likely explanation being a quantitative DMT1 protein reduction.

This important finding strengthens not only the homologies but also the differences between rodent and human iron disorders and has biologic and clinical implications. In animal models, the reduction of DMT1 causes pure iron deficiency1,2 ; the patient has a more complex phenotype with biochemical and histologic features of iron overload. Hepatic iron overload implies increased duodenal absorption that can hardly be ascribed to a defective DMT1. One possible way to explain this puzzling feature and the discrepancy with the rodent model is that the human defect affects prevalently erythroid rather than intestinal DMT1 function. Indeed, the mutation type (missense in rodents and splicing in humans) is different. Alternatively, intestinal iron uptake in humans could occur through mechanisms that bypass DMT1 function (eg, through heme hyperabsorption), a pathway negligible in rodents. Another possibility, compatible with the patient's low urinary hepcidin, is increased iron export at the basolateral membrane. Irrespective of the mechanism, the case described indicates that human DMT1 has a prevalent role in erythroid cells compared with the duodenum.

Common causes of severe microcytic anemia are iron deficiency, thalassemias, and sideroblastic anemias. Screening DMT1 for mutations is a new option for the rare cases of familial or atypical microcytosis, which are at the cutting edge between iron deficiency and overload. ▪

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal